Abstract

Preoperational hemogram parameters have been reported to be associated with the prognosis of several types of cancers. This study aimed to investigate the prognostic value of hematological parameters in gastric cancer in a Chinese population. A total of 870 gastric cancer patients who underwent radical tumorectomy were recruited from January 2008 to December 2012. Preoperative hematological parameters were recorded and dichotomized by time-dependent receiver operating characteristic curves. The survival curves of patients stratified by each hematological parameter were plotted by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared by log-rank test. Multivariate Cox proportional hazards models were used to select parameters independently correlated with prognosis. The median age of the patients was 60 years. The median follow-up time was 59.9 months, and the 5-year survival rate was 56.4%. Results from the univariate analyses showed that low lymphocyte count (<2.05 × 109/L), high neutrophil-to-white blood cell ratio (NWR > 0.55), low lymphocyte-to-white blood cell ratio (LWR < 0.23), low lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio (LMR < 5.43), high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR > 1.44), and high platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR > 115) were associated with poor survival of gastric cancer patients. Multivariate analysis showed that low LMR (HR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.17–1.89, P = .001) was the only hematological factor independently predicting poor survival. These results indicate that preoperational LMR is an independent prognostic factor for patients with resectable gastric cancer.

Keywords: gastric cancer, hemogram parameters, overall survival, prognostic factor

1. Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the fifth most common malignancy in the world and the third most common cause of cancer-related mortality.[1,2] More than two-fifths of the world's gastric cancer cases are from China. In 2015, the incidence and mortality of gastric cancer ranked second among those of all malignant tumors in China.[3] GC is often asymptomatic at early stages. When diagnosed, almost half of the patients have already progressed to the advanced stage, and the 5-year survival rate is less than 30%.[2] Clinical stage is frequently used as a prognostic factor for gastric cancer. However, even the patients are diagnosed at the same stage, the clinical outcomes are not the same. Therefore, exploring additional parameters to predict prognosis is necessary.

Accumulating evidence indicates that inflammation is related to tumor development and progression.[4] It is thought that infection and inflammatory responses are associated with 15% to 20% of deaths from tumors worldwide.[5] Systemic inflammatory responses can impact tumor development through the inhibition of apoptosis, promotion of angiogenesis, and induction of DNA damage. Abnormalities in peripheral blood cells, such as neutrophilia, lymphopenia, and thrombocytosis, are identified as responses to systemic inflammation.[6,7] Therefore, immunity-related components of the blood, such as lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, and platelets, may have prognostic value for cancers. Previous studies reported that the NLR (neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio), PLR (platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio) and LMR (lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio) were associated with the prognosis of various cancers, such as lung cancer, bladder cancer, nasopharyngeal cancer, and prostate cancer.[8–12] NWR (neutrophil-to-white blood cell ratio), MWR (monocyte-to-white blood cell ratio), and LWR (lymphocyte-to-white blood cell ratio) have also been found to have predictive value in lung cancer and gastrointestinal stromal tumors.[11,13] For gastric cancer, studies in this field are limited, and studies have focused on only a few hematological parameters.[14,15] Hence, the purpose of this study was to identify whether hematological parameters (lymphocytes, neutrophils, monocytes, white blood cells, platelets, NLR, PLR, NWR, MWR, and LWR) predict the prognosis of patients with gastric cancer.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study population

From January 2008 to December 2012, gastric cancer patients were invited to participate in the study at the Department of Gastric and Colorectal Surgery of the First Hospital of Jilin University. Only patients who had undergone radical tumorectomy with D2 lymphadenectomy and were pathologically diagnosed with gastric cancer were included in the study. The average number of dissected lymph nodes was 20.5 ± 13.4. Patients who

-

(1)

had a history of other malignant tumors,

-

(2)

had radiotherapy or neoadjuvant chemotherapy before surgery,

-

(3)

presented with distant metastasis,

-

(4)

presented with positive surgical margins, or

-

(5)

had a history of autoimmune disease or hematopoietic system disease were excluded from analysis.

The seventh edition of the cancer staging manual of the Union for International Cancer Control/American Joint Committee on Cancer (UICC/AJCC) was used for TNM stage. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Hospital of Jilin University. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

2.2. Data collection

Within 1 week before surgery, venous blood samples were taken into EDTA tubes and mixed thoroughly. Hematological parameters were determined immediately after the blood sample collection using automatic blood analyzer (XE2100, Sysmex, Japan) in the Clinical Laboratory of the First Hospital of Jilin University. Parameters included white blood cell count (WBC), lymphocyte count (LYM), neutrophil count (NEU), monocyte count (MONO) and platelet count (PLT). The day-to-day coefficient of variations (CVs) during the study period were 3.04% for WBC, 1.49% for LYM, 1.03% for NEU, 2.32% for MONO, and 1.97% for PLT, respectively.

