Abstract

Objective

Twin studies suggest that genetic factors contribute to continuity in mental health problems and environmental factors are the major contributor to developmental change. We investigated the influence of psychiatric risk alleles on early-onset mental health trajectories and whether these were subsequently modified by exposure to childhood victimization.

Method

The sample was a prospective UK population-based cohort, the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. Developmental trajectories in childhood (approximately ages 4 to 8 years) and adolescence (approximately ages 12 to 17 years) were estimated for emotional problems. Psychiatric risk alleles were indexed by polygenic risk scores (PRS) for schizophrenia using genome-wide association study results from the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Chronic peer victimization in late childhood (ages 8.5 and 10.5 years) was assessed as an index of environmental exposure. Individuals with sufficient data on emotional problems, PRS and victimization were included in the main analyses: N=3988.

Results

Higher schizophrenia PRS were associated with a trajectory of early-onset increasing emotional problems (OR=1.18 (1.02-1.36)) compared to a trajectory of low-stable emotional problems. Subsequent exposure to victimization increased the likelihood of transitioning from a low-stable emotional problems trajectory during childhood (before exposure) to an increasing trajectory in adolescence (after exposure) (OR=2.59 (1.48-4.53)).

Conclusions

While the early development of emotional problems was associated with genetic risk (schizophrenia risk alleles), the subsequent course of emotional problems for those who might otherwise have remained on a more favorable trajectory was altered by exposure to peer victimization, which is a potentially modifiable environmental exposure.

Most psychiatric disorders, regardless of when first manifest, originate in childhood (1). However early childhood problems are not associated with later mental health outcomes for all - there is change as well as continuity across development (1). Twin studies consistently show that continuity in mental health problems across time is highly heritable (2, 3). This suggests that genetic factors make an important contribution to developmental trajectories. However twin studies show that environmental factors are a major contributor to change (3, 4). Identifying potentially malleable environmental factors that may alter the developmental course of heritable mental health problems is an important step towards guiding prevention strategies.

Molecular genetic studies have revealed that while the genetic architecture of psychiatric disorders is complex, it is now possible to assign to individuals a biologically valid indicator of common variant genetic liability for that phenotype (polygenic risk score, PRS) (5). To date, genetic findings in schizophrenia have led the field of PRS research, largely reflecting the relatively high power of genome wide association studies of that disorder (6). PRS derived from schizophrenia risk alleles predicts increased liability not only to that disorder but also other adult psychiatric disorders, for example major depression, and to mental health and neurodevelopmental traits in childhood (7, 8). Associations between schizophrenia PRS and anxiety/emotional problems have now been observed across the lifespan - in childhood, adolescence and adult life (8–11). These cross-sectional observations suggest that schizophrenia risk alleles may contribute to the trajectories of emotional problems from an early age, although this has not yet been tested directly. However, genetics alone cannot explain the developmental course of emotional problems (1). Psychosocial stressors also contribute risk; some are particularly prevalent in childhood (12). An example is chronic childhood peer victimization, a common social stressor in childhood that contributes to subsequent emotional problems in childhood and later adult life (13–18). Being bullied has been found to be associated with childhood emotional symptoms even when allowing for genetic confounding (15, 16, 18). Investigating genetic and environmental risk factors together is important to gain understanding of how these factors simultaneously affect the longitudinal course of mental health problems.

In this paper, we use a large prospective, population-based cohort, ALSPAC, that underwent the same repeated mental health assessments from ages 4 to 17 years, to test specific hypotheses concerning the association of schizophrenia PRS and childhood victimization with emotional problem trajectories. We postulated first that schizophrenia risk alleles (PRS) contribute to early-onset emotional problems that remain on an unfavorable trajectory. Second, that chronic peer victimization in late childhood would modify early trajectories by increasing the likelihood of transitioning from a low symptom trajectory in childhood (before exposure) to an elevated trajectory in adolescence (after exposure). We also explored the impact of the presence/absence of victimization for those already on an elevated trajectory in early childhood.

