Insurance mandates for children’s autism increase service use, but do they also increase out-of-pocket spending?

Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The health care costs associated with treating autism spectrum disorder (ASD) in children can be substantial. State-level mandates that require insurers to cover ASD-specific services may lessen the financial burden families face by shifting health care spending to insurers.

METHODS:

We estimated the effects of ASD mandates on out-of-pocket spending, insurer spending, and the share of total spending paid out of pocket for ASD-specific services. We used administrative claims data from 2008 to 2012 from 3 commercial insurers, and took a difference-in-differences approach in which children who were subject to mandates were compared with children who were not. Because mandates have heterogeneous effects based on the extent of children’s service use, we performed subsample analyses by calculating quintiles based on average monthly total spending on ASD-specific services. The sample included 106 977 children with ASD across 50 states.

RESULTS:

Mandates increased out-of-pocket spending but decreased the share of spending paid out of pocket for ASD-specific services on average. The effects were driven largely by children in the highest-spending quintile, who experienced an average increase of $35 per month in out-of-pocket spending (P < .001) and a 4 percentage point decline in the share of spending paid out of pocket (P < .001).

CONCLUSIONS:

ASD mandates shifted health care spending for ASD-specific services from families to insurers. However, families in the highest-spending quintile still spent an average of >$200 per month out of pocket on these services. To help ease their financial burden, policies in which children with higher service use are targeted may be warranted.

What’s Known on This Subject:

State-level mandates that require insurers to cover services for autism increase service use, especially among high spenders. It is unknown whether mandates also increase out-of-pocket spending, which may exacerbate the financial burden already faced by families.

What This Study Adds:

We find that insurance mandates increased out-of-pocket spending but reduced the share of spending paid out of pocket. The effects were driven largely by high spenders, which suggests that mandates have heterogeneous effects based on a child’s service use.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is characterized by abnormal social and communicative development, narrow interests, and repetitive activity.1 Recommended treatments for ASD vary in type and intensity given its clinical heterogeneity and may include behavioral, speech, occupational, and physical therapy and other educational interventions.2 The financial burden accompanying ASD can be heavy3,4; the authors of 1 study report that an ASD diagnosis is associated with an additional $3400 in annual health care costs and nearly $16 000 in annual non–health care costs, such as special education services,5 whereas another study finds that the cost of caring for an individual with ASD ranges from 1.5 to 2.6 million dollars over the course of a lifetime.6 Even as they experience an increased need for additional income to pay for treatments, parents of children with ASD work less to provide or coordinate care.7

Until recently, commercial insurers often excluded or minimally covered many ASD-related services, citing high costs and the lack of strong evidentiary support for available treatments.8,9 To overcome these barriers, 46 states and the District of Columbia have enacted laws mandating that commercial insurers cover some treatments for ASD since 2001. Details of the mandates differ across states, but they typically target specific age groups and include expenditure caps on total spending per person-year that range from $12 000 to $50 000.8

The overarching aim of mandates is to increase access to home- and community-based care for children with ASD who are commercially insured. However, mandates do not affect all children with ASD who are commercially insured; they apply only to children with fully insured plans because the Employee Retirement Income Security Act exempts self-insured plans (in which the employer assumes the financial risk of providing health care benefits to their employees) from state-level insurance regulations.

Mandates are effective at improving access to care for children with ASD who are eligible. The authors of 2 recent studies found that mandates led to an increase in both the number of children in treatment with a diagnosis of ASD and the use of and spending on ASD-related services; they also found that the magnitude of these effects grew over time.8,10 These results are promising, but increases in service use due to the passage of mandates may inadvertently result in higher out-of-pocket spending among families of children with ASD, especially if the child's ASD is severe or the family has a health plan with high cost-sharing requirements. Although insurance coverage has generally been shown to reduce financial burdens faced by patients,11,12 the change in out-of-pocket spending after an expansion of coverage ultimately depends on the extent to which patients respond to increased coverage with increased service use.13,14

In this study, we estimate the effects of state-level ASD insurance mandates on out-of-pocket spending (which includes copays, coinsurance, and deductibles), insurer spending, and the share of total spending paid out of pocket for ASD-specific services. The clinical heterogeneity of ASD results in vastly different treatment needs, and differences in benefit designs mean some insurance plans are more generous than others, so it is important to understand how mandates affect children differently. Therefore, we examine whether mandates have heterogeneous effects on the basis of the total amount of a child’s ASD-related health care spending.