2.3. Follow-up

Patients were followed-up periodically after surgery by an experienced follow-up doctor. The follow-up was scheduled 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months after surgery and then every year thereafter. Information on the general status and post-operational therapy were collected during each follow-up. If the patients were dead, the date of death and causes were recorded. Survival time was defined as the duration from the date of surgery to the date of death if the patients were dead or to the date of the last successful follow-up if the patients were living or lost to follow-up.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were described as the median (interquartile range), and categorical variables were described as the frequency (percentage). Optimal cut-off values of each hematological parameter were calculated by time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves in the R language, where the difference of the true positive (TP) and false positive (FP) was the maximum in predicting the 5-year survival. Survival curves within each stratification of variables were plotted by the Kaplan-Meier method and compared by log-rank test. The Cox proportional hazard model was used for univariate and multivariate analyses. In the univariate analysis, the Bonferroni correction was used, and variables with P values less than .1 in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate model and selected by the forward stepwise method. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 18.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL) and the R language (http://www.r-project.org). All P values were 2-tailed, and a P value < .05 indicated statistical significance; in the Bonferroni correction, the P value needed to be less than .004 because 11 hematological parameters were included in the analysis.

3. Result

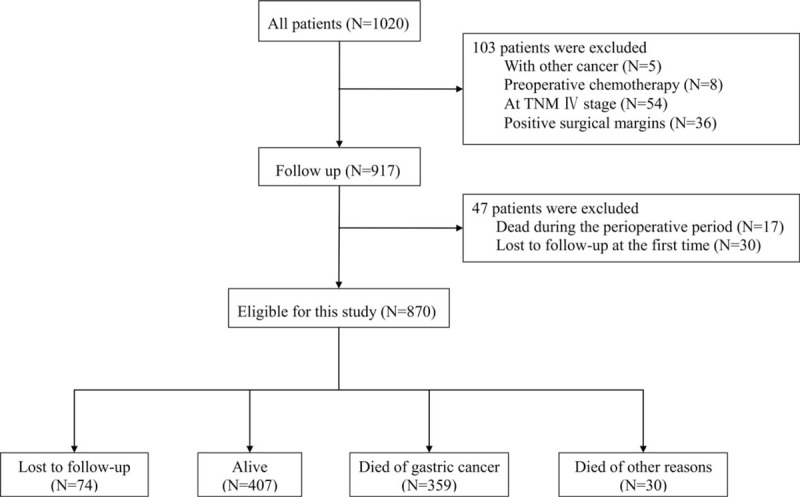

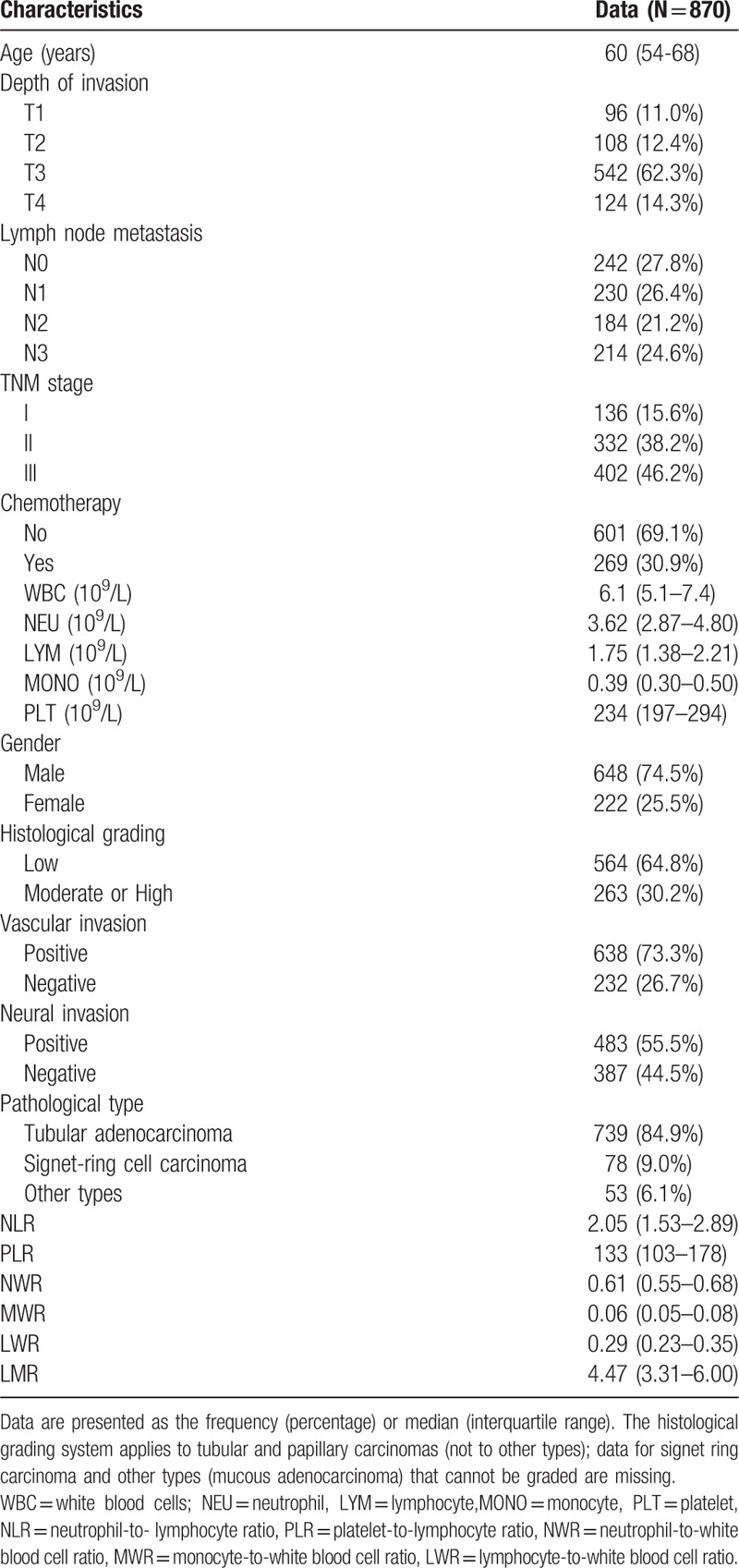

A total of 870 patients were included in this study (Fig. 1). The baseline characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. The median age of the subjects was 60 years (interquartile range, 54–68 years), and 74.5% of them were male (648/870). Nearly half (46.2%) were diagnosed at TNM stage III, 38.2% were at TNM stage II, and only 15.6% were at TNM stage I. The major pathological types were tubular adenocarcinoma (84.9%), followed by signet-ring cell carcinoma (9.0%) and other types (6.1%). Low histological classifications were dominant over moderate or high classification (64.8% vs. 30.2%). Vascular invasion (73.3%) and nerve invasion (55.5%) were observed in most patients. 30.9% of patients received postoperational chemotherapy. The chemotherapy mainly consisted of three regimens: FOLFOX-4 regimen (combination with 5-fluorouracil, leucovorin and oxaliplatin); XELOX regimen (capecitabine and oxaliplatin) and other chemotherapies such as capecitabine or 5-fluorouracil alone. Patients would be considered to have postoperative chemotherapy only if they received the therapy for at least 3 cycles.

Figure 1.

Study flow chart.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the patients included in the study.

The patients were followed up until March 1, 2017. The median follow-up time was 59.9 months. During follow-up, 389 patients (44.7%) died, 407 (46.8%) remained alive, and 74 (8.5%) were lost to follow-up. Among the patients who died, 359 died of gastric cancer, and 30 died for other reasons. The estimated 5-year survival rate was 56.4%.