Method

Sample

The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) is a well-established prospective, longitudinal birth cohort study. The enrolled core sample consisted of 14,541 mothers living in Avon, England, who had expected delivery dates of between 1st April 1991 and 31st December 1992. Of these pregnancies 13,988 children were alive at 1 year. When the oldest children were approximately 7 years of age, the sample was augmented with eligible cases who had not joined the study originally, resulting in enrollment of 713 additional children. The resulting total sample size of children alive at 1 year was N=14,701. Genotype data were available for 8,365 children following quality control. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the ALSPAC Ethics and Law Committee and the Local Research Ethics Committees. Full details of the study, measures and sample can be found elsewhere (19, 20). Please note that the study website contains details of all the data that is available through a fully searchable data dictionary (http://www.bris.ac.uk/alspac/researchers/data-access/data-dictionary). Where families included multiple births, we included the oldest sibling.

Emotional problems

Emotional problems were assessed using the parent-rated 5-item emotional problems subscale (range 0-10) of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) (21) that includes primarily anxiety items (often complains of headaches; many worries; often unhappy, downhearted; nervous or clingy in new situations; many fears, easily scared). ‘Childhood’ data were collected at ages 47, 81 and 97 months (approximately age 4 to 8 years) and ‘adolescent’ data were collected at ages 140, 157 and 198 months (approximately age 12 to 17 years).

Polygenic risk scores

Schizophrenia polygenic risk scores (PRS) were generated as the weighted mean number of disorder risk alleles in approximate linkage equilibrium (r-square<0.25), derived from dosage data of 1,813,169 imputed autosomal SNPs using standard procedures (7). Risk alleles were defined as those associated with case-status in the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium (PGC) analyses of schizophrenia (35,476 cases and 46,839 controls) at a threshold of p<0.05 as this maximally captures phenotypic variance (6). Associations across a range of p-thresholds are shown in Figure SF1 in the online data supplement. Genotyping details, as well as full methods for generating the PRS can be found elsewhere (8).

Peer victimization

Peer victimization was assessed by interviews with the children using a 9-item modified version of the bullying and friendship interview schedule (13, 22) that asked about different types of overt and relational victimization experienced in the past six months. Data were collected at ages 8.5 and 10.5 years (after the ‘childhood’ and before the ‘adolescent’ emotional problems assessments). Individuals who reported having been victim to any of the items “frequently” or “very frequently” (several times a month/week) at both ages were classified as having been exposed to (chronic) peer victimization (11.6% of the sample). Those who reported being victims “seldom” or “never” for all items at either age were categorized as not having been exposed to (chronic) peer victimization.

