FACE pACP decreased HIV-specific symptoms among adolescents through a pathway of increasing families’ understanding of their adolescents’ end-of-life treatment preferences.

Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To determine the effect of family-centered pediatric advance care planning (FACE pACP) on HIV-specific symptoms.

METHODS:

In this single-blinded, randomized controlled trial conducted at 6 US hospital-based HIV clinics, 105 adolescent-family dyads, randomly assigned from July 2011 to June 2014, received 3 weekly sessions in either the FACE pACP arm ([1] pediatric advance care planning survey, [2] Respecting Choices interview, and [3] 5 Wishes directive) or the control arm ([1] developmental history, [2] safety tips, and [3] nutrition and exercise tips). The General Health Assessment for Children measured patient-reported HIV-specific symptoms. Latent class analyses clustered individual patients based on symptom patterns. Path analysis examined the mediating role of dyadic treatment congruence with respect to the intervention effect on symptom patterns.

RESULTS:

Patients were a mean age of 17.8 years old, 54% male, and 93% African American. Latent class analysis identified 2 latent HIV-symptom classes at 12 months: higher symptoms and suffering (27%) and lower symptoms and suffering (73%). FACE pACP had a positive effect on dyadic treatment congruence (β = .65; 95% CI: 0.04 to 1.28), and higher treatment congruence had a negative effect on symptoms and suffering (β = −1.14; 95% CI: −2.55 to −0.24). Therefore, FACE pACP decreased the likelihood of symptoms and suffering through better dyadic treatment congruence (β = −.69; 95% CI: −2.14 to −0.006). Higher religiousness (β = 2.19; 95% CI: 0.22 to 4.70) predicted symptoms and suffering.

CONCLUSIONS:

FACE pACP increased and maintained agreement about goals of care longitudinally, which lowered adolescents’ physical symptoms and suffering, suggesting that early pACP is worthwhile.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Evidence supports the feasibility, acceptability, and initial efficacy of the family-centered pediatric advance care planning intervention for increasing congruence in end-of-life treatment preferences in adolescents with HIV and their families in a small randomized clinical trial.

What This Study Adds:

Families' understanding of their adolescent's treatment preferences increased classification in the lower HIV symptoms group 12 months postintervention. Lack of understanding predicted more HIV symptoms. FACE pACP families had 3 times the odds of understanding their adolescents’ treatment preferences, compared with controls.

Despite medical advances, adolescents living with HIV or AIDS still have mortality rates 6 to 12 times greater than the general US population.1–3 Globally, AIDS is the second leading cause of adolescent deaths and the leading cause of adolescent deaths in Africa.4 HIV is a serious illness (with risk of morbidity and mortality) for which pediatric advance care planning (pACP) is appropriate.

In pACP, providers aim to relieve the suffering of children living with serious illness at any stage of disease5,6 by supporting family engagement in understanding their child’s goals for care, by communicating goals of care and end-of-life treatment preferences to the physician, and by documenting treatment preferences (similar to adult advance care planning [ACP]).5,6 Family-centered pediatric advance care planning (FACE pACP)7–10 is used to engage adolescents and families in the first 2 steps of the 3-step Respecting Choices model11: (1) identifying a surrogate decision-maker (for those who are ≥18 years or age), heretofore referred to as family; and (2) engaging in goals-of-care conversations with their families to create advance care plans.

The FACE pACP protocol is grounded in transactional stress and coping theory, whereby problem solving12 provides some control in low-control situations.13 Evidence supports the effects of problem-focused coping on survival among adult patients with cancer.14–16 Perceived control is associated with decreased pain17 and buffered mortality risk.18 Social support is associated with HIV-related symptom reduction19 and decreased mortality risk.20 Transactional stress and coping theory also indicates that religious coping influences symptoms in complex ways.21 Religious struggle is associated with poor health outcomes,22 whereas positive religious coping is associated with improved health outcomes in adults with HIV.23,24 Threat appraisal is related to coping and reappraisal. Our pilot study findings25 and research with children of divorce and bereaved children26,27 suggest that one form of threat appraisal (loss of others or objects) significantly influences symptoms.

Session 2 of the FACE pACP intervention also builds on the representational approach to patient education.28 Intervention trials reveal improved symptom management and decreased cancer pain in adults.29–31

In this trial, we tested a full theoretical model of pACP. The primary outcome was to reduce HIV-specific symptoms and suffering. We hypothesized that compared with an active control, (1) FACE pACP would maintain congruence in end-of-life treatment preferences (ie, the family would know what the adolescent would want) 1 year postintervention, and (2) higher treatment congruence would mediate lower HIV-specific symptoms and suffering by increasing control for adolescents’ coping through making choices, through problem solving, and through patient representation of illness (eg, adolescents’ understanding of current and past symptoms) and by strengthening family support (communication about treatment preferences). We further hypothesized that higher religiousness would limit the benefits of higher congruence on symptoms and that loss of others or objects would indirectly increase symptoms.

Methods

Design

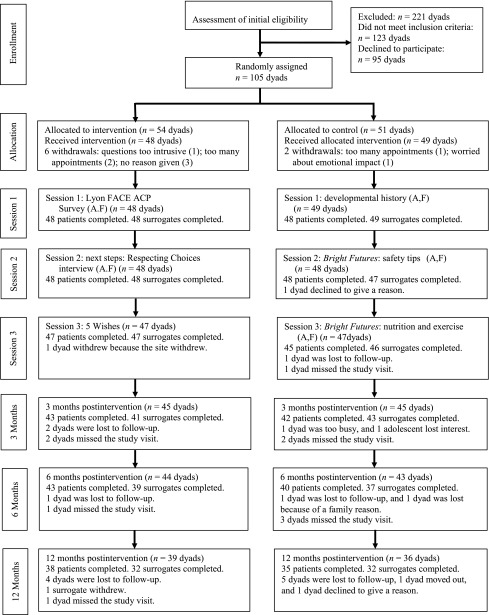

FACE pACP was a 2-parallel group, single-blinded, randomized controlled clinical trial with an intent-to-treat design (Fig 1). Adolescents and their families independently completed questionnaires at 3, 6, 12, and 18 months postintervention administered by research assistants (RAs) who were blinded to randomization. The sample size of the 18-month follow-up was not large enough to conduct a latent class analysis (LCA); thus, in the present analysis, we evaluated outcomes through 12 months postintervention. The institutional review board at each site approved the protocol. Participants provided written informed consent or assent and were compensated.

