Abstract

Originally identified as the third subunit of the high-affinity IL-2 receptor complex, the common γ-chain (γc) also acts as a non-redundant receptor subunit for a series of other cytokines, collectively known as γc family cytokines. γc plays essential roles in T cell development and differentiation, so that understanding the molecular basis of its signaling and regulation is a critical issue in T cell immunology. Unlike most other cytokine receptors, γc is thought to be constitutively expressed and limited in its function to the assembly of high-affinity cytokine receptors. Surprisingly, recent studies reported a series of findings that unseat γc as a simple housekeeping gene, and unveiled γc as a new regulatory molecule in T cell activation and differentiation. Cytokine-independent binding of γc to other cytokine receptor subunits suggested a pre-association model of γc with proprietary cytokine receptors. Also, identification of a γc splice isoform revealed expression of soluble γc proteins (sγc). sγc directly interacted with surface IL-2Rβ to suppress IL-2 signaling and to promote pro-inflammatory Th17 cell differentiation. As a result, endogenously produced sγc exacerbated autoimmune inflammatory disease, while the removal of endogenous sγc significantly ameliorated disease outcome. These data provide new insights into the role of both membrane and soluble γc in cytokine signaling, and open new venues to interfere and modulate γc signaling during immune activation. These unexpected discoveries further underscore the perspective that γc biology remains largely uncharted territory that invites further exploration.

Keywords: Alternative splicing, JAK3, Homeostasis, Signaling, Survival

Introduction

The γc cytokine receptor is the shared receptor subunit for the cytokines IL-2, IL-4, IL-7, IL-9, IL-15 and IL-21, which are collectively referred to as γc cytokines [1]. Members of the γc cytokine family play distinct and non-redundant roles in the adaptive immune system, and especially in the development and differentiation of T lymphocytes. The importance of γc in the immune system is illustrated by the profound phenotype associated with γc gene deficiency that manifests as T-, NK cell deficiency in humans and as T-, B-, NK cell deficiency in mice [2]. Thus, γc expression is a non-redundant requirement for lymphocytes, and especially critical for T cells in both humans and mice.

γc is the only cytokine receptor that is encoded in the X chromosome. Because γc is subject to X chromosome inactivation, γc shows monoallelic expression and provides the genetic explanation for X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency (X-SCID) [3]. Accordingly, male carriers of γc mutations are immunodeficient, while female carriers of γc mutations are immunocompetent. X chromosome inactivation is a stochastic event, so that both γc-expressing and non-expressing T cells should exist in heterozygotic carriers. However, in female obligate carriers, all T cells had selectively inactivated the X chromosome with the X-SCID allele [4]. This is in contrast to T cells from normal females which show patterns of random X chromosome inactivation. Thus, X chromosome inactivation in T cells of X-SCID carriers is non-random and only T cells expressing functional γc protein develop and survive [5].

Because γc is required for signaling by all γc cytokines, immunodeficiency of γc−/− mice could have been the result of a compound effect equivalent to multiple γc cytokine deficiencies. Alternatively, immunodeficiency could have resulted from impaired signaling by a single γc cytokine. Gene targeting studies of γc cytokines revealed that most γc cytokine deficiencies did not affect T cell development or T cell survival [1, 6]. However, IL-7 was unique among γc cytokines as IL-7 deficiency alone was sufficient to phenocopy the immunodeficiency associated with γc ablation [7]. These results suggested that—at least for T cell development and survival—γc is necessary because it is required for IL-7 signaling. Thus, γc expression is a non-redundant requirement for T cells, and γc is critical for T cell development because of its role in IL-7 signaling.

While IL-7 is the first γc cytokine requirement that immature thymocytes encounter during their development in the thymus [7–10], γc cytokines other than IL-7 also play critical roles in T cell development, although at later stages. As such, IL-2 signaling is important for Foxp3+ regulatory T cell development [11], and IL-4 signaling plays a critical role in the development of eomesodermin+ innate CD8 T cells in the thymus [12]. Furthermore, IL-15 signaling is necessary for memory T cell differentiation [13, 14], while IL-21 signaling promotes development of effector CD4 T cells, such as follicular helper T cells and IL-17-producing Th17 cells [15–17]. Collectively, individual γc cytokines play distinct and non-redundant roles in T cell development and differentiation, and they all require γc for high-affinity cytokine binding and signaling. Hence, understanding the mechanism how γc is promiscuous enough to interact with different γc cytokines and their proprietary receptors, yet also specific enough to interact only with γc family members, has fascinated immunologists for decades.

Despite its importance in T cell biology, surprisingly little information is available concerning how γc expression is regulated and how γc signaling is controlled. Along these lines, no transcription factor has yet been identified to control γc expression in T cells. In fact, it is unclear if transcriptional mechanisms even do exist to regulate γc expression. Moreover, the mechanism of high-affinity cytokine receptors assembly by γc and proprietary cytokine receptors needs further refinements. Also, how γc triggers both unique and shared downstream effector signals by distinct γc cytokine receptors remains poorly understood. Thus, interrogating the biology of γc expression and signaling remains a nascent field.

Fortunately, significant strides have been made regarding the molecular aspects of γc regulation. Recent studies uncovered a post-transcriptional mechanism to regulate γc expression [18], structural investigations provided new insights into γc cytokine receptor assembly [19], and a series of biochemical studies shed new light on the mechanistic aspects of γc signaling [20, 21]. Collectively, these observations allow us to revise and refine our perspective of γc function and expression. In this review, we will recount these recent advances and discuss their implications in context of γc’s role in controlling T cell immunity.

A non-redundant role for γc in T cell development

Among all cytokine receptors, none has such a profound and broad effect on the adaptive immune system as the γc cytokine receptor. γc cytokine signals provide pro-survival cues, inhibit pro-apoptotic signals, upregulate metabolic activities and promote expression of select transcription factors, which determine lineage fate and maturation of lymphocyte subsets [1, 22]. The essential role of γc in T cell development was established by Leonard and colleagues [3], who discovered that the γc gene was localized to chromosome Xq13 in the region previously associated with X-SCID [23, 24]. Using multipoint linkage analysis and recombinant breakpoint analysis, the authors identified γc as the elusive X-SCID gene. Moreover, they demonstrated that all three of the X-SCID patients in their study carried point mutations in the γc gene that resulted in generation of pre-mature stop codons and the failure to produce functional γc proteins [3]. The association of γc gene deficiency and X-SCID was further verified in an independent study by Puck and colleagues with four unrelated X-SCID patients [25]. Altogether, these results suggested a causal relationship between γc deficiency and X-SCID, and proposed a non-redundant role for γc in T cell development.

To directly demonstrate γc deficiency as the genetic cause of X-SCID, γc expression was ablated in two different mouse models. The first γc-deficient mouse was generated by Rajewsky and colleagues using the Cre/loxP strategy and by deleting a genomic region of γc that spanned exons 2–6. This region corresponds to most of the extracellular domain and the transmembrane domain of γc [5]. Leonard and colleagues, on the other hand, generated a γc-deficient mouse where a part of exon 3 and all of exons 4–8 were replaced with a neomycin cassette, resulting in deletion of the majority of the extracellular domain and the entire transmembrane domain [26]. In both cases, the lack of γc protein expression severely impaired T- and B cell development, resulting in a hypoplastic thymus and very few mature lymphocytes in the periphery. Notably, γc-deficiency in mice resulted in T-, B-, NK-cell deficiency, which contrasts to the T−B+NK− phenotype observed in human SCID patients. Why γc deficiency ablates murine B cell development but results in normal numbers of dysfunctional human B cells is not clear and remains to be resolved [5, 26–28]. Nonetheless, these results established a causal relationship between γc loss of function and X-SCID.

Beyond illustrating the molecular basis of human X-SCID, γc-deficient mice also represented an excellent opportunity to understand the impact of γc on lymphocyte development in further details. γc-deficient mice produced very small numbers of mature αβ T cells and virtually no γδ T cells and NK cells [5, 26]. Interestingly, gut intraepithelial αβ T cell numbers were also dramatically reduced, which is now understood as a consequence of deficiency in IL-15 signaling [13, 29]. Secondary lymphoid organ development was also affected, so that γc-deficient mice lacked Peyer’s patches and were defective in lymph node organogenesis [5]. Notably, thymopoiesis was also severely impaired. However, the overall thymic architecture remained intact with distinctive cortical and medullary areas [26]. Dramatically reduced thymocyte numbers in γc-deficient mice were likely due to a γc requirement at the CD4, CD8-double negative (DN) stage where DN thymocytes undergo a >100-fold proliferative burst while differentiating into CD4+CD8+-double positive (DP) thymocytes [8, 30]. Indeed, the γc requirement turned out to be primarily a survival requirement, because γc-deficient DN thymocytes expressed dramatically lower levels of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 and were prone to apoptosis [8, 31]. Enforced Bcl-2 expression, on the other hand, partially rescued thymopoiesis and significantly increased overall thymocyte numbers in γc-deficient mice [22, 31, 32]. Nonetheless, transgenic Bcl-2 expression failed to restore thymocyte numbers to wild type levels, and it also did not relieve the developmental block of γc-deficient thymocytes at DN2/3 stage [8, 22]. Thus, γc is necessary for thymopoiesis to provide pro-survival signals but is also required in other aspects of T cell development, including proliferation and differentiation [8, 33, 34].

