Abstract

The large phagocytic load that confronts the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) is thought to play a possible role in the pathogenesis of age related macular degeneration (AMD) that afflicts both humans and monkeys. Our knowledge of how RPE degrades phagosomes and other intra-cellular material by lysosomal action is still rudimentary. In this paper we examine organelles that play a role in this process, melanosome, lysosomes and phagosomes, in the RPE of young and old rhesus monkeys in order to better understand lysosomal autophagy and heterophagy in the RPE and its possible role in AMD.

We used electron microscopy to detect and describe the characteristics of melanosomes and lysosomelike organelles in the macular RPE of rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) that were 1, 6, 24, 24, 26 and 35 years of age. The measurements include the number, shape and size of these organelles located in the basal, middle and apical regions of RPE cells. Phaagosomes were also examined but not counted or measured for size or shape because of their rarity.

Melanosomes were homogeneously dark with a circular or elliptical shape and decreased in number with age. Smaller melanosomes were more common at the basal side of the RPE. Among the small melanosomes, we found an organelle that was losing melanin in varying degrees; in some cases was nearly devoid of melanin. Because of the melanin loss, we considered this organelle to be a unique type of autophagic melano-lysosome, which we called a Type 1 lysosome. We found another organelle, more canonically lysosomal, which we called a Type 2 lysosome. This organelle was composed of a light matrix containing melanosomes in various stages of degradation. Type 2 lysosomes without melanosomes were rare. Type 2 lysosomes increased while Type 1 decreased in number with age. Phagosomes were rare in both young and old monkeys. They made close contact with Type 2 lysosomes which we considered responsible for their degradation.

Melanosomes are being lost from monkey RPE with age.Much of this loss is carried out by two types of lysosomes. One, not defined as unique before, appears to be autophagic in digesting its own melanin; it has been called a Type 1 lysosome. The other, a more canonical lysosome, is both heterophagic in digesting phagosomes and autophagic in digesting local melanosomes; it has been called a Type 2 lysosome. Type 1 lysosomes decrease while type 2 lysosomes increase with age. The loss of melanin is considered to be detrimental to the RPE since it reduces melanin’s protective action against light toxicity and oxidative stress. Phagosomes appear to be degraded by membrane contacts with Type 2 lysosomes. The loss of melanin and the buildup of Type 2 lysosomes occur at an earlier age in monkeys than humans implying that a greater vulnerability to senescence accelerates the rate of AMD in monkeys.

Keywords: retinal pigment epithelium, melanosomes, lysosomes, phagosomes, rhesus monkeys, age related macular degeneration

1. Introduction

A possible factor in the pathogenesis of age related macular degeneration is the large age-related buildup of lipofuscin containing melano- lysosomes in the RPE. The processes underlying this accumulation are not understood. One explanation posits that this post-mitotic epithelium faces such a large phagosomal load from the shedding of tips of photoreceptor outer segments that it fails to dissolve them completely, thus allowing waste material to accumulate with time. The failure to dissolve this waste material may also be due to toxic substances in the phagocytized outer segments that impede lysosomal function (Schutt et al., 2000, 2001; Finnemann et al., 2002; Bergmann et al., 2004; Radu et al., 2004; Sparrow and Boulton, 2005; Strauss, 2005). In order to better understand the organizational features accompanying the buildup of material in lysosomes of RPE, we have examined the ultra-structure of organelles, melanosomes, lysosomes and phagosomes, in the RPE cytoplasm of young and old rhesus monkeys, nonhuman primates with a human-like retina and a high prevalence of AMD (Gouras et al., 2008a). With an average lifespan of 25 years and maximum of 40 years, rhesus monkeys age at a rate of approximately 3 years to one compared to a human.

