Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is increasing in incidence and is projected to become the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States. Despite significant advances in understanding the disease, there has been minimal increase in PDAC patient survival. PDAC tumors are unique in the fact that there is significant desmoplasia. This generates a large stromal compartment composed of immune cells, inflammatory cells, growth factors, extracellular matrix, and fibroblasts, comprising the tumor microenvironment (TME), which may represent anywhere from 15% to 85% of the tumor. It has become evident that the TME, including both the stroma and extracellular component, plays an important role in tumor progression and chemoresistance of PDAC. This review will discuss the multiple components of the TME, their specific impact on tumorigenesis, and the multiple therapeutic targets.

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is increasing in incidence and is currently the fourth leading cause of cancer death in the United States, with an estimated incidence of 55,440 in 2018 and 44,330 deaths.1 By 2030, PDAC is predicted to surpass breast, prostate, and colon cancers to become the second leading cause of cancer death in the United States, following only lung cancer.2 PDAC comprises >90% of all pancreatic tumors and has by far the poorest prognosis of all solid tumors.3

Currently, the most promising chance of cure remains surgery, with negative margins in combination with adjuvant therapy. However, most patients present late with localized disease not amenable to surgery at the time of diagnosis. Although there have been multiple recent improvements in the treatment of PDAC, including combination chemotherapies that have improved survival, such as gemcitabine plus capecitabine in the adjuvant setting as well as in advanced disease and the use of fluorouracil, leucovorin, irinotecan and oxaliplatin (FOLFIRINOX) in advanced disease, the overall 5-year survival rate remains 8%.1, 4, 5, 6

PDAC is unique in the fact that there is a significant desmoplastic response generating a large stromal component, including immune cells, inflammatory cells, growth factors, extracellular matrix, and fibroblasts, which may represent anywhere from 15% to 85% of the tumor.7, 8, 9 This desmoplastic microenvironment may compromise tumor blood perfusion and oxygen delivery, in turn generating an obstacle for drug delivery. This barrier has been hypothesized to add to the difficulty in finding effective treatments for PDAC and lead to intrinsic resistance to chemotherapy regimens, including gemcitabine.10 Significant research efforts recently have focused on this tumor-stroma relationship, and this review serves to delineate these components and how they may be used in the pathologic setting and in developing targeted therapeutics.

Pancreatic Tumor Biology

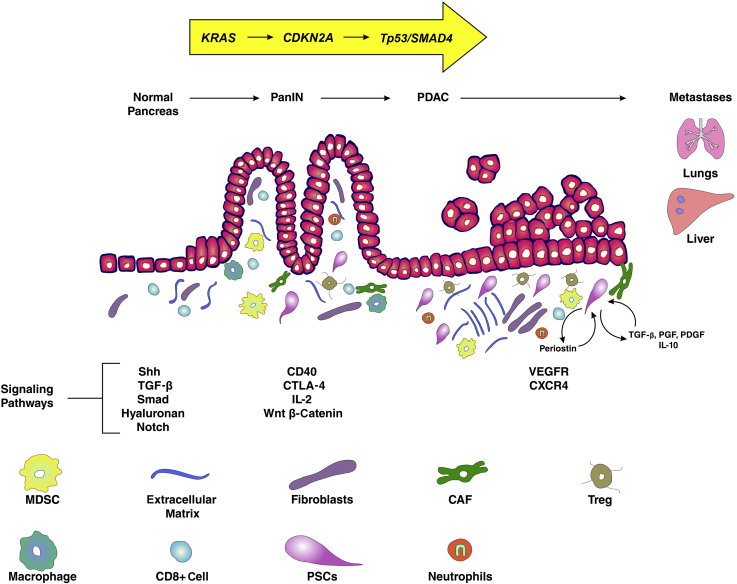

The development of PDAC has been shown to progress because of an activating mutation in the KRAS oncogene, resulting in acinar to ductal metaplasia, followed by subsequent progression through increasing grades of pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) and ultimately PDAC after acquiring additional somatic mutations in multiple tumor suppressor genes, including p16/CDKN2A, TP53, and SMAD4, and the overexpression of HER2-2/neu in mouse models.11, 12, 13, 14 The progression from acinar cell to PDAC is accompanied by a profuse fibrotic stromal desmoplasia, which is the basis of a complex tumor microenvironment (TME) (Figure 1). This microenvironment is heterogeneous and is composed of a cellular and acellular component. The cellular component includes stroma, cancer-associated fibroblasts, myofibroblasts, pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs), blood vessels, and immune cells. The acellular component is made up of collagen, fibronectin, and multiple soluble factors, including cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors residing in the extracellular matrix (ECM).7, 8, 9, 15 This microenvironment is not static and is constantly changing composition. Thus, this is a challenging system to generate in animal models. However, the LSL-KrasG12D/+;LSL-Trp53R172H/+;Pdx-1-Cre (KPC) mouse model of PDAC, introduced in 2005, recapitulates the dense stromal reaction and many of the key features of the immune microenvironment observed in human PDAC16 (Figure 2). The generation of this mouse model of PDAC has significantly advanced the study of the complex microenvironment of PDAC as well as potential therapeutic targets.

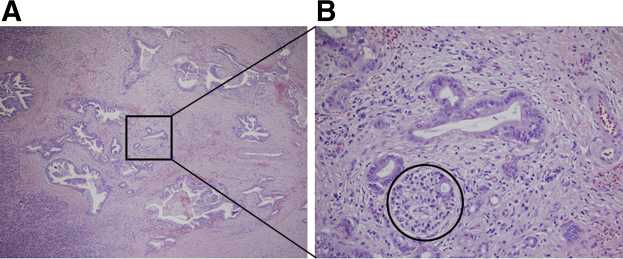

Figure 1.

A: Overview of hematoxylin and eosin section: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma with desmoplastic fibrous response. B: Desmoplastic environment, including acute and chronic inflammation. Circle indicates a partially invaded islet. Original magnification: ×4 (A); ×20 (B).

Figure 2.

Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and trichrome staining of pancreatic tumors arising in two KPC mice recapitulating the dense collagen-rich stroma seen in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma tumors. Scale bars = 100 μm.

Stroma

Pancreatic Stellate Cells

Pancreatic stellate cells, first identified in 1998 in normal rat pancreatic tissue and later in normal human pancreas, function to maintain connective tissue architecture but are quiescent.17 In the normal human pancreas, PSCs comprise approximately 4% to 7% of the parenchymal cells and contain cytoplasmic lipid droplets containing vitamin A in the quiescent state.18 When activated, PSCs play an integral role in synthesis and deposition of ECM.18

PSCs have been isolated from patients with both chronic pancreatitis and PDAC.19 Chronic inflammation of the pancreas activates PSCs, resulting in loss of vitamin A droplets, a myofibroblast-like phenotype; expression of cytoskeletal protein α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA); and deposition of excessive ECM.17, 18, 20 Activated PSCs have been identified in both human and mouse samples in regions containing pancreatic fibrosis.21

In the setting of carcinogenesis, these activated PSCs can be observed as early as in the preneoplastic PanIN stages.15, 17 Apte and colleagues18, 20 noted colocalization of α-SMA with procollagen mRNA in PDAC samples, which was the first suggestion that activated PSCs were responsible for the majority of collagen in the stroma of human PDAC tumor samples. They further showed that, in vitro, human PDAC conditioned medium resulted in activation of PSCs and an increase in proliferation of these cells.22 In this setting, the PSCs not only deposit excessive ECM, but also foster a network of inflammatory cells, acinar cells, and transformed cancer cells.19, 23, 24 Activated PSCs show differential expression of multiple genes, including an up-regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-3 by 32.25-fold and a down-regulation of the basement membrane component, collagen type IVα1 by 2.25-fold, which may contribute to their remodeling of the ECM in the activated setting.20 In addition, they secrete periostin, a cell adhesion protein that stimulates cancer cell growth and confers resistance of these cancer cells to starvation and hypoxia.25 The activated PSCs are involved in an autocrine loop with periostin, leading to an increase in collagen I, transforming growth factor-β1, and fibronectin, ultimately resulting in increased chemoresistance.20, 25

PSCs activated in the setting of carcinogenesis show an increase in proliferation and migration mediated by platelet-derived growth factor. The increased production of fibronectin and collagen I is mediated by transforming growth factor-β1 and fibroblast growth factor 2.17, 18, 21, 22 In addition, cyclooxygenase-2, expressed by PSCs, is important for the interaction between PSCs and PDAC cells. Studies using conditioned medium from cancer cells resulted in an increased expression of cyclooxygenase-2 and proliferation of PSCs. Furthermore, a cyclooxygenase-2 inhibitor prevented PSC proliferation in the same conditioned medium.26 Members of the trefoil factor (TFF) protein family, including TFF1 and TFF2, normally excreted by gastrointestinal mucosa in response to damage, are both expressed in the setting of PDAC.27, 28 TFF1 is known to stimulate proliferation of PSCs as well as PSC migration and PDAC cell invasion.26 TFF2 is known to increase PDAC cell migration via the chemokine receptor type 4, which has elevated expression in both PanINs and PDAC. It has also been implicated in metastasis via downstream activation of Akt and extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways.29

In vivo studies have shown that patients whose PDAC tumors have fibrotic foci have shorter survival than those without.30 In addition, high α-SMA/collagen ratios in pancreatic tumors have also been correlated with worse prognosis.31

Immune Component

Although the TME of PDAC is dominated by dense stroma, it is also replete with immune cells (Figure 3).32 This presence of immune cells, which can also be found in conjunction with inflammation, has been tied to the transition from normal pancreas to PDAC. This is demonstrated by the increased incidence of PDAC reported in patients with chronic pancreatitis.33 Chronic inflammation in these patients is postulated to occur because of persistent activation of the immune response after release of inflammatory mediators, including IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α.34 These immunoinflammatory cells exhibit altered function and ultimately result in production of immunosuppressive signals, as well as inflammatory cytokines that promote tumor progression and invasion.35 Specifically, M2 tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs), and regulatory T cells appear in precursor lesions of PDAC and persist through invasive cancer, inducing immunosuppression in mouse models.36

Figure 3.

