Abstract

Risk of HIV infection is high in Chinese MSM, with an annual HIV incidence ranging from 3.41 to 13.7/100 person-years. Tenofovir-based PrEP is effective in preventing HIV transmission in MSM. This study evaluates the epidemiological impact and cost-effectiveness of implementing PrEP in Chinese MSM over the next two decades. A compartmental model for HIV was used to forecast the impact of PrEP on number of infections, deaths, and disability-adjusted life years (DALY) averted. We also provide an estimate of the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) and the cost per DALY averted of the intervention. Without PrEP, there will be 1.1–3.0 million new infections and 0.7–2.3 million HIV-related deaths in the next two decades. Moderate PrEP coverage (50%) would prevent 0.17–0.32 million new HIV infections. At Truvada’s current price in China, daily oral PrEP costs $46,813–52,008 per DALY averted and is not cost-effective; on-demand Truvada reduces ICER to $25,057–27,838 per DALY averted, marginally cost-effective; daily generic tenofovir-based regimens further reduce ICER to $3675–8963, wholly cost-effective. The cost of daily oral Truvada PrEP regimen would need to be reduced by half to achieve cost-effectiveness and realize the public health good of preventing hundreds of thousands of HIV infections among MSM in China.

Keywords: PrEP, Mathematical modeling, MSM, Cost-effectiveness, China

Introduction

Despite increasing evidence of the efficacy and safety of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) using the dual combination tenofovir (TDF) and emtricitabine (FTC), China has not yet integrated PrEP into its portfolio of HIV prevention interventions and PrEP is not available in China. A highly effective biomedical prevention approach, PrEP involves people who are HIV-negative taking daily oral antiretrovials to prevent HIV acquisition. A systematic review and meta-analysis that included data from 15 randomized controlled trials and 3 real-world observational studies and demonstration projects showed that PrEP was safe and highly effective in reducing the risk of HIV infection across different populations [1]. Strong evidence across multiple studies supported the efficacy of daily oral TDF-based PrEP; only one study to date has tested an on-demand regimen, reporting an 86% reduction in HIV acquisition among highly-sexually active MSM who were randomized to “on demand” dosing as compared to those receiving placebos [2]. This review also documented that infection with drug-resistant HIV while on PrEP was very rare and most such cases occurred in individuals who started PrEP during the HIV acute infection period [1].

Globally, over 200,000 people are estimated to have initiated PrEP since approval of TDF/FTC by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2012 [3]. The promise of PrEP in combination with treatment as prevention (TasP) is starting to be visible at the population level in major urban centers in the US, Western Europe, and Australia as new diagnoses are decreasing among MSM for the first time since mandatory reporting of HIV began [4–7]. Public health authorities in 29 countries have approved the use of PrEP [8] and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the use of antiretrovirals as pre-exposure prophylaxis for “all HIV-negative individuals at substantial risk of acquiring HIV” and specified the use of tenofovir-containing PrEP regimens for any sub-population in which HIV incidence is greater than 3 per 100 person-years [9].

All available evidence indicates that incidence rates exceed 3 per 100 person-years among MSM in China, suggesting that PrEP could be a promising intervention in China. HIV prevalence among MSM is estimated at 8% nationally, with high variability reported across the country [10]. Incidence estimates from cohort, serial cross-sectional, and assay-based studies suggest that the epidemic is still in a phase of growth, with incidence rates ranging from 3.41 to 13.7/100 person-years [11–13]. Awareness of PrEP remains relatively low but increasing over time, with studies reporting PrEP awareness rates from 3 to 33% among MSM [14–16]. Studies report a wide range of willingness to use oral PrEP from 19 to 79% across different studies [14–20].

Numerous PrEP modelling and cost-effectiveness studies have been published in the literature covering a diverse range of cities and countries [21–38]. While all studies have shown that implementation of PrEP would have an epidemiological impact, its cost-effectiveness varies greatly by the assumptions driving the model and the epidemiological context. Previous modelling studies have indicated that PrEP has to target specific high-risk MSM subgroups, such as MSM with a large number of sexual partners or those with HIV+ partners, to be cost-effective [25, 27, 28, 32, 39]. In addition, PrEP cost-effectiveness in high-income countries is often worse than in low and middle-income countries. For example, the annual cost of daily oral PrEP was estimated between $9000 and 20,000 in the United States [36, 40], $8300 in the Netherlands [34], and only $525–830 in Peru [24]. Mathematical modelling has been widely used for effectiveness and cost-effectiveness evaluation in HIV programs [41, 42]. In this study, we aim to evaluate the potential population impact and cost-effectiveness of PrEP for HIV among Chinese MSM over the next two decades based on a compartmental model.

Methods

We constructed a deterministic compartmental model among Chinese MSM to forecast the HIV epidemic over the next two decades. This model simulated multiple scenarios of no intervention and various PrEP interventions among high-risk Chinese MSM (Supplementary Materials). By comparing PrEP interventions with no intervention, we predicted the number of averted infections, deaths, and DALY with the introduction of oral PrEP over a 20-year horizon. We also investigated the model’s sensitivity on epidemiologic and cost-effectiveness results based on variations in PrEP efficacy, PrEP cost and proportion of high-risk MSM.

Data Sources

We collected various parameters, including demographic, behavioral, biological, epidemiological and cost data, from published peer-reviewed articles, domestic government reports, international reports (WHO, UNAIDS), and key experts. Demographic parameters included the population size of sexually-active MSM at any given time and the number of people entering and leaving this population each year due to natural population growth. Behavioral parameters included the number of male sex partners, number of anal sex acts per partner per year, and coverage and efficacy of condoms. Biological parameters included transmission possibility of HIV per anal sex act, rate of HIV progression and mortality rates in each disease stage. Epidemiological parameters included HIV prevalence, number of new diagnoses, AIDS-related deaths, number of MSM newly-initiating ART and total number of MSM currently on ART. Cost data included drug provision, test kits for HIV and other sexually transmitted infections (STIs, syphilis, gonorrhoea and chlamydia), ART and viral load testing based on queries to infectious disease hospitals and municipal CDCs in seven urban centers in China. For indicators with multiple references, we estimated the best point estimate with lower/upper bounds, whereas for a single data value, we assumed ± 25% uncertainty (Supplementary Materials).

