Abstract

Objective:

African Americans (AA) are often underrepresented and tend to lose less weight than White participants during the intensive phase of behavioral obesity treatment. Some evidence suggests that AA women experience better maintenance of lost weight than White women, however, additional research on the efficacy of extended care programs (i.e. continued contacts to support the maintenance of lost weight) is necessary to better understand these differences.

Methods:

The influence of race on initial weight loss, the likelihood of achieving ≥5% weight reduction (i.e. extended care eligibility), the maintenance of lost weight and extended care program efficacy was examined in 269 AA and White women (62.1% AA) participating in a 16-month group-based weight management program. Participants achieving ≥5% weight reduction during the intensive phase (16 weekly sessions) were randomized to a clustered campaign extended care program (12 sessions delivered in three, 4-week clusters) or self-directed control.

Results:

In adjusted models, race was not associated with initial weight loss (p = 0.22) or the likelihood of achieving extended care eligibility (odds ratio 0.64, 95% CI [0.29, 1.38]). AA and White women lost −7.13 ± 0.39 kg and −7.62 ± 0.43 kg, respectively, during initial treatment. There were no significant differences in weight regain between AA and White women (p = 0.64) after adjusting for covariates. Clustered campaign program participants (AA: −6.74 ± 0.99 kg, White: −6.89 ± 1.10 kg) regained less weight than control (AA: −5.15 ± 0.99 kg, White: −4.37 ± 1.04 kg), equating to a 2.12 kg (p = 0.03) between-group difference after covariate adjustments.

Conclusions:

Weight changes and extended care eligibility were comparable among all participants. The clustered campaign program was efficacious for AA and White women. The high representation and retention of AA participants may have contributed to these findings.

Keywords: Racial disparities, lifestyle intervention, obesity, weight loss, weight loss maintenance

Introduction

It is well-known that obesity is an epidemic in the United States, and its prevalence is disproportionately higher among African Americans (AA), with AA women experiencing the greatest burden (Ogden et al. 2015). While behavioral weight management interventions typically produce clinically significant weight loss (≥5% reduction in weight) (Butryn, Webb, and Wadden 2011) mounting evidence has demonstrated that treatment efficacy is limited in AAs (Wingo, Carson, and Ard 2014; Lewis, Edwards-Hampton, and Ard 2016; Goode et al. 2017). When exposed to the same behavioral intervention, AA participants typically achieve less long-term weight loss at follow-up than White participants (Kumanyika et al. 1991; West et al. 2007; Fitzgibbon et al. 2012; Davis et al. 2015; Knox-Kazimierczuk and Shockly-Smith 2017), with AA women exhibiting the least amount of overall weight loss compared to AA men and White men and women (West et al. 2008). Trials of weight loss maintenance suggest that the pattern of weight change may vary by race (Rickel et al. 2011). In particular, AA participants achieved less weight loss during initial programs (Hollis et al. 2008; Rickel et al. 2011) but experienced similar or less regain of lost weight during extended maintenance programs compared to Whites (Phelan et al. 2010).

The maintenance of lost weight is a continual challenge in obesity treatment, and the use of extended care programs for the prevention of weight regain has been successful in improving long-term weight outcomes (Middleton, Patidar, and Perri 2012). For those randomized to continued treatment, current knowledge on efficacious extended care programs for AA participants are mixed (Svetkey et al. 2008; Rickel et al. 2011). In the Weight Loss Maintenance (WLM) Trial, for example, weight regain differed by treatment condition (i.e. a personal-contact condition regained less weight than the technology-based condition and self-directed control), but race did not influence treatment responses (Svetkey et al. 2008). In the TOURS weight loss maintenance trial, AA and White women experienced similar regain of lost weight but a significant race-by-treatment interaction showed that White women receiving additional support during extended care (i.e. face-to-face or telephone counseling) regained less weight than White women in the control group. In contrast, the provision of extended care contacts did not attenuate weight regain in AA women (Rickel et al. 2011). Hence, it cannot be assumed that extended care strategies for weight maintenance are equally effective in all race subgroups and there is a need for additional research in this area. It is also important to note that these studies and others (West et al. 2011; Wingo, Carson, and Ard 2014) have relied upon unbalanced samples with less representation from AA participants (38% and 19% AA in WLM and TOURS, respectively) making generalizations challenging (Ojha, Thertulien, and Fischbach 2008). As a result, our knowledge on the efficacy of extended care to support the maintenance of lost weight in AA participants is limited.

