Abstract

Objective:

Recent evidence suggests that early or induced menopause increases the risk for cognitive impairment and dementia. Given the potential for different cognitive outcomes due to menopause types, it is important that present research on menopause and cognition distinguishes between types. The aim of this project was to determine to what extent research looking at cognition in postmenopausal women published in one year, 2016, accounted for menopausal type.

Methods:

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and PsychINFO using keywords and MeSH terms for menopause and cognition. We included any research paper reporting a cognitive outcome measure in a menopausal human population. Differentiation between the types of menopause was defined by four categories: undifferentiated, demographic differentiation (menopause type reported but not analyzed), partial differentiation (some but not all types analyzed), and full differentiation (menopause types factored into analysis, or recruitment of only one type).

Results:

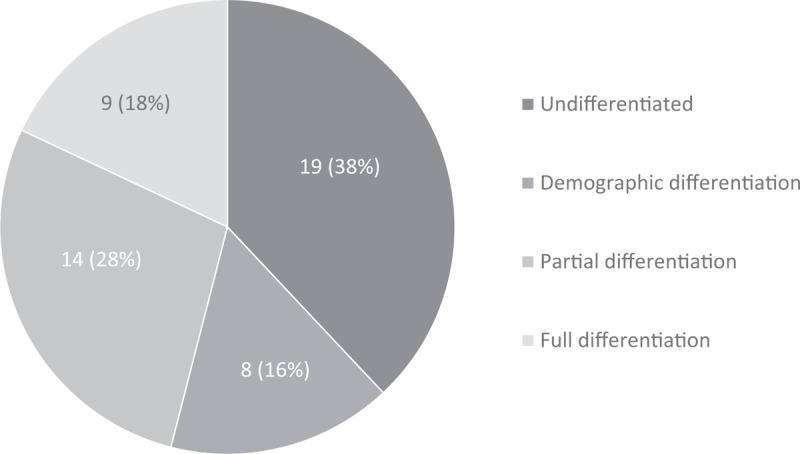

Fifty research articles were found and analyzed. Differentiation was distributed as follows: undifferentiated, 38% (19 articles); demographic differentiation, 16% (8); partial differentiation, 28% (14); and full differentiation, 18% (9).

Conclusions:

This review revealed that although some clinical studies differentiated between the many menopauses, most did not. This may limit their relevance to clinical practice. We found that when menopause types are distinguished, the differing cognitive outcomes of each type are clarified, yielding the strongest evidence, which in turn will be able to inform best clinical practice for treating all women.

Keywords: Cognitive decline/cognitive aging, Early menopause, Menopause, Menopausal transition, Premature ovarian failure, Surgical menopause

Menopause is defined as the reproductive condition after 12 consecutive months of amenorrhea.1 For a majority of women, menopause occurs at an average age of 51 years, as a result of the complex hormonal changes that accompany the reduction in ovarian follicles.2 Along with a drop in circulating hormone levels, menopause is often associated with the experience of hot flashes, night sweats, sleep problems, mood changes, and vaginal dryness.3 Despite similar symptoms and the common name of menopause, there is, however, no single pathway to the end of menses. In fact, menstruation ceases for different reasons, in different ways, at different time points in the lifespan, with different health risks.

For a small but significant number of women, menopause occurs earlier than the normative age range.4,5 Included in this spectrum of menopauses is premature (younger than 40 y), early (between 40 and 45 y), and induced (oophorectomy with or without hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy [BSO], the removal of ovaries and fallopian tubes, or ovarian ablation through radiation6). These different menopause types have distinct hormonal changes both leading up to and after the cessation of menses, potentially leading to different health trajectories. Although not considered an induced menopause, hysterectomy with ovarian sparing has been shown to result in decreased ovarian function.7,8 Thus, using menopause as a blanket word to describe any “cessation of menses” erases these differences in the physiology, etiology, and health outcomes of the many menopauses.

Longitudinal studies of women entering nonsurgical menopause of any type (spontaneous, early, or premature) not on hormone therapy (HT) have shown small decreases in verbal fluency, verbal and episodic memory, attention, and executive function.9-11 When adjusting for age and other menopause-related factors such as symptoms, body-mass index (BMI), 17β-estradiol (E2) levels, and general health, these cognitive differences, however, have not been replicated.12

On the contrary, significant cognitive decline is seen when comparing cognition before and after surgery in younger women with induced menopause, particularly in the areas of verbal memory and global cognition.13-15 Risk of cognitive impairment is increased for women who undergo induced menopause before age 49 compared with referent women, with risk increasing with younger age at surgery.16,17 The earlier the age of induced menopause, the steeper the cognitive decline, particularly in episodic and semantic memory.14 As well, higher levels of Alzheimer's disease (AD) biomarkers are associated with younger age at surgery.14 Women undergoing menopause before age 40, regardless of type (induced or POI), have poorer verbal and visual memory compared with women with spontaneous menopause.18 Given these differing cognitive outcomes, research in menopause and cognition needs to consider the different types of menopause in its design and analysis.

To determine whether or not more recent cognitive literature accounts for the type of menopause in its design and analysis, we reviewed the literature on menopause and cognition in one year, 2016. We then classified the relevant articles and quantified the proportion in each differentiation category. The study design, population, and cognitive results were extracted for each article to gain further information on the studies within each category. In this way, we developed a typology of papers dealing with cognition and menopause based on the type of menopause differentiation. Although this typology is not quantitative, it is also not solely descriptive because there is consideration in each category of how much and how closely the types of menopause are considered. We decided on this approach so readers can make their own judgments regarding the contribution of each study and the reliability of their respective outcomes. Finally, we provide recommendations for future human research on cognition in menopausal populations. Described below is an overview of the distinct menopausal etiologies and associated symptomatology that we used to develop a typology of menopause differentiation.

The many menopauses

Spontaneous menopause

Spontaneous menopause (often referred to as “natural menopause”) is diagnosed retrospectively after a year has elapsed since a woman's last menstrual period (LMP). The majority of women experience menopause between 45 and 55 years of age.19 Before the cessation of menses, women enter the menopausal transition (perimenopause); cycle lengths become variable as hormone levels begin to fluctuate and gradually fall.20 With fewer follicles maturing in the aging ovaries, levels of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) become elevated due to disinhibition, although 17β-estradiol (E2) levels become highly variable. On average, the perimenopausal period lasts about 4 years.1,21 After the LMP, both E2 and progesterone remain circulating at very low levels (2-35 pg/mL and 0-0.8 ng/mL, respectively), although high FSH levels stabilize.1,22 Postmenopausal women also produce low but stable quantities of androgens such as testosterone, dihydrotestosterone (DHT), dehydroandrosterone (DHA), and dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHAS).22 In most postmenopausal women, reduction in ovarian hormones is associated with the emergence of physiological symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats, sleep problems, mood changes, and vaginal dryness.23

Premature and early menopauses

Nonsurgical mid-life cessation of menses can occur outside of the expected age range. Entering menopause before age 45 is considered “early,” whereas entering menopause before age 40 is designated as “premature” and is termed Primary Ovarian Insufficiency (POI). The prevalence of these two types is estimated at about 5% and 1% to 2%, respectively.24,25 Progress of early menopause typically follows the same stages as spontaneous menopause.1 A diagnosis of POI, however, requires two occasions of amenorrhea for over 4 months, accompanied by documented elevation in circulating gonadotrophins (serum FSH concentration >40 IU/L), reduced circulating androgens, and low E2 levels.3,26,27 In addition, the decline in ovarian function in POI does not compare with spontaneous menopause, as hormone levels can be extremely variable and some women have reported spontaneous return of menses or even pregnancy.28 There is also an inconsistent and varied symptom experience for women with POI, with additional symptoms like hair loss, dry eyes, cold intolerance, joint clicking, and hypothyroidism.29

POI and early menopause are often linked to underlying factors beyond gonadal hormone levels. Cigarette smoking, high body mass index, and low socioeconomic status have all been associated with POI and early menopause.30,31 POI has been linked with genetic abnormalities, metabolic or autoimmune disorders, infections, and enzyme deficiencies, though it is often idiopathic.28 Recent research also suggests that women with POI do not report a reduction in menopausal symptoms with aging.29

Notably, ovary-sparing hysterectomy can reduce the age of menopause by an average of 4 years through compromise of ovarian function, related to age at surgery.7,32 A prominent hypotheses for ovarian cessation after uterine removal is that the surgery affects blood flow to the ovaries,8,33 but evidence for this is mixed. Other possible causes are that the uterus itself regulates pituitary FSH secretion and thus affects follicle development.7,8 It may also be that the condition that led to hysterectomy increases the risk for ovarian failure. Thus, depending on the timing of surgery, gradual ovarian cessation before age 45 due to hysterectomy might be considered noninduced, early menopause.