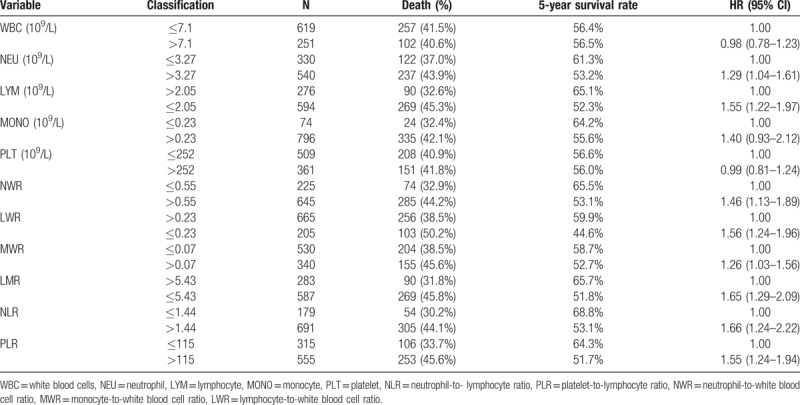

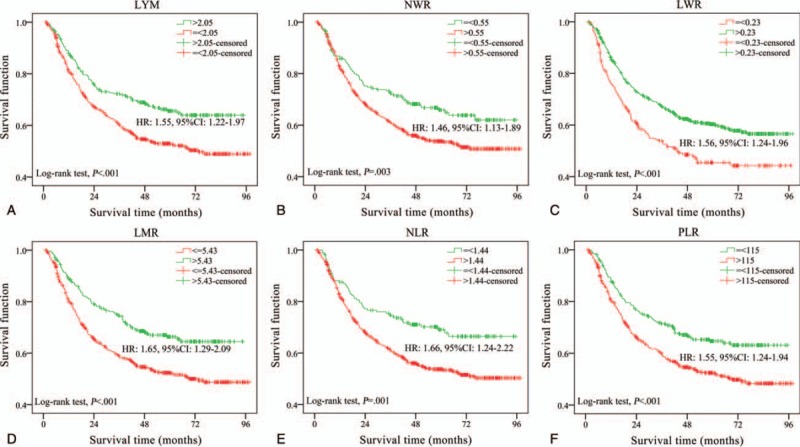

The optimal cut-off values for each parameter to best predict prognosis were obtained by time dependent-ROC, and the results are shown in Table 2. The absolute counts of white blood cells (P = .860) and platelets (P = .990) were not associated with overall survival (OS). However, white blood cells, neutrophils and lymphocytes might be related to GC prognosis. Patients with a lower lymphocyte count (LYM < 2.05 × 109/L) tended to live less time and had a lower 5-year survival rate (P < .001, Fig. 2A). Similar associations were observed for NWR (>0.55, P = .004, Fig. 2B) and LWR (< = .23, P < .001, 2C). Other indices such as LMR, NLR and PLR were found to be associated with patient prognosis in the univariate analysis. Patients tended to have shorter lifespans if their LMR was less than 5.43 (HR: 1.65, 95% CI: 1.29–2.09, P < .001, Fig. 2D). The optimal cutoff value was 1.44 for NLR, and patients with a higher NLR had a worse prognosis (HR: 1.66, 95% CI: 1.24–2.22, P < .001, Fig. 2E). Patients tended to have shorter lifespans if their PLR was higher than 115 (HR: 1.55, 95% CI: 1.24–1.94, P < .001, Fig. 2F).

Table 2.

Univariate analysis of the factors associated with the prognosis of gastric cancer.

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier curves of gastric cancer patient survival (log-rank test). The cutoff values were obtained by time-dependent ROC curve. (a) LYM, lymphocyte counts. (b) NWR, neutrophil-to-white blood cell ratio. (c) LWR, lymphocyte- to-white blood cell ratio.(d) LMR, lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio. (e) NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio. (f) PLR, platelet-to- lymphocyte ratio. LMR = lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio, LWR = lymphocyte-to-white blood cell ratio, LYM = lymphocyte counts, NLR = neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, NWR = neutrophil-to-white blood cell ratio, PLR = platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio.

