From the 2016 NSCH, an estimated 1.5 million US children aged 3 to 17 years (2.50%) had ever received an ASD diagnosis and currently had the condition.

Abstract

Video Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To estimate the national prevalence of parent-reported autism spectrum disorder (ASD) diagnosis among US children aged 3 to 17 years as well as their treatment and health care experiences using the 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH).

METHODS:

The 2016 NSCH is a nationally representative survey of 50 212 children focused on the health and well-being of children aged 0 to 17 years. The NSCH collected parent-reported information on whether children ever received an ASD diagnosis by a care provider, current ASD status, health care use, access and challenges, and methods of treatment. We calculated weighted prevalence estimates of ASD, compared health care experiences of children with ASD to other children, and examined factors associated with increased likelihood of medication and behavioral treatment.

RESULTS:

Parents of an estimated 1.5 million US children aged 3 to 17 years (2.50%) reported that their child had ever received an ASD diagnosis and currently had the condition. Children with parent-reported ASD diagnosis were more likely to have greater health care needs and difficulties accessing health care than children with other emotional or behavioral disorders (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anxiety, behavioral or conduct problems, depression, developmental delay, Down syndrome, intellectual disability, learning disability, Tourette syndrome) and children without these conditions. Of children with current ASD, 27% were taking medication for ASD-related symptoms, whereas 64% received behavioral treatments in the last 12 months, with variations by sociodemographic characteristics and co-occurring conditions.

CONCLUSIONS:

The estimated prevalence of US children with a parent-reported ASD diagnosis is now 1 in 40, with rates of ASD-specific treatment usage varying by children’s sociodemographic and co-occurring conditions.

What’s Known on This Subject:

Previous studies over the last 20 years have shown an increasing prevalence of autism spectrum disorder (ASD) among US children. Moreover, families of children with ASD have reported greater health care needs and challenges compared with children with other emotional or behavioral conditions.

What This Study Adds:

In this study, we present new nationally representative data on the prevalence of ASD, reported health care challenges, and estimates on ASD-specific behavioral and medication treatments. The estimated prevalence of US children with parent-reported diagnosis of ASD is now 1 in 40.

Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a complex neurodevelopmental disorder characterized by persistent deficits in social communication and interactions and restricted, repetitive patterns of behaviors or interests.1 The prevalence of diagnosed ASD has increased in the United States and globally within the last 30 to 40 years.2–17 Although not fully understood, this increase likely results from multiple factors including broadening diagnostic criteria, increased provider ascertainment at earlier ages, increased parent awareness, and an increase in some risk factors such as births to older parents.18–20

The challenges of ASD are many and varied. Compared with the general population, children with ASD experience an increased prevalence of co-occurring conditions, such as asthma, eczema, gastrointestinal disturbances, and seizures.21 In addition, 83% of children with ASD have a co-occurrence of ≥1 non-ASD developmental diagnosis.22 Children with ASD have greater health services needs, including therapy,23 emergency department care,24 physician visits, and hospitalizations.25 Increased and unpredictable needs for health care visits can also affect parents’ employment,26 increase financial and time burdens,27 and disrupt family routines.28 Few national studies have compared the disparities in health services and challenges for families having a child with ASD.27 Although ASD currently has no known cure, the most common treatments to ameliorate the symptoms include behavioral, language, speech, physical, and occupational therapies.29 Pharmacological agents have been Food and Drug Administration–approved to treat irritability associated with ASD symptoms.30 The costs of caring for a child with ASD in the United States, including health care and non–health care services, was estimated at $17 081 per year beyond the costs of caring for a child without ASD, with total societal costs of caring for children with ASD estimated at $11.5 billion in 2011.31

The 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health (NSCH), a nationally and state-representative survey of 50 212 children, ages 0 to 17 years, offers the opportunity to address certain gaps in our knowledge. This study provides the most recent nationally representative estimate on children with ASD. Although the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) can provide ASD prevalence estimates,9 the NSCH has a larger sample, and can explore other aspects of the child’s condition, including ASD-specific treatments, plus an in-depth examination of their health care needs and experiences. The 2016 NSCH also offers the first opportunity to provide national estimates on ASD-specific drug and behavioral treatments.

Methods

The 2016 NSCH was designed, directed, and funded by the Health Resources and Services Administration’s Maternal and Child Health Bureau. The survey was conducted by the US Census Bureau, which used a national address-based sample for data collection by either Web or mail. The NSCH provides information on the health and well-being of children on the basis of information from their parents or other caregivers (hereafter referred to as “parents”). Questionnaires were available in English or Spanish. The 2016 NSCH used a 2-phased data collection approach: (1) an initial household screener assessed the presence of children, their basic demographic characteristics, and special health care need status and (2) a substantive, age-specific topical questionnaire completed by parents of one randomly selected child per household. Children with special health care needs had a higher probability of selection compared with other children to increase the sample size among this population.

From June 2016 to February 2017, topical questionnaires were completed. The proportion of households known to include children that completed the topical questionnaire was 69.7%. The overall weighted response rate, which includes nonresponse to the screener to identify whether households include children, was 40.7%. Additional details about the survey methodology are available elsewhere.32 This study was a secondary analysis of publicly available data. The data were collected under Title 13, US Code, Section 8(b). All data products are reviewed for adherence to privacy protection and disclosure avoidance guidelines by the Census Bureau’s Disclosure Review Board.

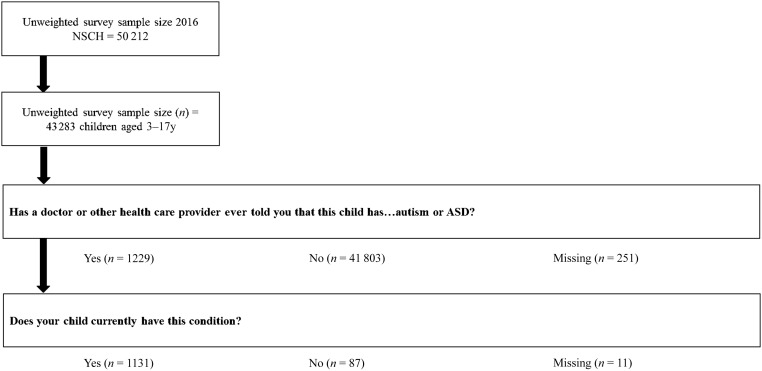

Analyses for this study were limited to 43 283 children aged 3 to 17 years and excluded children ≤2 years (n = 6929). Parents were asked if a doctor or other health care provider had ever told them that their child had “Autism or Autism Spectrum Disorder, including diagnoses of Asperger’s Disorder or Pervasive Developmental Disorder.” Parents who responded “Yes” were subsequently asked if their child currently has the condition (see Fig 1). For this analysis, children identified as having ASD were those with a parent report of (1) ever told by a doctor and/or other health care provider that their child had ASD and (2) child currently has ASD. In 87 cases, the parent reported that the child was ever diagnosed with ASD but did not currently have the condition (7.1%). These cases were not considered as having ASD for this analysis. Children whose parents did not know or refused to answer either of the ASD questions were excluded from analyses (n = 262; 0.6%)

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of survey-participant progress through the autism and ASD questions, NSCH, 2016.