Population Size Estimate

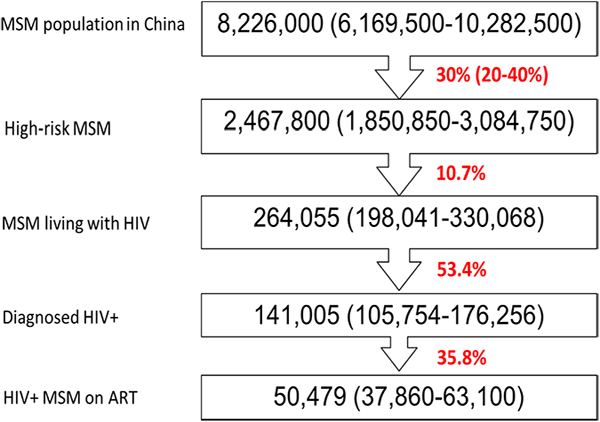

We estimated 8.2 million Chinese men as sexually-active MSM (2% of sexually-active male population) [43]. We define “high-risk MSM” as those who satisfied at least one of the following: (1) reported more than ten anal sex partners in the past 6 months; (2) reported condomless anal sex in the past 6 months; (3) diagnosed with an STI in the past 6 months. We previously estimated that approximately 20% of Chinese MSM have more than ten sex partners over the past 6 months [44] and ~ 40% of Chinese MSM did not use condom in their last sex act [45]. We therefore categorized 30% (20–40%) of Chinese MSM as “high-risk,” consistent with the percentage reported in Thailand [41]. HIV prevalence in Chinese MSM was about 8%, corresponding to 210,000 MSM living with HIV in 2016 [46]. HIV screening rate was estimated at around 53% in Chinese MSM [47, 48] and 8–20% of people living with HIV on ART were MSM [49] (Fig. 1). By excluding MSM who are already living with HIV, we estimated 2.5 million high-risk MSM were PrEP-eligible.

Fig. 1.

Population size of MSM and high-risk MSM in China, 2016

Model Construction

HIV disease progression is described in detail in Figure S1. In brief, we simulated six disease progression stages: (1) susceptible; (2) infected but undiagnosed; (3) diagnosed but untreated; (4) on 1st-line treatment; (5) treatment failure and (6) on 2nd-line treatment. HIV-infected MSM were further stratified into five CD4 categories, resulting in a total of 31 compartments representing 31 health statuses respectively. Transitions between these stages were marked by the acquisition probability, HIV screening coverage, treatment initiation rate, treatment failure rate and mortality rate, respectively (Figure S1). The compartmental model was represented as a system of differential equations (Supplementary Materials).

Probability of HIV Acquisition in MSM

We assumed that HIV is predominantly transmitted among MSM via condomless anal sex. This model does not differentiate between insertive and receptive anal sex; the per-act transmission probability is estimated as the average of the two. Probability of HIV acquisition is a function of per-act transmission probability, the number of anal sex partners, frequency of anal sex, the condom use coverage and the effectiveness of condoms. Probability of HIV acquisition is also proportional to HIV prevalence. HIV+ individuals treated with ART are considered “virally-suppressed” and do not transmit the virus [50]. The detailed expression of the function is shown in the Supplementary Materials.

Sexual Mixing in Chinese MSM

Sexual mixing between high-risk and low-risk MSM was represented by a matrix sexual “assortativity,” which described the percentage of sexual partnerships within or across risk populations [51]. The assortativity, also called “mixing index,” denoted the level of mixing and is often represented as the ratio of the sum of the off-diagonal entries in the mixing matrix and the sum of diagonal entries [52]. The mixing index approaches zero when there is no sexual mixing between the subgroups and increases to an asymptotic value when subgroups are “well-mixed.” In our model, the sexual mixing matrix satisfies three constraints: (1) overall percentage of partnerships adds up to 100% in both populations; (2) the sexual mixing index was assumed to be 0.5 to represent intermediate-mixed level of sexual contact between high-risk and low-risk MSM; (3) the number of partnerships with low-risk partners in high-risk MSM is identical to the number of partnerships with high-risk partners in low-risk MSM. This matrix was integrated in the model to calculate the number of partnerships and frequency of sexual acts within and between risk groups, which informed the probability of HIV acquisition.

Model Calibration

We sampled behavioral and epidemiological parameters between their corresponding uncertainty bounds using Latin Hypercube sampling [53]. For each created set of data, we simulated the epidemic trend and compared with collected epidemiological data. The difference between modelled prediction and actual data was measured by the sum of squared residuals, which was regarded as “goodness of fit” of the simulation [54]. The sampling and simulation procedures were repeated 1500 times; we ranked the goodness of fit in an ascending order and the top 1% of calibrated simulations were selected to represent the epidemic for further calculations and projections (Figure S2).

Epidemic Projection and Cost-Effectiveness Analysis

Based on the calibrated model, we forecast HIV epidemic trends and assessed intervention effects with multiple PrEP regimens. Our model projected the epidemic trends based on the assumption that the current behavioural and epidemio-logical parameters remained unchanged during the period of projection. The combination TDF/FTC, known by the brand name Truvada (Gilead Sciences Inc., Foster City, California), and tenofovir alone have been recommended as effective PrEP agents by the WHO; however tenofovir alone is not currently being used in any PrEP programs to our knowledge. We estimated the total PrEP cost with daily Truvada, on-demand Truvada (estimated as four times per week), daily generic TDF and daily generic TDF/lamivu-dine (3TC) (Supplementary Materials). Cost estimates were based on independent queries to seven infectious disease hospitals that prescribe Truvada, generic TDF and generic 3TC for treatment or as a component of a post-exposure prophylaxis regimen. The cost of each of these medications was equivalent across all queries due to pricing regulations for ARVs in the Chinese health system.

