Abstract

Objectives

Three-dimensional (3D)/4-dimensional (4D) sonographic measurement of blood volume flow in transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) revision with the intention of objective assessment of shunt patency.

Methods

A total of 17 patients were recruited (12 males, 5 females, mean age 55 years, range 30–69 years). A GE LOGIQ 9 ultrasound system (4D3CL; 2.0–5.0 MHz) was used to acquire multi-volume 3D/4D color Doppler data sets to assess pre- and post-revision shunt volume flow. Volume flow was computed offline based on the principle of surface integration of Doppler-measured velocity vectors in a lateral-elevational c-surface positioned at the color flow focal depth (range 8.0–11.5 cm). Volume flow was compared to routine measurements of pre- and post-revision portosystemic pressure gradient. Pre-revision volume flow was compared with outcome to determine if a flow threshold for revision could be defined.

Results

Linear regression of data from revised TIPS cases showed an inverse correlation between mean-normalized change in pre- and post-revision shunt volume flow and mean-normalized change in pre- and post-revision portosystemic pressure gradient (r2 = 0.51, P-value = 0.020). Increased shunt blood flow corresponded with decreased pressure gradient. Comparison of pre-revision flows showed a preliminary threshold develop at 1534 mL/min, below which a shunt revision may be recommended (P-value = 0.21, AROC = 0.78).

Conclusions

Shunt volume flow measurement with 3D/4D Doppler sonography provides a potential alternative to standard pulsed-wave Doppler metrics as an indicator of shunt function and predictor of revision.

Keywords: color flow, Doppler sonography, portal hypertension, power Doppler, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) revision, volume flow

Introduction

Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) are employed in the management of portal hypertension and related portal-hypertensive complications such as variceal hemorrhage and ascites (1–6). Thrombosis or stenosis of the shunt is a principal concern as demonstrated by primary shunt patency rates: 25–66%, 5–42%, 21%, 13%, and 13% at years 1–5, respectively (3, 4, 7–13). Primary shunt patency rates have been updated by the introduction of covered stents which show lower rates of failure than uncovered stents. A recent study by Bureau et al. (14) compared outcomes in 39 patients with covered stents and 41 patients with uncovered stents. Covered-stent shunt dysfunction was shown in 13% of patients based on the criteria of >50% stenosis or a portosystemic pressure gradient (PSPG) >12 mmHg after a median follow-up of 300 days. Other investigators have shown covered stent dysfunction rates between 8–20% at 1 year (15–19). However, approximately 20% of TIPS procedures in the United States still use uncovered stents (20).

Interventional revision prolongs patency, and if performed before complete occlusion, yields increased primary-assisted patency rates: 80–85%, 61–79%, 46–87%, 42%, and 36% at years 1–5, respectively (4, 7–11, 13). Therefore, shunt dysfunction must be identified promptly and managed appropriately in order to define a therapeutic window for revision.

TIPS screening identifies cases that require revision, but current sonographic assessment techniques have variable sensitivity and specificity, and venography, the gold standard for detecting shunt dysfunction, is invasive and unsuitable for routine use (4, 6). Doppler ultrasound is the primary imaging modality used for TIPS patency screening (4, 6). Although several flow velocity criteria for defining TIPS failure have been proposed in the literature, each has proponents and detractors and a nonuniform association exists between flow velocity and shunt patency (4, 6, 21–27). Literature has also demonstrated poor correlation (r = −0.11) between flow velocity and PSPG (28). Variability in the flow velocity estimate is motivated by several objective and subjective factors: resistance of the overall flow path, Doppler angle, cylindrically asymmetric flow profile, internal aliasing, and shunt morphology such as overlapping stents or curves in the shunt. Individually or collectively, these factors can yield velocity fluctuation along the length of the shunt.

Volume flow is an alternative metric to flow velocity that may be used to assess shunt patency (29–31). In TIPS, since there is only one inflow and one outflow, volume flow is conserved and thus equivalent everywhere along the path of the shunt. Therefore, volume flow provides a potentially robust metric for evaluating shunt patency.

The proposed 3-dimensional (3D)/4-dimensional (4D) volume flow measurement technique—based on surface integration of Doppler-measured velocity vectors (SIVV)—is non-invasive, objective, and independent of all traditional pulsed-wave Doppler assumptions (32–37). Measurement of TIPS volume flow is demonstrated in patients undergoing revision and compared to standard measurements of revision PSPG. Volume flow measurements are also evaluated on the basis of pre-revision shunt flow and outcome to determine if a flow threshold for revision could be defined. The hypothesis of this study is that the proposed 3D/4D sonographic volume flow (3D/4D SVF) measurement technique provides straightforward, objective, and reliable assessment of shunt flow as a means for determining patency and defining a therapeutic strategy for revision.

Materials and Methods

A total of 17 patients admitted for TIPS revision were consecutively enrolled from the University of Michigan Medical Center’s interventional radiology service in this prospective study. This patient population was selected because pre- and post-revision PSPG measurements would be available as a gold standard for comparison with the volume flow estimates. Patient demographics and clinical characteristics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2. Table 2 shows a total prospective patient count of 19 because patient 3 was scanned three times on separate hospital visits (3A, 3B, 3C). Patients included in the study were referred to interventional radiology with clinical signs of shunt dysfunction (re-accumulation of ascites, hepatic hydrothorax) or ultrasound demonstrating a temporal change in shunt velocities or flow patterns. Each patient provided fully informed written consent to an IRB-approved protocol involving transcutaneous measurement of blood volume flow using ultrasound. Patients unwilling to sign consent were excluded from the study.