Additional research of weight loss maintenance with sufficient representation of AA participants is needed to examine the influence of race on the eligibility and impact of extended care maintenance programs and to identify efficacious approaches to enhance the maintenance of lost weight for a diversity of individuals, including AA women. These efforts are needed to develop adequate obesity treatments for AA women and reduce the racial gap in obesity and related disparities. The Improving Weight Loss (ImWeL) trial (Dutton et al. 2017) can address this issue, as it consists of a racially- inclusive sample (62% AA) participating in a 16-month randomized weight management trial. Following an initial, 4-month intensive weight loss program, participants achieving ≥5% weight reduction were randomized to a 12-month extended care program to promote maintenance of lost weight. Thus, the ImWeL trial presents an opportunity to examine the influence of race on initial weight loss and eligibility for extended care as well as the maintenance of lost weight and the efficacy of extended care for AA women.

Methods

Sample

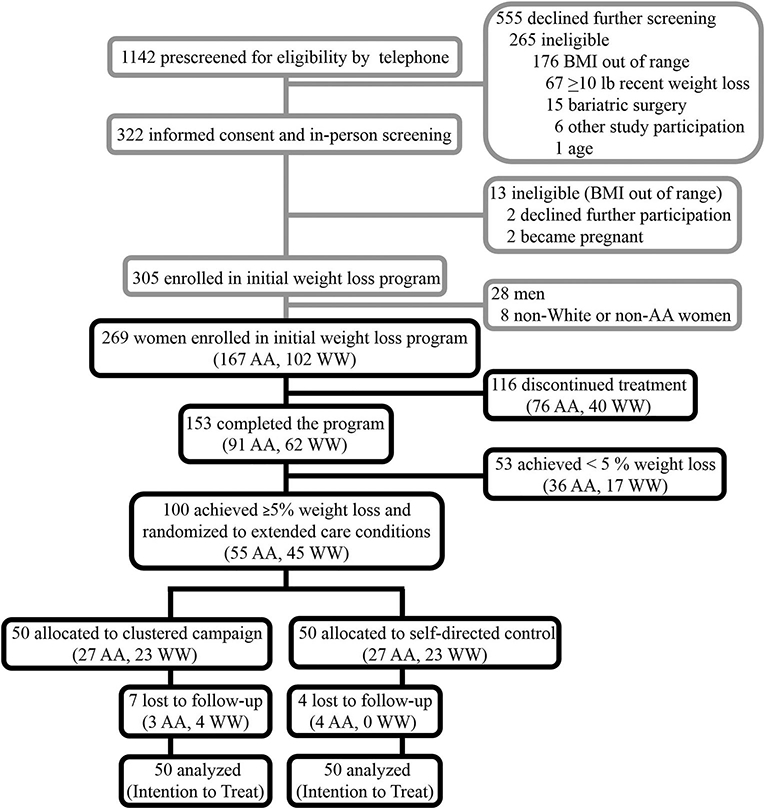

A detailed description of the ImWeL trial can be found elsewhere (Dutton et al. 2017). Briefly, adults (≥21 years-old) with a body mass index (BMI; kg/m2) between 28 and 45 were eligible to participate. Participants were excluded for the following reasons: weight loss >4.5 kg and/or use of a weight loss medication in the past six months, medical condition for which weight loss or physical activity would be inadvisable(i.e. uncontrolled diabetes, myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident, or unstable angina within the past six months), plans to relocate from the area in the next 18 months, unable or unwilling to attend sessions, or unwilling to accept random assignment. Recruitment avenues included local newspaper advertisements, announcements on local television morning programs, flyers posted in local primary care clinics, and university-affiliated websites and e-newsletters. The ImWeL trial initially enrolled 305 participants (95.4% female, 54.6% minority). From this sample, there were 28 men and 8 non-white or non-AA minority participants who were not included in the present analyses, since the current focus was on weight outcomes for AA and White women. Therefore, this investigation included data from 269 AA and White women (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram. The upper grayscale portion of the diagram was adapted from the primary ImWeL findings (Dutton et al. 2017). The lower black portion reflects the enrollment and allocation for the present study.

Procedures

The initial weight loss program (months 0–4) consisted of weekly, group-based sessions (12–18 participants per group) that included training on behavioral strategies (e.g. goal setting, problem solving, self-monitoring) and recommendations for caloric restriction (1200 or 1500 kcals/day for participants weighing <250 pounds or ≥250 pounds, respectively), and physical activity (≥180 minutes/week) (Dutton et al. 2017). During this phase, participants were encouraged to achieve a ≥5% weight reduction and were aware that this criterion was a requirement to continue into the extended care phase. Following completion of the initial phase, participants attended an assessment visit (month 4), and those deemed eligible (i.e. ≥5% weight loss) were randomized (using block sizes of 4 to maintain balance) to either one of two 12-month extended care programs (months 4–16): Program 1) 12 temporally-clustered in-person group contacts delivered in three, 4-week clusters (at months 7, 10, 13) that were separated by extended periods without contact (i.e. ‘clustered campaign’), or Program 2) a self-directed control group that received the same print-based intervention materials but no additional in-person contact (i.e. ‘self-directed’) (Dutton et al. 2017). The participating academic health center’s Institutional Review Board approved the protocol and informed consent was obtained prior to study participation. The trial was registered with clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02487121).