We assumed PrEP use between 2018 and 2037 with coverage levels of 20, 50 and 80% in high-risk MSM. Implementation of PrEP requires regular HIV and STI screening every 6 months so these testing costs were included. Limited data exists on duration and patterns of PrEP use over time. One survey on PrEP uptake and discontinuation in a US cohort of 1071 gay and bisexual men reported that among 203 participants who were on PrEP at baseline, 15% (31/203) had discontinued PrEP use at the 24-month follow-up visit [55]. In addition, it has been documented that the use of HIV prevention strategies, including PrEP, is variable over the life cycle and is likely to change based on relationship status, stage of life, substance use, immigration status, and other contextual factors [55–58]. In the absence of robust data on mean duration of use, we made an assumption that on average, an individual on PrEP will use PrEP continuously for 5 years.

We repeated the same simulation but delayed implementation initiation of PrEP to 2023. In all scenarios, we calculated HIV prevalence, number of new infections and diagnoses, HIV-related deaths, and number of MSM on ART. We compared these indicators with the status quo (no PrEP) to estimate the number of new infections, deaths and DALY averted over the next two decades due to PrEP. We used 3% as the discounting rate in our economic analysis. If the cost of each averted DALY was lower than three times the per capita gross domestic product (GDP), we deem the intervention as cost-effective [59]. In China, per-capita GDP was $8126 in 2016 [60].

We followed the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) checklist in our analysis (details in the Supplementary Materials).

Sensitivity Analysis

We included uncertainties in all epidemiological, behavioral and biological parameters. These uncertainties were reflected in the 95% confidence intervals estimated in the outcome variables (Table 1). The proportion of high-risk MSM is a key population variable, but with the least available supporting data. We conducted a sensitivity analysis on model outcomes by adjusting this proportion to 20 and 40% (Table S4–5). We also adjusted the duration of PrEP use between 2 and 10 years as part of sensitivity analysis (Table S6–7).

Table 1.

Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness analysis of PrEP among Chinese MSM during 2018–2037

| PrEP coverage in high-risk MSM | 2018–2037 | 2023–2037 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20% | 50% | 80% | 20% | 50% | 80% | |

| Investment | ||||||

| Person year of MSM covered by PrEP (× 106) | 2.3 (1.6–2.9) | 5.6 (4.1–7.2) | 9 (6.6–11.5) | 1.7 (1.2–2.2) | 4.2 (3.1–5.4) | 6.8 (4.9–8.6) |

| Number of extra HIV tests brought by PrEP (× 106) | 10 (8.4–11.5) | 24.9 (21–28.7) | 39.8 (33.7–46) | 7.5 (6.3–8.6) | 18.7 (15.8–21.6) | 29.9 (25.2–34.5) |

| Total investment cost for daily Truvada (US$, × 109) | 11.9 (8.9–14.8) | 29.6 (22.2–37.0) | 47.4 (35.6–59.3) | 9.6 (7.2–12.0) | 24.1 (18.0–30.1) | 38.5 (28.9–48.1) |

| Total investment cost for on-demand Truvada (US$, × 109) | 6.3 (4.8–7.9) | 15.9 (11.9–19.8) | 25.4 (19.0–31.7) | 5.2 (3.9–6.4) | 12.9 (9.7–16.1) | 20.6 (15.5–25.8) |

| Total investment cost with TDF (US$, × 109) | 2.7 (2.1–3.4) | 6.8 (5.1–8.5) | 10.9 (8.2–13.7) | 2.2 (1.7–2.8) | 5.5 (4.2–6.9) | 8.9 (6.7–11.1) |

| Total investment cost with TDF/3TC (US$, × 109) | 3.6 (2.7–4.5) | 9 (6.8–11.3) | 14.4 (10.8–18.0) | 2.9 (2.2–3.6) | 7.3 (5.5–9.1) | 11.7 (8.8–14.6) |

| Population impacts | ||||||

| Reduction in persons required ART (× 103) | 18.8 (3.3–26.6) | 47.9 (9.7–67.4) | 77.7 (18.2–107.2) | 10.6 (2.2–16.2) | 27.1 (6.2–41.0) | 44.1 (11.1–65.6) |

| Reduction in viral load tests required (× 103) | 5.9 (1.5–7.2) | 14.9 (4.0–18.3) | 24.1 (7–29.1) | 2.6 (0.6–3.4) | 6.5 (1.7–8.7) | 10.6 (3.0–14.0) |

| Number of infections averted (× 103) | 101.9 (69.3–130.0) | 256.2 (177.7–319.7) | 406.3 (284.9–497.5) | 66.8 (47.1–85.7) | 167.5 (117.2–206.4) | 264.5 (190.1–324.3) |

| Number of deaths averted (× 103) | 62 (38.9–73.8) | 155.1 (92.9–179.0) | 246.3 (139.8–284.2) | 34.7 (22.6–41.7) | 85.8 (54.3–101.1) | 135.7 (83.5–159.5) |

| Number of DALYs averted (× 103) | 241.5 (167.4–301.5) | 603.9 (401.9–744.1) | 969.8 (608.1–1191.8) | 142.6 (99.3–174.5) | 363.1 (239.5–442.3) | 582.5 (369.1–701.0) |

| Economic evaluation | ||||||

| Reduction in ART cost (US$, × 106) | 82 (20.8–99.4) | 211.1 (55.2–262.1) | 340.9 (97.7–417.3) | 38.1 (9.3–51.4) | 96.5 (25.7–129.5) | 156.1 (45.2–208.7) |

| Reduction in VL cost (US$, × 106) | 1 (0.2–1.2) | 2.5 (0.6–3.1) | 4.1 (1.1–4.9) | 0.4 (0.1–0.6) | 1.1 (0.3–1.5) | 1.8 (0.5–2.4) |

| Total cost reduced (US$, × 106) | 83 (21.0–100.6)a | 211.6 (55.8–265.2) | 345 (98.8–422.2) | 38.1 (9.4–52.0) | 96.2 (26.0–131.0) | 156.1 (45.7–211.1) |

| If using Daily Truvada | ||||||

| Cost required to save one infection (US$, 103) | 113.9 (107.2–120.6) | 113.3 (109.0–117.6) | 114.7 (112.0–117.4) | 137.9 (132.0–144.9) | 140.8 (136.9–144.8) | 141.1 (139.5–142.7) |