Importantly, whether γc was exclusively required at the DN stage could be not formally established solely based on the findings from germline γc-deficient mice. Germline γc−/− mice lack γc not only in DN thymocytes but in all thymocyte subsets. Therefore, it was not clear if thymic cellularity is dependent on γc expression only at the DN stage or also at later stages. This conundrum has been recently resolved in a study by Singer and colleagues, who generated a new conditional γc-deficient mouse (γc-cKO) where γc was deleted either at the late DN stage or in pre-selection DP thymocytes [35]. In γc-cKO mice, exons 2–6 of the γc gene were flanked with loxP sites, and the genomic region in-between was deleted using either the Cd4-Cre transgene at the late DN stage or the E8III-Cre transgene [36] at early DP stage. Notably, γc deletion after the late DN stage did not affect thymopoiesis so that overall thymocyte numbers were comparable to those of control mice [35]. These results formally demonstrated that thymic cellularity is established by γc expression at the early DN stage, precisely when DN thymocytes undergo IL-7-dependent proliferation and require survival signals [8, 37, 38].

While γc-deficiency after the late DN stage did not impact thymocyte numbers, strikingly, it showed a profound effect in thymocyte lineage commitment [35]. Positively selected thymocytes make cell fate decisions either into CD4 or CD8 lineage T cells, and the underlying molecular mechanism is subject of intense investigations [39]. Interestingly, differentiation of MHC-II-selected thymocytes into CD4 lineage cells remained intact in γc-cKO mice and did not require γc expression. However, CD8 lineage commitment of MHC-I-specific thymocytes was critically dependent on γc expression, so that CD8SP thymocyte numbers were dramatically reduced (~75 %) in γc-cKO mice. These results are in agreement with previous studies that indicated a non-redundant requirement for cytokine signaling to impose CD8 lineage fate on developing thymocytes [40–42]. Thus, T cell development in γc-cKO mice also formally demonstrates an in vivo γc requirement for CD8 lineage differentiation in the thymus [39]. Collectively, γc expression is required for both normal thymopoiesis and CD4/CD8 lineage choice, which are both necessary to establish a functional T cell compartment.

Even as γc is essential for T cells, the molecular basis for its requirement in thymopoiesis and T cell homeostasis was not immediately evident. When γc’s association with X-SCID was initially discovered, γc was only known as a component of the IL-2 receptor complex and presumed to be only involved in IL-2 signaling. However, IL-2-deficiency did not affect T cell development or impaired peripheral T cell survival [6]. Thus, γc was apparently required for signaling by cytokines other than IL-2 [3]. The responsible γc cytokine for thymopoiesis was later identified as IL-7 [43], which turned out to be also the major intrathymic cytokine to promote CD8 lineage differentiation [40, 42]. Importantly, it was further revealed that γc was a shared receptor subunit not only for IL-7 but also for a series of other cytokines, i.e. IL-4, IL-9, IL-15 and IL-21 [44–50]. However, even as γc is a shared component of multiple cytokine receptors, γc is essential for thymopoiesis because of its non-redundant requirement in IL-7 receptor signaling.

Protein tyrosine kinase JAK3 is required for γc signaling

γc was originally identified as a subunit of both the intermediate- and the high-affinity IL-2 receptor complex. The intermediate-affinity receptor is composed of the IL-2Rβ and γc, while the high-affinity receptor is composed of IL-2Rα, IL-2Rβ and γc, respectively [1, 51]. IL-2 binding assays revealed that γc was not necessary for IL-2 binding but essential for IL-2 signaling [52]. In fact, IL-2 binds with low affinity to the IL-2Rα chain (K d = 10−9 M) or with high affinity to IL-2Rα/β-chain complexes (K d = 10−11 M). However, these single chain receptors are unable to transduce IL-2 signaling in the absence of γc [49, 53]. Thus, γc recruitment and heterodimerization is a critical event, not for binding, but for signaling by IL-2.

None of the IL-2 receptor subunits, including γc, have intrinsic kinase activities or signaling capabilities. Therefore, they are dependent on receptor-associated protein tyrosine kinases to initiate downstream signaling. The kinase that is associated with γc is the Janus kinase-3 (JAK3) [47, 54, 55]. JAK3 is a 120 kDa cytosolic protein, initially isolated from NK cells and expressed in a tissue-restricted manner. JAK3 expression was primarily found in leukocytes, so that it was originally referred to as leukocyte-Janus kinase (L-JAK) [56]. JAK3 was the last member of the JAK kinase family to be identified [56–58], and its expression is mostly limited to lymphoid and myeloid cells [56–58]. In contrast, other JAK family members, such as JAK1, JAK2, and TYK2, are ubiquitously expressed, and accordingly, gene deficiencies in Jak1 [59] or Jak2 [60, 61] are lethal. TYK2-deficient mice, on the other hand, are born at Mendelian ratio and do not display any developmental abnormalities [62, 63], suggesting a redundancy of TYK2 with other JAK family members.

Ablation of JAK3 expression has been reported in both human and mice. In accordance with its preferential expression in lymphoid tissues, JAK3 deficiency did not affect overall development and did not result in premature lethality. Instead, JAK3 deficiency had a profound effect on lymphocyte development as initially reported for humans [64, 65] and subsequently demonstrated in three independent animal studies [66–68]. JAK3 deficiency in humans was associated with autosomal recessive SCID that manifested in T−B+NK− deficiency [64, 65], and that was highly reminiscent of the γc-mediated X-SCID phenotype. In fact, the clinical manifestations of γc and JAK3 deficiencies are virtually identical. Notably, this was also the case in mice as JAK3 deficiency phenocopied the immunodeficiency observed in γc−/− mice.

JAK3-deficient mice were generated by Berg and colleagues who replaced a part of the JAK3 kinase domain with a neomycin cassette [66], and also by Ihle and colleagues who disrupted the Jak3 gene by inserting a hygromycin cassette after the ATG start codon [67]. Additionally, Saito and colleagues generated Jak3 −/− mice by replacing the pseudo-kinase and part of the kinase domain with a neomycin cassette [68]. The results of these gene targeting studies were unambiguous. Lymphocyte development in JAK3-deficient mice was severely impaired with profound reduction in mature B- and T cell numbers and complete loss of NK cells. Additionally, dendritic epidermal T cells and intestinal γδ T cells were absent. The few surviving αβ T cells displayed intact TCR signaling but defective signaling by IL-2 and other γc cytokines. Collectively, these results document that JAK3 is essential in lymphocyte development and function, and they reveal that JAK3 is required because of its non-redundant role in γc cytokine signaling.

Because JAK3 is constitutively associated with γc, it was interesting to know whether JAK3 is only required for its kinase activity or if it also has other regulatory functions. Indeed, a chaperone-like function to facilitate the transport and surface expression of associated receptors had been described for JAK family molecules. For example, JAK2 associates with the erythropoietin receptor (EpoR) and promotes EpoR folding in the endoplasmic reticulum and facilitates its transport to the plasma membrane. Thus, effective cell surface expression of EpoR is JAK2-dependent [69]. Additionally, other JAK family members such as TYK2 and JAK1 exert similar functions for the IFN-α receptor 1 (IFNAR1) and oncostatin M receptor (OSMR), respectively. TYK2 stabilizes and increases cell surface IFNAR1 expression [70], while JAK1 masks a negative regulatory motif in the intracellular domain of OSMR to retain and promote its cell surface expression [71]. These studies unveiled a previously unappreciated role for JAK family molecules in controlling surface expression of their associated cytokine receptors, independent of their kinase functions. Such a mechanism might be of importance in modulating cytokine response, because it can limit the availability of surface cytokine receptor expression.

Curiously, JAK3 seemed to lack such regulatory function, because γc surface expression did not require JAK3 [72]. More surprisingly, surface γc expression was actually increased on JAK3-deficient cells [72, 73]. These results suggested a negative regulatory role for JAK3 in γc expression, which could involve either a direct effect of JAK3 on γc protein expression or an indirect effect due to aberrant immune activation in Jak3 −/− mice [74]. In fact, T cells from JAK3-deficient mice show signs of constitutive activation [66]. Because γc expression is upregulated upon T cell activation [53, 75, 76], increased γc levels on Jak3 −/− cells could be attributed to a phenotype associated with T cell activation. Results from EBV-transformed cell lines of JAK3-deficient patients, however, argue against this possibility because these cells were quiescent but still expressed high levels of surface γc [73]. Moreover, total γc protein expression was not increased in Jak3 −/− cells, despite having increased γc surface expression [73]. These results suggest that JAK3 does not affect the amount of γc proteins but presumably influences the transport or intracellular distribution of pre-existing γc proteins. Alternatively, γc expression could be elevated due to inefficient γc receptor internalization as a consequence of impaired cytokine signaling in the absence of JAK3. Further exacerbating this confusion is the finding that JAK3 overexpression resulted in significantly increased surface γc expression in JAK3 transfectants [73]. Thus, γc surface expression is upregulated by both increases and decreases in JAK3 expression. The molecular basis of JAK3-dependent γc expression is not known and awaits further investigations.

Distinct γc cytokine signaling threshold in T cells

Little is known about the cellular mechanisms that control γc expression. While JAK3 evidently affects γc surface expression, γc ubiquitination and cytokine-induced internalization are also proposed to regulate γc expression [77]. Additionally, a post-transcriptional mechanism that regulates membrane γc expression has also been reported [18]. But whether and to what extent these processes contribute to tissue- and lineage-specific γc expression is unclear. In this regard, the transcriptional mechanisms of γc expression are even less explored. Nonetheless, the γc promoter has been mapped, and the −90/34 bp region of the γc transcriptional start site was found to contain a couple of conserved Ets transcription factor binding sites to which GA-binding proteins and the transcription factor Elf-1 were bound [78]. Luciferase assays further showed that this promoter region was sufficient to impose tissue specificity, because the γc promoter construct was active in hematopoietic cells but not in non-hematopoietic tissues or cell lines, including primary fibroblasts, hepatoma cells and colon cancer cell lines [78]. Moreover, transfection of Ets-family proteins GABPα and GABPβ strongly induced basal promoter activity of γc luciferase constructs in HeLa cells, indicating that GA-binding proteins can act as transactivators of γc transcription. Whether GABP controls γc expression in vivo remains unknown. However, conditional GABPα knock-out mice have been reported [79], and they thus provide an opportunity to address these questions.