Methods

Our data consisted of outpatient and inpatient claims from the Health Care Cost Institute15 for the years 2008–2012, which included children insured through Aetna, Humana, and UnitedHealthcare. The study sample comprised 106 977 children <21 years old who had at least 2 claims associated with the International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification ASD diagnosis code 299.xx during the study period. Roughly 30% of these children had fully insured plans subject to mandates. We did not include enrollees who had a behavioral service carve-out because we were unable to observe their claims in our data (∼11% of our sample). We also excluded children with individually insured plans (∼0.2% of our sample) as well as children in the top 0.1% of total spending to account for a small number of outliers with extreme levels of spending. Spending measures were adjusted to 2012 dollars by using the Personal Health Care Index from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Office of the Actuary. This study was exempted from review by the University of Pennsylvania Institutional Review Board.

During the study period, mandates were implemented by Illinois, South Carolina, and Texas in 2008, by Arizona, Florida, Louisiana, New Mexico, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin in 2009, by Colorado, Connecticut, Montana, and New Jersey in 2010, by Arkansas, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, Missouri, New Hampshire, Nevada, and Vermont in 2011, and by California, Delaware, Michigan, New York, Rhode Island, Virginia, and West Virginia in 2012.16,17 The unit of analysis was the child-month, so we created a binary variable to indicate the month a state’s mandate was implemented.

Our dependent variables of interest were average monthly out-of-pocket spending on covered ASD-specific services, average monthly spending on covered ASD-specific services made by the insurer, and the share of total spending on covered ASD-specific services paid out of pocket. We defined ASD-specific services as claims with an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification code of 299.xx. Out-of-pocket spending included deductibles, copays, and coinsurance. Insurer spending was calculated as the difference between total spending and any spending paid out of pocket.

To see if mandates had heterogeneous effects, we divided our sample into quintiles, which were determined by average total (ie, insurer plus out-of-pocket) spending on all ASD-specific services for any month that the child appeared in our data. By creating quintiles, we can compare how mandates affected children with ASD who had higher levels of service use with how they affected children with ASD who had lower levels of service use.

To identify the effect of mandates, we used a difference-in-differences framework to exploit the staggered implementation of mandates across states and the exemptions for self-insured plans that were based on the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, which means that a large share of children with ASD living in states with mandates were not covered by them. The model compared changes in spending before and after mandates were introduced for those who were subject to mandates (ie, children who met the age criteria and had fully insured plans) with the changes in spending before and after mandates were introduced for those children not subject to mandates. Thus, the comparison group included children who lived in states with mandates but were not subject to the mandates because they were enrolled in self-insured plans, children who lived in states with mandates but did not meet the age criteria, and children who lived in states without mandates.

We estimated adjusted linear regressions at the child-month level; covariates included sex, age (estimated on the basis of July 1 in their birth year given data limitations), plan type (health maintenance organization, point of service, preferred provider organization, and other), an indicator of whether the plan was a high deductible health plan, and month and year fixed effects. We also included state fixed effects to account for time-invariant characteristics. SEs were clustered at the child level.