| Cost required to avert one death (US$, 103) | 201.8 (188.9–214.7) | 209848 (194.6225.1) | 217.6 (196.1–239.1) | 285.5 (270.8–300.1) | 295.8 (279.5–312.2) | 304.3 (283.5325.1) |

| Cost required to avert one DALY (US$, 103) | 48.1 (46.2–49.9) Truvada | 49.4 (46.8–52.0) | 50.9 (46.8–55.0) | 66.5 (64.8–68.3) | 67.4 (63.9–70.8) | 69 (64.5–73.5) |

| If using on-demand Truvada | ||||||

| Cost required to avert one infection (US$, 103) | 61 (57.4–64.6) | 60.6 (58.3–63.0) | 61.4 (60.0–62.8) | 73.8 (70.7–77.0) | 75.4 (73.3–77.5) | 75.5 (74.6–76.4) |

| Cost required to avert one death (US$, 103) | 108 (101.1–114.9) | 112.3 (104.1–120.5) | 116.5 (105.0–128.0) | 152.8 (145.0–160.6) | 158.4 (149.6–167.1) | 162.9 (151.8174.0) |

| Cost required to avert one DALY (US$, 103) | 25.7 (24.7–26.7) | 26.4 (25.1–27.8) | 27.2 (25.0–29.4) | 35.6 (34.7–36.6) | 36.1 (34.2–37.9) | 36.9 (34.5–39.4) |

| If using Daily TDF | ||||||

| Cost required to avert one infection (US$, 103) | 26.3 (24.7–27.8) | 26.1 (25.1–27.1) | 26.4 (25.8–27.0) | 31.8 (30.4–33.2) | 32.5 (31.6–33.4) | 32.5 (32.1–32.9) |

| Cost required to avert one death (US$, 103) | 46.5 (43.5–49.5) | 48.4 (44.9–51.9) | 50.2 (45.2–55.1) | 65.8 (62.4–69.2) | 68.2 (64.4–72.0) | 70.1 (65.4–74.9) |

| Cost required to avert one DALY (US$, 103) | 11.1 (10.6–11.5) 3TC | 11.4 (10.8–12.0) | 11.7 (10.8–12.7) | 15.3 (14.9–15.7) | 15.5 (14.7–16.3) | 15.9 (14.9–16.9) |

| If using Daily TDF/3TC | ||||||

| Cost required to avert one infection (US$, 103) | 34.6 (32.5–36.6) | 34.4 (33.1–35.7) | 34.8 (34.0–35.6) | 41.9 (40.1–43.7) | 42.8 (41.6–43.9) | 42.8 (42.3–43.3) |

| Cost required to avert one death (US$, 103) | 61.3 (57.4–65.2) | 63.7 (59.1–68.3) | 66.1 (59.5–72.6) | 86.7 (82.2–91.1) | 89.8 (84.8–94.8) | 92.4 (86.1–98.7) |

| Cost required to avert one DALY (US$, 103) | 14.6 (14.0–15.2) | 15 (14.2–15.8) | 15.4 (14.2–16.7) | 20.2 (19.7–20.7) | 20.4 (19.4–21.5) | 20.9 (19.6–22.3) |

Results

Forecasting the Epidemic Status Quo

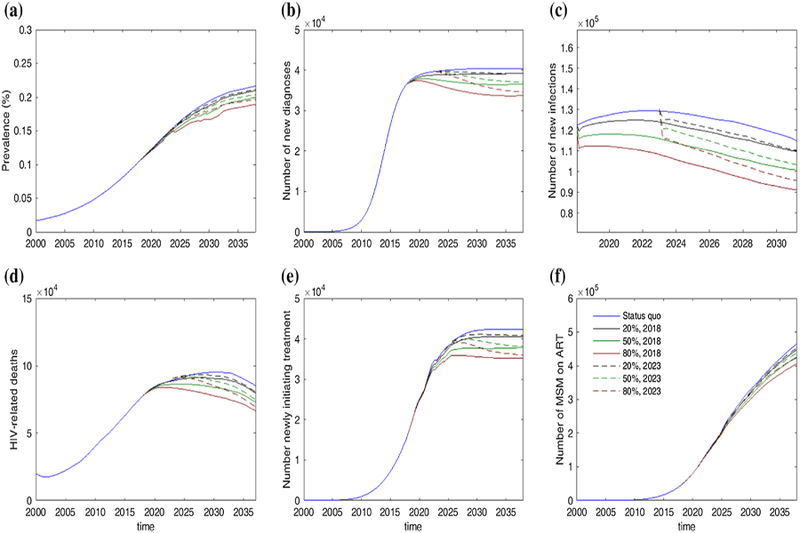

The model forecasts that in the absence of PrEP, HIV prevalence in MSM will continue to rise over the next two decades. By 2037, HIV will infect 21.6% (9.6–29.3%) of MSM in China. Cumulatively, about 2.3 (1.1–3.0) million new HIV infections would occur between 2018 and 2037. However, due to the increasing number of HIV-infected MSM initiating treatment, the number of annual HIV infections would decrease from 122,210 (65,452–146,232) in 2018 to 93,993 (68,763–110,710) in 2037. Given current rates of diagnoses and treatment initiation among MSM, the model predicts that an additional 750,091 (399,731–932,457) MSM would initiate ART over the next two decades (Fig. 2). With this epidemic trend, we forecasted a total number of 1,846,449 (703,343–2,338,973) HIV deaths and 3,331,255 (1,302,443–4,324,996) DALYs would occur over the next two decades in the absence of PrEP. This will result in a total of US $5143 (2452–6290) million HIV-related medical costs [ART cost US $4106 (1977–4997) million; viral load cost US $862 (415–1033)] million for Chinese MSM in the same period.

Fig. 2.