Unfortunately, little progress has been made beyond this point in terms of understanding γc regulation. There is possibly also a lack of interest because of the misconception that γc expression is constitutive and not transcriptionally regulated. Indeed, the γc promoter was found to lack both TATA and CAAT boxes, displaying classical features of a housekeeping gene [78]. In agreement, all lymphoid cells do express γc in a constitutive manner. On the other hand, γc level differs between lymphocyte subsets and can change depending on their activation status. For example, during T cell development in the thymus, γc is highly expressed on immature DN and post-selection thymocytes but significantly downregulated on pre-selection DP thymocytes [35, 75]. T cell activation also induces γc expression as demonstrated by TCR stimulation in vitro [18, 53, 75] or upon viral infection in vivo [80]. Thus, γc expression is not developmentally set but actively regulated during T cell development and activation.

Regulating γc expression is important because a growing body of evidence indicates that the amount of γc proteins determines the signaling threshold for γc cytokine signals. For example, γc downregulation by short interfering RNA induced diminished JAK3 activity and impaired the proliferation of B lymphoblastoid cell lines [81]. Furthermore, partial reconstitution of γc-deficient T cells with retrogenic γc constructs demonstrated a graded cytokine response depending on the level of transduced γc expression. In brief, depending on the retrogenic γc construct, transduction of γc-deficient bone marrow resulted in different levels of γc expression, and accordingly, the number of developing T cells and their IL-2 response were different [82]. Increased γc expression directly correlated with increased T cell numbers and increased IL-2-induced phosphorylation of STAT5.

Interestingly, individual γc cytokines seem to have distinct sensitivities to γc expression levels. IL-7 required larger amounts of surface γc than IL-2 or IL-15 for downstream STAT5 activation [83]. Such difference was illustrated in an atypical SCID patient, who had a single nucleotide splice-site mutation in intron 3 of the γc gene. Aberrant splicing resulted in profound reduction of correctly spliced γc mRNA and dramatically diminished γc expression, down to levels that were not detectable by surface staining [84]. Consequently, this patient was deficient in T cells which are critically dependent on IL-7 for their generation. Surprisingly, however, the trace amount of γc was sufficient to permit IL-15-dependent NK cell generation, resulting in an unusual T−NK+ X-SCID phenotype [84]. The requirement for distinct levels of γc was further demonstrated in EBV-transformed B cells from this patient. While low level γc expression was sufficient to permit IL-2- and IL-15-mediated signaling, it did not suffice for IL-7-dependent STAT5 phosphorylation. Finally, using an array of promoter constructs with different activities, a series of γc transfected cells with decreasing amounts of surface γc expression were established and tested for IL-2, IL-15 and IL-7 signaling. The results were unequivocal, and they demonstrated a strict linear relationship of transfected γc levels and cytokine induced STAT5 phosphorylation. In agreement with different signaling thresholds for individual γc cytokines, down-titration of γc expression first resulted in the loss of IL-7 signaling followed by loss of IL-2 and IL-15 responsiveness [83].

The molecular basis for such differences is not fully understood. Possibly, IL-7 receptor signaling might require a larger number of minimal signaling units to initiate downstream signaling, compared to signaling by the IL-2 or IL-15 receptor complexes. Also, potential contributions of the proprietary α-chains, i.e. IL-2Rα and IL-15Rα, which increase affinity and stabilize the signaling complex need to be considered. Collectively, limiting the amount of γc expression impairs γc cytokine signaling, and individual cytokines require different levels of γc.

Downstream signaling of γc in T cells

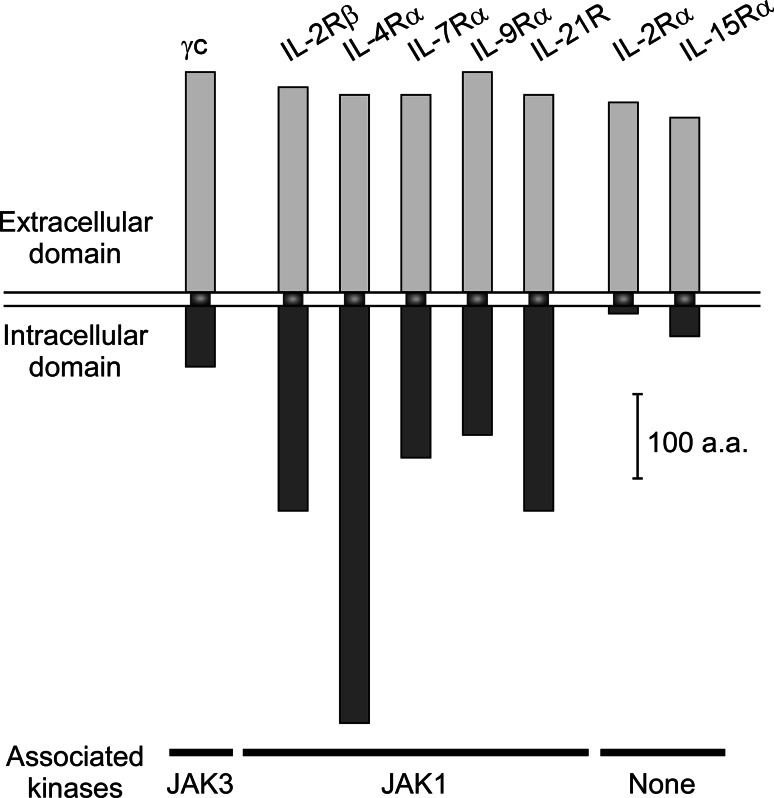

Signaling of γc cytokines is triggered by hetero-dimerization of a proprietary cytokine receptor with the shared γc chain. Hetero-dimerization brings the intracellular domains of the receptors into close physical proximity, and thus leads to trans-phosphorylation and activation of receptor-associated protein tyrosine kinases. All proprietary receptors of the γc cytokine family, i.e., IL-2Rβ, IL-4Rα, IL-7Rα, IL-9Rα, and IL-21R, are associated with the protein tyrosine kinase JAK1 (Fig. 1) [1]. The γc receptor, on the other hand, is constitutively associated with JAK3 [47]. IL-2Rα and IL-15Rα are the exceptions as they are not associated with any kinases and only serve to increase the affinity of the receptor complex for cytokine binding. γc association with JAK3 is highly selective, and γc exclusively binds to JAK3 [47, 85]. Activated JAK1/JAK3 molecules phosphorylate specific tyrosine residues in the cytosolic tails of cytokine receptors, which in turn attract further downstream signaling molecules and results in their activation by JAK. In sum, all γc cytokines share the common feature to initiate signaling by trans-phosphorylation of JAK1/JAK3. Activation of JAK1/JAK3 triggers a common signaling pathway mediated by STAT5 and phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) so that all γc cytokines, without exception, signals through activation of STAT5 and PI3K. Consequently, γc cytokines display many common signaling effects, such as upregulation of anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 and promotion of pro-metabolic activities [1].

Fig. 1.

Size and structure of the γc cytokine receptor family. Schematic depiction of γc family cytokine receptors. The common γc is constitutively associated with the kinase JAK3. The proprietary cytokine receptors IL-2Rβ, IL-4Rα, IL-7Rα, IL-9Rα, and IL-21R are associated with JAK1. IL-2Rα and IL-15Rα have short intracellular domains without kinase binding activities. Upon ligand engagement, γc forms a signaling-competent heterodimer with a proprietary cytokine receptor, allowing for transactivation of the receptor-bound JAK proteins

Curiously, even as they share common signaling pathways, each γc cytokine also plays a unique and non-redundant role in T cell biology. For example, IL-7 signaling is essential for thymopoiesis, IL-15 is uniquely required for NKT cell development, and IL-2 is critical for Foxp3+ Treg cell differentiation [11]. Thus, it is puzzling how the same JAK1/3-STAT5 signaling cascade can induce all these distinct biological effects. Having diverse functions while sharing a common receptor subunit is characteristic of γc family cytokines. It contrasts with cytokines of the common β-chain (βc) or the gp130 receptor families, which share a common βc or a common gp130 cytokine receptor, but display rather overlapping and redundant biological effects [86]. An explanation for such disparity may lie in the difference of which receptor component is utilized to recruit downstream signaling molecules. For βc and gp130 family cytokines, the shared βc or the gp130 receptor is the central signaling scaffold, having the longest intracellular domain and also serving as site of STAT recruitment and phosphorylation [86]. The γc, on the other hand, has the shortest intracellular domain among all signaling-competent γc cytokine receptors (Fig. 1), and there is no evidence that STAT or PI3K is recruited to its tail. In fact, it is the proprietary cytokine receptors that contain the specific tyrosine residues to recruit downstream STAT and other signaling molecules. Thus, signaling of γc family cytokines is transduced through individual proprietary receptors, whereas signaling of βc or gp130 cytokines is transduced through the shared receptors. These findings can explain why different γc cytokines display distinct effects even as they share a common receptor for signaling. In further support of this idea, tail-swapping experiments demonstrated that the intracellular domains of the proprietary receptors determine the substrate specificity and downstream signaling effects [87].