2. Methods

After euthanasia, eyes from six rhesus monkeys (1, 6, 24, 24, 26 and 35 years of age) were removed within minutes and fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde + 0.45% glutaraldehyde. Diffusion of fixativewas facilitated by piercing the eye at the limbus with an 18 gauge needle and injecting 1.0 ml of fixative into the vitreous. After a week or longer in fixative the eyes were washed with a balanced salt solution and dissected with the aid of a surgical microscope. A square macular segment centered on the fovea was cut out, dehydrated, osmicated and embedded in epon blocks. The blocks were sectioned, stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate and examined by transmission electron microscopy using a Zeiss 190 or a Jeol 1200 instrument. Measurements were made of the number and size of melanosomes and lysosome-like organelles. Size was determined by measuring the long axis of each organelle. We examined 8–10 adjacent RPE cells covering approximately equal areas for each animal at a magnification of 15,000×. Measurements were made within the basal, middle and apical regions of each RPE cell; the basal region extended from the basal in folds to the midposition of a nearby nucleus; the region from the middle of the nucleus to the apical membrane was divided in half; the lower half was the middle region, the upper half the apical region. Each region comprised approximately one-third of the cell. Melanosomes between outer segments were not measured. We expressed the measurements in organelles/micron2. Digitized images were viewed with an Adobe Photoshop C3 program. Adjusting image brightness helped to distinguish lysosomes from melanosomes. Increasing brightness revealed particulate bodies within lysosomes but not within melanosomes which remained homogeneously dark at high brightness levels. All procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the Oregon Health and Science University and conformed to the Principles of Laboratory Animal Care (NIH publication No. 85-23, revised 1985).

3. Results

3.1. Melanosomes

Fig. 1 shows pure melanosomes. They are round or elliptical and remain homogeneously dark under bright illumination. The larger elliptical melanosomes were usually near the apical side; smaller rounder ones tended to be at the basal side of the RPE. Fig. 2 shows the size distribution of melanosomes in macular RPE for two of the younger and two of the older monkeys. More melanosomes were present in the RPE of the younger than the older monkeys.

Fig. 1.

Shows melanosomes in monkey RPE. The calibration, lower right, indicates 0.5 microns.

Fig. 2.

Compares the length of the long axis (abscissa) and the number (ordinate) of melanosomes in the basal, middle and apical parts of the RPE cell of the 1, 6, 24 and 35 year old monkeys.

3.2. A unique lysomal-like organelle

Fig. 3 (white arrows) shows a class of organelles that have not been singled out previously as unique. They were often found in close association with typical, homogeneously dark melanosomes of similar size. They were distinguished from typical melanosome, however, by light areas, present usually near the center of the organelle. In some cases, these light areas had expanded centrifugally to occupy virtually the entire organelle (Figs. 3-5). We considered this organelle to be derived from melanosomes but because of the presence of different stages of what seemed to be melanin loss, we also considered the organelle to have lysosomal properties. We refer to these as Type 1 lysosomes. Fig. 6 shows the number and size distribution of these organelles in young and old monkeys. They tend to be in the middle third of the cell and they diminished with age. The size distribution covers a relatively narrow range compared to that of melanosomes. The average length of the long axis of 42 such organelles was 0.56 microns (SD =0.18).

Fig. 3.

Shows examples of Type 1 lysosomes (white arrows). They have a light area in an otherwise densely dark melanosome-like organelle. Other organelles seen are melanosomes (M), mitochondria (mi) and outer segment s (OS). The calibration at the lower left indicates 0.5 microns.

Fig. 5.

Shows four such melano-lysosomes revealing considerable loss of their dark melanin-like material. The calibration, lower left, indicates 0.1 microns.

Fig. 6.

Compares the length of the long axis (abscissa) and the number (ordinate) of these Type 1 lysosomes in the basal, middle and apical parts of the RPE cell of the 1, 6, 24 and 35 year old monkeys. The 1 year old monkey has many of these organelles.

3.3. Canonical lysosomes

Figs. 7 and 8 showa more typical lysosome, referred to as Type 2, in a 35-year-old monkey. These contain a light amorphous matrix material that usually incorporated multiple dark inclusion bodies considered to be melanosomes (Fig. 8). These same lysosomes were found in the 6-year- old monkey but with fewer Inclusions than those found in the RPE of the older monkey (Fig. 9). The one- yearold monkey had none of these lysosomes (Fig.10). The cytoplasm of the 1-year old monkey showed many melanosomes, including the Type 1 lysosome (Fig.11). The Type 2 lysosomes had a much greater range of sizes and more irregular perimeters than melanosomes and the Type 1 lysosome. The average length of 53 such Type 2 lysosomes was 1.43 microns (SD = 0.1). Evidence that Type 2 lysosomes were ingesting melanosomes is illustrated in Figs. 12 and 13. Here elongated and unequivocal melanin granules have been encased by this organelle. Evidence that such melanin-like inclusions are being degraded is shown in Fig. 14 in which a scale of 1 to 5 is used to point out virtually no degradation, grade 1, to almost complete degradation, grade 5. Although there is considerable overlap in the grading scheme, all stages of degradation were seen within the same retina at the same point in time. The observation of more inclusion bodies in the older than the younger monkey and the fact that all stages of degeneration were seen simultaneously suggest that Type 2 lysosomes are long-lived.

