Abstract

During adolescence, peer approval becomes increasingly important and may be perceived as contingent upon appearance in girls. Concurrently, girls experience hormonal changes, including an increase in progesterone. Progesterone has been implicated in affiliative behavior but inconsistently associated with body image concerns. The current study sought to examine whether progesterone may moderate the association between perceived social pressures to conform to the thin ideal and body image concerns. Secondary analyses were conducted in cross-sectional data from 813 girls in early puberty and beyond (ages 8-16) who completed assessments of the peer environment, body image concerns, and progesterone. Models for mediation and moderation were examined with BMI, age, and menarcheal status as covariates. Belief that popularity was linked to appearance and the experience of weight-related teasing were both positively associated with greater body image concerns, but neither was associated with progesterone once adjusting for covariates. Progesterone significantly interacted with perceived social pressures in predicting body image concerns. At higher progesterone levels, appearance-popularity beliefs and weight-related teasing were more strongly related to body image concerns than they were at lower progesterone levels. Findings support a moderating role for progesterone in the link between social pressures and body image concerns in girls. This study adds to a growing literature examining how girls’ hormonal environments may modulate responses to their social environments. Longitudinal and experimental work is needed to understand temporal relations and mechanisms behind these associations.

Keywords: progesterone, body image, social influence, peers, puberty

Body image concerns are prevalent in adolescence (Saunders & Frazier, 2017) and may set the stage for later problems, such as disordered eating and eating disorders, depressive symptoms, and overweight status (Goldschmidt et al., 2016; Holsen et al., 2001; Jacobi et al., 2004; Stice et al., 2002). Both social and biological changes during adolescence are theorized to contribute to these body image concerns. Peer approval and acceptance become increasingly important (Crockett et al., 1984), and peer influences are thought to play causal roles in the development of body image concerns (Thompson et al., 1999; Webb & Zimmer-Gembeck, 2014). Similarly, girls go through many physiological and hormonal changes during this time. Pubertal development is posited to play a role in body image concerns through the rapid increase of fat tissue (Halpern et al., 1999; Thompson & Chad, 2000). Additionally, puberty is marked by an increase in ovarian hormones (Lee et al., 1976). One of these hormones, progesterone, has been inconsistently associated with body image concerns (Racine, Culbert et al. 2012, Hildebrandt, Racine et al. 2015), but more consistently implicated in affiliative goals and behavior (Schultheiss, Dargel et al. 2003, Wirth, Schultheiss 2006, Maner, Miller et al. 2010). These social and hormonal changes may interact to explain individual differences in body image concerns. Thus, the current study seeks to explore how progesterone interacts with the peer environment in understanding body image concerns.

The importance of peer acceptance increases during early adolescence (Crockett et al., 1984), and adolescent girls report that appearance is an important factor in being accepted and popular (Carey et al., 2011; Crockett et al., 1984). If being thin is an important aspect of appearance and peer approval, then body image concerns will be greater for girls who experience greater peer pressure to be thin for acceptance. Supporting this assertion, body image concerns are greatest in girls who report that being thin is important for acceptance (Lieberman et al., 2001; Shroff & Thompson, 2006a) and who report increased pressures from peers to be thin (Gondoli et al., 2011; Hutchinson & Rapee, 2007; Hutchinson et al., 2010). Peer pressures to be thin also prospectively predict body image concerns (Gondoli et al., 2011; Stice & Whitenton, 2002). Weight-related teasing represents a behavioral means to communicate the importance of thinness for peer acceptance and can be conceptualized as an indicator of social rejection. Similar to peer pressure to be thin, peer teasing about weight and shape is associated with body image concerns both cross-sectionally (Hutchinson et al., 2010; Lieberman et al., 2001; Menzel et al., 2010) and longitudinally (Cattarin & Thompson, 1994; Menzel et al., 2010).

In addition to the increasing importance of peers in their social environment, adolescent girls experience numerous physiological changes during puberty, including an increase in ovarian hormones, such as progesterone (Lee et al., 1976). Experimental studies that administer progesterone suggest that progesterone may have a direct effect on affiliative behavior. Specifically, progesterone administration increases amygdala reactivity to emotion faces in humans (Van Wingen et al., 2008), and the progesterone product allopregnanolone acts in the ventral tegmental area to influence social behavior between female rats (Frye & Paris, 2011; Frye, Paris, & Rhodes, 2008). Although the relationship between progesterone and affiliation is not always replicated (Gaffey & Wirth, 2014; Gangestad & Grebe, 2017), evidence from the social psychology literature supports a potential causal link between progesterone and affiliative goals and behavior, particularly in women (Brown et al., 2009; Duffy et al., 2017; Maner et al., 2010; Schultheiss et al., 2003; Seidel et al., 2013; Wirth & Schultheiss, 2006). Studies have observed higher progesterone levels in those assigned to a task designed to increase closeness relative to a neutral social task (Brown et al., 2009). In experimental manipulations of social rejection, social rejection causes increases in progesterone (Seidel et al., 2013), with the greatest increases observed in those who are more sensitive to rejection (Maner et al., 2010). The seemingly contradictory findings of increased progesterone following closeness induction and social rejection may reflect the tendency to attempt to re-affiliate with others after rejection. Indeed, following rejection, progesterone levels are highest among those more sensitive to rejection and given the opportunity to re-affiliate compared to those who are simply rejected (Duffy et al., 2017). Finally, between-subjects differences in progesterone are associated with increased sensitivity to social stimuli (Maner & Miller, 2014), and individual differences in implicit affiliation are positively correlated with progesterone levels in women (Schultheiss et al., 2003; Wirth & Schultheiss, 2006).