These results suggest a streamlined model of γc receptor signaling, where γc’s role is limited to the recruitment of JAK3 to transactivate JAK1. Consequently, JAK1 is the major player in γc cytokine signaling, and JAK3 would be only required to activate JAK1. A dominant role of JAK1 over JAK3 was further illustrated in a recent report that showed signaling of γc-dependent cytokines such as IL-7 being constrained by the cellular abundance of JAK1 proteins [88]. According to this study, JAK1, but not JAK3, is a highly unstable protein, and continuous synthesis of new JAK1 protein is required to maintain effective IL-7 signaling. As a corollary, inhibition of JAK1 protein synthesis by microRNA interference resulted in significantly reduced IL-7 signaling, which was precisely the case in TCR-signaled T cells. TCR activation induced expression of microRNA-17 (miR-17), and miR-17 bound to a conserved site in the 3′ UTR of JAK1 to inhibit JAK1 translation and reduce abundance of JAK1 protein [88]. Lower expression of JAK1 proteins, on the other hand, directly correlated with diminished IL-7 signaling. It has been appreciated for a long time that TCR engagement interferes with γc signaling and desensitizes IL-7Rα and other γc family cytokine receptors [36, 89–91]. Multiple mechanisms had been put forward to explain the molecular basis for cytokine receptor desensitization, including proteolysis of the γc cytosolic tail by calcium-induced proteases or activation of the MAPK and calcineurin pathways [90, 92]. The study by Singer and colleagues is important because it reveals a new level of regulation in TCR-induced cytokine receptor desensitization that involves translational inhibition of JAK1 by miRNA and which further unveils JAK1 protein as a limiting factor in γc cytokine signaling. Altogether, these findings identify JAK1 protein expression as a linchpin in orchestrating cytokine signaling through γc.

A preeminent role for JAK1 was further documented in transfection studies, which showed intact IL-2 signaling in wild type JAK1 + kinase-dead JAK3 expressing cells, but impaired IL-2 signaling in kinase-dead JAK1 + wild type JAK3 transfected cells [93]. Thus, it is the kinase activity of JAK1, and not JAK3, that induces phosphorylation of the cytokine proprietary IL-2Rβ chain to trigger downstream signaling. Of note, because kinase-dead JAK3 was sufficient to activate JAK1 [93], these results also opened up the possibility that JAK1 phosphorylation might not be a prerequisite for JAK1 activation. Instead, aggregation of JAK molecules that induces conformational changes of JAK1 into an active form could be sufficient to initiate γc signaling. Whether this is actually the case in primary T cells still needs to be examined. Nonetheless, these in vitro data favor a model where the principal function of γc is to recruit JAK3 to close proximity of JAK1, and thus leads to JAK1 activation and JAK1-mediated phosphorylation of the cytokine receptor for recruitment of downstream signaling molecules.

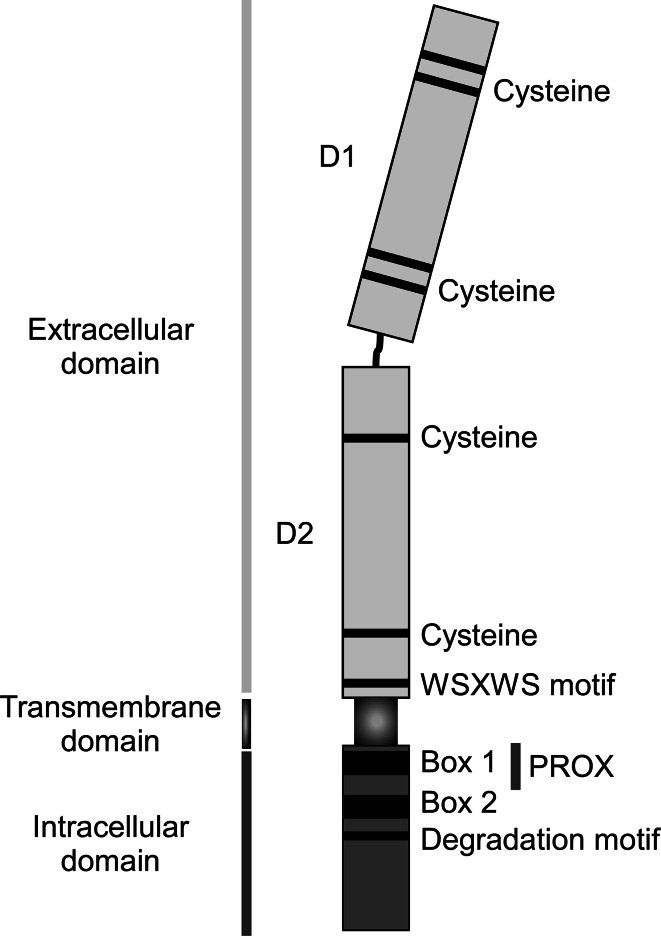

In contrast to this view, there is also a large body of evidence suggesting that γc plays additional roles beyond recruitment of JAK3 [94]. In a classic study, Greenberg and colleagues generated a series of chimeric γc receptor molecules, including a construct where the entire γc intracellular domain was excised and replaced with JAK3 [95]. Surprisingly, this chimeric γc receptor was unable to activate downstream signaling, illustrating that JAK3 recruitment alone is not sufficient for γc signaling. In fact, the same study demonstrated that a short stretch of the membrane proximal region (cytoplasmic residue 5–37), also known as PROX, is necessary for JAK activation (Fig. 2). PROX is conserved among other cytokine receptors, such as IL-3Rα and IL-5Rα, and shows partial homology with SH2 domains [96]. The PROX region also contains a conserved binding motif, known as Box 1, which corresponds to a stretch of six to ten proline-rich amino acids that mediate interaction of cytokine receptors with JAK molecules [94]. Notably, a chimeric γc construct, where the γc intracellular domain was replaced with a PROX + JAK3 construct, successfully transduced γc signaling, which however was not the case when replaced with JAK3 alone [95]. Therefore, the PROX region is a critical element of γc that is required for γc cytokine signaling. Why JAK activation requires the PROX region remains unclear. One possibility is that signaling intermediary molecules could bind to PROX and that they would be required for JAK activation. Alternatively, PROX could promote JAK3 activity by placing it in the correct orientation or conformation for transphosphorylation with JAK1. Recent reports indicated that the correct orientation of receptor-associated JAK molecules is indeed a new variable that needs to be considered. In brief, homodimerization of proprietary cytokine receptors is usually insufficient to trigger signaling and proliferation [97, 98]. However, certain IL-7Rα mutations in humans that forced IL-7Rα homodimerization, induced constitutive activation of the IL-7R signaling pathway, leading to uncontrolled proliferation and leukemogenesis [99]. A recent study reconciled this discrepancy by pointing out a role for spatial organization of the receptor-associated cytosolic kinases, which presumably requires the kinases to correctly face each other for transactivation [100]. Accordingly, physical proximity of cytokine receptors is normally insufficient to trigger signaling. However, receptor mutations that twist the intracellular tails to re-orient JAK and juxtapose it to the opposite JAK molecule can induce signaling of homodimeric receptor, even in the absence of ligands [100]. Therefore, a role for PROX in placing JAK3 into the correct orientation is an attractive idea that warrants further investigations.

Fig. 2.

Structure of the γc cytokine receptor. The extracellular structure of γc is characterized by two type III fibronectin domains that form a disulfide-bond-mediated tertiary structure necessary for interactions with other members of the γc receptor family. A member of the type I cytokine receptor family, γc possesses the characteristic membrane proximal WSXWS motif found in all members of the family. The intracellular domain of γc possesses four defined tyrosine residues of unknown importance. JAK3 binding to the intracellular domain of γc is mediated by Box 1 and Box 2 motifs, which are located close to the plasma membrane and adjacent to the internalization/degradation domain necessary for proper membrane localization, ligand-mediated internalization and lysosomal degradation

The intracellular domain of γc is characterized by the presence of 2 conserved JAK3 binding domains, referred to as Box 1 and Box 2. Box 1 is at the N-terminal end of the PROX region, and Box 2 is a stretch of 14 amino acids immediately downstream of PROX [96]. γc deletion mutants lacking all but six amino acids of the cytoplasmic domain (ΔCT) and γc mutants lacking the C-terminal 48-amino acids of γc (ΔSH2) demonstrated that Box 1 and Box 2 are absolutely necessary for JAK3 association and cytokine-induced STAT5 activation in both cell lines and in mice [45, 101]. Interestingly, the membrane proximal region of γc, encompassing 52 amino acids and including Box 1 and Box 2, is sufficient for JAK3 binding, JAK1/JAK3 activation, and triggering downstream signaling events [96], indicating that the PROX region is possibly both necessary and sufficient for γc signaling. Whether other parts of the γc intracellular domain contribute to γc signaling is not fully resolved. Four tyrosine residues are present in the intracellular region, but none of them are embedded in the classical SH2 binding motif of Y-X-X-M or Y-X-X-L, which makes it unlikely that any of them serve as a docking site for downstream signaling molecules. In agreement, phenylalanine substitution of any or all four of these tyrosine residues did not impede γc-induced proliferation in transfected T cells [96, 102]. Nonetheless, IL-2 signaling does induce tyrosine phosphorylation of γc protein [103], and other mutagenic studies have found γc phosphorylation being critical for anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 upregulation [104]. Thus, the exact role of the γc cytoplasmic tail remains controversial and requires further interrogations.