Depiction of the pancreatic tumor microenvironment throughout progression from pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia (PanIN) to pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC). CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4; CXCR4, chemokine receptor type 4; MDSC, myeloid-derived suppressor cell; PDGF, platelet-derived growth factor; PGF, prostaglandin F; PSC, pancreatic stellate cell; Shh, sonic hedgehog; TGF-β, transforming growth factor-β; Treg, regulatory T cell; VEGFR, vascular endothelial growth factor receptor.

Tumor-Associated Macrophages

TAMs have been identified in many tumor types, and the distribution is associated with prognosis. In PDAC, tumor cells induce differentiation and education of the macrophages to the M2 phenotype (characterized by CD163 and CD204), and in turn, enhance the progression of tumor growth, angiogenesis, and metastasis.37, 38 TAMs have been studied as a therapeutic target in several tumor types, including PDAC. A phase 2 trial targeting TAMs with trabectedin in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer was recently completed (www.clinicaltrials.gov; trial identifier NCT01339754). Trabectedin causes caspase-8–dependent apoptosis and expression of receptors in macrophages, ultimately targeting mononuclear phagocytes.39 There are multiple other potential therapeutic targets of TAMs, including colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor, which is expressed by macrophages. Blockade of colony-stimulating factor 1 receptor in mouse models reprogrammed the TAMs and enhanced antigen presentation as well as antitumor T-cell immune responses.40 Decoy receptor 3, also referred to as tumor necrosis factor receptor superfamily member 6b, is overexpressed in PDAC, and therefore is an additional therapeutic candidate. Expression of decoy receptor 3 is inversely correlated with survival in PDAC.41 Decoy receptor 3 down-regulates expression of major histocompatibility complex-II and human leukocyte antigen-DR on macrophages, making it a potential target to modulate macrophages in PDAC.42, 43 There needs to be additional preclinical studies done with these potential targets.

Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells

MDSCs are a mixture of immature myeloid cells and comprise two types of cells, polymorphonuclear granulocytic MDSCs and mononuclear monocytic MDSCs. However, identification remains difficult because of their lack of defining surface markers. Tumor cell production of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor attracts immature myeloid cells and skews differentiation toward MDSCs. The MDSCs then suppress both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, mitigating the CD8+ T-cell immune surveillance, and allow for expansion of immunosuppressive regulatory T cells.36 MDSCs increase as PDAC progresses from preinvasive lesions to invasive disease in mouse models, and circulating levels have been correlated to a more advanced stage in human PDAC patients.35 Thus, the inhibition of MDSCs is a potential therapeutic target in PDAC. Selective depletion of granulocytic MDSCs in mouse models enhances apoptosis of tumor cells with an increased infiltration of CD8+ T cells.44 There are various methods to inhibit MDSCs in patients with PDAC that need to be further explored.

Tumor-Infiltrating T Cells

The stroma of PDAC is rich in CD3+ T lymphocytes, of which the major components are CD4+ helper T (Th) cells, CD8+ T cells, and CD4+CD25+forkhead box P3 regulatory T cells.45 CD4+ T cells, which are found in pancreatic tumors, promote PanIN formation and KRAS-driven PDAC development by secreting IL-17, suppressing the antitumor activity of CD8+ T cells.46 These CD4+ Th cells differentiate into two subsets of cells, Th1 and Th2. Th1 cells secrete IL-2 and interferon-γ, responsible for the cell-mediated immune response. Th2 cells secrete IL-4, IL-5, IL-9, IL-10, and IL-13 and are implicated in the humoral immune response.47 Th1 cells are involved in tumor-killing responses; however, Th2 cells, which are more abundant in PDAC, are tumor promoting. De Monte et al48 showed that elevated Th2/Th1 ratios within the tumor-infiltrating cells are a negative survival marker in patients with stage IIB/III pancreatic cancer. There are multiple CD4+ T-cell targets as well as targets against the multiple cytokines mentioned above that are beyond the scope of this review.

Recently, T-cell immunity has been noted in tumors of long-term PDAC survivors.49 This concept was explored in detail by Balachandran et al,49 who showed tumors with the highest neoantigen number as well as the most abundant CD8+ T-cell infiltrates were associated with the longest-term PDAC survivors. They found neoantigen-rich hotspots, including MUC16, that will allow future research using directed neoantigen targeting as a potential therapy.

Extracellular Matrix

The acellular component of stroma (alias, the ECM) comprises 90% of the PDAC tumor mass. The ECM is composed of collagen, fibronectin, and multiple soluble factors, including cytokines, chemokines, and growth factors secreted by PSCs. These factors provide structural support and promote differentiation, remodeling, and carcinogenesis. In vitro, collagen I promotes proliferation, migration, and adhesion of PDAC cells.50 It has also been shown to interact with both collagen IV and integrin receptors on the surface of PDAC cells, promoting proliferation, maintaining a migratory phenotype, and avoiding apoptosis.51

The various components of the TME work in concert to maintain tumor integrity, survival, and propagation. There are a slew of targets that are actively under investigation that aim to induce tumor regression and prolong patient survival.

Clinical Targets of the TME

Hedgehog

The hedgehog pathway, although not expressed in the developing pancreas, is activated in premalignant lesions as well as PDAC tumors.52 This pathway is active in embryonic development as well as stem cell regulation. The hedgehog ligand, sonic hedgehog, is expressed in increasing amounts as premalignant pancreatic lesions progress.53 The hedgehog ligand activates the PSCs via paracrine effects, contributing to the increase in stroma and ultimately tumor progression.54 Specifically, pancreatic cancer cells produce sonic hedgehog, which, in turn, binds to its receptor on PSCs, Patched1, and activates intracellular signaling by removing the inhibitory effects of smoothened, leading to activation and translocation of the transcription factor Gli1 into the nucleus. Gli1 regulates genes implicated in cell differentiation, proliferation, and apoptosis found in extracellular matrix proteins.55 These now activated PSCs deposit extracellular matrix proteins, resulting in a thick stroma that inhibits access to therapeutic agents.56

The hedgehog pathway was thus an attractive target for treatment, and multiple strategies for interrupting the pathway have been tested in an attempt to deplete the stroma. There have been several preclinical studies using hedgehog targeting in pancreatic cancer. Alkaloid cyclopamine and its derivatives, including IPI-926, smoothened antagonists, and 5E1 sonic hedgehog blocking antibodies, have all been studied.56, 57 The most promising targeted therapy, IPI-926, is a semisynthetic small-molecule inhibitor derivative of the alkaloid cyclopamine that inhibits the hedgehog pathway by binding to and inhibiting Smoothened and thus keeping Gli inactive.58 Olive et al,59 in an exciting preclinical study, showed IPI-926 enhanced perfusion of gemcitabine within the pancreatic tumor and improved survival. In this study, IPI-926 decreased collagen 1 in the stroma and proliferation of α-SMA stromal cells and transiently increased blood vessel density in the tumors using a KPC mouse model.59 Early-phase studies, however, failed to show a sustained benefit in humans.60 This outcome was similar to multiple other hedgehog-targeted agents, which showed promise in preclinical studies, but failed to improve survival in early clinical trials.

Secreted Protein Acidic and Rich in Cysteine

Secreted protein acidic and rich in cysteine (SPARC; alias osteonectin) is a glycoprotein secreted by osteoblasts during bone formation. It binds calcium-initiating mineralization and promotes mineral crystal formation. In the setting of PDAC, SPARC is an extracellular protein expressed in the stroma, implicated in worse prognosis. In preclinical studies, SPARC showed a high affinity for nab-paclitaxel, which is paclitaxel conjugated with albumin nanoparticles in an attempt to increase delivery to the pancreas. Nab-paclitaxel is now used in combination with gemcitabine as the standard of care in the adjuvant setting.61 This enhanced binding of nab-paclitaxel to the SPARC-rich stroma is thought to increase delivery of the drug to tumor cells. In these studies, nab-paclitaxel, given in combination with gemcitabine, acted directly on stromal cells, resulting in stromal depletion. In addition, increased blood vessel diameter and increased expression of Nestin, an endothelial cell marker, were noted. These findings ultimately resulted in increased efficacy of gemcitabine.5, 61 Furthermore, in clinical trials using gemcitabine in combination with nab-paclitaxel, increased expression of SPARC in tumor tissue was correlated with improved median overall survival compared with those with minimal SPARC expression.62, 63 However, recently, new data show nab-paclitaxel is also effective in SPARC-deficient models, suggesting its effect may not be entirely dependent on stroma targeting and thus requires more studies to delineate the mechanism.64

Connective Tissue Growth Factor

Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) is a profibrotic extracellular protein expressed in the stroma of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Increased expression of CTGF has been documented in chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic adenocarcinoma.65, 66 In the setting of PDAC, expression is mediated by chemokine signaling through CXC proteins. These proteins then bind to growth factors and integrins, which promote fibrosis, collagen deposition, cancer progression, and metastasis.67, 68 In addition, CTGF simulates PSC proliferation and ECM protein production in the PDAC stroma.