Induced menopause

Induced menopause refers to the permanent cessation of menses due to the removal of the ovaries, either surgically (removal of the ovaries and the fallopian tubes [BSO], or of just the ovaries), or ovary ablation via chemotherapy or radiation.34 Removal or ablation of the ovaries through any of these procedures is most often carried out for either the treatment of benign ovarian disorders such as cysts, abscesses, endometriosis, ovarian torsion, or as a preventive measure against breast and ovarian cancer.35

In contrast to spontaneous, early, or premature naturally occurring menopause, endocrine change after oophorectomy or chemotherapy is characterized by an abrupt and total loss of ovarian function. Circulating levels of estrogens and progesterone drop significantly within 24 hours of surgery, whereas levels of FSH and LH surge.36,37 Furthermore, women with BSO have a 25% decrease in circulating testosterone levels compared with spontaneously menopausal women.38 A large proportion of women with induced menopause report more severe symptom experiences compared with those of women with spontaneous menopause.39 Ovarian removal or ablation is also accompanied by an abrupt onset of symptoms, paralleling abrupt hormonal changes.39 Symptoms related to induced menopause include rapid onset of hot flashes, vulvovaginal atrophy, mood changes, sleep disturbance, headaches, joint pain, dyspaneuria, and sexual problems.36,40-43

It is important to note that the term surgical or induced menopause is sometimes used to refer to hysterectomy and/or oophorectomy. Ovarian failure after hysterectomy, however, involves gradual changes that take place over many years, unlike the abrupt change associated with induced menopause.14,44 Although hysterectomy with ovarian sparing may lead to early menopause in some cases,32 the surgery itself does not induce menopause and thus should not be termed induced or surgical menopause.

METHODS

This research was conducted according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. To identify studies in postmenopausal women involving cognition, we searched MEDLINE, PsychINFO, and Embase. We used both MeSH terms and keywords to cast the widest net for menopause and cognition studies, and hand-sorted by inclusion/exclusion criteria later. The term menopause was defined to include perimenopause and postmenopause as associated terms, combined with the Boolean “OR.” The search terms for cognition were determined by scrutinizing the full MeSH tree and selecting those pertaining to memory, cognition, and learning. The chosen terms of cognition, executive function, learning, memory, language, and problem solving were then reiterated as keywords, using appropriate Boolean syntax. Cognition terms were searched in conjunction with menopause terms using a Boolean “AND.” A search limit was applied to remove studies in nonhuman animals, reviews, and those not in English. Year limits were then applied to return papers released between January 1, 2016 and January 25, 2017 (including any online publication ahead of print).

Inclusion criteria were as follows: study conducted in humans, includes postmenopausal women, and at least one cognitive outcome measure.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: editorial or review, society guidelines or position statement, assessment or methodological tool, textbook chapter, non-English paper, publications before January 2016 and after January 2017. Articles were assessed by two researchers for inclusion by title and abstract, and then, for those included, the full text assessed by four.

Defining menopausal typology

To classify menopausal types, we looked for explicit mention of spontaneous or surgical menopause, POI, or descriptive information such as years since menopause or age of LMP. Working with these parameters, a typology was developed to classify the extent to which a study differentiated menopausal types.

When a study considered menopausal type—through reporting, study design, and/or analysis—we called this “differentiation.” Four categories were used to classify differentiation further: undifferentiated, demographic differentiation, partial differentiation, or full differentiation (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Definitions of the four categories used to classify menopausal type differentiation in recent papers looking at cognition and menopause

| Differentiation type | Definition |

| Undifferentiated | No information regarding participants’ menopausal type or age at menopause. |

| Demographic differentiation | Time since LMP or number of participants in each menopausal type reported but not factored into analysis. |

| Partial differentiation | Reports on and factors into analysis either age of LMP and/or years since menopause and/or type of menopause but not all three. |

| Full differentiation | Reports on and factors into analysis age of LMP, years since menopause, and type of menopause or limits its investigation to only one menopausal type. |

-

1.

“Undifferentiated” refers to a study that provides no information on menopausal type or time since menopause (TSM).

-

2.

“Demographic differentiation” refers to a study that provides some descriptive information regarding the menopausal type, either through reporting mean age at menopause, TSM, or percentage of participants from each menopausal type, but it does not consider these in analysis.

-

3.

“Partial differentiation” refers to a study that provides partial information of the different menopausal types either including type of menopause, age at menopause, or TSM and accounting for some of those in the analysis. For example, an article that considers the age at menopause and uses it in the analysis but not the type of early menopause (POI or induced) would be classified as partial differentiation.

-

4.

“Full differentiation” refers to a study that reports on the different menopausal types and includes those in the analysis, or includes only one menopausal type.

To ensure consistency and reliability of the coding, four people coded all eligible references independently. The four coders discussed any discrepancies to reach a consensus decision before placing a paper in one of the four categories.

RESULTS

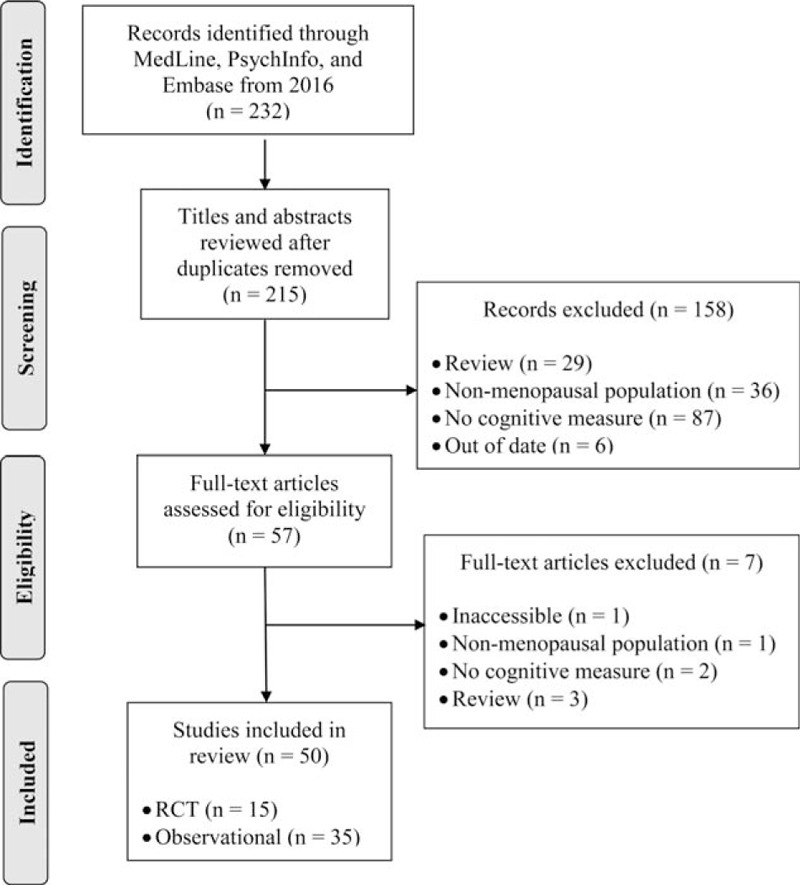

Our search yielded 232 potentially relevant articles—175 from MedLine, 46 from PsychInfo, and 11 from Embase. After removing duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 215 articles were screened. One hundred fifty-eight articles were removed based on our screening criteria. The remaining 57 articles were read in full to determine eligibility and classification; 7 articles did not meet inclusion criteria or were inaccessible. This left 50 articles for review: 35 observational studies and 15 randomized control trials (RCTs) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process.

Typology classification

-

1.

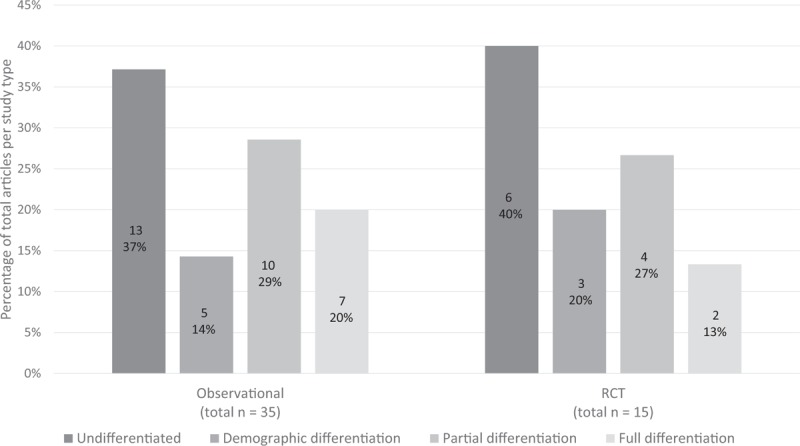

Undifferentiated: Thirty-eight percent (19) were classified as undifferentiated (Fig. 2). None of these studies described the age of or reason for menopause. These included both observational studies (13) and RCTs (6) (Fig. 3). These studies did not provide details on menopausal types or TSM but four studies noted whether women were in pre-, peri-, or postmenopause either by self-report or FSH level (Table 2).

-

2.

Demographic differentiation: Sixteen percent (8) were classified as demographic differentiation (Fig. 2). These included 5 observational studies and 3 RCTs (Fig. 3). In these studies, the type of menopause was reported as characteristics of the population, but these characteristics were not included in the analysis. In this category, when reported, information on TSM, age at menopause, or proportion of induced menopausal participants for each study can be found in the column labeled “Age range, menopausal definition and assessment” (Table 3).

-

3.