Alternative splicing generates soluble γc chains

The murine γc chain is 64 kD type I transmembrane receptor consisting of a 270 amino acid extracellular domain, a 29 amino acid transmembrane domain, and 85 amino acid intracellular tail [105]. Among all γc family cytokine receptors, γc has the largest extracellular domain but curiously the shortest cytoplasmic tail (Fig. 1). Nonetheless, the cytoplasmic tail is essential for γc function, so that truncation mutants lacking the intracellular domain are non-functional [101, 102]. Tailless γc proteins are still exported to the plasma membrane, indicating that the cytosolic tail is not required for γc surface expression. In fact, tailless γc proteins are expressed at even greater amounts on the cell surface, presumably because internalization and degradation of surface γc proteins are impaired [101]. Potentially, such tailless γc receptors could interfere with γc signaling because the extracellular domain remains intact and could heterodimerize with proprietary cytokine receptors. If so, heterodimers of truncated γc and proprietary cytokine receptors would bind cytokines but not generate productive downstream signal. Tailless γc transgenic mice have been reported [101], but whether truncated γc proteins indeed compete with endogenous surface γc proteins and dampen γc signaling has not been tested.

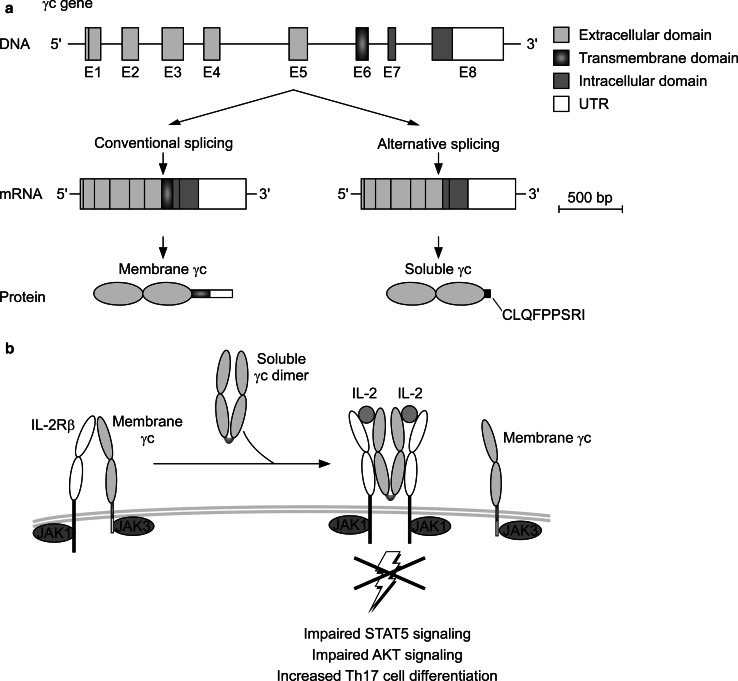

Tailless γc proteins with transmembrane domains are expressed as membrane-bound molecules on cell surface [101]. Recently, a new and naturally occurring form of tailless γc had been reported which not only lacks the intracellular domain but also the transmembrane domain [18]. This truncated form of γc was not expressed on the cell surface but secreted as a soluble γc protein. Indeed, soluble γc (sγc) proteins were found in serum of both humans and mice, and they were found to be expressed at higher levels upon T cell activation and inflammation [18, 106]. Notably, sγc was not a product of shedding or proteolytic cleavage of pre-existing membrane γc proteins, which are mechanisms that are classically associated with soluble cytokine receptor generation in T cells [107]. Instead, sγc was generated by alternative splicing of the γc pre-mRNA (Fig. 3a).

Fig. 3.

Alternative pre-mRNA splicing generates soluble γc proteins. a The γc gene is located on the X chromosome and possesses eight exons (E1–E8). Exons 1–5 correspond to the extracellular domain, while exon 6 codes for the transmembrane domain. Exons 7–8 form the intracellular domain. Conventional pre-mRNA splicing produces a mature transcript which encodes the signaling-competent transmembrane form of γc. However, alternative splicing induces the formation of a soluble γc splice form which lacks the transmembrane domain. b The alternative transcript encodes a secreted γc protein (sγc) that homodimerizes and can directly bind to IL-2Rβ, even in the absence of IL-2. sγc association with IL-2Rβ inhibits its interactions with membrane-bound γc (membrane γc), thus limiting the ability of the receptor complex to signal. sγc inhibits STAT5 and AKT signaling but promotes Th17 cell differentiation, so that sγc is a naturally occurring pro-inflammatory mechanism

The γc gene is composed of eight exons, among which exons 1–5 encode the extracellular domain and exons 7–8 encode the intracellular region. The entire transmembrane domain is encoded in a single exon, exon 6. The full-length form of γc which is expressed on the cell membrane (mγc) contains all eight exons. However, alternative splicing resulted in omitting exon 6 and generating an alternate γc product that lacks the transmembrane domain. Moreover, skipping exon 6 and splicing exon 5 directly to exon 7 induced a frameshift in the γc open reading frame that introduced a new C-terminal epitope of nine amino acids, CLQFPPSRI, followed by a stop codon. Thus, alternative splicing creates a new protein that comprises the entire ectodomain of γc but lacks both the transmembrane and intracellular domains. Notably, this pre-mRNA splice isoform was translated and secreted as a soluble protein and could be detected in serum and culture supernatants of activated T cells. Evidence that soluble γc is a product of alternative splicing, and not of shedding, was provided by the fact that anti-γc serum immunoprecipitates strongly reacted with CLQFPPSRI-specific antibodies [18]. This nonameric epitope is absent from membrane γc proteins and only found in sγc proteins. Thus, anti-CLQFPPSRI reactivity demonstrated that sγc in serum and culture supernatant is a product of alternative splicing. Moreover, in mice that are unable to produce alternatively spliced γc mRNA, serum was completely devoid of soluble γc proteins, indicating that all sγc proteins are generated by alternative splicing. sγc-deficient mice were generated by breeding transgenic mice that express a pre-spliced full-length γc cDNA (γcTg) with mice that are deficient in γc (γc−/−). The resulting γcTgγc−/− mice only expressed membrane γc (mγcTg). Thus, mγcTg mice represent a new experimental model of sγc-deficiency that can be used to interrogate the role of sγc in vivo and potentially in translational studies. Along these lines, alternative splicing of γc was also found in humans, where the open reading frameshift resulted in generation of a seven amino acid epitope, RCPEFPP, followed by a stop codon [18]. Thus, the alternative splice isoform of γc is an evolutionary conserved mechanism to generate soluble γc.

Other members of the γc cytokine receptor family also produce soluble forms, and they have been identified in both humans and mice. These include IL-2Rα [108, 109], IL-2Rβ [110], IL-4Rα [111], IL-7Rα [112], IL-9Rα [113], and IL-15Rα [114]. A common feature shared amongst these soluble γc family receptors is that they retain their affinity for their cognate cytokine ligands. Consequently, these secreted proteins could either compete with membrane cytokine receptors for ligand binding—thereby sequestering the cognate cytokine and limiting its bioavailability—or, as is the case for soluble IL-15Rα, serve as a platform for cytokine trans-presentation [115]. Such a mechanism dramatically increases the effective concentration of a given cytokine, and can act in an agonistic fashion to increase its biological effect. However, unlike all other γc family cytokine receptors, the extracellular domain of γc has no intrinsic affinity for any cytokine. This feature sets the γc apart from other cytokine receptors, and made it also difficult to predict a biological function for a soluble γc protein.

Pre-association of γc with surface cytokine receptors

The extracellular region of γc interacts with both the cytokine and the proprietary cytokine receptor [116–119]. The γc ectodomain forms two fibronectin type III (FN-III) domains—known as D1 and D2—a motif that is found in many growth hormone and interleukin receptors (Fig. 2). The D1 domain (a.a. 32–125) contains conserved cysteine residues that form intramolecular disulfide bonds, and the D2 domain (a.a. 129–226) contains a membrane proximal WSXWS motif which is critical for conformational changes of the receptor [117, 118]. Structural studies from the high-affinity IL-2 receptor revealed that γc interacts with both the cytokine and the cytokine-specific receptor at the same time. γc interacts with IL-2Rβ through the D2 domain, while γc interaction with IL-2 is mediated by both the D1 and D2 domains [117, 118]. Importantly, the γc/IL-2 interface is the smallest of all protein interaction interfaces in the IL-2/IL-2R complex, and it is characterized by weak electrostatic interactions leading to low specificity and low binding affinity to IL-2. In fact, γc itself possesses no intrinsic cytokine binding capacity, and the γc ectodomain does not bind free cytokines [120].

However, γc dramatically increases the cytokine binding affinity of proprietary cytokine receptors, such as IL-4Rα, IL-7Rα and IL-2Rβ (Table 1). The contribution of γc varies among different proprietary cytokine receptors, and it has the strongest effect on IL-2Rβ which results in ~100-fold increase of IL-2 binding. Because γc alone does not bind cytokines, these observations put forward a model where IL-2 first binds to the IL-2Rβ with intermediate affinity, and IL-2 binding induces conformational changes in the IL-2Rβ to expose new epitopes composed of a combination of IL-2/IL-2Rβ. The cytokine-bound receptor complex then attracts γc and brings the intracellular domains of γc and IL-2Rβ to close proximity for transactivation of JAK1 and JAK3. Accordingly, cytokine-induced receptor activation follows a sequence of conformational changes that goes through “initiation”, “intermediate” and “activation” configurations [19]. This stepwise binding model is also known as the “affinity conversion” model [121], and it posits that γc only associates with cytokines that are pre-bound with their proprietary cytokine receptor chains. Moreover, this model also posits that heterodimerization of the “shared” γc with other “private” cytokine receptors is a ligand-induced event, and that γc remains unbound with other receptors in the absence of cytokines. In support of this model, surface plasmon resonance (SPR) studies with recombinant γc ectodomain proteins reported absence of detectable γc binding affinity to IL-2Rβ [120, 122]. Thus, heterodimerization of γc and cytokine proprietary receptors seemed to be strictly dependent on cytokines.

