Abstract

Objective:

Examine 1) whether observed social reinforcements (i.e., “likes”) received by peers’ alcohol-related social media posts are related to first-year college students’ perceptions of peer approval for risky drinking behaviors; and 2) whether associations are moderated by students’ alcohol use status.

Participants:

First-year university students (N = 296) completed an online survey in September, 2014.

Method:

Participants reported their own alcohol use, friends’ alcohol use, perceptions of the typical student’s approval for risky drinking, and ranked 10 types of social media posts in terms of the relative numbers of “likes” received when posted by peers.

Results:

Observed social reinforcement (i.e., “likes”) for peers’ alcohol-related posts predicted perceptions of peer approval for risky drinking behaviors among non-drinking students, but not drinking students.

Conclusions:

For first-year college students who have not yet initiated drinking, observing peers’ alcohol-related posts to receive abundant “likes” may increase perceptions of peer approval for risky drinking.

Heavy drinking on college campuses remains a serious public health problem responsible for more than 500,000 injuries, 600,000 physical assaults, 80,000 sexual assaults, and 2,000 deaths annually.1–3 Because perceptions of peers’ drinking and positive alcohol-related attitudes are among the strongest predictors of college students’ future drinking4,5, but students tend to overestimate these norms6–8, interventions designed to correct misperceived drinking norms have become popular strategies for reducing alcohol-related risks. However, these interventions have led to only modest reductions in students’ drinking6,9–11 and research suggests that popular social networking sites (SNSs) may be to blame. That is, heavy drinking students commonly use SNSs to showcase their drinking12,13, and recent findings suggest that alcohol-related posts inflate observers’ perceptions of how much and how often classmates drink, undermining intervention efforts.12,14–25 For example, one recent experimental study demonstrated that students perceive inflated descriptive drinking norms for typical students at the same university18 after viewing a profile of a fictitious student containing alcohol-related content relative to an alcohol-free version of the same profile. Further, a recent longitudinal study found that self-reported “real life” exposure to alcohol-related content posted by peers on SNSs during the initial 6 weeks of college predicted perceptions of descriptive drinking norms and beliefs about the role of alcohol in the college experience. These alcohol cognitions, in turn, predicted students’ drinking 6 months later.24

Despite research identifying injunctive drinking norms (i.e., perceptions of peer approval for alcohol use), to be uniquely predictive of college students’ future drinking4,6 and negative consequences26,27 potential relationships between these norms and SNS alcohol exposure have not yet received empirical attention25. Meanwhile, several SNSs share behavioral reinforcement features that seem likely to inform injunctive norms. Posts on both Facebook and Instagram, two immensely popular SNSs among college students,28–30 can be socially reinforced, or “liked” by other users. Both SNSs visibly display the number of “likes” garnered by a post immediately below the content. Thus, for college students, whether the “likes” attached to peers’ alcohol related SNS posts inform perceptions of classmates’ approval for drinking behaviors remains an important question. An additional gap in the literature pertains to the characteristics of students whose normative perceptions are most likely to be influenced by what they see on SNS. That is, although injunctive drinking norms are established predictors of future drinking among both alcohol experienced and inexperienced college students, it remains to be seen whether there are differences in the degree to which SNS observations relate to the perceived norms of drinking and non-drinking students.

The current study addresses these unanswered questions by examining 1) whether “likes” variably attached to peers’ alcohol related SNS posts are associated with perceptions of peer approval for risky drinking; and, 2) whether the “likes” garnered by peers’ alcohol-related posts are differentially associated with normative perceptions among students who are already drinking and those who have not yet initiated alcohol use. Consistent with previous social norms research suggesting that peers’ observable drinking behaviors may be more distinctive and highly salient for non-drinking students, relative to those already drinking,27,31 we expected that the relationship between the “likes” garnered by peers’ alcohol-related posts and perceptions of risky drinking approval would be stronger among non-drinking students. To test this hypothesis, students’ alcohol use status (drinker versus non-drinker) is examined as a moderator of the relationship between relative “likes” received by others’ alcohol-related posts and perceptions of approval for risky drinking.

