Abstract

Pulmonary invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (IMA) is considered a variant of lung adenocarcinomas based on the current World Health Organization classification of lung tumors. However, the molecular mechanism driving IMA development and progression is not well understood. Thus, we surveyed the genomic characteristics of IMA in association with immune-checkpoint expression to investigate new potential therapeutic strategies. Tumor cells were collected from surgical specimens of primary IMA, and sequenced to survey 53 genes associated with lung cancer. The mutational profiles thus obtained were compared in silico to conventional adenocarcinomas and other histologic carcinomas, thereby establishing the genomic clustering of lung cancers. Immunostaining was also performed to compare expression of programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) and B7-H3 in IMA and conventional adenocarcinomas. Mutations in Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS) were detected in 75% of IMAs, but in only 11.6% of conventional adenocarcinomas. On the other hand, the frequency of mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and tumor protein p53 (TP53) genes was 5% and 10%, respectively, in the former, but 48.8% and 34.9%, respectively, in the latter. Clustering of all 78 lung cancers indicated that IMA is distinct from conventional adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma. Strikingly, expression of PD-L1 in ≥1% of cells was observed in only 6.1% of IMAs, but in 59.7% of conventional adenocarcinomas. Finally, 42.4% and 19.4% of IMAs and conventional adenocarcinomas, respectively, tested positive for B7-H3. Although currently classified as a variant of lung adenocarcinoma, it is also reasonable to consider IMA as fundamentally distinct, based on mutation profiles and genetic clustering as well as immune-checkpoint status. The immunohistochemistry data suggest that B7-H3 may be a new and promising therapeutic target for immune checkpoint therapy.

Keywords: lung cancer, invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma, next-generation sequencing, clustering, immunocheckpoint

1. Introduction

Invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (IMA), which represents 2–10% of all lung adenocarcinomas, is considered one of the most malignant subtypes and is associated with poor prognosis [1,2,3]. IMA presents a unique histology among primary lung cancers, and is typified by columnar or goblet cells with basally located nuclei and pale cytoplasm containing varying amounts of mucin [4]. Accordingly, the clinical presentation of IMA is distinct from that of conventional nonmucinous adenocarcinoma [5,6,7]. For example, IMA patients frequently present pneumonia-like symptoms with multifocal and multilobar lesions [5]. Although standard chemotherapy is the only treatment option at advanced stages, no targeted therapy has been demonstrated to be effective against IMA.

IMAs are strongly correlated with mutations in Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS), which are present in 28–87% of cases [4,5,6,7,8]. However, the correlation between the genetic characteristics and immune-checkpoint expression is unclear and no specific immune checkpoint therapy is established for IMA, although such therapy has recently attracted attention as treatment for non-small cell lung cancer. Molecular studies have been limited and therapeutic targets remain yet to be identified partly because IMA is relatively rare compared to other subtypes. In this study, we surveyed gene mutations in IMA by targeted next-generation sequencing, and propose a novel classification of lung cancers based on clustering of mutational profiles. Furthermore, we investigated by immunohistochemistry the potential of immune checkpoint blockade as therapy against IMA.

2. Results

2.1. Patient Characteristics

At first, we enrolled 20 IMA patients and 43 patients with nonmucinous adenocarcinoma (NMA) who underwent surgery at our hospital (Supplementary Table S1). IMA and NMA patients were comparable in age, sex, lung function, smoking habit, tumor location, surgical procedure received, tumor size, pathological stage, and lymphatic or vessel invasion (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1). However, computed tomography revealed that part-solid tumors with ground-glass nodules were more frequent in IMA patients than in NMA patients, and there were no cases of IMA with ground-glass nodules only (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | IMA (n = 20) | NMA (n = 43) | p Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 72.7 ± 7.9 | 67.9 ± 8.3 | 0.98 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 12 (60%) | 27 (62.8%) | 0.83 |

| Female | 8 (40%) | 16 (37.2%) | |

| Performance Status | |||

| 0 | 17 (85%) | 36 (83.7%) | |

| 1 | 3 (15%) | 7 (16.3%) | 0.90 |

| ≧2 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Smoking habit | |||

| Never | 10 (50%) | 15 (34.9%) | 0.26 |

| Former/current | 10 (50%) | 28 (65.1%) | |

| Smoking index | 383 ± 107 | 476 ± 86 | 0.26 |

| CT finding | |||

| Solid | 9 (45%) | 20 (46.5%) | |

| Part solid GGN | 11 (55%) | 8 (18.6%) | 0.0002 |

| GGN | 0 (0%) | 15 (34.9%) | |

| Tumor location | |||

| Central | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | |

| Middle | 7 (35%) | 8 (18.6%) | 0.16 |

| Peripheral | 13 (65%) | 35 (81.4%) | |

| Surgical procedure received | |||

| Sublobar resection | 1 (5%) | 10 (23.3%) | |

| Lobectomy | 18 (90%) | 30 (69.8%) | 0.15 |

| Pneumonectomy | 1 (5%) | 1 (2.3%) | |

| Other | 0 (0%) | 2 (4.6%) | |

| Tumor size (mm) | 37.2 ± 6.8 | 20.7 ± 1.4 | 1.00 |

| Pathological stage | |||

| I | 17 (85%) | 38 (88.4%) | |

| II | 3 (15%) | 1 (2.3%) | 0.10 |

| III | 0 (0%) | 3 (7.0%) | |

| IV | 0 (0%) | 1 (2.3%) | |

| Pathological lymphatic invasion | |||

| Absent | 18 (90%) | 37 (86.5%) | 0.66 |

| Present | 2 (10%) | 6 (13.5%) | |

| Pathological vessel invasion | |||

| Absent | 17 (85%) | 33 (76.7%) | |

| Microscopically present | 3 (15%) | 10 (23.3%) | 0.44 |

| Macroscopically present | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

IMA, invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma; NMA, nonmucinous adenocarcinoma; CT, computed tomography; GGN, ground-glass nodule. Peripheral, central, and middle lung cancers correspond to primary lesions located in the outer, inner, or middle one-third of the lung field, respectively. Pathological staging was performed according to the International Union Against Cancer tumor–node–metastasis classification (eighth edition).