Table 1.

Affinity of γc cytokine receptor family members for their ligands in the absence or presence of γc

| Receptor | Ligand | Affinity (K d) without γc (M) | Affinity (K d) with γc (M) | Affinity increase with γc (fold) | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IL-2Rβ | IL-2 | 1.0 × 10−7 | 1.0 × 10−9 | ~100 | [52] |

| IL-2Rβ | IL-15 | 1.9 × 10−10 | 2.7 × 10−11 | ~7 | [48] |

| IL-4Rα | IL-4 | 2.7 × 10−10 | 7.9 × 10−11 | ~3 | [45] |

| IL-7Rα | IL-7 | 2.5 × 10−10 | 4.0 × 10−11 | ~6 | [50] |

| IL-9Rα | IL-9 | 2.3 × 10−10 | 2.2 × 10−10 | ~1 | [46] |

Affinity increase with γc (fold) = “K d with γc/K d without γc”

However, SPR studies are conducted with receptor proteins that are in solution, so that they might not reflect the actual events on cell surface. In fact, analysis of γc and cytokine receptor interactions in cell membranes painted a quite different picture. Contrary to the prediction of the affinity conversion model, fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) analysis of resting T cells revealed the presence of pre-assembled IL-2Rβ/γc heterodimers, even in the absence of cytokines [123]. Moreover, FRET analysis of full length or truncated IL-2Rβ and γc chains demonstrated that these receptors spontaneously assemble on the cell surface through interactions of their extracellular domains [21]. Formation of ligand-independent IL-2Rβ/γc complexes was further demonstrated by immunofluorescence co-patching studies in cytokine receptor transfected cells [124], and by co-immunopreciptiation of γc with IL-2Rβ in the absence of IL-2 [125]. Thus, membrane γc can pre-associate with IL-2Rβ before IL-2 stimulation. Importantly, pre-association of IL-2Rβ/γc heterodimers did not result in ligand-independent γc receptor signaling. Structural analysis predicted that IL-2Rβ/γc heterodimers are assembled in such a way that it pushes apart the transmembrane and intracellular domains from each other, preventing JAK transactivation in the absence of cytokines. IL-2 stimulation, however, pulls the transmembrane domains much closer together and initiates signaling. These results suggested that the role of cytokines is to induce conformational changes in the preformed receptor complexes, leading to juxtaposition and transactivation of intracellular JAK molecules. According to this “pre-association” model, IL-2-free IL2Rβ/γc chains are pre-associated on the cell membrane and assume a configuration that pushes the transmembrane domains apart (65 Å). IL-2 binding then changes the configuration of the dimers, rotating the γc receptor 90° and bringing the transmembrane domains of γc and IL-2Rβ to close enough proximity (32 Å) for JAK transactivation [21]. Notably, ligand-independent γc pre-association has not been only reported for IL-2Rβ, but also for IL-7Rα and IL-9Rα [18, 20, 124–126], suggesting that ligand-independent γc pre-association might be a general feature of the γc receptor.

Soluble γc chain is a naturally occurring pro-inflammatory mechanism

A major implication of the “pre-association” model is the direct binding of γc to proprietary cytokine receptors (Fig. 3b). As a corollary, sγc proteins could possibly also bind to cell surface cytokine receptors. However, recombinantly expressed γc ectodomain proteins displayed very low affinity to IL-2Rβ proteins, so that a direct interaction of sγc with IL-2Rβ in solution was considered unlikely [120, 122].

On the other hand, alternatively spliced sγc differs from conventional recombinant γc ectodomain proteins because it can form inter-molecular disulfide bonds through the cysteine residue in the C-terminal CLQFPPSRI epitope (Fig. 3a). A cysteine residue is also created upon alternative splicing in the C-terminal RCPEFPP epitope of human sγc. Thus, sγc differs from membrane γc, not only that it is soluble, but also that it can be expressed as homodimeric proteins. Indeed, most of serum sγc proteins in vivo, and also recombinantly expressed recombinant sγc proteins in vitro, existed in a disulfide-linked dimeric form [18]. Remarkably, sγc dimerization significantly increased (~50-fold) sγc binding affinities for proprietary cytokine receptors, namely IL-7Rα and IL-2Rβ, and enabled direct sγc binding to surface cytokine receptors on T cells. sγc binding occurred even in the absence of cytokine stimulation, and interfered with γc cytokine signaling. Specifically, treatment of T cells with recombinant sγc potently inhibited IL-2-induced STAT5 phosphorylation, and sγc transgenic mice expressing increased levels of sγc showed impaired T cell development and homeostasis, consistent with an inhibitory effect of sγc on IL-7 signaling [18]. Thus, sγc is a new naturally occurring mechanism that inhibits γc cytokine signaling by directly binding to IL-2Rβ and IL-7Rα.

The biological significance of sγc was illustrated in the in vivo setting of T cell-mediated autoimmunity models. IL-17-producing CD4+ Th17 cells are pro-inflammatory T cells that mediate autoimmune diseases such as colitis and brain inflammation [127]. Th17 cell generation can be inhibited by IL-2, and conversely, inhibiting IL-2 signaling promotes Th17 cell differentiation [128]. Because recombinant sγc proteins suppress IL-2 signaling, sγc promotes Th17 cell differentiation in vitro and sγc transgenic mice had increased numbers of IL-17 producing cells in vivo [18]. In fact, increased amounts of sγc created a pro-inflammatory environment, so that sγc transgenic mice were prone to inflammatory autoimmune diseases. Specifically, when challenged in a murine model for multiple sclerosis, experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) [129], sγc transgenic mice showed an earlier onset of disease, more severe disease phenotype and delayed or absence of remission [18]. Thus, increased sγc expression exacerbates disease severity in an inflammatory autoimmune model. These results correlated with observations in humans, where synovial fluids of rheumatoid arthritis patients or sera of Crohn’s disease patients showed high levels of sγc proteins [130, 131]. Importantly, while sγc proteins had been previously described [130, 132], it was not known whether increased sγc expression is the cause or consequence of inflammatory autoimmune disease. Since sγc is expressed by activated T cells and sγc promotes inflammatory Th17 cell differentiation, these findings suggest that sγc is pro-inflammatory and contributes to the severity of inflammatory diseases.

In contrast to the effect of increased sγc expression, the absence of sγc ameliorated the severity of autoimmune diseases. This was the case for sγc-deficient mγcTg mice when they were induced for EAE, and also when naïve mγcTg CD4+ T cells were adoptively transferred into RAG-deficient hosts to induce inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Compared to wild type control mice, EAE disease severity was profoundly diminished in mγcTg mice. Also, colitis score and inflammatory Th17 cell numbers were dramatically reduced in IBD-induced host mice injected with mγcTg donor CD4+ T cells [18]. Altogether, these data indicate that sγc is a naturally occurring regulatory mechanism by activated T cells that determines the severity of autoimmune disease.

Upon infection by foreign pathogens, however, sγc might play a beneficial role by eliciting a rapid and potent pro-inflammatory response that ensures swift clearance of pathogens. T cell activation necessarily results in IL-2 production that drives clonal expansion of antigen-challenged T cells [133]. IL-2, however, potently suppresses IL-17-mediated pro-inflammatory responses as it impairs Th17 cell differentiation [128], which, on the other hand, is important for pathogen clearance and host defense [134]. Thus, sγc production by activated T cells might have been evolved to equip T cells with the ability to mount effective Th17 responses while residing in an IL-2 rich environment. Collectively, these observations establish sγc as a critical effector molecule for T cells and also as a new regulator of inflammatory diseases, suggesting that sγc might be a novel target for immunotherapeutic intervention.

Conclusions and perspectives

Identification of the γc cytokine receptor provided solutions to a number of questions that had long puzzled immunologists. It provided the genetic solution to X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency [3], explained the three distinct IL-2 binding affinities in IL-2Rα and IL-2Rβ transfected lymphoid cells [135], and provided the molecular basis for the compound effect of γc-deficiency on multiple γc cytokines [1]. Characterization of γc also raised further questions that triggered the discovery of new cytokine signaling mechanisms and provided new perspectives on cytokine receptor utilization and sharing. For example, IL-4 can still signal in the absence of γc which led to identification of an alternative IL-4 signaling pathway, independent of γc [136]. Indeed, IL-4 can signal through an alternate type II IL-4 receptor complex that is composed of the IL-4Rα/IL-13Rα1 chains instead of the classical IL-4Rα/γc and JAK1/JAK3 signaling machinery [137]. Furthermore, γc-deficiency results in severely impaired thymopoiesis, but IL-7Rα-deficiency had an even more profound effect on T cell development, suggesting that IL-7Rα might pair with a cytokine receptor other than γc to promote thymopoiesis. The identification of the TSLP receptor, which heterodimerizes with IL-7Rα to activate JAK/STAT, provided an explanation for this observation [138]. Like IL-7, TSLP is expressed by thymic stromal cells and is partially redundant with IL-7 in thymocyte development [139]. Sharing the IL-7Rα with IL-7, but not with γc, revealed an ever more complex cytokine receptor network.

