Abstract

There is increasing recognition that culturally-based diabetes prevention programs can facilitate the adoption and maintenance of healthy behaviours in the communities in which they are implemented. The Kahnawake School Diabetes Prevention Project (KSDPP) is a health promotion, community-based participatory research project aiming to reduce the incidence of Type 2 diabetes in the community of Kahnawake (Mohawk territory, Canada), with a large range of interventions integrating a Haudenosaunee perspective of health. Building on a qualitative, naturalistic and interpretative inquiry, this study aimed to assess the outcomes of a suite of culturally-based interventions on participants’ life and experience of health. Data were collected through semi-structured qualitative interviews of 1 key informant and 17 adult, female Kahnawake community members who participated in KSDPP’s suite of interventions from 2007 to 2010. Grounded theory was chosen as an analytical strategy. A theoretical framework that covered the experiences of all study participants was developed from the grounded theory analysis. KSDPP’s suite of interventions provided opportunities for participants to experience five different change processes: (i) Learning traditional cooking and healthy eating; (ii) Learning physical activity; (iii) Learning mind focusing and breathing techniques; (iv) Learning cultural traditions and spirituality; (v) Socializing and interacting with other participants during activities. These processes improved participants’ health in four aspects: mental, physical, spiritual and social. Results of this study show how culturally-based health promotion can bring about healthy changes addressing the mental, physical, spiritual and social dimensions of a holistic concept of health, relevant to the Indigenous perspective of well-being.

Keywords: Aboriginal health, community-based participatory research, culture, disease prevention, health perception

INTRODUCTION

Indigenous peoples in North America experience a disproportionate burden of disease and morbidity (Gracey and King, 2009). Type 2 diabetes is one of the diseases that unequally affect Indigenous people in Canada and USA, compared with their non-Indigenous counterparts (Young et al., 2000; Alberti et al., 2007; Public Health Agency of Canada, 2011). This inequity can be understood as rooted in centuries of colonization by European settlers resulting, in complex and multiple ways, in the loss of traditional way of life and reduced health for Indigenous people (Kolahdooz et al., 2015). Colonization set up an oppressive context for Indigenous peoples characterized by the imposition of a dominant culture and an attempted cultural genocide via the residential school system, loss of traditional lands and forced resettlement to reserves, all creating social conditions of acculturation and poverty which frustrated Indigenous peoples rights to maintain, transfer and preserve their traditions and original lifestyles that contributed to physical, mental and spiritual health (Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2012; 2015; Kolahdooz et al., 2015).

There is increasing recognition that culturally-based diabetes prevention programs are key to overcome challenges related to the adoption and maintenance of healthy behaviours in the communities in which they are implemented (Satterfield et al., 2003; Attridge et al., 2014). A systematic review of culturally appropriate diabetes health education interventions in ethnic minority groups found that these initiatives can improve blood sugar control, health knowledge and lifestyle among participants up to 24 months after the intervention (Attridge et al., 2014). Culturally-based programs often tailor information and messages to participants, incorporate local perceptions and preferences, involve community or lay health workers in the design or implementation of the program, integrate traditional practices, knowledge and values in the intervention, use metaphors and stories as well as build on social and family assets (Watson et al., 2001; Eakin et al., 2002; Macaulay et al., 2003; Satterfield et al., 2003; Ho et al., 2006). A useful way to ensure cultural relevance of interventions consists in involving the community in the design and implementation of the intervention (Potvin et al., 2003). Some studies have emphasized the role of lay health workers (LHWs), community members working in professional capacity, in designing and delivering culturally-based diabetes prevention interventions (Williams et al., 2006; McCloskey, 2009). These studies have found that LHWs, because of their knowledge of the community infrastructure and relationship with community members, can identify and meet community needs in a culturally sensitive manner (McCloskey, 2009).

There is very limited literature that explores the contribution of culturally relevant interventions on health and wellness in the context of diabetes prevention. This paper aims to assess, from the perspective of the participants and in a holistic way, the outcomes of a suite of culturally-based diabetes prevention interventions on Indigenous participants’ health and life.

THE KAHNAWAKE SCHOOLS DIABETES PREVENTION PROJECT

Kahnawake is a Kanien’keha:ka (Mohawk) community of ∼8000 residents located 15 km from downtown Montreal (Canada). Kahnawake is part of the Mohawk Nation and the Iroquois or Haudenosaunee Confederacy, and had a traditional food system based on agriculture, gathering, hunting game and fishing (Macaulay et al., 1997; Macaulay et al., 2006). Although the community has a history of independence and autonomy (Bisset et al., 2004), the legacy of colonization has transformed traditional ways of living, and created environments that promote poorer food and lifestyle choices, explaining increases in obesity and diabetes promoting lifestyles in the community (Hovey et al., 2014).