Thus, CTGF became a promising therapeutic target for the treatment of PDAC. The monoclonal antibody, FG-3019, as well as multiple antagonists that block the interaction of CTGF with its receptor, including SB225002, were effective in preclinical studies in improving tumor response to chemotherapy as well as increasing survival in murine models.69, 70 Neesse et al70 showed increased rates of tumor cell apoptosis when FG-3019 was combined with gemcitabine in mouse models. Although the gross appearance of the tumor stroma was unchanged in these studies, there was significant down-regulation of both prosurvival and antiapoptotic proteins, including Psen1, Ubqln2, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, Birc6, and X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis.70 There are currently ongoing phase 1/2 trials looking at the efficacy of FG-3019 in conjunction with gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel (NCT02210559) in advanced unresectable pancreatic cancer.

Hyaluronan

Hyaluronan (HA) is a nonsulfated polysaccharide glycosaminoglycan found in the PDAC stromal matrix. HA in collaboration with collagens generate the fibrotic desmoplasia seen in pancreatic tumors.71 The structure of HA includes multiple anionic repeats that serve to sequester cations, resulting in osmotic swelling and providing additional support to these tissues.72 High levels of HA in PDAC tumors are associated with increased interstitial fluid pressure and desmoplasia, which together generate a barrier to perfusion and, as a result, inhibit systemic drug delivery.72, 73, 74 HA binds to CD44, a hayldaherin which regulates receptor tyrosine kinase and, in turn, impedes intratumoral angiogenesis and induces chemoresistance.75 HA is also found in metastatic PDAC lesions.71

Because of these previously mentioned findings, HA is a promising therapeutic target in the treatment of PDAC. PEGylated human recombinant PH20 hyaluronidase (PEGPH20), an enzyme that degrades hyaluronan, has had promising results in both mouse and human phase 1 and 2 trials. In these early-phase studies, PEGPH20 increased tumor vascular patency, leading to improved delivery of gemcitabine, albeit transiently.59, 75, 76, 77 In NCT01453153, patients with advanced PDAC treated with a combination of gemcitabine and PEGPH20 had improved overall as well as progression-free survival compared with patients treated with gemcitabine alone.76 When stratified by level of HA expression in tumor samples, those with high HA benefitted the most. However, thrombotic events were common in this study and, thus, going forward, anticoagulants were given in the combination.76 This trial prompted the investigation of PEGPH20 with other agents, including gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel (NCT02715804 and NCT01839487) and FOLFIRINOX (S1313/NCT01959139), which just closed accrual in July 2017. Hingorani et al78 recently published results from the phase 2 study examining PEGPH20 in combination with gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel in patients with advanced PDAC. In patients with HA high tumors (>50% HA staining of tumor surface), progression-free survival was significantly improved in those treated with the PEGPH20; and median overall survival was 11.5 versus 8.5 months for patients treated with PEGPH20, gemcitabine, and nab-paclitaxel versus those treated with gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel alone.

The incremental successes and failures thus far with both PEGPH20 and hedgehog inhibitors, respectively, targeting stromal depletion as a treatment for pancreatic cancer suggest a need to further study the tumor-stromal biology. It is thought that the stroma, in addition to generating a physical barrier to therapies, may also have tumor suppressive properties. This idea is routed in the finding that permanent stroma depletion results in a more aggressive tumor.79, 80 Thus, stroma modulation rather than depletion may prove the key to developing effective targeted therapies.

Vitamins A and D

A hallmark of activated PSCs in PDAC is a loss of retinol-storing cytoplasmic lipid droplets.17 The treatment of -activated PSCs in culture as well as in PDAC mouse models with vitamin A analogs reduced paracrine signaling of PSCs via restoration of secreted frizzled-related protein 4 and ultimately down-regulation of Wnt–β-catenin signaling. This ultimately resulted in reduced proliferation, migration, and invasion of cancer cells.81

This finding leads to similar preclinical trials using vitamin D after transcriptome analysis of human PSCs, which found high levels of vitamin D receptor. The activation of vitamin D receptor resulted in a reprogramming of the stroma through a dormant, less tumorigenic phenotype of PSCs.82 PDAC mouse models treated with a combination of calcitriol, a vitamin D analog, and gemcitabine lead to a less inflammatory, more quiescent stroma; enhanced delivery of the gemcitabine; and improved survival than those treated with gemcitabine alone.82 There are currently five active clinical trials looking at vitamin D analogs in combination with other chemotherapy or targeted drugs for the treatment of early as well as late PDAC (NCT02930902, NCT03300921, NCT03331562, NCT02030860, and NCT03138720).

Pirfenidone

Pirfenidone, a known antifibrotic agent originally used to treat pulmonary fibrosis, decreases the expression of several fibrosis mediators, including transforming growth factor-β and collagen. In in vitro studies, treatment with pirfenidone decreased PSC proliferation, invasion, migration, ECM components, and tumor growth. This was evident from decreased expression of platelet-derived growth factor-A, periostin, hepatocyte growth factor, fibronectin, and collagen type I in PSCs.83 In this study, there was also decreased α-SMA, indicating inhibited PSC activation.83 In preclinical studies, pirfenidone given with gemcitabine reduced tumor growth compared with gemcitabine alone.83 Pirfenidone has also been studied in combination with chemotherapeutic drugs, such as gemcitabine in the form of β-cyclodextrin matrix metalloproteinase-2 responsive liposome, where it more efficiently targeted the delivery of the drugs to the tumor cells and increased perfusion of the chemotherapy agents to the tumors.84 However, this has not been validated in preclinical models yet. Pirfenidone has also been combined with N-acetyl cysteine in preclinical models, resulting in decreased stroma and increased drug efficacy.85 There are currently no trials registered using pirfenidone in the setting of PDAC.

Angiotensin Inhibitors

Angiotensin inhibitors, such as olmasartan and losartan, used currently for treatment of hypertension, have shown some promise in pancreatic cancer. Angiotensin II has been shown to stimulate PSC proliferation, migration, and ECM production through protein kinase C and the epidermal growth factor–extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathways.86, 87 This finding prompted multiple preclinical studies using angiotensin inhibitors. Masamune et al88 demonstrated that olmesartan reduced the activated PSC marker, α-SMA, and collagen deposition as well as decreased tumor growth in mouse models. Similarly, losartan reduced the density of α-SMA–positive cells, decreased collagen and hyaluronan expression, enhanced chemotherapy efficacy, and attenuated hypoxia in orthotopic mouse models.89 This was thought to be mediated through transforming growth factor-β1, CTGF, and endothelin-1, all of which control PSC production of ECM. There is a currently accruing phase 2 trial looking at FOLFIRINOX in combination with losartan before radiation therapy versus FOLFRINIOX and radiation therapy alone to evaluate the role of losartan as a chemotherapy sensitizer in PDAC patients (NCT01821729).

There are conflicting data from a study that used a -syngeneic orthotopic mouse model with angiotensin II receptor deficiency in pancreatic fibroblasts. The tumors in these angiotensin receptor 2 knockout mice grew larger compared with -control wild-type mice.90 This was followed up with co-culture of angiotensin receptor 2 overexpressing fibroblasts with pancreatic cancer cells, which resulted in vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)–mediated attenuation of cancer cell growth.90 These conflicting results suggest a need for further studies investigating the role of angiotensin II in the PDAC stroma, which will hopefully be elucidated in the current ongoing preclinical and clinical trials.

Hypoxia and Angiogenesis

The dense stroma of PDAC in combination with accumulation of ECM proteins result in impaired tumor vasculature and hypoxia.91 In response, PDAC cells have adapted to this hypoxic environment, resulting in hypoxic resistant tumor cells. As a result, this generates a barrier to pharmacodelivery. Thus, hypoxia-activated cytotoxic prodrugs, such as TH-302, are attractive targets. TH-302 is a 2-nitroimidazole prodrug that is activated only under hypoxic conditions, resulting in the radical anion to undergo irreversible fragmentation, releasing the active drug, which is an alkylating cytotoxic agent.92 TH-302 in combination with gemcitabine improved progression-free survival in preclinical mouse models.92 Phase 2 trials supported the preclinical data, with progression-free survival, tumor response, and CA19-9 response all significantly improved with gemcitabine plus TH-302 in patients with advanced PDAC.93 This combination has now moved on to phase 3 trials (NCT01746979).

