Abstract

The “VA Mission Act of 2018” will expand the current “Choice Program” legislation of 2014, which has enabled outsourcing of VA care to private physicians. As the ranks of Veteran patients swell, Congress intended that the Mission Act will help relieve the VHA’s significant access problems. We contend that this new legislation will have negative consequences for veterans by diverting support from our VA system of 1300 hospitals and clinics. We recommend modification of this legislation, promoting much greater utilization of Community Health Centers (CHCs) for veterans outsourced primary care. In support of this proposal, we describe (1) features of the “VA Mission Act” relevant to outsourcing, (2) the challenges of the present “Choice Program” and likely future obstacles with the new legislation, and (3) the advantages of expanding CHC VA outsourced primary care. This policy would focus more on providing specialized care for veterans in the VA system, while coordinating with CHCs for the necessary expanded outsourced, holistic primary care. We conclude that failure to develop an incremental, cost-effective alternative as described herein represents a potential threat to adequate future support of our VA hospital system, and thus outstanding care for our veterans.

KEY WORDS: veterans, outsourced care, community health centers, primary care access, VAH care system

The “VA Mission Act of 2018”, a bipartisan Congressional effort to improve care for our veterans, was signed by President Trump on June 6, 2018. It will expand the current “Choice Program” legislation of 2014, which has enabled outsourcing of VA care to private physicians. Thus, roughly one third of all medical appointments already are outside of the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). An additional 640,000 veterans are projected to move into community care annually in the early years of the new program, as predicted by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO).1 As the ranks of Veteran patients swell, Congress intended that the Mission Act will help relieve the VHA’s significant access problems and make it easier to treat veterans.2

However, we believe that this new legislation will have negative consequences for veterans by diverting substantial support from our excellent VHA system of 1300 hospitals and clinics. We propose a modification of this legislation, promoting much greater utilization of Community Health Centers (CHCs) for veterans outsourced primary care, as first suggested in a 2014 publication.3 This would ensure high-quality, comprehensive primary care and control cost, with most subspecialty care remaining with VHA facilities.

In support of this proposal, we describe (1) features of the “VA Mission Act” relevant to outsourcing, (2) the challenges of the present “Choice Program” and likely future obstacles with the new legislation, and (3) the advantages of expanding CHC VA outsourced primary care.

Features of the VA Mission Act

Section I of Title I of this act establishes the Veteran’s Community Care Program to provide care in the community to veterans who are enrolled in the VHA system or otherwise entitled to VA care.2 Under this section, VA is required to coordinate coverage for veterans who are authorized to utilize private care, thereby ensuring that veterans do not experience a lapse in healthcare services. This section mandates access to community care if VHA does not offer care or services the veteran requires, as well as establishing multiple criteria as the basis for a veteran’s choice of community care. Payment rates for community care, to the extent practicable, are at the Medicare rate. Section 105 authorizes federally qualified CHCs to provide outsourced services for veterans. Section 403 of Title IV provides authority for VHA to pay for graduate medical education in non-VHA settings.

Challenges of Outsourcing Veterans Care

We believe that substantial obstacles will be encountered, including insufficient access to private physicians (especially in rural areas), continued conflict with private physicians regarding reimbursement issues, and uncertain quality of care from a diverse group of private physicians, not necessary focused on unique Veteran’s health issues.

About one third of veterans in the VA system now see outside doctors through the “Choice Program,” which receives $5.2 billion from the new legislation to support its final year.1, 2 This program is fragmented and unwieldy. Private doctors have complained of slow or nonexistent payments, and veterans relate that there is insurmountable red tape. In some situations, reimbursement disputes have led to legal entitlement.

The “VA Mission Act” appears to be a significant improvement. However, while facilitating expansion of veteran’s access to private healthcare, it does not provide federal money to pay for it. A bipartisan congressional effort aims to address that problem by developing a separate measure to fund the new $55 billion law. However, the president has been urging Republicans to reject the plan, instead asking Congress to pay for the new legislation by cutting spending elsewhere, in view of the current growing budget deficit. Without passage of the aforementioned modification, it is likely that difficult tradeoffs will be encountered regarding which veteran’s programs should continue to be funded. Given the new legislation’s substantial cost, a disturbing scenario is described where the VHA would be forced to cannibalize itself in order to ensure access to healthcare services via outsourcing. There is potential for funding cuts to the VHA hospital infrastructure, direct patient care, suicide prevention, medical research, and job training. Many in Congress and some veterans service organizations adamantly oppose the goal of giving veterans unlimited options to choose private doctors, arguing that such a change would starve the VHA’s excellent, vast system of government healthcare.1 There is no reliable estimate and little research that compares the cost of care inside and outside the VHA system of 1300 clinics and hospitals.

