EUS-guided drainage of pancreatic fluid collection (PFC) is currently the accepted standard of care, primarily because of the associated ease, safety, and efficiency of the procedure. Procedure-related bleeding reportedly occurs in 1% to 2% of cases during EUS-guided drainage of PFC. This bleeding can be effectively managed with the deployment of a metal stent.1 We present a case of significant bleeding that occurred during EUS-guided drainage of walled-off necrosis (WON) that was successfully managed with a dedicated large-caliber self-expandable metal stent (LCMS).

A 35-year-old man, who had received a diagnosis of acute necrotizing pancreatitis 7 weeks earlier, presented with abdominal pain and fever for the previous 2 weeks. On evaluation, laboratory test results showed mild anemia (hemoglobin, 12.6 g/dL; leukocytosis, 13,400 white blood cells/μL, elevated serum amylase [386 IU/L], and elevated lipase [288 IU/L] [>3 upper limit of normal]). Contrast-enhanced CT and EUS showed WON (78 × 74 mm) with minimal debris seen in the lesser sac (Figure 1, Figure 2). The subject was scheduled for EUS-guided drainage with a plastic stent by the use of a standard therapeutic echo endoscope (UCT-180; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). The standard steps of EUS-guided drainage were followed. With careful avoidance of any interposing vessel on EUS, the wall of the WON was punctured with a 19-gauge regular FNA needle, after which mild echogenic turbulence was observed emanating from the puncture site. The turbulence became slightly more obvious and intense after the passage of the guidewire (0.035 guidewire, 450 cm, Jagwire; Boston Scientific, Natick, Mass, USA) into the PFC, suggesting active bleeding inside the cavity (Fig. 3). The track was dilated with a coaxial over-the-guidewire cystotome (6F; Endo-flex GmbH, Dusseldorf, Germany), after which the bleeding became more pronounced and the Doppler appearance was that of “fire-breathing” (Fig. 4). At this juncture, it was decided to switch to placement of an LCMS (instead of a plastic stent) for providing tamponade. The track was quickly dilated with a small-caliber balloon (6 mm, Titan balloon; Cook Medical, Bloomington, Ind, USA) and kept in situ for a minute, which reduced the bleeding, reinforcing our decision to use an LCMS. A biflanged self-expandable metal stent (16 × 20 mm; Nagi Taewoong Medical, Gyenoggi-do, Korea) was deployed, which immediately stopped the bleeding because of external compression at the puncture site from stent expansion (Video 1, available online at www.VideoGIE.org). Endoscopy showed the metal stent in place with no active oozing from the puncture site beside the stent and a small amount of fresh blood draining into the stomach from inside the WON (Fig. 5). An additional double-pigtail stent was placed through the LCMS to prevent any clogging from clots within the WON.

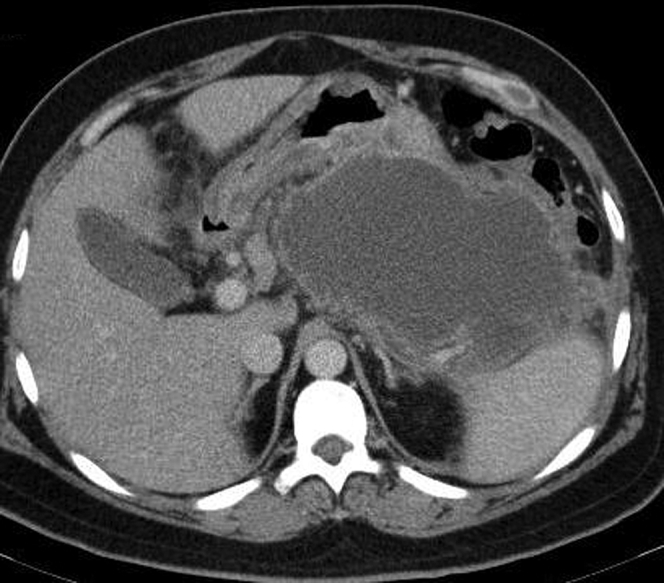

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced CT view showing large walled-off necrosis almost replacing body and tail of pancreas.