FIGURE 1.

Consort diagram: FACE pACP trial. A, adolescent; F, family.

Setting and Participants

Adolescents ages 14 to 21 years old with HIV or AIDS and legal guardians (for minors) or chosen surrogate decision-makers who were at least 18 years old were enrolled in FACE pACP. Adolescent-family dyads were recruited between July 2011 and June 2014 from 6 pediatric and/or adolescent, hospital-based HIV clinics: Children’s National, Johns Hopkins University, and Howard University (n = 32); St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital (n = 19); University of Miami Miller School of Medicine (n = 26); and Children’s Diagnostic and Treatment Center (n = 28). Inclusion criteria included a knowledge of the diagnosis and the ability to speak and understand English. Exclusion criteria for all participants included being a ward of the state; having known cognitive delay; being identified on secondary screening as severely depressed,32 suicidal,32 homicidal,33 or psychotic33; and being positive for HIV dementia.34 Further study details are published elsewhere.35,36

Randomization and Interventions

After the completion of baseline assessments, dyads were randomly assigned by the coordinating center to either the FACE pACP arm or the control arm using a computerized, 1:1 randomly permuted block design. Randomization was blocked by study site and mode of HIV transmission. Study coordinators were notified of randomization, and weekly intervention or control sessions 1 to 3 were scheduled. Sessions were facilitated by using a structured guide. Session 2 was videotaped and/or audiotaped and reviewed for fidelity.

Intervention: FACE pACP

Intervention dyads received usual care, an ACP booklet, and FACE pACP. Sessions were conducted by trained and/or certified RA interventionists (either clinicians or graduate students in nursing, psychology, counseling, and public health). Three 60-minute sessions were conducted ∼1 week apart (see Table 1 for details; session 1, ACP survey37–39; session 2, Respecting Choices ACP Next Steps facilitated interview and statement of treatment preferences [SoTP]11; and session 3, 5 Wishes directive40). For adolescents <18 years of age, their legal guardian’s signature was required on the 5 Wishes directive. A copy was given to the family.

TABLE 1.

FACE pACP Intervention

| Session Foundation | Session Goals | Session Process | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Session 1 | Lyon FACE ACP survey: adolescent and surrogate versions to set stage for EOL conversations | (1) To assess the adolescent’s values, spiritual and other beliefs, and life experiences with illness and EOL care and (2) to assess when to initiate ACP. | (1) Orient family to study and issues, (2) survey adolescent privately, and (3) survey surrogate privately with regard to what the surrogate believes the adolescent prefers. |

| Session 2 | Next steps: ACP Respecting Choices interview (Hammes and Briggs11) | (1) To facilitate conversations and share decision-making between the adolescent and surrogate about palliative care, providing an opportunity to express fears, values, spiritual and other beliefs, and goals with regard to death and dying; and (2) to prepare the guardian or surrogate to be able to fully represent the adolescent’s wishes. | In stage 1, the teenager’s understanding of the condition is assessed. In stage 2, the teenager’s philosophy about EOL decision-making is explored. In stage 3, the rationale for future decisions the teenager would want the surrogate to act on is reviewed. In stage 4, the SoTP is used to describe scenarios and choices. In stage 5, the need for future conversations is summarized, and referrals are made. |

| Session 3 | The 5 Wishes directive is a legal document that is used to help a person express how he or she wants to be treated if seriously ill and unable to speak for himself or herself. Unique among living will and health agent forms, all of a person’s needs are addressed in it: medical, personal, emotional, and spiritual. | (1) Which person the teenager wants to make health care decisions for him or her, (2) the kind of medical treatment the teenager wants, (3) how comfortable the teenager wants to be, (4) how the teenager wants people to treat him or her, (5) what the teenager wants loved ones to know, and (6) any spiritual or religious concerns the teenager may have. | For adolescents <18 years of age, the 5 Wishes directive must be signed by their legal guardian. Processes, such as labeling feelings and concerns as well as finding solutions to any identified problem, are facilitated (with appropriate referrals). These sessions may include other family members or loved ones. |

National Cancer Institute; National Institutes of Health. Research-tested intervention programs (RTIPs). Available at: https://rtips.cancer.gov/rtips/programDetails.do?programId=17054015. Accessed June 5, 2018. EOL, end-of-life.

RA interventionists e-mailed the treating physician a summary of the goals-of-care conversation, a copy of the SoTP, and the signed 5 Wishes directive. Documents were entered into the medical record per institutional practices.

Active Control

Dyads who were randomly assigned to the control arm received usual care, an ACP booklet, and the control condition (session 1, developmental history: adolescent developmental history was taken41 separately, and medical questions were removed to prevent risk of contamination; session 2, safety tips: the RA for the control arm provided counseling on safety information to the dyad using Bright Futures guides42; session 3, nutrition and exercise: the RA for the control arm provided counseling on exercise and nutrition to the dyad using Bright Futures guides42).

Primary Outcome Measure

The Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group General Health Assessment for Children 43,44 HIV-related symptom subscale was used. On a 6-point Likert scale, adolescents rated the degree of distress experienced with 17 HIV-related physical symptoms. For analysis, each symptom was dichotomized (0: not at all; 1: at least some). Higher scores reflected more symptoms.

Secondary Outcome Measures

The Brief Multidimensional Measurement of Religiousness/Spirituality (adapted) was developed to assess health-relevant domains of religiousness and/or spirituality. Reliability and validity is well established with adolescents.45–48 On the basis of our previous research, the following 5 items were preselected on the basis of correlations with social, emotional, and school quality of life48: “I feel God’s presence”; “How often do you pray privately?”; “How often do you go to religious services?”; “To what extent do you consider yourself a religious person?”; and “To what extent do you consider yourself a spiritual person?” In a previous analysis, 2 latent classes for religiousness in the same sample were identified: a higher religiousness and/or spirituality group (70% of dyads) and a lower religiousness and/or spirituality group (30%) for adolescents.48 This latent class variable was used in modeling for this study.

The Threat Appraisal Scale27 reliability and validity is well established among adolescents.26,27 On the basis of our pilot data,25 only the loss of desired others or objects subscale was examined. Items on the subscale included the following: “When you learned you were HIV-positive, you thought that you might…not get to do something that you wanted to do,” “…not get to spend time with someone you like,” “…not go somewhere that you wanted to go,” and “…have to give up things you own.” Responses were on a 5-point Likert scale. We hypothesized that loss of desired others or objects at baseline would mediate the effect of FACE pACP on symptom and suffering classification.