Method

Participants & Procedure

Two-hundred and ninety six first-year students at a private, mid-sized university on the West coast of the United States completed a confidential online survey 25–50 days into their first semester of college. These participants came from control arms of a larger study intervening on parent-child alcohol communication during the transition to college. All of the study’s procedures and measures were approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. Participants consented prior to beginning the confidential survey and were compensated $20 following its completion. The sample had a mean age of 18.10 years (SD =.43) and was 62% female. Fifty-four percent were Caucasian, 22% were Hispanic, 11% were Asian, 9% were African American, and 4% were multi-racial or other. Aside from age (all participants were in their first year), the sample’s demographics closely mirrored those of the University’s entire student body (57% Female, 44% Caucasian, 22% Hispanic, 11% Asian, 6% African American, and 17% multi-racial or other).

Measures

Alcohol Use Status.

Participants were prompted to describe their alcohol use during the past year using one of the following response options: “I have never tried alcohol,” “I am an abstainer (I do not drink at all, but have tried before),” “I am light drinker,” “…moderate drinker,” “…heavy drinker,” or “…problem drinker.” The 36% (n=108) of participants who answered this question with “I have never tried alcohol” or “I am an abstainer” were coded as non-drinkers.

Close College Friends’ Alcohol Use.

A previously published32 3-item scale asked participants to indicate how many of their close college friends drink alcohol, get drunk on a regular basis, and drink primarily to get drunk using response options “None,” “Some,” “Half,” “Most,” or “Nearly All.”32 Internal consistency was high (α =.85) and consistent with scoring procedures outlined by the original authors, responses were summed to create composite scores ranging from 0 (No Friend Alcohol Use) to 12 (High Friend Alcohol Use).

Personal Approval and Injunctive Norms for Drinking.

Parallel sets of 5 items from the expanded Injunctive Norms Questionnaire4,33 assessed participants’ personal approval and perceptions of the approval of a typical same-sex freshman student at their specific university for five risky drinking behaviors: “playing drinking games,” “drinking shots,” “drinking to get drunk,” “drinking alcohol every weekend,” and “drinking under age 21.” Response options ranged from 1 (strongly disapprove) to 7 (strongly approve). Internal consistency was high in both sets of items (α =.91 for own approval; α =.89 for perceived typical student approval) and responses were averaged to create composite scores.

SNS Use Frequency.

Previously published24 items asked participants to indicate the frequency with which they “check” Facebook and Instagram using response options: “Do not have an account,” “Once a month or less,” “2–3 times per month,” “1–3 times per week,” “4–6 times per week,” “1–3 times per day,” “4–6 times per day,” “7 or more times per day.”

Observed “Likes” for Others’ Alcohol-Related Posts.

Because the raw counts of “likes” received by a post on Facebook and Instagram are highly dependent on the network size of the individual posting the content, counts of “likes” attached to alcohol-related posts do not provide meaningful measures of peer reinforcement. More meaningful is how the average number of “likes” received by alcohol-related posts in ones’ newsfeed compares to the average number of “likes” received by other types of frequently encountered posts. To create such a measure, we first conducted a pilot study with 57 undergraduate social media users (all between 18 and 20 years of age) taking part in the psychology department’s human subject pool. Pilot participants were asked to describe the 5 most common topics of text and photographic posts they encounter on Facebook and Instagram SNSs. While there was some variability in the types of posts described, 10 distinct types of posts were described by large numbers of students. Participants in the current study were presented lists of these 10 post types in randomized order. Parallel items asked participants to rank the post types in terms of the average numbers of “likes” they receive, relative to one another, in their own 1) Facebook newsfeed and, 2) Instagram newsfeed, from “least likes” (0) to “most likes”(9). Participants were encouraged to check their Facebook and Instagram feeds for reference while ranking the post types. To improve distributions, raw ranks for alcohol-related posts were grouped in pairs and recoded from 0 (least likes) to 4 (most likes). Of interest to the current investigation were the “likes” rank of posts related to, “Alcohol, getting drunk, and being hung over” relative to the other types of posts.