The prevalence of ASD was estimated overall and by selected demographic, socioeconomic, and childbirth characteristics in Table 1. We also provided unadjusted and adjusted prevalence rate ratios (PRRs). In Table 2 we examined (1) health care service use including medical and behavioral treatments for ASD symptoms and receipt of specialist care other than mental health treatment and/or counseling; and (2) parental frustration, access to treatment, and quality of care received including receipt of care in a medical home. We defined medical home using the American Academy of Pediatrics framework, specifically whether33 (1) the child had a personal physician or nurse; (2) the child had a usual place for sick care; (3) the family reported no problems obtaining needed referrals; (4) the family reported receipt of family centered care; and (5) the family reported receipt of effective care coordination, if needed. All 5 criteria needed to be met for a child to have a medical home.

TABLE 1.

Point Prevalence of Parent-Reported Current ASD Among Children Aged 3–17 Years According to Selected Demographic, Socioeconomic, and Birth Characteristics, United States, 2016

| Characteristics | No. in Sample (Unweighted) | No. With ASD (Unweighted) | No. With ASD (Weighted) in Thousands | Weighted Prevalence of ASD, % | 95% CI | Unadjusted PRR (95% CI) | Adjusted PRRa (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All children aged 3–17 y | 43 021 | 1131 | 1529 | 2.5 | 2.23–2.81 | — | — |

| Age, y | |||||||

| 3–5 | 7530 | 123 | 235 | 1.97 | 1.41–2.74 | 0.74 (0.51–1.07) | 0.81 (0.56–1.18) |

| 6–11 | 14 925 | 422 | 641 | 2.61 | 2.15–3.15 | 0.98 (0.77–1.26) | 1.02 (0.79–1.30) |

| 12–17 | 20 566 | 586 | 653 | 2.65 | 2.27–3.10 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Sex | |||||||

| Boys | 22 064 | 917 | 1208 | 3.88 | 3.41–4.41 | 3.63 (2.71–4.85)b | 3.46 (2.55–4.69)b |

| Girls | 20 957 | 214 | 321 | 1.07 | 0.82–1.39 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Race and/or ethnicity | |||||||

| Hispanic | 4734 | 125 | 368 | 2.43 | 1.76–3.35 | 0.94 (0.67–1.34) | 0.93 (0.64–1.36) |

| Non-Hispanic white | 30 215 | 790 | 815 | 2.57 | 2.26–2.93 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 2542 | 80 | 220 | 2.79 | 2.03–3.81 | 1.08 (0.77–1.52) | 0.81 (0.54–1.21) |

| Non-Hispanic other and/or multiracial | 5530 | 136 | 126 | 1.96 | 1.52–2.51 | 0.76 (0.57–1.01) | 0.75 (0.55–1.03) |

| Highest level of education by parent in household | |||||||

| Less than high school | 973 | 27 | 146 | 2.56 | 1.56–4.16 | 0.94 (0.64–1.80) | 0.73 (0.38–1.40) |

| High school, GED, vocational | 5377 | 160 | 350 | 2.98 | 2.19–4.06 | 1.26 (0.89–1.77) | 0.88 (0.58–1.31) |

| Some college and/or technical school | 9630 | 289 | 323 | 2.42 | 1.96–2.98 | 1.02 (0.79–1.31) | 0.80 (0.59–1.09) |

| College degree or higher | 26 012 | 632 | 672 | 2.37 | 2.05–2.74 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Family structurec | |||||||

| 2 parents, married | 31 108 | 752 | 832 | 2.12 | 1.85–2.43 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| 2 parents, unmarried | 2649 | 86 | 167 | 3.36 | 2.08–5.37 | 1.58 (0.97–2.59) | 1.49 (0.91–2.45) |

| Single mother | 5446 | 196 | 378 | 3.86 | 3.02–4.93 | 1.82 (1.37–2.41)b | 1.47 (1.05–2.05)b |

| Other | 3092 | 84 | 128 | 2.29 | 1.46–3.58 | 1.08 (0.68–1.72) | 1.02 (0.58–1.80) |

| Household poverty | |||||||

| <100% FPL | 4230 | 165 | 455 | 3.51 | 2.64–4.66 | 1.79 (1.29–2.47)b | 2.06 (1.31–3.22)b |

| 100%–199% FPL | 6910 | 219 | 338 | 2.48 | 1.84–3.34 | 1.27 (0.85–1.88) | 1.38 (0.91–2.07) |

| 200%–399% FPL | 13 172 | 333 | 378 | 2.3 | 1.87–2.84 | 1.17 (0.87–1.59) | 1.27 (0.94–1.70) |

| ≥400% FPL | 18 709 | 415 | 357 | 1.97 | 1.62–2.39 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Region | |||||||

| Northeast | 8148 | 246 | 267 | 2.74 | 2.19–3.42 | 1.23 (0.83–1.82) | 1.20 (0.80–1.80) |

| Midwest | 11 266 | 283 | 353 | 2.71 | 2.22–3.31 | 1.22 (0.83–1.78) | 1.14 (0.79–1.64) |

| South | 12 640 | 343 | 577 | 2.46 | 2.04–2.95 | 1.10 (0.76–1.60) | 0.99 (0.68–1.43) |

| West | 10 967 | 259 | 332 | 2.23 | 1.61–3.07 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Nativity | |||||||

| US born | 41 230 | 1101 | 1495 | 2.58 | 2.30–2.91 | 2.08 (1.25–3.47)b | 2.34 (1.30–4.21)b |