Advantages of CHC Outsourced Primary Care

We propose that Congress promote CHCs as a better solution for enhancing VA primary healthcare via outsourcing. We believe that a recent publication describing in detail the efficacy of CHC care for Medicaid patients applies equally to veterans.4 CHCs would provide our veterans with high quality, cost-effective care, with government Veterans care funds strengthening the fiscal viability of CHCs, which have received longstanding, bipartisan support.

The CHC program, now over 50 years old, has grown to include nearly 1400 health centers serving more than 26 million patients at over 9000 community sites.5 Usually, CHCs deploy interdisciplinary care teams to provide comprehensive services, including dental, vision, and behavioral health care as well as pharmaceuticals. Of particular relevance to veteran’s care, CHC integration of mental health professionals is particularly effective in managing post-traumatic stress disorders and substance use disorders. Also, excellent dental care is usually available with reduced fees for those with limited income, in contrast to the VA system, where many veterans are not eligible for dental coverage. Nearly all CHCs utilize Electronic Health Records and three in four CHCs are recognized as Patient Centered Medical Homes.

Another important factor that supports a strong partnership between the VA and CHC’s is the need to better address the health care needs of our veterans who live in rural or frontier communities. Nearly 25% of veterans live in rural areas.6, 7 The more sparsely populated a community is, the greater the challenge in providing primary care services. To rise to this challenge, HRSA historically provided funding preferences to frontier communities seeking to address geographic and other barriers to care.8 Today, 44% of all CHC’s are located in rural or frontier communities, while only 19% of the US population live in rural areas.6

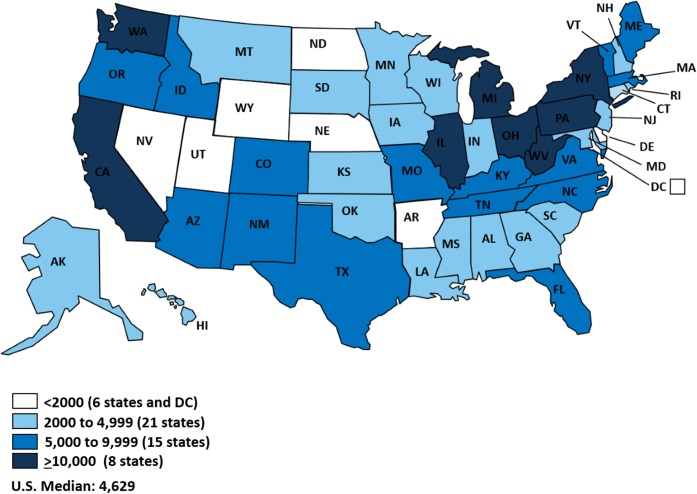

Between 2008 and 2016, the number of veterans served by CHCs increased 54% from 213,841 to 330,271.8 The number of veterans served by CHCs across the states range from 500 to over 30,000 (see Fig. 1). Although CHCs provide a wide range of services, additional revenue derived from fully reimbursed patients such as veterans is needed to expand their capacity. Of those serving veterans, approximately 87% provide mental health care, 80% provide dental health services, 29% provide substance use disorder services, and 24% provide vision care.8 Significant increases in the number of CHC’s providing substance use disorder treatment services are anticipated to result from the Health Resources and Services Administration recent announcement that it will invest “$350 million in new funding to expand access to substance use disorder and mental health services at CHCs across the nation”.9

Fig. 1.

Number of U.S. Veterans Served by Health Centers, 2016. Legend

CHCs are facing increasing difficulty in acquiring the necessary primary care provider workforce to meet desired growth. They are greatly dependent on the Teaching Health Center Graduate Medical Education (THCGME) program for the development of their workforce. This program supports new and expanded primary care medical and dental residency programs in CHC settings. At present, there are only about 60 CHCs which conduct THCGME programs, training 700 residents.10 Thus, they would represent a small percentage of CHCs caring for veterans. However, their viability is essential for the growth of CHCs in future years, thereby achieving the incremental expansion required to accommodate most of VA outsourced primary care.