The Medication Adherence Self Report Inventory49 is a self-report measure of antiretroviral medication adherence and indicates the estimated percentage of time adolescents took their HIV medications in the last month. This visual analog scale has excellent validity.49

An SoTP11 was used to explore and document specific treatment preferences of the adolescent and obtain the families’ understanding of the adolescents’ goals. Three poor outcome situations included the following: “long hospitalization with many procedures and low chance of survival,” “never be able to walk or talk again and would need 24-hour nursing care,” and “never knowing who you are or who you are with and would need 24-hour nursing care.” Choices included the following: “to continue all treatment so I could live as long as possible” (“Staying alive is most important to me no matter what”), “to stop all efforts to keep me alive” (“My definition of living well is more important than length of life”), or, “unsure.” FACE pACP dyads discussed the SoTP together in session 2, whereas control dyads completed it individually after session 2.

Statistical Analysis: Congruence

A longitudinal latent class analysis (LLCA) was applied to analyze the longitudinal pattern of adolescent-family congruence on treatment preferences in the 3 HIV-related situations over time. Congruence on treatment preferences between adolescents and families in the 3 situations (measured at session 2 and at 6 and 12 months postintervention) was used as the outcome indicator in LLCA. The latent class variable was saved as an observed categorical variable for analysis.

Statistical Analysis: Symptoms

Instead of using the 17 self-reported HIV-specific symptoms as outcome variables in our analytical model, the LCA50 was applied as a data reduction tool to generate a categorical latent variable reflecting the pattern of the HIV-specific symptoms at 12 months postintervention. The latent class variable was used as a categorical outcome in the path model. The sample size for the path analysis was estimated on the basis of assumptions for structural equation modeling (at least 5 observations per variable).51,52 With only 11 variables in our model, the minimum sample size needed was n = 66. Our 12-month sample size was n = 73. In the path analysis model, the dyadic congruence latent profile variable was treated as a mediating factor through which the intervention indirectly influenced the pattern of HIV-specific symptoms. The religiousness and/or spirituality profile was treated as a moderating factor. A Bayesian estimator was applied for modeling to overcome small sample size shortcomings of the maximum likelihood estimator.51 All the models were implemented by using Mplus 7.4.53

Results

Sample Description

Of those initially eligible and enrolled, 108 adolescent-family dyads completed a secondary screening (Fig 1). Of these, 1 adolescent reported homicidal ideation, and 2 dyads withdrew without reasons, resulting in 105 randomly assigned dyads. Retention rates were 83% (87 of 105) and 71% (75 of 105) for 6- and 12-month follow-ups, respectively. Nine cases were unblinded. No significant baseline differences existed in symptoms by study arm. No adverse events were reported.54

Adolescents were a mean age of 18 years old (range: 14–21 years old), 54% male, 93% African American, and 55% of adolescents had viral suppression (Table 2). Family participants were a mean age of 45 years old (range: 20–77 years old), 82% female, and 90% African American. One-third of families reported they were HIV-positive; 62% had a high school education or less, and half lived in households with incomes below the federal poverty level.

TABLE 2.

Baseline Characteristics for 105 Randomly Assigned Intervention and Control Adolescents

| Characteristic | Intervention, n = 54 | Control, n = 51 | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | |||

| Mean (SD) | 17.9 (1.88) | 17.7 (1.99) | — |

| Range | 14.0–20.0 | 14.0–20.0 | .63a |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 29 (53.7) | 26 (51.0) | — |

| Female | 25 (43.3) | 25 (49.0) | .85b |

| Race and/or ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| African American | 50 (92.6) | 48 (94.1) | — |

| Hispanic non–African American | 4 (7.4) | 3 (5.9) | .99b |

| Mode of HIV transmission, n (%) | |||

| Perinatal infection | 41 (75.9) | 37 (72.6) | — |

| Nonperinatal infection | 13 (24.1) | 14 (27.5) | .82b |

| Self-reported sexual orientation, n (%) | |||

| Nonheterosexual | 19 (35.2) | 12 (23.5) | — |

| Heterosexual | 35 (64.8) | 39 (76.5) | .21b |

| CDC classification, n (%) | |||

| A: 1–3 (asymptomatic) | 22 (40.7) | 24 (47.1) | — |

| B: 1–3 (symptomatic) | 17 (31.5) | 13 (25.5) | .75b |

| C: 1–3 (AIDS) | 15 (27.8) | 14 (27.5) | — |

| Viral suppression (<400 copies per mL on most recent viral load test), n (%) | 28 (57.1) | 30 (66.7) | .34b |

| Dialysis since last medical visit | 1 (2.0) | 0 (0) | .99b |

| Adolescent education, n (%) | |||

| No high school diploma or in high school | 29 (53.7) | 27 (52.9) | |

| HS or GED equivalent | 15 (27.8) | 19 (37.3) | |

| Some college or no bachelor’s | 9 (16.7) | 5 (9.8) | .46b |

| Surrogate education, n (%) | |||

| No high school diploma or in high school | 13 (24.1) | 10 (19.6) | — |

| HS or GED equivalent | (37.0) | 22 (43.1) | — |

| Some college or higher education | 21 (38.9) | 19 (37.3) | .77b |

| Family income, n (%)c | |||

| Equal of below federal poverty line | 28 (51.9) | 24 (47.1) | — |

| 101%–200% of federal poverty line | 4 (7.4) | 11 (21.6) | — |

| 201%–300% of federal poverty line | 3 (5.6) | 5 (9.8) | — |

| >300% of federal poverty line | 13 (24.1) | (9.8) | — |

| Unknown | 6 (11.1) | (11.8) | 11b |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 54 (100.0) | 50 (98.0) | — |

| Married or living together | 0 (0) | 1 (2.0) | .49b |

| Housing status, n (%)c | |||

| Living in own house or apartment | 48 (88.9) | 45 (88.2) | — |

| Living in someone else’s house or apartment | 5 (9.3) | 5 (9.8) | — |

| A shelter or someone else’s house or apartment | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | — |

| Other | 0 (0) | 1 (2.0) | .93b |

CDC, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; GED, general equivalency diploma; HS, high school; —, not applicable.

t test.