Fig. 7.

Shows a RPE cell of the 35 year old monkey containing large amounts of Type 2 lysosomes (L2), many not labeled. Most of these organelles have dark inclusion bodies. Two lacking inclusion bodies are marked by black arrows. At the lower right there is a complex of many such Type 2 lysosomes and melanosomes all contained in an amorphous matrix. Mitochondria (mi) are near the basal side and Bruch’s membrane (BM) is below. The calibration, lower right, indicates 1 micron.

Fig. 8.

Shows a Type 2 lysosome in the 35 year old monkey at higher magnification, revealing the many dark inclusion bodies they contain and their slightly irregular perimeters. The calibration, lower left, indicates 0.5 microns.

Fig. 9.

Shows Type 2 lysosomes in the RPE of the 6 year old monkey. The organelles have fewer dark inclusion bodies revealing more of the lighter matrix material and a more regular perimeter. The calibration, lower left, indicates 1 micron.

Fig. 10.

Compares the length of the long axis (abscissa) and the number (ordinate) of Type 2 lysosomes in the basal, middle and apical part of the RPE cell of the 1, 6, 24 and 35 year old monkeys. The 1 year old monkey has none of these organelles.

Fig. 11.

Shows that the cytoplasm of the RPE of the 1year old monkey contains many Type 1 (arrows) but none of the Type 2 lysosomes. The calibration, lower right indicates 0.7 microns.

Fig. 12.

Shows a large elliptical melanosome (lower L) encased by the amorphous matrix of a Type 2 lysosome. Another such lysosome without such a typical melanosome is also present in this section (upper L). The calibration, lower right, indicates 0.4 microns.

Fig. 13.

Shows another example of the engulfing of a typical elongated melanosome by a Type 2 lysosome (L). Another such lysosome (L) but without such a typical melanosome is seen above. The calibration indicates 0.4 microns.

Fig. 14.

Shows a group of Type 2 lysosomes graded for the amount of degradation of the melanosomes they contain. Grade 1 has virtually un-degraded melanosomes; the progressively higher grades show more melanosome degradation to Grade 5 where no large sized melanosomes remain. The calibration, lower left, indicates 0.6 microns.

Table 1 shows quantitative measurements of the melanosomes and lysosomes found in the macular RPE of all 6 monkeys. There is an obvious decrease in the number of melanosomes and Type 1 lysosomes but an increase in Type 2 lysosomes with age.

Table 1.

Organelles/micron2.

| Age (years) | Melanosomes | Type 1 Lysosomes | Type 2 Lysosomes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.21 | 0.31 | 0.0 |