Partial differentiation: Twenty-eight percent (14) of the total articles had partial differentiation (Fig. 2). These included 10 observational studies and 4 RCTs. Within these 14 articles, 6 studies excluded women with induced menopause (both oophorectomy and/or hysterectomy), but included women who went into menopause at both younger and older ages, leaving unclear whether women with early menopause or POI were also included.70-75 Five other studies included women's age at menopause or years since menopause as factors in analysis, but gave no descriptive data about or cause of menopause.76-80 The remaining 3 articles compared cognitive outcomes of surgical and natural menopause, but did not report or disaggregate the data by the age of menopause for either group.81-83 When reported, information on TSM, age at menopause, or proportion of induced menopausal participants for each study can be found in the column labeled, “Age range, menopausal definition and assessment” (Table 4).

-

4.

Full differentiation: Eighteen percent (9 articles) had full differentiation (Fig. 2). These included 7 observational studies and 2 RCTs (Fig. 3). In this category, when reported, information on TSM, age at menopause, or proportion of induced menopausal participants for each study can be found in the column labeled, “Age range, menopausal definition and assessment” (Table 5). We describe these studies in more detail to elucidate the ways in which menopausal types can be fully differentiated.

FIG. 2.

Differentiation classification in cognition and menopause literature of 2016; labels indicate number of articles per category (percentage of total articles).

FIG. 3.

Proportion of differentiation types in observational studies and randomized control trials (RCT).

TABLE 2.

Undifferentiated articles (main cognitive and brain outcomes only)

| Citation | Study | Age range, menopausal definition and assessment | Cognitive and brain assessment | Main cognitive and brain outcomes | Category explanation |

| Alwerdt J et al. Menopause. 2016 Aug;23(8):911-918. | • n = 200 • National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey• Urinary phytoestrogen (isoflavone and lignan) | • Range = 65-85 y • Menopause undefined | • Digit Symbol Substitution Test | Significant relationship between processing speed and phytoestrogen levels. | No information on TofM, TSM, or AatM |

| Berent-Spillson A, et al. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2017 Feb;76:218-225 | • n = 54 • Blood E2 and FSH • Functional neuroimaging | • Range = 42-61 y • Premenopause (regular menstrual cycles and FSH <11 IU/L) • Perimenopause (at least one cycle in the previous year and FSH between 11 and 45 IU/L) • Post menopause (no cycles in previous year and FSH >40 IU/L). | • Exposure to emotional images | BehavioralNone.Neuroimaging All: increased activation of prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate, temporal parietal-occipital junction, and hippocampus post> peri>pre. | While menopause stage defined, no information on TofM, TSM, or AatM. |

| Bojar I, et al. Arch Med Sci. 2016a Dec 1;12(6):1247-1255. | • n = 402 • Blood FSH and CRP • APOE status | • Range = 50-65 y • 2+ y since LMP • FSH > 30 mIU/mL | • Continuous Performance Test • Finger Tapping Test • Shifting Attention Test • Stroop Test • Symbol Digit Modalities • Verbal Memory Test | APOE status: significant effect on neurocognitive index: APOE e2/e3> e3/e3> ε4 Higher CRP: lower neurocognitive index APOE by CRP interaction. | No information on TofM, TSM, or AatM |

| Bojar I, et al. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2016b;42(3-4):169-185 | • n = 402 • Blood FSH • APOE status | • Range = 50-65 y • 2+ y since LMP • FSH > 30 mIU/mL | Ibid. | ε4 APOE: correlated with worse neurocognitive index. | No information on TofM, TSM, or AatM |

| Campbell KL, et al. Psychooncology. 2018 Jan;27(1):53-60. | • n = 14 (n = 7 intervention) • Breast cancer survivors • 150 min/wk of moderate to-vigorous aerobic exercise • Tested 3 mo before and after exercise | • Range = 40-65 y • Menopause either spontaneous or chemotherapy-induced • Menopause undefined | Objective• Controlled Oral Word Association Test • HVLT • Revised Trail Making Test • Stroop • Verbal fluency Subjective • Quality of Life questionnaires | Objective Aerobic exercise: significantly improved processing speed compared to usual-lifestyle controls. Subjective None | No information on TofM, TSM or AatM. |

| Chae JW, et al. PloS One. 2016 Oct 4;11(10):e0164204. | • n = 125 • Early-stage breast cancer patients in chemotherapy • Blood Tumor Necrosis Factor-α and Interleukin-6 and SNPs | • Mean = 50.3 y (no range) • 52% pre-menopausal before treatment • Menopause undefined | Objective • Headminder Subjective • Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - Cognition scale (FACT-Cog) | Objective None Subjective Significant relationship between perceived cognitive impairment, anxiety/insomnia, and interleukin-6. | No information on TofM, TSM, or AatM. |

| Ganz PA, et al. Lancet. 2016 Feb 27;387(10021):857-865. | • n = 1,193 (n = 601 tamoxifen, n = 592 anastrozole) • Hormone-positive breast cancer patients treated with lumpectomy and whole-breast irradiation • Testing session every 6 mo for 6 y | • <60 y and ≥60 y (no means or range) • Menopause undefined | • Breast Cancer Prevention Trial Symptom Checklist (subjective cognitive function) • The 12-Item Short Form Health Survey | Tamoxifen or anastrozole: no significant correlation with mental health or cognition. | No information on TofM, TSM, or AatM |

| Geller EJ, et al. Female Pelvic Med Reconstr Surg. 2017 Mar/Apr;23(2):118-123. | • n = 45 (n = 21 tropsium chloride) • Diagnosed with over-active bladder • Tested at baseline, 1 wk, and 4 wk after tropsium chloride | • Mean = 68 y (no range) • Unclear whether all participants had entered menopause. | • Digit Span • Epworth Sleepiness Scale • HVLT-Revised • Mini Mental Status X • Trail Making Test A and B | HVLT-Revised decreased with increased age (independent of treatment) | No information on TofM, TSM, or AatM. |

| Haring B, et al. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2016 Jun;116(6):921-930.e1. | • n = 6,425 • Women's Health Initiative Study • Median follow-up of 9.11 y • Dietary patterns determined via multiple scales | • Range = 65-79 y • Menopause undefined | • Diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment or probable dementia from medical history | No significant relationship found between dietary patterns and development of mild cognitive impairment or probable dementia. | No information on TofM, TSM, or AatM. |

| Katainen RE, et al. Maturitas. 2016 Apr;86:17-24. | • n = 3,189 (n = 1,666 with one or more chronic somatic disease) • Medical history questionnaire | • Range = 41-54 y • Pre-menopausal and early post-menopausal • Menopause undefined • Five age groups for analysis: 41-42, 45-46, 49-50, 51-52, and 53-54 y | • Women's Health Questionnaire (subjective cognitive symptoms) | Chronic somatic diseases correlated positively with climacteric symptoms. Cognitive difficulties associated with cardiovascular, sensory organ, musculoskeletal, gastrointestinal, and dermatological diseases. | No information on TofM, TSM, or AatM. |

| Kerschbaum HH, et al. J Neurosci Res. 2017 Jan 2;95(1-2):251-259. | • n = 253 men and women (n = 56 postmenopausal) • Salivary E2 and progesterone | • Range = 18-82 y (postmenopause 54-82 y) • Menopause undefined | • List-Method Directed Forgetting paradigm | Postmenopausal: enhanced retention in forget-cued compared to remember-cued. Salivary E2 levels correlated with item recall in remember-cued. | No information on TofM, TSM, or AatM. |

| Kirchheiner K, et al. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2016 Apr 1;94(5):1088-1098. | • n = 744 • European study on MRi-guided BRachytherapy in locally Advanced CErvical cancer • Diagnosed with locally advanced cervical cancer • In chemoradiation • Multiple testing sessions over 4 y | • Range = 40-58 y • Menopause undefined | • Quality of Life questionnaire (subjective cognitive function) | Chemoradiation: Cognition subscale ratings reduced for 4 y General quality of life improved after 6 mo and at every follow-up. | No information on TofM, TSM or AatM. |

| Koleck TA, et al. SpringerPlus. 2016;5. 422. | • n = 219 (n = 138 with breast cancer) • On adjuvant therapy • Oxidative stress and DNA repair gene polymorphisms | • Mean = 58.7 y (not greater than 75 y; no range) • Menopause undefined | • Delis Kaplan Executive Function System Color-Word Interference • Digit Symbol Substitution • Digit Vigilance • Grooved Pegboard • Paired Associates Learning • Rapid Visual Information Processing • Rey Auditory Verbal Learning -Verbal Fluency • Rey Complex Figure • Rivermead Story • Spatial Working Memory • Stockings of Cambridge | One or more oxidative stress and DNA repair gene polymorphisms: association of cognitive function composite Breast cancer survivors: cognitive function positively correlated with greater number of protective polymorphisms. | No information on TofM, TSM, or AatM. |

| Koleck TA, et al. Cancer Med. 2017 Feb;6(2):339-348. | • n = 329 • Diagnosed with Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2) early-stage breast cancer | • Range = 45-75 y • Menopausal before treatment • Menopause undefined | Ibid. | HER2-positive tumor diagnosis: significantly correlated with poorer verbal and visual working memory compared to HER2-negative. In women with multifocal or centric tumor: poorer verbal memory compared to a single focus tumor. | No information on TofM, TSM, or AatM. |