Table 1.

Patient Demographics

| Gender [male, female] | 12, 5 |

| Age (year) [mean, range] | 55, 30–69 |

| Etiology of cirrhosis | |

| Alcohol | 4 |

| Hepatitis C | 3 |

| Sclerosing cholangitis | 1 |

| NASH/cryptogenic | 6 |

| Budd-Chiari | 1 |

| Mesenteric thrombosis | 1 |

| Congenital hepatic fibrosis | 1 |

| Indication | |

| Varices | 6 |

| Ascites | 10 |

| Both | 1 |

Table 2.

Patient Clinical Characteristics

| Months after TIPS creation | Months after most recent revision | Stent type | Clinical indication for revision | Morphological indication for revision | Abnormal ultrasound1 | Revision type | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pt 1* | 68 | 62 | VSG | Asymptomatic | None | Yes | None |

| Pt 2* | 1 | VSG | Refractory ascites | None | Yes | None | |

| Pt 3 (3A) | 17 | 6 | VSG | Refractory ascites | Stenosis | Yes | Balloon angioplasty |

| Pt 4 | 143 | BMS | Asymptomatic | Stenosis | Yes | Balloon angioplasty | |

| Pt 5 | 60 | VSG | Refractory ascites | Occlusion | Yes | Balloon angioplasty | |

| Pt 6* | 27 | VSG | Refractory ascites | None | Yes | None | |

| Pt 7* | 1 | BMS | Refractory ascites | Occlusion | Yes | Stent graft implantation | |

| Pt 8* | 20 | 6 | VSG | Refractory ascites | Occlusion | Yes | Bare stent implantation |

| Pt 9 | 24 | VSG | Refractory ascites | Stenosis | No | Balloon angioplasty | |

| Pt 10 | 24 | VSG | Refractory ascites | Stenosis | Yes | Bare stent implantation | |

| Pt 11 | 112 | 104 | BMS | Refractory ascites | Stenosis | Yes | Balloon angioplasty |

| Pt 12 | 12 | VSG | Refractory ascites | Stenosis | Yes | Bare stent implantation | |

| Pt 13 | 126 | 81 | VSG | Asymptomatic | None | Yes | None |

| Pt 14 | 42 | 14 | VSG | Refractory ascites | Stenosis | Yes | Balloon angioplasty |

| Pt 15 (3B) | 23 | 5 | VSG | Refractory ascites | Stenosis | Yes | Balloon angioplasty |

| Pt 16 | 166 | VSG | Asymptomatic | None | Yes | Balloon angioplasty | |

| Pt 17 | 12 | VSG | Refractory ascites | None | No | Balloon angioplasty | |

| Pt 18 | 12 | VSG | Asymptomatic | None | Yes | None | |

| Pt 19 (3C) | 28 | 5 | VSG | Refractory ascites | Stenosis | Yes | Bare stent |

Pt: Patient; VSG: Viatorr stent-graft; BMS: Bare metal stent; 3A, 3B, 3C: Multiple studies in Pt 3

Omitted for reasons as described in the text

Abnormal ultrasound consists of one or more of the following criteria: (1) change in baseline velocities, (2) reversal of flow in left or right portal vein away from TIPS, or (3) absence of flow in TIPS.

From the 17-patient population, a total of 20 TIPS cases were obtained because patient 5 had two TIPS and patient 3 was scanned three times on separate hospital visits. The 20 cases can be categorized as follows: 12 TIPS revised, 3 TIPS not revised, and 5 TIPS cases omitted. Cases were omitted for one of the following reasons, neither of which was due to the SIVV volume flow technique, but to unrelated factors: (1) data acquisition error, (2) inadequate color flow image quality, (3) high BMI patient, i.e., poor acoustic access, and (4) fully thrombosed shunt, i.e., lack of pre-revision pressure gradient. These cases are marked with an asterisk in Table 2. In addition, two revised cases (patients 5 and 11) were excluded as will be described in the Results.

Shunt volume flow was assessed twice for each patient with one flow measurement immediately prior to revision (<2 hours) and one flow measurement immediately subsequent to revision (<2 hours). All patients were NPO (nil per os or nothing by mouth) for at least 6 hours prior to pre-revision volume flow measurement and maintained as NPO for the post-revision scan.

TIPS revision followed the standard interventional radiology protocol at the University of Michigan Medical Center (PMN; 11 years of experience). Decision for angioplasty was based on venographically visible stenosis. Stents were dilated using a 4-cm long balloon equal in diameter to the original stent. Viatorr stents were dilated to 10 mm. Angioplasty was followed by stent revision if venographic success was not achieved. A peak systolic gradient between the right portal vein and right atrium >12 mmHg defined TIPS dysfunction. Venography was performed in all patients to document stent luminal caliber, flow reversal in portal circulation, and antegrade flow in hepatic portal venous branches. Pressure measurements were made under quiet tidal respiration and averaged over 20 seconds.

A GE LOGIQ 9 ultrasound system (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA) equipped with a 2.0–5.0 MHz probe (4D3CL) was used to acquire multi-volume 4D (near real-time 3D) color Doppler data sets. Each multi-volume data set consisted of 30 image volumes acquired sequentially at a rate of one volume every 10 seconds. This corresponds to an acquisition rate of 0.1 Hz, although the acquisitions were not continuous. Patients held their breath during a volume acquisition and breathed between acquisitions. There was also a time delay for the 3D reconstruction between acquisitions. Since TIPS flow can be respiratory-phase dependent (38), subjects were instructed to simply stop breathing with no bias towards inspiration or expiration. Multi-volume data sets were processed offline by exporting GE LOGIQ 9 4D duplex mode raw DICOM data (Medical Imaging & Technology Alliance, Arlington, VA, USA) and the associated scanner acquisition settings for prospective analysis.