In the late 1980s, baseline studies in Kahnawake documented rates of Type 2 diabetes at twice the national average and high rates of diabetic complications (Macaulay et al., 1988; Montour et al., 1989). Following community presentations disclosing these results, elders requested that ‘something be done’ (Bisset et al., 2004). As a result, community members, health professionals, educators and academics from McGill University and Université de Montréal collaboratively created the Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project (KSDPP) in 1994 (Macaulay et al., 1997; Macaulay et al., 2006). KSDPP, a health promotion, community-based participatory research project, comprises an Intervention team, a Research team, and a Community Advisory Board (CAB). The CAB is constituted from community members and supervises the operations of KSDPP, reviewing all intervention, research and training activities and ensuring research accountability to the community. The goal of KSDPP is to reduce the incidence of diabetes in the community with a focus on preventing childhood obesity and improving the health of future generations, by fostering positive healthy attitudes, healthy eating and physical activity. For instance, KSDPP developed school-based interventions for children, including a health education program that involves in-class physical activities, a Wellness Policy to promote healthy eating and physical activity in Kahnawake schools, an active school transportation program, as well as supporting programs for extended families and community ecological changes (Macaulay et al., 2006; Hogan et al., 2014; Macridis et al., 2016).

In 2007, the KSDPP Intervention Team developed a suite of complementary interventions to meet the needs of women who found it challenging to be physically active and to eat healthily, which are both key in the prevention of Type 2 diabetes. A lay health worker from Kahnawake, who was at that time a member of the KSDPP Intervention Team and designated the Community Intervention Facilitator (CIF), took the lead in designing the suite of interventions, which were reviewed by the full intervention team and CAB. Her status as a community member, traditional healer and traditional knowledge holder and her experience in the community brought significant credibility, expertise and cultural integrity to the interventions. She purposely built these interventions to address health holistically from a Haudenosaunee perspective promoting physical, mental and spiritual well-being, a concept called Ionkwatákarí:te, which means ‘we are healthy’ in the Mohawk language. This philosophy understands the interconnection of the physical body with spirit and life essence as crucial for enabling people to feel powerful, to know their worth and to care for themselves.

The suite of interventions included (i) ‘Healthy Mind in a Healthy Body’ Workshops, (ii) Gentle and Standard Yoga classes, (iii) ‘Haudenosaunee Foods Cooking’ Workshops, (iv) Fitness Program for Young Women/Mothers and (v) Qigong classes (see Table 1). Culturally-based aspects of these interventions involved teaching traditional Kanien’keha:ka practices and knowledge (traditional foodways, traditional medicines and spirituality), integrating cultural values and building on traditional learning styles such as storytelling. Although based on Eastern philosophies, Yoga and Qigong were selected for their holistic health approach that emphasizes a balance and a connection between body and mind, thus aligning with Haudenosaunee health philosophy. The interventions that are the objects of this study were held in Kahnawake from November 2007 to March 2010, and some of them (Yoga classes, Cooking Workshops, Fitness Programs) are still offered by KSDPP today.

Table 1:

Interventions description

| Interventions | Activities | Objectives |

|---|---|---|

| Healthy Mind in a Healthy Body Workshops (Includes five sessions over a few weeks, held twice from August 16th to 25th, 2008 and from September 14th to October 19th, 2009) | Lecture series on healthy nutrition, traditional foods, physical activity, diabetes prevention, mental and spiritual health | To promote positive lifestyle changes to young mothers and adult community members |

| Yoga classes (standard and gentle) (Weekly, from October 7th, 2008 to February 22nd, 2010) | Mild physical poses and breathing exercises | To promote fitness, relaxation and peace of mind of adult community members |

| Haudenosaunee Foods Cooking Workshops (Held intermittently, depending on funding and available time from November 16th, 2007 to 2010) | Cooking skills development activities, teaching cooking of traditional foods | To teach adult community members how to make healthy meals using traditional Haudenosaunee foods |

| Fitness Program for Young Women/Mothers (Weekly, from April 1st, 2009 to March 31st, 2010) | Free Kahnawake Youth Center membership (access to the weight and exercise room), weekly fitness program sessions, and one session with a personal trainer | To assist women to develop a routine of physical activity and a support network between participants |

| Qigong classes (Weekly, from January 7th, 2008 to March 31st, 2008) | Meditation, breathing exercises, guided imagery and mild physical activity | To help adult community members to cultivate a vital life-force |

Following the implementation of these interventions, in 2010 KSDPP decided to explore the outcomes from participants, recognising how this approach could improve the design and implementation of future interventions. This study aims to answer this question: ‘How do the KSDPP interventions, as a suite of culturally-based health promoting interventions, change how participants experience their life?’

METHODS

General approach and design

This study is a qualitative, naturalistic and interpretative inquiry (Corbin and Strauss, 2008) exploring Indigenous participants’ accounts of their experiences with a suite of culturally-based health promoting interventions founded upon a Haudenosaunee holistic health philosophy. The research question aimed to guide the development of a theory for understanding participants’ experiences and the meanings they attach to them.

This study was situated in the KSDPP, which uses formalized principles of participatory research as a general approach (Macaulay et al., 1997; Macaulay et al., 1997). Accordingly, the principal investigator (PI) developed the research question and the guiding interview questions, collected and analysed the data with continuous discussion and guidance from the KSDPP Research Team, the KSDPP Community Advisory Board and her academic supervisory committee. This study was first approved by the KSDPP Community Advisory Board via their Review and Approval Process for Ethically Responsible Research and then by the McGill University Faculty of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences Research Ethics Board.