Statistical analysis

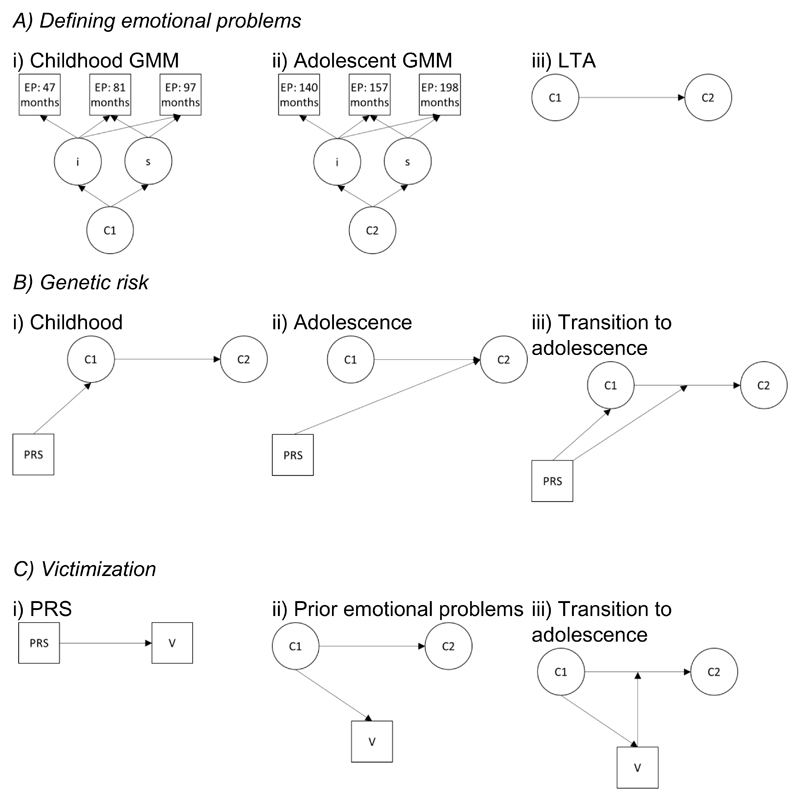

Analyses were conducted in several steps – depicted in Figure 1 and the final model in Figure 2. We modelled emotional problem trajectories by fitting Growth Mixture Models (GMM) separately for (a) the three childhood time-points, (b) the three adolescent time-points. Separate models for childhood and adolescence were fit to enable investigation of trajectory change before and after exposure to victimization. GMM groups individuals into trajectory classes (categories) based on patterns of growth (change) (23). Grouping individuals enabled us to investigate whether exposure to victimization was associated with transitioning from low emotional problems in childhood to having problems in adolescence. A latent class approach enabled us to identify unmeasured probabilistic subgroups (classes) based on the developmental patterns (trajectories) from repeated measures of observed variables (emotional problems). Starting with a single k-class solution, k+1 solutions were fitted until the optimum solution was reached. GMM solutions were selected based on fit indices (see online data supplement).

Figure 1.

Analysis steps

GMM=growth mixture model, LTA=latent transition analysis, EP=emotional problems, i=intercept, s=slope, C1=class 1 (childhood), C2=class 2 (adolescence) PRS = schizophrenia polygenic risk scores, V=victimization

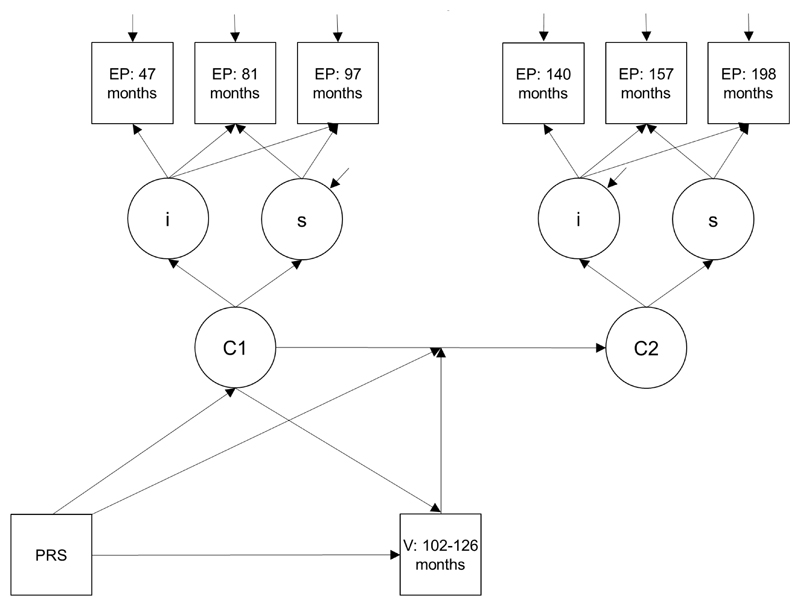

Figure 2.

Final model: associations between PRS, victimization and transition between childhood and adolescent emotional problems classes

EP=emotional problems, PRS=polygenic risk score, V=victimization, i=intercept, s=slope, C1=class 1 (childhood), C2=class 2 (adolescence).

Once trajectory classes had been defined, we assessed whether schizophrenia PRS predicted childhood and adolescent trajectory classes. We also checked for associations between schizophrenia PRS and child-reports of victimization.

Next, we examined transitions between childhood and adolescent emotional problem classes (i.e. before and after exposure to victimization). These were modelled by latent transition analysis using a bias-adjusted 3-step approach, which accounts for measurement error in class assignment (24). Measurement invariance between the childhood and adolescent trajectories was not assumed, given possible differences in longitudinal patterns (25).

We tested whether schizophrenia PRS and victimization were associated with change/transition in emotional problem trajectory class (from before exposure to victimization in childhood to after exposure in adolescence) (26). Testing association with transition combines the direct effect of schizophrenia PRS and victimization on adolescent trajectory classes and the moderating effect of schizophrenia PRS and victimization on the association between the childhood and adolescence classes.

Sensitivity analyses were conducted (a) including potential confounders, (b) excluding individuals who (according to an earlier parent-report measure) were exposed to prior peer victimization (before the self-reported victimization assessment at age 8.5 years), and (c) assessing the impact of missing data (see below). Full details of the sensitivity analyses are given in the online data supplement.

All analyses were conducted in Mplus using a maximum likelihood parameter estimator for which standard errors are robust to non-normality (MLR) (27). Binary/multinomial logistic regressions were used as appropriate and associations are presented as odds ratios. Multinomial logistic regression technically estimates multinomial odds ratios (or relative risk ratios); however, we refer to effects as odds ratios (usually used for two exhaustive categories) throughout the results section for clarity.