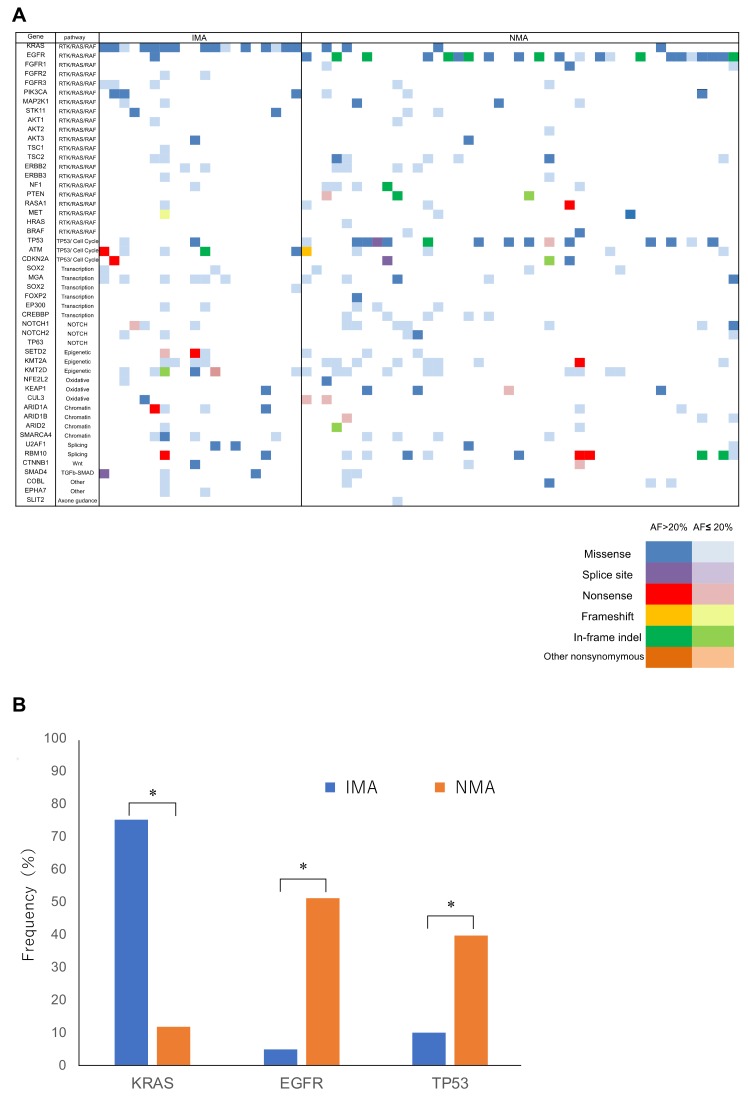

2.2. Panel Sequencing

Significant mutations, i.e., those with allele fraction ≥1%, are shown in Figure 1A and listed in Supplementary Table S2 for 20 IMAs and 43 NMAs. Remarkably, KRAS mutations were detected in 75% of IMAs (15/20), but only in 11.6% of NMAs (5/43), a statistically significant difference in frequency (Figure 1B). The frequency of mutations in epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) and tumor protein p53 (TP53) were 5% (1/20) and 10% (2/20), respectively, in IMA patients, which are significantly lower rates than the corresponding frequencies of 48.8% (21/43) and 34.9% (15/43) in patients with conventional lung adenocarcinoma (p < 0.05, Figure 1B). We note that no significant differences were observed in the mutation burden when the cutoff value was set at allele fraction less than 1% (p = 0.82). There were also no significant differences in the distribution of pathways affected in IMAs and NMAs (Supplementary Table S3).

Figure 1.

Mutational profile of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (IMA) and nonmucinous adenocarcinoma (NMA). (A) Most specimens harbored multiple mutations affecting several different functional pathways. However, the prevalence of Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (KRAS), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and tumor protein p53 (TP53) mutations was different between IMA and NMA. Nonsynonymous mutations are color-coded as indicated, with dark colors representing allele fractions >20%, and light colors representing allele fractions ≤20%. (B) KRAS mutations were significantly more frequent in IMA than in NMA. In contrast, mutations in EGFR and TP53 were significantly less frequent in IMA than in NMA. *, p < 0.05.

2.3. In Silico Analysis

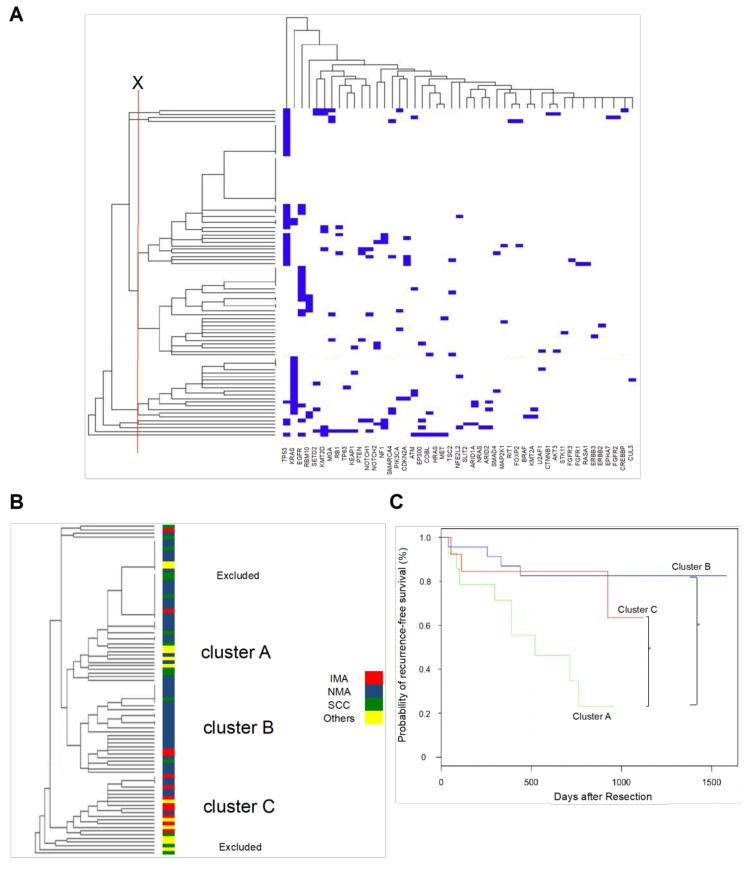

Mutations obtained by targeted sequencing of specimens from patients with IMA (n = 12), NMA (n = 43), squamous cell carcinoma (n = 13), and other tumors (n = 10) were clustered based on similarity by in silico unsupervised hierarchical clustering (Figure 2A). Twelve representative IMA cases were selected out of 20 IMA cases for the hierarchical clustering analysis and the other histological cancers, including squamous cell carcinoma, small cell carcinoma and sarcomatoid cancer, were additionally enrolled as an external control, in order that the inclusion criteria of this analysis might reflect, to some extent, the incidence rate in general of each histological cancer in surgically treated cases (Supplementary Table S1). Results of this analysis were visualized in a dendrogram, in which patients are connected by bars of length proportional to the genetic similarity between them. Upon exclusion of specimens with very few (0–1) mutations detected, as well as a few genetically very remote tumors, most patients were classified into Clusters A, B, and C (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Hierarchical clustering of lung cancer. (A) Full view of the cluster diagram. Unsupervised hierarchical clustering was used to group correlated mutations into several clusters, which were assigned based on the threshold marked in red. Results were visualized in TreeView, with mutations on the horizontal axis and cases on the vertical axis. Cases and mutations are arranged such that the most similar are placed next to each other. The length of branches connecting cases or mutations is inversely proportional to profile similarity. (B) In this representation, clusters are shown by color-coded dendrogram branches, and conventional histological classifications are superimposed using color-coded bars. Clusters A, B, and C are predominantly squamous cell carcinoma, NMA, and IMA, respectively. (C) Recurrence-free survival in individual genomic clusters. Postoperative recurrence-free survival was significantly lower in Cluster A than in Clusters B and C. *, p < 0.05.