Taken together, evidence supports a link between progesterone and affiliation, indicating that progesterone levels are highest in those most motivated to affiliate. As such, progesterone may play a key role in influencing susceptibility to social pressures to adhere to a cultural ideal of thinness as a means of ensuring social acceptance. Specifically, the link between perceived social importance of being thin and weight-based teasing may be more closely related to body image concerns in the presence of high versus low progesterone levels.

The current study sought to test progesterone as a moderator of the association between perceived social pressures to adhere to the thin ideal and body image concerns in adolescent girls. Specifically, we tested the hypothesis that these associations are stronger at higher progesterone levels. We focused on individual differences in the belief that thinness is important for acceptance (appearance-popularity beliefs) and peer teasing about weight and shape because both have been linked to body image concerns (Gondoli et al., 2011; Menzel et al., 2010; Shroff & Thompson, 2006a), and both relate to social acceptance or rejection by peers. Given prior theories regarding the influence of puberty on body image concerns (Killen et al., 1992; Striegel-Moore et al., 1986), we included BMI percentile, menarcheal status, and age as covariates in analyses.

Materials and Methods

Participants

Data represent a secondary analysis of 813 female twins (n=450 families)1 from the Michigan State University Twin Registry (Burt & Klump, 2013; Klump & Burt, 2006) who were enrolled in the study “Twin Study of Mood, Behavior, and Hormones during Puberty” (MBHP). Prior reports from the parent study have demonstrated that twins were representative of the broader population from which they were recruited (Burt & Klump, 2013; Klump et al., 2017; O’Connor et al., 2016). Racial and ethnic identity of those included in analyses were as follows: 79% Caucasian (n = 644), 9% African American (n = 73), and less than 1% Asian (n = 6) and American Indian or Alaska Native (n = 2). Additionally, 9% (n = 70) identified as more than one race, and 2% (n = 18) were missing data on race. Four percent of the sample identified as Hispanic (n=35); ethnicity data were missing for 1% (n = 14). Because of limited variability in progesterone prior to puberty (Elmlinger et al., 2002), only girls who were in early puberty and beyond (i.e., puberty status score 2 or above on the Pubertal Development Scale (Petersen et al., 1988)) were included in analyses. The distribution of pubertal development was as follows: 17.1% early pubertal, 41.2% mid-pubertal, 34.6% late pubertal, and 7.1% post-pubertal. Girls’ ages ranged from 8 to 16 years, mean (SD) = 12.18 (1.95) years. All twins were free from medications that may influence progesterone levels (e.g., oral contraceptive use).

Procedures

All procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. All parents provided informed consent, and all twins provided assent prior to participation. All study procedures were approved by the Michigan State University Institutional Review Board, and secondary data analyses were approved by the Florida State University Institutional Review Board. Twins came to the lab accompanied by a parent to complete questionnaire and interview assessments. Twins provided saliva samples on each of the two days before the scheduled study visit and during their in-person assessment.

Measures

Appearance-Popularity Beliefs

The Peer Attribution Scale (Lieberman et al., 2001) assessed the extent to which girls endorsed beliefs that they would be more popular and more well-liked by their friends if they were thinner and better looking. The modified version comprises four items rated on a six-point scale, ranging from “false” to “true.” These items refer to any friend rather than same-sex or opposite-sex friends (Shroff & Thompson, 2006a). Internal consistency was good in the current sample, Cronbach’s alpha = .80.

Weight-Related Teasing

History of peer teasing was assessed with the Perception of Teasing Scale for Friends, a measure adapted from the Perception of Teasing Scale (Thompson et al., 1995). The Perception of Teasing Scale for Friends consists of two items assessing history of comments and teasing from friends about appearance and weight on a five-point scale, ranging from “never” to “very often” (Shroff & Thompson, 2006b). Previous research supports its psychometric properties (Thompson et al., 2007). The Spearman Brown coefficient was .63 in this sample (Eisinga et al., 2013), supporting sufficient internal consistency.2

Progesterone

Salivary progesterone was assayed using commercially available kits (Salimetrics, Carlsbad, CA) and measured in pg/mL. Girls provided samples one and two days prior to their study visit and on the day of the visit. Samples from the three days were averaged to minimize measurement error and establish a stable estimate of individual differences in progesterone levels. The interassay CV ranged from 9.78 to 13.05. Previous research indicates comparable results between salivary and blood progesterone assessments (Edler et al., 2007). Postmenarcheal twins were scheduled during the follicular phase whenever possible to minimize the influence of ovulation on individual differences in progesterone levels. Premenarcheal twins and postmenarcheal twins with irregular menstrual periods (operationalized as missing the last two projected menstrual periods) participated without regard to menstrual cycle phase. In total, 47.8% (n=129) of postmenarcheal girls were in the menstrual or follicular phase at the time of assessment.