| Foreign born | 1530 | 30 | 34 | 1.24 | 0.75–2.03 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Child born preterm | |||||||

| Yes | 4633 | 187 | 279 | 4.03 | 3.10–5.23 | 1.78 (1.33–2.39)b | 1.71 (1.26–2.31)b |

| No | 37 757 | 923 | 1206 | 2.26 | 1.99–2.58 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| Age of mother at child’s birth, y | |||||||

| 18–24 | 7394 | 228 | 383 | 2.8 | 2.24–3.50 | 1.00 (referent) | 1.00 (referent) |

| 25–29 | 10 340 | 287 | 353 | 2.35 | 1.87–2.95 | 0.84 (0.61–1.16) | 0.96 (0.68–1.36) |

| 30–34 | 12 726 | 298 | 358 | 2.21 | 1.72–2.84 | 0.79 (0.61–1.16) | 0.95 (0.64–1.39) |

| 35–39 | 7923 | 185 | 269 | 2.84 | 2.11–3.82 | 1.01 (0.70–1.47) | 1.20 (0.81–1.79) |

| ≥40 | 2178 | 64 | 61 | 2.4 | 1.52–3.75 | 0.85 (0.52–1.41) | 1.03 (0.61–1.75) |

Note: n = 262 are missing ASD status. Data source: 2016 NSCH. GED, General Educational Development; —, not applicable.

Adjusted for all other demographic, sociodemographic, and birth characteristics shown.

Significant value.

Categories are mutually exclusive.

TABLE 2.

PRRs of Having Selected Health Care Characteristics According to Parent-Reported ASD Status and Other EBDs, United States, 2016

| Children With ASD (n = 1131), Weighted % | Children With Other EBDsa (n = 7795), Weighted % | All Other Children (n = 33 014), Weighted % | Children With ASD Versus Children With Other EBDs,a Adjusted PRR (95% CI)b | Children With ASD Versus All Other Children, Adjusted PRR (95% CI)b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Insurance statusc | |||||

| Public only | 46.9 | 40.2 | 28.4 | 1.12 (0.98–1.28) | 1.68 (1.47–1.91)d |

| Private only | 39.9 | 46.6 | 59.8 | 0.88 (0.77–1.02) | 0.66 (0.57–0.75)d |

| Other | 11.0 | 9.1 | 5.4 | 1.22 (0.88–1.70) | 2.10 (1.53–2.87)d |

| Uninsured | 2.1 | 4.1 | 6.4 | 0.53 (0.30–0.93)d | 0.35 (0.20–0.60)d |

| Visited health care provider in past 12 mo | 93.9 | 89.6 | 83.6 | 1.05 (1.01–1.08)d | 1.12 (1.09–1.15)d |

| Had a usual place for preventive care | 94.8 | 94.7 | 91.3 | 1.00 (0.95–1.05) | 1.04 (0.99–1.09) |

| Any dental visit in past 12 mo | 84.3 | 88.8 | 87.1 | 0.96 (0.91–1.02) | 0.96 (0.90–1.01) |

| Received treatment or counseling from mental health provider | 45.9 | 39.6 | 3.0 | 1.28 (1.13–1.45)d | 15.18 (12.76–18.05)d |

| Big problem to get mental health treatment or counseling (among those who needed to see a mental health professional) | 22.9 | 15.9 | 8.5 | 1.44 (1.04–1.98)d | 2.71 (1.46–5.05)d |

| Used medication because of emotions or behavior | 42.1 | 37.2 | 0.4 | 1.18 (1.02–1.36)d | 84.56 (59.19–120.81)d |

| Saw specialist other than mental health professional | 35.0 | 27.2 | 11.7 | 1.32 (1.11–1.57)d | 2.97 (2.52–3.50)d |

| Big problem to get the specialist care needed (among those who needed to see a specialist other than mental health professional) | 18.4 | 12.0 | 4.3 | 1.40 (0.86–2.29) | 3.61 (2.03–6.45)d |

| Used alternative health care or treatment | 15.5 | 11.4 | 5.4 | 1.43 (1.07–1.92)d | 2.83 (2.15–3.71)d |

| Did not get needed health care | 10.8 | 8.3 | 2.1 | 1.37 (0.93–2.02) | 5.63 (3.86–8.21)d |

| Type of care not received (among those who did not get needed care) | |||||

| Medical and/or dental | 32.1 | 63.2 | 86.0 | 0.56 (0.36–0.88)d | 0.41 (0.26–0.64)d |

| Hearing and/or vision | 24.5e | 27.7 | 31.7 | 0.83 (0.39–1.77) | 0.69 (0.32–1.52) |

| Mental health | 63.1 | 42.4 | 9.5e | 1.46 (1.07–1.98)d | 6.82 (3.45–13.51)d |

| Other | 27.6 | 20.4 | 5.8e | 1.27 (0.64–2.53) | 4.02 (1.74–9.28)d |

| Usually or always parents frustrated in efforts to get services | 14.9 | 7.4 | 1.5 | 2.02 (1.45–2.82)d | 10.53 (7.51–14.77)d |

| Child had a special education or early intervention plan | 87.5 | 41.3 | 6.1 | 2.15 (1.99–2.32)d | 13.83 (12.37–15.45)d |

| Age at time of first plan, y (among those with a special education or early intervention plan) | |||||

| 0–2 | 20.2 | 15.7 | 24.2 | 1.12 (0.84–1.49) | 0.83 (0.62–1.11) |

| 3–5 | 57.7 | 31.3 | 39.8 | 1.77 (1.53–2.05)d | 1.46 (1.23–1.73)d |

| 6–8 | 14.1 | 33.5 | 22.5 | 0.45 (0.34–0.60)d | 0.61 (0.44–0.85)d |

| ≥9 | 8.0 | 19.6 | 13.5 | 0.50 (0.34–0.72)d | 0.65 (0.42–1.01) |

| Currently receiving services under plan (among those with a special education or early intervention plan) | 84.3 | 78.0 | 37.3 | 1.07 (1.01–1.14)d | 2.27 (1.97–2.61)d |

| Ever received special services to meet developmental needs | 89.0 | 40.0 | 9.3 | 2.22 (2.05–2.41)d | 9.32 (8.52–10.18)d |

| Age when began receiving these services, y (among those who received special services) | |||||