No significant differences among clusters were observed in age or pathological stage (Table 2), although Cluster A contained significantly more men (p = 0.003) and heavy smokers (p = 0.008). Importantly, histologic subtypes were unevenly distributed among clusters (Table 2, p = 0.001), with 66.7% of squamous cell carcinoma patients grouped in Cluster A, and 80% of IMA cases grouped in Cluster C (Table 2, Figure 2B). In Cluster B, 87.0% of specimens were conventional adenocarcinoma (Table 2, Figure 2B). Patients with other histologic subtypes, including small cell carcinoma and pleomorphic carcinoma, were distributed among Clusters A and C (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of genomic clusters.

| Characteristic | Cluster A | Cluster B | Cluster C | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 14 | n = 23 | n = 15 | |||

| Sex | 0.003 | ||||

| male | 14 (100%) | 13 (56.5%) | 9 (60%) | ||

| female | 0 (0%) | 10 (43.5%) | 6 (40%) | ||

| Age | 70.4 ± 8.7 | 70.2 ± 7.9 | 70.6 ± 8.0 | 0.952 | |

| Smoking index | 0.008 | ||||

| 0 | 0 | 10 | 5 | ||

| 1–1000 | 7 | 10 | 6 | ||

| 1000< | 7 | 3 | 4 | ||

| Histology | 0.001 | ||||

| NMA | 6 | 20 | 4 | ||

| IMA | 0 | 2 | 8 | ||

| SCC | 4 | 1 | 1 | ||

| other | 4 | 0 | 2 | ||

| Pathological stage | 0.158 | ||||

| 0-IA | 4 | 15 | 8 | ||

| IB | 4 | 6 | 3 | ||

| IIA-IV | 6 | 2 | 4 | ||

IMA, invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma; NMA, nonmucinous adenocarcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma.

2.4. Correlation between Cluster Classification and Outcome

Postoperative recurrence-free survival was significantly poorer in Cluster A than in Clusters B and C (Figure 2C, log-rank p < 0.05, Supplementary Table S1). Based on Cox’s proportional hazards model, pathological stage and cluster are independent risk factors for postoperative recurrence or mortality, whereas sex, age, smoking habit, and histology are not (Table 3).

Table 3.

Multivariate proportional hazard model of risk factors for postoperative recurrence or mortality.

| Variables | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | p Value |

|---|---|---|

| Cluster | ||

| cluster A | 1 (Ref.) | |

| cluster B | 0.25 (0.05–0.94) | 0.04 |

| cluster C | 0.18 (0.03–0.78) | 0.02 |

| Pathological stage | ||

| stage 0 or IA | 1 (Ref.) | |

| stage IB | 22.58 (1.80–881.50) | 0.01 |

| stage IIA or more | 36.09 (2.83–1972.69) | 0.003 |

| Male (ref. Female) | 1.25 (0.24–9.21) | 0.75 |

| Age | ||

| –65 | 1 (Ref.) | |

| 66–75 | 1.08 (0.34–7.36) | 0.71 |

| 76– | 1.22 (0.56–8.31) | 0.55 |

| Smoker (ref. non-smoker) | 1.56 (0.61–8.54) | 0.74 |

| Histology | ||

| NMA | 1 (Ref.) | |

| IMA | 0.46 (0.01–7.14) | 0.60 |

| SCC | 6.94 (0.34–163.65) | 0.20 |

| Others | 3.05 (0.05–295.07) | 0.59 |

NMA, nonmucinous adenocarcinoma; IMA, invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma; SCC, squamous cell carcinoma; Ref., reference.

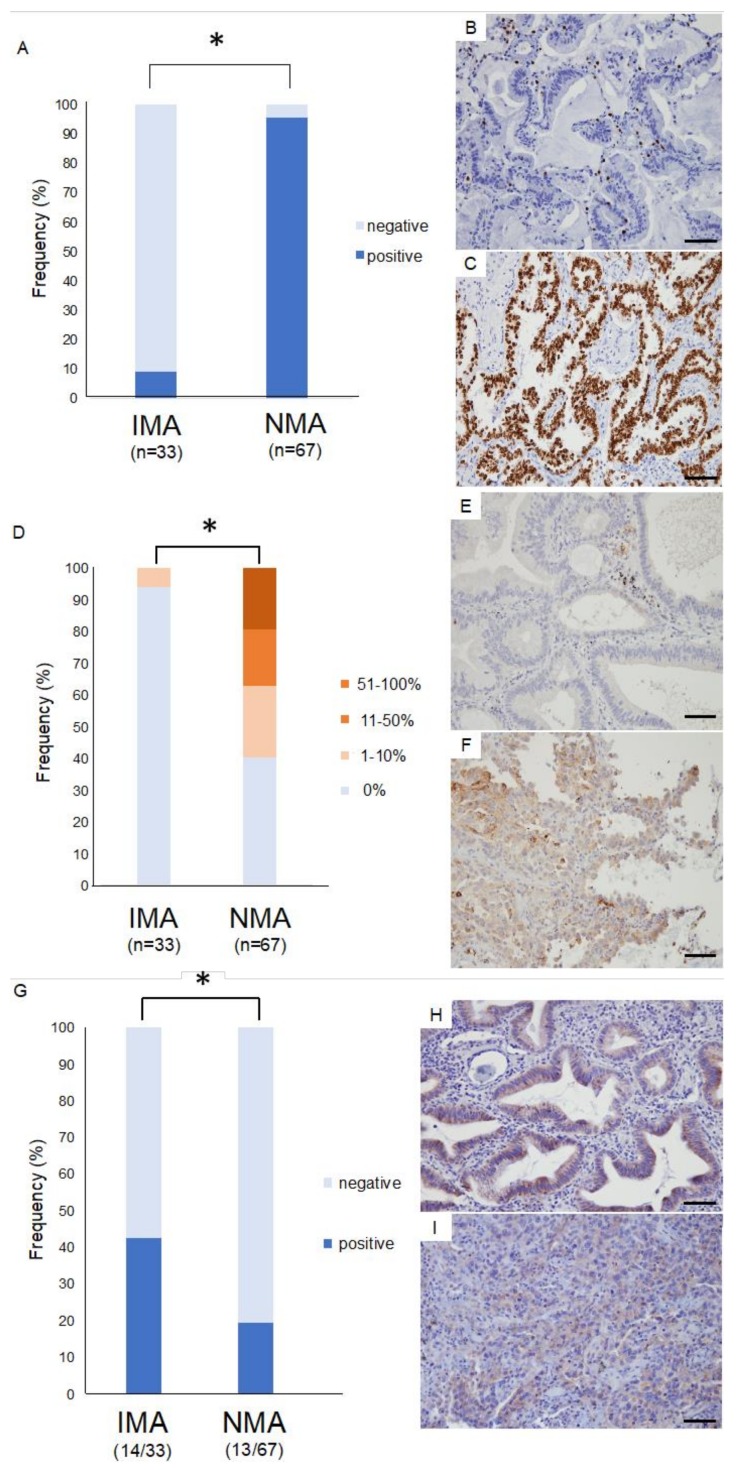

2.5. Immunohistology for Thyroid Transcription Factor 1 (TTF-1)

For immunohistochemistry study, 13 IMAs and 24 NMAs were additionally enrolled and 33 IMAs and 67 NMAs were examined and compared in total.

TTF-1 was detected in only three of 33 IMA specimens (9.1%). This proportion was significantly lower than in NMA specimens, of which 41 of 43 (95.5%) tested positive for TTF-1 (Figure 3A–C, p < 0.001).

Figure 3.