Measures

Demographics and anthropometrics.

Age, race, educational attainment, income, and marital status were self-reported by participants at baseline. Trained staff not directly involved in the delivery of treatment measured participants’ height and weight. Height was measured at baseline to the nearest 0.1 cm using a wall-mounted stadiometer. Weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kg using a calibrated digital scale at 0, 4, and 16 months.

Attendance.

Session attendance was assessed through participant weigh-ins at each group session (initial phase: 16 sessions for all participants; extended care phase: 12 sessions for the clustered campaign group only).

Statistical analyses

Summary statistics (means, proportions, and standard deviations) for sample characteristics were calculated. For bivariate comparisons between AA and Whites, t-tests and Chi-square tests were performed. To examine racial differences in weight loss outcomes and attendance, multiple linear regression and multiple logistic regression models were fitted, parameter estimates and p-values were obtained. For the initial program (months 0–4), in addition to race (reference: White), predictor variables included treatment (reference: self-directed), age, marital status (reference: married), income (reference: under $40,000 k), initial weight, and attendance. For the extended care phase (months 4–16), the predictor variables included in the models were race, treatment, age, marital status, education level (reference: associates degree or lower), and weight at month 4. By design, attendance for the extended care phase was only available for the treatment group. A treatment by race interaction was used to examine whether treatment effects differed by race. Intention-to-treat analyses were used and missing values for month 16 weight were imputed using multiple imputation (Elobeid et al. 2009). The model fit for session attendance was not based on multiple imputation. To assess the overall effect of the weight management trial from month 0 to month 16, a mixed effects model with unstructured covariance was utilized. In addition to age, marital status, and education, variables in this model included race, treatment, potential racial difference in the treatment effect and their interactions with time. Data were analyzed using R 3.2.3 and SAS 9.4 software (SAS institute, Cary, NC) and significance was set at p < 0.05.

Results

Initial phase of treatment

Baseline participants’ characteristics, session attendance, and program completion

Of the 269 women initially enrolled in the weight loss program, 167 (62.1%) were AA and 102 (37.9%) were White (Figure 1). Significant differences in age, marital status, and income were observed by race, as AA participants tended to be younger, less likely to be married, and had lower income Table 1, left panel). After adjusting for relevant covariates, attendance during the initial weight loss program was not significantly different between initially enrolled AA and White women (mean[SE]: 0.05[0.67], p = 0.94). In the adjusted logistic regression model, completion of the initial program was not significantly different between AA and White women (odds ratio (OR) 0.78, 95% CI [0.27, 2.22], p = 0.64). Of the 269 initial enrollees, 153 (56.9%) women completed the initial treatment, 91 (59.5%) were AA and 62 (40.5%) were White, representing 54% (91 of 167) and 61% (62 of 102) of those initially enrolled, respectively (Figure 1). On average, these participants attended ([unadjusted] mean ± standard deviation) 12.4 ± 3.0 of the initial 16 sessions (AA: 12.2 ± 3.1, White: 12.6 ± 2.9). In the adjusted linear regression model, treatment session attendance for these individuals did not differ by race (mean[SE]: −0.05[0.53], p = 0.92).

Table 1.

Sample characteristics.

| Characteristic | Baseline Sample | Randomized Sample | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| African Americans | White Women | P-valuea | Total | African Americans | White Women | P-valuea | Total | |

| Race, No. (%) | - | - | NA | 269 | - | - | NA | 100 |

| African American | 167 | - | 167 | 55 | - | 55 | ||

| White | - | 102 | 102 | - | 45 | 45 | ||

| Age, years | 45.42 (10.93) | 52.05 (12.93) | <.0001 | 47.93 (12.14) | 46.60 (11.99) | 57.53 (10.67) | <.0001 | 51.52 (12.61) |

| Body weight, kg | 96.47 (16.69) | 95.45 (15.24) | 0.6150 | 96.08 (16.13) | 92.79 (14.26) | 91.03 (11.76) | 0.5082 | 92.00 (13.16) |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 36.15 (4.50) | 35.46 (4.66) | 0.2334 | 35.89 (4.57) | 35.62 (4.30) | 34.70 (4.12) | 0.2816 | 35.21 (4.22) |

| Marital status, No. (%) | 0.0066 | 0.0946 | ||||||

| Not Married | 94 (56.29) | 40 (39.22) | 134 | 30 (54.55) | 17 (37.78) | 47 | ||