| 0–2 | 27.8 | 22.7 | 25.8 | 1.14 (0.92–1.42) | 1.15 (0.93–1.42) |

| 3–5 | 52.0 | 35.8 | 48.9 | 1.42 (1.22–1.66)d | 1.06 (0.91–1.22) |

| 6–8 | 12.7 | 29.1 | 19.6 | 0.46 (0.35–0.62)d | 0.62 (0.45–0.85)d |

| ≥9 | 7.6 | 12.4 | 5.7 | 0.66 (0.41–1.06) | 1.25 (0.72–2.17) |

| Currently receiving special services for developmental needs (among those who received special services) | 76.2 | 59.2 | 23.7 | 1.27 (1.17–1.37)d | 3.30 (2.82–3.87)d |

| Had a medical home | 31.6 | 41.5 | 50.0 | 0.77 (0.65–0.91)d | 0.63 (0.54–0.73)d |

| Had at least 1 personal doctor or nurse | 78.4 | 76.7 | 71.4 | 1.03 (0.95–1.11) | 1.10 (1.02–1.18)d |

| Had usual sources for sick care | 87.6 | 80.7 | 78.7 | 1.09 (1.03–1.15)d | 1.11 (1.05–1.17)d |

| Received family-centered care (among those with a health care visit in the past 12 mo) | 72.6 | 82.7 | 87.2 | 0.89 (0.82–0.96)d | 0.84 (0.77–0.91)d |

| Had no problems getting referrals when needed (among those who needed a referral) | 66.5 | 71.5 | 81.2 | 0.93 (0.80–1.08) | 0.81 (0.71–0.93)d |

| Received all needed components of care coordination (among those who needed care coordination) | 46.0 | 60.2 | 76.3 | 0.76 (0.65–0.88)d | 0.59 (0.51–0.68)d |

Note: n = 1343 are missing data on EBD status (n = 262 are missing data on autism, and the rest are missing data on at least 1 of the other EBDs we assessed). Data source: 2016 NSCH.

EBDs include ADHD, anxiety, behavioral or conduct problems, depression, developmental delay, Down syndrome, intellectual disability, learning disability, and Tourette syndrome. In addition, 92.3% of children with ASD were reported to have other EBDs.

Adjusted for age, sex, and race and/or ethnicity.

Other insurance includes private, public, and unspecified.

Significant value.

Estimates are considered unreliable and should be used with caution. Data have a relative SE >30%.

We additionally explored how the health care experiences of children with ASD and their families differed from children with other diagnosed emotional, behavioral, and developmental conditions (EBDs) (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder [ADHD], anxiety, behavioral and/or conduct problems, depression, developmental delay, Down syndrome, intellectual disability, learning disability, Tourette syndrome), and those without ASD or other EBDs. EBDs were identified analogously to ASD: affirmative responses to both questions of whether the parent was “ever told child had condition” and whether “child currently has the condition.” Health care experiences included services used, difficulties accessing needed care, and current receipt of services under a special education or early intervention plan. We estimated weighted percentages, PRRs, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) comparing children with ASD to children with other EBDs but not ASD, and all other children without EBDs or ASD. The PRRs were adjusted for child age, sex, and race and/or ethnicity.

Finally, we examined factors associated with the likelihood of receiving medication and/or behavioral treatment of ASD-related symptoms among children with ASD and health insurance using multivariable logistic regression. Covariates included sociodemographic characteristics, years since diagnosis (calculated by subtracting age at diagnosis from child’s current age), provider type for ASD diagnosis, and presence of co-occurring conditions. (Supplemental Table 4 provides prevalence estimates of co-occurring conditions.) Additionally, the medication model included behavioral treatment, whereas the behavioral treatment model included medication. Adjusted PRRs and 95% CIs are reported.

Missing data for child sex, race, and ethnicity were imputed by using hot deck methods during the weighting process, whereas the household income-to-poverty ratio was imputed by using regression methods. All estimates were weighted by using survey sampling weights available from the Census Bureau to produce estimates that are representative of the US noninstitutionalized child population aged 3 to 17 years. These weights reflect the inverse of the probability that the address was selected for the survey and were adjusted to account for the higher likelihood that children with special health care needs would be selected for the topical interview, as well as nonresponse. Weighted analyses were conducted by using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) and SAS-callable SUDAAN 11.0 (RTI International, Research Triangle Park, NC).

Results

From these nationally representative data, we estimated the point-prevalence of parent-reported ASD diagnosis in 2016 to be 2.50 per 100 children. This represents an estimated 1.5 million children aged 3 to 17 years (Table 1). After adjustment for selected demographic, socioeconomic, and birth characteristics, ASD prevalence in boys was 3.46 times higher than in girls. Additionally, ASD prevalence was 47% higher for children with single mothers than children in 2-parent, married households, 2.06 times as high for children from households <100% of the federal poverty level (FPL) compared with children from households ≥400% of the FPL and 71% higher in children born preterm than term. Prevalence was 2.34 times as high for US-born than foreign-born children. The same variables were also significant when unadjusted.

Children with a parent-reported ASD diagnosis (including those who had other EBDs) had more needs and difficulties regarding health care access and use compared with children without an ASD diagnosis but who had other EBDs, and children with parent-reported ASD also had more needs and difficulties compared with other children without ASD or EBDs (Table 2). Compared with children with other EBDs, children with ASD were more likely in the past 12 months to have received mental health counseling, seen a specialist besides a mental health professional, used alternative health care or treatments, ever have a special education or early intervention plan, and currently receive special services for developmental needs. However, children with ASD were also more likely to have parents who reported difficulties with health care. They were 44% more likely to report problems getting mental health treatment, 46% more likely to report not receiving needed mental health care, 2.02 times more likely to report being usually or always frustrated in getting services, 23% less likely to have a medical home, and 24% less likely to receive needed care coordination. Children with ASD also had greater needs and difficulties compared with all other children (without other EBDs).

Of children with a parent-reported ASD diagnosis, ∼27% were taking medication for ASD-related symptoms. Children with ASD from households where the highest level of education was less than high school were 74% more likely to be currently taking medication for ASD symptoms compared with children from households with at least a college degree (Table 3). In addition, current medication use varied regionally and was higher among children who were diagnosed >7 years ago, who had attention-deficit disorder (ADD) and/or ADHD or behavioral and/or conduct problems, and who received behavioral treatment of their ASD symptoms in the past 12 months. Children in 2-parent, unmarried households were less likely than children in 2-parent, married households to be taking medication for ASD.