Projection of HIV epidemic trend among Chinese MSM from 2000 to 2037. The projective scenarios include: status quo, providing PrEP to 20, 50 and 80% high-risk starting from 2018 to starting 2023, respectively

Impacts and Cost‑Effectiveness of PrEP

An assumption of PrEP coverage of 20, 50, and 80% would enable 0.5, 1.2, and 2.0 million MSM to receive preventive intervention, respectively. Moderate coverage (50%) will reduce HIV prevalence to 19.8% (8.8–26.8%) by 2037. The model also forecasts a reduction in the number of individuals requiring ART by 38,589 (9747–67,431) and the number of person-years on ART by 202,516 (73,003–333,027). Furthermore, 248,697 (177,677–319,718) new infections, 135,916 (92,864–178,967) deaths and 572,983 (401,864–744,102) DALY would be averted over the next two decades.

Daily Truvada costs about US $3500 per person-year in China. If 50% of eligible high risk MSM initiated daily oral Truvada for an average usage period of 5 years per person, the total spending on PrEP would be US $29.6 (22.2–37.1) billion over the period from 2018 to 2037. It would cost $113,290 (108,950–117,630), 7$209,848 (194,636–225,061) and $49,410 (46,813–52,008) to avert one new HIV case, death and DALY, respectively. At this drug price, the cost required to avert one DALY is well beyond three times China’s per capita GDP ($8100 in 2016) and hence deemed not cost-effective.

On-demand Truvada (four doses per week) would cost ~ $1800 per person-year in China and $15.9 [8–19] billion over the next 20 years for the whole PrEP program. Although this would reduce the cost to avert one DALY to $26,448 ($25,057–27,838), it remains slightly above the cost-effectiveness threshold. In contrast, replacing Truvada with daily generic TDF (~ $790/person-year) or TDF/3TC (~ $1040/person-year) would reduce cost to $6.8 (5.1–8.5) and $9.0 (6.8–11.3) billion, respectively; the cost to avert one DALY would be reduced to $4529 ($3675–6805) and $5964 (4840–8963), respectively. These two scenarios were cost-effective (Table 1). We estimated that the cost of PrEP needs to be below a threshold of $1700/person-year to be cost-effective.

Impacts of Delaying PrEP Initiation to 2022

Postponing access to PrEP for MSM in China would reduce its population impacts and cost-effectiveness. Compared with “no PrEP,” delaying PrEP initiation to 2023 would still avert 167,484 (117,169–206,409) new HIV infections, 85,828 (54,325–101,131) HIV-related deaths and 363,927 (239,507–442,346) DALYs by 2037 with 50% PrEP coverage (Table 1). However, compared to immediate implementation in 2018, the delay would lead to an additional 88,726 (60,531–113,340) new infections, 69,342 (38,589–77,911) deaths and 240,813 (162,436–301,839) DALYs.

Using daily Truvada as PrEP amounted to a total PrEP spending of USD $22.6 (17.0–28.3) billion over the next 15 years. This corresponds to an ICER of $67,355 ($63,900–70,810) for each DALY averted, hence not cost-effective. Similarly, on-demand Truvada would cost $36,053 (34,204–37,903) for each DALY averted, also not cost-effective. In contrast, using daily generic TDF and TDF/3TC would only cost $15,524 ($14,728–16,320) and $20,448 ($19,399–21,497) to avert one DALY. Although the delay reduces the cost-effectiveness of the program by ~ 36%, these scenarios remained cost-effective (Table 1).

We repeated the analysis with the assumption of 20 and 40% high-risk MSM (Table S4–5) and duration of PrEP use for 2 and 5 years (Table S6–7). Changing these parameters do not change the findings for cost-effectiveness of various PrEP implementation strategies modelled.

Discussion

Tenofovir-based PrEP has gained regulatory approval in over 17 countries in the last 5 years [5]. If regulatory approval is followed by rapid implementation of PrEP through diverse service-delivery models that make sense in local health system and community contexts, it is conceivable that PrEP will have a global impact on the trajectory of the epidemic, particularly among MSM. This is the first such study focusing on China and MSM in particular, the subpopulation most affected by HIV in the country. China has already embraced TasP as a cornerstone of its HIV prevention program. However, its implementation has been uneven [49, 61] and its population-level impact has not been measured.

Our study demonstrates that the integration of PrEP into China’s national HIV prevention program could yield significant epidemiological benefits, above and beyond the impact of early treatment, as the model estimates 256,000 new infections would be averted over a twenty-year horizon if PrEP is used by 1.2 million high-risk MSM (50% PrEP coverage) for an average of 5 years each. However, the model finds that the provision of Truvada to 50% of high risk MSM over the next 20 years would not be cost effective at the current annual price of about US $3,500 in China. This lack of cost effectiveness is likely driven by two factors: the high price of Truvada in China; and the low price of the first and second line regimens currently used for treatment in China (Table S2), against which the costs of infections averted are offset in the model. The cost of Truvada would have to be cut by about 50% in order to achieve cost effectiveness for daily oral Truvada under the assumptions used in our model. With the patent on Truvada expiring in 2024 in China [62], it is likely that there will be significant price reduction in the Chinese market due to competition from generic manufacturers by 2025. Daily generic TDF alone or daily generic TDF/3TC regimen is cost effective at today’s prices. However, the efficacy of generic TDF and generic TDF/3TC regimens have not been tested in clinical trials. If these regimens are found to be efficacious in future studies conducted in China or elsewhere, such a generic regimen could be the most attractive option for a government-supported PrEP program.

Despite the lack of cost-effectiveness due to the current high price of daily oral Truvada in China, immediate widespread implementation of oral PrEP should be recommended as it has the potential to prevent hundreds of thousands of MSM from becoming infected with HIV. As shown in the model, delaying implementation by 5 years would not only decrease the cost-effectiveness but also lead to tens of thousands of infections among MSM that could be averted with immediate implementation. Implementation will require thoughtful strategies to translate this biomedical advance into population level health benefits in China. One key question will be around service delivery: how will the delivery of PrEP be organised to optimally reach those who could benefit most? Traditionally, the China CDC has been charged with delivering HIV prevention services and is experienced in collaborating with community-based organizations to provide services to healthy MSM, some of whom may engage in behaviours that elevate their risk for HIV. On the other hand, the hospital system is responsible for the care of people living with HIV. This bifurcation of HIV service delivery is similar to the US health system’s “purview paradox” [63] that came into sharp focus in the early days of PrEP implementation in the US: infectious disease practices providing services for HIV-infected patients did not see their role as providing prevention services to healthy at-risk populations, while primary care practices with no experience handling antiretroviral drugs were also reluctant to take on this work. 5 years into PrEP implementation in the US, PrEP service delivery is being piloted through: (1) infectious disease practices with traditional focus on HIV; (2) sexual health clinics; and (3) primary care practices. While each has its own strengths and weaknesses [64], PrEP service delivery should be piloted for delivery through multiple service delivery systems to identify models that could work best in different parts of China.