Participants, sampling and recruitment

The PI interviewed 17 adult, female Kahnawake community members (out of 21 contacted) who participated in KSDPP’s suite of interventions from 2007 to 2010. She employed purposeful intensity sampling to select information-rich cases based on their experiences with the phenomenon of interest. Those included participants who participated repeatedly in more than one of the offered interventions, and who were deemed to have a wider experience of the suite of interventions (Patton, 2002). The CIF used attendance records to identify potential study participants and invited them by telephone. The PI completed enrolment by telephone. Once the 17 interviews were analysed it was determined that theoretical saturation had occurred since no new concepts emerged in the last few interviews and the relationships between concepts and their properties and dimensions were clear and developed in depth (Corbin and Strauss, 2008). The CIF, who designed and led the programs since 2007, was designated as a key informant and was interviewed to gather her interpretation of how the participants experienced the interventions and describe with more details the context of the experiences and the interventions. The sampling size was thus 18, including the key informant.

3.3 Data collection

Semi-structured interviews were conducted by the PI with each participant following an interview guide approach with discussion topics (Patton, 2002). The interviews sought to learn how participants experienced the interventions, what these experiences meant to them and what changes, if any, they experienced following these experiences. Demographic questions collected information on age, and instance of participation in each of the interventions. On average, interviews lasted 54 min (range 23–141 min). As mentioned above, the CIF’s interview helped to validate data collected from the participants. Interviews were audio-recorded, and then transcribed manually into text. During one interview a participant did not wish a portion of her interview recorded, but allowed notes to be taken by the researcher.

Data analysis

Grounded theory was chosen to construct a theory related to the phenomenon being studied (Corbin and Strauss, 2008). The Ethnograph version 6.0 facilitated data analysis. Following the tenets of Grounded Theory, data analysis started after the first set of interviews was conducted. The PI started by micro analyzing five interviews, a process involving line-by-line open coding of all emergent concepts (Corbin and Strauss, 2008). Concepts (themes) were elaborated in terms of their properties (characteristics of concepts) and dimensions (variations in properties). Subsequent interview texts were then analysed and coded. Extensive diagramming and constant comparisons were performed to map and integrate participants’ experiences of the interventions, in order to forge the propositions of the grounded theory (selective coding) (Corbin and Strauss, 2008). Theoretical saturation was deemed to have occurred when no new concepts emerged and relationships between concepts and their properties and dimensions were clear and well developed (Corbin and Strauss, 2008).

A theoretical framework that covered the experiences of all study participants was developed from the grounded theory analysis. The concepts, their dimensions and properties have been systematically organized according to the interventions’ components (activities undertaken by the participants in the different interventions), change processes (broad categories of change experienced by participants), outputs (what was directly produced through interventions activities according to participants) and effects (benefits, changes in participants’ experience that resulted from the outputs).

Validity of the study results was achieved through triangulation of sources through member checks with a subgroup of participants and the CIF as a key informant; peer examination via the supervisory committee and the KSDPP Research Team; and by following a participatory and collaborative research approach involving a high level of engagement from the KSDPP Intervention Team (Corbin and Strauss, 2008). Reliability was accomplished by documenting and performing precise work in keeping with the tenets of grounded theory (Corbin and Strauss, 2008).

RESULTS

Participants description and background

Participants mean age was 47 years (SD 15) ranging from 25 to 69 years. Participants interviewed had a total of 46 instances of participation (mean of 2.7 interventions by participant).

Participants related experiencing several personal challenges before deciding to participate in a KSDPP activity. Most of them felt they lacked traditional knowledge as well as healthy lifestyle skills, and they experienced stress, isolation and health problems. Participants felt they did not know enough about the beliefs, values, customs, spirituality and cultural history of Kanien’kehá:ka in order to participate in cultural traditions. They felt unable to partake in healthy lifestyles because they lacked skills including knowing how to cook, how to and where to grocery shop for healthy food and how to perform physical activities. Health problems experienced by participants included the physical effects of illness, injury and aging. Stress was experienced by participants as a dialectical tension creating worry, a sense of burden and concern due to feeling overwhelmed with the busy tasks of daily living and external events or circumstances in the community. Some older participants felt isolated due to age related decreased mobility, a few women talked about being lonely and young mothers felt isolated at home with their young children.

Processes: five major change processes experienced by participants of the interventions

KSDPP’s suite of interventions provided opportunities for participants to experience different change processes, which enabled them to overcome, manage or cope with their personal challenges. The experiences of the participants were organized into five change processes/pathways (each with specific outputs and effects): (i) Learning traditional cooking and healthy eating; (ii) Learning physical activity; (iii) Learning mind focusing and breathing techniques; (iv) Learning cultural traditions and spirituality; (5) Socializing and interacting with other participants during activities. Table 2 synthesizes and underlines the links between each category of concepts in order to reconstitute change pathways from the participants’ perspective.