TABLE 3.

Percentage of Children Aged 3–17 Years Who Took Medication for ASD or Received Behavioral Treatment of ASD, Among Children Aged 3–17 Years Who Currently Have ASD and are Insured, United States, 2016

| Medication for ASD (n = 323) | Behavioral Treatment of ASD (n = 686) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted % | Adjusted PRRa | 95% CI | Weighted % | Adjusted PRRa | 95% CI | |

| Overall | 27.4 | — | — | 64.2 | — | — |

| Sex | ||||||

| Boys | 30.1 | 1.30 | 0.89–1.89 | 63.1 | 0.96 | 0.81–1.14 |

| Girls | 17.4 | 1.00 | Referent | 68.4 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Race and/or ethnicity | ||||||

| Hispanic | 15.5 | 0.89 | 0.60–1.31 | 67.7 | 1.19 | 0.99–1.42 |

| Non-Hispanic white | 30.1 | 1.00 | Referent | 62.5 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Non-Hispanic African American | 41.2 | 1.12 | 0.79–1.58 | 67.2 | 1.10 | 0.89–1.34 |

| Non-Hispanic other and/or multiracial | 21.1 | 0.90 | 0.58–1.39 | 59.9 | 0.92 | 0.71–1.19 |

| Highest level of education by parent in household | ||||||

| Less than high school | 55.5b | 1.74c | 1.17–2.59c | 49.5b | 0.64 | 0.39–1.05 |

| High school, GED, vocational | 23.4 | 0.99 | 0.67–1.47 | 75.0 | 1.10 | 0.91–1.34 |

| Some college and/or technical school | 23.8 | 0.88 | 0.61–1.26 | 63.5 | 1.00 | 0.83–1.20 |

| College degree or higher | 24.3 | 1.00 | Referent | 63.6 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Family structure | ||||||

| 2 parents, married | 24.5 | 1.00 | Referent | 64.8 | 1.00 | Referent |

| 2 parents, unmarried | 19.9b | 0.40c | 0.19–0.82c | 71.7 | 1.13 | 0.91–1.40 |

| Single mother | 37.7 | 0.88 | 0.63–1.22 | 56.1 | 0.80 | 0.63–1.02 |

| Other | 26.9 | 0.76 | 0.49–1.19 | 80.1 | 1.21 | 0.98–1.49 |

| Household poverty | ||||||

| <100% FPL | 27.6 | 1.03 | 0.57–1.84 | 68.7 | 1.08 | 0.81–1.43 |

| 100%–199% FPL | 34.3 | 1.33 | 0.77–2.27 | 58.6 | 0.98 | 0.71–1.35 |

| 200%–399% FPL | 22.5 | 1.09 | 0.73–1.63 | 64.9 | 1.00 | 0.82–1.24 |

| ≥400% FPL | 26.2 | 1.00 | Referent | 63.1 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Insurance statusd | ||||||

| Public only | 32.4 | 1.08 | 0.73–1.60 | 67.3 | 0.98 | 0.80–1.19 |

| Private only | 22.4 | 1.00 | Referent | 64.4 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Other | 24.6 | 1.03 | 0.71–1.49 | 50.2 | 0.80 | 0.62–1.03 |

| Region | ||||||

| Northeast | 26.3 | 1.41 | 0.89–2.24 | 67.5 | 1.11 | 0.88–1.41 |

| Midwest | 34.4 | 1.95c | 1.26–3.00c | 61.0 | 1.03 | 0.81–1.31 |

| South | 32.4 | 1.48 | 0.99–2.23 | 66.0 | 1.11 | 0.88–1.41 |

| West | 12.4 | 1.00 | Referent | 61.9 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Nativity | ||||||

| US born | 27.2 | 0.73 | 0.42–1.27 | 64.0 | 0.77c | 0.63–0.93c |

| Foreign born | 39.4b | 1.00 | Referent | 76.1b | 1.00 | Referent |

| Years since first diagnosise | ||||||

| 0–2 | 18.1 | 1.00 | Referent | 68.9 | 1.00 | Referent |

| 3–6 | 22.5 | 1.12 | 0.76–1.65 | 65.1 | 0.98 | 0.81–1.18 |

| ≥7 | 42.9 | 1.66c | 1.19–2.32c | 62.8 | 0.92 | 0.77–1.12 |

| Type of health care provider to give diagnosis | ||||||

| Primary care provider | 28.7 | 1.00 | Referent | 55.7 | 1.00 | Referent |

| Specialist | 24.4 | 0.82 | 0.61–1.11 | 65.7 | 1.15 | 0.89–1.49 |

| Psychologist (school and nonschool) | 23.6 | 0.70 | 0.49–1.01 | 59.7 | 1.16 | 0.90–1.51 |

| Psychiatrist | 35.2 | 1.03 | 0.74–1.44 | 69.7 | 1.18 | 0.89–1.57 |

| Other or don’t know | 34.0 | 0.70 | 0.45–1.10 | 75.3 | 1.42c | 1.10–1.84c |

| Co-occurring conditions | ||||||

| ADD and/or ADHD (ref = no ADD and/or ADHD) | 47.5 | 3.30c | 2.14–5.07c | 62.8 | 0.84c | 0.70–0.99c |

| Anxiety problems (ref = no anxiety problems) | 39.9 | 1.16 | 0.89–1.51 | 68.0 | 1.05 | 0.89–1.24 |

| Developmental delay (ref = no developmental delay) | 32.1 | 1.30 | 0.98–1.73 | 68.2 | 1.08 | 0.93–1.26 |

| Behavioral or conduct problems (ref = no behavioral or conduct problems) | 39.2 | 1.72c | 1.26–2.33c | 72.0 | 1.39c | 1.16–1.66c |

| Currently taking medication for ASD | — | — | — | 75.3 | 1.31c | 1.13–1.52c |

| Received behavioral treatment of ASD | 32.0 | 1.64c | 1.18–2.28c | — | — | — |

Data source: 2016 NSCH. GED, General Educational Development; ref, referent; —, not applicable.

Adjusted for all other demographic, sociodemographic, and birth characteristics shown.