The costs of HIV treatment are currently borne by the Chinese government, as has been the case since the launch of the Four Frees and One Care policy in 2003 [65, 66]. However, Truvada for treatment indication has recently been made available through a government insurance plan that includes a co-pay mechanism. As policymakers start to consider the complex constellation of advantages and disadvantages of migrating treatment from the freestanding government program into the medical insurance system, they may want to consider the benefits of including coverage of PrEP as well, in the same way as statins are covered through health insurance for the prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. The Chinese government could consider other options for making Truvada available at lower costs, including price negotiations with Gilead to drop the price in the Chinese market through bulk purchasing or allowing the importation of generic TDF/FTC combinations.

Our study had several limitations. First, the model accounts for sexual mixing pattern in high- and low-risk MSM, but not the type of sexual partnerships. Frequency of condom use in commercial and casual partnerships may be different from regular partnerships. Averaging out the type of sexual partnerships may potentially over-estimate the impacts of PrEP. Second, we did not model MSM sexual contact with women as no strong epidemiological data exists on the prevalence of condomless heterosexual contact among sexually active MSM; therefore our model fails to take into account the potential preventive impact of oral PrEP on transmission to female partners of MSM. Third, we assumed uniformity of sexual risk behaviour across the lifetime, although aging is associated with reduced sexual activities and risk [67]. Our model is limited by the absence of reliable epidemiological risk data by age categories. Fourth, epidemiological and behavioral data we collected based on published studies tend to over-represent “high-risk MSM,” although we acknowledge that these are best available estimates. Fifth, the model assumes uniform 80% efficacy rate for all PrEP regimens modelled. However, demonstration projects of daily oral PrEP have reported extremely low incidence rates among PrEP users, despite continued high rates of STI [68, 69] suggesting that real world efficacy is to be likely to be higher than 90%. The model likely underestimates the effectiveness of daily Truvada. Sixth, it is likely that we underestimated the overall cost of PrEP implementation, as we did not include cost for health promotion, referral and linkage into PrEP programs or associated staffing costs. However PrEP programs could be built onto existing HIV prevention and treatment infrastructure in the health system, limiting costs of the program. Nevertheless, implementation science research that assesses service delivery models and costs associated with them is urgently needed to inform PrEP programming in China.

Despite these limitations, this modelling exercise demonstrates the effectiveness and potential cost-effectiveness of TDF-based PrEP if deployed as a public health intervention among subpopulations of MSM in China. China has the opportunity to develop innovative methods of PrEP delivery to MSM by learning from the past 5 years of HIV prevention program implementation in the US and around the globe. In doing so China stands to save money and improve health outcomes amongst those at high risk for HIV infection.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dr. Junjie Xu (The First Affiliated Hospital, China Medical University in Shenyang), Dr. Xia Li (Yunnan AIDS Care Center in Kunming), Dr. Yinzhong Shen (Shanghai Public Health Clinical Center) and Dr. Junwei Su (First Affiliated Hospital, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou) for providing pricing information for routine screening tests and costs of ARV drugs. Finally, we thank the anonymous reviewer whose insightful comments were critical to shaping the final manuscript.

Funding HW and XH contributions are supported by the Chinese Government 13th Five-Year Plan (2017ZX10201101–001–002), and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81701984). KM is supported by Grant # UL1TR001866 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health (NIH) Clinical and Translational Science Award (CTSA) program.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of interest MM receives research support in the form of grants from GSK, ViiV, Merck, and Gilead. He is a consultant to Merck and GSK and participates in the speaker bureau for Gilead Sciences. KM receives research support from a grant from GSK. No other authors report any conflict of interest.

Research Involving Human and Animal Participants This article does not contain any studies with human participants or animals performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Fonner VA, Dalglish SL, Kennedy CE, Baggaley R, O’Reilly KR, Koechlin FM, et al. Effectiveness and safety of oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis for all populations. AIDS (London, England). 2016;30(12):1973–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Molina JMCC, Charreau I, et al. , editor On demand PrEP with oral TDF/FTC in MSM: results of the ANRS Ipergay trial. In: Conference on retroviruses and opportunistic infections, Abstract 23LB; Seattle, Washington; 23–26 Feb 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Global PrEP Landscape as of April 2018. 2018. https://www.prepwatch.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/PW_Global-Tracker_Apr2018.xlsx. Accessed 6 April 2018

- 4.Wilson C Massive drop in London HIV rates may be due to internet drugs New Scientist. 2017. [updated January 9th, 2017; cited 2017 May 3rd]. https://www.newscientist.com/article/2117426-massive-drop-in-london-hiv-rates-may-be-due-to-internet-drugs/

- 5.Highleyman L San Francisco reports new low in HIV infections and faster treatment, but disparities remain www.aidsmap.com 2016. http://www.aidsmap.com/San-Francisco-reports-new-lowin-HIV-infections-and-faster-treatment-but-disparities-remain/page/3082266/. Accessed 5 Sept 2016

- 6.Smith AKJ. The Prep Effect—The Changing Landscape Of HIV Prevention In WA: Western Australia AIDS Council; 2018. http://waaids.com/item/765-the-prep-effect-the-changing-landscape-ofhiv-prevention-in-wa.html.

- 7.San Francisco Department of Public Health Population Health Division. HIV Epidemiology Annual Report 2017 San Francisco: San Francisco Department of Public Health Population Health Division; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 8.AVAC. Regulatory status of Truvada for PrEP www.avac.org2018. https://www.avac.org/sites/default/files/infographics/truvada_status_april2018.jpg.