| 6 | 0.08 | 0.02 | 0.12 |

| 24 | 0.11 | 0.01 | 0.31 |

| 24 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.24 |

| 26 | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.11 |

| 35 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 0.55 |

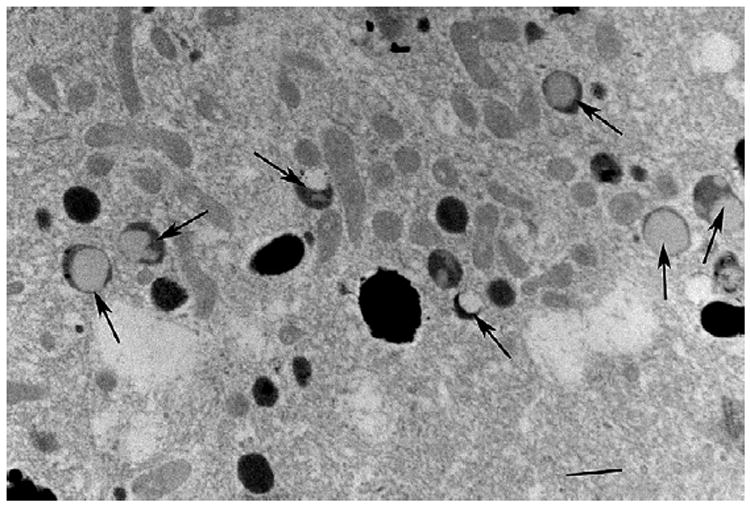

3.4. Phagosomes

Phagosomes were rare in the RPE of both young and old monkeys. Fig. 15 shows typical phagosomes in macular RPE. They were larger than the Type 2 lysosomes and were never found to be engulfed by these lysomes. But they were often found to be making membrane contacts with Type 2 lysosomes where degradation could occur. Fig. 16 shows several examples of phagosomes in close contact with Type 2 lysosomes. Some show evidence of degradation of the membranous sacs of outer segments, again suggesting that phagosomes may be degraded by such contacts. We encountered one example of a phagosome being near but not making close contact with a Type 1 lysosome (Fig. 17).

Fig. 15.

Shows two phagosomes (P) in close contact with Type 2 lysosomes (L). The calibration indicates 0.5 microns.

Fig. 16.

Shows three phagosomes (P) in the RPE of a 24 year old monkey, all in close contact with Type 2 lysosomes (L). There is more degradation of these phagosomes with distance from the apical side of the cell. The calibration, lower left, indicates 0.6 microns.

Fig. 17.

Shows a Type 1 lysosome (large black arrow) that is near but not in close contact with a phagosome (P). Melanosomes (small black arrows) and mitochondria are also seen. The calibration indicates 0.5 microns.

4. Discussion

This paper describes a unique organelle in the RPE that has not previously been singled out as being unique. The organelle has the size and shape of a small melanosome but is different in having an area lacking melanin. In some of these organelle this light, amelanotic area occupies virtually the entire organelle leaving only a thin, peripheral rim of residual melanin. It is reasonable to believe that this organelle is lysosomal and autophagic in dissolving its own melanin. Melanosomes are known to have lysosomal properties (Diment et al., 1995; Orlow, 1995; Kim and Choi, 1998; Schraemeyer et al., 1999). Feeney (1978) has reported that some melanosomes in human RPE have hydrolytic enzyme activity. Proving that this organelle has such properties will require immune-gold labeling of this organelle for lysomomal enzymes. Conversely, the organelle may be synthesizing melanin starting from the periphery of the organelle and progressing centripetally. This idea seems less likely because the synthesis of melanin starts with a non-melanin containing striated complex throughout the organelle, which gradually become pigmented with melanin (Wasmeier et al., 2008). In addition melanosome formation in RPE is completed before birth in mice (Lopes et al., 2007;Wasmeier et al., 2008) and perhaps also in man (Hogan et al., 1971). We have observed this same, novel organelle in murine RPE (unpublished observations). It is known that melanin is being lost from RPE with increasing age as determined histologically (Feeney-Burns et al., 1984) and biochemically (Schmidt and Peisch, 1986). Our results confirm this conclusion and indicate at least two routes through which this loss could occur. Either or both Type 1 and 2 lysosomes could be responsible. Why there are two routes and which is more responsible for the loss is difficult to conclude. The Type 1 lysosome is autophagic, involved in degrading its own melanin. Its transformation from melanosome to lysosome may be triggered by oxidative stress that causes some but not all melanosomes to change. From this perspective, the Type 1 lysosome represents a degenerative process because melanosomes, full of melanin, are beneficial to the RPE protecting against phototoxicity as well as oxidative stress (Sarna et al., 2003; Sarangarajan and Apte, 2005; Sundelin et al., 2001). Type 2 lysosomes appear to be heterophagic engulfing melanosomes and degrading phagosomes. The latter must involve much of their action because of the enormous turn-over of outer segments. It is interesting that although we observe the breakup of melanosomes they engulf, the Type 2 organelle seems to endure for a long time ever increasing its load of melanosomes. Perhaps Type 2 lysosomes may not as efficient as Type 1 lysosomes for degrading melanin.