Fisher’s exact test. No statistically significant difference indicating success of randomization.

Family income data are from families because adolescents did not always know their family income.

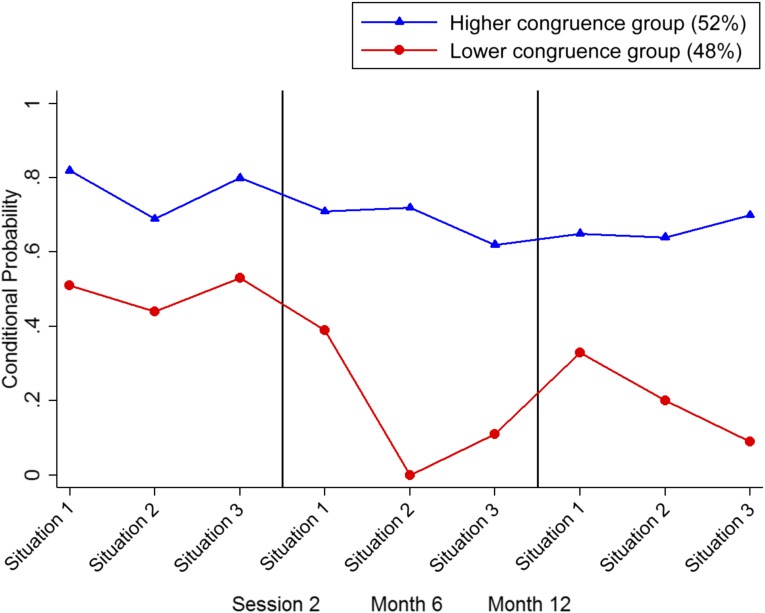

Model Results: Congruence

The LLCA of dyads revealed 2 latent classes: class 1 (N = 50 [52%]) and class 2 (N = 46 [48%]; Fig 2, Supplemental Table 4). Congruence probabilities were high in class 1 in all 3 situations (.82, .69, and .80, respectively) immediately postintervention (session 2) and remained moderately high at 6-month (.71, .72, and .62, respectively) and 12-month (.65, .64, and .70, respectively) follow-ups. Situation-specific congruence probabilities in class 2 were low (.51, .44, and .53, respectively) immediately postintervention (session 2) and declined longitudinally. FACE pACP dyads were more likely to be in the high congruence class compared with control dyads (odds ratio: 3.11 [95% confidence interval (CI): 1.14 to 8.46]; P = .03), controlling for age, sex, race, parental education, family income, and transmission mode. A post hoc analysis revealed treatment congruence had no effect on HIV-medication adherence or viral suppression.

FIGURE 2.

Results of the LLCA on treatment congruence over time. Situation 1 indicates a long hospital stay with many treatments and a low chance of survival. Situation 2 indicates a physical disability with 24-hour nursing care. Situation 3 indicates mental disability with 24-hour nursing care. Congruence means that the family understood and accurately reported what that adolescent would want for end-of-life treatment preferences.

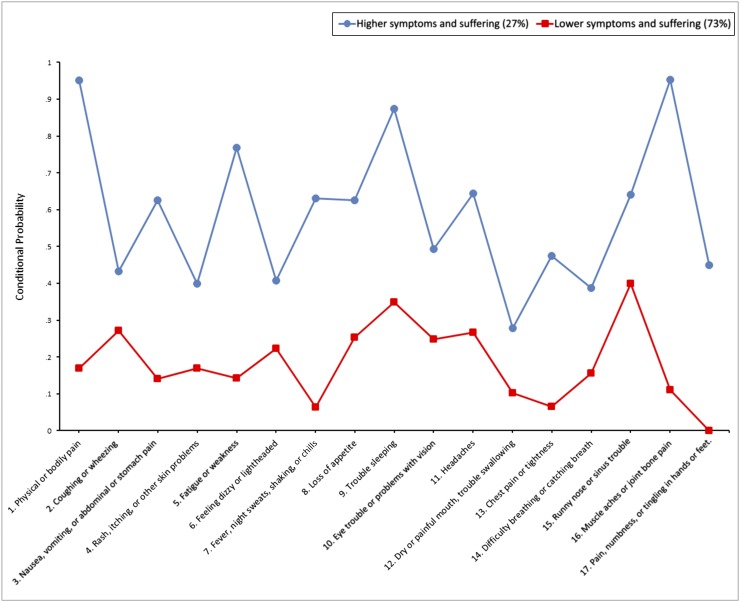

Model Results: Symptoms

The LCA identified 2 latent classes or groups on the basis of the 17 dichotomous measures of HIV-specific symptoms (Fig 3, Supplemental Table 3). Of adolescents, 27% were classified into class 1 (the higher symptoms and suffering group), and 73% were classified into class 2 (the lower symptoms and suffering group). The probabilities of symptoms and suffering were much higher in class 1 compared with class 2.

FIGURE 3.

Results of the LCA on HIV-specific symptoms at 12 months postintervention.