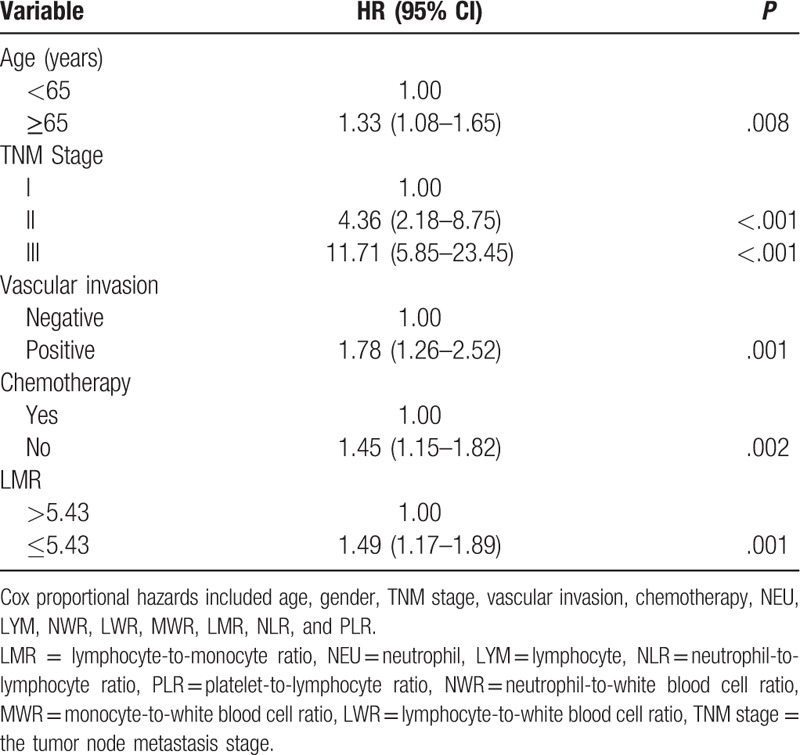

Results from the multivariate analysis showed that low LMR was an independent risk factor for shorter survival span (HR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.17–1.89, P = .001), as were old age (HR: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.08–1.65), higher TNM stage (TNM II, HR: 4.36, 95% CI: 2.18–8.75; TNM III, HR: 11.71, 95% CI: 5.85–23.45), positive vascular invasion (HR: 1.78, 95% CI: 1.26–2.52) and no chemotherapy (HR: 1.45, 95% CI: 1.15–1.82) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate analysis of the factors associated with gastric cancer prognosis.

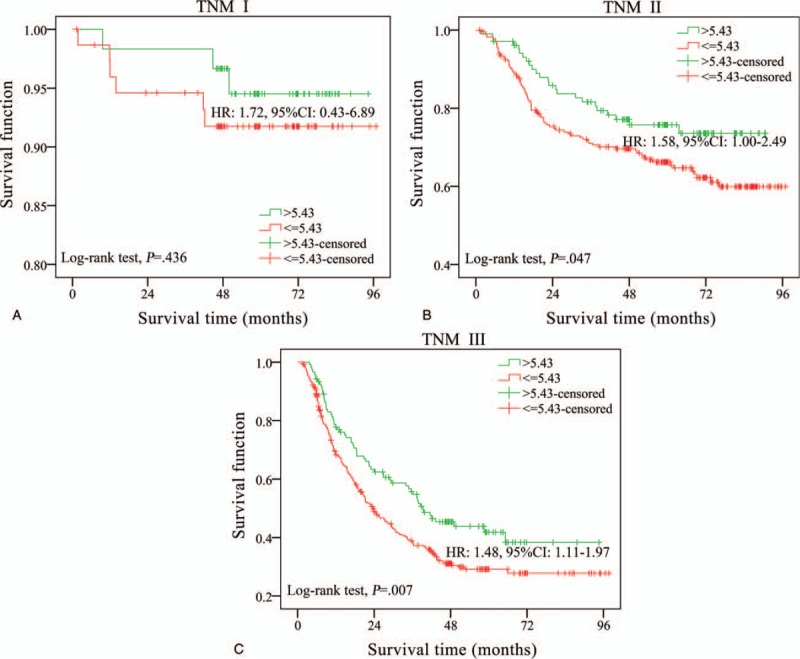

To further clarify the prognostic value of LMR, stratification analysis of the most important predictive factor, TNM stage, was performed in patients (Fig. 3). A similar association between the LMR and overall survival of GC could be observed in TNM I, TNM II and TNM III patients. However, this trend was more obvious in TNM III patients (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

Survival curves of gastric cancer patients stratified by TNM stage. (a) LMR (lymphocyte-to- monocyte ratio) levels in patients of TNM I stage. (b) LMR levels in patients of TNM II stage. (c) LMR levels in patients of TNM III stage. LMR = lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio, TNM stage = the tumor node metastasis stage.

4. Discussion

Though advances have been achieved in surgical techniques and adjuvant chemotherapy for gastric cancer in the last two decades, the prognosis of GC is still poor; it was estimated that approximately 498,000 Chinese would die from GC in 2015.[3] Hemogram parameters are readily available and one of the routine laboratory blood tests performed to evaluate the general status of patients before surgery. Previous studies have reported that hemogram parameters could predict the prognosis of various malignancies; however, the results from these studies are controversial. Therefore, the value of hemogram parameters in predicting the prognosis of tumors needs to be further clarified.