| Married | 73 (43.71) | 62 (60.78) | 135 | 25 (45.45) | 28 (62.22) | 53 | ||

| Education, No. (%) | 0.3597 | 0.8529 | ||||||

| Associates or lower degree | 75 (44.91) | 40 (39.22) | 115 | 21 (38.18) | 18 (40.00) | 39 | ||

| Bachelors or higher degree | 92 (55.09) | 62 (60.78) | 154 | 34 (61.82) | 27 (60.00) | 61 | ||

| Income, No. (%) | 0.0062 | 0.4202 | ||||||

| <$40,000 | 68 (40.72) | 25 (24.51) | 93 | 18 (32.73) | 13 (28.89) | 31 | ||

| $40,000-$80,000 | 66 (39.52) | 42 (41.18) | 108 | 24 (43.64) | 16 (35.56) | 40 | ||

| >$80,000 | 33 (19.76) | 35 (34.31) | 68 | 13 (23.64) | 16 (35.56) | 29 | ||

Abbreviations: BMI = body mass index. Data are given as mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated. All values are at the start of the initial weight loss program (i.e. month 0).

P-values are calculated for continuous variables using T-test and calculated for categorical variables using Chi-square Test or Fisher’s exact test to compare between groups.

Initial weight loss and extended care eligibility

For those completing the initial program, race was not associated with initial weight loss at month 4 after adjusting for covariates (0.77[0.62] kg, p = 0.22). Similarly, race was not associated with the likelihood of achieving ≥5% weight loss during the initial program (i.e. extended care eligibility) (OR 0.64, 95% CI [0.29, 1.38], p = 0.25).

Extended care phase of treatment

Randomized participants’ characteristics and session attendance

After the initial program, 100 of 153 (65.4%) participants met the criteria for extended care (≥5% weight loss). This included 55 AA women and 45 White women (60.4% (55 of 91) and 72.6% (45 of 62) completing the initial program, respectively). From the initially enrolled sample, this represents 33% (55 of 167) of AA women and 44% (45 of 102) of White women being eligible for extended care. Baseline characteristics of the participants randomized to extended care are summarized in Table 1 (right panel). Age was the only significant between-race difference, with AA women being younger than White women. Participants attended ([unadjusted] mean ± standard deviation) 9.3 ± 2.4 of the 12 extended care sessions (AA: 9.8 ± 2.1, White: 8.7 ± 2.5). In the multiple linear regression model, treatment session attendance during extended care was not significantly different between AA and White women (1.40[0.76], p = 0.08).

Weight regain during the extended care period

Overall, participants randomized to the clustered campaign treatment group regained less weight than participants in the self-directed control group (−2.12[0.95] kg, p = 0.03) (Table 2, top panel). In the adjusted linear regression model, there were no differences in weight regain between AA and White women (−0.51[1.08] kg, p = 0.64). An interaction term was applied to the model to examine whether the significant treatment effect varied by race. The interaction term was not significant (Table 2, bottom panel) indicating that the treatment effect did not differ by race, and the treatment effect was attenuated (p = 0.06; Table 2, bottom panel). The lack of a significant interaction term indicates its removal from the model provides a more accurate estimate of effects (Table 2, top panel). Similarly, in the adjusted logistic regression model, there were no significant racial differences in the likelihood of maintaining ≥5% reductions from baseline weight at month 16 (OR 1.25, 95% CI [0.47, 3.30], p = 0.65). However, the treatment effect was no longer significant in this model (OR 1.49, 95% CI [0.63, 3.53], p = 0.37) indicating that, in the randomized sample the likelihood of maintaining ≥5% weight loss at month 16 was not different between the two extended care conditions.

Table 2.

Linear regression analysis of weight changes during the extended carea.

| Variablesb | Estimate | SE | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Without Interaction | |||

| Race | −0.505 | 1.08 | 0.64 |

| Treatment | −2.123 | 0.95 | 0.03 |

| Weight at month 4 | −0.039 | 0.04 | 0.32 |

| Age | −0.004 | 0.04 | 0.93 |

| Marital Status | −1.233 | 0.97 | 0.21 |

| Education | −0.379 | 0.99 | 0.70 |

| With Race*Treatment Interaction | |||

| Race | −1.016 | 1.42 | 0.48 |

| Treatment | −2.675 | 1.40 | 0.06 |

| Race*Treatment | 1.008 | 1.87 | 0.59 |

| Weight at month 4 | −0.042 | 0.04 | 0.29 |

| Age | −0.005 | 0.04 | 0.91 |

| Marital Status | −1.233 | 0.98 | 0.21 |

| Education | −0.379 | 0.99 | 0.70 |

Analyses are based on multiple imputation of missing data.