| Labad J, et al. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016 Oct;26(10):1683-1689. | • n = 65 (n = 36 on raloxifene) • Diagnosed with schizophrenia, • On antipsychotic medication • Tested multiple times out to 24 wk • SNP analysis | • Mean = 62 y (no range) • 1+ y since LMP • FSH <20 IU/L | • The Positive and Negative Symptom Scale (includes cognitive symptoms) | Homozygous for C allele of Estrogen Receptor 1 gene: correlated with neuropsychopathological improvement. | No information on TofM, TSM, or AatM. |

| Patel SK, et al. Clin Neuropsychol. 2017 Nov;31(8):1375-1386. | • n = 53 (n = 26 with newly diagnosed with breast cancer) • Comparing validity of computer-based versus paper-and-pencil tests | • Mean = 63 y (no range) • Menopause undefined | CogState digital tests: • Detection • Identification • One back and One Card Learning tasks Analog tests: • Functional Activities Questionnaire • HVLT • Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale | Limited convergent validity between analog and digital tests. | No information on TofM, TSM or AatM. |

| Prehn K, et al. Cortex. 2017 Mar 1;27(3):1765-1778. | • n = 37 obese women (n = 18 on caloric restriction) • Tested multiple times out to 4 wks • Structural and functional neuroimaging | • Mean = 61 y (no range) • Menopause undefined | • Auditory Verbal Learning Test • Digit Span • Stroop Test • Trail Making Test • Verbal Fluency | Caloric restriction; improved recognition memory and increased gray matter volume in the inferior frontal gyrus and hippocampus. Improved resting-state connectivity of parietal regions No significant differences after 4 wk of weight maintenance | No information on TofM, TSM, or AatM. |

| Strike SC, et al. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2016 Feb;71(2):236-242. | • n = 27 (n = 15 on multinutrient supplement) • Tested before and after treatment | • Range = 60-82 y • Menopause undefined | • Motor Screening Task • Paired Associate Learning • Stockings of Cambridge • Verbal Recognition Memory Task | 6 mo of multinutrient treatment: more words remembered and shorter mean latencies compared to placebo. | No information on TofM, TSM, or AatM. |

| Zhang T, et al. PloS One. 2016 Mar 14;11(3):e0150834. | • n = 1,365 (n = 254 CEE alone, n = 420 on CEE and progesterone) • Women's Health Initiative Memory Study - MRI • Tested yearly for an average of 8 y • Structural neuroimaging | • 65+ y (no range) • Menopause undefined | • Voxel based morphometry | HT: grey matter losses in anterior cingulate gyrus, medial frontal gyrus, and orbitofrontal cortex compared to placebo. | No information on TofM, TSM, or AatM. |

AatM, age at menopause; APOE, Apolipoprotein E; CEE, conjugated equine estrogens; CRP, C-reactive protein; E2, 17β-estradiol; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; HT, hormone therapy; HVLT, Hopkins Verbal Learning Test; LMP, last menstrual period; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphisms; TofM, types of menopause; TSM, time since menopause.

TABLE 3.

Articles with demographic differentiation (main cognitive and brain outcomes only)

| Citation | Study | Age range, menopausal definition, and assessment | Cognitive and brain assessment | Main cognitive and brain outcomes | Category explanation |

| Berndt U, et al. Breast Care. 2016 Aug;11(4):240-246. | • n = 92 • In treatment for breast cancer • 4 groups: tamoxifen only (n = 22), AI only (n = 22), switch from tamoxifen to AI (n = 15), or local therapy controls (n = 21) | • Mean = 65 y (no range) • Menopause undefined • TSM: Average 15 y since LMP | • Complex Figure Test • Mental Rotation Test • Object in Location Test • Trail Making Test A and B • Virtual Pointing Task • Wechsler Memory Scale | AI-only: worse general memory than other therapies. | No information on TofM, TSM reported but not analyzed, no information on AatM. |

| Braden BB, et al. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2017 May;24(3):227-246. | • n = 143 men and women (n = 94 women) • Three groups of HT: current (n = 32), past (n = 41), never (n = 21) • Structural neuroimaging | • Range = 49-91 y • 1+ y since LMP • TSM: Range of 3 to 46 y since LMP | • Auditory Verbal Learning Test • CVLT | HT users: better delayed verbal memory than never-users. Never users: Hippocampal size predicted memory performance. | No information on TofM; assessed if TSM differed across HT groups, but not for cognitive measures; no information on AatM. |

| Evans HM, et al. Nutrients. 2017 Jan 3;9(1):pii: E27 | • n = 72 (n = 37 on phytoestrogen resveratrol) • Tested at baseline and after resveratrol (14 wk) | • Range = 45-85 y • 6+ mo since LMP • TSM: Average 11 y since LMP | • Cambridge Semantic Memory Battery • Double Span Task • Modified MMSE • Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test • Trail Making Task | Resveratrol: better verbal memory and overall cognitive performance compared to placebo. | No information on TofM, average TSM reported but not analyzed, no information on AatM. |

| Kantarci K, et al. Neurology. 2016 Aug 30;87(9):887-896. | • n = 95 • Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study • Randomized to oral CEE (n = 29), E2 patch (n = 30), or placebo pills (n = 36) and patch • Structural neuroimaging | • Range = 42-58 y • 5-36 mo since LMP • TSM: Average 19.3 y since LMP | • Benton Visual Retention Test • Controlled Oral Word Association Test • CVLT • Digit Span • Digit Symbol Test • Letter-Number Sequencing • Modified MMSE • NYU Paragraph Recall • Stroop Test • Trail Making Test A and B • Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale • Wechsler Memory Scale | Behavioral None Neuroimaging CEE for 4 y: ventricular volume increased | No information on TofM, average TSM reported, but not analyzed, no information on AatM. |

| Maki PM, et al. Maturitas. 2016 Oct;92:123-129. | • n = 36 with moderate to very severe vasomotor symptoms (n = 17 received stellate ganglion blockade) • Tested at baseline and after 3 mo | • Range = 45-58 y • Menopause undefined • Induced menopause (undefined): intervention = 12%, controls = 37% | • Brief Test of Attention • CVLT • Digit Span • Finding A's • Logical Memory • Verbal Fluency • Visual Retention Test | Stellate ganglion blockade improved verbal learning and vasomotor symptoms. | Percentage induced menopause and percentage <5 y since LMP reported but not analyzed. No information on TofM or AatM. |

| Merriman JD, et al. Psychooncology. 2017 Jan;26(1):44-52. | • n = 368 • 3 groups: AI alone (n = 158), chemotherapy followed by AI (n = 104), healthy controls (n = 106) • Tested every 6 mo for 18 mo | • Mean = 59 y (not greater than 75 y; no range) • Menopause undefined • Induced menopause (undefined): controls = 15%, AI alone = 18%, chemo-AI = 19% | • Patient Assessment of Own Functioning Inventory | Chemotherapy followed by AI: poorer global cognitive function, memory, language/communication, and sensorimotor function after treatment compared to controls | Percent induced menopause reported but not analyzed. No information on TSM or AatM. |

| Meyer F, et al. Menopause. 2016 Feb;23(2):209-214. | • n = 20 experiencing fatigue and hot flashes • Open-label 4-week trial of Armodafinil | • Range = 40-65 y • Menopausal transition or postmenopausal (STRAW criteria) • Induced menopause: 25% | • Brown Attention-Deficit Disorder Scale • Cognitive and Physical Functioning Questionnaire | Armodafinil: improved cognitive function, depressive symptoms, and insomnia compared to placebo. | Percentage induced menopause reported but not analyzed. No information on TSM or AatM. |

| Peng W, et al. Aging Ment Health. 2016;20(6):647-654. | • n = 277 (n = 170 diagnosed with osteoporosis) • Serum E2, parathyroid hormone, osteocalcin, and vitamin D levels | • Mean = 71 y (no range) • Menopause undefined • TSM: Average 20 y since LMP | • Auditory Verbal Learning Test • Boston Naming Test • MMSE • Recognition test • Semantic Memory Test • Stroop Test • Trail Making Test A and B • Verbal Fluency • Visual Reasoning Test • Wisconsin Card Sorting Test | Osteoporosis: worse cognitive performance | No information on TofM, Average TSM reported, but not analyzed, no information on AatM. |

AatM, age at menopause; AI, Aromatase Inhibitor; CEE, conjugated equine estrogens; CVLT, California Verbal Learning Test; E2, 17β-estradiol; LMP, last menstrual period; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Exam; STRAW, Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop; TofM, types of menopause; TSM, time since menopause.

TABLE 4.