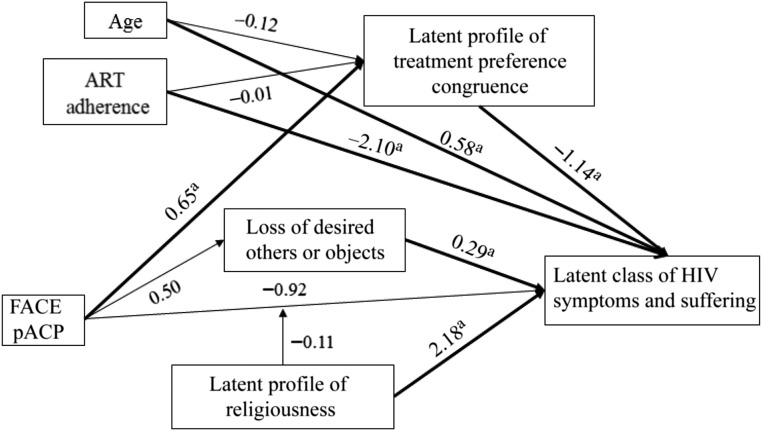

Model Results: Path Analysis

A Bayesian estimation of the model reached convergence. The 95% CI for the difference between the observed and the model estimated χ2 statistics (−24.920 to 20.643) centered around 0, and posterior predictive P value (P = .567) indicated an almost perfect fit. The path analysis model results are shown in Fig 4. FACE pACP did not directly affect HIV symptom patterns (β = −.92; 95% CI: −3.86 to 1.66). FACE pACP increased the likelihood of higher dyadic treatment congruence (β = .65; 95% CI: 0.04 to 1.28). Higher treatment congruence decreased the likelihood of being classified in the higher symptoms and suffering class (β = −1.14; 95% CI: −2.55 to −0.24). As such, FACE pACP indirectly negatively affected symptom classification through treatment congruence (β = −.686; 95% CI: −2.14 to −0.006); that is, patients in the intervention group were less likely to be classified into the higher symptoms and suffering class. The variable loss of desired others and objects directly predicted the effect of the intervention on symptom classification (β = .29; 95% CI: 0.06 to 0.60); however, it did not mediate the FACE pACP intervention effect on symptoms because FACE pACP did not significantly affect loss of desired others or objects (β = .50; 95% CI: −0.85 to 1.86). Religiousness and/or spirituality had a significant positive effect on symptom classification (β = 2.18; 95% CI: 0.22 to 4.70); that is, patients in the high religiousness and/or spirituality class were more likely to have a higher probability of being in the higher symptoms class. However, religiousness and/or spirituality did not significantly moderate the FACE pACP intervention effect because its interaction with the intervention was not statistically significant (β = −.11; 95% CI: −2.82 to 2.86). Adolescents who reported taking their antiretroviral medication (≥90% of the time) had a lower probability of being in the higher symptoms class (β = −2.10; 95% CI: −3.93 to −0.82). Older adolescents were more likely to be in the higher symptoms class (β = .58; 95% CI: 0.14 to 1.10). Additionally, sex, ethnicity, and perinatal HIV infection did not significantly affect classification of HIV symptoms.

FIGURE 4.

Results of the path analysis model. Covariates that do not have a significant slope coefficient are not included in the diagram. a Significant at the P < .05 level. ART, antiretroviral therapy.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study in which a full theoretical model of pACP is tested and is the first longitudinal randomized clinical trial of pACP, the gold standard of research.55 The hypotheses that there would be a direct intervention effect between FACE pACP and HIV-latent symptom class was not supported. However, the a priori hypothesis that there would be an indirect intervention effect through dyadic treatment congruence on classification of HIV symptoms and suffering was supported. FACE pACP families were significantly more likely to understand adolescents’ treatment preferences. In turn, if families accurately reported their understanding of their adolescents’ end-of-life treatment preferences, their adolescents were more likely to be in the lower symptoms and suffering class at 12 months postintervention. In contrast, families in the lower congruence class had adolescents more likely to be in the higher symptoms and suffering class. Higher congruence suggests good communication and social support, which are demonstrated to decrease HIV-specific symptoms in adults.19

Consistent with theories of coping through problem solving12–18 and the representational approach to patient illness interventions,28–31,56 pACP gave adolescents control associated with lower symptoms, particularly with pain. The impact of higher dyadic congruence worked through 2 mechanisms to decrease symptoms and suffering: (1) social support (experienced through respectful and authentic conversations about adolescents’ understanding of their illness) and (2) control (through being asked to make choices about treatments in poor-outcome situations with their family’s support in a safe environment).54 Future research could be used to explore whether higher congruence decreases disease-specific symptoms through enhanced immune function57 by decreasing stress (weekly supportive facilitation) and providing problem solving support19,58 (“breaking the ice” so that families understand their adolescents’ treatment preferences), through patient representation of illness28–31 (changing adolescents’ representations of illness and acting on new information), and/or through control17,18 (giving adolescents a voice so that preferences are honored by family, shared with their physician, and documented in the medical record).

Consistent with adult studies,59,60 facilitated conversations improve families’ understanding of their adolescents’ end-of-life treatment preferences. Although results in adult studies have been inconsistent, some adult studies have revealed an ACP effect on disease-specific symptoms. These inconsistencies may reflect lack of scientific rigor (as described in systematic reviews61,62) and/or failure to examine treatment congruence as a mediator of symptom outcomes.

One dimension of threat appraisal (loss of desired others or objects) directly increased the likelihood of being in the higher symptoms class regardless of study arm. Consistent with our pilot study25 and previous research with children,26,27 loss of others and objects is a significant pathway to psychological symptoms over and above the effects of stressful events per se.

Religiousness directly increased the likelihood of adolescents being in the high symptoms latent class, with pain dominating symptoms. Future research may reveal the underlying mechanism, such as a belief that physical pain is a test of faith to be endured and not masked by medication63 or a belief that redemption is achieved through suffering.64,65 Clinicians might refer interested adolescents for consultation with a hospital-based chaplain to conduct a spiritual assessment to understand how beliefs affect youths’ health experiences.66,67

Strengths

This culturally sensitive model with a traditionally understudied and underserved population had high participation rates and a significant benefit (reducing HIV-specific symptoms and suffering). FACE pACP may contribute to health equity.63,68,69 FACE pACP has features to foster replication and ease of implementation, including a structured conversation guide, family engagement, certified nonphysician facilitators, face-to-face sessions, physician communication, and formalized documentation.

Limitations

Only adolescents who had an identified surrogate decision-maker were eligible, which limited generalizability70 and was a challenge for all dyadic research.71 Findings may not generalize beyond African American and Hispanic adolescents living with HIV or AIDS (an understudied cohort). Although viral load provided an indicator of disease progression, CD4+ and comorbidity data were not collected. pACP conversations did not increase HIV-medication adherence in this sample, so this is an unlikely explanation for the symptom benefit.72

Whether early pACP will result in goal-concordant care73 is unknown, although FACE pACP did maintain congruence over the course of 1 year, even as adolescents changed their mind. Importantly, the ideal of patient-centered care supports early pACP for adolescents living with HIV37–39 because less than one-fourth of adolescents wanted to wait until hospitalization or they were dying to talk about pACP. Although prognostication may have a role in ACP,73,74 prognostication is complicated with HIV and AIDS comorbidities, medication adherence, and treatment side effects.75 As noted earlier, most adolescent patients have indicated a strong preference for beginning these conversations while healthy, at time of diagnosis, or when first experiencing disease-specific symptoms.37–39,76,77

Conclusions

FACE pACP successfully decreased symptom burden, a goal of patient-centered care.63,78 This model is responsive to calls for culturally sensitive interventions,63,79–82 a beneficial approach that effectively provided access to and provision of pACP to underserved racial and ethnic groups. Study results provide an evidence base for effective pACP in pediatric, hospital-based HIV clinics to achieve quality improvement and to support policy recommendations to implement pACP as an individualized and structured part of care for interested families.83–87 Trial findings may inform care and future interventions for young people with other serious illnesses.