Comparison versus reference groups for the categorical variables are as follows: Race (African American vs. White), Treatment (Clustered Campaign vs. Self-directed), Marital Status (Not-married vs. Married), Education (Bachelors or higher degree vs. Associates or lower degree).

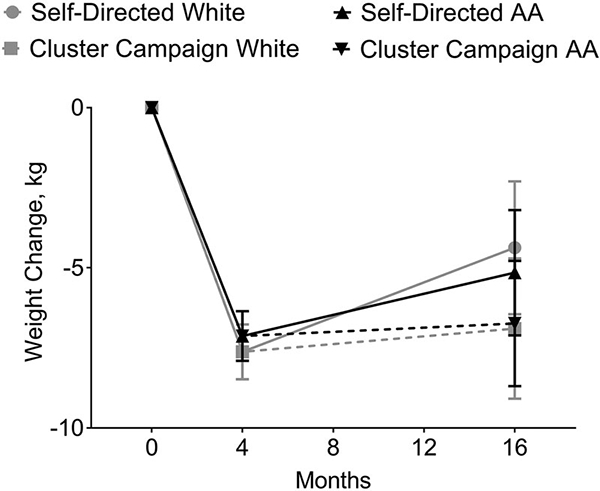

Overall effects (initial + extended care phases of treatment)

In the overall pattern model with unstructured covariance, race did not significantly affect weight loss or weight regain over time (F(3,95) = 0.70, p = 0.55). The patterns of weight change by race, with age equal to the mean and all other covariates at the reference levels, are displayed in Figure 2. At Month 4, the mean weight change from baseline for AA and White women were −7.13[0.39] kg, 95% CI [−7.90, −6.35] and −7.62[0.43] kg, 95% CI [−8.48, −6.76], respectively. There were no racial differences in weight change at month 16 within either the clustered campaign treatment (AA: −6.74[0.99] kg, 95% CI [−8.69, −4.78], Whites: −6.89[1.10] kg, 95% CI [−9.08, −4.71]) or self-directed control groups (AA: −5.15[0.99] kg, 95% CI [−7.11, −3.20], Whites: −4.37 [1.04] kg, 95% CI [−6.44, −2.30]).

Figure 2.

Overall weight change pattern from Months 0–16. Values are mean weight change over time with 95% confidence intervals.

Discussion

In this weight loss maintenance trial that included an initial 4-month weight loss phase followed by randomization into a 12-month extended care program, AA and White women experienced similar weight changes throughout the trial. Specifically, initial weight loss, the proportion of participants qualifying for extended care (i.e. initially achieving ≥5% weight loss), and weight regain during extended care were comparable in AA and White women. Also, AA and White women engaged in treatment at similar levels in terms of the number of treatment sessions attended and their likelihood of completing the program. Moreover, participants in the clustered campaign extended care group regained less weight than self-directed control participants regardless of race.

The initial weight loss phase of the ImWeL trial was modeled after the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) (Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group 2002) (i.e. 16 core sessions with caloric restriction and physical activity recommendations) but utilized a shorter program duration and lower, although clinically significant, weight loss goal (ImWeL: ≥5% weight loss in 4 months; DPP: ≥7% weight loss in 6 months). The lifestyle component of the original DPP (West et al. 2008) and subsequent translations of this program (Samuel-Hodge et al. 2014) have shown that AA women achieved less weight loss than other race and sex groups, including White women, during the initial phase of treatment. However, our data contrast previous findings as both AA and White women achieved similar weight loss. In the study examining the effectiveness of DPP translations among AAs, it was suggested that low treatment attendance (for all participants in the AA-only and mixed race groups) may partially explain the attenuated weight loss (Samuel-Hodge et al. 2014). Others demonstrating low attendance from AA participants and less weight loss, relative to Whites, lends support for this rationale (Hollis et al. 2008; Davis et al. 2015) and may explain the lack of racial differences in initial weight loss in the current study, since attendance levels were high (75%) and similar across racial groups.