Body Image Concerns

Body image disturbance was assessed using a composite variable from three measures of body image concerns due to the high correlations among these conceptually related assessments and to decrease measurement error and Type 1 error: the Body Dissatisfaction subscale from the Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey (MEBS) (von Ranson et al., 2005),3 the Weight Preoccupation subscale from the MEBS, and the combined Shape Concerns and Weight Concerns subscales from the Youth Eating Disorder Examination Questionnaire (Goldschmidt et al., 2007). Scores for each variable were standardized before averaging the three scales.4 Internal consistency was good, alpha = .85.

Covariates

Height and weight were objectively measured using a scale and wall-mounted ruler and used to calculate body mass index (BMI) percentile for age and sex (Kuczmarski et al., 2000). Pubertal status was measured using the Pubertal Development Scale (Petersen et al., 1988). Girls completed four items about physical pubertal changes on a four-point scale ranging from development has not yet begun (1) to development seems complete (4). Additionally, a dichotomous item was used to assess menarche. Previous research supports the convergent validity of the self-report scale with physician assessments (Petersen et al., 1988). The Pubertal Development Scale categorical measure was used as an inclusion criterion for the present study (i.e., in early puberty or beyond). Menarcheal status was derived from the Pubertal Development Scale and used as a dichotomous covariate given evidence that progesterone increases after menarche (Lee et al., 1976) and because progesterone levels were higher in postmenarcheal girls, p < .001.5 Mothers also completed the Pubertal Development Scale, and mother report was used to fill in missing data from girls (e.g., menarcheal status) and to correct any implausible reports from girls. Mother and child reports of pubertal stage have previously show high correspondence (Laberge et al., 2001).

Statistical Analyses

Within a given family, twins were assigned as Twin 1 and Twin 2 based upon birth order. Zero-order correlations between variables were calculated within each twin set and combined using z transformations. Correlations were calculated using pairwise deletion. Moderation analyses were conducted using hierarchical linear modeling with full maximum likelihood estimates in SPSS 22.0. Individual differences in twins (Level 1) were nested within families (Level 2) to adjust for the non-independence of the twin data. All individual differences were treated as fixed effects, and the intercept was included as a random effect in models; thus, an identity matrix was used. Age, BMI percentile, and menarcheal status were included as covariates. Pubertal development was considered as an additional covariate but was rejected given its high correlations with age (r = .77) and menarcheal status (r = .85). Due to significant skew, progesterone values, Peer Attribution Scale scores, and Perception of Teasing scores were log-transformed. All predictor variables were standardized and centered prior to multilevel modeling. Interactions were probed at one standard deviation above and below the mean. The pattern of results did not differ meaningfully when using raw data or with outliers brought in; data reported in tables represent the log-transformed values.

Results

Descriptive Analyses and Bivariate Associations

Table 1 displays correlations among study variables. Age, BMI percentile, and menarcheal status were positively associated with body image concerns. Both peer attributions and teasing were positively associated with body image concerns, such that girls with stronger appearance-popularity beliefs and with a greater history of weight-related teasing had the highest body image concerns. Progesterone was positively associated with appearance-popularity beliefs, but progesterone was not associated with weight-related teasing or body image concerns. Appearance popularity beliefs were no longer associated with progesterone in a model adjusting for age, BMI percentile, and menarcheal status (p = .22).

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations, and correlations of study variables (N=789-813).

| 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Age | -- | ||||||

| 2. BMI Percentile | .06 | -- | |||||

| 3. Menarcheal Status | .74*** | .23*** | -- | ||||

| 4. Progesterone | .28*** | .02 | .27*** | -- | |||

| 5. Peer Attribution Scale | .15*** | .19*** | .15*** | .09* | -- | ||

| 6. Perception of Teasin Scale for Friends | .12*** | .09* | .12*** | .06 | .43*** | -- | |

| 7. Body Image Concerns | .13*** | .41*** | .19*** | .03 | .48*** | .37*** | -- |

| Mean/% (SD)/N |

12.18 (1.95) |

58.01 (29.78) |

41.7% (339) |

77.99 (145.87) |

6.08 (3.45) |

2.60 (1.08) |

−.001 (.88) |

Note: Means and standard deviations are from untransformed data; correlations use log-transformed values for progesterone, Peer Attribution scale, and Perception of Teasing Scale for Friends. Progesterone is measured in pg/mL; BMI = body mass index.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001;