Results

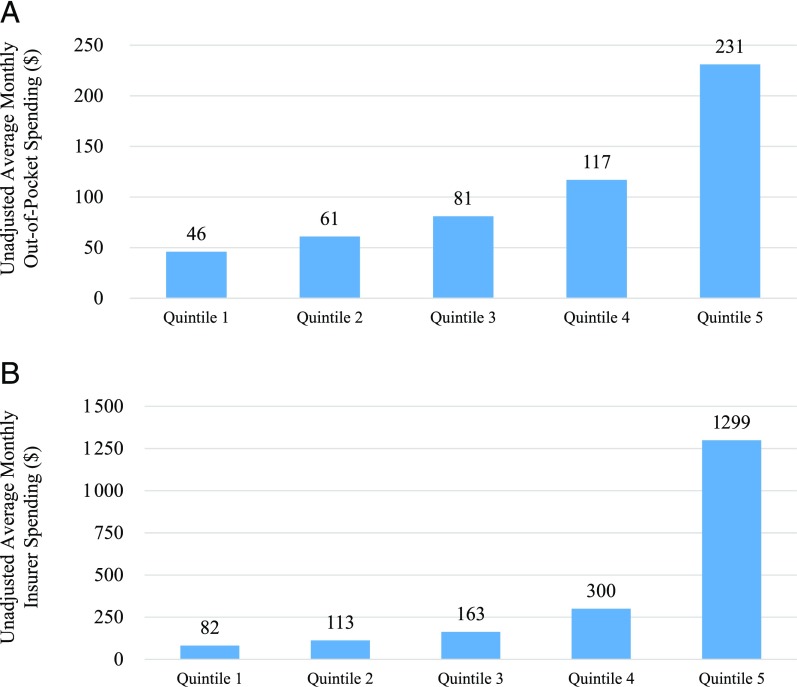

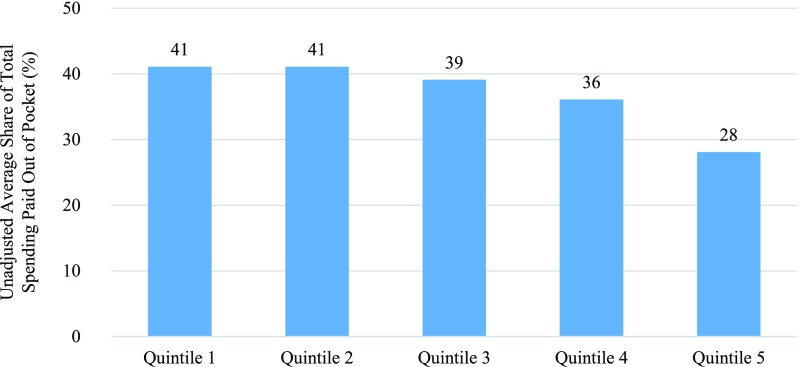

From 2008 to 2012, unadjusted average out-of-pocket spending on ASD-specific services was $107 per child-month, whereas an average of $391 was spent by the insurer per child-month. Spending differed substantially at the high and low ends of the distribution. In the highest-spending quintile, average out-of-pocket spending was $231 per child-month, and the average insurer spending was $1299 per child-month; in the lowest-spending quintile, out-of-pocket spending was $46 per child-month on average, and spending by the insurer was $82 per child-month on average (Fig 1). Over this same time period, the share of spending paid out of pocket was smallest for families with higher spending (Fig 2). On average, families in the highest-spending quintile paid 28% of total spending on ASD-specific services out of pocket; families in the lowest-spending quintile paid 41%.

FIGURE 1.

A, Unadjusted average monthly out-of-pocket spending for ASD-specific services by spending quintile, 2008–2012. B, Unadjusted average monthly insurer spending for ASD-specific services by spending quintile, 2008–2012. The final sample included 106 977 children. Quintiles were determined by average monthly spending on ASD-specific services in any month between 2008 and 2012; quintile 1 refers to the lowest spenders.

FIGURE 2.

Unadjusted average monthly share of total spending paid out of pocket on ASD-specific services by spending quintile, 2008–2012. The final sample included 106 977 children. Quintiles were determined by average monthly spending on ASD-specific services in any month between 2008 and 2012; quintile 1 refers to the lowest spenders.

After mandates were implemented, changes in out-of-pocket spending on ASD-specific services were concentrated among families in the highest quintile of spending whose monthly out-of-pocket spending increased by $35 (P < .001) on average. However, insurer spending in this quintile increased by nearly $270 (P < .001) per child-month (Table 1). By comparison, there was a significant decrease of $10 in out-of-pocket spending per child-month for families in the fourth quintile (P < .01).

TABLE 1.