Articles with partial differentiation (main cognitive and brain outcomes only)

| Citation | Study | Age range, menopausal definition, and assessment | Cognitive and brain assessment | Main cognitive and brain outcomes | Category explanation |

| Bojar I, et al. Med Sci Monit. 2016c Sep;22:3469-3478. | • n = 210 • Blood FSH and E2 levels • ERα genotyping: GG (n = 35), AA (n = 71), AG (n = 104) | • Range = 50-65 y • 2+ y since LMP • FSH >30 mIU/mL • Age at LMP: 42-56 y | See Bojar et al., 2016a | No effect of AatM on cognition. ERα GG polymorphism: reduced memory and processing speed compared to ERαAA or AG (AatM not factored) | No information on TofM, TSM accounted for by analyzing chronological age and AatM. |

| Dumas JA, et al. Menopause. 2017 Feb;24(2):163-170. | • n = 18 • Testing 3 d of pharmacological regimen consisting of: bromocriptine (DA agonist), haloperidol (DA blocker), and placebo • Blood E2, estrone, and testosterone levels • Functional neuroimaging | • Range = 52-59 y • 1+ y since LMP (stages +1 and +2 of STRAW +10 staging) • TSM: Average 5.5 y since LMP • Induced menopause excluded | • Verbal n -back task | Behavioral None Neuroimaging Dopaminergic stimulation: increased brain activation in precentral gyrus and inferior parietal lobule compared to dopaminergic blockade. | TofM: Induced menopause excluded. TSM reported but not analyzed. No information on AatM. |

| Espeland MA, et al. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2017 Jun;72(6):838-845. | • n = 4,256 • 2 cohorts: n = 1,376 recent menopause (701 on HT); n = 2,880 late menopause (1,402 on HT) • WHIMS - Younger Women and Cognitive Outcome Cohorts • Tested a mean 6.8 y after HT trial | • Range = 50-54 y and 65-79 y • Menopause undefined | • Digit Span Test • East Boston Memory Test • Oral Trail Making Test • Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status-modified • Verbal Fluency | HT in late menopause: decrements in global cognitive function, working memory, and executive function | No information on TofM, no specific information on TSM but recent vs late covaried, No information on AatM. |

| Hampson E, et al. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2016 Feb;64:99-107. | • n = 99 (n = 64 on HT) • Salivary cortisol before testing and halfway through, randomized by time of day | • Range = 45-65 y • 1+ y since LMP • Age at LMP: 40-58 y | • CVLT • Digit Span Forward task | Higher cortisol levels associated with better recall and fewer memory errors. | No information on TofM or TSM, AatM reported for each HT group, number of women with early menopause was equal across groups. |

| Henderson VW, et al. Neurology. 2016;87(7):699-708. | • n = 567 • Two cohorts: n = 234 recent menopause (121 on HT); n = 333 late menopause (163 on HT) • Early versus Late Intervention Trial with Estradiol • 3 time points: baseline, 2.5 y, and 5 y | • Range = 41-84 y • Recent menopause: 6 mo-6 y since LMP • Late menopause: 10+ y since LMP • Serum E2<25 pg/mL • Induced menopause (bilateral oophorectomy): recent HT = 4.1%, recent placebo = 1.8%, late HT = 14.1%, late placebo = 17% | • Block Design • Boston Naming Test • CVLT • East Boston Memory Test • Faces I and II • Judgment of Line Orientation • Letter-Number Sequencing • Shipley Abstraction scale • Symbol Digit Modalities Test • Trail Making Test • Verbal Fluency | Induced and spontaneous menopause: no difference in global cognition | TofM: subgroup analysis of spontanous vs induced menopause, TSM, AatM reported for each HT group, number of women with early menopause was equal across groups but not controlled for in subgroup analysis. |

| Imtiaz B, et al. J Alzheimers Dis. 2017;56(2):453-458. | • n = 731 • Three groups: HT never (n = 488), HT for ≤5 y (n = 116), HT for >5 y (n = 127) • 2 timepoints: baseline and follow-up after mean of 8.3 y | • Range = 65-79 y • Menopause undefined • Induced menopause (hysterectomy with bilateral oophorectomy): HT never = 11.9%; HT ≤5 yrs = 21.9%; HT>5 yrs = 27.8% | • Bimanual Purdue Pegboard Test • Category Fluency • Immediate Word Recall • Letter-Digit Substitution Test • MMSE • Stroop test | HT use >5 y: better episodic memory at baseline but not follow-up | TofM: Gynecological surgery analysis stratified by type of surgery, no information on TSM or AatM. |

| Janelsins MC, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2017 Feb 10;35(5):506-514. | • n = 945 (n = 505 with invasive breast cancer) • 3 time points: prechemotherapy, within 4 wk of chemotherapy end, 6 mo after second time point. | • Range = 22-81 y • Menopause undefined • Pre- and postmenopausal • Induced menopause (udefined): menopausal cancer patients = 8.8%, menopausal noncancer controls = 10.4% | • Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy - Cognition scale | Chemotherapy: worse cognition compared to controls. Postmenopausal status pre-chemotherapy predicted perceived cognitive impairment. | TofM: pre, peri, post, induced analyzed, no information on TSM or AatM. |

| Lal C, et al. Sleep Breath. 2016 May;20(2):621-626. | • n = 254 (n = 154 high risk for obstructive sleep apnea syndrome) | • Range = 45-60 y • 1-5 y since LMP • Induced menopause excluded | Mail-In Cognitive Function Screening Instrument | Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: worse objective cognition and higher diagnosis of depression | TofM: Induced menopause excluded, no information on TSM or AatM. |

| Li FD, et al. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;49(1):139-47. | n = 4,796 • Reproductive period: age at menopause minus age at menarche. • Reproductive history included number of pregnancies, contraceptive use, and regularity of periods • Lifetime estrogen exposure effect on cognition | • Mean = 69.8 y (all participants >65; no range) • Menopause undefined • Average age at LMP: 49.3 y | • Chinese-language version of the MMSE | Lower lifetime estrogen exposure: increased risk of cognitive impairment Use of oral contraceptives: improved cognition. | No information on TofM, TSM: analyzed chronological age and AatM. |

| Rettberg JR, et al. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;40:155-163. | • n = 502 (n = 216 recently menopausal) • ELITE study • 3 metabolic clusters: high blood pressure, healthy, poor • 3 time points: baseline, 2.5 y, and 5 y | • Mean = 60.5 y (no range) • Serum E2<25 pg/mL • Recent menopause: 6 mo-6 y since LMP • Late menopause: 10+ y since LMP • TSM: average high blood pressure = 10.4 y, healthy = 9.9 y, poor = 11.5 y | • Block Design • Boston Naming Test • CVLT • East Boston Memory Test • Faces I and II • Judgment of Line Orientation • Letter-Number Sequencing • Shipley Abstraction scale • Symbol Digit Modalities Test • Trail Making Test • Verbal Fluency | Poor metabolic cluster: lower executive function, global memory, and cognitive performance at baseline All with HT: better global cognition and verbal memory | No information on TofM, TSM: average with recent vs late covaried, no information on AatM. |

| Shanmugan S, et al. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017 Jan;42(2):437-445. | • n = 14 • Onset of executive function difficulty during menopause • 4 week Lisdexamfetamine trial, 2 week washout, 4 week placebo (counterbalanced) • Functional neuroimaging | • Range = 45-60 y • Perimenopausal and postmenopausal • Postmenopause: 1-5 y since LMP, serum FSH levels >35 IU/L • TSM: average 2.7 y | • Brown Attention Deficit Disorder Scale • Letter n -back task • NYU Paragraph Recall task • Penn Continuous Performance Task Neuroimaging • Fractal n -back task | Behavioral Treatment: improved executive function Neuroimaging Treatment: increased activation in insula and DLPFC, and decreased DLPFC glutamate and glutamine levels Improved executive function correlated with activation of insula and DLPFC | TofM: “menopause transition,” tight age, and LMP range suggest spontaneous menopause, TSM: mean reported but not analyzed. No information on AatM. |

| Unkenstein AE, et al. Menopause. 2016 Dec;23(12):1319-1329. | • n = 130 (n = 40 postmenopausal) | • Range = 40-60 y • Peri and postmenopausal • Menopause: 1+ y since LMP • Induced menopause excluded | Objective • Boston Naming Test • Category fluency • Controlled Oral Word Association Task • Digit Span • Logical Memory • Rey Auditory Verbal Learning Test • Rey Complex Figure Test • Stroop test • Symbol Digit Modality Test • Trail Making Test B • Visual Elevator Counting Subjective • Multifactorial Memory Questionnaire | Objective None Subjective Perimenopausal: worse memory and more frequent memory lapses. | TofM: induced menopause excluded. No information on TSM or AatM. |

| Unkenstein AE, et al. Menopause. 2017 May;24(5):574-581. | • n = 32 • 4-week memory strategies course • 4 time-points: 1 month before course, during course, post-course, 3 mo post-course | • Range = 47-60 y • Perimenopausal and postmenopausal • Perimenopause: self-reported variable menses • Menopause: 1+ y since LMP • Induced menopause excluded | • Multifactorial Memory Questionnaire | Memory course participants: improved memory fewer everyday memory lapses, and increased satisfaction with memory. | TofM: induced menopause excluded. No information on TSM or AatM. |

| Vega JN, et al. Front Neurosci. 2016 Sep 23;10:433. | • n = 31 (n = 15 subjective cognitive complaints) • Functional neuroimaging | • Mean = 56 y (no range) • 1+ y since LMP • Induced menopause excluded | Objective • Brief Cognitive Rating Scale • Mattis Dementia Rating Scale Subjective • CCI Neuroimaging • Selective Reminding Task | Objective and Subjective None Years since menopause: no correlation with CCI Neuroimaging Higher CCI positively correlated with functional connectivity in right middle temporal gyrus, but negatively in left middle frontal gyrus. | TofM: induced menopause excluded. TSM and chronological age analyzed for subjective complaints but not cognitive and brain outcomes; No information on AatM. |

AatM, age at menopause; CCI, Cognitive Complaint Index; CVLT, California Verbal Learning Test; DA, dopamine; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; E2, 17β-estradiol; ERα=Estrogen Receptor α; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; HT, hormone therapy; LMP, last menstrual period; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Exam; STRAW, Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop; TofM, types of menopause; TSM, time since menopause.