Moderation Analyses

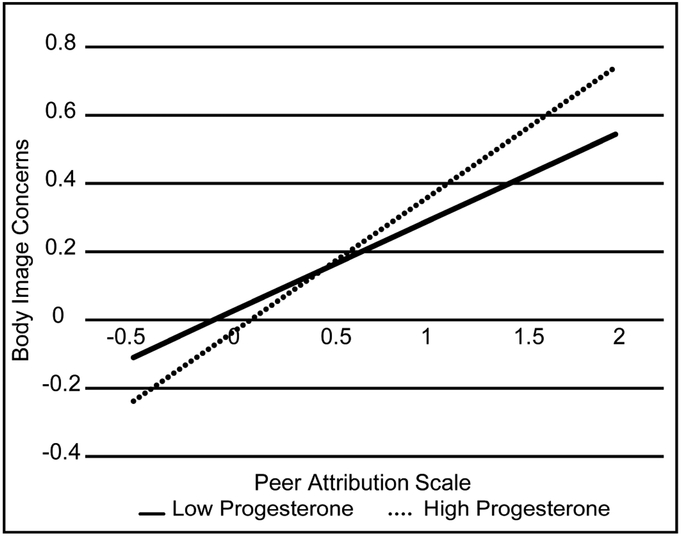

The interaction of progesterone and appearance-popularity beliefs was tested by first entering covariates, progesterone, and appearance-popularity beliefs as predictors of body image concerns as fixed effects in the multilevel model. Appearance-popularity beliefs (p < .001), but not progesterone (p = .18), were significantly positively associated with body image disturbance. With the addition of the interaction term, AIC decreased from 1644.10 to 1638.07, and BIC decreased from 1681.46 to 1680.10. Review of the likelihood-ratio test indicated that model fit improved significantly with the addition of the interaction term, X2(1) = 8.03, p = .005. The progesterone by appearance-popularity beliefs interaction was statistically significant (see Table 2). Probing the interaction revealed that at higher levels of progesterone, appearance-popularity beliefs were more strongly associated with body image concerns (Estimate = .39; SE = .03, p < .001) than at lower levels of progesterone (Estimate = .26, SE = .04, p < .001) (see Figure 1).

Table 2.

Multilevel model examining the interaction of appearance-popularity beliefs and progesterone in the cross-sectional prediction of body image concerns in girls.

| Fixed Effects | Estimate | Standard Error |

df | t | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −.19 | .12 | 779.82 | −1.63 | .10 |

| Age | .01 | .04 | 650.39 | .14 | .89 |

| BMI Percentile | .26 | .03 | 718.56 | 9.30 | < .001 |

| Menarcheal Status | .13 | .08 | 786.31 | 1.60 | .11 |

| Progesterone | −.03 | .03 | 779.84 | −1.17 | .24 |

| Appearance-Popularity Beliefs | .33 | .03 | 784.50 | 12.77 | < .001 |

| Progesterone X Appearance-Popularity Beliefs | .07 | .02 | 655.93 | 2.84 | .005 |

| Co-Variance | Estimate | Standard Error | Wald Z | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within Family | .22 | .03 | 7.56 | < .001 |

| Residual | .28 | .02 | 13.16 | < .001 |

Note: BMI = body mass index. Appearance-popularity beliefs were measured with the Peer Attribution Scale.

Figure 1.

Appearance-popularity beliefs interact with progesterone levels to cross-sectionally predict body image concerns in girls. Low and high levels of progesterone indicate the relationship between appearance-popularity beliefs and body image concerns for girls with progesterone values one standard deviation below and above the sample mean, respectively. Values represent z-scores.

In the multilevel model including covariates, progesterone, and weight-related teasing as predictors of body image concerns, weight-related teasing (p < .001), but not progesterone (p = .38), was significantly positively associated with body image concerns. With the addition of the interaction term, AIC decreased from 1727.29 to 1720.60, and BIC decreased from 1764.69 to 1762.67. Review of the likelihood-ratio test indicated that model fit improved significantly with the addition of the interaction term, X2(1) = 8.70, p = .003. The progesterone by weight-related teasing interaction was significant (see Table 3). Probing the interaction revealed that at higher levels of progesterone, teasing was more strongly associated with body image concerns (Estimate = .30; SE = .03, p < .001) than at lower levels of progesterone (Estimate = .16, SE = .04, p < .001).

Table 3.

Multilevel model examining the interaction of weight-related teasing and progesterone in the cross-sectional prediction of body image concerns in girls.

| Fixed Effects | Estimate | Standard Error |

df | t | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | −.19 | .12 | 776.45 | −1.52 | .13 |

| Age | .02 | .04 | 640.04 | .41 | .68 |

| BMI Percentile | .30 | .03 | 704.33 | 10.41 | < .001 |

| Menarcheal Status | .13 | .08 | 785.88 | 1.53 | .13 |

| Progesterone | −.02 | .03 | 778.10 | −.77 | .44 |

| Weight-Related Teasing | .23 | .03 | 780.25 | 8.80 | < .001 |

| Progesterone X Weight-Related Teasing | .07 | .02 | 667.35 | 2.96 | .003 |

| Co-Variance | Estimate | Standard Error |

Wald Z | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Within Family | .22 | .03 | 7.09 | < .001 |

| Residual | .32 | .02 | 13.11 | < .001 |

Note: BMI = body mass index. Weight-Related Teasing was measured with the scale Perception of Teasing for Friends.

Due to the moderate correlation between progesterone and age, analyses were run to determine if age, rather than progesterone, and the social environment interacted to explain body image concerns. Age did not interact with either peer popularity beliefs (p = .18) or history of weight-related teasing (p = .13) to explain body image concerns.

Discussion

The current study examined the interaction between social and physiological factors for understanding body image concerns in girls during adolescence, a period of peak risk for eating disorder onset (Smink et al., 2012). Results support a moderating role of progesterone in the relationship between the social environment and body image concerns. The highest body image concerns were observed in girls with the highest progesterone levels and greatest endorsement of social pressures to adhere to the thin ideal. We did not observe an association between progesterone and body image concerns, nor was progesterone associated with the social environment after adjusting for key covariates. This may reflect our study’s focus on individual differences in basal progesterone levels by assessing premenarcheal girls and postmenarcheal girls in the menstrual and follicular phases, when progesterone is low and relatively stable (Schumacher et al., 2014). Previous literature linking progesterone and body image concerns examined within-subject changes in progesterone across the menstrual cycle (Racine et al., 2012).