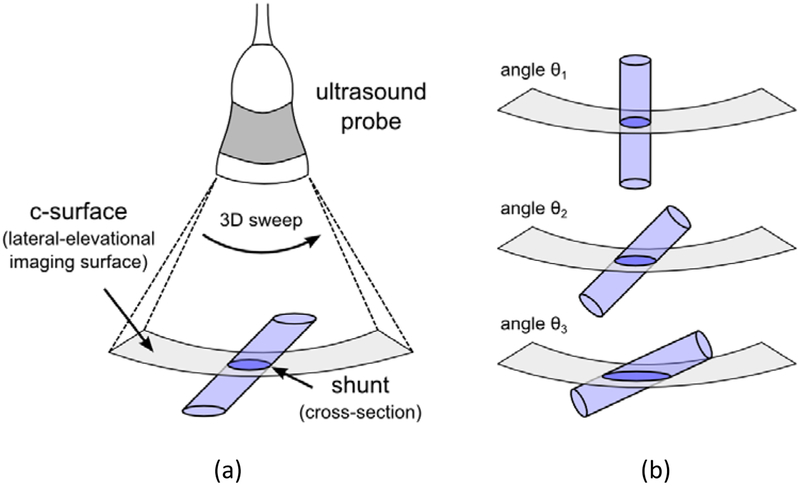

Figure 1 illustrates the imaging geometry required with the proposed volume flow technique. The position and tilt angle of the probe must be adjusted to visualize the shunt cross section in the lateral-elevational imaging surface. Although the shunt is required to intersect the c-surface in cross section (Figure 1a), the volume flow method is independent of the angle at which the shunt intersects the c-surface. For example, the shunt cross section can vary from circular to ellipsoidal (Figure 1b) and each geometry will yield an identical volume flow estimate. The c-surface was typically positioned near mid-stent and as close as possible to the color flow focus which ranged in depth from 8.0–11.5 cm (one case: 14.5 cm) depending on the position of the shunt, patient BMI, and the presence of overlying ascites. For the 8.0–11.5 cm depth range, the c-surface consisted of a lateral pixel size range of 1.2–1.5 mm and an elevational pixel size range of 1.5–2.0 mm.

Figure 1:

(a) Imaging geometry required with proposed volume flow measurement technique. The probe is oriented such that the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) intersects the c-surface (lateral-elevational surface) in cross section. (b) Angle of c-surface intersection is an independent variable. The TIPS can intersect the c-surface at angles which yield circular (θ1) to ellipsoidal (θ2, θ3) geometries and all cases would yield an identical volume flow estimate.

Volume flow for each multi-volume data set was computed offline (SZP) using custom algorithms written in MATLAB (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA, USA), which implemented the principle of surface integration of Doppler-measured velocity vectors (SIVV) (32, 34). The computation c-surface was defined at, or near, the color flow focus of the acquired 3D volume. Power Doppler data were used as a correction factor to compensate for partial volume effects by weighting flow estimates in reference to pixels containing 100% blood (33, 35, 36). Principles of the volume flow computation method are described later in this section.

For each 30-volume data set, volume flow was computed on a volume-by-volume basis to yield 30 individual estimates that were subsequently averaged to produce the overall flow in the shunt. Volume-by-volume flow computation is advantageous because it allows for shunt motion (respiration, bulk motion, probe movement) within the scanning volume of interest between acquisitions. In some data sets, however, a few individual volumes were discarded due to movement during an acquisition.

Two segmentation methods were employed to exclude unrelated vasculature and local color flow artifacts from the c-surface. First, directional criteria were used to automatically differentiate shunt flow from any adjacent arterial flow. Second, manual segmentation (SZP) placed a broad outline around the shunt and excluded extraneous vessels and artifacts in the volume of interest.

Pre- and post-revision shunt volume flow measurements made by ultrasound were compared to routine measurements of pre- and post-revision PSPG measured via catheter using an electronic manometer. The volume flow metric was defined as mean-normalized change in pre- and post-revision shunt volume flow (ΔQ/Qavg) and the PSPG metric was defined as mean-normalized change in pre- and post-revision PSPG (ΔP/Pavg). Data were also evaluated on the basis of pre-revision shunt volume flow and outcome to determine if a flow threshold for revision could be defined. Clinical outcomes and PSPG measurements were abstracted from the medical records of the recruited patients.

Statistical Methods

Linear regression analysis was performed between the volume flow and PSPG metrics and plotted with a 95% confidence interval. The ΔQ/Qavg volume flow metric was reported as mean and standard deviation, where the standard deviation was computed using the standard rules of error propagation for an up to 30-volume data set. Groups were compared using the t test for independent samples and reported with a two-tailed P value. Individual groups were reported with a mean and standard error. All statistical analyses were performed with software (GraphPad, Prism 5, La Jolla, CA). P < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

Power-Weighted Surface Integration of Doppler-Measured Velocity Vectors (SIVV)

Surface integration of Doppler-measured velocity vectors is based on Gauss’ divergence theorem. Volume flow, Q, can be defined as the total flux through a surface, S, that completely transects a vessel:

| (1) |

where v is the Doppler-measured velocity vector and A is the surface area element. The scanning geometry illustrated in Figure 1 ensures that normality is maintained between the local velocity vector and the local surface area element; therefore, the dot product in equation (1) simplifies to a multiplication. With this simplification and in the discrete case, mean volume flow through a c-surface can be re-defined as:

| (2) |

where vi is the mean local Doppler-measured velocity vector for a single pixel i, Ai is the local surface area of the corresponding pixel i, and i is taken over all pixels in the c-surface. The velocity vector and surface area element must be normal (i.e., perpendicular) for the application of equation (2).