The incomplete degradation of phagosomes is thought to be the main source of lipofuscin and the increasing auto-fluorescence of aging human RPE (Weiter et al., 1986). An age-related increase in auto- fluorescence also occurs in rhesus monkeys (Gouras et al., 2008b). In human retina, Feeney (1978) described lipofuscin containing organelles without melanosomes, which were considered the cause of much of the auto-fluorescence. But lipofuscin was also detected in lysosomes, which contained melanin and these organelles must also contribute to auto-fluorescence in aging human RPE. Fluorescent melano-lysosomes have also been reported in cultured RPE (Burke and Skumatz, 1998). In monkey Type 2 lysosomes were by far the main organelle that built up with age; pure lysosomes without melanin were rare. We therefore assume that Type 2 lysosomes also contain fluorescent lipofuscin although we could not identify lipofuscin by ultra-structural criteria. Type 2 lysosomes contain two distinguishing structures. One is an amorphous material that comprises the lysosome and the other involves the numerous melanin bodies embedded within this material. It is reasonable to assume that the fluorescent lipofuscin resides in the amorphous material and not in the melanosomes. Why virtually all Type 2 lysosomes which accumulate in aging monkey RPE contain melanosomes whereas in humans pure lysosomes without melanin are more common is intriguing.

Phagosomes appear to be degraded by Type 2 lysosomes but not in the same way as melanosomes. Melanosomes are engulfed by the lysosomal matrix and then broken down, apparently incompletely. Phagosomes were not engulfed but made close contact with Type 2 lysosomes. This pattern has also been reported in rat (Bosch et al., 1993). They suggested that lysosomes interacted with phagosomes by pore or bridge-like structures where interchange of contents could take place. Perhaps this also occurs in monkey RPE. Macrophages in the post-partum involuting uterus also degrade phagocytized material by contacts between phagosomes and lysosomes (Brandes and Anton, 1969). Whatever the mechanism of phagosome degradation is, it must be rapid because phagosomes were seldom seen in either young or old RPE. Recent measurements of phagosome degradation in mice indicate that it is virtually complete within hours (Damek-Poprawa et al., 2009). The absence of structural remnants of phagosomes implies that the material they contain, which is destined to give rise to lipofuscin, exists at the molecular rather than the organelle level.

The accumulation of melano-lysosomes in the RPE parallels the development of the maculopathy in monkeys but occurs at a much earlier age (Gouras et al., 2008b, 2010) than in humans (Feeney, 1978). If we assume that outer segment turn-over in monkeys is not faster than it is in humans, then the age related buildup of Type 2lysosomes must not be due solely to the integrated load of phagosomes but to another age-dependent factor that influences this buildup, a feature of aging in many other organs (Yin, 1996). This factor that occurs earlier in the life of the monkey would seem to be related to its shorter lifespan and faster rate of senescence. This faster rate could be related to a greater vulnerability to oxidative stress, which may be driving the maculopathy more than the accumulation of lipofuscin.

Fig. 4.

Shows a more magnified view of Type 1 lysosomes, several of which have lost virtually all their dark core with only a peripheral rim left. The calibration, middle- left, indicates 0.5 microns.

Acknowledgments

We were supported by NEI grants EY015293 and RR00163, the Foundation Fighting Blindness and Research to Prevent Blindness Inc.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None to declare.