TABLE 5.

Papers with full differentiation (main cognitive and brain outcomes only)

| Citation | Study | Age range, menopausal definition, and assessment | Cognitive and brain assessment | Main cognitive and brain outcomes | Category explanation |

| Jacobs EG, et al. J Neurosci. 2016 Sep 28;36(39):10163-10173. | • n = 186 • Four groups: men (n = 94), premenopausal (n = 32), perimenopausal (n = 29), postmenopausal (n = 31) • New England Family Study • Blood E2, progesterone, and testosterone • Functional neuroimaging | • Range = 45-55 y • Cycling and postmenopause (STRAW stage +1c) • Menopause defined by STRAW + 10 menstrual cycle characteristics and FSH levels | • American Adult Reading Test • Controlled Oral Word Fluency • Digit Span Backwards • Verbal Fluency Neuroimaging • 12-item FNAME • 6-trial Selective Reminding Test • Verbal encoding task | All: lower E2 correlated with lower left hippocampal activity Postmenopausal: lower task-related left hippocampal activity; increased task-related bilateral hippocampal connectivity compared to pre-, peri-, and men. Low-performers had the greatest task related hippocampal connectivity | TofM: “menopause transition,” tight age, and LMP range suggest spontaneous menopause, TSM and AatM: STRAW stages and controlled for chronological age. |

| Jacobs EG, et al. Cereb Cortex. 2017 May 1;27(5):2857-2870. | • n = 141 • Four groups: men (n = 62), premenopausal (n = 26), perimenopausal (n = 23), postmenopausal (n = 20) • New England Family Study • Blood E2, progesterone, testosterone, LH and FSH levels • Functional neuroimaging | • Range = 46-55 y • see above citation for details | • Digit Span Backwards • Controlled Oral Word Fluency • Verbal Fluency • American Adult Reading Test Neuroimaging • Verbal working memory n -back task | Behavior None Neuroimaging All groups: higher E2 and progesterone correlated with task-related hippocampal deactivation Post & -Peri>Pre: task-related DLPFC and hippocampal activity Post > Pre: task-related DLPFC connectivity | TofM: “menopause transition,” tight age, and LMP range suggest spontaneous menopause, TSM and AatM: STRAW stages and controlled for chronological age. |

| Kantarci K, et al. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;53(2):547-556. | • n = 68 • 3 groups: CEE (n = 17), transdermal E2 (n = 21), or placebo (n = 30) for 4 y • Kronos Early Estrogen Prevention Study • Tested 3 y after HT completion • Structural neuroimaging | • Range = 52-65 y • 5-36 mo since LMP • Induced menopause excluded | • CVLT • Digit Span • NYU Paragraphs • Stroop test • Trail Making Test A and B • Venton Visual Retention Test • Verbal Fluency • Wechsler Digit Symbol Coding • Wechsler Letter-Number Sequencing | CEE: lower verbal learning and memory scores than placebo, no association with Aβ plaques | TofM: Induced menopause excluded, TSM and AatM: Tight age range. |

| Karim R, et al. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2016;64(12):2448-2456. | • n = 830 • WISH and ELITE study • Reproductive history | • Range = 41-92 y • 6+ mo since LMP • Induced menopause excluded | • Block Design • Boston Naming Test • CVLT • East Boston Memory Test • Faces I and II • Judgment of Line Orientation • Letter-Number Sequencing • Shipley Abstraction scale • Symbol Digit Modalities Test • Trail Making Test • Verbal Fluency | Longer reproductive period: greater global cognition and executive function | TofM: Induced menopause excluded, TSM and AatM: length of reproductive period. |

| Karlamangla AS, et al. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169008. | • n = 2,124 • Followed annually into menopause for at least 3 y, up to 12 y | • Mean = 54 y (no range) • Premenopause (at least one menstrual period in last 3 mo) • Average age at LMP: 52 y | • Digit Span Backwards • East Boston Memory Test • Symbol Digit Modalities Test | With each year after LMP, processing speed and delayed verbal memory declined | TofM: interim hysterectomy and/or oophorectomy before spontaneous menopause covaried. TSM: independent variable, AatM: combination of TSM and chronological age. |

| Kurita K, et al. Fertil Steril. 2016 Sep 1;106(3):749-756.e2 | • n = 926 (n = 123 with bilateral oophorectomy) • Combined data from WISH, ELITE, and B-Vitamin Atherosclerosis Intervention Trial (BVAIT) • Follow-up average after 3 y | • Mean = 60.7 y (no range) • 6+ mo since LMP • Unilateral oophorectomy excluded • Induced menopause (bilateral oophorectomy): WISH = 10.7%, ELITE = 12.6%, BVAIT = 20.1% | See Karim et al, 2016 | Oophorectomy after spontaneous menopause: No correlation with cognitive performance Oophorectomy after 45: lower performance in verbal learning at baseline compared with spontaneous menopause Oophorectomy before 45: decline in semantic and visual memory | TofM and AatM: analyzed age at surgery/surgery after menopause. TSM: combination of AatM and chronological age. |

| Rentz DM, et al. Menopause. 2017 Apr;24(4):400-408. | • n = 203 • Four groups: men (n = 106), premenopausal (n = 36), perimenopausal (n = 29), postmenopausal (n = 32) • New England Family Study • Blood E2, progesterone, and testosterone levels • Functional neuroimaging | • Range = 46-55 y • See Jacobs et al., 2016 for details | • American Adult Reading Test • Controlled Oral Word Fluency • Digit Span Backwards • Verbal fluency Neuroimaging • FNAME • Selective Reminding Test | All: higher E2 levels associated with better selective reminding test and FNAME performance Pre- and peri-menopausal: better than postmenopausal women on FNAME and selective reminding task | TofM: “menopause transition,” tight age, and LMP range suggest spontaneous menopause, TSM and AatM: STRAW stages and controlled for chronological age. |

| Serrano-Guzmán M, et al. Menopause. 2016 Sep;23(9):965-973. | • n = 52 (n = 27 intervention) • Guided dance therapy vs self-directed treatment • Tested at baseline and after 2 mo | • Mean = 69.3 y (no range) • 1+ y since LMP • Diagnosed with spontaneous menopause by clinician | • Quality of Life questionnaire • Timed get-up-and-go task | Intervention: improvement in cognitive timed up-and-go task compared to controls. | TofM, TSM, AatM: all participants spontaneous menopause. |

| Triantafyllou n, et al. Climacteric. 2016;19(4):393-399. | • n = 39 • Seeking treatment for subjective memory complaints • Blood E2 and FSH | • Mean = 58.7 y (no range) • 1+ y since LMP • FSH>25 mIU/mL • E2<50 pg/mL • TSM: between 1 and 33 y (average 10 y) • Induced menopause excluded | Objective • Brief Visuospatial Memory Test • Clock Drawing Test • HVLT • MMSE Subjective • Greene's Climacteric scale | Psychological symptom severity and low circulating E2 correlated with lower MMSE and visuo-spatial memory. Vasomotor symptom severity correlated with worse total, delayed, and retained verbal learning. | TofM: POI and induced menopause excluded, TSM: covaried, AatM: TSM and chronological age. |

AatM, age at menopause; CEE, Conjugated Equine Estrogens; CVLT, California Verbal Learning Test; DLPFC, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; ELITE, Early vs Late Intervention Trial of Estradiol study; E2, 17β-estradiol; FNAME, Face Name Associative Memory Exam; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; LH, luteinizing hormone; LMP, last menstrual period; NYU, New York University; POI, premature ovarian insufficiency; STRAW, Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop; TofM, types of menopause; TSM, time since menopause; WISH, Women's Isoflavone Soy Health study.

The 2 RCTs had full differentiation because they only recruited midlife women in spontaneous menopause. One study looked at the cognitive effect of hormone therapy (HT) on women carrying an APOE4 allele compared with those on placebo. They found that women on conjugated equine estrogens (CEE) had lower verbal learning and memory scores than those on placebo,84 suggesting that CEE is not beneficial for women with APOE4. The other RCT looked at the effect of 2 months of exercise on executive function. This study demonstrated an improvement in executive function following this intervention.85

Two observational studies had full differentiation because they investigated the effects of TSM or since LMP on cognitive performance. One which recruited only spontaneously postmenopausal women used TSM to calculate total reproductive period and found that global cognition and executive function improved the longer the reproductive period.86 The other recruited women before menopause, following them annually as they went into menopause (up to 12 y). Time since LMP was used to determine the effect of menopause duration on processing speed and verbal memory. Most women were spontaneously menopausal but a few had surgical menopause, which was controlled for in the analysis. This study found that cognitive performance declined longitudinally with each year after LMP,87 suggesting that time in menopause negatively affects cognition.