Table 2:

Change processes experienced by participants of the interventions

| Intervention components | Processes: changes experienced in the interventions |

Consequences: perceived outcomes of the interventions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activities | Change processes | Outputs | Effects |

| Lecture on healthy nutrition and traditional food, cooking skills development activities, traditional food cooking teaching | 1. Learning traditional cooking and healthy eating | − New skills to cook their own food | − Feelings of pride and accomplishment |

| − New skills to make healthy food choices | − Value healthy eating and cooking | ||

| Mild physical activity, fitness | 2. Learning physical activity | − New skills to perform physical activities | − Feeling of pride and accomplishment |

| − Confidence to perform physical activities | − Physical benefits, such as increased strength, flexibility, balance, weight-loss and pain relief | ||

| − Become physically active | |||

| Mild physical activity, meditation, breathing exercises, and guided imagery | 3. Learning mind focusing and relaxation techniques | − Being mindful | − Positive feelings of a calm mind, increased energy, patience, relaxation and better mood |

| − New stress coping skills | |||

| − Fulfillment of spiritual needs | |||

| − Stress and pain relief, sense of readiness to confront stressors and personal empowerment | |||

| Lectures on traditional foods, traditional medicines, mental and spiritual health, traditional food cooking, meditation, breathing exercises, guided imagery | 4. Learning cultural traditions and spirituality | − New knowledge of traditional foodways and skills to cook traditional food | − Feelings of connection with ancestors, history and culture |

| − Sense of cultural and social identity | |||

| − New knowledge of traditional medicines | − Positive feelings, happiness | ||

| − Fulfillment of spiritual needs | |||

| − New spiritual knowledge and spiritual guidance | |||

| Group format of sessions and workshops | 5. Socializing and interacting with others during activities | − New social connections | − Sense of group belonging |

| − Break down isolation | − Pleasure | ||

Learning traditional cooking and healthy eating

Learning and acquiring food skills was a process facilitated through various interventions’ components, such as lectures on healthy nutrition and traditional food, cooking skills development activities and cooking lessons in KSDPP interventions (mainly the Healthy Mind in a Healthy Body and the Haudenosaunee Foods Cooking Workshops). Through this, participants learned how cook their own food, to make healthy food choices and to value healthy eating and cooking their own food. A participant described this process as follows:

… well it's different for me, but I don't know how to cook. [Laugh.] … Well my friend she's making fun of me. She said, ‘Come on you gotta get your hands dirty,’ and stuff like that. [Laughs.] … And it was kind of embarrassing. But then I did, I started to learn. I learned, even like, to wash potatoes when you're using just the peelings on it. Like to really scrub it

Another participant explained how the workshops developed her skills to make healthy food choices:

‘Cause I only realized after I did the workshops how I was already just automatically changin’ my grocery shoppin'. I guess I would just think back and be like, ‘Oh yeah, okay. Okay I'm not gonna get that. I'm not gonna get this. I'm gonna get this instead.’

Experiences in the interventions influenced participants to make decisions to cook healthier food for themselves, their families, friends and other community members. Although learning food skills is usually conceived as influencing health behaviors, participants did not report this kind of outcome, but mostly reported feelings of accomplishment and pride, which were evident in the description of their own and others’ enjoyment of the food they had prepared. With new food skills, many participants came to value cooking on their own and eating healthy, which changed their attitude toward food choices, as evidenced in this quote:

‘Cause it drives me nuts when, if I go to eat with other people, like my friends and their kids, they have just a slice of pizza. Like if we go to a buffet. A slice of pizza and they'll get some French fries on their plate. It probably wouldn’t have bothered me if I didn’t take these workshops.

Learning physical activity

Learning physical activity was a change process facilitated by performing mild physical activity and fitness in the interventions, and was characterized by different outputs including learning skills to be physically active, building confidence and being active. In fact, by performing physical activities, participants learned the skills and gained the confidence to be physically active, which ultimately led to a sense of accomplishment and pride.

But other than learning something, simply being active in the interventions led many participants to experience several physical health benefits, including: perceived increased strength, flexibility and balance, weight-loss and less pain. A participant described the moment when she realized her strength had improved:

I moved this summer. And I had to haul, you know, quite a number of things. Boxes. Bins. You know, that kind of thing. And it occurred to me at some point that I was able to do those things … I mean I did attribute it to the yoga.

Another participant, who was experiencing chronic pain, explained how taking part in an intervention led her to experience pain relief:

I was in a lot of pain. And the physiotherapist suggested different exercises, maybe five or six, and I couldn’t do any of them. Every one of them caused me pain. … But since I’ve started going to yoga, I don’t take the medication every day.

Learning mind focusing and relaxation techniques

Learning mind focusing and relaxation techniques is another change process that participants experienced through mild physical activity, meditation, breathing exercises and guided imagery components of the interventions (mostly the gentle and standard Yoga classes and Qigong classes). The direct outputs of this process varied from experiencing a focused mind to developing stress coping skills. In fact, participants reported that their minds became focused on exercises and breathing while performing physical activity, preventing them from thinking about their concerns and encouraging feelings of well-being. For participants, being mind focused involved not thinking about sources of stress such as personal problems, tasks of everyday living or worrying about how classmates perceived participants’ ability to perform the physical activity in the interventions:

Major, major stress relief at the gym … It [the Women’s Fitness Program] really does help you relieve a lot of stress and you feel good after you leave. I'm like yeah, you did something for yourself. You feel good about yourself.

In the same way, other participants described experiencing positive feelings of calm mind, increased energy, patience, relaxation and better mood during their participation in the interventions. One older participant explained how taking part in these interventions gave her more energy to carry on her daily activities and take part in leisure time activities:

Well, what I notice right after the class, I can go shopping. … I went shopping after yoga. Then I went to the movies and that's not like me. I only do one or two things a day. But that day I did three. And I never went to bed till like eleven o'clock!

One of the most significant outputs of taking part in these interventions was that some participants developed skills to face and manage their stress and ultimately a sense of readiness to confront sources of stress in their lives.