Adjusted Average Monthly Out-of-Pocket Spending, Insurer Spending, and Share of Spending Paid Out of Pocket for ASD-Specific Services by Spending Quintile, 2008–2012

| Mandate Eligible | Mandate Ineligible | Change Attributable to Mandates | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mandate in Place | No Mandate in Place | Mandate in Place | No Mandate in Place | ||

| Quintile 1 (lowest spenders) | |||||

| Out-of-pocket spending, $ | 51 | 49 | 46 | 44 | 0 |

| Insurer spending, $ | 75 | 70 | 84 | 83 | 4 |

| Share of out-of-pocket spending, % | 46 | 46 | 39 | 40 | 1 |

| Quintile 2 | |||||

| Out-of-pocket spending, $ | 67 | 65 | 60 | 60 | 1 |

| Insurer spending, $ | 108 | 94 | 119 | 115 | 10** |

| Share of out-of-pocket spending, % | 45 | 47 | 39 | 40 | −1 |

| Quintile 3 | |||||

| Out-of-pocket spending, $ | 90 | 89 | 79 | 78 | 0 |

| Insurer spending, $ | 148 | 132 | 173 | 166 | 9* |

| Share of out-of-pocket spending, % | 44 | 46 | 37 | 38 | −1 |

| Quintile 4 | |||||

| Out-of-pocket spending, $ | 130 | 134 | 117 | 111 | −10** |

| Insurer spending, $ | 263 | 265 | 311 | 307 | −5 |

| Share of out-of-pocket spending, % | 41 | 42 | 35 | 35 | −1 |

| Quintile 5 (highest spenders) | |||||

| Out-of-pocket spending, $ | 307 | 262 | 219 | 209 | 35*** |

| Insurer spending, $ | 1657 | 1415 | 1211 | 1239 | 270*** |

| Share of out-of-pocket spending, % | 28 | 32 | 27 | 27 | −4*** |

The final sample included 106 977 children. Quintiles were determined by average monthly spending on ASD-specific services between 2008 and 2012. Spending measures were adjusted for sex, age, insurance plan type, and state, month, and year fixed effects. SEs were clustered at the child level. Mandate eligible refers to whether the child had a fully insured plan and met the age criteria for the state’s mandate in a given month. Mandate in place refers to whether the child’s state had a mandate in place in a given month. Children may contribute months to multiple columns.

P < .001

P < .01

P < .05.

Mandates resulted in a modest decline in the share of spending paid out of pocket for ASD-specific services; the effect was again concentrated among high spenders. In the highest-spending quintile, families of children with ASD who were subject to the mandate experienced a 3.7 percentage point decline (P < .001) in the share of spending paid out of pocket on average. Families in the bottom 4 quintiles did not experience statistically significant changes in the share of spending paid out of pocket as a result of mandates.

Discussion

State-level insurance mandates that require insurers to cover certain treatments for children’s ASD increase the use of and spending on ASD-specific services,13 but this may result in a larger financial burden for families. In the current study, we found that out-of-pocket spending increased for some families of children with ASD who were subject to a mandate, but because insurer spending increased relatively more than out-of-pocket spending, the share of spending paid out of pocket declined for the families of these children. Notably, the largest effects occurred in the highest-spending quintile, in which average out-of-pocket spending increased by $35 each month, and the average share of spending paid out of pocket decreased by 3.7 percentage points among families of children who were eligible for mandates. Out-of-pocket spending did not change for families of children with ASD in the bottom 3 quintiles who were subject to mandates, and the share of total spending paid out of pocket did not change in the bottom 4 quintiles as a result of mandates.

Our findings contrast with those of 1 study that reports a reduction in out-of-pocket spending after the passage of ASD mandates, although their measures of out-of-pocket spending were survey-based binary indicators that denoted any out-of-pocket spending and out-of-pocket spending >$750.18 Our findings also differ from those of other studies that found modest reductions in out-of-pocket spending on behavioral health and/or substance use disorder treatment as a result of mental health parity legislation.19,20 One reason for the opposite findings may be that mandates that target children with ASD resulted in a much larger change in service use than mental health parity legislation.10,19 Thus, even if the insurer shoulders the majority of the newfound costs, families can end up spending more out of pocket when increases in service use are substantial.