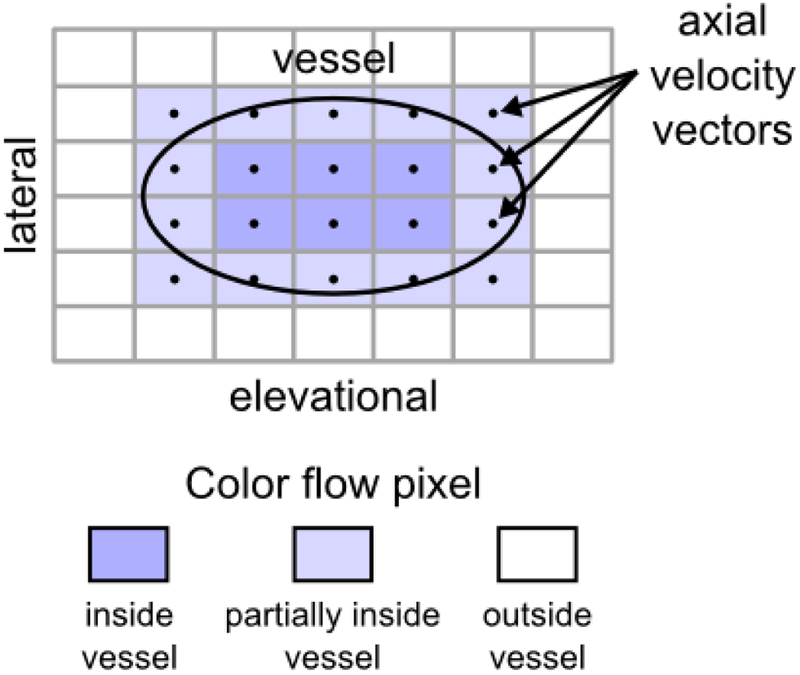

Figure 2 illustrates the principle of power-weighted SIVV for a single vessel with an ellipsoidal cross section in the c-surface. For color flow pixels that fully intersect the vessel (six dark blue pixels in Figure 2), volumetric flow through the pixel c-surface can be computed using equation (2). However, a subset of color flow pixels in Figure 2 only partially intersect the vessel (14 light blue pixels in Figure 2) and thus contribute only partially to the flow estimate. The extent of partial contribution is determined by the power Doppler signal, which is assumed directly proportional to the number of scattering red blood cells (33). A weighting factor, w, computed in reference to the power in pixels containing 100% blood reflects the fraction of blood intersected by the pixel and is applied to the volume flow estimate as follows:

| (3) |

where 0 ≤ wi ≤ 1 and i is taken over all pixels in the c-surface. For example, wi = 0.5 indicates a pixel area which contains, or intersects, only 50% blood. Power weighting automatically identifies the vessel boundary because the weighting factor is zero outside the vessel. Only a broad vessel outline is required to exclude extraneous flow and artifacts.

Figure 2:

Power-weighted surface integration of Doppler-measured velocity vectors (SIVV) illustrated on a vessel with an ellipsoidal cross section (black outline) in the lateral-elevational imaging surface (c-surface). Each color flow pixel that intersects the vessel possesses a Doppler-measured axial velocity vector that is normal to the area element. Axial velocity vectors point out of the page. Color flow pixels positioned inside the vessel correspond to 100% blood, those outside the vessel correspond to 0% blood, and those partially inside the vessel correspond to a value between 0% and 100% blood. Integration of flow over the c-surface yields volume flow through the shunt.

The following describes the steps to determine the weighting factor. A histogram is generated using Doppler power values corresponding to each velocity measurement on the c-surface. The Doppler power value that corresponds to the peak in the histogram is selected automatically and defined as pmax. A power threshold, pthres, is chosen as 90% of pmax and identifies the minimum power value of those pixels positioned fully inside the vessel. This power threshold represents the minimum power value of 100% blood. Color flow pixels associated with Doppler power values greater than or equal to pthres are set to possess a weighting factor w = 1. The remaining Doppler power values, all of which are greater than or equal to zero but less than pthres are linearly scaled to possess a weighting factor between 0 ≤ w < 1. The weighting factor is assigned irrespective of color pixel spatial position. Evaluation of equation (3) yields the total flow through the shunt while correcting for the partial volume effect.