Results

Drinkers significantly exceeded non-drinkers in the proportions having Facebook and Instagram accounts, as well as frequencies of checking Facebook and Instagram (Table 1). Relative to non-drinking students, drinkers also ranked the “likes” received by others’ alcohol-related posts significantly higher on both Facebook and Instagram, reported greater personal approval for risky drinking behaviors, and having college friends with significantly higher levels of alcohol use. Notably, however, perceptions of typical student approval for risky drinking did not statistically differ between drinkers and non-drinkers, t (295) =1.52, p=.13.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for SNS Use Frequency, “Likes” For Alcohol-Related Posts, and Approval for Underage Drinking by Drinker Status

| Overalla (n=296) | Non-Drinkersb (n=108) | Drinkersb (n=188) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FB | IG | FB | IG | FB | IG | |

| SNS Use Frequencies % (N) | ||||||

| No account | 9.1 (27)** | 21.5 (64) | 14.8 (16)** | 32.4 (35)** | 5.8 (11)* | 15.3(29)* |

| Less than once a day | 26.9 (80)** | 12.4 (37) | 27.8 (30) | 13.8 (15) | 26.5 (50) | 11.6 (22) |

| 1–3 times per day | 31.6 (94)** | 21.9 (65) | 26.9 (29) | 20.4 (22) | 34.4 (65)** | 22.8 (43) |

| 4–6 times per day | 16.8 (50) | 21.9 (65)* | 18.5 (20) | 16.7 (18) | 15.9 (30) | 24.9 (47)*** |

| 7+ times per day | 15.5 (46) | 22.2 (66)** | 12.0 (13) | 16.7 (18) | 17.5 (33)** | 25.4 (48)*** |

|

Alcohol-Related “Likes” M(SD) (0=least likes; 4=most likes) |

1.96 (1.03) | 1.84 (1.29) | 1.73 (1.05) | 1.47 (1.31) | 2.10 (.99)*** | 2.04 (1.24)*** |

| Overall | Non-Drinkersb | Drinkersb | ||||

|

College Friends’ Alcohol Use (0=none use; 12=all use) |

4.98 (3.26) | 3.17 (2.59)*** | 6.02 (3.15)*** | |||

|

Own Approval M(SD) (1=low-7=high) |

4.40 (1.75) | 3.23 (1.41)*** | 5.08 (1.58)*** | |||

|

Perceived Typical Freshman Approval

M(SD) (1=low-7=high) |

5.33 (1.34) | 5.17 (1.28) | 5.42 (1.37) | |||

Significant differences overall between Facebook and Instagram, as indicated by Students’ T and Chi-Square tests, are indicated by asterisks in the overall columns in the top half of the table;

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Significant differences between non-drinkers and drinkers are denoted by asterisks in the non-drinker and drinker columns in both the top and bottom halves of the table.

Having established that the majority of participants in the sample used both SNSs, corresponding Facebook and Instagram specific variables were correlated with each other, and similarly correlated with all other study variables (Table 2), Facebook and Instagram specific variables were combined into composite frequency of use and alcohol-related “likes” ranking variables in order to avoid multi-collinearity in multivariate analyses. Composite measures were computed by summing SNS-specific frequency of use (i.e., Facebook + Instagram) and ranks for alcohol-related “likes” (i.e., rank on Facebook + rank on Instagram). As presented in Table 3, a hierarchical regression model tested whether the relative “likes” received by peers’ alcohol–related posts on the SNSs, and/or the interaction between relative “likes” and alcohol use status would predict perceptions of typical student approval for risky drinking after controlling for one’s sex, frequency of using the SNSs, own approval for risky drinking, and close friends’ drinking behavior. Examination of coefficients indicated that there was no significant main effect for alcohol-related “likes” on perceptions of typical student approval for underage drinking. However, the coefficients for drinker-status and the interaction term were both significant.

Table 2.

Bivariate Correlations among non-drinkers (above diagonal) and drinkers (below diagonal)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | FB Use Frequency | - | .294** | .762*** | .523*** | .294** | .480*** | .113 | .139 | .285** |

| 2 | IG Use Frequency | .291*** | - | .843*** | .327*** | .769*** | .673*** | .228* | .101 | .342*** |

| 3 | FB + IG Use Frequency | .758*** | .844*** | - | .516*** | .687*** | .726*** | .091 | .147 | .392*** |

| 4 | FB Likes Alc Posts | .338*** | .148* | .287*** | - | .381*** | .780*** | .079 | .007 | .323** |

| 5 | IG Likes Alc Posts | .138 | .610*** | .492** | .381*** | - | .871*** | .315** | .001 | .325** |

| 6 | FB+IG Likes Alc Posts | .262*** | .464*** | .463** | .784*** | .848*** | - | .220* | .001 | .387*** |

| 7 | College Friends’ Alcohol Use | .081 | .169* | .161* | .151* | .159* | .191* | - | .141 | .313** |

| 8 | Own Approval | .060 | .145* | .133 | .108* | .169* | .192* | .564*** | - | .290** |

| 9 | Typ Freshman Approval | .067 | .113 | .115 | .033 | .077 | .071 | .322*** | .618*** | - |