Acknowledgments

The following institutions and individuals in addition to the coauthors participated in the FACE pACP 4972 Adolescent Palliative Care Consortium: Coinvestigators Ms Linda Briggs (Respecting Choices); Natella Rakhmanina, Pamela Hinds, Tomas Silber, and Kathleen Ennis-Durstein (Children’s National Health System); Megan Wilkins, Thomas Wride, and Ryan Heine (St Jude Children’s Research Hospital); Lawrence Friedman and Dr Ana Garcia (University of Miami Miller School of Medicine); Rana Sohail and Patricia Houston (Howard University Hospital); and Ana Puga, Sandra Navarro, and Jamie Blood (Children’s Diagnostic and Treatment Center).

We thank our many clinical coordinators and RAs; we remember with deep gratitude the data manager and consultants who died during the course of the study, Saied Goudarzi, John R. Anderson, and Robert M. Malow; and we thank the members of our Safety Monitoring Committee, Beatrice Kraus, Connie Trexler, and Bruce Rapkin, who guided us safely through this protocol and our adolescent and family participants without whom this research could not have been completed.

Glossary

- ACP

advance care planning

- CI

confidence interval

- FACE pACP

family-centered pediatric advance care planning

- LCA

latent class analysis

- LLCA

longitudinal latent class analysis

- pACP

pediatric advance care planning

- RA

research assistant

- SoTP

statement of treatment preferences

Footnotes

Dr Lyon conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Wang designed the longitudinal model for the study from its inception, conducted the analysis, tested the statistical models, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and supervised Ms Cheng; Dr Garvie coordinated data collection, collected data, contributed to the interpretation of the data, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; Drs Dallas and Garcia coordinated data collection, collected data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Ms. Cheng assisted in the data verification, data analysis, and creation of tables and figures and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Ms Briggs codesigned one of the data collection instruments, supervised the fidelity of the intervention implementation, and critically reviewed the manuscript; Drs D’Angelo and Flynn coordinated data collection, contributed to the interpretation of the data, and critically reviewed and revised the manuscript; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This trial has been registered at www.clinicaltrials.gov (identifier NCT01289444).

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Funded by US National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), National Institutes of Health (NIH) award R01NR012711-05, the NIH National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR000075), and the Clinical and Translational Science Institute at Children's National (CTSI-CN). These institutions were not involved in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; or preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript. This content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NINR, NIH, or CTSI-CN. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: Dr Lyon developed and adapted the Lyon Advance Care Planning Survey adolescent and surrogate versions used in session 1 of the 3-session intervention. Ms Briggs developed and adapted the statement of treatment preferences used to obtain study results on treatment agreement between the adolescent and family; the other authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.Neilan AM, Karalius B, Patel K, et al. ; Pediatric HIV/AIDS Cohort Study; International Maternal Adolescent and Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Network . Association of risk of viremia, immunosuppression, serious clinical events, and mortality with increasing age in perinatally human immunodeficiency virus-infected youth. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(5):450–460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention HIV among youth. 2018. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/age/youth/. Accessed June 5, 2018

- 3.Reif S, Pence BW, Hall I, Hu X, Whetten K, Wilson E. HIV diagnoses, prevalence and outcomes in nine southern states. J Community Health. 2015;40(4):642–651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNAIDS All in to #EndAdolescentAIDS. 2015. Available at: www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/20150217_ALL_IN_brochure.pdf. Accessed June 5, 2018

- 5.Rietjens JAC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, et al. ; European Association for Palliative Care . Definition and recommendations for advance care planning: an international consensus supported by the European Association for Palliative Care. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18(9):e543–e551 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. . Defining advance care planning for adults: a consensus definition from a multidisciplinary Delphi panel. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;53(5):821–832.e1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lyon ME, Garvie PA, Briggs L, He J, McCarter R, D’Angelo LJ. Development, feasibility, and acceptability of the family/adolescent-centered (FACE) advance care planning intervention for adolescents with HIV. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(4):363–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lyon ME, Garvie PA, McCarter R, Briggs L, He J, D’Angelo LJ. Who will speak for me? Improving end-of-life decision-making for adolescents with HIV and their families. Pediatrics. 2009;123(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/123/2/e199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lyon ME, Garvie PA, Briggs L, et al. . Is it safe? Talking to teens with HIV/AIDS about death and dying: a 3-month evaluation of family centered advance care (FACE) planning - anxiety, depression, quality of life. HIV AIDS (Auckl). 2010;2:27–37 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.National Cancer Institute; National Institutes of Health Research-tested intervention programs (RTIPs). Available at: https://rtips.cancer.gov/rtips/programDetails.do?programId=17054015. Accessed June 5, 2018