Results

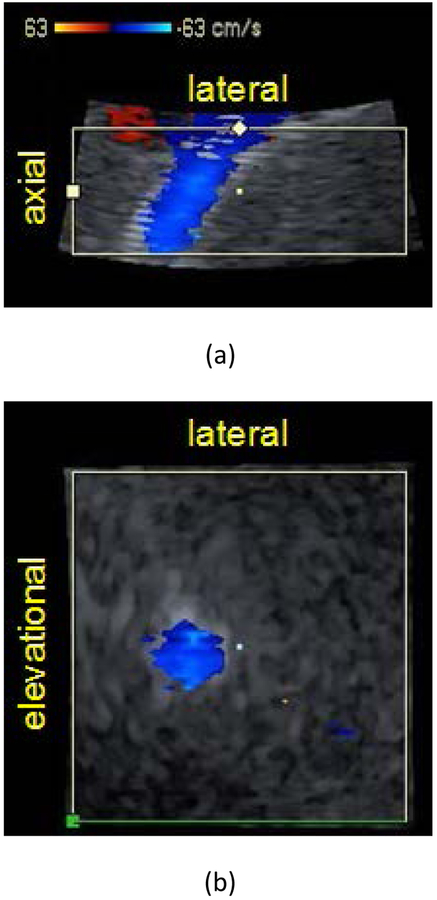

Figure 3 shows representative axial-lateral (Figure 3a) and elevational-lateral (Figure 3b) color flow images of a single volumetric TIPS scan for patient 4 post revision. Shunt volume flow can be assessed using the proposed method as long as the elevational-lateral surface, or constant depth c-surface, can be positioned to fully intersect the shunt in cross section as shown in Figure 3b. This cross sectional orientation was achieved for each recruited patient and demonstrates the broad applicability of the method.

Figure 3:

Color flow images of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) in (a) axial-lateral and (b) elevational-lateral (c-surface) views for patient 4 post revision. Panels (a) and (b) coincide at the center point marked in each view. Color flow focus depth is 11.25 cm and is positioned at the axial center of (a). The elevational-lateral surface intersects the shunt at a depth of 11.25 cm. B-Mode image striations in (a) represent stent mesh boundary. Color bar indicates velocity in cm/s.

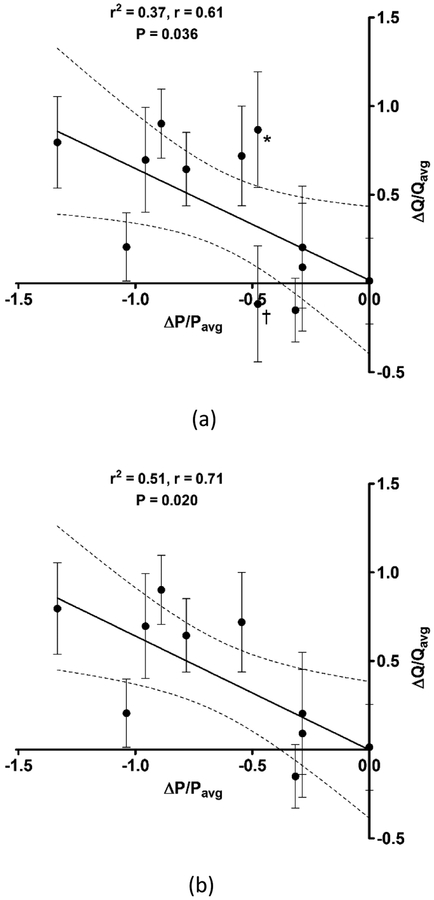

Figure 4 shows the relationship between the ΔQ/Qavg volume flow metric and the ΔP/Pavg PSPG metric. The 12 out of the 20 TIPS cases for which a revision was performed are included in the linear regression of Figure 4a, which demonstrates an inverse correlation between TIPS volume flow and PSPG. An increase in shunt volume flow corresponds with a decrease in PSPG.

Figure 4:

Relationship between mean-normalized change in pre- and post-revision shunt volume flow (ΔQ/Qavg) and mean-normalized change in pre- and post-revision portosystemic pressure gradient (ΔP/Pavg) for (a) all transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) cases for which a revision was performed and (b) excluding two revised TIPS cases (*,†) for reasons as described in the text. Solid line represents the linear regression and dashed lines represent 95% confidence intervals. Error bars indicate standard deviation in the flow metric for an up to 30-volume data set.

An updated linear regression is presented in Figure 4b, where two specific revised cases were excluded from the data set. Patient 5 (*) had two TIPS of which one shunt was revised and the other shunt was not revised. Following revision, increased flow was observed in both shunts and therefore the volume flow and PSPG metrics could not be reliably computed. Given that the two shunts are components in a complex parallel vascular flow circuit (39), the flow path through a two-TIPS morphology is not clearly understood. Patient 11 (†) exhibited an atypical breathing pattern that was required in order to observe flow within the shunt lumen. Given the described circumstances, these two cases can be justifiably excluded and the updated linear regression shows a stronger correlation between the volume flow and PSPG metrics.

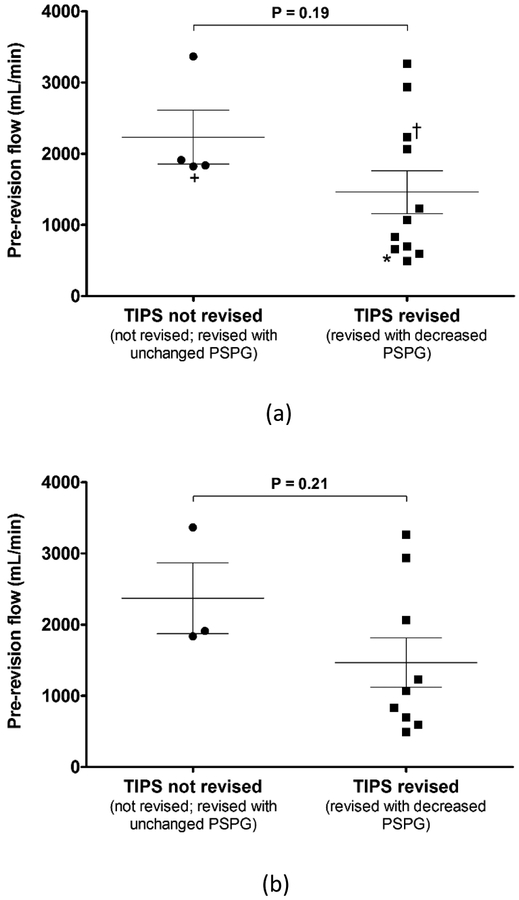

Figure 5 provides a pre-revision TIPS volume flow comparison between cases not revised or revised with an unchanged PSPG and cases revised with a decreased PSPG. All 15 TIPS cases (12 revised, 3 not revised) are included in the comparison of Figure 5a. An updated comparison is presented in Figure 5b, where the same two cases (patients 5 and 11), as described above, are excluded from the data set. Overall, three data points are excluded from Figure 5b because patient 5 had two TIPS and both the revised (*) and non-revised (+) pre-revision flow measurements are omitted.