Estimates are considered unreliable and should be used with caution. Data have a relative SE >30% or unweighted denominator n < 30.

Significant value.

Other insurance includes private, public, and unspecified.

The analyses included those with missing information on age at diagnosis (n = 95).

Approximately 64% of children with a parent-reported ASD diagnosis received behavioral treatment in the past 12 months. Children with behavioral and/or conduct problems had a higher prevalence of behavioral treatment, as well as those currently taking medications for ASD-related symptoms. US-born children or those diagnosed with ADD and/or ADHD were less likely to have received behavioral treatment.

Discussion

We used the recently released 2016 NSCH to estimate a nationally representative prevalence for children with a parent-reported ASD diagnosis of 2.50%. This is the fourth ASD prevalence report from the NSCH; however, because of several notable updates to the NSCH data collection, comparisons of the ASD prevalence estimates presented here with previously published NSCH estimates must be done cautiously because we cannot tell what proportion was explained by internal survey changes rather than external factors. The 2016 NSCH was conducted by using an address-based sample. Families responded by either mail or the Internet, whereas previous surveys were administered by telephone. In addition, question wording was changed twice. In the 2007 survey, the wording was expanded to add specificity and align with the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fourth edition.1 Also, beginning with the 2007 survey, the ASD case definition was more strictly defined on the basis of parents’ affirmative responses to 2 questions (“ever diagnosed with ASD” and “currently has ASD”) to exclude diagnoses that may have been lost because of maturation, treatment, or new information.34 Questions were also modified slightly in the 2016 NSCH to reflect changes in the most recent American Psychiatric Association criteria.1

In addition to the NSCH, population-based ASD prevalence estimates for US children have been reported from the NHIS, a nationally representative in-person household survey that includes ASD questions similar to those in the NSCH,5,9,17 and the Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network (ADDM), an ongoing surveillance system in local population-based areas in which ASD cases are identified through education and health records review.35 The most recent published NHIS ASD prevalence estimate (2.76%) is higher than that reported here but is based solely on ever receiving a diagnosis.36 The estimate of current ASD from the 2016 NHIS is 2.47%, which virtually matches the NSCH estimate reported here.37

The most recent composite ADDM prevalence estimate (1.68%), using 2014 data, was higher than the previous estimate of 1.46% using 2012 data, although this was still lower than the ASD estimate from the 2016 NSCH.35,38 Any conclusions from this latter comparison must be tempered given that estimates from these different systems reflect different years, populations (11 local US populations versus the entire United States), and ages (children aged 8 years in ADDM vs 3–17 years in NSCH).35 The estimates derived from previous versions of the NSCH and ADDM are similar when comparing overlapping years.7,39 In addition, the estimate from the NSCH falls within the range of estimates (1.31%–2.93%) from the 11 ADDM sites, and sites able to access both health and education records had higher prevalence estimates compared with sites accessing only health records.

Because there is no biological marker, ASD is a particularly challenging condition to track; thus, multiple systems with different case ascertainment strategies and supplemental data collection for children with ASD are useful in developing a full picture of ASD prevalence. Findings from the NHIS, NSCH, and ADDM each contribute unique information that, when combined, helps form a comprehensive picture of ASD among children in the United States.

Estimates reported here indicate less variation in prevalence rates across child age, race and/or ethnicity, or socioeconomic groups than observed in earlier ASD prevalence studies.7,40 Policy changes such as the 2007 AAP recommendations for universal screening by 18 to 24 months may have helped to increase ASD diagnosis among young children, thus reducing the prevalence disparity by age.41 These types of recommendations might have also had broader impacts by increasing provider and parent awareness of ASD generally, possibly contributing to increased diagnoses in traditionally underserved racial-ethnic groups. In addition, among the 87 cases of ever but not current autism, we do not know if the children achieved optimal outcomes or were initially misdiagnosed.42

The current study demonstrates that families face challenges in accessing healthcare services. Because children with ASD are likely to need multiple types of services and accompanying care coordination,43–46 the challenge of achieving a medical home appears evident among children with ASD in that they were less likely to meet the medical home criteria than other children. Although children with ASD were more likely to have a personal doctor or nurse and have a usual source for sick care, they were less likely to get needed referrals for specialty care. Consistent with previous studies, we found that children with ASD also had high rates of co-occurring mental health conditions or EBD diagnoses.21,22,35 We were not able to determine if some of the co-occurring EBD diagnoses were precursor diagnoses made as part of the diagnostic trajectory of a child receiving an ASD diagnosis versus being distinct co-occurring conditions. Nonetheless, our findings indicate that children with ASD face many developmental challenges; they particularly need referrals and care coordination.

Treatments for ASD-related symptoms have primarily been focused on behavior change and/or skill building.19 Psychotropic medications have been used to relieve some emotional and behavioral symptoms, such as challenging behaviors, irritability, anxiety, and hyperactivity.47 However, there are no pharmacologic options for treating the core deficits of ASD.48 In the current study, we found that 27% of US children with ASD took medication for ASD-related symptoms and 64% received behavioral treatment. Children with ASD who had reported diagnoses of behavioral and/or conduct problems were significantly more likely to have their ASD symptoms treated with medication and receive behavioral treatment. Children with ASD who were also reported to be diagnosed with ADD and/or ADHD were 3.30 times as likely to be treated with medication for their ASD symptoms, whereas they were only 84% as likely to receive behavioral therapy. Other studies have revealed a higher rate of psychotropic medication use for children with ASD when there was a comorbid diagnosis of ADHD.49

Our study has several strengths, including its large, nationally representative sample, which enabled examination by subgroups, and the comprehensive set of questions on ASD, co-occurring conditions, and health care experiences. However, there are also limitations. The data are cross-sectional and based on parent report of diagnoses. Undiagnosed ASD could not be assessed, so the prevalence of ASD may be underestimated, especially for younger children. Parents’ reports of diagnoses were not clinically validated; however, studies have revealed a high concordance rate (93%–98%) between parent reports of their child receiving a definite ASD diagnosis and clinician’s diagnosis in verbal children.50,51 An ASD registry in the United Kingdom revealed the reliability of parent-reported ASD diagnoses of children was 96% when compared with clinical reports.52 In addition, there was a high level of agreement between parents and clinicians on ASD-related behaviors at 12 months of age.53 However, family characteristics may affect the degree of parent-clinician agreement.54 Studies have also revealed a high test-retest reliability on maternal report of their child’s mental health conditions.55 Other studies found good agreement between parental report and pediatricians’ records,56 and fair-to-excellent agreement between parents and day care providers on recall of early symptoms associated with ASD.57 Although the specific autism diagnosis question from NHIS and NSCH has not been externally validated, the consistency of results from the NSCH, NHIS, and ADDM when compared from the same approximate period suggests a degree of reliability of these estimates.5 There is also the potential for nonresponse bias. The Census Bureau applied a nonresponse weighting adjustment that significantly mitigated any identified differential nonresponse.58 However, there could be additional sources of bias, such as selection bias, that are not controlled by the weighting adjustments. In addition, the NSCH applied poststratification adjustments to ensure that sociodemographic subgroups were appropriately represented in the estimates.