Angiogenesis is imperative for progression of all tumor types; therefore, it is a potential therapeutic target. One of the most well-studied therapeutic targets of angiogenesis is VEGF. Bevacizumab, an anti-VEGF antibody, has shown significant benefits in the treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. However, a phase 3 trial looking at bevacizumab given with gemcitabine, which included patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, showed no survival benefit.94 Thus, the role of VEGF in angiogenesis in the setting of PDAC must be further delineated to use it successfully as a therapeutic target.

In addition to VEGF, the hepatocyte growth factor–c-MET pathway has also been implicated in tumor angiogenesis. In the setting of the PDAC TME, PSCs secrete hepatocyte growth factor, which binds to receptor c-Met on cancer cells, leading to dimerization and phosphorylation of the receptor and downstream signaling, resulting in proliferation and migration of PDAC cells.95 The inhibition of this pathway with a neutralizing antibody, INC280, decreased neoangiogenesis and decreased tumor growth in xenogenic and syngeneic mouse models when given alone as well as in combination with gemcitabine.96 Treatment with INC280 proved to block metastases better than gemcitabine, but this effect was lost when given in combination.96 There is currently a phase 1 trial looking at a combination of gemcitabine, nab-paclitaxel, and ficlatuzumab (AV-299), a hepatocyte growth factor monoclonal antibody in patients with advanced PDAC; however, there are no results yet (NCT 03316599).

Focal Adhesion Kinase

Focal adhesion kinases (FAKs), including FAK1 and PYSK2 (FAK2), are nonreceptor tyrosine kinases elevated in human PDAC tissue, and they correlate with increased fibrosis as well as poor CD8+ cytotoxic T-cell infiltration.97 The inhibition of FAK in combination with VS-4718 limited tumor progression and increased survival in KPC mice associated with reduced tumor fibrosis and decreased tumor-infiltrating immunosuppressive cells. In addition, the inhibition of FAK in these mice sensitized previously unresponsive tumors to T-cell immunotherapy and programmed cell death 1 receptor (PD-1) agonists.97 A phase 1 study of VS-4718 is currently suspended because of funding (NCT0265172); however, multiple other studies looking at FAK inhibitors in combination with PD-1 (NCT02758587), trametinib (NCT02428270), pembrolizumab, and gemcitabine (NCT02546531) are still active.

Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway

Wnt/β-catenin signaling is crucial for normal embryonic development and the maintenance of adult tissue. Dysregulation of this signaling pathway leads to initiation and progression of multiple cancers, including PDAC, as well as aggressive tumor biology.98, 99, 100 Wnt pathway activation is observed in up to 65% of PanINs and increased even more frequently in invasive PDAC.101, 102, 103 Several Wnt/β-catenin inhibitors have shown success in vivo and are now in preclinical trials. One example, PRI-724, a second-generation molecule that targets coactivators CBP and P300 by inhibiting expression of the apoptosis inhibitor BIRC5, is currently in clinical trials in patients with advanced or metastatic PDAC as an adjunct to gemcitabine (NCT01764477).104

Immune Cells

Inflammation and the resulting immune response have long been thought to play a role in PDAC, given the fact that chronic pancreatitis is a risk factor for developing PDAC. Many immune costimulatory factors and checkpoint regulators have been implicated in PDAC and are part of the stroma. However, unlike in other tumor types, there has been little clinical success with immunotherapy in PDAC, possibly because of the hypoxic and, therefore, immunosuppressive environment resulting from the dense stroma. Despite this, the role of inflammation and immune response in disease progression is currently being studied.

CD40, a cell surface molecule and member of the tumor necrosis factor receptor family, plays a role in immune regulation, apoptosis, and the production of macrophage-dependent antitumor T-cell immunity.105, 106, 107 In KPC mouse models, CD40 monoclonal antibody alone as well as with gemcitabine resulted in tumor regression in 30% of mice compared with none of the mice treated with gemcitabine alone.105 The mechanism of tumor regression in these mice was macrophage-mediated depletion of the stroma through caspase-3 induction and decreased collagen I content. In phase 1 clinical trials, a combination of a CD40 agonist, CP-870, with gemcitabine in advanced PDAC patients resulted in a partial response in 18% of patients and an increase in progression-free survival and median overall survival compared with those treated with gemcitabine alone. Post-treatment biopsies of patients treated with CP-870 and gemcitabine, interestingly, showed a lack of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and abundant macrophages.105

PD-1 binds to PD-1 ligands PD-L1 and PD-L2, resulting in activation and suppression of T-cell activity and allowing for immune escape of tumor cells in the TME. Both PD-1 and PD-L1 are expressed in some PDAC tumors and are associated with poor prognosis.108 Although targeting PD-1 and PD-L1 has been successful in other tumor types, clinical trials in PDAC did not demonstrate significant response as a monotherapy.108, 109 However, there are multiple trials using PD-1 and PD-L1 in combination with other drugs. Targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4, another protein receptor that acts as an immune checkpoint expressed in PDAC, with anti–cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4 antibody ipilimumab also showed promise in mouse models, with improved survival; however, this treatment failed to show the same results in phase 2 trials.79, 110

Recently, the success of PD-1 blockade has been linked to mismatch repair deficiency.111, 112 A phase 2 study, reported by Le et al,112 showed patients with mismatch repair–deficient colorectal cancer had a significantly increased immune-related objective response and immune-related progression-free survival compared with mismatch repair–proficient colorectal cancers (40% and 78% versus 0% and 11%, respectively).

Mismatch repair–deficient noncolorectal cancers demonstrated similar results, with an immune-related objective response rate of 71% and an immune-related progression-free survival rate of 67%. The reasons for the disappointing results of PD-1 blockade in clinical trials may be because of the fact that only 2% of pancreatic cancers have mismatch repair deficiency.111

Another postulated reason for the disappointing results of PD-1, PD-L1, and immune checkpoint inhibitors is CXCL12. CXCL12 is a ligand for chemokine receptor type 4, secreted by cancer-associated fibroblasts, which ultimately binds to tumor cells, resulting in the depletion of CD8+ T cells and generating an immunosuppressive environment. In studies in which cancer-associated fibroblasts were depleted and CXCL12 delivery was targeted by a competitive blocker, cytotoxic T cells were increased within the stroma and PDAC tumor growth was inhibited.113 Administration of a chemokine receptor type 4 inhibitor, plerixafor (AMD3100), in KPC mice induced a rapid T-cell response and acted synergistically with PD-L1 antibody to inhibit tumor growth.113 Thus, the combination of immune checkpoint inhibitors with targeted drugs, such as the chemokine receptor type 4 inhibitor, which reverses immunosuppression in the TME in animal models, is an attractive therapeutic regimen and is currently being investigated in clinical trials. One such trial is the phase 1 study, NCT02301130, looking at mogamulizumab in combination with durvalumab as well as tremelimumab in advanced solid tumors, including PDAC.

Conclusions

The TME, including the stroma and extracellular component, clearly plays an important role in the progression and chemoresistance of PDAC. Although there have been many promising targets against PDAC taking advantage of the TME that have made it to early clinical trials (Table 1), none has borne out to significantly improve clinical outcomes or become standard of care. Multiple targeted approaches are currently under investigation, which will potentially provide a better combination of stromal depletion, drug delivery, and immune modulation, and thus make strides in prolonging survival in patients with PDAC.

Table 1.

Summary of Clinical Trials Targeting PDAC Tumor Microenvironment

| Intervention | Target | Phase | Trial identifier | Status | Results | Starting date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GDC-0449 (vismodegib) + gemcitabine | Hedgehog | 2 | NCT01064622 | Completed | No significant difference in response rates, OS, or PFS | 2010 |

| PRI-724 | Wnt–β-catenin | 1b | NCT01764477 | Completed | No dose-limiting toxicity in pancreatic cancer trial, some evidence of clinical activity | 2015 |

| Nab-paclitaxel + gemcitabine | Nanoparticle albumin–bound paclitaxel | 1/2 | NCT00398086 | Completed | Response rate of 48%, median OS of 12.2 months | 2006 |

| PEGPH20 + gemcitabine | HA | 1/2 | NCT01453153 | Completed | Improved PFS and OS (abstract only) | 2011 |

| PEGPH20 + gemcitabine + nab-paclitaxel | HA | 3 | NCT02715804 | Recruiting | Response rate and PFS significantly improved in patients with HA high tumors | 2016 |

| PEGPH20 + FOLFIRINOX | HA | 1/2 | NCT01959139 | Active, not recruiting | Decreased OS (abstract only) | 2013 |

| Bevacizumab + gemcitabine | VEGF-A | 3 | NCT00088894 | Completed | No difference in PFS or OS | 2004 |

| Axitinib + gemcitabine | Tyrosine kinase | 3 | NCT00471146 | Discontinued for futility | No difference in OS | 2007 |

| MK0752 + gemcitabine | γ Secretase | 1/2 | NCT01098344 | Completed | 13 of 19 patients with stable disease, 1 of 19 patients with response | 2010 |

| RO4929097 | γ Secretase | 2 | NCT01232829 | Completed | Well tolerated, but production discontinued by company | 2010 |

| RO4929097 + cediranib maleaate | γ Secretase + VEGF | 1 | NCT01131234 | Completed | No results reported | 2010 |

| Ipilimumab | CTLA-4 | 2 | NCT00112580 | Completed | No results reported | 2005 |