THCGME programs focus training within CHCs to ensure that residents are prepared to deliver high-quality ambulatory care and have the skills they need to practice in that setting. THCGME programs implement delivery models providing primary care services that include electronic health records, attention to social determinants of health, and interdisciplinary team care.11 These programs could develop a close partnership with regional VA teaching hospitals, as a model for CHCs to utilize VAH subspecialty expertise via electronic or face-to-face consultations and thus keeping specialty care and hospitalization within the VAH system. At present, the THCGME program is struggling, despite active and widespread advocacy.4 A significant funding shortfall now prevents these training programs from pursuing future development. Insufficient funding, coupled with uncertainty regarding the program’s possible funding in the future, impedes the ability of program administrators to plan and recruit for the future. Infusion of revenue from fully reimbursed VA patients in addition to State and increased Federal and State support for trainee and faculty salary would greatly enhance their viability and facilitate their needed expansion.11

Looking Ahead

We believe that the proposed greater utilization of CHCs for VHA outsourced care would generate considerable bipartisan support and provide a high-quality, cost-effective alternative. CHCs are equipped to fulfill the unique needs of veterans while simultaneously controlling cost.11 Also, CHCs will provide better access to veterans in rural areas, where a shortage of primary care physicians continues unabated. This alternative policy would focus on providing specialized care for veterans via the VAH system, while coordinating with CHCs for the necessary expanded outsourced primary care, inclusive of oral, substance use disorder and mental health services rather than the private practice or the commercial sector where such holistic care is rarely found. As a minimal measure to achieve fiscal responsibility regarding the $55 billion “VA Mission Act”, Congress should request the Congressional Budget Office to conduct a study comparing cost and accessibility of CHC vs. private practice outsourced care.

The “VA Mission Act” involves a $55 billion 5-year commitment to addressing shortcomings in the country’s largest health system, with the potential to continue the frustrating bureaucratic and legal burdens associated with payments to private providers, as experienced with the “Choice Act.” In the absence of developing an incremental, cost-effective alternative as described herein, we believe that the private practice outsourcing provision of this legislation represents a threat to adequate future support of our excellent VA hospital system, and thus outstanding care for our veterans.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the efforts of Ms. Grace Compton in preparation of this manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Werner E, Rein L. Trump signs veterans health bill as White House works against bipartisan plan to fund it. The Washington Post. Available at: https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/trump-to-sign-veterans-heath-bill-as-white-house-works-against-plan-to-fund-it/2018/06/06/1763ac70-68d9-11e8-bf8c-f9ed2e672adf_story.html?noredirect=on&utm_term=.b3c43a836f25. Published June 6, 2018. Accessed June 7, 2018.

- 2.VA Mission Act of 2018. (VA Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks Act)

- 3.Rieselbach RE, Rockey PH, Phillips Jr. RL, Klink K, Cox M. Aligning expansion of graduate medical education with recent recommendations for reform. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161:668–669. 10.7326/M14-1838. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Rieselbach RE, Epperly T, Friedman A, et al. A new community health center/academic medicine partnership for Medicaid cost control, powered by the Mega Teaching Health Center. Academic Medicine. 2018;93(3):406–413. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shin P. The health care safety net: Community health centers’ vital role. National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation Web site. Available at: https://www.nihcm.org/categories/the-health- safety-net-community-health-centers-vital-role. Published July 2016. Accessed August 30, 2018.

- 6.Measuring America. United States Census Bureau. December 8, 2016.

- 7.Nearly one-quarter of veterans live in rural areas, Census Bureau reports. United States Census Bureau. January 25, 2017.

- 8.GW analysis of 2016 Uniform Data System, Health Resources and Services Administration.

- 9.HHS makes $350 million available to fight the opioid crisis in community health centers nationwide. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services. Available at: https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2018/06/15/hhs-makes-350-million-available-to-fight-opioid-crisis-community-health-centers.html. Accessed on August 30, 2018.

- 10.Durfey SNM, George P, Adashi EY. Permanent GME Funding for Teaching Health Centers. JAMA. 2017;317(22):2277–2278. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.5298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rieselbach RE, Epperly T, Nycz G, Rockey P. Teaching health centers can meet objectives for state Medicaid innovation. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(3):362–366. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-18-00371.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]