Immunostaining for thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1) and immune checkpoint proteins in invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma (IMA) and nonmucinous adenocarcinoma (NMA). (A) TTF-1 was detected in nearly all patients with NMA, but in only a few patients with IMA. *, p < 0.05. (B,C) Representative TTF-1 immunostaining in IMA (B) and NMA (C). (D) Programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1) was detected in 59.7% patients with nonmucinous adenocarcinoma, but in only 6.1% of patients with invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma, a statistically significant difference in frequency. *, p < 0.05. (E,F) Representative PD-L1 immunostaining in IMA (E) and NMA (F). (G) B7-H3 was detected in 19.4% patients with NMA and in 42.4% of patients with IMA, a statistically significant difference in frequency. *, p < 0.05. (H,I) Representative B7-H3 immunostaining in IMA (H) and NMA (I). Scale bars: 100 μm.

2.6. Immunohistology for Immunocheckpoint Proteins

Immunocheckpoint proteins such as programmed death ligand 1 (PD-L1: B7-H1), V-set domain-containing T-cell activation inhibitor 1 (VTCN1: B7-H4), and B7-H3 were also assayed in formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded specimens. The molecules PD-L1, B7-H3, and VTCN1 belong to a family of immune modulators and have garnered attention as a promising molecular target for immunocheckpoint therapy. PD-L1 was assessed according to a four-tier scale, corresponding to specimens in which the plasma membrane is positively stained in 0%, 1–10%, 11–50%, and 51–100% of cells. Remarkably, only two of 33 IMA specimens (6.1%) tested positive for PD-L1, a positive test being defined as staining of ≥1% of cells. In contrast, a significantly larger number of NMA specimens tested positive (40/67 patients, 59.7%) (Figure 3D–F, p < 0.05). VTCN1 was detected in 3 of 13 patients with squamous cell carcinoma (22%), but not in any other patients (Supplementary Figure S1). Finally, B7-H3 was detected in 14 of 33 IMA patients (42.4%). This proportion was significantly higher than in NMA specimens, of which 13 of 67 (19.4%) tested positive for B7-H3 (Figure 3G–I, p < 0.05). In addition, signal intensity tends to be stronger in IMA than in NMA (Figure 3H,I).

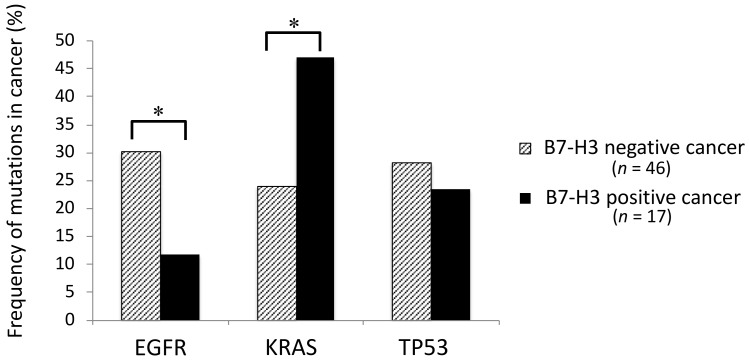

2.7. Association between the Mutation Profiles and Immunocheckpoint Molecules

Based on the aforementioned results, the association between the mutation profiles and immunocheckpoint molecules was examined. Estimates of tumor mutation burden by targeted sequencing did not correlate with PD-L1 or B7-H3 expression (Figure 4A,C, p = 0.79, 0.86, respectively). No significant differences of PD-L1 expression were detected among the mutational clusters A, B and C (Figure 4B, p = 0.81). Thus, tumor mutation profiles and PD-L1 expression were basically found to be independent variables. On the other hand, B7-H3 expression was significantly elevated in the cluster C compared with the clusters A and B (Figure 4D, p < 0.05).

Figure 4.

Association between the mutation profiles and PD-L1 expression. (A) Estimates of tumor mutation burden and PD-L1 expression. The number of mutations detected by targeted sequencing was not significantly different among the cancers with different PD-L1 expressions (p = 0.79). (B) Comparison of PD-L1 expression among the genomic clusters of cancer. PD-L1 expression was not significantly different among the clusters A, B and C (p = 0.81). (C) Estimates of tumor mutation burden and B7-H3 expression. The number of mutations detected by targeted sequencing was not significantly different between the cancers with and without B7-H3 expressions (p = 0.86). (D) Comparison of B7-H3 expression among the genomic clusters of cancer. B7-H3 expression was significantly elevated in the cluster C compared with the clusters A and B. *, p < 0.05.

EGFR mutations were affected significantly more frequently in B7-H3 negative adenocarcinomas than in B7-H3 positive adenocarcinomas, while KRAS mutations were affected significantly more frequently in B7-H3 positive adenocarcinomas than in B7-H3 negative adenocarcinomas (Figure 5, *, p < 0.05). No significant difference of frequency was found in TP53 mutations between B7-H3 positive and negative adenocarcinomas (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Frequency of EGFR, KRAS, and TP53 mutations with or without B7-H3 positivity in adenocarcinoma. There are significant differences of frequency in EGFR and KRAS mutations between B7-H3 positive and negative adenocarcinomas. *, p < 0.05.

3. Discussion

In this study, we found that lung IMA is genetically distinct from other lung cancers. KRAS mutations were the most frequent drivers, while EGFR mutations were rare, in line with previous studies [4,5,6,7,8]. TP53 mutations were similarly rare in IMA, and were detected in only 2 of 20 IMA cases examined, but in approximately 35% of NMA cases. Thus, the mutational profile of IMA is distinct from that of NMA. Accordingly, genomic clustering segregated IMA apart from squamous cell carcinoma and conventional adenocarcinoma. In addition, immunohistology for major immunocheckpoint molecules suggested that, although blockade of programmed death 1 (PD-1) and PD-L1 is unlikely to be effective against IMA, blockade of B7-H3 may prove successful.

Based on the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer (IASLC)/the American Thoracic Society (ATS)/the European Respiratory Society (ERS) classification, lung adenocarcinomas are either nonmucinous (nonmucinous adenocarcinoma in situ, nonmucinous minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, and NMA) or mucinous (mucinous adenocarcinoma in situ, mucinous minimally invasive adenocarcinoma, IMA, and colloid-predominant adenocarcinoma) [1]. In a survey of 864 surgical cases, Kadota et al. found that 42 (5%) were mucinous, including 1 case of mucinous minimally invasive adenocarcinoma (0.1%), 36 cases of IMA (4%), and 5 cases of colloid-predominant tumors (0.6%) [7]. No mucinous adenocarcinoma in situ was observed [7]. Similarly, mucinous adenocarcinoma in situ was not present in our cohort, which may explain why pure ground-glass opacity was not observed radiologically (Table 1).

In silico analysis suggests some correlation between genomic characteristics and the World Health Organization lung cancer classification. For instance, Cluster A was predominantly composed of squamous cell carcinomas, Cluster B consisted mostly of NMAs, and Cluster C consisted mostly of IMAs. This result suggests that IMA is genetically distinct, although histologic–molecular associations are typically not 100% specific. Nevertheless, cluster classes were significantly associated with postoperative recurrence-free survival, while histologic subtype was not. Thus, hierarchical clustering based on gene mutations is novel, meaningful, and functional classification of lung tumors. Taken together, these findings may explain why IMA is refractory to conventional chemotherapies, and may require different therapeutic strategies.