| CP-870,893 + gemcitabine | CD40 | 1 | NCT00711191 | Completed | Well tolerated but no phase 2 trial initiated | 2008 |

| Trabectendin | FUS-CHOP | 2 | NCT01339754 | Completed | No difference in OS | 2011 |

| IPI-926 + FOLFIRINOX | Hedgehog | 1 | NCT01383538 | Completed | Closed early because of poor results from NCT01130142 | 2011 |

| IPI-926 + gemcitabine | Hedgehog | 1b/2 | NCT01130142 | Completed | Decreased median OS and PFS | 2010 |

| FG-3019 (pamrevlumab) + gemcitabine + nab-paclitaxel | CTGF | 1/2 | NCT02210559 | Active, not recruiting | Trend toward increased resectability (abstract only) | 2014 |

| Pembrolizumab + paricalcitriol | PD-1 + vitamin D receptor | 1 | NCT02930902 | Recruiting | Still recruiting | 2016 |

| Paricalcitriol | Vitamin D receptor | 1b | NCT03300921 | Recruiting | Still recruiting | 2017 |

| Pembrolizumab + paricalcitriol | PD-1 + vitamin D receptor | 2 | NCT03331562 | Recruiting | Still recruiting | 2017 |

| Paricalcitriol + gemcitabine + nab-paclitaxel | Vitamin D receptor | 1 | NCT02030860 | Active, not recruting | No results reported | 2014 |

| Paclitaxel protein bound + gemcitabine + cisplatin + paricalcitol (neoajuvant) | Vitamin D | 2 | NCT03138720 | Recruiting | Still recruiting | 2017 |

| Losartan + FOLFIRINOX (neoadjuvant) | Angiotensin receptor (TGF-β1) | 2 | NCT01821729 | Active, not recruting | 61% R0 resection rate (abstract only) | 2013 |

| TH302 + gemcitabine | Hypoxia | 2 | NCT01144455 | Completed | Significantly increased PFS | 2010 |

| TH302 + gemcitabine | Hypoxia | 3 | NCT01746979 | Completed | Not reported yet | 2012 |

| AV-299 (ficlatuzumab) + gemcitabine + nab-paclitaxel | Hepatocyte growth factor | 1 | NCT03316599 | Recruiting | Still recruiting | 2017 |

| VS-4718 | FAK | 1 | NCT02651727 | Terminated (company stopped development) | Terminated (company stopped development) | 2016 |

| Defactinib + pembrolizumab | FAK + PD-1 | 1/2A | NCT02758587 | Recruiting | Still recruiting | 2016 |

| GSK2256098 + trametinib | FAK + MEK | 2 | NCT02428270 | Active, not recruiting | 10 of 11 with progressive disease, 1 of 11 with stable disease (abstract only) | 2015 |

| Defactinib + pembrolizumab + gemcitabine | FAK + PD-1 | 1/2 | NCT02546531 | Recruiting | Not reported yet | 2015 |

| Mogamulizumab + MEDI4736 (durvalumab) and mogamulizumab + tremelimumab | CTLA-4 + PD-1 + CCR4 | 1 | NCT02301130 | Completed | Not reported yet | 2004 |

Clinical trial descriptions may be found at https://clinicaltrials.gov.

CHOP, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, and prednisone; CTGF, connective tissue growth factor; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T-lymphocyte–associated protein 4; FAK, focal adhesion kinase; HA, hyaluronan; OS, overall survival; PD-1, programmed cell death 1 receptor; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; PEGPH20, PEGylated human recombinant PH20 hyaluronidase; PFS, progression-free survival; TGF-β1, transforming growth factor-β1; VEGF, vascular endothelial growth factor.

Footnotes

Pancreatic Cancer Theme Issue

Supported by National Cancer Institute/NIH grant NIH 5K12CA001727-20 (L.G.M.).

Disclosures: None declared.

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

This article is a part of a review series on benign and neoplastic pancreatic lesions from their pathologic to molecular profiles and diagnoses.

Supplemental material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajpath.2018.09.009.