These results suggest that mandates confer some financial protections to families with higher levels of spending on ASD-specific services. If health care spending approximates the service needs of a child, these results also suggest that mandates have larger effects for children with higher service needs and, potentially, more severe ASD. However, these results might stem from inequalities in access to treatments for ASD.21 For example, children with higher levels of spending may have families with additional disposable income to pay for services, or children with lower levels of spending may reside in areas with limited provider supply22 or have families that are less capable of advocating for their needs or are uncertain about which services are covered.23 Such disparities could be exacerbated when ASD mandates are enacted.

Families in the highest-spending quintile paid >$200 out of pocket per month on average. This financial burden may be worthy of further efforts to ameliorate its effects, especially for low-income families.24 High spending could be driven by failures of care delivery and the use of ineffective and expensive services.25 Indeed, services that do not alleviate symptoms can even paradoxically lead to increased use of those services if clinicians and families do not fully consider the effectiveness of ongoing treatments.26 To address these concerns, payers should more carefully assess service quality and appropriateness and encourage ASD treatments with strong evidentiary support.

The financial burden also could be alleviated by services from other systems because children with ASD typically receive care from multiple systems concurrently (eg, education).27 The coordination of school-based services and health care is limited; barriers to coordination include administrative hurdles, the lack of funding for better case management, privacy laws, and even differences in culture and language in education and health care.28 Developing creative mechanisms to bridge the gap between different service silos could improve the efficiency of care delivery to children with ASD and potentially negate the need for some treatments altogether.

A number of limitations should be mentioned. First, ASD diagnoses could not be verified by clinical review, although previous research has found that this identification strategy has high positive predictive value.29 Second, some families of children with ASD report service use that is paid for completely out of pocket, but our measure of out-of-pocket spending only captures the portion of family spending paid for via insurance and likely underestimates the true cost of care. In addition, the measure of financial burden was limited to information available in insurance claims, and we did not have information on the family’s household income or other sociodemographic characteristics that would allow for a more precise measure of financial strain. Third, we cannot be sure that self-insured plans did not opt to adhere to mandates; if they chose to cover ASD-specific services, our findings would be attenuated. Finally, we did not directly control for some aspects of the mandates, such as expenditure caps (although we did include state fixed effects), nor were we able to measure the concentration of care providers, who play a critical role in translating insurance coverage into increased service use and improved outcomes.

Conclusions

Spending on ASD-specific services increased for both families and insurers after state-level insurance mandates for children with ASD were implemented, but these effects were driven by children with higher levels of spending on ASD-specific services. Because the relative increase was larger for insurers than for families, the share of spending paid out of pocket declined. Although it is unsurprising that mandates had a larger impact on families with higher levels of spending, our study serves as a reminder that policies are not one-size-fits-all. Researchers must examine whether policies like mandates have heterogeneous effects on subsamples of children with ASD because their service needs and financial burdens vary extensively.