Although IMA outcomes following surgical resection are relatively favorable, therapeutic outcomes from advanced IMA are extremely poor [2,3]. Thus, a more suitable therapy is currently under development. As IMA tumors lack the major driver mutations present in lung adenocarcinoma, including in TP53 and EGFR, one might expect IMA tumors to respond instead to agents that target KRAS mutations. However, KRAS itself has proven difficult to inhibit, and the effectiveness of agents that target key KRAS effectors is diminished by compensatory or parallel pathways [9,10]. Thus, combinations of the blockade agents are more promising. For example, Manchado et al. recently reported that a combination of MEK and FGFR inhibitors is effective against lung cancers with KRAS mutations [11]. Similarly, Kitai et al. reported that combinations of MEK and FGFR inhibitors, may be effective against mesenchymal-like KRAS-mutated non-small cell lung carcinoma [12].

Expression of TTF-1, also known as NK2 homeobox-1 (NKX2-1) target protein, is restricted to the lung and thyroid. Accordingly, TTF-1 is frequently used as a marker to distinguish carcinomas of pulmonary and thyroid origin [13]. Of note, loss of TTF-1 and altered differentiation states are associated with IMA, implying that IMA and NMA arise from different cellular lineages [14]. In addition, several studies observed frequent NKX2-1 mutations in IMA, and proposed NKX2-1 as a lineage-specific tumor suppressor in the lung [15,16]. Similarly, mice with KRAS mutations and NKX2-1 deletion develop lung tumors that resemble human mucinous lung adenocarcinomas [17,18]. In addition, Guo et al. showed that restoration of TTF-1 expression in mucinous lung cancer cells induces expression of PD-L1 in vitro, suggesting that loss of PD-L1 in IMA may be due to loss of TTF-1 [19]. Collectively, these observations suggest that a specific genomic profile may drive the phenotypic characteristics of IMA, and provide possible routes to therapy.

Immune checkpoints are a suite of costimulatory and inhibitory molecules in T cells that control the amplitude and quality of the immune response [20]. To evade immunity, tumors may overexpress or activate inhibitory immune checkpoints, especially PD-1 and its ligand PD-L1 [21]. While antibodies that inhibit the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway produce a durable clinical response in various solid tumors including non-small cell lung cancer [22,23], they only benefit a fraction of patients. Indeed, our data now suggest that such antibodies are likely to be ineffective against IMA. B7-H3 and B7-H4 (VTCN1) belong to a family of immune modulators that includes PD-L1 (B7-H1) and are regarded as a promising molecular target for immunocheckpoint therapy [24]. In fact, many preclinical studies reported the possible effectiveness of B7-H3- or B7-H4-targeting antibody, among the B7 family, in the treatment of cancers [25,26,27,28,29]. Furthermore, since we would like to elevate our study to translational research, we focused on B7-H3 and B7-H4, which are currently being tested in a clinical trial [30,31,32]. Inamura et al. showed B7-H3 was significantly associated with lung adenocarcinoma in smokers and/or patients with wild type EGFR [33]. Our data also showed that B7-H3-positive adenocarcinomas harbor EGFR mutations significantly less frequently, suggesting a non-redundant biological role of the two targets: EGFR and B7-H3. It was also revealed that B7-H3-expressing cancers harbor KRAS mutations significantly more frequently, which may make a breakthrough in the treatment of KRAS mutant lung cancers. Moreover, KRAS positivity and EGFR negativity is a typical genomic pattern of IMA. Notably, approximately 40% of IMA tumors in our study express B7-H3, whereas none of them strongly express PD-L1, indicating that the former is a better immunotherapeutic target in IMA patients than the latter. This finding may open new avenues of treatment based on immune checkpoint inhibitors against proteins other than PD-1/PD-L1.

Proctor et al. reported that B7-H3 expression was elevated in meningiomas harboring gene mutations affecting the AKT pathway [34]. In the case of lung cancer, it is well known that EGFR or KRAS affects the AKT pathway, whereas wild-type EGFR was reported to be associated with B7-H3 expression [33]. i.e., KRAS mutation may be the key trigger of B7-H3 expression in lung cancer. In fact, the cases in cluster C, which are mainly related to KRAS mutations, expressed B7-H3 most frequently. Importantly, genomic clustering in this study was directly associated with B7-H3 expression, and, thus, distinguished the cancers which can be treated by the B7-H3 blockade therapy.

In our paper, we focused on the relation between the genomic profiles and phenotypic characteristics of IMA. To summarize our data and previous reports, IMA usually harbors both KRAS and NKX2-1 mutations, both of which are oncogenic [19]. It is estimated that NKX2-1 mutation leads to loss of TTF-1 and PD-L1 expressions, while KRAS mutation tends to upregulate B7-H3 expression—presumably by disrupting the AKT pathway [19,34]. Eventually, B7-H3 can be considered as a new therapeutic target, well specific to IMA.

B7-H3 is a type I transmembrane protein and B7 immunoregulatory molecule of the Ig superfamily [35]. While B7-H3 mRNA is broadly expressed in the human breast, bladder, liver, lung, lymphoid organs, placenta, prostate, and testis [36,37,38], protein expression is low and rare [39]. However, B7-H3 is upregulated in several malignancies including non-small cell lung cancer [40]. In preclinical models, both stimulatory and inhibitory activities have been postulated for B7-H3 in T cell activity against tumors [35,36,37,39]. For example, B7-H3 expression is linked to decreased T cell proliferation and interferon-γ production in human hepatocellular carcinoma [41]. Similarly, B7-H3 blockade increased CD8+ T cell proliferation and activity in mouse models of pancreatic cancer [42].

Enoblituzumab, also known as MGA271, is a humanized, Fc-optimized monoclonal antibody against B7-H3, and was shown to be active against a fraction of heavily pretreated solid tumors and was well-tolerated at typical doses in a Phase 1 study [32]. The antibody is reported to have limited activity against normal tissue, and its Fc domain supposedly enhances antitumor activity [32]. The clinical activity of the antibody for B7-H3-expressing cancers is currently under investigation, alone or in combination with monoclonal antibodies against either CTLA-4 or PD-L1 [32]. We anticipate that MGA271 will demonstrate potent antitumor activity against IMA, which expresses B7-H3 but not PD-L1 and is otherwise difficult to treat, in contrast to NMA.

4. Methods

4.1. Patients and Sample Preparation

The survey covered 123 patients who underwent surgery for lung cancer in our department between June 2014 and June 2018. We obtained written informed consent from these patients for genetic research, in accordance with protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board at our hospital. Specimens were typed histologically according to World Health Organization classification (third edition) [43], and staged according to International Union Against Cancer TNM classification (eighth edition) [44]. In total, 86 cancers were subject to the mutation analysis, which included 20 IMA, 43 conventional adenocarcinomas, 13 squamous cell carcinomas, and 10 other histological cancers. Of these 20 IMA, 16 were pure mucinous, and 4 were mixed mucinous/nonmucinous. Serial sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissue were stained with hematoxylin-eosin and microdissected using an ArcturusXT laser-capture microdissection system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Tokyo, Japan). DNA was extracted by QIAamp DNA FFPE Tissue Kit (Qiagen, Tokyo, Japan), and DNA quality was checked using primers against ribonuclease P. A peripheral blood sample was also drawn from each patient just before surgery. The blood sample was centrifuged, and DNA was extracted from the buffy coat by utilizing QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Qiagen).