Supplemental Data

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2018. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahib L., Smith B.D., Aizenberg R., Rosenzweig A.B., Fleshman J.M., Matrisian L.M. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74:2913–2921. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ying H., Dey P., Yao W., Kimmelman A.C., Draetta G.F., Maitra A., DePinho R.A. Genetics and biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Genes Dev. 2016;30:355–385. doi: 10.1101/gad.275776.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Neoptolemos J.P., Palmer D.H., Ghaneh P., Psarelli E.E., Valle J.W., Halloran C.M., Faluyi O., O'Reilly D.A., Cunningham D., Wadsley J., Darby S., Meyer T., Gillmore R., Anthoney A., Lind P., Glimelius B., Falk S., Izbicki J.R., Middleton G.W., Cummins S., Ross P.J., Wasan H., McDonald A., Crosby T., Ma Y.T., Patel K., Sherriff D., Soomal R., Borg D., Sothi S., Hammel P., Hackert T., Jackson R., Buchler M.W., European Study Group for Pancreatic Cancer Comparison of adjuvant gemcitabine and capecitabine with gemcitabine monotherapy in patients with resected pancreatic cancer (ESPAC-4): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;389:1011–1024. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32409-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Von Hoff D.D., Ervin T., Arena F.P., Chiorean E.G., Infante J., Moore M., Seay T., Tjulandin S.A., Ma W.W., Saleh M.N., Harris M., Reni M., Dowden S., Laheru D., Bahary N., Ramanathan R.K., Tabernero J., Hidalgo M., Goldstein D., Van Cutsem E., Wei X., Iglesias J., Renschler M.F. Increased survival in pancreatic cancer with nab-paclitaxel plus gemcitabine. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1691–1703. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1304369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Conroy T., Desseigne F., Ychou M., Bouche O., Guimbaud R., Becouarn Y., Adenis A., Raoul J.L., Gourgou-Bourgade S., de la Fouchardiere C., Bennouna J., Bachet J.B., Khemissa-Akouz F., Pere-Verge D., Delbaldo C., Assenat E., Chauffert B., Michel P., Montoto-Grillot C., Ducreux M., Groupe Tumeurs Digestives of Unicancer. PRODIGE Intergroup FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:1817–1825. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1011923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chu G.C., Kimmelman A.C., Hezel A.F., DePinho R.A. Stromal biology of pancreatic cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2007;101:887–907. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Korc M. Pancreatic cancer-associated stroma production. Am J Surg. 2007;194:S84–S86. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2007.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kota J., Hancock J., Kwon J., Korc M. Pancreatic cancer: stroma and its current and emerging targeted therapies. Cancer Lett. 2017;391:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang C., Shi S., Meng Q., Liang D., Ji S., Zhang B., Qin Y., Xu J., Ni Q., Yu X. Complex roles of the stroma in the intrinsic resistance to gemcitabine in pancreatic cancer: where we are and where we are going. Exp Mol Med. 2017;49:e406. doi: 10.1038/emm.2017.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DiGiuseppe J.A., Hruban R.H., Goodman S.N., Polak M., van den Berg F.M., Allison D.C., Cameron J.L., Offerhaus G.J. Overexpression of p53 protein in adenocarcinoma of the pancreas. Am J Clin Pathol. 1994;101:684–688. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/101.6.684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moskaluk C.A., Hruban R.H., Kern S.E. p16 and K-ras gene mutations in the intraductal precursors of human pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Res. 1997;57:2140–2143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wilentz R.E., Geradts J., Maynard R., Offerhaus G.J., Kang M., Goggins M., Yeo C.J., Kern S.E., Hruban R.H. Inactivation of the p16 (INK4A) tumor-suppressor gene in pancreatic duct lesions: loss of intranuclear expression. Cancer Res. 1998;58:4740–4744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wilentz R.E., Iacobuzio-Donahue C.A., Argani P., McCarthy D.M., Parsons J.L., Yeo C.J., Kern S.E., Hruban R.H. Loss of expression of Dpc4 in pancreatic intraepithelial neoplasia: evidence that DPC4 inactivation occurs late in neoplastic progression. Cancer Res. 2000;60:2002–2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feig C., Gopinathan A., Neesse A., Chan D.S., Cook N., Tuveson D.A. The pancreas cancer microenvironment. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:4266–4276. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-11-3114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hingorani S.R., Wang L., Multani A.S., Combs C., Deramaudt T.B., Hruban R.H., Rustgi A.K., Chang S., Tuveson D.A. Trp53R172H and KrasG12D cooperate to promote chromosomal instability and widely metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma in mice. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:469–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bachem M.G., Schneider E., Gross H., Weidenbach H., Schmid R.M., Menke A., Siech M., Beger H., Grunert A., Adler G. Identification, culture, and characterization of pancreatic stellate cells in rats and humans. Gastroenterology. 1998;115:421–432. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70209-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Apte M.V., Haber P.S., Darby S.J., Rodgers S.C., McCaughan G.W., Korsten M.A., Pirola R.C., Wilson J.S. Pancreatic stellate cells are activated by proinflammatory cytokines: implications for pancreatic fibrogenesis. Gut. 1999;44:534–541. doi: 10.1136/gut.44.4.534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bachem M.G., Schunemann M., Ramadani M., Siech M., Beger H., Buck A., Zhou S., Schmid-Kotsas A., Adler G. Pancreatic carcinoma cells induce fibrosis by stimulating proliferation and matrix synthesis of stellate cells. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:907–921. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.12.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu Z., Pothula S.P., Wilson J.S., Apte M.V. Pancreatic cancer and its stroma: a conspiracy theory. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:11216–11229. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i32.11216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haber P.S., Keogh G.W., Apte M.V., Moran C.S., Stewart N.L., Crawford D.H., Pirola R.C., McCaughan G.W., Ramm G.A., Wilson J.S. Activation of pancreatic stellate cells in human and experimental pancreatic fibrosis. Am J Pathol. 1999;155:1087–1095. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65211-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Apte M.V., Park S., Phillips P.A., Santucci N., Goldstein D., Kumar R.K., Ramm G.A., Buchler M., Friess H., McCarroll J.A., Keogh G., Merrett N., Pirola R., Wilson J.S. Desmoplastic reaction in pancreatic cancer: role of pancreatic stellate cells. Pancreas. 2004;29:179–187. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200410000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ene-Obong A., Clear A.J., Watt J., Wang J., Fatah R., Riches J.C., Marshall J.F., Chin-Aleong J., Chelala C., Gribben J.G., Ramsay A.G., Kocher H.M. Activated pancreatic stellate cells sequester CD8+ T cells to reduce their infiltration of the juxtatumoral compartment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1121–1132. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vonlaufen A., Joshi S., Qu C., Phillips P.A., Xu Z., Parker N.R., Toi C.S., Pirola R.C., Wilson J.S., Goldstein D., Apte M.V. Pancreatic stellate cells: partners in crime with pancreatic cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2085–2093. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erkan M., Kleeff J., Gorbachevski A., Reiser C., Mitkus T., Esposito I., Giese T., Buchler M.W., Giese N.A., Friess H. Periostin creates a tumor-supportive microenvironment in the pancreas by sustaining fibrogenic stellate cell activity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:1447–1464. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yoshida S., Ujiki M., Ding X.Z., Pelham C., Talamonti M.S., Bell R.H., Jr., Denham W., Adrian T.E. Pancreatic stellate cells (PSCs) express cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and pancreatic cancer stimulates COX-2 in PSCs. Mol Cancer. 2005;4:27. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-4-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arumugam T., Brandt W., Ramachandran V., Moore T.T., Wang H., May F.E., Westley B.R., Hwang R.F., Logsdon C.D. Trefoil factor 1 stimulates both pancreatic cancer and stellate cells and increases metastasis. Pancreas. 2011;40:815–822. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31821f6927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guppy N.J., El-Bahrawy M.E., Kocher H.M., Fritsch K., Qureshi Y.A., Poulsom R., Jeffery R.E., Wright N.A., Otto W.R., Alison M.R. Trefoil factor family peptides in normal and diseased human pancreas. Pancreas. 2012;41:888–896. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0b013e31823c9ec5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singh A.P., Arora S., Bhardwaj A., Srivastava S.K., Kadakia M.P., Wang B., Grizzle W.E., Owen L.B., Singh S. CXCL12/CXCR4 protein signaling axis induces sonic hedgehog expression in pancreatic cancer cells via extracellular regulated kinase- and Akt kinase-mediated activation of nuclear factor kappaB: implications for bidirectional tumor-stromal interactions. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:39115–39124. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.409581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Watanabe I., Hasebe T., Sasaki S., Konishi M., Inoue K., Nakagohri T., Oda T., Mukai K., Kinoshita T. Advanced pancreatic ductal cancer: fibrotic focus and beta-catenin expression correlate with outcome. Pancreas. 2003;26:326–333. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200305000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Erkan M., Michalski C.W., Rieder S., Reiser-Erkan C., Abiatari I., Kolb A., Giese N.A., Esposito I., Friess H., Kleeff J. The activated stroma index is a novel and independent prognostic marker in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1155–1161. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ino Y., Yamazaki-Itoh R., Shimada K., Iwasaki M., Kosuge T., Kanai Y., Hiraoka N. Immune cell infiltration as an indicator of the immune microenvironment of pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;108:914–923. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bang U.C., Benfield T., Hyldstrup L., Bendtsen F., Beck Jensen J.E. Mortality, cancer, and comorbidities associated with chronic pancreatitis: a Danish nationwide matched-cohort study. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:989–994. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.12.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weber C.K., Adler G. From acinar cell damage to systemic inflammatory response: current concepts in pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2001;1:356–362. doi: 10.1159/000055834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gabitass R.F., Annels N.E., Stocken D.D., Pandha H.A., Middleton G.W. Elevated myeloid-derived suppressor cells in pancreatic, esophageal and gastric cancer are an independent prognostic factor and are associated with significant elevation of the Th2 cytokine interleukin-13. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2011;60:1419–1430. doi: 10.1007/s00262-011-1028-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clark C.E., Hingorani S.R., Mick R., Combs C., Tuveson D.A., Vonderheide R.H. Dynamics of the immune reaction to pancreatic cancer from inception to invasion. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9518–9527. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Karnevi E., Andersson R., Rosendahl A.H. Tumour-educated macrophages display a mixed polarisation and enhance pancreatic cancer cell invasion. Immunol Cell Biol. 2014;92:543–552. doi: 10.1038/icb.2014.