- 9.WHO. Guideline on when to start antiretroviral therapy and on pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV. Geneva; 2015. p. 78. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qin Q, Tang W, Ge L, Li D, Mahapatra T, Wang L, et al. Changing trend of HIV, Syphilis and Hepatitis C among men who have sex with men in China. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Xu JJ, Tang WM, Zou HC, Mahapatra T, Hu QH, Fu GF, et al. High HIV incidence epidemic among men who have sex with men in china: results from a multi-site cross-sectional study. Infect Dis Poverty. 2016;5(1):82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhao T, Shi J, Chen F, Ding L, Li X, Zhang Y. Study on incidence of new HIV infection among men who have sex with men in Nanyang. Chin J AIDS STD. 2013;19:39–42. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang W, Xu JJ, Zou H, Zhang J, Wang N, Shang H. HIV incidence and associated risk factors in men who have sex with men in Mainland China: an updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Sex Health. 2016;13:373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang Y, Peng B, She Y, Liang H, Peng HB, Qian HZ, et al. Attitudes toward HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in western China. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2013;27(3):137–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhou F, Gao L, Li S, Li D, Zhang L, Fan W, et al. Willingness to accept HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among Chinese men who have sex with men. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(3):e32329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meyers K, Wu Y, Qian H, Sandfort T, Huang X, Xu J, et al. Interest in long-acting injectable PrEP in a cohort of men who have sex with men in China. AIDS Behav. 2017;1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ding Y, Yan H, Ning Z, Cai X, Yang Y, Pan R, et al. Low willingness and actual uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention among men who have sex with men in Shanghai, China. Biosci Trends. 2016;10(2):113–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang Y, Peng B, She Y, Liang H, Peng H-B, Qian H-Z, et al. Attitudes toward HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men in western China. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013;27(3):137–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang Z, Lau JTF, Fang Y, Ip M, Gross DL. Prevalence of actual uptake and willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV acquisition among men who have sex with men in Hong Kong, China. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(2):e0191671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jackson T, Huang A, Chen H, Gao X, Zhong X, Zhang Y. Cognitive, psychosocial, and sociodemographic predictors of willingness to use HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among Chinese men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(7):1853–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Desai K, Sansom SL, Ackers ML, Stewart SR, Hall HI, Hu DJ, et al. Modeling the impact of HIV chemoprophylaxis strategies among men who have sex with men in the United States: HIV infections prevented and cost-effectiveness. Aids. 2008;22(14):1829–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Paltiel AD, Freedberg KA, Scott CA, Schackman BR, Losina E, Wang B, et al. HIV preexposure prophylaxis in the United States: impact on lifetime infection risk, clinical outcomes, and cost-effectiveness. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48(6):806–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Koppenhaver RT, Sorensen SW, Farnham PG, Sansom SL. The cost-effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis in men who have sex with men in the United States: an epidemic model. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;58(2):e51–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gomez GB, Borquez A, Caceres CF, Segura ER, Grant RM, Garnett GP, et al. The potential impact of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention among men who have sex with men and trans-women in Lima, Peru: a mathematical modelling study. PLoS Med. 2012;9(10):e1001323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Juusola JL, Brandeau ML, Owens DK, Bendavid E. The Cost-effectiveness of preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2012;156(8):541–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cremin I, Alsallaq R, Dybul M, Piot P, Garnett G, Hallett TB. The new role of antiretrovirals in combination HIV prevention: a mathematical modelling analysis. Aids. 2013;27(3):447–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chen A, Dowdy DW. Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in men who have sex with men: risk calculators for real-world decision-making. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(10):e108742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schneider K, Gray RT, Wilson DP. A cost-effectiveness analysis of HIV preexposure prophylaxis for men who have sex with men in Australia. Clin Infect Dis. 2014;58(7):1027–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Drabo EF, Hay JW, Vardavas R, Wagner ZR, Sood N. A cost-effectiveness analysis of pre-exposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV among Los Angeles County men who have sex with men. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:ciw578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Glaubius RL, Hood G, Penrose KJ, Parikh UM, Mellors JW, Bendavid E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of injectable preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention in South Africa. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;63:539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jenness SM, Goodreau SM, Rosenberg E, Beylerian EN, Hoover KW, Smith DK, et al. Impact of the centers for disease control’s HIV preexposure prophylaxis guidelines for men who have sex with men in the United States. J Infect Dis. 2016;214:1800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.MacFadden DR, Tan DH, Mishra S. Optimizing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation among men who have sex with men in a large urban centre: a dynamic modelling study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):20791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mitchell KM, Prudden HJ, Washington R, Isac S, Rajaram SP, Foss AM, et al. Potential impact of pre-exposure prophylaxis for female sex workers and men who have sex with men in Bangalore, India: a mathematical modelling study. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):20942. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nichols BE, Boucher CA, van der Valk M, Rijnders BJ, van de Vijver DA. Cost-effectiveness analysis of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV-1 prevention in the Netherlands: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:1423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Punyacharoensin N, Edmunds WJ, De Angelis D, Delpech V, Hart G, Elford J, et al. Effect of pre-exposure prophylaxis and combination HIV prevention for men who have sex with men in the UK: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet HIV. 2016;3(2):e94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ross EL, Cinti SK, Hutton DW. Implementation and operational research: a cost-effective, clinically actionable strategy for targeting HIV preexposure prophylaxis to high-risk men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2016;72(3):e61–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Walensky RP, Jacobsen MM, Bekker L-G, Parker RA, Wood R, Resch SC, et al. Potential clinical and economic value of long-acting preexposure prophylaxis for South African women at high-risk for HIV infection. J Infect Dis. 2016;213(10):1523–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cremin I, McKinnon L, Kimani J, Cherutich P, Gakii G, Muriuki F, et al. PrEP for key populations in combination HIV prevention in Narobi: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet HIV. 2017;4:e214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schackman BR, Eggman AA. Cost-effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV: a review. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2012;7(6):587–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Adamson BJS, Carlson JJ, Kublin JG, Garrison LP. The potential cost-effectiveness of pre-exposure prophylaxis combined with HIV vaccines in the United States. Vaccines. 2017;5(2):13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang L, Phanuphak N, Henderson K, Nonenoy S, Srikaew S, Shattock AJ, et al. Scaling up of HIV treatment for men who have sex with men in Bangkok: a modelling and costing study. Lancet HIV. 2015;2(5):e200–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eaton JW, Menzies NA, Stover J, Cambiano V, Chindelevitch L, Cori A, et al. Health benefits, costs, and cost-effectiveness of earlier eligibility for adult antiretroviral therapy and expanded treatment coverage: a combined analysis of 12 mathematical models. Lancet Global Health. 2014;2(1):e23–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Muessig KE, Tucker JD, Wang B-X, Chen X-S. HIV and syphilis among men who have sex with men in China: the time to act is now. Sex Transm Dis. 2010;37(4):214–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhang L, Chow EP, Wilson DP. Distributions and trends in sexual behaviors and HIV incidence among men who have sex with men in China. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chow EP, Wilson DP, Zhang L. Patterns of condom use among men who have sex with men in China: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(3):653–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cai Y, Wang Z, Lau JT, Li J, Ma T, Liu Y. Prevalence and associated factors of condomless receptive anal intercourse with male clients among transgender women sex workers in Shenyang, China. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(3Suppl 2):20800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zou H, Zhang L, Chow EPF, Tang W, Wang Z. Testing for HIV/STIs in China: challenges, opportunities, and innovations. Biomed Res Int. 2017;2017:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chow EPF, Wilson DP, Zhang L. The rate of HIV testing is increasing among men who have sex with men in China. HIV Med. 2012;13(5):255–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang F, Dou Z, Ma Y, Zhang Y, Zhao Y, Zhao D, et al. Effect of earlier initiation of antiretroviral treatment and increased treatment coverage on HIV-related mortality in China: a national observational cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(7):516–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cohen Gay CL. Treatment to prevent transmission of HIV-1. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50(Supplement_3):S85–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang L, Regan DG, Chow EPF, Gambhir M, Cornelisse V, Grulich A, et al. Neisseria gonorrhoeae transmission among men who have sex with men: an anatomical site-specific mathematical model evaluating the potential preventive impact of mouthwash. Sex Transm Dis. 2017;44(10):586–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Garnett GP, Mertz KJ, Finelli L, Levine WC, St Louis ME. The transmission dynamics of gonorrhoea: modelling the reported behaviour of infected patients from Newark, New Jersey. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B. 1999;354(1384):787–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Mills HL, Riley S. The spatial resolution of epidemic peaks. PLoS Comput Biol. 2014;10(4):e1003561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van der Steen A, van Rosmalen J, Kroep S, van Hees F, Steyerberg EW, de Koning HJ, et al. Calibrating parameters for micro-simulation disease models: a review and comparison of different goodness-of-fit criteria. Med Decis Mak. 2016;36(5):652–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Whitfield THF, John SA, Rendina HJ, Grov C, Parsons JT. Why i quit pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP)? A mixed-method study exploring reasons for PrEP discontinuation and potential re-initiation among gay and bisexual men. AIDS Behav. 2018. 10.1007/s10461-018-2045-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elsesser SA, Oldenburg CE, Biello KB, Mimiaga MJ, Safren SA, Egan JE, et al. Seasons of risk: anticipated behavior on vacation and interest in episodic antiretroviral pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among a large national sample of U.S. men who have sex with men (MSM). AIDS Behav. 2016;20(7):1400–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Carlo Hojilla J, Koester KA, Cohen SE, Buchbinder S, Ladzekpo D, Matheson T, et al. Sexual behavior, risk compensation, and HIV prevention strategies among participants in the San Francisco PrEP demonstration project: a qualitative analysis of counseling notes. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(7):1461–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Underhill K, Guthrie KM, Colleran C, Calabrese SK, Operario D, Mayer KH. Temporal fluctuations in behavior, perceived HIV risk, and willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Arch Sex Behav. 2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tan-Torres T, Edejer RB, Adam T, Hutubessy R, Acharya A, Evans DB, Murray CJL. WHO guide to cost-effectiveness analysis. Geneva; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 60.WHO. GDP per capita (current US$) 2016. http://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?end=2015&locations=CN&start=1960&view=chart. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Jia Z, Mao Y, Zhang F, Ruan Y, Ma Y, Li J, et al. Antiretroviral therapy to prevent HIV transmission in serodiscordant couples in China (2003–11): a national observational cohort study. The Lancet. 2013;382(9899):1195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.MedsPaL Database. Patent Card for China 2004. http://www.medspal.org/patent/?uuid=c61535aa-76ad-4bdb-92c6-7445b24071b9.