4.2. Targeted Deep Sequencing and Data Analysis

A panel of exons in 53 genes (see Supplementary Table S4) was established based on (a) frequent association with lung cancer, as reported in TCGA [45,46] and other surveys [47,48,49,50,51], and (b) frequent mutation in lung cancer, as reported in COSMIC, Catalogue of Somatic Mutations In Cancer [52] Primers for panel sequencing were designed in Ion AmpliSeq (Thermo Fisher Scientific) as we previously reported [53,54,55,56,57,58,59]. Sequencing libraries were made by Ion AmpliSeq Library Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After barcoding with Ion Xpress Barcode Adapters (Thermo Fisher Scientific), libraries were purified using Agencourt AMPure XP (Beckman Coulter, Tokyo, Japan) and quantified by Ion Library Quantitation Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). After being templated with Ion PI Template OT2 200 Kit v3 (Thermo Fisher Scientific), the libraries were sequenced on an Ion Proton (Ion Torrent) using Ion PI Sequencing 200 Kit v3.

Raw signal data were analyzed in Torrent Suite version 4.0, and processed by standard Ion Torrent Suite Software. The pipeline was composed of signal processing, base calling, quality score assignment, read alignment to human genome 19, quality control of mapping, and coverage analysis. Single nucleotide variants, insertions, and deletions were then annotated by tumor–normal pair analysis against lymphocytes from peripheral blood, using Ion Reporter Server System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Results were visualized with Integrative Genomics Viewer (Broad institute, Boston, MA, USA).

4.3. In Silico Clustering

Hierarchical clustering generates a binary tree, in which the most similar patterns are clustered. To organize tumor mutational profiles into meaningful structures based on similarity or dissimilarity, we used unsupervised hierarchical clustering with average and complete linkage algorithms in GeneCluster, applying the same approach as previously reported [60,61,62,63]. This process places cases with similar mutation profiles as neighboring rows in the clustergram. Relationships between cases were then visualized as a dendrogram with branch length inversely proportional to the similarity between mutational profiles. Only mutations with allele fraction more than 1.0% were included in this analysis. Results were visualized with TreeView [64].

4.4. Immunohistochemistry

Formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded tissues were sectioned at 5 μm, deparaffinized, rehydrated, and stained in an automated system (Ventana Benchmark ULTRA system; Roche, Tucson, AZ, USA) using commercially available detection kits and 1:250 dilutions of antibodies against TTF-1 (SPT24; Biocare), PD-L1 (28–8) (ab205921; Abcam, Cambridge, UK), VTCN1 (D1M8I; Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA), and B7-H3 (D9M2L; Cell Signaling Technology). All slides were stained within two months post-sectioning. The cutoff for positive staining of TTF-1, B7-H3, and VTCN1 was >1% at any intensity, and samples were dichotomized as positive or negative. For PD-L1, expression was evaluated by two pathologists on a quantitative scale from 0% to 100%.

4.5. Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables are reported as means and standard deviations. Categorical variables were compared by chi-squared test. To determine predictors of recurrence-free survival within the cohort, we constructed Cox proportional hazards models based on variables of interest. Recurrence-free survival was defined as the period from the day of operation to the day of recurrence or the day of final follow-up. Survival was assessed by the Kaplan–Meier method, and survival curves were compared by log-rank test. Multivariate analyses and calculations of hazard ratios and 95.0% confidence intervals were performed in JMP (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). Two-tailed p < 0.05 denoted statistically significant difference.

5. Conclusions

Based on our analysis of mutation profiles and genetic clustering, IMA is found to be a distinct entity from nonmucinous adenocarcinoma. Although IMA is considered to be difficult to treat, the immunohistochemistry data suggest that immunotherapy against B7-H3 may prove successful. Further studies are needed to validate our findings and to make them applicable to the clinical settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors greatly appreciate Hidetoshi Shigetomo, Takuro Uchida, and Yoshihiro Miyashita for helpful scientific discussion.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at http://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/10/12/478/s1, Figure S1: Immunostaining for VTCN-1 in IMA, NMA, and squamous cell carcinoma, Table S1: Clinical characteristics of the patients, Table S2: Mutations in IMA specimens, Table S3: Pathways affected in IMA and NMA by mutations with allele fractions ≥20%, Table S4: Sequencing targets.

Author Contributions

T.G. and T.N. wrote the manuscript. T.G., T.N., D.S., R.H., S.O., and Y.Y. performed the surgery. T.O., D.S., and R.H. carried out the pathological examination. Y.H., K.A., T.G., T.N., Y.Y., H.M., R.H., S.O., and M.O. participated in the genomic analyses. M.O. and Y.H. edited the final manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version for submission.