References

- Bergmann M, Schutt F, Holz FG, Kopitz J. Inhibition of the ATP driven proton pump in RPE lysosomes by the major lipofuscin fluorophore A2-E may contribute to the pathogenesis of age-related macular degeneration. FASEB J. 2004;18:562–564. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-0289fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosch E, Horwitz J, Bok D. Phagocytosis of outer segments by retinal pigment epithelium: phagosome–lysosome interaction. J Histochem Cytochem. 1993;41:253–263. doi: 10.1177/41.2.8419462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandes D, Anton E. Lysosomes in uterine involution: intracytoplasmic degradation of myofilaments and collagen. J Gerontol. 1969;24:55–69. doi: 10.1093/geronj/24.1.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke JM, Skumatz MB. Autofluorescent inclusions in long term postconfluent cultures of retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39:1478–1486. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damek-Poprawa M, Diemer T, Vanda S, Lopes VS, Lillo C, Harper DC, Marks MS, Wu Y, Sparrow JR, Rachel RA, Williams DS, Boesze-Battaglia K. Melanoregulin (MREG) modulates lysosome function in pigment epithelial cells. J Cell Biol. 2009;284:10877–10889. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808857200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diment S, Eidelman M, Rodriguez GM, Orlow SJ. Lysosomal hydrolases are present in melanosomes and are elevated in melanizing cells. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:4213–4215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.9.4213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney L. Lipofuscin and melanin of human retinal pigment epithelium. Fluorescence, enzyme cytochemicaland ultrastructural studies. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1978;17:583–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feeney-Burns L, Hilderbrand ES, Eldridge S. Aging human RPE: morphometric analysis of macular, equatorial, and peripheral cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1984;25:195–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finnemann SC, Leung LW, Rodriguez-Boulan E. The lipofuscin component A2E selectively inhibits phagolysosomal degradation of photoreceptor phospholipid by the retinal pigment epithelium. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:3842–3847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.052025899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouras P, Ivert L, Landauer N, Neuringer M, Mattison J, Ingram DK. Drusenoid maculopathy in rhesus monkeys: effects of age and gender. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008a;246:1395–1402. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-0910-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouras P, Ivert L, Mattison J, Ingram DK, Neuringer M. Drusenoid maculopathy in rhesus monkeys: autofluorescence, lipofuscin and drusen pathogenesis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2008b;246:1403–1411. doi: 10.1007/s00417-008-0911-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouras P, Ivert L, Neuringer M, Mattison JA. Topographic and age-related changes of the retinal epithelium and Bruch’s membrane of rhesus monkeys. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2010;248:973–984. doi: 10.1007/s00417-010-1325-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan MJ, Alvarado JA, Weddell JE. Histology of the Human Eye. W.B. Saunders Company; Philadelphia, PA: 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Kim IT, Choi JB. Melanosomes of retinal pigment epithelium, distribution, shape, and acid phosphatase activity. Kor J Ophthalmol. 1998;12:85–91. doi: 10.3341/kjo.1998.12.2.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopes VS, Wasmeier C, Seabra MC, Futter CE. Melanosome maturation defect in Rab38-deficient retinal pigment epithelium results in instability of immature melanosomes during transient melanogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18(10):3914–3927. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-03-0268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlow SJ. Melanosomes are specialized members of the lysosomal lineage of organelles. J Invest Dermatol. 1995;105:3–7. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12312291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radu RA, Mata NL, Bagla A, Travis GH. Light exposure stimulates formation of A2E oxiranes in a mouse model of Stargardt’s macular degeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:5928–5933. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308302101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarangarajan R, Apte SP. Review: melanization and phagocytosis: implications for age-related macular degeneration. Mol Vis. 2005;11:482–490. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarna T, Burke JM, Korytowski W, Rózanowska M, Skumatz CM, Zareba A, Zareba M. Loss of melanin from human RPE with aging: possible role of melanin photooxidation. Exp Eye Res. 2003;76(1):89–98. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4835(02)00247-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt SY, Peisch RD. Melanin concentration in normal human retinal pigment epithelium. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986;27:1063–1067. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schraemeyer U, Peter S, Thumann G, Kociok N, Heiman K. Melanin granules of retinal pigment epithelium are connected with the lysosomal degradation pathway. Exp Eye Res. 1999;68:237–245. doi: 10.1006/exer.1998.0596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutt F, Davies S, Kopitz J, Holz FG, Boulton ME. Photodamage to human RPE cells by A2-E, a retinoid component of lipofuscin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41:2303–2308. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schutt F, Bergmann M, Kopitz J, Holz FG. Mechanism of the inhibition of lysosomal functions in the retinal pigment epithelium by lipofuscin retinoid component A2-E. Ophthalmology. 2001;98:721–724. doi: 10.1007/s003470170078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparrow JR, Boulton M. RPE lipofuscin and its role in retinal pathobiology. Exp Eye Res. 2005;80:595–606. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2005.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss O. The retinal epithelium in visual function. Physiol Rev. 2005;85:845–881. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00021.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundelin SP, Nilsson SE, Brunk UT. Lipofuscin-formation in cultured retinal pigment epithelial cells is related to their melanin content. Free Rad Biol Med. 2001;30:74–81. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5849(00)00444-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wasmeier C, Hume AN, Bolasco G, Seabra MC. Melanosomes at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2008;121:3995–3999. doi: 10.1242/jcs.040667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiter JJ, Delori FC, Wing GL, Fitch KA. Retinal pigment epithelial lipofuscin and melanin and choroidal melanin in human eyes. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986;27:145–152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin D. Biochemical basis of lipofuscin, ceroid, and age pigment-like fluorophores. Free RadicBiol Med. 1996;21:871–888. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(96)00175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]