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Regression results for centered variables predicting perceptions of typical student drinking approval

| Step | Variables | β | R2 | R2Δ | FΔ | df |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Covariates | .254 | .254*** | 24.81*** | 4, 292 | |

| Sex Female | −.015 | |||||

| Own Alcohol Approval | .419*** | |||||

| College Friends’ Alcohol Use | .063 | |||||

| SNS Use Frequency | .129* | |||||

| 2 | Main Effects | .301 | .048*** | 9.87*** | 2, 290 | |

| SNS Likes for Others Alc-Related Posts | .04 | |||||

| Alcohol Use-Status | −.260*** | |||||

| 3 | Two-Way Interaction | .329 | .028** | 11.78** | 1, 289 | |

| SNS Likes*Alcohol Use-Status | −.449*** |

Note. β reflects values at the step the predictor was first entered

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001.

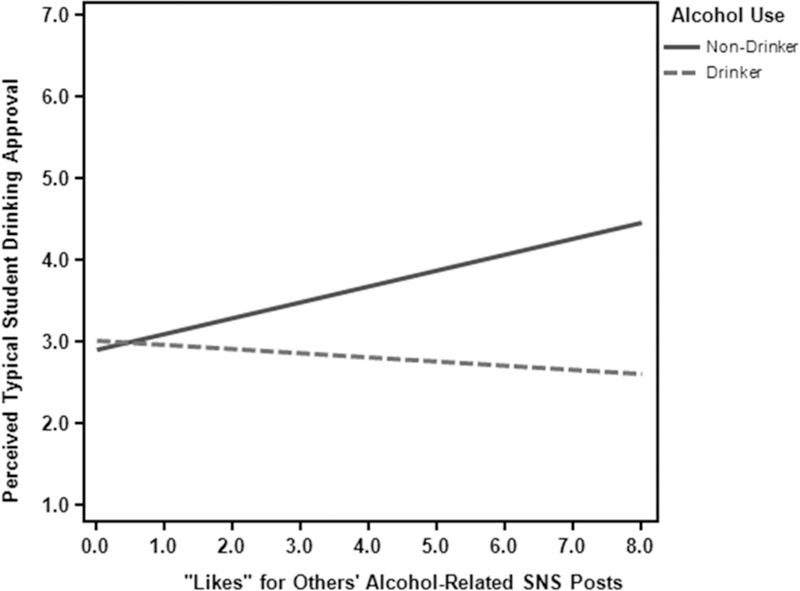

To interpret the interaction, perceptions of typical student approval for underage drinking were plotted as a function of relative “likes” for others’ alcohol related SNS content separately for drinkers and non-drinkers (see Figure 1) and were accompanied by tests of simple slopes.34 Only the line for non-drinkers differed significantly from zero, (B = .20, SE = .06), t (289) = 3.04, p = .002) confirming that relative “likes” received by others’ alcohol-related SNS posts positively predicted perceptions of peers’ approval of risky drinking only among alcohol inexperienced first year students.

Figure 1.

Non-drinkers’ and drinkers’ perceptions of typical student approval for underage drinking as a function of relative “likes” received by others’ alcohol-related SNS posts.

Comment

Among non-drinking students, as social reinforcement (i.e., “likes”) garnered by peers’ alcohol-related SNS posts increased so did their perceptions of peer approval for risky drinking behaviors. This finding suggests that those who lack ample first-hand experience observing alcohol-use among close friends, may rely on SNSs, specifically the “likes” attached to peers’ alcohol-related posts, to estimate classmates’ approval for risky drinking. While both drinkers and non-drinkers perceived similar levels of peer approval for risky drinking, drinkers’ normative perceptions were not related to “likes.” Rather, drinkers’ estimations of approval appeared to be more related to their own approval and alcohol use of their close college friends. Results suggest that while observations in face-to-face drinking contexts are likely to inform the injunctive norms for risky drinking among alcohol experienced students, students in non-drinking social circles may glean normative information about peer approval for risky drinking from the behaviors they see extended network peers’ partake in and socially reinforce on SNSs.