Funding

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Genome Research Project from Yamanashi Prefecture (to Y. Hirotsu and M. Omata) and by grants from Japanese Foundation for Multidisciplinary Treatment of Cancer (to T. Goto).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Travis W.D., Brambilla E., Noguchi M., Nicholson A.G., Geisinger K.R., Yatabe Y., Beer D.G., Powell C.A., Riely G.J., Van Schil P.E., et al. International association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society international multidisciplinary classification of lung adenocarcinoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2011;6:244–285. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e318206a221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Warth A., Muley T., Meister M., Stenzinger A., Thomas M., Schirmacher P., Schnabel P.A., Budczies J., Hoffmann H., Weichert W. The novel histologic international association for the study of lung cancer/american thoracic society/european respiratory society classification system of lung adenocarcinoma is a stage-independent predictor of survival. J. Clin. Oncol. 2012;30:1438–1446. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.37.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshizawa A., Motoi N., Riely G.J., Sima C.S., Gerald W.L., Kris M.G., Park B.J., Rusch V.W., Travis W.D. Impact of proposed iaslc/ats/ers classification of lung adenocarcinoma: Prognostic subgroups and implications for further revision of staging based on analysis of 514 stage i cases. Mod. Pathol. 2011;24:653–664. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hata A., Katakami N., Fujita S., Kaji R., Imai Y., Takahashi Y., Nishimura T., Tomii K., Ishihara K. Frequency of EGFR and KRAS mutations in japanese patients with lung adenocarcinoma with features of the mucinous subtype of bronchioloalveolar carcinoma. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2010;5:1197–1200. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181e2a2bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casali C., Rossi G., Marchioni A., Sartori G., Maselli F., Longo L., Tallarico E., Morandi U. A single institution-based retrospective study of surgically treated bronchioloalveolar adenocarcinoma of the lung: Clinicopathologic analysis, molecular features, and possible pitfalls in routine practice. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2010;5:830–836. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3181d60ff5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finberg K.E., Sequist L.V., Joshi V.A., Muzikansky A., Miller J.M., Han M., Beheshti J., Chirieac L.R., Mark E.J., Iafrate A.J. Mucinous differentiation correlates with absence of EGFR mutation and presence of KRAS mutation in lung adenocarcinomas with bronchioloalveolar features. J. Mol. Diagn. 2007;9:320–326. doi: 10.2353/jmoldx.2007.060182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kadota K., Yeh Y.C., D’Angelo S.P., Moreira A.L., Kuk D., Sima C.S., Riely G.J., Arcila M.E., Kris M.G., Rusch V.W., et al. Associations between mutations and histologic patterns of mucin in lung adenocarcinoma: Invasive mucinous pattern and extracellular mucin are associated with KRAS mutation. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 2014;38:1118–1127. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0000000000000246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shim H.S., Kenudson M., Zheng Z., Liebers M., Cha Y.J., Hoang Ho Q., Onozato M., Phi Le L., Heist R.S., Iafrate A.J. Unique genetic and survival characteristics of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2015;10:1156–1162. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0000000000000579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cox A.D., Fesik S.W., Kimmelman A.C., Luo J., Der C.J. Drugging the undruggable ras: Mission possible? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2014;13:828–851. doi: 10.1038/nrd4389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stephen A.G., Esposito D., Bagni R.K., McCormick F. Dragging ras back in the ring. Cancer Cell. 2014;25:272–281. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2014.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Manchado E., Weissmueller S., Morris J.P.T., Chen C.C., Wullenkord R., Lujambio A., de Stanchina E., Poirier J.T., Gainor J.F., Corcoran R.B., et al. A combinatorial strategy for treating KRAS-mutant lung cancer. Nature. 2016;534:647–651. doi: 10.1038/nature18600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kitai H., Ebi H., Tomida S., Floros K.V., Kotani H., Adachi Y., Oizumi S., Nishimura M., Faber A.C., Yano S. Epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition defines feedback activation of receptor tyrosine kinase signaling induced by mek inhibition in KRAS-mutant lung cancer. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:754–769. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ordonez N.G. Thyroid transcription factor-1 is a marker of lung and thyroid carcinomas. Adv. Anat. Pathol. 2000;7:123–127. doi: 10.1097/00125480-200007020-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cha Y.J., Shim H.S. Biology of invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung. Transl. Lung Cancer Res. 2017;6:508–512. doi: 10.21037/tlcr.2017.06.10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hwang D.H., Sholl L.M., Rojas-Rudilla V., Hall D.L., Shivdasani P., Garcia E.P., MacConaill L.E., Vivero M., Hornick J.L., Kuo F.C., et al. KRAS and NKX2-1 mutations in invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2016;11:496–503. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2016.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Winslow M.M., Dayton T.L., Verhaak R.G., Kim-Kiselak C., Snyder E.L., Feldser D.M., Hubbard D.D., DuPage M.J., Whittaker C.A., Hoersch S., et al. Suppression of lung adenocarcinoma progression by NKX2-1. Nature. 2011;473:101–104. doi: 10.1038/nature09881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maeda Y., Tsuchiya T., Hao H., Tompkins D.H., Xu Y., Mucenski M.L., Du L., Keiser A.R., Fukazawa T., Naomoto Y., et al. KRAS(g12d) and NKX2-1 haploinsufficiency induce mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung. J. Clin. Invest. 2012;122:4388–4400. doi: 10.1172/JCI64048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Snyder E.L., Watanabe H., Magendantz M., Hoersch S., Chen T.A., Wang D.G., Crowley D., Whittaker C.A., Meyerson M., Kimura S., et al. NKX2-1 represses a latent gastric differentiation program in lung adenocarcinoma. Mol. Cell. 2013;50:185–199. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2013.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo M., Tomoshige K., Meister M., Muley T., Fukazawa T., Tsuchiya T., Karns R., Warth A., Fink-Baldauf I.M., Nagayasu T., et al. Gene signature driving invasive mucinous adenocarcinoma of the lung. EMBO Mol. Med. 2017;9:462–481. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201606711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Pardoll D.M. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer. 2012;12:252–264. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keir M.E., Butte M.J., Freeman G.J., Sharpe A.H. Pd-1 and its ligands in tolerance and immunity. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2008;26:677–704. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.26.021607.090331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brahmer J.R., Tykodi S.S., Chow L.Q., Hwu W.J., Topalian S.L., Hwu P., Drake C.G., Camacho L.H., Kauh J., Odunsi K., et al. Safety and activity of anti-pd-l1 antibody in patients with advanced cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:2455–2465. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Topalian S.L., Sznol M., McDermott D.F., Kluger H.M., Carvajal R.D., Sharfman W.H., Brahmer J.R., Lawrence D.P., Atkins M.B., Powderly J.D., et al. Survival, durable tumor remission, and long-term safety in patients with advanced melanoma receiving nivolumab. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014;32:1020–1030. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.53.0105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ni L., Dong C. New b7 family checkpoints in human cancers. Mol. Cancer Ther. 2017;16:1203–1211. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li D., Wang J., Zhou J., Zhan S., Huang Y., Wang F., Zhang Z., Zhu D., Zhao H., Li D., et al. B7-h3 combats apoptosis induced by chemotherapy by delivering signals to pancreatic cancer cells. Oncotarget. 2017;8:74856–74868. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li Y., Yang X., Wu Y., Zhao K., Ye Z., Zhu J., Xu X., Zhao X., Xing C. B7-h3 promotes gastric cancer cell migration and invasion. Oncotarget. 2017;8:71725–71735. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu H., Wang X., Mo N., Zhang L., Yuan X., Lu Z. B7-homolog 4 promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transition and invasion of bladder cancer cells via activation of nuclear factor-kappab. Oncol. Res. 2018;26:1267–1274. doi: 10.3727/096504018X15172227703244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang J., Liu L., Han S., Li Y., Qian Q., Zhang Q., Zhang H., Yang Z., Zhang Y. B7-h3 is related to tumor progression in ovarian cancer. Oncol. Rep. 2017;38:2426–2434. doi: 10.3892/or.2017.5858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou D., Zhou Y., Li C., Yang L. Silencing of b7-h4 suppresses the tumorigenicity of the mgc-803 human gastric cancer cell line and promotes cell apoptosis via the mitochondrial signaling pathway. Int. J. Oncol. 2018;52:1267–1276. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2018.4274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Castellanos J.R., Purvis I.J., Labak C.M., Guda M.R., Tsung A.J., Velpula K.K., Asuthkar S. B7-h3 role in the immune landscape of cancer. Am. J. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2017;6:66–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Flem-Karlsen K., Fodstad O., Tan M., Nunes-Xavier C.E. B7-h3 in cancer—Beyond immune regulation. Trends Cancer. 2018;4:401–404. doi: 10.1016/j.trecan.2018.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Loo D., Alderson R.F., Chen F.Z., Huang L., Zhang W., Gorlatov S., Burke S., Ciccarone V., Li H., Yang Y., et al. Development of an fc-enhanced anti-b7-h3 monoclonal antibody with potent antitumor activity. Clin. Cancer Res. 2012;18:3834–3845. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Inamura K., Yokouchi Y., Kobayashi M., Sakakibara R., Ninomiya H., Subat S., Nagano H., Nomura K., Okumura S., Shibutani T., et al. Tumor b7-h3 (cd276) expression and smoking history in relation to lung adenocarcinoma prognosis. Lung Cancer. 2017;103:44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2016.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Proctor D.T., Patel Z., Lama S., Resch L., van Marle G., Sutherland G.R.J.O. Identification of pd-l2, b7–h3 and ctla-4 immune checkpoint proteins in genetic subtypes of meningioma. OncoImmunology. 2018:1–12. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1512943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zou W., Chen L. Inhibitory b7-family molecules in the tumour microenvironment. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2008;8:467–477. doi: 10.1038/nri2326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chapoval A.I., Ni J., Lau J.S., Wilcox R.A., Flies D.B., Liu D., Dong H., Sica G.L., Zhu G., Tamada K., et al. B7-h3: A costimulatory molecule for t cell activation and ifn-gamma production. Nat. Immunol. 2001;2:269–274. doi: 10.1038/85339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hofmeyer K.A., Ray A., Zang X. The contrasting role of b7-h3. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:10277–10278. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805458105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sun M., Richards S., Prasad D.V., Mai X.M., Rudensky A., Dong C. Characterization of mouse and human b7-h3 genes. J. Immunol. 2002;168:6294–6297. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.12.6294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Yi K.H., Chen L. Fine tuning the immune response through b7-h3 and b7-h4. Immunol. Rev. 2009;229:145–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2009.00768.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sun Y., Wang Y., Zhao J., Gu M., Giscombe R., Lefvert A.K., Wang X. B7-h3 and b7-h4 expression in non-small-cell lung cancer. Lung Cancer. 2006;53:143–151. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2006.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sun T.W., Gao Q., Qiu S.J., Zhou J., Wang X.Y., Yi Y., Shi J.Y., Xu Y.F., Shi Y.H., Song K., et al. B7-h3 is expressed in human hepatocellular carcinoma and is associated with tumor aggressiveness and postoperative recurrence. Cancer Immunol. Immunother. 2012;61:2171–2182. doi: 10.1007/s00262-012-1278-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yamato I., Sho M., Nomi T., Akahori T., Shimada K., Hotta K., Kanehiro H., Konishi N., Yagita H., Nakajima Y. Clinical importance of b7-h3 expression in human pancreatic cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2009;101:1709–1716. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gibbs A.R., Thunnissen F.B. Histological typing of lung and pleural tumours: Third edition. J. Clin. Pathol. 2001;54:498–499. doi: 10.1136/jcp.54.7.498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chansky K., Detterbeck F.C., Nicholson A.G., Rusch V.W., Vallieres E., Groome P., Kennedy C., KRASnik M., Peake M., Shemanski L., et al. The iaslc lung cancer staging project: External validation of the revision of the tnm stage groupings in the eighth edition of the tnm classification of lung cancer. J. Thorac. Oncol. 2017;12:1109–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2017.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive molecular profiling of lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2014;511:543–550. doi: 10.1038/nature13385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network Comprehensive genomic characterization of squamous cell lung cancers. Nature. 2012;489:519–525. doi: 10.1038/nature11404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Clinical Lung Cancer Genome Project. Network Genomic Medicine A genomics-based classification of human lung tumors. Sci. Transl. Med. 2013;5:209ra153. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3006802. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rudin C.M., Durinck S., Stawiski E.W., Poirier J.T., Modrusan Z., Shames D.S., Bergbower E.A., Guan Y., Shin J., Guillory J., et al. Comprehensive genomic analysis identifies sox2 as a frequently amplified gene in small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:1111–1116. doi: 10.1038/ng.2405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Peifer M., Fernandez-Cuesta L., Sos M.L., George J., Seidel D., Kasper L.H., Plenker D., Leenders F., Sun R., Zander T., et al. Integrative genome analyses identify key somatic driver mutations of small-cell lung cancer. Nat. Genet. 2012;44:1104–1110. doi: 10.1038/ng.2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Imielinski M., Berger A.H., Hammerman P.S., Hernandez B., Pugh T.J., Hodis E., Cho J., Suh J., Capelletti M., Sivachenko A., et al. Mapping the hallmarks of lung adenocarcinoma with massively parallel sequencing. Cell. 2012;150:1107–1120. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Govindan R., Ding L., Griffith M., Subramanian J., Dees N.D., Kanchi K.L., Maher C.A., Fulton R., Fulton L., Wallis J., et al. Genomic landscape of non-small cell lung cancer in smokers and never-smokers. Cell. 2012;150:1121–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Catalogue of Somatic Mutations In Cancer. [(accessed on 4 May 2014)]; Available online: http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cancergenome/projects/cosmic.