From the 2016 NSCH data, we estimated that 1 in 40 children in the United States have a parent-reported ASD diagnosis. Because ASD is a lifelong condition for most children, an important area of future research would be to study life course development and understand what factors influence health and well-being in young adulthood and beyond for these children.

Acknowledgment

We thank Alicia A. Livinski, MPH, MLS, at the National Institutes of Health Library, for her dedication and thorough library research work.

Glossary

- ADD

attention-deficit disorder

- ADDM

Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network

- ADHD

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

- ASD

autism spectrum disorder

- CI

confidence interval

- EBD

emotional, behavioral, and developmental condition

- FPL

federal poverty level

- NHIS

National Health Interview Survey

- NSCH

National Survey of Children’s Health

- PRR

prevalence rate ratio

Footnotes

Dr Kogan conceptualized and designed the study and drafted most of the initial manuscript; Dr Vladutiu conducted the data analyses and assisted with drafting of the initial manuscript; Dr Schieve assisted with drafting of the initial manuscript and provided critical review of subsequent manuscript drafts; Drs Ghandour, Blumberg, Zablotsky, Perrin, Shattuck, Kuhlthau, Harwood, and Lu provided critical reviews on all manuscript drafts; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policies of the US Department of Health and Human Services, the Health Resources and Services Administration, or the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, nor does mention of the department or agency names imply endorsement by the US government.

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: Dr Shattuck is supported by grant R01MH104423 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

COMPANION PAPER: A companion to this article can be found online at www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/peds.2018-2695.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ritvo ER, Freeman BJ, Pingree C, et al. The UCLA-University of Utah epidemiologic survey of autism: prevalence. Am J Psychiatry. 1989;146(2):194–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Naarden Braun K, Christensen D, Doernberg N, et al. Trends in the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder, cerebral palsy, hearing loss, intellectual disability, and vision impairment, metropolitan Atlanta, 1991-2010. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0124120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Newschaffer CJ, Falb MD, Gurney JG. National autism prevalence trends from United States special education data. Pediatrics. 2005;115(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/115/3/e277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Mental health in the United States: parental report of diagnosed autism in children aged 4-17 years–United States, 2003-2004. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(17):481–486 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Parner ET, Schendel DE, Thorsen P. Autism prevalence trends over time in Denmark: changes in prevalence and age at diagnosis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(12):1150–1156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kogan MD, Blumberg SJ, Schieve LA, et al. . Prevalence of parent-reported diagnosis of autism spectrum disorder among children in the US, 2007. Pediatrics. 2009;124(5):1395–1403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blumberg SJ, Bramlett MD, Kogan MD, Schieve LA, Jones JR, Lu MC. Changes in prevalence of parent-reported autism spectrum disorder in school-aged U.S. children: 2007 to 2011-2012. Natl Health Stat Report. 2013;(65):1–11 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zablotsky B, Black LI, Maenner MJ, Schieve LA, Blumberg SJ. Estimated prevalence of autism and other developmental disabilities following questionnaire changes in the 2014 National Health Interview Survey. Natl Health Stat Report. 2015;(87):1–20 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.May T, Sciberras E, Brignell A, Williams K. Autism spectrum disorder: updated prevalence and comparison of two birth cohorts in a nationally representative Australian sample. BMJ Open. 2017;7(5):e015549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim YS, Leventhal BL, Koh YJ, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders in a total population sample. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(9):904–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jensen CM, Steinhausen HC, Lauritsen MB. Time trends over 16 years in incidence-rates of autism spectrum disorders across the lifespan based on nationwide Danish register data. J Autism Dev Disord. 2014;44(8):1808–1818 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coo H, Ouellette-Kuntz H, Lloyd JE, Kasmara L, Holden JJ, Lewis ME. Trends in autism prevalence: diagnostic substitution revisited. J Autism Dev Disord. 2008;38(6):1036–1046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gal G, Abiri L, Reichenberg A, Gabis L, Gross R. Time trends in reported autism spectrum disorders in Israel, 1986-2005. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42(3):428–431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lundström S, Reichenberg A, Anckarsäter H, Lichtenstein P, Gillberg C. Autism phenotype versus registered diagnosis in Swedish children: prevalence trends over 10 years in general population samples. BMJ. 2015;350:h1961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maenner MJ, Durkin MS. Trends in the prevalence of autism on the basis of special education data. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/126/5/e1018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boyle CA, Boulet S, Schieve LA, et al. Trends in the prevalence of developmental disabilities in US children, 1997-2008. Pediatrics. 2011;127(6):1034–1042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyall K, Croen L, Daniels J, et al. The changing epidemiology of autism spectrum disorders. Annu Rev Public Health. 2017;38:81–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lai MC, Lombardo MV, Baron-Cohen S. Autism. Lancet. 2014;383(9920):896–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Mental Disorders and Disabilities Among Low-Income Children. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schieve LA, Gonzalez V, Boulet SL, et al. Concurrent medical conditions and health care use and needs among children with learning and behavioral developmental disabilities, National Health Interview Survey, 2006-2010. Res Dev Disabil. 2012;33(2):467–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levy SE, Giarelli E, Lee LC, et al. Autism spectrum disorder and co-occurring developmental, psychiatric, and medical conditions among children in multiple populations of the United States. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2010;31(4):267–275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benevides TW, Carretta HJ, Lane SJ. Unmet need for therapy among children with autism spectrum disorder: results from the 2005-2006 and 2009-2010 National Survey of Children with special health care needs. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(4):878–888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deavenport-Saman A, Lu Y, Smith K, Yin L. Do children with autism overutilize the emergency department? Examining visit urgency and subsequent hospital admissions. Matern Child Health J. 2016;20(2):306–314 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu CM, Kung PT, Li CI, Tsai WC. The difference in medical utilization and associated factors between children and adolescents with and without autism spectrum disorders. Res Dev Disabil. 2015;36C:78–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Montes G, Halterman JS. Child care problems and employment among families with preschool-aged children with autism in the United States. Pediatrics. 2008;122(1). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/122/1/e202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kogan MD, Strickland BB, Blumberg SJ, Singh GK, Perrin JM, van Dyck PC. A national profile of the health care experiences and family impact of autism spectrum disorder among children in the United States, 2005-2006. Pediatrics. 2008;122(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/122/6/e1149: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Becerra TA, Massolo ML, Yau VM, et al. A survey of parents with children on the autism spectrum: experience with services and treatments. Perm J. 2017;21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eldevik S, Hastings RP, Hughes JC, Jahr E, Eikeseth S, Cross S. Meta-analysis of early intensive behavioral intervention for children with autism. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2009;38(3):439–450 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Masi A, DeMayo MM, Glozier N, Guastella AJ. An overview of autism spectrum disorder, heterogeneity and treatment options. Neurosci Bull. 2017;33(2):183–193 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lavelle TA, Weinstein MC, Newhouse JP, Munir K, Kuhlthau KA, Prosser LA. Economic burden of childhood autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2014;133(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/133/3/e520 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Health Resources and Services Administration Frequently asked questions: 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health. Available at: https://mchb.hrsa.gov/data/national-surveys/data-user. Accessed October 19, 2017