It [the Women’s Fitness Program] just like makes you feel more … ah capable and able … It gives like an energy push like. I can do that! I can take that on today!

Following their participation in the intervention, some participants felt it was easier to decide how they truly thought and felt about their problems and could then make better decisions. A participant explained how she found this process empowering:

… If you have something difficult in your life and whatever, you feel powerless, but when you do certain exercise, like I did a weight training and this [Yoga] and if it involves power, then you got some power somewhere.

Last, one participant evoked her new stress coping skills as a way to relieve physical pain. She explained how she used the breathing techniques from Yoga to help her cope with acute pain after surgery:

I couldn't even cry, it hurt so much. So then I just did, from the yoga, the deep [breathing], … ' Cause I didn't even wanna know, did they make an incision? Or did they, were they able to do the robotic? But okay, I say: oh God just do that deep breathing through my nose. And I fell asleep.

Learning cultural traditions and spirituality

Through the different intervention activities that integrated Mohawk traditions and spirituality, participants also came to learn more about their culture, history and spirituality. More specifically, many participants mentioned having acquired traditional knowledge of foods and remedies, as well as spirituality, which some did not have due to the process of colonization:

Because we lost so much. ( … ) And then when you finally know some things, you're like, ‘Wow! Really? That's where I come from? That's what we did? And I'm doin' it now!’ … Even though everything was taken and gone. And we could still do it because people still know

By learning about traditional foods, remedies and spirituality and partaking in the same activities as their ancestors, participants had opportunities to connect with their cultural identity, history and spirituality. The Haudenosaunee Foods Cooking Workshops gave a woman a special opportunity to participate in her culture with her grandfather, and connect with her ancestor’s traditions:

I was so happy ‘cause I was able to take leftovers [traditional cornbread] home. And I brought my grandfather a plate. ( … ) And he’s like, ‘Oh my goodness! I didn't have this since my mother was alive.’ Yeah! So it was really nice ‘cause I was kind of showing him that I’m trying [to learn her traditions].

Participants positively experienced this new knowledge and the connection with traditions it provided. This participant explained how she experienced cooking with squash (a traditional food):

That was the first time I ever actually used squash … Yeah. In soup and 'cause … before that I never actually did it myself. I never even touched it or washed it or nothing like that until she did it with us … It makes me happy. [Laughs.]

Some participants mentioned having found spiritual guidance in the KSDPP interventions. A few participants felt that mental focusing that was promoted in the Yoga and Qigong classes was a spiritual experience compatible with traditional Mohawk spirituality. However, some women expressed that ‘the mix of mysticism and philosophies’ presented in the various KSDPP interventions did not mesh with their views. This could be related to the current diversity of beliefs in the community.

Socializing and interacting with others during activities

Last, according to their social and participative nature, and to a whole range of implementation conditions that facilitated womens’ participation (such as accommodating participants’ schedule and babysitting needs, and the affordable price of the interventions), the KSDPP interventions gave women opportunities to break their social isolation, meet new people and create supportive relationships with other community members:

When I got a little more information about it [the Cooking Workshops] I really was anticipating to come 'cause my daughter would be watched and I could cook and I could hang out with my friends and I could be out. You know? Be out! Be a part of the community again. Not at home doing nothing.

Participants reported sharing talking about commonalities and their lives, with friends and other women they did not normally see. They mentioned that participating in activities and interacting with each other allowed them to laugh, experience a good time and a sense of group belonging. In fact, a sisterly, family atmosphere developed between participants, especially at the Haudenosaunee Foods Cooking Workshops:

One day when I went they were all cutting vegetables and they were laughing and telling stories and the kids were right in front of them and their hands were going. Kids were putting stuff into bowls. One mother was feeding her baby and changing diapers and washing. And then somebody would hold the baby while she did something. … It looked like a family gathering rather than a workshop.

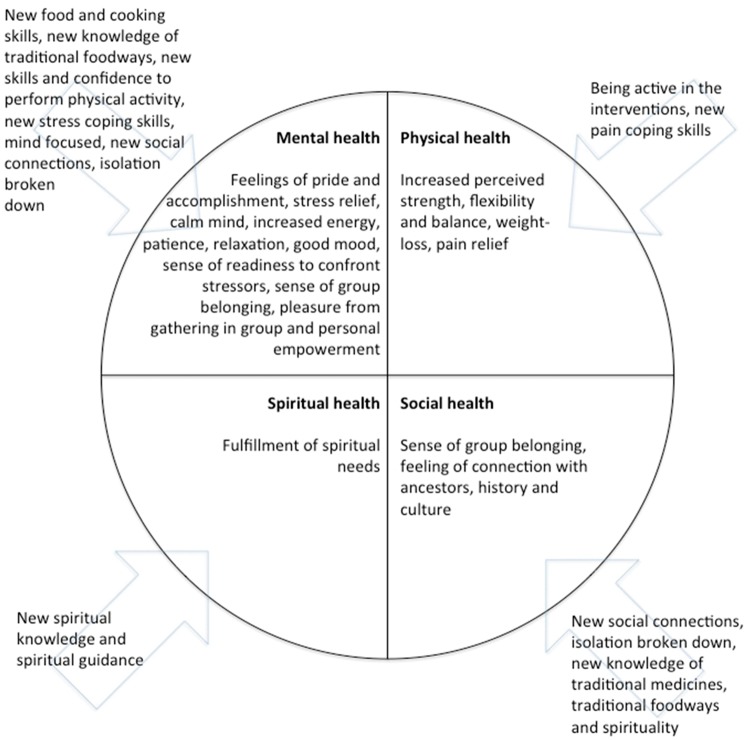

Consequences: perceived outcomes of the interventions

The five change processes experienced by participants (relating to traditional cooking and healthy eating, physical activity, mind focusing and relaxation, traditions and spirituality, as well as group gathering) were perceived to have improved their health in four different aspects. These included improved perceived mental, physical, spiritual and social aspects of health (Figure 1).