Lymphocytes are possibly indicative of tumor suppressor activity. Experimental studies have found that lymphocytes play a considerable role in tumor defense, and tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes can identify tumor cells and induce apoptotic cell death through cytotoxicity. Evidence is accumulating that lymphocytes serve as constituents of the immune complex, represent the cellular basis of cancer immunosurveillance and are involved in the inhibition of tumor cell proliferation and metastasis.[10,16] Decreased numbers of lymphocytes could induce the release of several inhibitory immunological mediators, particularly IL-10 and transforming growth factor-β.[17] In our univariate analysis, GC patients with lower lymphocyte counts tended to have shorter survival and an increased risk of death by 55 percent. However, in the multivariate analysis adjusted for other factors, lymphocyte count alone was not an independent prognostic factor. Monocytes are considered pro-tumor cells as they facilitate the progression and dissemination of tumor cells.[18,19] Monocytes could be recruited to the tumor microenvironment by tumor-derived CCL5 and promote tumor cell growth and survival.[18] On the other hand, tumor cells induce the differentiation of monocytes into tumor-associated macrophages,[20] which in turn weaken the antitumor immune response and stimulate the migration and metastatic spread of tumor cells.[18,19,21] Peripheral monocyte levels were found to be negatively associated with prognosis in patients with various types of cancer.[22–24] In our study, the results showed that increased monocyte levels were associated with a 40% increased risk of death; however, this finding did not achieve statistical significance (HR: 1.40, 95% CI: 0.93–2.12).

LMR, the ratio of lymphocytes to monocytes, is a comprehensive index that may better predict the long-term prognosis of cancer patients. LMR is reported to have prognostic value in several malignancies.[25,26] A study by Ni et al demonstrated that elevated LMR (≥4.25) was associated with favorable disease-free survival (P = .011) in locally advanced breast cancer patients.[27] Hirahara et al. found that LMR could be used as a predictor of postoperative cancer-specific survival and OS in patients with esophageal cancer and that it may be useful in identifying patients with poor prognosis even after radical esophagectomy (HR: 1.87, 95% CI: 1.09–3.23).[28] Studies on gastric cancer also found that LMR could be used to predict outcomes of gastric cancer patients undergoing surgery. Lieto et al reported that patients with a low LMR (≤3.37) had a higher hazard ratio for both overall survival (HR: 2.10; P < .001) and disease-free survival (HR: 2.46; P < .001) than high LMR subjects.[15] Hsu et al found patients with lower LMR (≤4.8) had more aggressive tumor behavior, higher surgical mortality rates, and worse long-term survival (HR: 1.36, 95% CI: 1.08–1.69).[29] In another study, Cong et al found low LMR (≤4.34) was associated with poor outcomes in 188 patients with stage II-III gastric cancer.[30] In this study, we included a relatively large sample size of gastric cancer in TNM stage I-III (HR: 1.66, 95% CI: 1.04–2.66). Consistent with the previous studies, we also observed that GC patients with lower LMR had worse prognosis. However, the optimal cutoff of LMR was 5.43 and patients with LMR < 5.43 had a shorter lifespan and a lower 5-year survival rate (HR: 1.49, 95% CI: 1.17–1.89). Moreover, subgroup analysis showed similar trends in TNM II and III patients.

Previous studies also suggested that NLR and PLR might be related to cancer patient prognosis. Neutrophils are thought to participate in the process of tumor development by cytokine production.[31] Platelets play an important role in the process of transendothelial migration, the earliest step in metastasis.[32] Studies have found that higher NLR and PLR were associated with poor prognosis in patients with endometrioid adenocarcinoma, paranasal sinus cancer, breast cancer and colorectal cancer.[33–36] In gastric cancer-related studies, NLR and PLR were also found to be independent prognostic factors.[37,38] In our study, higher NLR and higher PLR were associated with poor survival in the univariate analysis. These associations, however, diminished after adjusting for the influence of TNM stage. We found that NLR and PLR were positively correlated with TNM stage (NLR and TNM, rs = 0.141, P < .001; PLR and TNM, rs = 0.156, P < .001) and that TNM was the most powerful prognostic predictive factor of GC (AUC for 5-year survival ROC: 0.741). Therefore, NLR and PLR were not independently associated with the prognosis of GC.