Implications

Given that injunctive drinking norms are potent predictors of future drinking and negative consequences among college students, the relationship between non-drinkers’ observations of “likes” for others’ alcohol-related SNS posts and perceptions of approval for risky drinking may carry important implications for prevention efforts aimed at delaying alcohol initiation among emerging adults. As suggested by the relatively low alcohol use by close friends of non-drinkers, prevention efforts might aim to reinforce or enhance the salience of injunctive drinking norms within non-drinking students’ close peer groups in order to mitigate potential risks associated with “liked” alcohol content of distal peers. Strategic interventionists might also aim to adjust students’ normative perceptions through innovative SMS campaigns aimed to decrease the “likes” attached to students’ alcohol-related content and increase “likes” attached to non-alcohol-related content. Finally, emerging social norms interventions that innovatively integrate with Facebook to more believably and interactively correct normative perceptions35 and/or deliver normative feedback35,36 might prove especially effective among alcohol inexperienced students and other groups of students for whom social media observations and normative perceptions are correlated.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

First, the “likes” ranking assessment was used for the first time in this study. Rather than relying on numeric responses (i.e., actual numbers of “likes”) for the various post-types, which are likely to be dependent on the size of the posting individual’s network, the assessment required participants to rank ten common post types in terms of numbers of “likes” received in their Facebook and Instagram newsfeeds, which provided a straight-forward measure of post popularity. However, although instructions recommended that students consult their SNS newsfeeds when ranking the post types, it is unclear whether participants followed this recommendation. Second, this study’s sample consisted of fewer than 300 participants from a single university. Future studies should employ larger cohorts of students from multiple universities. Third, due to the cross-sectional design, directionality of relationships between SNS “likes” and perceptions of injunctive norms for alcohol use could not be assessed. Prospective research which assesses perceived injunctive norms and drinking behaviors at multiple times during students’ first-year, and more objectively assesses “likes” received by peers’ alcohol-related posts, could better elucidate the degree to which “likes” attached to peers’ alcohol-related SNS posts influence perceptions and subsequent risky drinking behavior.

Conclusion

This study directs empirical attention to the “like” mechanism in several popular SNSs. After controlling for first-year students’ own alcohol-related attitudes and close friends’ drinking behaviors, observed “likes” garnered by peers’ alcohol-related Facebook and Instagram posts were associated with perceptions of peer approval for risky drinking behaviors among nondrinking students, but were unrelated to perceptions of approval among alcohol experienced students. These findings are the first to suggest that underage college students who lack ample first-hand experience observing alcohol-use among close friends, may rely on SNSs, specifically the “Likes” attached to peers’ alcohol-related posts, to estimate injunctive drinking norms.

References

- 1.Foster C, Caravelis C, Kopak A. National college health assessment measuring negative alcohol-related consequences among college students. American Journal of Public Health Research 2014;2(1):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among US college students ages 18–24, 1998–2005. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs, Supplement 2009(16):12–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alcoholism NIoAAa. College drinking 2015; http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/CollegeFactSheet/CollegeFact.htm. Accessed December 11, 2014.