Fig. 1:

Four dimensions of health improved by the suite of interventions.

First, mental health was perceived as improved through feelings of pride and accomplishment that participants gained from developing and improving cooking and physical activity skills. This aspect of health was enhanced by experiencing stress relief, positive feelings of relaxation and a sense of readiness to confront stressors, as effects from learning stress coping skills and experiencing mind focusing in the interventions. Also, pleasure from gathering in groups in the different interventions seems to have impacted the mental well-being of participants.

Second, on another level, the physical aspect of participants’ health has been perceived as enhanced through being active in the interventions, which brought increased strength, flexibility, balance, weight-loss and pain relief to the participants. Also, learning stress coping skills in the interventions allowed some participant to manage their physical pain, which relates to an improved physical well-being.

Third, some participants perceived that the spiritual aspect of their health improved by receiving guidance, learning Mohawk spirituality in the interventions, and practicing mind focusing activities, which are sometime considered as a form of spiritual pursuit. These outputs of the interventions led to spiritual development for some. This is not a generalizable result, however, as certain participants expressed in the interviews.

Finally, the sense of group belonging that flowed from making new social connections and breaking down social isolation was not only relevant to the mental dimension of health, but also increased the social health of participants. By creating new relationships and a sense of group belonging, participants have increased their capacity to use social resources and capital that promotes leading a socially productive life. But the social dimension of participants’ perceived health was also increased through connecting with ancestors, history and cultural identity, which was reported as an effect of the interventions. In this perspective, social health was also linked to the cultural identity aspect of individual well-being, which related to the participant’s capacity to connect to and value their cultural and social identity.

DISCUSSION

Holistic health in four dimensions

Interestingly, the four dimensions of health that emerged from the analysis of data are very close to the four quadrants of the ‘medicine wheel’. Although it is not part of original Mohawk tradition, the medicine wheel was successfully used to promote health by a physician from Kahnawake and is an accepted model in this community (Montour, 2000). The four quadrants of the medicine wheel represent individual elements including the spiritual, physical, emotional and intellectual self. People who live a balance between these elements are thought to be happy, productive and capable of sharing, caring, trusting and respecting others (Meadows, 1990; Montour, 2000). When the balance is maladjusted it is traditionally thought to be the cause of, and to result in, poor health. In this study, results naturally emerged showing transformations in participants’ perceived mental, physical, spiritual and social dimensions of health, almost in accordance with the medicine wheel’s concept of holistic health (Figure 1)—except for the social dimension of health. A plausible explanation for these results may lie in the fact that the CIF, who designed the suite of interventions, is a traditional leader in the community. She built the intervention program following a Haudenosaunee perspective of health, addressing each of these aspects of health for participants. Results from this study, i.e. participants’ perceived outcomes of these interventions, confirm that her intentions have been realized. Moreover, these results highlight and reinforce the cultural relevance of KSDPP’s suite of interventions.

The interventions were intentionally designed to be culturally appropriate, for instance by including traditional practices and knowledge. The results of this study suggest that, by taking part in culturally-based interventions, participants developed and improved the social dimension of their health, not only by creating new social connections and breaking down their isolation, but also by enhancing their cultural collective identity through learning more about their traditions, history and culture in the KSDPP interventions. Even if not directly investigated in this study, we hypothesize that cultivating a sense of cultural identity in interventions directed at specific populations such as Indigenous communities may foster a holistic concept of health relevant to diabetes prevention. This can be related to Chandler and Lalonde’s (1998, 2008) studies, which link cultural continuity in First Nations communities to reduced suicide rates. According to these authors, personal and cultural continuity are deeply intertwined with key identity-preserving practices, which engage an individual or a community past and future in a coherent temporal and biographical frame (Chandler and Lalonde, 1998, 2008). Chandler and Lalonde (1998, 2008) found out that suicide rates were lower within communities that have managed to preserve or restore cultural aspects of their collective identity, such as government, land, education, health, community services, and cultural facilities. We think that the argument that is made by these authors about the importance of cultural continuity for personal persistence or self-continuity could be translated to self-esteem and self-care in the context of healthy habits and diabetes prevention. This suggests exploring the potential and power of activities emphasizing a community’s history and culture in fostering self-preserving behaviors, healthy habits and diabetes prevention.