The identification of soluble γc now adds another layer of γc regulation and reinforces the pleiotropic role of γc in T cell biology. sγc proteins are interesting because they represent a new negative regulatory pathway in γc signaling. On one hand, the protein product of γc alternative splicing directly binds to cytokine receptors and inhibits their signaling. On the other hand, generation of sγc splice isoforms conversely results in reduced splicing into mγc. Because increased sγc expression is necessarily associated with decreased mγc expression, sγc represents a post-transcriptional mechanism to downregulate surface γc expression. Indeed, immature DP thymocytes expressed the lowest levels of membrane γc among thymocytes [35], but interestingly they also expressed the highest level of sγc transcripts [18]. Immature DP thymocytes have to be shielded from pro-survival cytokine signals to ensure TCR-dependent selection of an immunocompetent repertoire [41]. Expression of suppressor of cytokine signaling-1 (SOCS-1) and termination of IL-7Rα expression are the major mechanisms to achieve this [42]. The increase of alternative γc splicing in immature DP thymocyte could potentially augment inhibition of cytokine signaling during thymocyte differentiation.

Finally, because the absence of sγc dramatically ameliorated pro-inflammatory immune responses, neutralization of sγc is an attractive strategy to improve the clinical outcome of inflammatory diseases. This approach might be effective because it can selectively target the soluble form of γc without affecting membrane γc. Conventional anti-γc antibodies bind to both membrane and soluble γc. But antibodies specific for sγc C-terminal epitopes would only bind to alternatively spliced γc proteins and could selectively neutralize pro-inflammatory sγc. The therapeutic value of conventional anti-γc antibodies has been recently demonstrated in acute and chronic GVHD models, where γc blockade with anti-γc antibodies resulted in relief of clinical symptoms and dramatically improved survival [140]. Thus, anti-γc treatment represents a viable option as a therapeutic tool. Importantly, anti-γc treatment not only targets mγc but will also neutralize serum sγc. Consequently, improved GVHD outcome might already reflect an effect of sγc neutralization.

Collectively, despite all the advances that were made in γc biology, γc keeps surprising us by continuing to reveal new aspects of its biology. The recent discovery of alternatively spliced, soluble γc generation is a prime example, and it demonstrates that γc still has more tricks in its bag to control T cell immunity.

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Alfred Singer and Xuguang Tai for critical review of this manuscript. We also thank Douglas Joubert, NIH Library Writing Center, for manuscript editing assistance. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research.