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menen R.S., Hassanein M.K., Momiyama M., Suetsugu A., Moossa A.R., Hoffman R.M., Bouvet M. Tumor-educated macrophages promote tumor growth and peritoneal metastasis in an orthotopic nude mouse model of human pancreatic cancer. In Vivo. 2012;26:565–569. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Germano G., Frapolli R., Belgiovine C., Anselmo A., Pesce S., Liguori M., Erba E., Uboldi S., Zucchetti M., Pasqualini F., Nebuloni M., van Rooijen N., Mortarini R., Beltrame L., Marchini S., Fuso Nerini I., Sanfilippo R., Casali P.G., Pilotti S., Galmarini C.M., Anichini A., Mantovani A., D'Incalci M., Allavena P. Role of macrophage targeting in the antitumor activity of trabectedin. Cancer Cell. 2013;23:249–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhu Y., Knolhoff B.L., Meyer M.A., Nywening T.M., West B.L., Luo J., Wang-Gillam A., Goedegebuure S.P., Linehan D.C., DeNardo D.G. CSF1/CSF1R blockade reprograms tumor-infiltrating macrophages and improves response to T-cell checkpoint immunotherapy in pancreatic cancer models. Cancer Res. 2014;74:5057–5069. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-13-3723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhou J., Song S., Li D., He S., Zhang B., Wang Z., Zhu X. Decoy receptor 3 (DcR3) overexpression predicts the prognosis and pN2 in pancreatic head carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:52. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-12-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chang Y.C., Chen T.C., Lee C.T., Yang C.Y., Wang H.W., Wang C.C., Hsieh S.L. Epigenetic control of MHC class II expression in tumor-associated macrophages by decoy receptor 3. Blood. 2008;111:5054–5063. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-130609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsuji S., Hosotani R., Yonehara S., Masui T., Tulachan S.S., Nakajima S., Kobayashi H., Koizumi M., Toyoda E., Ito D., Kami K., Mori T., Fujimoto K., Doi R., Imamura M. Endogenous decoy receptor 3 blocks the growth inhibition signals mediated by Fas ligand in human pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Int J Cancer. 2003;106:17–25. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stromnes I.M., Brockenbrough J.S., Izeradjene K., Carlson M.A., Cuevas C., Simmons R.M., Greenberg P.D., Hingorani S.R. Targeted depletion of an MDSC subset unmasks pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma to adaptive immunity. Gut. 2014;63:1769–1781. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Emmrich J., Weber I., Nausch M., Sparmann G., Koch K., Seyfarth M., Lohr M., Liebe S. Immunohistochemical characterization of the pancreatic cellular infiltrate in normal pancreas, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic carcinoma. Digestion. 1998;59:192–198. doi: 10.1159/000007488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McAllister F., Bailey J.M., Alsina J., Nirschl C.J., Sharma R., Fan H., Rattigan Y., Roeser J.C., Lankapalli R.H., Zhang H., Jaffee E.M., Drake C.G., Housseau F., Maitra A., Kolls J.K., Sears C.L., Pardoll D.M., Leach S.D. Oncogenic Kras activates a hematopoietic-to-epithelial IL-17 signaling axis in preinvasive pancreatic neoplasia. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:621–637. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rincon M., Anguita J., Nakamura T., Fikrig E., Flavell R.A. Interleukin (IL)-6 directs the differentiation of IL-4-producing CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:461–469. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.De Monte L., Reni M., Tassi E., Clavenna D., Papa I., Recalde H., Braga M., Di Carlo V., Doglioni C., Protti M.P. Intratumor T helper type 2 cell infiltrate correlates with cancer-associated fibroblast thymic stromal lymphopoietin production and reduced survival in pancreatic cancer. J Exp Med. 2011;208:469–478. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Balachandran V.P., Luksza M., Zhao J.N., Makarov V., Moral J.A., Remark R. Identification of unique neoantigen qualities in long-term survivors of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2017;551:512–516. doi: 10.1038/nature24462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Grzesiak J.J., Ho J.C., Moossa A.R., Bouvet M. The integrin-extracellular matrix axis in pancreatic cancer. Pancreas. 2007;35:293–301. doi: 10.1097/mpa.0b013e31811f4526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ohlund D., Franklin O., Lundberg E., Lundin C., Sund M. Type IV collagen stimulates pancreatic cancer cell proliferation, migration, and inhibits apoptosis through an autocrine loop. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Thayer S.P., di Magliano M.P., Heiser P.W., Nielsen C.M., Roberts D.J., Lauwers G.Y., Qi Y.P., Gysin S., Fernandez-del Castillo C., Yajnik V., Antoniu B., McMahon M., Warshaw A.L., Hebrok M. Hedgehog is an early and late mediator of pancreatic cancer tumorigenesis. Nature. 2003;425:851–856. doi: 10.1038/nature02009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bailey J.M., Swanson B.J., Hamada T., Eggers J.P., Singh P.K., Caffery T., Ouellette M.M., Hollingsworth M.A. Sonic hedgehog promotes desmoplasia in pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:5995–6004. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yauch R.L., Gould S.E., Scales S.J., Tang T., Tian H., Ahn C.P., Marshall D., Fu L., Januario T., Kallop D., Nannini-Pepe M., Kotkow K., Marsters J.C., Rubin L.L., de Sauvage F.J. A paracrine requirement for hedgehog signalling in cancer. Nature. 2008;455:406–410. doi: 10.1038/nature07275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kayed H., Kleeff J., Osman T., Keleg S., Buchler M.W., Friess H. Hedgehog signaling in the normal and diseased pancreas. Pancreas. 2006;32:119–129. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000202937.55460.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Heretsch P., Tzagkaroulaki L., Giannis A. Cyclopamine and hedgehog signaling: chemistry, biology, medical perspectives. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 2010;49:3418–3427. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Strand M.F., Wilson S.R., Dembinski J.L., Holsworth D.D., Khvat A., Okun I., Petersen D., Krauss S. A novel synthetic smoothened antagonist transiently inhibits pancreatic adenocarcinoma xenografts in a mouse model. PLoS One. 2011;6:e19904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0019904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith S., Hoyt J., Whitebread N., Manna J., Peluso M., Faia K., Campbell V., Tremblay M., Nair S., Grogan M., Castro A., Campbell M., Ferguson J., Arsenault B., Nevejans J., Carter B., Lee J., Dunbar J., McGovern K., Read M., Adams J., Constan A., Loewen G., Sydor J., Palombella V., Soglia J. The pre-clinical absorption, distribution, metabolism and excretion properties of IPI-926, an orally bioavailable antagonist of the hedgehog signal transduction pathway. Xenobiotica. 2013;43:875–885. doi: 10.3109/00498254.2013.780671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Olive K.P., Jacobetz M.A., Davidson C.J., Gopinathan A., McIntyre D., Honess D. Inhibition of Hedgehog signaling enhances delivery of chemotherapy in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Science. 2009;324:1457–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.1171362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ko A.H., LoConte N., Tempero M.A., Walker E.J., Kate Kelley R., Lewis S., Chang W.C., Kantoff E., Vannier M.W., Catenacci D.V., Venook A.P., Kindler H.L. A phase I study of FOLFIRINOX plus IPI-926, a Hedgehog pathway inhibitor, for advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Pancreas. 2016;45:370–375. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Alvarez R., Musteanu M., Garcia-Garcia E., Lopez-Casas P.P., Megias D., Guerra C., Munoz M., Quijano Y., Cubillo A., Rodriguez-Pascual J., Plaza C., de Vicente E., Prados S., Tabernero S., Barbacid M., Lopez-Rios F., Hidalgo M. Stromal disrupting effects of nab-paclitaxel in pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2013;109:926–933. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2013.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Heinemann V., Reni M., Ychou M., Richel D.J., Macarulla T., Ducreux M. Tumour-stroma interactions in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma: rationale and current evidence for new therapeutic strategies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2014;40:118–128. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2013.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Infante J.R., Matsubayashi H., Sato N., Tonascia J., Klein A.P., Riall T.A., Yeo C., Iacobuzio-Donahue C., Goggins M. Peritumoral fibroblast SPARC expression and patient outcome with resectable pancreatic adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:319–325. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.8824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Neesse A., Frese K.K., Chan D.S., Bapiro T.E., Howat W.J., Richards F.M., Ellenrieder V., Jodrell D.I., Tuveson D.A. SPARC independent drug delivery and antitumour effects of nab-paclitaxel in genetically engineered mice. Gut. 2014;63:974–983. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Aikawa T., Gunn J., Spong S.M., Klaus S.J., Korc M. Connective tissue growth factor-specific antibody attenuates tumor growth, metastasis, and angiogenesis in an orthotopic mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:1108–1116. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.di Mola F.F., Friess H., Martignoni M.E., Di Sebastiano P., Zimmermann A., Innocenti P., Graber H., Gold L.I., Korc M., Buchler M.W. Connective tissue growth factor is a regulator for fibrosis in human chronic pancreatitis. Ann Surg. 1999;230:63–71. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199907000-00010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Abreu J.G., Ketpura N.I., Reversade B., De Robertis E.M. Connective-tissue growth factor (CTGF) modulates cell signalling by BMP and TGF-beta. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:599–604. doi: 10.1038/ncb826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Heng E.C., Huang Y., Black S.A., Jr., Trackman P.C. CCN2, connective tissue growth factor, stimulates collagen deposition by gingival fibroblasts via module 3 and alpha6- and beta1 integrins. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:409–420. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ijichi H., Chytil A., Gorska A.E., Aakre M.E., Bierie B., Tada M., Mohri D., Miyabayashi K., Asaoka Y., Maeda S., Ikenoue T., Tateishi K., Wright C.V., Koike K., Omata M., Moses H.L. Inhibiting Cxcr2 disrupts tumor-stromal interactions and improves survival in a mouse model of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4106–4117. doi: 10.1172/JCI42754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Neesse A., Frese K.K., Bapiro T.E., Nakagawa T., Sternlicht M.D., Seeley T.W., Pilarsky C., Jodrell D.I., Spong S.M., Tuveson D.A. CTGF antagonism with mAb FG-3019 enhances chemotherapy response without increasing drug delivery in murine ductal pancreas cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:12325–12330. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1300415110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Whatcott C.J., Diep C.H., Jiang P., Watanabe A., LoBello J., Sima C., Hostetter G., Shepard H.M., Von Hoff D.D., Han H. Desmoplasia in primary tumors and metastatic lesions of pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:3561–3568. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-1051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Toole B.P., Slomiany M.G. Hyaluronan: a constitutive regulator of chemoresistance and malignancy in cancer cells. Semin Cancer Biol. 2008;18:244–250. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2008.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Michl P., Gress T.M. Improving drug delivery to pancreatic cancer: breaching the stromal fortress by targeting hyaluronic acid. Gut. 2012;61:1377–1379. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Provenzano P.P., Cuevas C., Chang A.E., Goel V.K., Von Hoff D.D., Hingorani S.R. Enzymatic targeting of the stroma ablates physical barriers to treatment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2012;21:418–429. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jacobetz M.A., Chan D.S., Neesse A., Bapiro T.E., Cook N., Frese K.K., Feig C., Nakagawa T., Caldwell M.E., Zecchini H.I., Lolkema M.P., Jiang P., Kultti A., Thompson C.B., Maneval D.C., Jodrell D.I., Frost G.I., Shepard H.M., Skepper J.N., Tuveson D.A. Hyaluronan impairs vascular function and drug delivery in a mouse model of pancreatic cancer. Gut. 2013;62:112–120. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Hingorani S.R., Harris W.P., Beck J.T., Berdov B.A., Wagner S.A., Pshevlotsky E.M., Tjulandin S.A., Gladkov O.A., Holcombe R.F., Korn R., Raghunand N., Dychter S., Jiang P., Shepard H.M., Devoe C.E. Phase Ib study of PEGylated recombinant human hyaluronidase and gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:2848–2854. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Marechal R., Bachet J.B., Mackey J.R., Dalban C., Demetter P., Graham K., Couvelard A., Svrcek M., Bardier-Dupas A., Hammel P., Sauvanet A., Louvet C., Paye F., Rougier P., Penna C., Andre T., Dumontet C., Cass C.E., Jordheim L.P., Matera E.L., Closset J., Salmon I., Deviere J., Emile J.F., Van Laethem J.L. Levels of gemcitabine transport and metabolism proteins predict survival times of patients treated with gemcitabine for pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:664–674.e6. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hingorani S.R., Zheng L., Bullock A.J., Seery T.E., Harris W.P., Sigal D.S., Braiteh F., Ritch P.S., Zalupski M.M., Bahary N., Oberstein P.E., Wang-Gillam A., Wu W., Chondros D., Jiang P., Khelifa S., Pu J., Aldrich C., Hendifar A.E. HALO 202: randomized phase II study of PEGPH20 plus Nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine versus Nab-paclitaxel/gemcitabine in patients with untreated, metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:359–366. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.74.9564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ozdemir B.C., Pentcheva-Hoang T., Carstens J.L., Zheng X., Wu C.C., Simpson T.R., Laklai H., Sugimoto H., Kahlert C., Novitskiy S.V., De Jesus-Acosta A., Sharma P., Heidari P., Mahmood U., Chin L., Moses H.L., Weaver V.M., Maitra A., Allison J.P., LeBleu V.S., Kalluri R. Depletion of carcinoma-associated fibroblasts and fibrosis induces immunosuppression and accelerates pancreas cancer with reduced survival. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:719–734. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rhim A.D., Oberstein P.E., Thomas D.H., Mirek E.T., Palermo C.F., Sastra S.A., Dekleva E.N., Saunders T., Becerra C.P., Tattersall I.W., Westphalen C.B., Kitajewski J., Fernandez-Barrena M.G., Fernandez-Zapico M.E., Iacobuzio-Donahue C., Olive K.P., Stanger B.Z. Stromal elements act to restrain, rather than support, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:735–747. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.04.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Froeling F.E., Feig C., Chelala C., Dobson R., Mein C.E., Tuveson D.A., Clevers H., Hart I.R., Kocher H.M. Retinoic acid-induced pancreatic stellate cell quiescence reduces paracrine Wnt-beta-catenin signaling to slow tumor progression. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1486–1497. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.047. 1497.e1–1497.e14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sherman M.H., Yu R.T., Engle D.D., Ding N., Atkins A.R., Tiriac H., Collisson E.A., Connor F., Van Dyke T., Kozlov S., Martin P., Tseng T.W., Dawson D.W., Donahue T.R., Masamune A., Shimosegawa T., Apte M.V., Wilson J.S., Ng B., Lau S.L., Gunton J.E., Wahl G.M., Hunter T., Drebin J.A., O'Dwyer P.J., Liddle C., Tuveson D.A., Downes M., Evans R.M. Vitamin D receptor-mediated stromal reprogramming suppresses pancreatitis and enhances pancreatic cancer therapy. Cell. 2014;159:80–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Kozono S., Ohuchida K., Eguchi D., Ikenaga N., Fujiwara K., Cui L., Mizumoto K., Tanaka M. Pirfenidone inhibits pancreatic cancer desmoplasia by regulating stellate cells. Cancer Res. 2013;73:2345–2356. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Ji T., Li S., Zhang Y., Lang J., Ding Y., Zhao X., Zhao R., Li Y., Shi J., Hao J., Zhao Y., Nie G. An MMP-2 responsive liposome integrating antifibrosis and chemotherapeutic drugs for enhanced drug perfusion and efficacy in pancreatic cancer. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2016;8:3438–3445. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b11619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Suklabaidya S., Das B., Ali S.A., Jain S., Swaminathan S., Mohanty A.K., Panda S.K., Dash P., Chakraborty S., Batra S.K., Senapati S. Characterization and use of HapT1-derived homologous tumors as a preclinical model to evaluate therapeutic efficacy of drugs against pancreatic tumor desmoplasia. Oncotarget. 2016;7:41825–41842. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.9729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Hama K., Ohnishi H., Aoki H., Kita H., Yamamoto H., Osawa H., Sato K., Tamada K., Mashima H., Yasuda H., Sugano K. Angiotensin II promotes the proliferation of activated pancreatic stellate cells by Smad7 induction through a protein kinase C pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006;340:742–750. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.12.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Hama K., Ohnishi H., Yasuda H., Ueda N., Mashima H., Satoh Y., Hanatsuka K., Kita H., Ohashi A., Tamada K., Sugano K. Angiotensin II stimulates DNA synthesis of rat pancreatic stellate cells by activating ERK through EGF receptor transactivation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;315:905–911. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Masamune A., Hamada S., Kikuta K., Takikawa T., Miura S., Nakano E., Shimosegawa T. The angiotensin II type I receptor blocker olmesartan inhibits the growth of pancreatic cancer by targeting stellate cell activities in mice. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2013;48:602–609. doi: 10.3109/00365521.2013.777776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Chauhan V.P., Martin J.D., Liu H., Lacorre D.A., Jain S.R., Kozin S.V., Stylianopoulos T., Mousa A.S., Han X., Adstamongkonkul P., Popovic Z., Huang P., Bawendi M.G., Boucher Y., Jain R.K. Angiotensin inhibition enhances drug delivery and potentiates chemotherapy by decompressing tumour blood vessels. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2516. doi: 10.1038/ncomms3516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Doi C., Egashira N., Kawabata A., Maurya D.K., Ohta N., Uppalapati D., Ayuzawa R., Pickel L., Isayama Y., Troyer D., Takekoshi S., Tamura M. Angiotensin II type 2 receptor signaling significantly attenuates growth of murine pancreatic carcinoma grafts in syngeneic mice. BMC Cancer. 2010;10:67. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-10-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Erkan M., Reiser-Erkan C., Michalski C.W., Deucker S., Sauliunaite D., Streit S., Esposito I., Friess H., Kleeff J. Cancer-stellate cell interactions perpetuate the hypoxia-fibrosis cycle in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Neoplasia. 2009;11:497–508. doi: 10.1593/neo.81618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Bailey K.M., Cornnell H.H., Ibrahim-Hashim A., Wojtkowiak J.W., Hart C.P., Zhang X., Leos R., Martinez G.V., Baker A.F., Gillies R.J. Evaluation of the “steal” phenomenon on the efficacy of hypoxia activated prodrug TH-302 in pancreatic cancer. PLoS One. 2014;9:e113586. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Borad M.J., Reddy S.G., Bahary N., Uronis H.E., Sigal D., Cohn A.L., Schelman W.R., Stephenson J., Jr., Chiorean E.G., Rosen P.J., Ulrich B., Dragovich T., Del Prete S.A., Rarick M., Eng C., Kroll S., Ryan D.P. Randomized phase II trial of gemcitabine plus TH-302 versus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:1475–1481. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.55.7504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Kindler H.L., Niedzwiecki D., Hollis D., Sutherland S., Schrag D., Hurwitz H., Innocenti F., Mulcahy M.F., O'Reilly E., Wozniak T.F., Picus J., Bhargava P., Mayer R.J., Schilsky R.L., Goldberg R.M. Gemcitabine plus bevacizumab compared with gemcitabine plus placebo in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: phase III trial of the Cancer and Leukemia Group B (CALGB 80303) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3617–3622. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Pothula S.P., Xu Z., Goldstein D., Biankin A.V., Pirola R.C., Wilson J.S., Apte M.V. Hepatocyte growth factor inhibition: a novel therapeutic approach in pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;114:269–280. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Brandes F., Schmidt K., Wagner C., Redekopf J., Schlitt H.J., Geissler E.K., Lang S.A. Targeting cMET with INC280 impairs tumour growth and improves efficacy of gemcitabine in a pancreatic cancer model. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:71. doi: 10.1186/s12885-015-1064-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jiang H., Hegde S., Knolhoff B.L., Zhu Y., Herndon J.M., Meyer M.A., Nywening T.M., Hawkins W.G., Shapiro I.M., Weaver D.T., Pachter J.A., Wang-Gillam A., DeNardo D.G. Targeting focal adhesion kinase renders pancreatic cancers responsive to checkpoint immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2016;22:851–860. doi: 10.1038/nm.4123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Morris J.P., 4th, Wang S.C., Hebrok M. KRAS, Hedgehog, Wnt and the twisted developmental biology of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:683–695. doi: 10.1038/nrc2899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.White B.D., Chien A.J., Dawson D.W. Dysregulation of Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in gastrointestinal cancers. Gastroenterology. 2012;142:219–232. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Zhang Y., Morris J.P., 4th, Yan W., Schofield H.K., Gurney A., Simeone D.M., Millar S.E., Hoey T., Hebrok M., Pasca di Magliano M. Canonical wnt signaling is required for pancreatic carcinogenesis. Cancer Res. 2013;73:4909–4922. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Pasca di Magliano M., Biankin A.V., Heiser P.W., Cano D.A., Gutierrez P.J., Deramaudt T., Segara D., Dawson A.C., Kench J.G., Henshall S.M., Sutherland R.L., Dlugosz A., Rustgi A.K., Hebrok M. Common activation of canonical Wnt signaling in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. PLoS One. 2007;2:e1155. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Wang L., Heidt D.G., Lee C.J., Yang H., Logsdon C.D., Zhang L., Fearon E.R., Ljungman M., Simeone D.M. Oncogenic function of ATDC in pancreatic cancer through Wnt pathway activation and beta-catenin stabilization. Cancer Cell. 2009;15:207–219. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.01.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Zeng G., Germinaro M., Micsenyi A., Monga N.K., Bell A., Sood A., Malhotra V., Sood N., Midda V., Monga D.K., Kokkinakis D.M., Monga S.P. Aberrant Wnt/beta-catenin signaling in pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Neoplasia. 2006;8:279–289. doi: 10.1593/neo.05607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Emami K.H., Nguyen C., Ma H., Kim D.H., Jeong K.W., Eguchi M., Moon R.T., Teo J.L., Kim H.Y., Moon S.H., Ha J.R., Kahn M. A small molecule inhibitor of beta-catenin/CREB-binding protein transcription. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:12682–12687. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0404875101. [corrected] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]