Our study had limitations. Although the median follow-up time was 59.40 months, the number of deaths from gastric cancer did not reach half of the total. That may lead to decreased statistical power. Another limitation was that our study only included patients from one center, and the results were not confirmed in other centers. Therefore, generalization of the results should be done cautiously.

In conclusion, we observed that lower LMR was independently associated with poor overall survival of gastric cancer patients undergoing radical tumorectomy. LMR has the potential to be used as a biomarker to predict the prognosis of gastric cancer before surgery, and patients with lower pre-operative LMR should be under more frequent surveillance of gastric cancer and more aggressive chemotherapy. Large cohort studies are needed to confirm our results.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Zhifang Jia.

Data curation: Yuchen Pan.

Formal analysis: Yuchen Pan.

Methodology: Simin Wen, Dan Zhao.

Project administration: Jing Jiang, Xueyuan Cao.

Software: Zhifang Jia, Yanhua Wu.

Supervision: Donghui Cao, Yanhua Wu, Songling Zhang, Xueyuan Cao.

Validation: Donghui Cao, Xueyuan Cao.

Visualization: Songling Zhang.

Writing – original draft: Yuchen Pan.

Writing – review & editing: Zhifang Jia.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: FP = false positive, GC = gastric cancer, LMR = lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio, LWR = lymphocyte-to-white blood cell ratio, LYM = lymphocyte count, MONO = monocyte count, MWR = monocyte-to-white blood cell ratio, NEU = neutrophil count, NLR = neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, NWR = neutrophil-to-white blood cell ratio, OS = overall survival, PLR = platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio, PLT = platelet count, ROC = receiver operating characteristic, TNM stage = the tumor node metastasis stage, TP = true positive, WBC = white blood cells count.

Yu-Chen PAN and Zhi-Fang JIA contributed equally to this work.

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81673145, 81703293 and 81703286), Science and Technology Development Program of Jilin Province (20180414055GH) and Research fund of Department of Education of Jilin Province (2016487).