- 63.Krakower D, Ware N, Mitty JA, Maloney K, Mayer KH. HIV providers’ perceived barriers and facilitators to implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis in care settings: a qualitative study. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(9):1712–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Marcus JL, Volk JE, Pinder J, Liu AY, Bacon O, Hare CB, et al. Successful implementation of HIV preexposure prophylaxis: lessons learned from three clinical settings. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2016;13(2):116–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Liu AY, Cohen SE, Vittinghoff E, Anderson PL, Doblecki-Lewis S, Bacon O, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for HIV infection integrated with municipal-and community-based sexual health services. JAMA Int Med. 2016;176(1):75–84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Sun X, Lu F, Wu Z, Poundstone K, Zeng G, Xu P, et al. Evolution of information-driven HIV/AIDS policies in China. Int J Epidemiol 2010;39(suppl 2):ii4–ii13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lim SH, Christen CL, Marshal MP, Stall RD, Markovic N, Kim KH, et al. Middle-aged and older men who have sex with men exhibit multiple trajectories with respect to the number of sexual partners. AIDS Behav. 2012;16(3):590–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Baral SD, Poteat T, Strömdahl S, Wirtz AL, Guadamuz TE, Beyrer C. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(3):214–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Volk JE, Marcus JL, Phengrasamy T, Blechinger D, Nguyen DP, Follansbee S, et al. No new HIV infections with increasing use of HIV preexposure prophylaxis in a clinical practice setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(10):1601–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.