- 11.Hammes BJ, Briggs L. Respecting Choices: Advance Care Planning Facilitator Manual-Revised. La Crosse, WI: Gundersen Lutheran Medical Foundation; 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Folkman S, Greer S. Promoting psychological well-being in the face of serious illness: when theory, research and practice inform each other. Psychooncology. 2000;9(1):11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company; 1984 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fawzy FI, Fawzy NW. Psychoeducational interventions and health outcomes In: Glaser R, Kiecolt-Glaser JK, eds. Handbook of Human Stress and Immunity. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1994:365–402 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fawzy FI, Fawzy NW, Hyun CS, et al. . Malignant melanoma. Effects of an early structured psychiatric intervention, coping, and affective state on recurrence and survival 6 years later. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50(9):681–689 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fawzy FI, Cousins N, Fawzy NW, Kemeny ME, Elashoff R, Morton D. A structured psychiatric intervention for cancer patients. I. Changes over time in methods of coping and affective disturbance. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47(8):720–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geers AL, Rose JP, Fowler SL, Rasinski HM, Brown JA, Helfer SG. Why does choice enhance treatment effectiveness? Using placebo treatments to demonstrate the role of personal control. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2013;105(4):549–566 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elliot AJ, Turiano NA, Infurna FJ, Lachman ME, Chapman BP. Lifetime trauma, perceived control, and all-cause mortality: results from the Midlife in the United States study. Health Psychol. 2018;37(3):262–270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ashton E, Vosvick M, Chesney M, et al. . Social support and maladaptive coping as predictors of the change in physical health symptoms among persons living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2005;19(9):587–598 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS Med. 2010;7(7):e1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Tarakeshwar N, Hahn J. Religious coping methods as predictors of psychological, physical and spiritual outcomes among medically ill elderly patients: a two-year longitudinal study. J Health Psychol. 2004;9(6):713–730 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pargament KI, Koenig HG, Tarakeshwar N, Hahn J. Religious struggle as a predictor of mortality among medically ill elderly patients: a 2-year longitudinal study. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161(15):1881–1885 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ironson G, Stuetzle R, Ironson D, et al. . View of God as benevolent and forgiving or punishing and judgmental predicts HIV disease progression. J Behav Med. 2011;34(6):414–425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trevino KM, Pargament KI, Cotton S, et al. . Religious coping and physiological, psychological, social, and spiritual outcomes in patients with HIV/AIDS: cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(2):379–389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schembari B, Wang J, Cheng YI, Lyon ME. Does religious coping moderate the relationship between threat appraisal and decisional conflict among HIV infected youth participants in and end-of-life decision-making intervention? In: 36th Annual Conference of the Association of Death Education and Counseling; April 23–26, 2014; Baltimore, MD Abstract 299973 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sandler IN, Ayers TS, Wolchik SA, et al. . The family bereavement program: efficacy evaluation of a theory-based prevention program for parentally bereaved children and adolescents. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(3):587–600 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sandler IN, Kim-Bae LS, MacKinnon D. Coping and negative appraisal as mediators between control beliefs and psychological symptoms in children of divorce. J Clin Child Psychol. 2000;29(3):336–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Donovan HS, Ward S. A representational approach to patient education. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2001;33(3):211–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Donovan HS, Ward SE, Song MK, Heidrich SM, Gunnarsdottir S, Phillips CM. An update on the representational approach to patient education. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2007;39(3):259–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ward S, Donovan H, Gunnarsdottir S, Serlin RC, Shapiro GR, Hughes S. A randomized trial of a representational intervention to decrease cancer pain (RIDcancerPain). Health Psychol. 2008;27(1):59–67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Donovan HS, Ward SE, Sereika SM, et al. . Web-based symptom management for women with recurrent ovarian cancer: a pilot randomized controlled trial of the WRITE Symptoms intervention. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(2):218–230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beck AT, Steer RA, Brown GK. Beck Depression Inventory Manual. 2nd ed. San Antonio, TX: The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace and Co; 1996 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shaffer D, Schwab-Stone M, Fisher P, et al. . The Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children-Revised Version (DISC-R): I. Preparation, field testing, interrater reliability, and acceptability. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32(3):643–650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Power C, Selnes OA, Grim JA, McArthur JC. HIV Dementia Scale: a rapid screening test. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr Hum Retrovirol. 1995;8(3):273–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dallas RH, Wilkins ML, Wang J, Garcia A, Lyon ME. Longitudinal pediatric palliative care: quality of life & spiritual struggle (FACE): design and methods. Contemp Clin Trials. 2012;33(5):1033–1043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lyon ME, D’Angelo LJ, Dallas RH, et al. . A randomized clinical trial of adolescents with HIV/AIDS: pediatric advance care planning. AIDS Care. 2017;29(10):1287–1296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lyon ME, McCabe MA, Patel KM, D’Angelo LJ. What do adolescents want? An exploratory study regarding end-of-life decision-making. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(6):529.e1–529.e6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lyon M, Garvie P, Briggs L, He J, McCarter R, D’Angelo L. Do families know what adolescents want? An end-of-life (EOL) survey of adolescents with HIV/AIDS and their families. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(2, suppl 1):S4–S5 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lyon ME, Dallas RH, Garvie PA, et al. ; Adolescent Palliative Care Consortium . Paediatric advance care planning survey: a cross-sectional examination of congruence and discordance between adolescents with HIV/AIDS and their families [published online ahead of print September 21, 2017]. BMJ Support Palliat Care. doi: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2016-001224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Towey J; Aging with Dignity Five wishes. Available at: https://fivewishes.org/. Accessed September 17, 2018

- 41.Barkley RA. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder: A Clinical Workbook. 1st ed. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 42.Patrick K, Spear B, Holt K, Sofka D. Bright Futures in Practice: Physical Activity. Arlington, VA: National Center for Education in Maternal and Child Health; 2001:1–222 [Google Scholar]

- 43.Gortmaker SL, Lenderking WR, Clark C, Lee S, Glenn Fowler M, Oleske JM; ACTG 219 Team . Development and use of a pediatric quality of life questionnaire in AIDS clinical trials: reliability and validity of the General Health Assessment for Children In: Drotar D, ed. Measuring Health-Related Quality of Life in Children and Adolescents: Implications for Research, Practice. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, Associates, Inc; 1998:219–235 [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lyon ME, Williams PL, Woods ER, et al. . Do-not-resuscitate orders and/or hospice care, psychological health, and quality of life among children/adolescents with acquired immune deficiency syndrome. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(3):459–469 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harris SK, Sherritt LR, Holder DW, Kulig J, Shrier LA, Knight JR. Reliability and validity of the brief multidimensional measure of religiousness/spirituality among adolescents. J Relig Health. 2008;47(4):438–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cotton S, McGrady ME, Rosenthal SL. Measurement of religiosity/spirituality in adolescent health outcomes research: trends and recommendations. J Relig Health. 2010;49(4):414–444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Masters KS, Carey KB, Maisto SA, et al. . Psychometric examination of the brief multidimensional measure of religiousness/spirituality among college students. Int J Psychol Relig. 2009;19(2):106–120 [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lyon ME, Kimmel AL, Cheng YI, Wang J. The role of religiousness/spirituality in health-related quality of life among adolescents with HIV: a latent profile analysis. J Relig Health. 2016;55(5):1688–1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Walsh JC, Mandalia S, Gazzard BG. Responses to a 1 month self-report on adherence to antiretroviral therapy are consistent with electronic data and virological treatment outcome. AIDS. 2002;16(2):269–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bentler PM, Chou CP. Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociol Methods Res. 1987;16(1):78–117 [Google Scholar]