Thirty-seven percent of those initially enrolled at baseline lost sufficient weight to qualify for extended care and, interestingly, AA women made up most (55%) of this sample. Recently, it has been recommended that researchers consider extending the initial phase of maintenance trials or reduce the weight loss criterion for certain racial subgroups given data demonstrating racial disparities in achieving adequate weight loss (Voils et al. 2016). However, findings of the current study suggest that this may not be as important and, perhaps, focusing on identifying strategies to enhance program attendance, and therefore treatment dose, among AA participants during the weight loss phase may be more important for their success. One of these strategies may be to oversample AA participants. Since AA participants are commonly underrepresented in behavioral obesity treatment (Ojha, Thertulien, and Fischbach 2008), and AA women in the ImWeL trial made up more than half of the participants in the weight loss program (62% of baseline sample and 55% of the randomized sample), it is possible that the high proportion of AA in the study may have contributed to the high attendance rates and subsequent similarities in weight loss and extended care eligibility. A previous study examining the effect of group racial composition on weight loss in AA found no difference in session attendance or weight loss between groups with only AA participants compared to groups consisting of mixed races (Ard et al. 2008) and suggested that one factor contributing to these findings was the high proportion (>50%) of AA in the mixed-race groups. These authors hypothesized that the high proportion of AA in mixed-race groups may have altered the group dynamic in a manner similar to that of groups comprised exclusively of AAs (Ard et al. 2008).

Previous studies have demonstrated that AA participants are better able to maintain initial weight losses and that continued support following initial weight loss may not provide additional benefits for AA women compared to White women (West et al. 2007; Rickel et al. 2011; Wingo, Carson, and Ard 2014). However, not all studies support a differential effect of race in extended care programs (Svetkey et al. 2008). For example, Rickel et al. found that biweekly extended care support through phone or face-to-face group counseling improved the maintenance of lost weight in White women, but these contacts did not improve long-term outcomes for AA women when compared to an educational control condition (Rickel et al. 2011). In contrast, Svetkey et al. showed that race did not differentially influence the treatment effects observed in the WLM trial (Svetkey et al. 2008). Noteworthy, in previous studies using extended care contacts for the maintenance of lost weight AA participants have been underrepresented due to low study enrollment and/or excluded due to insufficient initial weight loss (Svetkey et al. 2008; Rickel et al. 2011; Wingo, Carson, and Ard 2014; Voils et al. 2016). Consequently, there are limited data to inform the development of efficacious obesity treatment programs for this population.

An important aspect of the current study is that AA women were well represented in the maintenance program allowing us to examine the utility of a clustered campaign extended care approach to prevent the regain of lost weight for a population experiencing the greatest obesity burden. Thus, our findings make an important contribution to current knowledge in the field of behavioral obesity treatment for AA women. Tussing-Humphreys and colleagues noted in their systematic review of behavioral obesity treatments for AA women that the most effective interventions were those that included a formal maintenance program, identified weight loss as the primary outcome and incorporated cultural adaptations and tailoring (Tussing-Humphreys et al. 2013). Recent reviews on the role of cultural adaptations to enhance obesity treatment for AA participants are mixed (Burton, White, and Knowlden 2017; Knox-Kazimierczuk and Shockly-Smith 2017). In the ImWeL Trial, AA women receiving extended care experienced similar weight outcomes to White women throughout the intervention despite the lack of formal tailoring and cultural adaptations. While these findings fail to support the need for culturally tailored intervention content, it is likely that the high proportion of AA participants retained in our trial had some unintended consequences related to tailoring and perceptions of relevance and may in fact be the only cultural adaptation required. Further investigation is necessary given the mixed findings on this topic to-date.

The most notable strength of this study is the high recruitment and retention of a racially balanced, representative sample of AA women, a noted limitation of previous work (Rickel et al. 2011; Wingo, Carson, and Ard 2014). This not only improves the generalizability of the findings but also provides preliminary evidence to strengthen the inferences about the initial and extended treatment efficacy for these individuals (Ojha, Thertulien, and Fischbach 2008). The fact that the initial phase of treatment was only 4 months, yet still sufficient to promote comparable weight loss amongst the AA and White participants may be due to the high proportion of AAs involved in the study and potential alterations in the group environment (Ard et al. 2008) and subsequent program engagement, as mentioned previously. It is also possible that the relatively high levels of education and income in our sample afforded the participants access to resources allowing them to engage in treatment at a sufficient and equivalent intensity. Additionally, there was a relatively lower completion rate for the initial study which may suggest that our participant sample may be highly selective and could potentially wash out racial differences identified in other samples (Rickel et al. 2011).

This study is not without limitations. First, the original trial (Dutton et al. 2017) was not specifically powered to examine racial differences in treatment response, and the sample size may have limited our ability to detect significant differences between AA and White participants. For these reasons, our findings suggesting no racial differences in weight loss and maintenance should be interpreted with caution as it may have been underpowered to detect potential differences. Additionally, AA women in the sample were ~10 years younger than White women, and it is unknown whether this age difference contributed to the current findings. Whether a similar treatment response would be observed in racially-diverse, age-matched women is a topic for future exploration. Lastly, the influence of physical activity and dietary adherence on the outcomes of interest were not assessed in the present study.