Based on prior studies implicating progesterone in affiliation motivation, progesterone may increase girls’ motivation to adhere to perceived norms required for social acceptance, making them more susceptible to the influence of these social pressures on internalization of the thin ideal. Due to the cross-sectional design, we were unable to examine temporal or causal relationships among variables. Some have hypothesized that progesterone’s association with affiliation is mediated by progesterone’s role in regulating emotions around interpersonal scenarios (Milivojevic et al., 2014); indeed, progesterone administration increases amygdala reactivity to emotion faces (Van Wingen et al., 2008). Progesterone’s metabolites may have a direct role in affiliative behavior, as subcutaneous administration of progesterone in ovariectomized mice facilitates social interaction (Koonce & Frye, 2013). This finding suggests that the peripheral progesterone measured in this study has implications for the effects of progesterone and its products in the brain and supports that progesterone may increase affiliative motivation.

The source of salivary progesterone in the current study is unknown as both the ovaries and adrenal glands secrete this hormone (Schumacher et al., 2014). Our progesterone assessment may represent a more basal assessment of adrenally-sourced progesterone given our inclusion of premenarcheal girls and efforts to sample postmenarchael girls during the menstrual or follicular phases, when progesterone levels are low (Schumacher et al., 2014). Progesterone secreted by the adrenal glands has been implicated in the stress response (Schumacher et al., 2014), and findings may reflect progesterone’s role in increasing susceptibility to a stress response in reaction to a social stressor rather than susceptibility to increased affiliative motivations (Herrera et al., 2016; Maner et al., 2010; Seidel et al., 2013; Wirth & Schultheiss, 2006). Thus, an alternative interpretation of our findings is that girls who experience more stress and/or are more stress responsive are also more sensitive to acceptance and rejection-related cues in the social environment. However, differences in progesterone are observed in experimental manipulations that do not involve rejection and are not inherently stressful (i.e., a social closeness task; Brown et al., 2009). More work is needed to understand how the link between progesterone and affiliation may be related to the stress response, affiliative motivations, or both. Indeed, motivation to gain acceptance from peers may be an adaptive means to reduce social threats and rejection.

Even at lower levels of progesterone, the social environment remained associated with body image concerns. In addition to understanding progesterone-related mechanisms, it is important to understand how girls develop appearance-popularity beliefs in order to prevent the development of body image concerns. A moderate correlation between appearance-popularity beliefs and weight-related teasing suggests that girls may develop these beliefs through experiences with teasing. These beliefs may also be learned through socialization processes, such as appearance-related conversations with friends (“fat talk”) (Sharpe et al., 2013; Tzoneva et al., 2015). Indeed, exposure to appearance-related conversations causally influences body dissatisfaction (Salk & Engeln-Maddox, 2012; Stice et al., 2003). Teaching girls to challenge unhelpful beliefs about appearance propagated by peers may help in maintaining a healthy body image. The cognitive dissonance-based Body Project provides exercises that may assist girls in critically evaluating and challenging their own beliefs and messages from peers (Becker et al., 2006; Stice et al., 2008).

The current study had several strengths that contributed to our ability to demonstrate a novel interaction between progesterone and perceived peer pressures in explaining individual differences in body image concerns. We benefited from the use of a large sample of girls across the range of pubertal development and the use of self-report and physiological assessments. We internally replicated an interaction between progesterone and peer environment using two assessments of the peer environment, importance of appearance for popularity and weight-related teasing. Moreover, findings were largely replicated when examining the individual body image scales.4 We adjusted for relevant covariates and ruled out the possibility that interactions with age, rather than progesterone, were driving findings. However, there were limitations as well. Given our reliance on secondary analyses of existing data, we were only able to examine between-subjects associations cross-sectionally. Longitudinal designs are needed to test temporal associations over the course of development, and experimental manipulations of progesterone are needed to confirm that progesterone causes changes in the strength of associations between social pressures and body image concerns. Future work should examine within subject variability in progesterone and its associations with perceptions of the social environment and body image concerns. Such analyses would extend current findings regarding who is most susceptible to peer influences to examine when they are most vulnerable. Although the overall study design sought to minimize the between subjects variability in progesterone due to menstrual cycle phase, we were unable to assess progesterone during the same part of the menstrual cycle in all postmenarcheal girls. Importantly, the pattern of results remains the same when limiting analyses among postmenarcheal girls to those in the follicular or menstrual phases at the time of data collection. Finally, we were limited to the examination of hormones that are measurable in saliva (Horvat-Gordon et al., 2005). Thus, we were unable to examine oxytocin despite its association with social behaviors such as bonding (Gangestad & Grebe, 2017). Future research should examine the interplay of oxytocin with peer influences for body image concerns, given recent evidence that oxytocin may be dysregulated in eating disorders (Culbert et al., 2016).