Missing data

Details of the available sample sizes at each step of analysis are shown in shown in Figure SF2 in the online data supplement. The starting sample size included individuals with data on emotional problems for at least two of the three relevant time-points in either childhood (N=8425) or adolescence (N=7018). These individuals were included in the GMMs that were used to derive the emotional problems classes; GMM were conducted in Mplus using full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) (27). GMM data in both childhood and adolescence were available for N=6146, of whom 75% had genetic data and 83% had victimization data: 65% had both genetic and victimization data and thus formed our ‘main sample’ (N=3988). Inverse probability weighting (28) was used to assess the impact of missing data, whereby observations were weighted based on measures assessed in pregnancy that were predictive of variables in the analysis and/or inclusion in the main sample (see online data supplement).

Results

Modelling emotional problem developmental trajectories

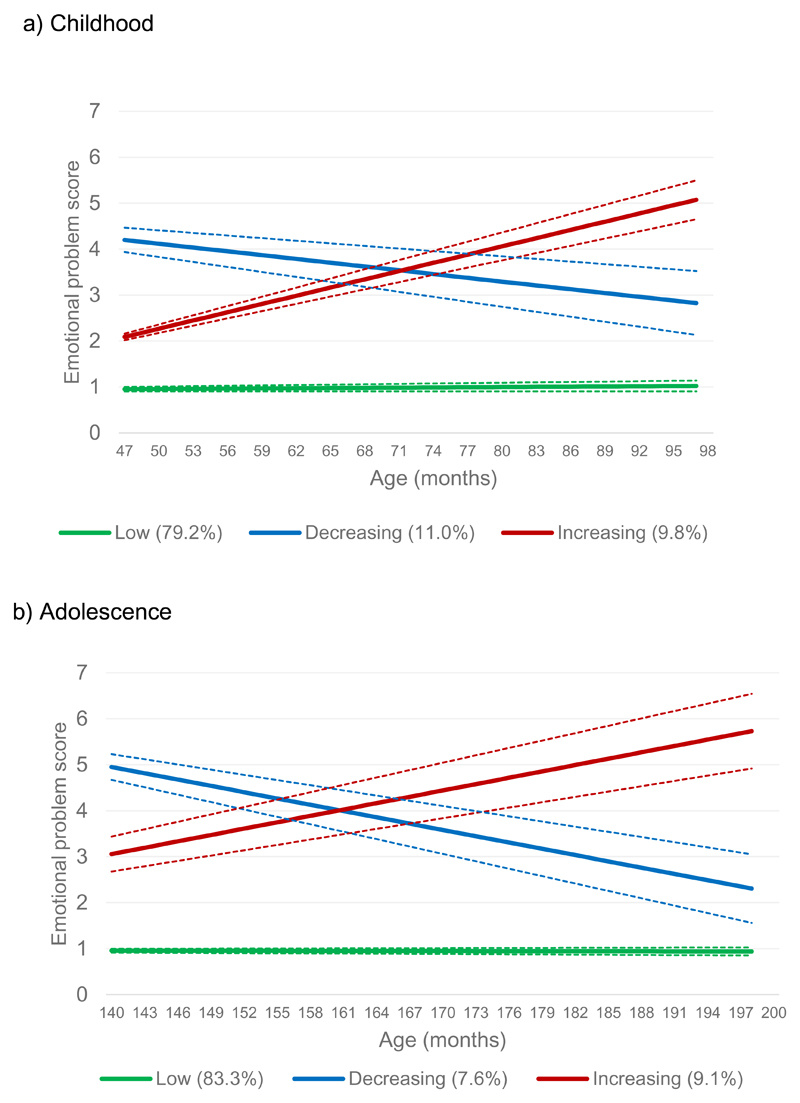

Descriptive statistics including gender differences are shown in Table ST1 in the online data supplement. As shown in Figure 3, in both childhood (N=8425) and adolescence (N=7018), we observed three emotional problem trajectory classes: low (79.2% in childhood, 83.3% in adolescence), decreasing (11.0% in childhood, 7.6% in adolescence) and increasing (9.8% in childhood, 9.1% in adolescence). Subsequent analyses of trajectories focus on the (less favorable) increasing class compared to the (most favorable) low emotional problems class.

Figure 3.