One study in a range of ages likely included both women in spontaneous and early menopause, but differentiated fully by controlling for age at menopause by using time since LMP and chronological age as covariates. They found that lower circulating E2 was associated with decreased total and delayed visuospatial memory, reduced verbal learning, and lower Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) scores,88 suggesting that E2 may be important for maintaining cognitive performance.

Three studies from a longitudinal cohort, The New England Family Study, classified menopause using the STRAW + 10 criteria, comparing cognition and brain activity of premenopausal, perimenopausal, and early postmenopausal women (stage −3b and +1c) and men. The age of the participants ranged from 45 to 55 years, which suggests that only women in spontaneous menopause were recruited. Strengthening the design, participants with endocrine disorders were excluded, suggesting that participants with POI were also excluded.89-91 Without an explicit statement to the contrary, it is possible some participants may have entered early menopause. These three studies found that higher E2 levels were associated with better working memory and increased task-related hippocampal deactivation and prefrontal cortex connectivity, suggesting E2 has a role in memory-related brain activation.89-91

One study explicitly assessed the effects of type and age of menopause on cognition. Women with bilateral oophorectomy (BO) were compared at baseline and at 2.7 years postsurgery. No significant effect of oophorectomy was observed on cognition or cognitive decline compared with women with intact ovaries.92 When stratified by age at BO, however, women who had a BO before 45 years had a greater decline in semantic memory and global cognition compared with controls, whereas those with BO after 45 years had lower verbal learning performance at baseline and a greater decline in executive function and visual memory compared with controls. Women with BO after spontaneous menopause did not differ from controls in any cognitive domain.92

DISCUSSION

To clarify the types of menopause used in studying its effects on cognition, we undertook a classification of the 2016 literature on menopause and cognition according to whether or not and how menopausal types were differentiated. We looked for three important dimensions of menopause found to influence cognition:18,93-95

-

1.

How (type of menopause: spontaneous, early, induced, or POI)

-

2.

When (age at menopause)

-

3.

How long (TSM)

According to different permutations and combinations of how these dimensions were used in the design and analysis of studies, we assigned each study a typology: undifferentiated, demographic differentiation, partial differentiation, and full differentiation. We further suggest that ovary-sparing hysterectomy be considered early menopause if the hysterectomy is carried out before the age of 45, due to the fact that it may also lower age at menopause7,8; the gradual nature of ovarian cessation suggests that it should not be considered induced menopause.14

A total of 50 research articles were retrieved. We found that 38% of the articles were undifferentiated, 16% had demographic differentiation, 28% partially differentiated, and 18% of the articles fully differentiated. We are aware that many studies used longitudinal data that may have been collected up to 20 years ago using databases that did not collect all the information about menopausal type, and that studies published in 2016 are often carried out 3 to 4 years earlier. Thus, we acknowledge that a lag time in incorporating current knowledge may have played a role in some of the studies not differentiating menopausal types. Although it would have been interesting to compare cognitive outcomes across the four types of differentiation, we believe that the less a study differentiated the type or TSM, the less clear the cognitive outcomes; thus, we do not believe that such a comparison would be informative. However, the studies that differentiated generally showed a significant effect of type and age at menopause, emphasizing the importance of analyzing these dimensions in cognitive research.

Previous literature on differentiating menopausal type

Our study is the first to develop a typology to survey the literature for menopausal differentiation. It is not the first to suggest that it is scientifically important to incorporate these distinctions in the design and analysis of cognitive studies. The growing understanding that early and surgical menopause, especially before age 45, has effects on all aspects of health, especially cognition,16,96 has generated numerous papers calling for studying women with early menopause. In particular, continued work by the Rochester Epidemiology Group proposes the differentiation of surgical from spontaneous menopause, especially with respect to the treatment of postmenopausal women who undergo menopause before 45 years old.93-96 This has led to the suggestion that women with oophorectomy and POI before the age of spontaneous menopause should be treated with hormone therapy to bring their estrogen levels to levels similar to that of cycling women.6,93

Clinical guidelines

Clinical guidelines have also focused on differentiating the types of menopause. The 2014 North American Menopause Society (NAMS) guidelines and the 2015 Endocrine Society clinical guidelines reference the importance of considering menopausal types and context in treatment, particularly with respect to cognitive complaints.3,6 Based on clinical observation and accumulating research around menopause experience for women, both sets of clinical guidelines advocate differentiating menopausal types: spontaneous (average menopause around 51 y), early (before age 45), premature (before age 40), and induced (ovarian removal or ablation before spontaneous menopause). The clinical recommendations in these guidelines cover therapies for the most common symptoms of spontaneous menopause and, to an extent, spontaneous or induced early menopause.3,6

The Endocrine Society cautions against using typical symptom management techniques for women with either premature or induced menopause, due to the lack of evidence specific to these groups, particularly the group with POI.6 These guidelines are endorsed by many international menopause societies, including NAMS. Within the NAMS guidelines, the only explicit difference in treatment recommendations is for cognitive complaints between spontaneous and induced-postmenopausal women. They recommend that “[w]omen who undergo oophorectomy before age 48 years may be advised that taking estrogen therapy (ET) until the typical age at menopause appears to lower the risk of dementia later in life.3” The results of our study show that, despite a call for differentiating menopausal context, a large proportion of the recent menopausal research remains undifferentiated, which may preclude successful translation of research into clinical practice.

These guidelines prioritize level I evidence, or “good and consistent scientific evidence.”3 For treatment recommendations, level I evidence most often comes from double-blind, placebo-controlled RCTs.97,98 The 19 articles in this review that did not account for menopausal type included 40% of all RCTs (6 out of 15 total RCTs). Even studies that did take into account some aspect of the guidelines fell short of completely incorporating menopausal differentiation into their design and/or analysis. For example, studies that the recruited older women (60+) were more likely to not state the reason for menopause or the age at which participants went into menopause.99,100

Studies of health conditions other than cognition in menopausal populations, that instead use cognition as an outcome, should begin to shape their studies according to these guidelines. For example, cognitive outcomes after cancer treatment are critically important to understand, and yet our results show that the majority of studies of the cognitive outcomes of cancer therapy (7 articles out of 10) neglected to differentiate the age of menopause or type of menopause. This is a problem for noncancer studies as well because many of them recruit participants from clinics, suggesting that there might be an overrepresentation of women with induced menopause in those studies. For example, in demographically differentiated studies, we observed that proportions of induced postmenopausal women ranged from 17% to 25% when reported (Table 3), significantly surpassing our best calculation for the frequency in the general population (approximately 6%, as derived from the Women's Health Initiative study4).

We found that research which fully differentiated menopausal context yielded clinically relevant findings. Although comparing cognitive outcomes across typologies was not feasible due to the wide range of cognitive outcomes, clinical populations, and mixed menopause reporting, we wanted to focus on one study that emphasized the value of differentiation and found significant differences. Kurita et al compared induced and spontaneous menopause, and found no significant cognitive differences when induced menopause (oophorectomy-ever) was analyzed as a pooled sample, but revealed worse verbal and spatial memory in women with earlier induced menopause after splitting the group into age at oophorectomy.92 Furthermore, they controlled for factors disproportionately present in early or induced menopause that are also known to affect cognition—BMI, education, race/ethnicity, smoking—potentially contributing to greater validity of their findings.92 In cardiovascular research, this greater specificity is viewed as important to understanding the outcomes of induced menopause;6 for example, further covarying for age, race, education, BMI, and other health-related factors revealed an increased risk of diabetes in women with combined hysterectomy–oophorectomy compared with women who had spontaneous menopause or hysterectomy only.101,102,103 This demonstrates that demographic specificity, even within a menopause type, strengthens the evidence for clinical evaluations and treatment.

Recommendations for future clinical studies

Consider menopause types as part of the research design.

Differentiate menopauses according to the Endocrinology and NAMS guidelines and use the terminology consistently (POI, early, induced, ovary-sparing hysterectomy, spontaneous).

-

Acknowledge and describe menopausal population fully in research methods by collecting the following information:

-

∘

chronological age;

-

∘

age at menopause or how long a person has been in menopause;

-

∘

whether it was induced or spontaneous;

-

∘

if induced, if it is due to drug treatment (eg, chemotherapy) or ovarian removal; and

-

∘

other demographic information associated with the many menopauses: BMI, education, race/ethnicity, and smoking.

-

∘

Include demographic information mentioned above even when using physiological measures of menopausal transition (FSH, E2 levels).

To acquire strong evidence to inform clinical guidelines for the treatment of different types of menopause, studies need to make explicit choices in design, recruitment, and analysis to account for menopausal types. When reporting, it is critical to clearly describe the distribution of menopausal types and age at menopause. In analysis, best evidence comes from disaggregating the types of menopause. Even if there is no hypothesized difference in outcomes between the types of menopause, it is better to confirm there is no difference than assume there is none. The first step is to acknowledge that there are many menopauses.

Strengths and limitations of the current analyses

This is the first review of the literature to provide a thorough analysis in one year of publications of how menopause is conceptualized and analyzed in studies of cognition in postmenopausal women. This analysis allows for a novel perspective on menopausal research that generates specific recommendations to further our understanding of the specific effects of the many menopauses on cognition.