Contrary to previous findings, the present study demonstrates comparable levels of initial weight loss and long-term maintenance among AA and White women participating in a 16-month weight management trial. The clustered campaign extended care program improved the maintenance of weight loss in both AA and White women. Replicating the current findings with a larger participant sample that includes other racial minority groups and greater representation of men may be warranted. The success of this weight management trial may, in part, be due to the high treatment engagement (i.e. session attendance) from our participants and the lack of racial differences may be attributed to the high retention of AA women throughout the trial. As minorities are often underrepresented in lifestyle interventions, future studies should focus on enhancing recruitment and retention efforts to ensure that the sample size and representation from AA are sufficient throughout maintenance trials to better optimize behavioral obesity treatments for this population.

Key messages.

This study utilized similar proportions of AA and White participants, overcoming a noted limitation of previous work in this area.

Initial weight loss and likelihood of achieving ≥5% weight reduction (i.e. eligibility for the extended care program) was similar among AA and White women.

The extended care intervention improved the maintenance of lost weight and had comparable effects in AA and White women.

Funding

This work was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases [grant number K23DK081607, T32DK062710].

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to report. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Diabetes And Digestive And Kidney Diseases or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Affuso O, Kaiser KA, Carson TL, Ingram KH, Schwiers M, Robertson H, Abbas F, and Allison DB. 2014. “Association of Run-in Periods with Weight Loss in Obesity Randomized Controlled Trials.” Obesity Reviews 15 (1): 68–73. doi: 10.1111/obr.12111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ard Jamy D., Kumanyika S, Stevens VJ, Vollmer WM, Samuel-Hodge C, Kennedy B, Gayles D, et al. 2008. “Effect of Group Racial Composition on Weight Loss in African Americans.” Obesity 16 (2): 306–310. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton WM, White AN, and Knowlden AP. 2017. “A Systematic Review of Culturally Tailored Obesity Interventions among African American Adults.” American Journal of Health Education 48 (3): 185–197. doi: 10.1080/19325037.2017.1292876. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Butryn ML, Webb V, and Wadden TA. 2011. “Behavioral Treatment of Obesity.” Psychiatric Clinics of North America 34 (4): 841–859. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis KK, Tate DF, Lang W, Neiberg RH, Polzien K, Rickman AD, Erickson K, and Jakicic JM. 2015. “Racial Differences in Weight Loss Among Adults in a Behavioral Weight Loss Intervention: Role of Diet and Physical Activity.” Journal of Physical Activity and Health 12(12): 1558–1566. doi: 10.1123/jpah.2014-0243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP) Research Group. 2002. “The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): Description of Lifestyle Intervention.” Diabetes Care 25 (12): 2165–2171. http://www. ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12453955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutton GR, Gowey MA, Tan F, Zhou D, Ard J, Perri MG, Lewis CE, et al. 2017. “Comparison of an Alternative Schedule of Extended Care Contacts to a Self-Directed Control: A Randomized Trial of Weight Loss Maintenance.” International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 14 (1): 2985–3023. doi: 10.1016/J.JACC.2013.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elobeid MA, Padilla MA, McVie T, Thomas O, Brock DW, Musser B, Lu K, et al. 2009. “Missing Data in Randomized Clinical Trials for Weight Loss: Scope of the Problem, State of the Field, and Performance of Statistical Methods.” PLoS ONE 4 (8): e6624. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzgibbon ML, Tussing-Humphreys LM, Porter JS, Martin IK, Odoms-Young A, and Sharp LK. 2012. “Weight Loss and African-American Women: A Systematic Review of the Behavioural Weight Loss Intervention Literature.” Obesity Reviews 13 (3): 193–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00945.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goode RW, Styn MA, Mendez DD, and Gary-Webb TL. 2017. “African Americans in Standard Behavioral Treatment for Obesity, 2001–2015: What Have We Learned?” Western Journal of Nursing Research 39 (8): 1045–1069. doi: 10.1177/0193945917692115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollis JF, Gullion CM, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, Appel LJ, Ard JD, Champagne CM, et al. 2008. “Weight Loss During the Intensive Intervention Phase of the Weight-Loss Maintenance Trial.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 35 (2): 118–126. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2008.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knox-Kazimierczuk F, and Shockly-Smith M. 2017. “African American Women and the Obesity Epidemic: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Pan African Studies 10 (1): 76–101. https://www.questia.com/library/journal/1G1-498734465/african-american-women-and-the-obesity-epidemic-a. [Google Scholar]