- 4.Larimer ME, Turner AP, Mallett KA, Geisner IM. Predicting drinking behavior and alcohol-related problems among fraternity and sorority members: Examining the role of descriptive and injunctive norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 2004;18(3):203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neighbors C, Lee CM, Lewis MA, Fossos N, Larimer ME. Are social norms the best predictor of outcomes among heavy-drinking college students? Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 2007;68(4):556–565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Borsari B, Carey KB. Descriptive and injunctive norms in college drinking: A meta-analytic integration. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 2003;64(3):331–341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Gender-specific misperceptions of college student drinking norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 2004;18(4):334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Perkins H The Social Norms Approach to Preventing School and College Age Substance Abuse: A Handbook for Educators, Counselors, and Clinicians Jossey-Bass; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeJong W, Schneider SK, Towvim LG, et al. A multisite randomized trial of social norms marketing campaigns to reduce college student drinking. Journal of Studies on Alcohol 2006;67(6):868–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Huh D, Mun EY, Larimer ME, et al. Brief motivational interventions for college student drinking may not be as powerful as we think: An individual participant‐level data meta‐analysis. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research 2015;39(5):919–931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewis MA, Neighbors C. Social norms approaches using descriptive drinking norms education: A review of the research on personalized normative feedback. Journal of American College Health 2006;54(4):213–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ridout B, Campbell A, Ellis L. ‘Off your Face (book)’: Alcohol in online social identity construction and its relation to problem drinking in university students. Drug and Alcohol Review 2012;31(1):20–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hebden R, Lyons AC, Goodwin I, McCreanor T. “When you add alcohol, it gets that much better:” University students, alcohol consumption, and online drinking cultures. Journal of Drug Issues 2015;45(2):214–226. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beullens K, Schepers A. Display of alcohol use on Facebook: A content analysis. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2013;16(7):497–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dolcini MM. A new window into adolescents’ worlds: The impact of online social interaction on risk behavior. Journal of Adolescent Health 2014;54(5):497–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Egan KG, Moreno MA. Alcohol references on undergraduate males’ Facebook profiles. American Journal of Men’s Health 2011;5(5):413–420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fournier AK, Clarke SW. Do college students use Facebook to communicate about alcohol? An analysis of student profile pages. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace 2011;5(2). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fournier AK, Hall E, Ricke P, Storey B. Alcohol and the social network: Online social networking sites and college students’ perceived drinking norms. Psychology of Popular Media Culture 2013;2(2):86–95. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreno MA, Christakis DA, Egan KG, Brockman LN, Becker T. Associations between displayed alcohol references on Facebook and problem drinking among college students. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine 2012;166(2):157–163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moreno MA, Kota R, Schoohs S, Whitehill JM. The Facebook influence model: A concept mapping approach. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 2013;16(7):504–511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moreno MA, D’Angelo J, Kacvinsky LE, Kerr B, Zhang C, Eickhoff J. Emergence and predictors of alcohol reference displays on Facebook during the first year of college. Computers in Human Behavior 2014;30:87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Morgan EM, Snelson C, Elison-Bowers P. Image and video disclosure of substance use on social media websites. Computers in Human Behavior 2010;26(6):1405–1411. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Westgate EC, Neighbors C, Heppner H, Jahn S, Lindgren KP. “I will take a shot for every ‘like’ I get on this status”: Posting alcohol-related Facebook content is linked to drinking outcomes. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 2014;75(3):390–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boyle SC, LaBrie JW, Froidevaux NM, Witkovic YD. Different digital paths to the keg? How exposure to peers’ alcohol-related social media content influences drinking among male and female first-year college students. Addictive Behaviors 2016;57:21–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Steers M- LN, Moreno MA, Neighbors C. The influence of social media on addictive behaviors in college students. Current Addiction Reports 2016;3(4):343–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.LaBrie JW, Hummer JF, Neighbors C, Larimer ME. Whose opinion matters? The relationship between injunctive norms and alcohol consequences in college students. Addictive Behaviors 2010;35(4):343–349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lewis MA, Neighbors C, Geisner IM, Lee CM, Kilmer JR, Atkins DC. Examining the associations among severity of injunctive drinking norms, alcohol consumption, and alcohol-related negative consequences: The moderating roles of alcohol consumption and identity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 2010;24(2):177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cupid JA, Wallace SL. Social Branding of College Students to Seek Employment. In: Langmia K, Tyree T, O’Brien P, Sturgis I, eds. Social Media: Pedagogy and Practice: University Press of America; 2013:155–171. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Salomon D Moving on from Facebook: Using Instagram to connect with undergraduates and engage in teaching and learning. College & Research Libraries News 2013;74(8):408–412. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lenhart A, Duggan M, Perrin A, Stepler R, Rainie H, Parker K. Teens, Social Media & Technology Overview 2015. Pew Research Center [Internet & American Life Project]; 2015.

- 31.Carey KB, Borsari B, Carey MP, Maisto SA. Patterns and importance of self-other differences in college drinking norms. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 2006;20(4):385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abar C, Turrisi R. How important are parents during the college years? A longitudinal perspective of indirect influences parents yield on their college teens’ alcohol use. Addictive Behaviors 2008;33(10):1360–1368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baer JS. Effects of college residence on perceived norms for alcohol consumption: An examination of the first year in college. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors 1994;8(1):43. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting regressions London: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Boyle SC, Earle AM, LaBrie JW, Smith DJ. PNF 2.0? Initial evidence that gamification can increase the efficacy of brief, web-based personalized normative feedback alcohol interventions. Addictive Behaviors 2017;67:8–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ridout B, Campbell A. Using Facebook to deliver a social norm intervention to reduce problem drinking at university. Drug and Alcohol Review 2014;33(6):667–673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]