Glossary

- ASD

autism spectrum disorder

Footnotes

Dr Candon conceptualized and designed the study, performed statistical analyses, drafted the initial manuscript, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content; Drs Barry, Marcus, Epstein, Xie, and Mandell conceptualized and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, designed the data collection instruments, collected data, and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content; Dr Kennedy-Hendricks conceptualized and designed the study and critically reviewed the manuscript for important intellectual content; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Funded by grant R01MH096848 (principal investigators: Drs Barry and Mandell). Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Myers SM, Johnson CP; American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children With Disabilities . Management of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):1162–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leslie DL, Martin A. Health care expenditures associated with autism spectrum disorders. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(4):350–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Croen LA, Najjar DV, Ray GT, Lotspeich L, Bernal P. A comparison of health care utilization and costs of children with and without autism spectrum disorders in a large group-model health plan. Pediatrics. 2006;118(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/118/4/e1203 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lavelle TA, Weinstein MC, Newhouse JP, Munir K, Kuhlthau KA, Prosser LA. Economic burden of childhood autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/133/3/e520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Buescher AV, Cidav Z, Knapp M, Mandell DS. Costs of autism spectrum disorders in the United Kingdom and the United States. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(8):721–728 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kogan MD, Strickland BB, Blumberg SJ, Singh GK, Perrin JM, van Dyck PC. A national profile of the health care experiences and family impact of autism spectrum disorder among children in the United States, 2005-2006. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/122/6/e1149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mandell DS, Barry CL, Marcus SC, et al. . Effects of autism spectrum disorder insurance mandates on the treated prevalence of autism spectrum disorder. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(9):887–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouder JN, Spielman S, Mandell DS. Brief report: quantifying the impact of autism coverage on private insurance premiums. J Autism Dev Disord. 2009;39(6):953–957 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barry CL, Epstein AJ, Marcus SC, et al. . Effects of state insurance mandates on health care use and spending for autism spectrum disorder. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(10):1754–1761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hwang W, Weller W, Ireys H, Anderson G. Out-of-pocket medical spending for care of chronic conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2001;20(6):267–278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Finkelstein A, McKnight R. What did Medicare do? The initial impact of Medicare on mortality and out of pocket medical spending. J Public Econ. 2008;92(7):1644–1668 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pauly MV. The economics of moral hazard: comment. Am Econ Rev. 1968;58(3 part 1):531–537 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wagstaff A, Lindelow M. Can insurance increase financial risk? The curious case of health insurance in China. J Health Econ. 2008;27(4):990–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaynor M. Introducing the health care cost institute. Health Management, Policy and Innovation. 2012;1(1):35–36 [Google Scholar]

- 16.Autism Speaks State initiatives. 2015. Available at: https://www.autismspeaks.org/state-initiatives. Accessed August 11, 2016

- 17.National Conference of State Legislatures Autism and insurance coverage. Available at: www.ncsl.org/research/health/autism-and-insurance-coverage-state-laws.aspx. Accessed August 11, 2016

- 18.Chatterji P, Decker SL, Markowitz S. The effects of mandated health insurance benefits for autism on out-of-pocket costs and access to treatment. J Policy Anal Manage. 2015;34(2):328–353 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Azrin ST, Huskamp HA, Azzone V, et al. . Impact of full mental health and substance abuse parity for children in the Federal Employees Health Benefits Program. Pediatrics. 2007;119(2). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/119/2/e452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barry CL, Chien AT, Normand SL, et al. . Parity and out-of-pocket spending for children with high mental health or substance abuse expenditures. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/131/3/e903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Benevides TW, Carretta HJ, Lane SJ. Unmet need for therapy among children with autism spectrum disorder: results from the 2005-2006 and 2009-2010 National Survey of Children with Special Health Care Needs. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(4):878–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Murphy MA, Ruble LA. A comparative study of rurality and urbanicity on access to and satisfaction with services for children with autism spectrum disorders. Rural Special Education Quarterly. 2012;31(3):3–11 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baller JB, Barry CL, Shea K, Walker MM, Ouellette R, Mandell DS. Assessing early implementation of state autism insurance mandates. Autism. 2016;20(7):796–807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newacheck PW, Inkelas M, Kim SE. Health services use and health care expenditures for children with disabilities. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):79–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berwick DM, Hackbarth AD. Eliminating waste in US health care. JAMA. 2012;307(14):1513–1516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Green G. Evaluating claims about treatments for autism In: Maurice C, Green G, Luce SC, eds. Behavioral Intervention for Young Children With Autism: A Manual for Parents and Professionals. Austin, TX: PRO-ED; 1996:15–28 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cidav Z, Marcus SC, Mandell DS. Home- and community-based waivers for children with autism: effects on service use and costs. Intellect Dev Disabil. 2014;52(4):239–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Power TJ, Blum NJ, Guevara JP, Jones HA, Leslie LK. Coordinating mental health care across primary care and schools: ADHD as a case example. Adv Sch Ment Health Promot. 2013;6(1):68–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Burke JP, Jain A, Yang W, et al. . Does a claims diagnosis of autism mean a true case? Autism. 2014;18(3):321–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]