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- [1].Fock KM. Review article: the epidemiology and prevention of gastric cancer. Aliment Pharmacol Ther 2014;40:250–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Rugge M, Fassan M, Graham DY. Strong VE. Epidemiology of gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer: Principles and Practice. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2015. 23–34. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA: Cancer J Clin 2016;66:115–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Coussens LM, Werb Z. Inflammation and cancer. Nature 2002;420:860–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Balkwill F, Mantovani A, Balkwill F, et al. Inflammation and cancer: Back to Virchow? Lancet 2001;357:539–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Fu JJ, Baines KJ, Wood LG, et al. Systemic inflammation is associated with differential gene expression and airway neutrophilia in asthma. OMICS 2013;17:187–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kemp MW, Kannan PS, Saito M, et al. Selective exposure of the fetal lung and skin/amnion (but not gastro-intestinal tract) to LPS elicits acute systemic inflammation in fetal sheep. PloS One 2013;8:e63355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Tang L, Li X, Wang B, et al. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in localized and advanced prostate cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One 2016;11:e0153981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sun W, Zhang L, Luo M, et al. Pretreatment hematologic markers as prognostic factors in patients with nasopharyngeal carcinoma: neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio and platelet-lymphocyte ratio. Head Neck 2016;38: E1332-1340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Kang M, Jeong CW, Kwak C, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio can significantly predict mortality outcomes in patients with non-muscle invasive bladder cancer undergoing transurethral resection of bladder tumor. Oncotarget 2017;8:12891–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Yuan C, Li N, Mao X, et al. Elevated pretreatment neutrophil/white blood cell ratio and monocyte/lymphocyte ratio predict poor survival in patients with curatively resected non-small cell lung cancer: results from a large cohort. Thorac cancer 2017;8:350–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Nishijima TF, Muss HB, Shachar SS, et al. Prognostic value of lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio in patients with solid tumors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancer Treat Rev 2015;41:971–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Feng F, Tian Y, Liu S, et al. Combination of PLR, MLR, MWR, and tumor size could significantly increase the prognostic value for gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Medicine 2016;95:e3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Lin JP, Lin JX, Cao LL, et al. Preoperative lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio as a strong predictor of survival and recurrence for gastric cancer after radical-intent surgery. Oncotarget 2017;8:79234–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Lieto E, Galizia G, Auricchio A, et al. Preoperative neutrophil to lymphocyte ratio and lymphocyte to monocyte ratio are prognostic factors in gastric cancers undergoing surgery. J Gastrointest Surg 2017;21:1764–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Fridman WH, Pagès F, Sautèsfridman C, et al. The immune contexture in human tumours: impact on clinical outcome. Nat Rev Cancer 2012;12:298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Salazar-Onfray F, López MN, Mendoza-Naranjo A. Paradoxical effects of cytokines in tumor immune surveillance and tumor immune escape. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev 2007;18:171–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Wilcox RA, Wada DA, Ziesmer SC, et al. Monocytes promote tumor cell survival in T-cell lymphoproliferative disorders and are impaired in their ability to differentiate into mature dendritic cells. Blood 2009;114:2936–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Peng LS, Zhang JY, Teng YS, et al. Tumor-associated monocytes/macrophages impair NK-cell function via TGFbeta1 in human gastric cancer. Cancer Immunol Res 2017;5:248–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Mantovani A, Schioppa T, Porta C, et al. Role of tumor-associated macrophages in tumor progression and invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev 2006;25:315–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Mantovani A, Allavena P, Sica A, et al. Cancer-related inflammation. Nature 2008;454:436–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Wang YQ, Zhu YJ, Pan JH, et al. Peripheral monocyte count: an independent diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for prostate cancer - a large Chinese cohort study. Asian J Androl 2017;19:579–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Valero C, Pardo L, Lopez M, et al. Pretreatment count of peripheral neutrophils, monocytes, and lymphocytes as independent prognostic factor in patients with head and neck cancer. Head Neck 2017;39:219–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Han L, Jia Y, Song Q, et al. Prognostic significance of preoperative absolute peripheral monocyte count in esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Dis Esophagus 2016;29:740–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Toyokawa T, Kubo N, Tamura T, et al. The pretreatment Controlling Nutritional Status (CONUT) score is an independent prognostic factor in patients with resectable thoracic esophageal squamous cell carcinoma: results from a retrospective study. BMC Cancer 2016;16:722–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Chan JCY, Chan DL, Diakos CI, et al. The lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio is a superior predictor of overall survival in comparison to established biomarkers of resectable colorectal cancer. Ann Surg 2017;265:539–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Ni XJ, Zhang XL, Ou-Yang QW, et al. An elevated peripheral blood lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratio predicts favorable response and prognosis in locally advanced breast cancer following neoadjuvant chemotherapy. PloS One 2014;9:e111886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Hirahara N, Matsubara T, Kawahara D, et al. Prognostic significance of preoperative inflammatory response biomarkers in patients undergoing curative thoracoscopic esophagectomy for esophageal squamous cell carcinoma. Eur J Surg Oncol 2017;43:493–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Hsu JT, Wang CC, Le PH, et al. Lymphocyte-to-monocyte ratios predict gastric cancer surgical outcomes. J Surg Res 2016;202:284–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cong X, Li S, Xue Y. Impact of preoperative lymphocyte to monocyte ratio on the prognosis of the elderly patients with stage II-III gastric cancer. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi 2016;19:1144–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Tecchio C, Scapini P, Pizzolo G, Cassatella MA. On the cytokines produced by human neutrophils in tumors. Semin Cancer Biol 2013;23:159–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Goubran HA, Stakiw J, Radosevic M, et al. Platelets effects on tumor growth. Semin Oncol 2014;41:359–69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Turri-Zanoni M, Salzano G, Lambertoni A, et al. Prognostic value of pretreatment peripheral blood markers in paranasal sinus cancer: Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio. Head Neck 2017;39:730–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Wang D, Yang JX, Cao DY, et al. Preoperative neutrophil-lymphocyte and platelet-lymphocyte ratios as independent predictors of cervical stromal involvement in surgically treated endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Onco Targets Ther 2013;6:211–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhu Y, Si W, Sun Q, et al. Platelet-lymphocyte ratio acts as an indicator of poor prognosis in patients with breast cancer. Oncotarget 2017;8:1023–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Zou ZY, Liu HL, Ning N, et al. Clinical significance of pre-operative neutrophil lymphocyte ratio and platelet lymphocyte ratio as prognostic factors for patients with colorectal cancer. Oncol Lett 2016;11:2241–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Li S, Xu X, Liang D, et al. Prognostic value of blood neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) and platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio (PLR) in patients with gastric cancer. Zhonghua Zhong Liu Za Zhi 2014;36:910–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Xu L, Zhou X, Wang J, et al. The hematologic markers as prognostic factors in patients with resectable gastric cancer. Cancer Biomark 2016;17:359–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]