In the same way, traditional spirituality can be considered as a specific aspect of culture that should be investigated for its potential links with self-care, healthy lifestyle and ultimately, diabetes prevention. By making space for Mohawk spirituality and traditional beliefs, KSDPP’s suite of interventions improved many participants’ perception of their spiritual health, which is integral to a holistic well-being from a Haudenosaunee perspective. As some authors suggest, health promotion intervention design should recognize the importance that Indigenous people place on spirituality and its relationship to health (Carter et al., 1997; Armstrong, 2000; Bachar et al., 2006). Some diabetes prevention interventions in Indigenous communities have included elements of traditional spirituality in their design, but to our knowledge none have investigated the effects on spiritual aspect of participants’ health (Armstrong, 2000; Bachar et al., 2006; Carter et al., 1997). Future studies of diabetes prevention interventions may want to examine whether Indigenous people experience a better balance in other areas of health (i.e. mental and physical) if spiritual health is improved. However, we should also acknowledge that there is a diversity of spiritual beliefs in Indigenous communities today, and that not all will connect with traditional belief systems.

Limitations of the interventions

Finally, weaknesses of this suite of interventions need to be identified and discussed, to provide useful lessons to those interested in implementing such initiatives. One first observation that has been discussed previously is that traditional spirituality doesn’t necessarily resonate with spiritual views of participants, given the diversity of religious beliefs in many communities. This pinpoints the importance of being respectful of differing spiritual beliefs. Another observation is that participants had preference for different learning styles, which did not always match the intervention’s favored style. For instance, one participant that attended many interventions explained in the interview that she preferred the hands-on style of the Cooking Workshops and the Women’s Fitness Program. She stopped attending the Healthy Mind in a Healthy Body Workshops because she felt it involved too much sitting and listening. This highlights the importance of varying learning styles inside a same intervention to reach and motivate the learners. More generally, there was limited attendance at some sessions. Despite the implementation of a whole range of conditions to facilitate womens’ participation (described previously), participants that ceased to participate in the interventions cited reasons that were mainly logistical, including the timing of the interventions, lack of personal time to attend, but also health problems which prevented them from participating in the interventions. Also, one important limit of this suite of interventions is that they relied almost entirely upon a charismatic CIF with strong leadership qualities, able to communicate traditional Haudenosaunee values and knowledge. Thus, some of the interventions (i.e. Healthy Mind in a Healthy Body Workshops and Qigong classes) stopped after the CIF left. This underlines the need to plan for sustainability in the interventions by training new leaders who embody cultural values, are able to master cultural content and who can successfully take on the work initiated by others. This could imply training some of the most committed participants, who have already experienced the interventions.

Limitations of the results

The results of this study are specific to women living in a Mohawk community close to a large urban centre. Their lives, culture and experiences may differ greatly from the lives of other Indigenous people. The fact that participants self-selected to join the KSDPP interventions could make them somehow different from the rest of the community. Also, we targeted participants showing deeper engagement with KSDPP’s suite of interventions (i.e. participation in more than one intervention), who may differ from other participants. Participants are subject to memory bias, which could impede their capacity to clearly recall the change processes they have undergone. In addition, a social desirability bias may have interfered with the results, but the interviewer strove to maintain neutrality throughout the interview process.

CONCLUSION

This study, which focuses comprehensively on participants’ experiences of culturally-based interventions intending to prevent Type 2 diabetes, is an original contribution to the literature in this field. Most of the time, studies aspire to report the effect of health promoting or preventive interventions on clinical markers of diabetes, diabetes prevalence and health behaviors of participants, without holistically investigating the participants’ experiences, the culturally-based aspect of the interventions and the impact on the perceived well-being of participants (Satterfield et al., 2003; Alberti et al., 2007). Results of this study show how culturally-based health promotion can bring about healthy changes addressing the mental, physical, spiritual and social dimensions of a holistic concept of health, relevant to the Indigenous perspective of well-being. These findings also highlight the importance of community participation and involvement of cultural knowledge holders in designing culturally-based interventions with Indigenous communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The principal investigator would like to thank the study participants, the Community Intervention Facilitator, KSDPP, the community of Kahnawake, the supervising professor and supervisory committee for their support of and contributions to this study.

FUNDING

This work was supported by a Master’s Fellowship provided to the principal investigator by the Anisnabe Kekendazone – Ottawa Network Environment for Aboriginal Health Research (NEAHR) that was funded by the Institute of Aboriginal Peoples’ Health, Canadian Institutes of Health Research.

REFERENCES

- Alberti K. G. M. M., Zimmet P., Shaw J. (2007) International Diabetes Federation: a consensus on Type 2 diabetes prevention. Diabetic Medicine, 24, 451–463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong D. (2000) A community diabetes education and gardening project to improve diabetes care in a Northwest American Indian tribe. Diabetes Education, 26, 113–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Attridge M., Creamer J., Ramsden M., Cannings-John R, Hawthorne K. (2014). Culturally appropriate health education for people in ethnic minority groups with type 2 diabetes mellitus. The Cochrane Library. W. Sons: 591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Bachar J., Lefler L., Reed L., McCoy T., Bailey R., Bell R. (2006) Cherokee choices: a diabetes prevention program for American Indians. Preventing Chronic Disease, 3, 1–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisset S., Cargo M., Delormier T., Macaulay A. C., Potvin L. (2004) Legitimizing diabetes as a community health issue: a case analysis of an Aboriginal community in Canada. Health Promotion International, 19, 317–326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter J., Gilliland S., Perez G., Levin S., Broussard B. A., Valdez L.. et al. (1997) Native American diabetes project: designing culturally relevant education materials. Diabetes Education, 23, 133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandler M. J., Lalonde C. (1998) Cultural continuity as a hedge against suicide in Canada’s first nations. Transcultural Psychiatry, 35, 191–219. [Google Scholar]