- 51.Muthén B, Asparouhov T. Bayesian structural equation modeling: a more flexible representation of substantive theory. Psychol Methods. 2012;17(3):313–335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Muthén BO. Beyond SEM: general latent variable modeling. Behaviormetrika. 2002;29(1):81–117 [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus User’s Guide. 7th ed.Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 1998–2012. Available at: https://www.statmodel.com/download/usersguide/Mplus%20user%20guide%20Ver_7_r3_web.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dallas RH, Kimmel A, Wilkins ML, et al. ; Adolescent Palliative Care Consortium . Acceptability of family-centered advanced care planning for adolescents with HIV. Pediatrics. 2016;138(6):e20161854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lotz JD, Jox RJ, Borasio GD, Führer M. Pediatric advance care planning: a systematic review. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/131/3/e873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Leventhal H, Nerenz DR, Steele DJ. Illness representations and coping with health threats In: Baum A, Taylor SE, Singer JE, eds. Social Psychological Aspects of Health. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; 1984:219–252. Handbook of Psychology and Health Vol 4 [Google Scholar]

- 57.Morey JN, Boggero IA, Scott AB, Segerstrom SC. Current directions in stress and human immune function. Curr Opin Psychol. 2015;5:13–17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnson MO, Elliott TR, Neilands TB, Morin SF, Chesney MA. A social problem-solving model of adherence to HIV medications. Health Psychol. 2006;25(3):355–363 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Song MK, Ward SE, Happ MB, et al. . Randomized controlled trial of SPIRIT: an effective approach to preparing African-American dialysis patients and families for end of life. Res Nurs Health. 2009;32(3):260–273 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Detering KM, Hancock AD, Reade MC, Silvester W. The impact of advance care planning on end of life care in elderly patients: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;340:c1345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Houben CHM, Spruit MA, Groenen MTJ, Wouters EFM, Janssen DJA. Efficacy of advance care planning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2014;15(7):477–489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chan RJ, Webster J, Bowers A. End-of-life care pathways for improving outcomes in caring for the dying. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(2):CD008006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cain CL, Surbone A, Elk R, Kagawa-Singer M. Culture and palliative care: preferences, communication, meaning, and mutual decision making. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55(5):1408–1419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Paisius E. Elder Paisius: I wish you many years. 2013. Available at: www.orthodoxchurchquotes.com/2013/07/10/elder-paisus-i-wish-you-many-years-but-not/. Accessed June 6, 2018

- 65.VanderWeele TJ, Balboni TA, Koh HK. Health and spirituality. JAMA. 2017;318(6):519–520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. . Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the consensus conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(10):885–904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Balboni TA, Balboni M, Enzinger AC, et al. . Provision of spiritual support to patients with advanced cancer by religious communities and associations with medical care at the end of life. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(12):1109–1117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bona K, Wolfe J. Disparities in pediatric palliative care: an opportunity to strive for equity. Pediatrics. 2017;140(4):e20171662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hansen ED, Mitchell MM, Smith T, Hutton N, Keruly J, Knowlton AR. Chronic pain, patient-physician engagement, and family communication associated with drug-using HIV patients’ discussing advanced care planning with their physicians. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2017;54(4):508–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lee BC, Houston PE, Rana SR, Kimmel AL, D’Angelo LJ, Lyon ME; Adolescent Palliative Care Consortium . Who will speak for me? Disparities in palliative care research with “unbefriended” adolescents living with HIV/AIDS. J Palliat Med. 2017;20(10):1135–1138 [Google Scholar]

- 71.Quinn C, Dunbar SB, Clark PC, Strickland OL. Challenges and strategies of dyad research: cardiovascular examples. Appl Nurs Res. 2010;23(2):e15–e20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Lyon ME, Dallas R, Wilkins M, Cheng YI, Wang J. Does advance care planning increase medication adherence in HIV+ teens? (ind143432). In: 122nd Annual Convention of the American Psychological Association; August 7–10, 2014; Washington, DC [Google Scholar]

- 73.Billings JA, Bernacki R. Strategic targeting of advance care planning interventions: the Goldilocks phenomenon. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(4):620–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Jacobs S, Perez J, Cheng YI, Sill A, Wang J, Lyon ME. Adolescent end of life preferences and congruence with their parents’ preferences: results of a survey of adolescents with cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(4):710–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Merlin J, Pahuja M, Selwyn P Palliative care: issues in HIV/AIDS in adults. 2017. Available at: https://www.uptodate.com/contents/palliative-care-issues-in-hiv-aids-in-adults. Accessed June 6, 2018

- 76.Wiener L, Ballard E, Brennan T, Battles H, Martinez P, Pao M. How I wish to be remembered: the use of an advance care planning document in adolescent and young adult populations. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(10):1309–1313 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wiener L, Zadeh S, Battles H, et al. . Allowing adolescents and young adults to plan their end-of-life care. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):897–905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Wolfe J, Hammel JF, Edwards KE, et al. . Easing of suffering in children with cancer at the end of life: is care changing? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1717–1723 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Johnston EE, Alvarez E, Saynina O, Sanders L, Bhatia S, Chamberlain LJ. Disparities in the intensity of end-of-life care for children with cancer. Pediatrics. 2017;140(4):e20170671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Loggers ET, Maciejewski PK, Paulk E, et al. . Racial differences in predictors of intensive end-of-life care in patients with advanced cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(33):5559–5564 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Linton JM, Feudtner C. What accounts for differences or disparities in pediatric palliative and end-of-life care? A systematic review focusing on possible multilevel mechanisms. Pediatrics. 2008;122(3):574–582 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Flores G; Committee on Pediatric Research . Technical report–racial and ethnic disparities in the health and health care of children. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/125/4/e979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Institute of Medicine Committee on Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families In: Field MJ, Behrman RE, eds. When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Section on Hospice and Palliative Medicine; Committee on Hospital Care . Pediatric palliative care and hospice care commitments, guidelines, and recommendations. Pediatrics. 2013;132(5):966–972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Committee on Approaching Death: Addressing Key End of Life Issues; Institute of Medicine . Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Feudtner C, Zhong W, Faerber J, Dai D, Feinstein J. Appendix F: pediatric end-of-life and palliative care: epidemiology and health service use In: Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015:533–572 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Friebert S, Williams C NHPCO’s facts and figures: pediatric palliative & hospice care in America. 2015. Available at: https://www.nhpco.org/sites/default/files/public/quality/Pediatric_Facts-Figures.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2018