Taken together, the current study provides preliminary evidence that progesterone may increase vulnerability to body image concerns in response to the perceived importance of appearance for social acceptance. These findings add to a growing literature that seeks to understand individual differences in responses to ovarian hormones (Kiesner, 2017). In addition, these findings address for whom the social environment imparts the most risk. This larger question remains essential to answer, as all girls are exposed to Western ideals of thinness, but only a small minority develop clinically significant body image concerns and eating pathology. This and similar work may enhance identification of who will benefit most from interventions as well as inform the content of interventions to reduce body image concerns and risk for developing eating pathology.

Highlights.

Both the peer environment and hormones may contribute to body image concerns.

Progesterone moderates the association between peer approval and body image.

Higher progesterone levels may raise vulnerability to peer influence on body image.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Drs. Ross Crosby and Chris Schatschneider for their statistical consultation.

Funding: This work was supported by National Institute of Mental Health [R01MH092377-01 (K.L.K., S.A.B), F31MH105082 (K.J.F.)]. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute of Mental Health.

Footnotes

Declarations of Interest: None

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Because the twin design was not central to the current study, only twins who were in early puberty or beyond were included in analyses; thus, some families contributed only one twin to analyses.

Given the lower reliability of the scale, analyses were repeated using the two single items that make up the Perception of Teasing for Friends scale. The interaction results remained unchanged. Results are presented with the total scale for simplicity.

The Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey (MEBS; previously known as the Minnesota Eating Disorder Inventory [M-EDI]) was adapted and reproduced by special permission of Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc., 16204 North Florida Avenue, Lutz, Florida 33549, from the Eating Disorder Inventory (collectively, EDI and EDI-2) by Garner, Olmsted, Polivy, Copyright 1983 by Psychological Assessment Resources. Further reproduction of the MEBS is prohibited without prior permission from Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc.

We also ran analyses looking at each scale separately. The pattern of results remained unchanged when using the combined Shape Concerns and Weight Concerns subscale and Body Dissatisfaction subscale. When examining the Weigh Preoccupation subscale, the interaction between progesterone and appearance-popularity beliefs and progesterone and weight-related teasing was in the same direction but failed to reach significance, p = .26 and p = .12, respectively.

The three-way interactions between the Peer Attribution Scale, progesterone, and menarcheal status (p = .56) and between the Perception of Teasing for Friends Scale, progesterone, and menarcheal status(p = .22) did not reach statistical significance, suggesting results did not differ by menarcheal status.