- Chandler M. J., Lalonde C. (2008). In Kirmayer L., Valaskis G. (eds), Cultural Continuity as a Moderator of Suicide Risk Among Canada’s Frist Nations. Healing Traditions: The Mental Health of Aboriginal Peoples in Canada. Vancouver, BC, University of British Columbia Press, pp. 221–248. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin J., Strauss A. (2008). Basics of Qualitative Research, Techniques and Procedures for Developing Grounded Theory, 3rd edition. Sage Publications, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Eakin E. G., Bull S. S., Glasgow R. E., Mason M. (2002) Reaching those most in need: a review of diabetes self-management interventions in disadvantaged populations. Diabetes/Metabolism Research and Reviews, 18, 26–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracey M., King M. (2009) Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. The Lancet, 374, 65–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho L. S., Gittelsohn J., Harris S. B., Ford E. (2006) Development of an integrated diabetes prevention program with First Nations in Canada. Health Promotion International, 21, 88–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan L., Bengoechea E. G., Salsberg J., Jacobs J., King M., Macaulay A. C. (2014) Using a participatory approach to the development of a school-based physical activity policy in an indigenous community. Journal of School Health, 84, 786–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hovey R., Delormier T., McComber A. M. (2014) Social-relational understandings of health and well-being from an Indigenous Perspective. International Journal of Indigenous Health, 10, 35–54. [Google Scholar]

- Kolahdooz F., Nader F., Kyoung J. Y., Sharma S. (2015) Understanding the social determinants of health among indigenous Canadians: priorities for health promotion policies and actions. Global Health Action, 8, 16.. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay A. C., Cargo M., Bisset S., Delormier T., Lévesque L., Potvin L.. et al. (2006). In Ferreira M. L., Lang G. C. (eds), Community empowerment for the Primary Prevention of Type II diabetes: Kanien’kehá:ka (Mohawk) ways for the Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project. Indigenous Peoples and Diabetes: Community Empowerment and Wellness. Carolina Academic Press, Durham, NC, pp. 407–458. [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay A. C., Delormier T., McComber A., Cross E., Potvin L., Paradis G.. et al. (1997) Participatory research with native community of Kahnawake creates innovative Code of Research Ethics. Canadian Journal of Public Health. Revue Canadienne de Sante Publique, 89, 105–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay A. C., Harris S. B., Lévesque L., Cargo M., Ford E., Salsberg J.. et al. (2003) Primary prevention of type 2 diabetes: experiences of 2 aboriginal communities in Canada. Canadian Journal of Diabetes, 27, 464–475. [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay A. C., Montour L. T., Adelson N. (1988) Prevalence of diabetic and atherosclerotic complications among Mohawk Indians of Kahnawake, PQ. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 139, 221–224. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay A. C., Paradis G., Potvin L., Cross E. J., Saad-Haddad C., McComber A.. et al. (1997) The Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project: intervention, evaluation, and baseline results of a diabetes primary prevention program with a native community in Canada. Preventive Medicine, 26, 779–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macridis S., Bengoechea E. G., McComber A. M., Jacobs J., Macaulay A. C. (2016) Active transportation to support diabetes prevention: Expanding school health promotion programming in an Indigenous community. Evaluation and program planning 56, 99–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey J. (2009) Promotores as partners in a community-based diabetes intervention program targeting Hispanics. Family Community Health, 32, 48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meadows K. (1990). The Medicine Way: How to live the Teachings of the Native American Medicine Wheel. Elements Books Limited, Shaftesbury, Dorset, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Montour L. T. (2000) The Medicine Wheel: Understanding “problem” patients in primary care. The Permanente Journal, 4, 34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Montour L. T., Macaulay A. C., Adelson N. (1989) Diabetes mellitus in Mohawks of Kahnawake, PQ: a clinical and epidemiologic description. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 141, 549–552. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton M. Q. (2002). Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, CA. [Google Scholar]

- Potvin L., Cargo M., McComber A., Delormier T., Macaulay A. C. (2003) Implementing participatory intervention and research in communities: lessons from the Kahnawake Schools Diabetes Prevention Project in Canada. Social Sciences and Medicine, 56, 1295.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Public Health Agency of Canada. (2011). Diabetes in Canada: Facts and Figures from a Public Health Perspective 2011. Public Health Agency of Canada; Ottawa, Government of Canada. [Google Scholar]

- Satterfield D. R., Volansky M., Caspersen C. J., Engelgau M. M., Bowman B. A., Gregg E. W.. et al. (2003) Community-based lifestyle interventions to prevent type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 26, 2643–2652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada. (2012; 2015). Calls to Action. Winnipeg, Manitoba, TRC of Canada.

- Watson J., Obersteller E. A., Rennie L., Whitbread C. (2001) Diabetic foot care: developing culturally appropriate educational tools for aboriginal and torres strait islander peoples in the Northern Territory, Australia. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 9, 121–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams J. H., Auslander W. F., Groot M. D., Robinson A., Houston C., Haire-Joshu D. (2006) Cultural relevancy of a diabetes prevention nutrition program for African American women. Health Promotion Practice, 7, 56–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young T. K., Reading J., Elias B., O’Neil J. D. (2000) Type 2 diabetes mellitus in Canada’s First Nations: status of an epidemic in progress. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 163, 561–566. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]