To thoroughly review the literature, we focused on studies of cognition and menopause published in 2016. Although it is possible that more recent publications or studies outside of cognition may have more fully differentiated papers, we believe that one year and one domain gives an in-depth understanding of the variations in the research questions, design, and analysis. As is the case in most scientific research, the studies included in our analysis were based on data collected a number of years ago when the awareness of the different outcomes of different types of menopause were not well understood. That being said, the absence of menopausal information should be acknowledged.

We included some studies that were not specifically about the effects of menopause on cognition, but rather studies that simply looked at cognitive performance in postmenopausal women. For example, many of the studies of cancer treatment in postmenopausal women focused more on cognitive changes after treatment rather than after menopause. These studies were important to include because they still studied cognitive function in different types of menopause. We note that, although it is challenging to always adopt the perspective that includes the variations in menopause when it is not explicitly the focus of the study, it would add richness to these studies to be clear about the age of, reason for, and TSM.

A limitation of this paper is that we were not able to quantify potential differences in cognitive outcomes across differentiation typologies. We felt that to do so would not yield meaningful results precisely because menopausal criteria were not clear except in the category of full differentiation. We instead focused on a series of studies in the same women that ultimately did fully differentiate to good effect. Our study did, however, establish a typology which future studies can use as a weighting scale in future meta-analyses that take multiple years into account. Ideally, further research would examine differences in cognition across menopause types to clarify risks and outcomes for all types of menopause, particularly in women with nonspontaneous menopause.

The current analysis presents only quantitative research on cognition in postmenopausal women. This could be explained in part because our search terms did not pull up any qualitative studies that were specifically exploring cognition. Mixed method approaches have the advantage of gaining information that is richer and contextualized by revealing different aspects of the same issue, allowing for important insights to be gained that might otherwise be invisible. Thus, qualitative studies of women's own sense of their cognitive abilities in the many menopauses would be an important area to explore.

CONCLUSIONS

There is no single pathway to the end of menses. Menstruation ceases for different reasons, in different ways, at different time points in the lifespan, with different symptom experiences and health risks. Differentiating between menopausal types in research is an important step toward clarifying the uniqueness of menopause experience for each woman. Acknowledging menopausal types in design and analysis is an important next step for clinical research. The absence of menopausal differentiation in one year of research alone suggests that menopause remains for many a monolithic and uniform process. When taking the many menopauses into account, differences in memory and cognitive outcomes are seen for each type of menopause. Explicitly acknowledging the many menopauses will allow for more rigorous clinical research and the development of clinical guidelines that are applicable to each type of menopause in all women.

Acknowledgments

We thank the early contributions of Drs. Kelly Evans and Michelle Skop. Yael Schwartz contributed to the literature review.

Footnotes

Funding/support: This research was funded by Canadian Cancer Society grant #310336, CIHR Operating Grant #FRN 130490, and the Canadian Consortium on Neurodegeneration and Aging to GE as well as the Enid Walker Graduate Student Award in Women's Health Research, Women's College Hospital to ASA.

Financial disclosure/conflicts of interest: None reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harlow SD, Gass M, Hall JE, et al. Executive summary of the stages of reproductive aging workshop + 10: addressing the unfinished agenda of staging reproductive aging. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97:1159–1168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hale GE, Robertson DM, Burger HG. The perimenopausal woman: endocrinology and management. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2014; 142:121–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shifren JL, Gass MLS. The North American Menopause Society recommendations for clinical care of midlife women. Menopause 2014; 21:1038–1062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shadyab AH, Macera CA, Shaffer RA, et al. Ages at menarche and menopause and reproductive lifespan as predictors of exceptional longevity in women: the Women's Health Initiative. Menopause 2017; 24:35–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Adamopoulos DA, Karamertzanis M, Thomopoulos A, Pappa A, Koukkou E, Nicopoulou SC. Age at menopause and prevalence of its different types in contemporary Greek women. Menopause 2002; 9:443–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stuenkel CA, Davis SR, Gompel A, et al. Treatment of symptoms of the menopause: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2015; 100:3975–4011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trabuco EC, Moorman PG, Algeciras-Schimnich A, Weaver AL, Cliby WA. Association of ovary-sparing hysterectomy with ovarian reserve. Obstet Gynecol 2016; 127:819–827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moorman PG, Myers ER, Schildkraut JM, Iversen ES, Wang F, Warren N. Effect of hysterectomy with ovarian preservation on ovarian function. Obstet Gynecol 2011; 118:1271–1279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuh JL, Wang SJ, Lee SJ, Lu SR, Juang KD. A longitudinal study of cognition change during early menopausal transition in a rural community. Maturitas 2006; 53:447–453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Henderson VW, Popat RA. Effects of endogenous and exogenous estrogen exposures in midlife and late-life women on episodic memory and executive functions. Neuroscience 2011; 191:129–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weber MT, Maki PM, McDermott MP. Cognition and mood in perimenopause: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 2014; 142:90–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Luetters C, Huang MH, Seeman T, et al. Menopause transition stage and endogenous estradiol and follicle-stimulating hormone levels are not related to cognitive performance: cross-sectional results from the study of women's health across the nation (SWAN). J Womens Health 2007; 16:331–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Farrag AF, Khedr EM, Abdel-Aleem H, Rageh TA. Effect of surgical menopause on cognitive functions. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2002; 13:193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bove R, Secor E, Chibnik LB, et al. Age at surgical menopause influences cognitive decline and Alzheimer pathology in older women. Neurology 2014; 82:222–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sherwin BB. Estrogen and memory in women: how can we reconcile the findings? Horm Behav 2005; 47:371–375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rocca WA, Bower JH, Maraganore DM, et al. Increased risk of cognitive impairment or dementia in women who underwent oophorectomy before menopause. Neurology 2007; 69:1074–1083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nappi RE, Sinforiani E, Mauri M, Bono G, Polatti F, Nappi G. Memory functioning at menopause: impact of age in ovariectomized women. Gynecol Obstet Invest 1999; 47:29–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ryan J, Scali J, Carrière I, et al. Impact of a premature menopause on cognitive function in later life. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 2014; 121:1729–1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall JE. Endocrinology of the menopause. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2015; 44:485–496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prior JC. Perimenopause lost—reframing the end of menstruation. J Reprod Infant Psychol 2007; 24:323–335. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Treloar AE. Menstrual cyclicity and the pre-menopause. Maturitas 1981; 3:249–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Longcope C, Franz C, Morello C, et al. Steroid and gonadotropin levels in women during the peri-menopausal years. Maturitas 1986; 8:189–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grant MD, Marbella A, Wang AT, et al. Menopausal symptoms: comparative effectiveness of therapies. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). Report No. 15-EHC005-EF. 2015. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmedhealth/PMH0073377 Accessed September 10, 2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Coulam CB, Johnson PM, Ramsden GH, et al. Occurrence of ectopic pregnancy among women with recurrent spontaneous abortion. Am J Reprod Immunol 1989; 21:105–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Welt CK. Primary ovarian insufficiency: a more accurate term for premature ovarian failure. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2008; 68:499–509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vujovic S, Brincat M, Erel T, et al. EMAS position statement: managing women with premature ovarian failure. Maturitas 2010; 67:91–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Torrealday S, Pal L. Premature menopause. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2015; 44:543–557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson LM, Covington SN, Rebar RW. An update: spontaneous premature ovarian failure is not an early menopause. Fertil Steril 2005; 83:1327–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Allshouse AA, Semple AL, Santoro NF. Evidence for prolonged and unique amenorrhea-related symptoms in women with premature ovarian failure/primary ovarian insufficiency. Menopause 2015; 22:166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pelosi E, Simonsick E, Forabosco A, et al. Dynamics of the ovarian reserve and impact of genetic and epidemiological factors on age of menopause. Biol Reprod 2015; 92:130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tawfik H, Kline J, Jacobson J, et al. Life course exposure to smoke and early menopause and menopausal transition. Menopause 2015; 22:1076–1083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siddle N, Sarrel P, Whitehead M. The effect of hysterectomy on the age at ovarian failure: identification of a subgroup of women with premature loss of ovarian function and literature review. Fertil Steril 1987; 47:94–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee DY, Park HJ, Kim BG, Bae DS, Yoon BK, Choi D. Change in the ovarian environment after hysterectomy as assessed by ovarian arterial blood flow indices and serum anti-Müllerian hormone levels. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2010; 151:82–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sarrel PM, Sullivan SD, Nelson LM. Hormone replacement therapy in young women with surgical primary ovarian insufficiency. Fertil Steril 2016; 106:1580–1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mayo Clinic. Informatino on oophorectomy (ovary removal surgery). Available at: http://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/oophorectomy/details/why-its-done/icc-20314908 Accessed January 15, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Bachmann G. Physiologic aspects of natural and surgical menopause. J Reprod Med 2001; 46:307–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chakravarti S, Collins WP, Newton JR, et al. Endocrine changes and symptomatology after oophorectomy in premenopausal women. Br J Obstet Gynaecol 1977; 84:769–775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kotsopoulos J, Shafrir AL, Rice M, et al. The relationship between bilateral oophorectomy and plasma hormone levels in postmenopausal women. Horm Cancer 2015; 6:54–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rodriguez M, Shoupe D. Surgical menopause. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2015; 44:531–542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]