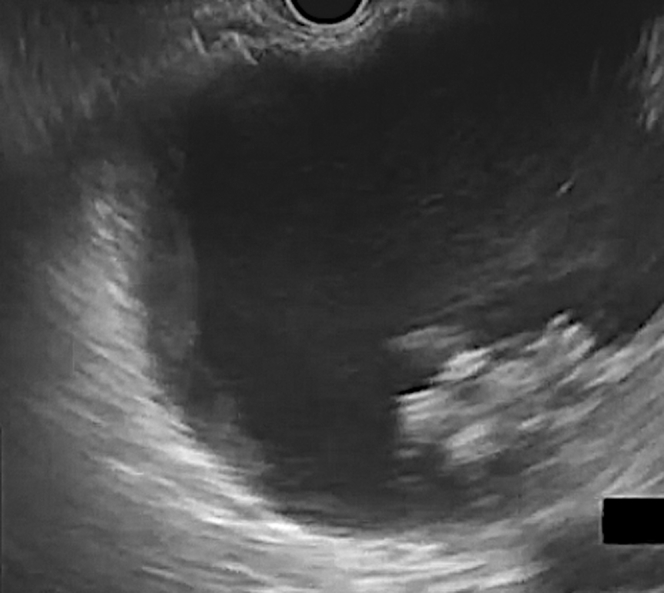

Figure 2.

EUS view of walled-off necrosis with little debris.

Figure 3.

After puncture with regular FNA needle, echogenic jet entering into the cavity from puncture site suggests bleeding.

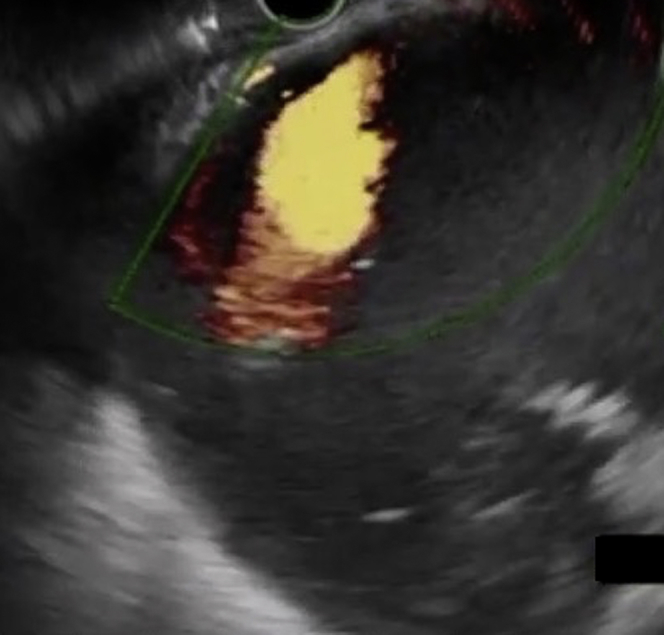

Figure 4.

Doppler US view showing mega jet after cystotome insertion, producing “fire-breathing” appearance.

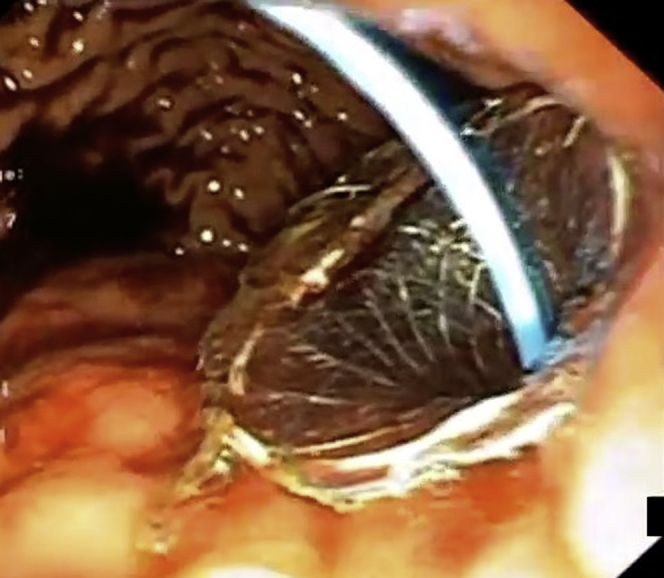

Figure 5.

Endoscopic view showing plastic stent within metal stent, with no active oozing and minimal fresh blood in stomach.

After the procedure, the patient remained in hemodynamically stable condition, received standard care and antibiotics, and had no drop in hemoglobin during a 3-day hospital stay. After 3 days, US of the abdomen showed significant decrease in WON size. Bleeding during EUS-guided drainage of WON can be effectively managed with the placement of an LCMS.

Disclosure

All authors disclosed no financial relationships relevant to this publication.

Supplementary data

Video shows entry-site bleeding during UES-guided drainage of walled-off necrosis and its management.

Reference

- 1.Saftoiu A., Ciobanu L., Seicean A. Arterial bleeding during EUS-guided pseudocyst drainage stopped by placement of a covered self-expandable metal stent. BMC Gastroenterol. 2013;13:93. doi: 10.1186/1471-230X-13-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Video shows entry-site bleeding during UES-guided drainage of walled-off necrosis and its management.