- Kumanyika SK, Obarzanek E, Stevens VJ, Hebert PR, and Whelton PK. 1991. “Weight-Loss Experience of Black and White Participants in NHLBI-Sponsored Clinical Trials.” The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition 53 (6): 1631S–1638S. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2031498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis KH, Edwards-Hampton SA, and Ard JD. 2016. “Disparities in Treatment Uptake and Outcomes of Patients with Obesity in the USA.” Current Obesity Reports 5 (2): 282–290. doi: 10.1007/s13679-016-0211-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean PS, Wing RR, Davidson T, Epstein L, Goodpaster B, Hall KD, Levin BE, et al. 2015. “NIH Working Group Report: Innovative Research to Improve Maintenance of Weight Loss.” Obesity 23 (1): 7–15. doi: 10.1002/oby.20967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton KM, Patidar SM, and Perri MG. 2012. “The Impact of Extended Care on the Long-Term Maintenance of Weight Loss: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Obesity Reviews 13 (6): 509–517. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2011.00972.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, and Flegal KM. 2015. “Prevalence of Obesity Among Adults and Youth: United States, 2011–2014.” NCHS Data Brief 219 (November): 1–8. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26633046. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ojha R, Thertulien R, and Fischbach L. 2008. “Racial Under-Representation in Clinical Trials: Consequence, Myth, and Proposition.” Epidemiological Focus 1 (1): e2. http://health-equity.lib.umd.edu/1271/1/OjhaEpiFocus2008.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Phelan S, Wing RR, Loria CM, Kim Y, and Lewis CE. 2010. “Prevalence and Predictors of Weight-Loss Maintenance in a Biracial Cohort Results From the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults Study.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 39 (6): 546–554. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2010.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rickel KA, Milsom VA, Ross KM, Hoover VJ, Peterson ND, and Perri MG. 2011. “Differential Response of African American and Caucasian Women to Extended-Care Programs for Obesity Management.” Ethnicity & Disease 21 (2): 170–175. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3772655/. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuel-Hodge CD, Johnson CM, Braxton DF, and Lackey M. 2014. “Effectiveness of Diabetes Prevention Program Translations among African Americans.” Obesity Reviews 15 (S4): 107–124. doi: 10.1111/obr.12211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, Appel LJ, Hollis JF, Loria CM, Vollmer WM, et al. 2008. “Comparison of Strategies for Sustaining Weight Loss: The Weight Loss Maintenance Randomized Controlled Trial.” JAMA 299 (10): 1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tussing-Humphreys LM, Fitzgibbon ML, Kong A, and Odoms-Young A. 2013. “Weight Loss Maintenance in African American Women: A Systematic Review of the Behavioral Lifestyle Intervention Literature.” Journal of Obesity 2013: 1–31. doi: 10.1155/2013/437369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voils CI, Gierisch JM, Olsen MK, Maciejewski ML, Grubber J, McVay MA, Strauss JL, et al. 2014. “Study Design and Protocol for a Theory-Based Behavioral Intervention Focusing on Maintenance of Weight Loss: The Maintenance After Initiation of Nutrition TrAINing (MAINTAIN) Study.” Contemporary Clinical Trials 39 (1): 95–105. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2014.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voils CI, Grubber JM, McVay MA, Olsen MK, Bolton J, Gierisch JM, Taylor SS, Maciejewski ML, and Yancy WS. 2016. “Recruitment and Retention for a Weight Loss Maintenance Trial Involving Weight Loss Prior to Randomization.” Obesity Science & Practice 2 (4): 355–365. doi: 10.1002/osp4.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West DS, DiLillo V, Bursac Z, Gore SA, and Green PG. 2007. “Motivational Interviewing Improves Weight Loss in Women with Type 2 Diabetes.” Diabetes Care 30 (5): 1081–1087. doi: 10.2337/dc06-1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West DS, Gorin AA, Subak LL, Foster G, Bragg C, Hecht J, Schembri M, Wing RR, Diet and Exercise (PRIDE) Research Group. 2011. “A Motivation-Focused Weight Loss Maintenance Program Is an Effective Alternative to a Skill-Based Approach.” International Journal of Obesity (2005) 35 (2): 259–269. 10.1038/ijo.2010.138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West DS, Prewitt TE, Bursac Z, and Felix HC. 2008. “Weight Loss of Black, White, and Hispanic Men and Women in the Diabetes Prevention Program.” Obesity 16 (6): 1413–1420. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wing RR, Hamman RF, Bray GA, Delahanty L, Edelstein SL, Hill JO, Horton ES, et al. 2004. “Achieving Weight and Activity Goals among Diabetes Prevention Program Lifestyle Participants.” Obesity Research 12 (9): 1426–1434. doi: 10.1038/oby.2004.179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wingo BC, Carson TL, and Ard J. 2014. “Differences in Weight Loss and Health Outcomes among African Americans and Whites in Multicentre Trials.” Obesity Reviews 15 (4): 46–61. doi: 10.1111/obr.12212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]