Figure 5:

Pre-revision transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) volume flow comparison between cases not revised or revised with unchanged portosystemic pressure gradient (PSPG) and cases revised with decreased PSPG for (a) all TIPS cases and (b) excluding two TIPS cases, i.e., three data points (*,+,†), for reasons as described in the text. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean.

Comparison of pre-revision flows shows a developing threshold below which a TIPS revision may be recommended. A volume flow threshold of 1534 mL/min yields a sensitivity of 66.7% and a specificity of 100%. A less conservative volume flow threshold of 1873 mL/min yields a sensitivity of 66.7% and a specificity of 66.7%. The ability of shunt volume flow to discriminate between individuals requiring a revision and those not requiring a revision is 73% (AROC = 0.73) and 78% (AROC = 0.78), for Figures 5a and 5b, respectively.

Discussion

Doppler ultrasound has traditionally been the primary mode for TIPS evaluation and is generally accepted as an excellent method for detecting complete shunt occlusion (4, 21, 22, 24–26). However, a completely occluded shunt is typically more difficult to revise, so a failing TIPS must be identified promptly and revised before this time point. Current Doppler methods have demonstrated an opportunity for improvement.

Given the complexity in the parallel vascular flow circuit (39), shunt flow velocity depends on several factors in the overall circuit and one can conceive of situations where local blood flow velocities can increase, decrease, or remain unchanged in a failing TIPS. In the presence of a relative stenosis, shunt cross-sectional area will decrease. If the TIPS behaved identical to a blood vessel that supplies an organ which autoregulates, flow velocity at the stenosis would increase to maintain constant volume flow (this principle is used to estimate stenoses in carotid and renal Doppler examinations). However, TIPS does not autoregulate and is simply intended to function as a low resistance short circuit that diverts blood flow away from a cirrhotic liver or varices. Therefore, in TIPS, a stenosis produces an increase in local flow resistance and may cause diversion of blood flow to other parts of the vascular flow circuit. If the decrease in blood flow equally compensates for the decrease in cross-sectional area, local flow velocity will remain unchanged even though a TIPS stenosis exists. In addition, flow velocity can vary along the path of the shunt and even fluctuate with time (4, 40).

Variability in the flow velocity estimate is apparent in recent studies that have shown unreliable ultrasound Doppler measurements when assessing TIPS function (27, 41, 42). In fact, updated recommended guidelines for evaluating TIPS function have reverted to recurrence of the problem for which the TIPS was originally performed as grounds for revision (43). In contrast, changes in volume flow are straightforward to interpret. For example, if TIPS flow decreases and cardiac output is presumed unchanged, blood must be shunted elsewhere such as varices, which suggests a TIPS stenosis. In this case, decreased TIPS flow would be a realistic measure of TIPS failure.

Assessment of TIPS flow and function has been demonstrated using a 3D/4D SVF technique that provides an alternative objective measure of shunt patency and overcomes many limitations associated with traditional pulsed-wave Doppler. Traditional pulsed-wave Doppler is unable to reliably estimate volume flow due to subjective measurement of vessel diameter, assumption of circular shunt geometry, subjective Doppler angle correction, and assumption of a cylindrically symmetric flow profile. Volume flow measurements with the proposed method are independent of vessel geometry, angle, and flow profile. Bench top determinations of accuracy with the proposed method showed an error within 5% achieved after acquisition of 15 volumes in pulsatile flow conditions (36). Volume flow is expected to be a more robust metric for patency than flow velocity because flow must be conserved along the path of the shunt and therefore a measurement can be made anywhere along the TIPS.

Results of this preliminary study exhibit an inverse correlation between mean-normalized change in pre- and post-revision shunt volume flow and mean-normalized change in pre- and post-revision PSPG, which indicates that an increase in shunt volume flow corresponds with a decrease in PSPG (r2 = 0.51, P = 0.020). Therefore, relative change in shunt blood flow appears to be an acceptable surrogate for change in shunt PSPG for TIPS revision cases. Variability in the flow metric (error bars, Figure 4) is presumed due to biological variability in shunt flow.

Blood flow has an advantage over pressure in that one can perform the measurement in a standard diagnostic environment. A feasible clinical implementation would involve measurement of volume flow immediately following a successful TIPS revision, i.e., achieved PSPG <12 mmHg. Screening would then involve straightforward quantitative comparison of subsequent volume flow measurements to the baseline value to assess TIPS function.

TIPS volume flow measurements with the proposed 3D/4D method are in line with those presented in the literature (29–31). Comparison of pre-revision shunt flow for all 15 TIPS cases shows a preliminary threshold developing at 1534 mL/min below which TIPS may be recommended for revision depending on complementary clinical criteria. All normal TIPS cases in this study had flow above this threshold. The group comparison in Figure 5 illustrates promise for the proposed method given published sensitivities for standard Doppler methods, e.g., 35% (27). For a representative example, consider the results from patient 9, whose pre-revision flow was measured as 1910 ± 298.9 mL/min (mean ± standard deviation), which suggests a revision may be unnecessary. Based on traditional criteria, this patient was referred for revision. However, post-revision PSPG was unchanged and this outcome was reflected in post-revision flow which was measured as 1938 ± 355.9 mL/min. A follow-up ultrasound one month after revision showed a patent TIPS. This patient died five months after revision from cardiac-related issues.