Emotional problem class by age

Mean trajectories with 95% confidence intervals for each class

There was strong evidence for an association between childhood and adolescent emotional problem trajectory classes, although confidence interval were wide: compared to the low class in childhood, a much higher proportion of the individuals in the childhood increasing class were also in the increasing class in adolescence (OR=17.07 (10.30-28.30), p<0.001). All transition probabilities for the latent transition analysis are shown in Figure SF3 in the online data supplement.

Schizophrenia PRS and emotional problem developmental trajectories

Higher schizophrenia PRS were associated with an elevated likelihood of being in the increasing emotional problem trajectory class in childhood (OR=1.18 (1.02-1.36), p=0.030). Despite the adolescent trajectory classes being strongly associated with prior childhood trajectories, schizophrenia PRS still showed some independent association with emotional problem trajectories in adolescence (OR=1.17 (1.00-1.36), p=0.050), when compared to the low class.

Self-reported victimization exposure

Victimization exposure in late childhood was predicted by earlier, childhood emotional problems - the increasing childhood trajectory class (OR=1.79 (1.21-2.66), p=0.004). However schizophrenia PRS were not associated with exposure to child-reported chronic victimization (OR=0.95 (0.86-1.04), p=0.292).

Schizophrenia PRS and victimization: associations with trajectory changes

Schizophrenia PRS were not associated with transitioning from the low childhood trajectory class to the increasing trajectory class in adolescence (OR=1.04 (0.81-1.34), p=0.758).

Chronic peer victimization however was associated with transition from the low trajectory class in childhood (before exposure) to the increasing trajectory class in adolescence (after exposure; OR=2.59 (1.48-4.53) p=0.001). This association held when schizophrenia PRS were included in the model (OR=2.57 (1.46-4.52), p=0.001).

Post-hoc analyses suggested that for those (already) in the childhood increasing trajectory class, victimization did not alter the trajectory in adolescence as it was not associated with transitions for this trajectory class (overall Wald χ2(2)=3.61, p=0.165: adolescent increasing vs. low OR=2.51 (0.54-11.68); decreasing vs. low OR=4.26 (0.94-19.39)).

Sensitivity analyses

Including sex, social class and maternal depression, home ownership, education and marital status as covariates revealed a similar pattern of results (see Table TF3 in the online data supplement).

Excluding individuals who were exposed to prior peer victimization (maternal reports at ages 4-8 years) also revealed a similar pattern of results, with the exception that the association between victimization and transitioning from the low to increasing class was reduced (OR=1.90 (0.90-4.00), p=0.093; see online data supplement). Thus, the observed association between chronic peer victimization and transitioning from a low to increasing class may be driven by individuals exposed to particularly chronic victimization (i.e. which occurred in early childhood as well as at ages 8.5 and 10.5 years).

Finally, using inverse probability weighting to assess the impact of missing data did not change the interpretation of results (see online data supplement).

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the contribution of schizophrenia risk alleles to developmental trajectories of emotional problems across childhood and adolescence in the general population. We also set out to assess whether early developmental trajectories could be shifted by an environmental stressor - peer victimization. Specifically, we tested the hypotheses that schizophrenia risk alleles, indexed by PRS, would be associated with an elevated trajectory of early-onset emotional problems that persisted through adolescence, and that exposure to chronic peer victimization would alter the subsequent developmental course of trajectories. Our findings suggest that schizophrenia risk alleles contribute to an increasing trajectory of emotional problems in early childhood and adolescence. Later environmental risk exposure - in this case chronic peer victimization – contributes to change over time. The findings suggest there are at-least two routes into an increasing trajectory of emotional problems during adolescence. The first is via genetically influenced childhood-onset emotional problems - which show strong continuity to adolescent emotional problems - and the second is via exposure to peer victimization, which alters the developmental course of individuals who are initially on a low risk trajectory to a less favorable trajectory.

The results from this study supported our first hypothesis that schizophrenia PRS contribute to a developmental trajectory of increasing emotional problems that begin early in childhood. However, the PRS did not explain the transition between childhood and adolescent trajectories and developmental trajectories during adolescence were most strongly predicted by earlier childhood trajectories. This suggests that PRS impacts during adolescence are predominantly explained via association with earlier childhood trajectories; they do not contribute substantially to changes in emotional problem trajectories. This is consistent with cross-sectional genetics research, including in this sample, that has shown associations between schizophrenia PRS and emotional problems in childhood, adolescence and adulthood (8–11) and with twin studies, which infer genetic contribution to continuity in mental health problems (2). Taken together these observations suggest that interventions aimed at improving developmental trajectories for those at elevated genetic risk of mental health problems likely need to begin very early in life-in the pre-school years.