References

- 1.Becker CB, Smith LM, Ciao AC, 2006. Peer-facilitated eating disorder prevention: A randomized effectiveness trial of cognitive dissonance and media advocacy. J. Couns. Psychol 53, 550–555. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown SL, Fredrickson BL, Wirth MM, Poulin MJ, Meier EA, Heaphy ED, Cohen MD, Schultheiss OC, 2009. Social closeness increases salivary progesterone in humans. Horm. Behav 56, 108–111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Burt SA, Klump KL, 2013. The Michigan State University Twin Registry (MSUTR): An update. Twin Res. Hum. Genet, 16, 344–350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carey RN, Donaghue N, Broderick P, 2011. ‘What you look like is such a big factor’: Girls’ own reflections about the appearance culture in an all-girls’ school. Fem. Psychol 21, 299–316. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cattarin JA, Thompson JK, 1994. A three-year longitudinal study of body image, eating disturbance, and general psychological functioning in adolescent females. Eat. Disord 2, 114–125. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Crockett L, Losoff M, Petersen AC, 1984. Perceptions of the peer group and friendship in early adolescence. J. Early Adolesc, 4, 155–181. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Culbert KM, Racine SE, Klump KL, 2016. Hormonal factors and disturbances in eating disorders. Curr. Psychiatry Rep 18, 1–16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Duffy KA, Harris LT, Chartrand TL, Stanton SJ, 2017. Women recovering from social rejection: The effect of the person and the situation on a hormonal mechanism of affiliation. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 76, 174–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Edler C, Lipson SF, Keel PK, 2007. Ovarian hormones and binge eating in bulimia nervosa. Psychol. Med 37, 131–141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisinga R, Te Grotenhuis M, Pelzer B, 2013. The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown? Int. J. Public Health 58, 637–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Elmlinger MW, Kühnel W, Ranke MB, 2002. Reference ranges for serum concentrations of lutropin (LH), follitropin (FSH), estradiol (E2), prolactin, progesterone, sex hormone-binding globulin (SHBG), dehydroepiandrosterone sulfate (DHEAS), cortisol and ferritin in neonates, children and young adults. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med 40, 1151–1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Frye C, Paris J, 2011. Progesterone turnover to its 5α-reduced metabolites in the ventral tegmental area of the midbrain is essential for initiating social and affective behavior and progesterone metabolism in female rats. J. Endocrinol. Invest 34, e188–e199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Frye CA, Paris JJ, Rhodes ME, 2008. Exploratory, anti-anxiety, social, and sexual behaviors of rats in behavioral estrus is attenuated with inhibition of 3α, 5α-THP formation in the midbrain ventral tegmental area. Behav. Brain Res 193, 269–276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gaffey AE, Wirth MM, 2014. Stress, rejection, and hormones: Cortisol and progesterone reactivity to laboratory speech and rejection tasks in women and men. F1000Research. 3, 208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gangestad SW, Grebe NM, 2017. Hormonal systems, human social bonding, and affiliation. Horm. Behav 91, 122–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goldschmidt AB, Doyle AC, Wilfley DE, 2007. Assessment of binge eating in overweight youth using a questionnaire version of the Child Eating Disorder Examination with instructions. Int. J. Eat. Disord 40, 460–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Goldschmidt AB, Wall M, Choo TJ, Becker C, Neumark-Sztainer D, 2016. Shared risk factors for mood-, eating-, and weight-related health outcomes. Health Psychol. 35, 245–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gondoli DM, Corning AF, Salafia EHB, Bucchianeri MM, Fitzsimmons EE, 2011. Heterosocial involvement, peer pressure for thinness, and body dissatisfaction among young adolescent girls. Body Image. 8, 143–148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Halpern CT, Udry JR, Campbell B, Suchindran C, 1999. Effects of body fat on weight concerns, dating, and sexual activity: A longitudinal analysis of black and white adolescent girls. Dev. Psychol 35, 721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Herrera AY, Nielsen SE, Mather M, 2016. Stress-induced increases in progesterone and cortisol in naturally cycling women. Neurobiol. Stress 3, 96–104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hildebrandt BA, Racine SE, Keel PK, Burt SA, Neale M, Boker S, Sisk CL, Klump KL, 2015. The effects of ovarian hormones and emotional eating on changes in weight preoccupation across the menstrual cycle. Int. J. Eat. Disord 48, 477–486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Holsen I, Kraft P, Røysamb E, 2001. The relationship between body image and depressed mood in adolescence: A 5-year longitudinal panel study. J. Health Psychol 6, 613–627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Horvat-Gordon M, Granger DA, Schwartz EB, Nelson VJ, Kivlighan KT, 2005. Oxytocin is not a valid biomarker when measured in saliva by immunoassay. Physiol. Behav 84, 445–448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hutchinson DM, Rapee RM, 2007. Do friends share similar body image and eating problems? the role of social networks and peer influences in early adolescence. Behav. Res. Ther 45, 1557–1577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hutchinson DM, Rapee RM, Taylor A, 2010. Body dissatisfaction and eating disturbances in early adolescence: A structural modeling investigation examining negative affect and peer factors. J. Early Adolesc 30, 489–517. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jacobi C, Hayward C, de Zwaan M, Kraemer HC, Agras WS, 2004. Coming to terms with risk factors for eating disorders: Application of risk terminology and suggestions for a general taxonomy. Psychol. Bull, 130, 19–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kiesner J, 2017. The menstrual cycle-response and developmental affective-risk model: A multilevel and integrative model of influence. Psychol. Rev, 124, 215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Killen JD, Hayward C, Litt I, Hammer LD, Wilson DM, Miner B, Taylor CB, Varady A, Shisslak C, 1992. Is puberty a risk factor for eating disorders? Am. J. Dis. Child 146, 323–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klump KL, Burt SA, 2006. The Michigan State University Twin Registry (MSUTR): Genetic, environmental and neurobiological influences on behavior across development. Twin Res. Hum. Genet 9, 971–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Klump KL, Culbert KM, O'Connor S, Fowler N, Burt SA, 2017. The significant effects of puberty on the genetic diathesis of binge eating in girls. Int. J. Eat. Disord 50, 984–989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koonce CJ, Frye CA, 2013. Progesterone facilitates exploration, affective and social behaviors among wildtype, but not 5α-reductase type 1 mutant, mice. Behav. Brain Res 253, 232–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kuczmarski RJ, Ogden CL, Grummer-Strawn LM, Flegal KM, Guo SS, Wei R, Mei Z, Curtin LR, Roche AF, Johnson CL, 2000. CDC growth charts: United States. Adv. Data. 314, 1–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Laberge L, Petit D, Simard C, Vitaro F, Tremblay R, Montplaisir J, 2001. Development of sleep patterns in early adolescence. J. Sleep Res 10, 59–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee PA, Xenakis T, Winer J, & Matsenbaugh S, 1976. Puberty in girls: Correlation of serum levels of gonadotropins, prolactin, androgens, estrogens, and progestins with physical changes. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab, 43, 775–784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lieberman M, Gauvin L, Bukowski WM, White DR, 2001. Interpersonal influence and disordered eating behaviors in adolescent girls: The role of peer modeling, social reinforcement, and body-related teasing. Eat. Behav 2, 215–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maner JK, Miller SL, 2014. Hormones and social monitoring: Menstrual cycle shifts in progesterone underlie women's sensitivity to social information. Evol. Hum. Behav 35, 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Maner JK, Miller SL, Schmidt NB, Eckel LA, 2010. The endocrinology of exclusion: Rejection elicits motivationally tuned changes in progesterone. Psychol. Sci 21, 581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Menzel JE, Schaefer LM, Burke NL, Mayhew LL, Brannick MT, Thompson JK, 2010. Appearance-related teasing, body dissatisfaction, and disordered eating: A meta-analysis. Body Image. 7, 261–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Milivojevic V, Sinha R, Morgan PT, Sofuoglu M, Fox HC, 2014. Effects of endogenous and exogenous progesterone on emotional intelligence in cocaine-dependent men and women who also abuse alcohol. Hum. Psychopharm. Clin. Exp 29, 589–598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O’Connor SM, Burt SA, VanHuysse JL, Klump KL, 2016. What drives the association between weight-conscious peer groups and disordered eating? Disentangling genetic and environmental selection from pure socialization effects. J. Abnorm. Psychol 125, 356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Petersen AC, Crockett L, Richards M, & Boxer A, 1988. A self-report measure of pubertal status: Reliability, validity, and initial norms. J. Youth Adolesc 17, 117–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Racine SE, Culbert KM, Keel PK, Sisk CL, Burt SA, Klump KL, 2012. Differential associations between ovarian hormones and disordered eating symptoms across the menstrual cycle in women. Int. J. Eat. Disord 45, 333–344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Salk RH, Engeln-Maddox R, 2012. Fat talk among college women is both contagious and harmful. Sex Roles. 66, 636–645. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Saunders JF, Frazier LD, 2017. Body dissatisfaction in early adolescence: The coactive roles of cognitive and sociocultural factors. J. Youth Adolesc 46, 1246–1261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schultheiss OC, Dargel A, Rohde W, 2003. Implicit motives and gonadal steroid hormones: Effects of menstrual cycle phase, oral contraceptive use, and relationship status. Horm. Beh, 43, 293–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schumacher M, Mattern C, Ghoumari A, Oudinet J, Liere P, Labombarda F, Stiruk-Ware R, de Nicola AF, Guennoun R, 2014. Revisiting the roles of progesterone and allopregnanolone in the nervous system: Resurgence of the progesterone receptors. Prog. Neurobiol 113, 6–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seidel E, Silani G, Metzler H, Thaler H, Lamm C, Gur R, Kryspin-Exner I, Habel U, Derntl B, 2013. The impact of social exclusion vs. inclusion on subjective and hormonal reactions in females and males. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 38, 2925–2932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sharpe H, Naumann U, Treasure J, Schmidt U, 2013. Is fat talking a causal risk factor for body dissatisfaction? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Eat. Disord 46, 643–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shroff H, Thompson JK, 2006a. Peer influences, body-image dissatisfaction, eating dysfunction and self-esteem in adolescent girls. J. Health Psychol 11, 533–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Shroff H, Thompson JK, 2006b. The tripartite influence model of body image and eating disturbance: A replication with adolescent girls. Body Image. 3, 17–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smink FR, Van Hoeken D, Hoek HW, 2012. Epidemiology of eating disorders: Incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Curr. Psychiatry Rep 14, 406–414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stice E, Marti CN, Spoor S, Presnell K, Shaw H, 2008. Dissonance and healthy weight eating disorder prevention programs: Long-term effects from a randomized efficacy trial. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 76, 329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stice E, Whitenton K, 2002. Risk factors for body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls: A longitudinal investigation. Dev. Psychol 38, 669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stice E, Maxfield J, Wells T, 2003. Adverse effects of social pressure to be thin on young women: An experimental investigation of the effects of "fat talk." Int. J. Eat. Disord 34, 108–117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stice E, Presnell K, Spangler D, 2002. Risk factors for binge eating onset in adolescent girls: A 2-year prospective investigation. Health Psychol. 21, 131–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Striegel-Moore RH, Silberstein LR, Rodin J, 1986. Toward an understanding of risk factors for bulimia. Am. Psychol 41, 246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Thompson AM, Chad KE, 2000. The relationship of pubertal status to body image, social physique anxiety, preoccupation with weight and nutritional status in young females. Can. J. Public Health 91, 207–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Thompson JK, Cattarin J, Fowler B, Fisher E, 1995. The Perception of Teasing Scale (POTS): A revision and extension of the Physical Appearance Related Teasing Scale (PARTS). J. Pers. Assess 65, 146–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Thompson JK, Heinberg LJ, Altabe M, Tantleff-Dunn S, 1999. Exacting beauty: Theory, assessment, and treatment of body image disturbance. American Psychological Association, Washington, D.C. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thompson JK, Shroff H, Herbozo S, Cafri G, Rodriguez J, Rodriguez M, 2007. Relations among multiple peer influences, body dissatisfaction, eating disturbance, and self-esteem: A comparison of average weight, at risk of overweight, and overweight adolescent girls. J. Pediatr. Psychol 32, 24–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tzoneva M, Forney KJ, Keel PK, 2015. The influence of gender and age on the association between “Fat-talk” and disordered eating: An examination in men and women from their 20s to their 50s. Eat. Disord 23, 439–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van Wingen G, Van Broekhoven F, Verkes R, Petersson KM, Bäckström T, Buitelaar J, Fernandez G, 2008. Progesterone selectively increases amygdala reactivity in women. Mol. Psychiatry 13, 325–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.von Ranson KM, Klump KL, lacono WG, & McGue M, 2005. The Minnesota Eating Behavior Survey: A brief measure of disordered eating attitudes and behaviors. Eat. Behav 6, 373–392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Webb HJ, Zimmer-Gembeck MJ, 2014. The role of friends and peers in adolescent body dissatisfaction: A review and critique of 15 years of research. J. Res. Adolesc 24, 564–590. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wirth MM, Schultheiss OC, 2006. Effects of affiliation arousal (hope of closeness) and affiliation stress (fear of rejection) on progesterone and cortisol. Horm. Behav 50, 786–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]