An upper bound threshold above which all TIPS are considered normal could not be defined using the preliminary results in this study. Figure 5b shows three false-negative cases at the 1534 mL/min threshold defined above. Identifying such an upper bound threshold requires further study with a larger patient population. A patient with TIPS flow above the 1534 mL/min threshold will require additional clinical criteria to confirm normal TIPS function. In contrast, TIPS flow below the threshold would by itself suggest that a TIPS revision may be necessary. However, initial measurements with the proposed volume flow method should be used as a complementary or additive clinical criterion.

Although the proposed method is independent of all traditional pulsed-wave Doppler assumptions, the operator must still recognize the correct color/power gain and Doppler pulse repetition frequency (PRF) to avoid aliasing. In addition, the operator must ensure that the lateral-elevational c-surface fully intersects the shunt in cross section. Correct selection of color/power gain and PRF is necessary for any Doppler quantification and is therefore not unique to the proposed method.

This study had a few limitations. First, two revised cases were excluded from the linear regression analysis (Figure 4) and two cases, i.e., three data points, were excluded from the pre-revision volume flow comparison (Figure 5). Reasons for excluding these cases were justified due to a two-TIPS morphology and unusual contingencies in their data acquisition. Fortunately, results from these cases were outside the expected range and therefore the resultant linear regression showed a stronger correlation (r2 = 0.51, Figure 4b). Including these cases reduces the correlation and although the regression is less compelling, the correlation is still significant (P = 0.036, Figure 4a).

Second, the total acquisition time for one complete color Doppler data set consisting of 30 3D/4D image volumes required approximately 6–10 minutes, with each transducer sweep requiring a breath hold. This was a technical limitation because a mechanically-swept 3D ultrasound probe was used. However, 30 volumes were acquired because this study was interested in estimating reproducibility. In a clinical setting, an operator might be willing to make a measurement consisting of fewer acquisitions. For example, 10 acquisitions might only require 2–3 minutes. Further, a 2D electronic ultrasound array can acquire 3D image volumes more rapidly than a mechanically-swept 3D probe and the acquisition of 30 image volumes could be completed in seconds, i.e., one or two breath holds.

Third, there were limitations with the study inclusion criteria. Only patients scheduled for revision were recruited and therefore only three cases with non-revised TIPS were enrolled in the study. Future studies intend to include additional control cases to help strengthen statistical conclusions. In addition, study inclusion criteria should consider patient BMI. Acoustic access of the TIPS is limited in overweight patients which causes increased imaging depth and reduced Doppler power at depth.

In conclusion, volume flow measurement in TIPS using 3D/4D Doppler sonography provides a potential alternative to standard pulsed-wave Doppler metrics for evaluating shunt patency and identifying cases requiring revision. With further refinements, volume flow estimates can be incorporated as part of routine TIPS screening and evaluation. Ultimately, volume flow measurements could be applied toward other vascular conditions such as portal hypertension in liver and liver transplants to assess therapeutic outcome.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded in part by the Michigan Institute for Clinical & Health Research (National Institutes of Health grant UL1RR024986), University of Michigan Health System (Radiology seed grant), and a research grant from GE Healthcare.