The findings also suggest that exposure to chronic peer victimization in late childhood further shapes the developmental course of emotional problems. Specifically, exposure to victimization during childhood that was not predicted by schizophrenia PRS altered subsequent adolescent trajectories. We observed an increased likelihood of individuals transitioning from a consistently low emotional problem trajectory in childhood (before victimization exposure) to a trajectory of increasing emotional problems in adolescence (after exposure). Twin studies have repeatedly highlighted environmental factors as important contributors to change in mental health over time (4), and chronic childhood peer victimization is considered as a robust risk factor for emotional problems and depression even when using genetically-sensitive twin designs (13, 14).

We also observed that exposure to subsequent chronic victimization was associated with prior increasing emotional problems in childhood. Psychopathology is known to increase the likelihood of exposure to environmental risk factors including victimization (29). However, post-hoc analyses found that victimization was not associated with change in emotional problems for those who were on the less favorable trajectory of (increasing) emotional problems in childhood. This suggests that while experiencing chronic victimization is associated with developing new emotional problems in adolescence, it may not drive the persistence of very early-onset chronic difficulties – i.e. eliminating peer victimization may not prevent ongoing problems for those who are already on a trajectory of increasing emotional problems, although further work testing this hypothesis is required. Nevertheless, in-line with previous research (30), the findings suggest that these children with early-onset emotional problems may benefit from monitoring of peer relations. An interesting direction for future research would be to investigate whether protective environmental factors can alter the course of early emotional problems trajectories away from later emotional problems (31).

This study has a number of strengths, including the integration of molecular genetic and epidemiological approaches to investigate the impact of both genetic and environmental risks on developmental trajectories. However, our findings should be considered in light of some limitations. First, ALSPAC is a longitudinal birth cohort study that suffers from non-random attrition, whereby individuals with higher levels of psychopathology and PRS are less likely to be retained in the study (32, 33). Analyses using inverse probability weighting to assess the impact of missing data did not change the interpretation of results, suggesting this has not made a major impact on our results. Despite a large sample for analysis (N=3988), sample size may have impacted our ability to detect other trajectory classes, for example those with persistently high problems, which may be reflected in our wide confidence intervals when testing for associations with the different trajectories. This could also have been the result of running separate models for childhood and adolescence, although other studies that have examined trajectories of emotional problems across childhood/adolescence have also not identified a ‘persistent’ trajectory (34). As only three time-points for each of the growth models were available, we were also only able to model linear change in emotional problems – other patterns may better reflect developmental changes. We also used a parent-report questionnaire measure to assess emotional problems, which may not generalize to diagnoses, although the SDQ is a well-validated measure (21) and our classes were associated with depression diagnosis at age 18 years (see online data supplement). Moreover, using the same measure and informant is a strength for assessing developmental trajectories as otherwise change could be explained by measurement differences. In addition, schizophrenia PRS currently explains a minority of common variant liability to the disorder (6) and the effect sizes we observed are typical for this kind of work (9). For example – adopting an approach previously used to quantify effects (35), individuals in the top 2.5% for schizophrenia PRS would have a roughly 36% increased odds of having increasing, compared to low, emotional problems in childhood. Thus, PRS should be regarded as indicators of genetic liability rather than as predictors. We did not find schizophrenia PRS was associated with child-reported victimization. However we cannot completely rule out the possibility of genetic confounding; findings might differ depending on who is reporting the victimization (here we use child reports, rather than parent reports), the severity of bullying, and also other types of genetic variants could still contribute to links between victimization and emotional problems.

Finally, our analyses and hypotheses were shaped by previous work (16) and because of the availability in ALSPAC of three emotional symptoms assessments prior to exposure to victimization and three assessments after exposure. However our methods could be used in other cohorts to address developmental questions relevant to other environmental exposures, such as life events (36) and for additional psychiatric outcomes (18). Future work investigating how genetic risk variants work together with environmental risk - and protective – factors, on a range of psychiatric outcomes will be needed, although rigorous methods are needed to know which environmental risk factors are likely causal (37, 38).