References

- 1.Rochman Y, Spolski R, Leonard WJ. New insights into the regulation of T cells by γc family cytokines. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:480–490. doi: 10.1038/nri2580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sugamura K, Asao H, Kondo M, Tanaka N, Ishii N, Ohbo K, Nakamura M, Takeshita T. The interleukin-2 receptor γ chain: its role in the multiple cytokine receptor complexes and T cell development in XSCID. Annu Rev Immunol. 1996;14:179–205. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.14.1.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Noguchi M, Yi H, Rosenblatt HM, Filipovich AH, Adelstein S, Modi WS, McBride OW, Leonard WJ. Interleukin-2 receptor γ chain mutation results in X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency in humans. Cell. 1993;73:147–157. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90167-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Puck JM, Nussbaum RL, Conley ME. Carrier detection in X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency based on patterns of X chromosome inactivation. J Clin Invest. 1987;79:1395–1400. doi: 10.1172/JCI112967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.DiSanto JP, Muller W, Guy-Grand D, Fischer A, Rajewsky K. Lymphoid development in mice with a targeted deletion of the interleukin 2 receptor γ chain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:377–381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.2.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schorle H, Holtschke T, Hunig T, Schimpl A, Horak I. Development and function of T cells in mice rendered interleukin-2 deficient by gene targeting. Nature. 1991;352:621–624. doi: 10.1038/352621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Freeden-Jeffry U, Vieira P, Lucian LA, McNeil T, Burdach SE, Murray R. Lymphopenia in interleukin (IL)-7 gene-deleted mice identifies IL-7 as a nonredundant cytokine. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1519–1526. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rodewald HR, Waskow C, Haller C. Essential requirement for c-kit and common γ chain in thymocyte development cannot be overruled by enforced expression of Bcl-2. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1431–1437. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.12.1431. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sudo T, Nishikawa S, Ohno N, Akiyama N, Tamakoshi M, Yoshida H, Nishikawa S. Expression and function of the interleukin 7 receptor in murine lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:9125–9129. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.9125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhatia SK, Tygrett LT, Grabstein KH, Waldschmidt TJ. The effect of in vivo IL-7 deprivation on T cell maturation. J Exp Med. 1995;181:1399–1409. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.4.1399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fontenot JD, Rasmussen JP, Gavin MA, Rudensky AY. A function for interleukin 2 in Foxp3-expressing regulatory T cells. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:1142–1151. doi: 10.1038/ni1263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weinreich MA, Odumade OA, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. T cells expressing the transcription factor PLZF regulate the development of memory-like CD8+ T cells. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:709–716. doi: 10.1038/ni.1898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lodolce JP, Boone DL, Chai S, Swain RE, Dassopoulos T, Trettin S, Ma A. IL-15 receptor maintains lymphoid homeostasis by supporting lymphocyte homing and proliferation. Immunity. 1998;9:669–676. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80664-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oh S, Perera LP, Burke DS, Waldmann TA, Berzofsky JA. IL-15/IL-15Rα-mediated avidity maturation of memory CD8+ T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:15154–15159. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406649101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vogelzang A, McGuire HM, Yu D, Sprent J, Mackay CR, King C. A fundamental role for interleukin-21 in the generation of T follicular helper cells. Immunity. 2008;29:127–137. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nurieva RI, Chung Y, Hwang D, Yang XO, Kang HS, Ma L, Wang YH, Watowich SS, Jetten AM, Tian Q, Dong C. Generation of T follicular helper cells is mediated by interleukin-21 but independent of T helper 1, 2, or 17 cell lineages. Immunity. 2008;29:138–149. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nurieva R, Yang XO, Martinez G, Zhang Y, Panopoulos AD, Ma L, Schluns K, Tian Q, Watowich SS, Jetten AM, Dong C. Essential autocrine regulation by IL-21 in the generation of inflammatory T cells. Nature. 2007;448:480–483. doi: 10.1038/nature05969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong C, Luckey MA, Ligons DL, Waickman AT, Park JY, Kim GY, Keller HR, Etzensperger R, Tai X, Lazarevic V, Feigenbaum L, Catalfamo M, Walsh ST, Park JH. Activated T cells secrete an alternatively spliced form of common γ-chain that inhibits cytokine signaling and exacerbates inflammation. Immunity. 2014;40:910–923. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walsh ST. Structural insights into the common γ-chain family of cytokines and receptors from the interleukin-7 pathway. Immunol Rev. 2012;250:303–316. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2012.01160.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McElroy CA, Holland PJ, Zhao P, Lim JM, Wells L, Eisenstein E, Walsh ST. Structural reorganization of the interleukin-7 signaling complex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:2503–2508. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116582109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pillet AH, Lavergne V, Pasquier V, Gesbert F, Theze J, Rose T. IL-2 induces conformational changes in its preassembled receptor core, which then migrates in lipid raft and binds to the cytoskeleton meshwork. J Mol Biol. 2010;403:671–692. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.08.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Linowes BA, Ligons DL, Nam AS, Hong C, Keller HR, Tai X, Luckey MA, Park JH. Pim1 permits generation and survival of CD4+ T cells in the absence of γc cytokine receptor signaling. Eur J Immunol. 2013;43:2283–2294. doi: 10.1002/eji.201242686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.de Saint Basile G, Arveiler B, Oberle I, Malcolm S, Levinsky RJ, Lau YL, Hofker M, Debre M, Fischer A, Griscelli C et al (1987) Close linkage of the locus for X chromosome-linked severe combined immunodeficiency to polymorphic DNA markers in Xq11–q13. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 84:7576–7579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 24.Puck JM, Nussbaum RL, Smead DL, Conley ME. X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency: localization within the region Xq13.1–q21.1 by linkage and deletion analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 1989;44:724–730. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puck JM, Deschenes SM, Porter JC, Dutra AS, Brown CJ, Willard HF, Henthorn PS. The interleukin-2 receptor γ chain maps to Xq13.1 and is mutated in X-linked severe combined immunodeficiency, SCIDX1. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:1099–1104. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.8.1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cao X, Shores EW, Hu-Li J, Anver MR, Kelsall BL, Russell SM, Drago J, Noguchi M, Grinberg A, Bloom ET, et al. Defective lymphoid development in mice lacking expression of the common cytokine receptor γ chain. Immunity. 1995;2:223–238. doi: 10.1016/1074-7613(95)90047-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gougeon ML, Drean G, Le Deist F, Dousseau M, Fevrier M, Diu A, Theze J, Griscelli C, Fischer A. Human severe combined immunodeficiency disease: phenotypic and functional characteristics of peripheral B lymphocytes. J Immunol. 1990;145:2873–2879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Matthews DJ, Clark PA, Herbert J, Morgan G, Armitage RJ, Kinnon C, Minty A, Grabstein KH, Caput D, Ferrara P, et al. Function of the interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor γ-chain in biologic responses of X-linked severe combined immunodeficient B cells to IL-2, IL-4, IL-13, and IL-15. Blood. 1995;85:38–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kennedy MK, Glaccum M, Brown SN, Butz EA, Viney JL, Embers M, Matsuki N, Charrier K, Sedger L, Willis CR, Brasel K, Morrissey PJ, Stocking K, Schuh JC, Joyce S, Peschon JJ. Reversible defects in natural killer and memory CD8 T cell lineages in interleukin 15-deficient mice. J Exp Med. 2000;191:771–780. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.5.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Penit C, Lucas B, Vasseur F. Cell expansion and growth arrest phases during the transition from precursor (CD4−8−) to immature (CD4+8+) thymocytes in normal and genetically modified mice. J Immunol. 1995;154:5103–5113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nakajima H, Leonard WJ. Role of Bcl-2 in αβ T cell development in mice deficient in the common cytokine receptor γ-chain: the requirement for Bcl-2 differs depending on the TCR/MHC affinity. J Immunol. 1999;162:782–790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kondo M, Akashi K, Domen J, Sugamura K, Weissman IL. Bcl-2 rescues T lymphopoiesis, but not B or NK cell development, in common γ chain-deficient mice. Immunity. 1997;7:155–162. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80518-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakajima H, Noguchi M, Leonard WJ. Role of the common cytokine receptor γ chain (γc) in thymocyte selection. Immunol Today. 2000;21:88–94. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5699(99)01555-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.DiSanto JP, Guy-Grand D, Fisher A, Tarakhovsky A. Critical role for the common cytokine receptor γ chain in intrathymic and peripheral T cell selection. J Exp Med. 1996;183:1111–1118. doi: 10.1084/jem.183.3.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McCaughtry TM, Etzensperger R, Alag A, Tai X, Kurtulus S, Park JH, Grinberg A, Love P, Feigenbaum L, Erman B, Singer A. Conditional deletion of cytokine receptor chains reveals that IL-7 and IL-15 specify CD8 cytotoxic lineage fate in the thymus. J Exp Med. 2012;209:2263–2276. doi: 10.1084/jem.20121505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Park JH, Adoro S, Lucas PJ, Sarafova SD, Alag AS, Doan LL, Erman B, Liu X, Ellmeier W, Bosselut R, Feigenbaum L, Singer A. ‘Coreceptor tuning’: cytokine signals transcriptionally tailor CD8 coreceptor expression to the self-specificity of the TCR. Nat Immunol. 2007;8:1049–1059. doi: 10.1038/ni1512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Akashi K, Kondo M, von Freeden-Jeffry U, Murray R, Weissman IL. Bcl-2 rescues T lymphopoiesis in interleukin-7 receptor-deficient mice. Cell. 1997;89:1033–1041. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80291-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.von Freeden-Jeffry U, Solvason N, Howard M, Murray R. The earliest T lineage-committed cells depend on IL-7 for Bcl-2 expression and normal cell cycle progression. Immunity. 1997;7:147–154. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80517-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Singer A, Adoro S, Park JH. Lineage fate and intense debate: myths, models and mechanisms of CD4- versus CD8-lineage choice. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:788–801. doi: 10.1038/nri2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Brugnera E, Bhandoola A, Cibotti R, Yu Q, Guinter TI, Yamashita Y, Sharrow SO, Singer A. Coreceptor reversal in the thymus: signaled CD4+8+ thymocytes initially terminate CD8 transcription even when differentiating into CD8+ T cells. Immunity. 2000;13:59–71. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)00008-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yu Q, Park JH, Doan LL, Erman B, Feigenbaum L, Singer A. Cytokine signal transduction is suppressed in preselection double-positive thymocytes and restored by positive selection. J Exp Med. 2006;203:165–175. doi: 10.1084/jem.20051836. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Park JH, Adoro S, Guinter T, Erman B, Alag AS, Catalfamo M, Kimura MY, Cui Y, Lucas PJ, Gress RE, Kubo M, Hennighausen L, Feigenbaum L, Singer A. Signaling by intrathymic cytokines, not T cell antigen receptors, specifies CD8 lineage choice and promotes the differentiation of cytotoxic-lineage T cells. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:257–264. doi: 10.1038/ni.1840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Puel A, Ziegler SF, Buckley RH, Leonard WJ. Defective IL7R expression in T−B+NK+ severe combined immunodeficiency. Nat Genet. 1998;20:394–397. doi: 10.1038/3877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kondo M, Takeshita T, Ishii N, Nakamura M, Watanabe S, Arai K, Sugamura K. Sharing of the interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor γ chain between receptors for IL-2 and IL-4. Science. 1993;262:1874–1877. doi: 10.1126/science.8266076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Russell SM, Keegan AD, Harada N, Nakamura Y, Noguchi M, Leland P, Friedmann MC, Miyajima A, Puri RK, Paul WE, et al. Interleukin-2 receptor γ chain: a functional component of the interleukin-4 receptor. Science. 1993;262:1880–1883. doi: 10.1126/science.8266078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kimura Y, Takeshita T, Kondo M, Ishii N, Nakamura M, Van Snick J, Sugamura K. Sharing of the IL-2 receptor γ chain with the functional IL-9 receptor complex. Int Immunol. 1995;7:115–120. doi: 10.1093/intimm/7.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Russell SM, Johnston JA, Noguchi M, Kawamura M, Bacon CM, Friedmann M, Berg M, McVicar DW, Witthuhn BA, Silvennoinen O, et al. Interaction of IL-2Rβ and γc chains with Jak1 and Jak3: implications for XSCID and XCID. Science. 1994;266:1042–1045. doi: 10.1126/science.7973658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Giri JG, Ahdieh M, Eisenman J, Shanebeck K, Grabstein K, Kumaki S, Namen A, Park LS, Cosman D, Anderson D. Utilization of the β and γ chains of the IL-2 receptor by the novel cytokine IL-15. EMBO J. 1994;13(12):2822–2830. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1994.tb06576.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asao H, Takeshita T, Ishii N, Kumaki S, Nakamura M, Sugamura K. Reconstitution of functional interleukin 2 receptor complexes on fibroblastoid cells: involvement of the cytoplasmic domain of the γ chain in two distinct signaling pathways. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4127–4131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.9.4127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noguchi M, Nakamura Y, Russell SM, Ziegler SF, Tsang M, Cao X, Leonard WJ. Interleukin-2 receptor γ chain: a functional component of the interleukin-7 receptor. Science. 1993;262:1877–1880. doi: 10.1126/science.8266077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Herrmann T, Diamantstein T. The high affinity interleukin 2 receptor: evidence for three distinct polypeptide chains comprising the high affinity interleukin 2 receptor. Mol Immunol. 1988;25:1201–1207. doi: 10.1016/0161-5890(88)90156-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arima N, Kamio M, Imada K, Hori T, Hattori T, Tsudo M, Okuma M, Uchiyama T. Pseudo-high affinity interleukin 2 (IL-2) receptor lacks the third component that is essential for functional IL-2 binding and signaling. J Exp Med. 1992;176:1265–1272. doi: 10.1084/jem.176.5.1265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nakarai T, Robertson MJ, Streuli M, Wu Z, Ciardelli TL, Smith KA, Ritz J. Interleukin 2 receptor γ chain expression on resting and activated lymphoid cells. J Exp Med. 1994;180:241–251. doi: 10.1084/jem.180.1.241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Boussiotis VA, Barber DL, Nakarai T, Freeman GJ, Gribben JG, Bernstein GM, D’Andrea AD, Ritz J, Nadler LM. Prevention of T cell anergy by signaling through the γc chain of the IL-2 receptor. Science. 1994;266:1039–1042. doi: 10.1126/science.7973657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Miyazaki T, Kawahara A, Fujii H, Nakagawa Y, Minami Y, Liu ZJ, Oishi I, Silvennoinen O, Witthuhn BA, Ihle JN, et al. Functional activation of Jak1 and Jak3 by selective association with IL-2 receptor subunits. Science. 1994;266:1045–1047. doi: 10.1126/science.7973659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kawamura M, McVicar DW, Johnston JA, Blake TB, Chen YQ, Lal BK, Lloyd AR, Kelvin DJ, Staples JE, Ortaldo JR, et al. Molecular cloning of L-JAK, a Janus family protein-tyrosine kinase expressed in natural killer cells and activated leukocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6374–6378. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.14.6374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Johnston JA, Kawamura M, Kirken RA, Chen YQ, Blake TB, Shibuya K, Ortaldo JR, McVicar DW, O’Shea JJ. Phosphorylation and activation of the Jak-3 Janus kinase in response to interleukin-2. Nature. 1994;370:151–153. doi: 10.1038/370151a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Witthuhn BA, Silvennoinen O, Miura O, Lai KS, Cwik C, Liu ET, Ihle JN. Involvement of the Jak-3 Janus kinase in signalling by interleukins 2 and 4 in lymphoid and myeloid cells. Nature. 1994;370:153–157. doi: 10.1038/370153a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Rodig SJ, Meraz MA, White JM, Lampe PA, Riley JK, Arthur CD, King KL, Sheehan KC, Yin L, Pennica D, Johnson EM, Jr, Schreiber RD. Disruption of the Jak1 gene demonstrates obligatory and nonredundant roles of the Jaks in cytokine-induced biologic responses. Cell. 1998;93:373–383. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parganas E, Wang D, Stravopodis D, Topham DJ, Marine JC, Teglund S, Vanin EF, Bodner S, Colamonici OR, van Deursen JM, Grosveld G, Ihle JN. Jak2 is essential for signaling through a variety of cytokine receptors. Cell. 1998;93:385–395. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Neubauer H, Cumano A, Muller M, Wu H, Huffstadt U, Pfeffer K. Jak2 deficiency defines an essential developmental checkpoint in definitive hematopoiesis. Cell. 1998;93:397–409. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81168-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]