References

- 1.Noldge G, Rossle M, Richter GM, Perarnau JM, Palmaz JC. Modelling the transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt using a metal prosthesis: requirements of the stent. Radiologe 1991; 31:102–107. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown RS Jr, Lake JR. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt as a form of treatment for portal hypertension: indications and contraindications. Adv Intern Med 1997; 42:485–504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Darcy M Minimally invasive therapy for portal hypertension. Probl Gen Surg 1999; 16:28–43. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Middleton WD, Teefey SA, Darcy MD. Doppler evaluation of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Ultrasound Q 2003; 19:56–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perarnau JM, Baju A, D’Alteroche L, Viguier J, Ayoub J. Feasibility and long-term evolution of TIPS in cirrhotic patients with portal thrombosis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2010; 22:1093–1098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Evaluation Darcy M. and management of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Am J Roentgenol 2012; 199:730–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Haskal ZJ, Pentecost MJ, Soulen MC, Shlansky-Goldberg RD, Baum RA, Cope C. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt stenosis and revision: early and midterm results. Am J Roentgenol 1994; 163:439–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lind CD, Malisch TW, Chong WK, et al. Incidence of shunt occlusion or stenosis following transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt placement. Gastroenterology 1994; 106:1277–1283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kerlan RK Jr, LaBerge JM, Gordon RL, Ring EJ. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: current status. Am J Roentgenol 1995; 164:1059–1066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.LaBerge JM, Somberg KA, Lake JR, et al. Two-year outcome following transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt for variceal bleeding: results in 90 patients. Gastroenterology 1995; 108:1143–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sterling KM, Darcy MD. Stenosis of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: presentation and management. Am J Roentgenol 1997; 168:239–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saxon RS, Ross PL, Mendel-Hartvig J, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt patency and the importance of stenosis location in the development of recurrent symptoms. Radiology 1998; 207:683–693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhuang ZW, Teng GJ, Jeffery RF, Gemery JM, Janne d’Othee B, Bettmann MA. Long-term results and quality of life in patients treated with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Am J Roentgenol 2002; 179:1597–1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bureau C, Garcia-Pagan JC, Otal P, et al. Improved clinical outcome using polytetrafluoroethylene-coated stents for TIPS: results of a randomized study. Gastroenterology 2004; 126:469–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vignali C, Bargellini I, Grosso M, et al. TIPS with expanded polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent: results of an Italian multicenter study. Am J Roentgenol 2005; 185:472–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hausegger KA, Karnel F, Georgieva B, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation with the Viatorr expanded polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent-graft. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2004; 15:239–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Charon JP, Alaeddin FH, Pimpalwar SA, et al. Results of a retrospective multicenter trial of the Viatorr expanded polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stent-graft for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2004; 15:1219–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rossi P, Salvatori FM, Fanelli F, et al. Polytetrafluoroethylene-covered nitinol stent-graft for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation: 3-year experience. Radiology 2004; 231:820–830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tripathi D, Ferguson J, Barkell H, et al. Improved clinical outcome with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic stent-shunt utilizing polytetrafluoroethylene-covered stents. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006; 18:225–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heinzow HS, Lenz P, Kohler M, et al. Clinical outcome and predictors of survival after TIPS insertion in patients with liver cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol 2012; 18:5211–5218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chong WK, Malisch TA, Mazer MJ, Lind CD, Worrell JA, Richards WO. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: US assessment with maximum flow velocity. Radiology 1993; 189:789–793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Surratt RS, Middleton WD, Darcy MD, Melson GL, Brink JA. Morphologic and hemodynamic findings at sonography before and after creation of a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt. Am J Roentgenol 1993; 160:627–630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dodd GD, Zajko AB, Orons PD, Martin MS, Eichner LS, Santaguida LA. Detection of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt dysfunction: value of duplex Doppler sonography. Am J Roentgenol 1995; 164:1119–1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Foshager MC, Ferral H, Nazarian GK, Castaneda-Zuniga WR, Letourneau JG. Duplex sonography after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS): normal hemodynamic findings and efficacy in predicting shunt patency and stenosis. Am J Roentgenol 1995; 165:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Feldstein VA, Patel MD, LaBerge JM. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: accuracy of Doppler US in determination of patency and detection of stenoses. Radiology 1996; 201:141–147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kanterman RY, Darcy MD, Middleton WD, Sterling KM, Teefey SA, Pilgram TK. Doppler sonography findings associated with transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt malfunction. Am J Roentgenol 1997; 168:467–472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Owens CA, Bartolone C, Warner DL, et al. The inaccuracy of duplex ultrasonography in predicting patency of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Gastroenterology 1998; 114:975–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Murphy TP, Beecham RP, Kim HM, Webb MS, Scola F. Long-term follow-up after TIPS: use of Doppler velocity criteria for detecting elevation of the portosystemic gradient. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1998; 9:275–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lafortune M, Martinet JP, Denys A, et al. Short- and long-term hemodynamic effects of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: a Doppler/manometric correlative study. Am J Roentgenol 1995; 164:997–1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lotterer E, Wengert A, Fleig WE. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt: short-term and long-term effects on hepatic and systemic hemodynamics in patients with cirrhosis. Hepatology 1999; 29:632–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Itkin M, Trerotola SO, Stavropoulos SW, et al. Portal flow and arterioportal shunting after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt creation. J Vasc Interv Radiol 2006; 17:55–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moser U, Vieli A, Schumacher P, Pinter P, Basler S, Anliker M. A Doppler ultrasound device for assessment of blood volume flow. Ultraschall Med 1992; 13:77–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rubin JM, Adler RS, Fowlkes JB, et al. Fractional moving blood volume: estimation with power Doppler US. Radiology 1995; 197:183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sun Y, Ask P, Janerot-Sjoberg B, Eidenvall L, Loyd D, Wranne B. Estimation of volume flow rate by surface integration of velocity vectors from color Doppler images. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 1995; 8:904–914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kripfgans OD, Rubin JM, Hall AL, Gordon MB, Fowlkes JB. Measurement of volumetric flow. J Ultrasound Med 2006; 25:1305–1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Richards MS, Kripfgans OD, Rubin JM, Hall AL, Fowlkes JB. Mean volume flow estimation in pulsatile flow conditions. Ultrasound Med Biol 2009; 35:1880–1891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinter SZ, Rubin JM, Kripfgans OD, et al. Three-dimensional sonographic measurement of blood volume flow in the umbilical cord. J Ultrasound Med 2012; 31:1927–1934. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kliewer MA, Hertzberg BS, Heneghan JP, et al. Transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS): effects of respiratory state and patient position on the measurement of Doppler velocities. Am J Roentgenol 2000; 175:149–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ho H, Sorrell K, Peng L, Yang Z, Holden A, Hunter P. Hemodynamic analysis for transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) in the liver based on a CT-image. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2013; 32:92–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sheiman RG, Vrachliotis T, Brophy DP, Ransil BJ. Transmitted cardiac pulsations as an indicator of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt function: initial observations. Radiology 2002; 224:225–230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Haskal ZJ, Carroll JW, Jacobs JE, et al. Sonography of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts: detection of elevated portosystemic gradients and loss of shunt function. J Vasc Interv Radiol 1997; 8:549–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sanyal AJ, Freedman AM, Luketic VA, et al. The natural history of portal hypertension after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts. Gastroenterology 1997; 112:889–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Boyer TD, Haskal ZJ. The role of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) in the management of portal hypertension: update 2009. Hepatology 2010; 51:306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]