We found that a higher burden of schizophrenia risk alleles is associated with a developmental trajectory of increasing emotional problems that begins in early childhood. Exposure to chronic peer victimization in late childhood alters emotional problem trajectories, whereby individuals in a stable-low state across childhood transition to a trajectory of increasing emotional problems in adolescence.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the members of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium for the publically available data used as the discovery sample in this manuscript. We are extremely grateful to all the families who took part in this study, the midwives for their help in recruiting them, and the whole ALSPAC team, which includes interviewers, computer and laboratory technicians, clerical workers, research scientists, volunteers, managers, receptionists and nurses. The UK Medical Research Council and the Wellcome Trust (102215/2/13/2) and the University of Bristol provide core support for ALSPAC. GWAS data was generated by Sample Logistics and Genotyping Facilities at the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute and LabCorp (Laboratory Corporation of America) using support from 23andMe. This work was primarily supported by the Medical Research Council (MR/M012964/1) and additionally by Medical Research Council Centre (G0800509) and Program Grants (G0801418). The Medical Research Council and Alcohol Research UK provided additional support for GH and JH (MR/L022206/1). LA is the Mental Health Leadership Fellow for the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) in the UK.

Footnotes

Disclosures

All authors report reports no competing interests.

References

- 1.Rutter M, Kim-Cohen J, Maughan B. Continuities and discontinuities in psychopathology between childhood and adult life. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47(3–4):276–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ronald A. Is the child 'father of the man'? evaluating the stability of genetic influences across development. Dev Sci. 2011;14(6):1471–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2011.01114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hannigan L, Walaker N, Waszczuk M, McAdams T, Eley T. Aetiological influences on stability and change in emotional and behavioural problems across development: a systematic review. Psychopathology review. 2017;4(1):52. doi: 10.5127/pr.038315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rutter M, Pickles A, Murray R, Eaves L. Testing hypotheses on specific environmental causal effects on behavior. Psychol Bull. 2001;127(3):291–324. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.3.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sullivan PF, Agrawal A, Bulik CM, Andreassen OA, Børglum AD, Breen G, et al. Psychiatric Genomics: An Update and an Agenda. Am J Psychiat. 2018;175(1):15–27. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.17030283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Biological insights from 108 schizophrenia-associated genetic loci. Nature. 2014;511(7510):421–7. doi: 10.1038/nature13595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cross-Disorder Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Identification of risk loci with shared effects on five major psychiatric disorders: a genome-wide analysis. The Lancet. 2013;381(9875):1371–9. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)62129-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Riglin L, Collishaw S, Richards A, Thapar A, Maughan B, O’Donovan M, et al. Schizophrenia risk alleles and neurodevelopmental outcomes in childhood: a population-based cohort study. Lancet Psychitary. 2017;4(1):57–62. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30406-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones HJ, Stergiakouli E, Tansey KE, Hubbard L, Heron J, Cannon M, et al. Phenotypic manifestation of genetic risk for schizophrenia during adolescence in the general population. JAMA psychiatry. 2016;73(3):221–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.3058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nivard MG, Gage SH, Hottenga JJ, van Beijsterveldt CE, Abdellaoui A, Bartels M, et al. Genetic Overlap Between Schizophrenia and Developmental Psychopathology: Longitudinal and Multivariate Polygenic Risk Prediction of Common Psychiatric Traits During Development. Schizophr Bull. 2017;6(21):1197–207. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbx031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riglin L, Collishaw S, Richards A, Thapar AK, Rice F, Maughan B, et al. The impact of schizophrenia and mood disorder risk alleles on emotional problems: investigating change from childhood to middle age. Psychol Med. 2017:1–6. doi: 10.1017/S0033291717003634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Silberg J, Rutter M, Neale M, Eaves L. Genetic moderation of environmental risk for depression and anxiety in adolescent girls. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2001;179(2):116–21. doi: 10.1192/bjp.179.2.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bowes L, Joinson C, Wolke D, Lewis G. Peer victimisation during adolescence and its impact on depression in early adulthood: prospective cohort study in the United Kingdom. BMJ : British Medical Journal. 2015;350 doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takizawa R, Maughan B, Arseneault L. Adult health outcomes of childhood bullying victimization: evidence from a five-decade longitudinal British birth cohort. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(7):777–84. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Silberg JL, Copeland W, Linker J, Moore AA, Roberson-Nay R, York TP. Psychiatric outcomes of bullying victimization: a study of discordant monozygotic twins. Psychol Med. 2016;46(9):1875–83. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716000362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arseneault L, Milne BJ, Taylor A, Adams F, Delgado K, Caspi A, et al. Being bullied as an environmentally mediated contributing factor to children's internalizing problems: a study of twins discordant for victimization. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(2):145–50. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowes L, Maughan B, Ball H, Shakoor S, Ouellet-Morin I, Caspi A, et al. Chronic bullying victimization across school transitions: the role of genetic and environmental influences. Dev Psychopathol. 2013;25(2):333–46. doi: 10.1017/S0954579412001095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singham T, Viding E, Schoeler T, et al. Concurrent and longitudinal contribution of exposure to bullying in childhood to mental health: The role of vulnerability and resilience. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(11):1112–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Boyd A, Golding J, Macleod J, Lawlor DA, Fraser A, Henderson J, et al. Cohort Profile: The 'Children of the 90s'-the index offspring of the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. International journal of epidemiology. 2013;42(1):111–27. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fraser A, Macdonald-Wallis C, Tilling K, Boyd A, Golding J, Davey Smith G, et al. Cohort Profile: The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children: ALSPAC mothers cohort. International journal of epidemiology. 2013;42(1):97–110. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goodman R. The Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: A research note. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 1997;38(5):581–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1997.tb01545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolke D, Woods S, Stanford K, Schulz H. Bullying and victimization of primary school children in England and Germany: prevalence and school factors. Br J Psychol. 2001;92(Pt 4):673–96. doi: 10.1348/000712601162419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Muthen B, Muthen LK. Integrating person-centered and variable-centered analyses: Growth mixture modeling with latent trajectory classes. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24(6):882–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Auxiliary variables in mixture modeling: Three-step approaches using Mplus. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal. 2014;21(3):329–41. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maughan B, Collishaw S. Development and psychopathology: A life course perspective. In: Thapar A, Pine DS, Leckman JF, Scott S, Snowling MJ, Taylor E, editors. Rutter’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lanza ST, Collins LM. A new SAS procedure for latent transition analysis: transitions in dating and sexual risk behavior. Dev Psychol. 2008;44(2):446. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Seventh ed. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén &Muthén; 1998-2012. Mplus User's Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Seaman SR, White IR. Review of inverse probability weighting for dealing with missing data. Stat Methods Med Res. 2013;22(3):278–95. doi: 10.1177/0962280210395740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arseneault L, Bowes L, Shakoor S. Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems: 'much ado about nothing'? Psychol Med. 2010;40(5):717–29. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709991383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bowes L, Arseneault L, Maughan B, Taylor A, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. School, neighborhood, and family factors are associated with children's bullying involvement: a nationally representative longitudinal study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(5):545–53. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e31819cb017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Collishaw S, Hammerton G, Mahedy L, Sellers R, Owen MJ, Craddock N, et al. Mental health resilience in at-risk adolescents. Lancet Psychiatry. 2016;3(1):49–57. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00358-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wolke D, Waylen A, Samara M, Steer C, Goodman R, Ford T, et al. Selective drop-out in longitudinal studies and non-biased prediction of behaviour disorders. The British Journal of Psychiatry. 2009;195(3):249–56. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.108.053751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Martin J, Tilling K, Hubbard L, Stergiakouli E, Thapar A, Smith GD, et al. Association of Genetic Risk for Schizophrenia With Nonparticipation Over Time in a Population-Based Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2016 doi: 10.1093/aje/kww009. kww009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nivard MG, Lubke GH, Dolan CV, Evans DM, St Pourcain B, Munafo MR, et al. Joint developmental trajectories of internalizing and externalizing disorders between childhood and adolescence. Dev Psychopathol. 2017;29(3):919–28. doi: 10.1017/S0954579416000572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kendler KS. The schizophrenia polygenic risk score: To what does it predispose in adolescence? JAMA Psychiatry. 2016;73(3):193–4. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Eley TC, Stevenson J. Specific Life Events and Chronic Experiences Differentially Associated with Depression and Anxiety in Young Twins. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2000;28(4):383–94. doi: 10.1023/a:1005173127117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rutter M. Identifying the Environmental Causes of Disease: How Should We Decide what to Believe and when to Take Action?: an Academy of Medical Sciences Working Group Report: Academy of Medical Sciences. 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 38.Thapar A, Rutter M. Using natural experiments and animal models to study causal hypotheses in relation to child mental health problems. In: Thapar A, Pine DS, Leckman JF, Scott S, Snowling MJ, Taylor E, editors. Rutter's Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. Sixth ed. Oxford: Wiley Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.