- 33.American Academy of Pediatrics Medical Home Initiatives for Children With Special Needs Project Advisory Committee Policy statement: organizational principles to guide and define the child health care system and/or improve the health of all children. Pediatrics. 2004;113(suppl 5):1545–1547 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Blumberg SJ, Zablotsky B, Avila RM, Colpe LJ, Pringle BA, Kogan MD. Diagnosis lost: differences between children who had and who currently have an autism spectrum disorder diagnosis. Autism. 2016;20(7):783–795 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Baio J, Wiggins L, Christensen DL, et al. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years - autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2014. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2018;67(6):1–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zablotsky B, Black LI, Blumberg SJ. Estimated prevalence of children with diagnosed developmental disabilities in the United States, 2014-2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;(291):1–8 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xu G, Strathearn L, Liu B, Bao W. Prevalence of autism spectrum disorder among US children and adolescents, 2014-2016. JAMA. 2018;319(1):81–82 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christensen DL, Baio J, Van Naarden Braun K, et al. ; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) . Prevalence and characteristics of autism spectrum disorder among children aged 8 years–autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 11 sites, United States, 2012. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2016;65(3):1–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Autism and Developmental Disabilities Monitoring Network Surveillance Year 2008 Principal Investigators; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Prevalence of autism spectrum disorders–autism and developmental disabilities monitoring network, 14 sites, United States, 2008. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2012;61(3):1–19 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Durkin MS, Maenner MJ, Meaney FJ, et al. Socioeconomic inequality in the prevalence of autism spectrum disorder: evidence from a U.S. cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2010;5(7):e11551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Johnson CP, Myers SM; American Academy of Pediatrics Council on Children With Disabilities . Identification and evaluation of children with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2007;120(5):1183–1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fein D, Barton M, Eigsti IM, et al. Optimal outcome in individuals with a history of autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2013;54(2):195–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zablotsky B, Pringle BA, Colpe LJ, Kogan MD, Rice C, Blumberg SJ. Service and treatment use among children diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2015;36(2):98–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ruble LA, Heflinger CA, Renfrew JW, Saunders RC. Access and service use by children with autism spectrum disorders in Medicaid managed care. J Autism Dev Disord. 2005;35(1):3–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krauss MW, Gulley S, Sciegaj M, Wells N. Access to specialty medical care for children with mental retardation, autism, and other special health care needs. Ment Retard. 2003;41(5):329–339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Thomas KC, Ellis AR, McLaurin C, Daniels J, Morrissey JP. Access to care for autism-related services. J Autism Dev Disord. 2007;37(10):1902–1912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Accordino RE, Kidd C, Politte LC, Henry CA, McDougle CJ. Psychopharmacological interventions in autism spectrum disorder. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2016;17(7):937–952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kaplan G, McCracken JT. Psychopharmacology of autism spectrum disorders. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2012;59(1):175–187, xii [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coury DL, Anagnostou E, Manning-Courtney P, et al. Use of psychotropic medication in children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorders. Pediatrics. 2012;130(suppl 2):S69–S76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lee H, Marvin AR, Watson T, et al. Accuracy of phenotyping of autistic children based on Internet implemented parent report. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2010;153B(6):1119–1126 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Daniels AM, Rosenberg RE, Anderson C, Law JK, Marvin AR, Law PA. Verification of parent-report of child autism spectrum disorder diagnosis to a web-based autism registry. J Autism Dev Disord. 2012;42(2):257–265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Warnell F, George B, McConachie H, Johnson M, Hardy R, Parr JR. Designing and recruiting to UK autism spectrum disorder research databases: do they include representative children with valid ASD diagnoses? BMJ Open. 2015;5(9):e008625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Macari SL, Wu GC, Powell KK, Fontenelle S IV, Macris DM, Chawarska K. Do parents and clinicians agree on ratings of autism-related behaviors at 12 months of age? A study of infants at high and low risk for ASD. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(4):1069–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Neuhaus E, Beauchaine TP, Bernier RA, Webb SJ. Child and family characteristics moderate agreement between caregiver and clinician report of autism symptoms. Autism Res. 2018;11(3):476–487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kentgen LM, Klein RG, Mannuzza S, Davies M. Test-retest reliability of maternal reports of lifetime mental disorders in their children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1997;25(5):389–398 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pless CE, Pless IB. How well they remember. The accuracy of parent reports. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149(5):553–558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Larsen K, Aasland A, Diseth TH. Brief report: agreement between parents and day-care professionals on early symptoms associated with autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord. 2018;48(4):1063–1068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.U.S. Census Bureau 2016 National Survey of Children’s Health: Nonresponse Bias Analysis. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau; 2017 [Google Scholar]