- 53.Hirotsu Y., Nakagomi H., Sakamoto I., Amemiya K., Oyama T., Mochizuki H., Omata M. Multigene panel analysis identified germline mutations of DNA repair genes in breast and ovarian cancer. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2015;3:459–466. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hirotsu Y., Nakagomi H., Sakamoto I., Amemiya K., Mochizuki H., Omata M. Detection of brca1 and brca2 germline mutations in japanese population using next-generation sequencing. Mol. Genet. Genomic Med. 2015;3:121–129. doi: 10.1002/mgg3.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goto T., Hirotsu Y., Amemiya K., Nakagomi T., Shikata D., Yokoyama Y., Okimoto K., Oyama T., Mochizuki H., Omata M. Distribution of circulating tumor DNA in lung cancer: Analysis of the primary lung and bone marrow along with the pulmonary venous and peripheral blood. Oncotarget. 2017;8:59268–59281. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.19538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goto T., Hirotsu Y., Oyama T., Amemiya K., Omata M. Analysis of tumor-derived DNA in plasma and bone marrow fluid in lung cancer patients. Med. Oncol. 2016;33:29. doi: 10.1007/s12032-016-0744-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goto T., Hirotsu Y., Nakagomi T., Shikata D., Yokoyama Y., Amemiya K., Tsutsui T., Kakizaki Y., Oyama T., Mochizuki H., et al. Detection of tumor-derived DNA dispersed in the airway improves the diagnostic accuracy of bronchoscopy for lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:79404–79413. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Amemiya K., Hirotsu Y., Goto T., Nakagomi H., Mochizuki H., Oyama T., Omata M. Touch imprint cytology with massively parallel sequencing (tic-seq): A simple and rapid method to snapshot genetic alterations in tumors. Cancer Med. 2016;5:3426–3436. doi: 10.1002/cam4.950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Iijima Y., Hirotsu Y., Amemiya K., Ooka Y., Mochizuki H., Oyama T., Nakagomi T., Uchida Y., Kobayashi Y., Tsutsui T., et al. Very early response of circulating tumour-derived DNA in plasma predicts efficacy of nivolumab treatment in patients with non-small cell lung cancer. Eur. J. Cancer. 2017;86:349–357. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Goto T., Hirotsu Y., Mochizuki H., Nakagomi T., Oyama T., Amemiya K., Omata M. Stepwise addition of genetic changes correlated with histological change from “well-differentiated” to “sarcomatoid” phenotypes: A case report. BMC Cancer. 2017;17:65. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3059-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nakagomi T., Goto T., Hirotsu Y., Shikata D., Yokoyama Y., Higuchi R., Amemiya K., Okimoto K., Oyama T., Mochizuki H., et al. New therapeutic targets for pulmonary sarcomatoid carcinomas based on their genomic and phylogenetic profiles. Oncotarget. 2018;9:10635–10649. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.24365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Nakagomi T., Goto T., Hirotsu Y., Shikata D., Amemiya K., Oyama T., Mochizuki H., Omata M. Elucidation of radiation-resistant clones by a serial study of intratumor heterogeneity before and after stereotactic radiotherapy in lung cancer. J. Thorac. Dis. 2017;9:E598–E604. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2017.06.02. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goto T., Hirotsu Y., Mochizuki H., Nakagomi T., Shikata D., Yokoyama Y., Oyama T., Amemiya K., Okimoto K., Omata M. Mutational analysis of multiple lung cancers: Discrimination between primary and metastatic lung cancers by genomic profile. Oncotarget. 2017;8:31133–31143. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.16096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ahr A., Holtrich U., Solbach C., Scharl A., Strebhardt K., Karn T., Kaufmann M. Molecular classification of breast cancer patients by gene expression profiling. J. Pathol. 2001;195:312–320. doi: 10.1002/path.955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.