Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is one the most malignant cancers and has been shown to have increasing morbidity and mortality in recent years.1 Since PDAC is always diagnosed at an advanced stage, only a few patients are suitable for surgical resection. Most patients who receive chemotherapy or radiotherapy targeting pancreatic cancer do not significantly benefit from these treatments.2 Accumulating evidence has indicated that the microenvironment composed of pancreatic cancer cells and other cell types is critical in regulating tumor progression, which could serve as a therapeutic target for PDAC.3

It has been demonstrated that the stroma of PDAC is enriched with activated pancreatic stellate cells (aPSCs), which express alpha-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) and promote tumor cell proliferation and migration.4 Recently, aPSCs were reported to prevent CD8+ T cells from infiltrating tumor tissues to exert anti-tumor immunity, mediate the migration of myeloid derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) into tumor tissue and promote mast cell activation, which together lead to immune privilege in the microenvironment of PDAC and promote tumor progression.5–7 However, how aPSCs impact another major cytotoxic cell type, natural killer (NK) cells, in the stromal-rich PDAC microenvironment is not yet fully understood.

Hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) are known to have the same characteristic as PSCs and thus could serve as a good reference for PSCs. In studies of liver fibrosis, it has been found that M1 macrophages, neutrophils, T helper 17 (Th17) cells, CD8+ T cells, and natural killer T (NKT) cells can secrete proinflammatory cytokines and activate HSCs to produce collagen fibers.8–10 By contrast, some anti-fibrotic immune cells, such as M2 macrophages, regulatory T (Treg) cells, Th17 cells, NK cells, and NKT cells, inhibit HSC activation through production of IL-10 or direct killing of HSCs.11, 12 It is worth noting that NK cells play a dual role in regulating stellate cells, yet little has been reported on the role of stellate cells in regulating NK cells. In this study, we report that NK cell function is suppressed in the PDAC microenvironment, possibly by negative regulation from tumor residential aPSCs.

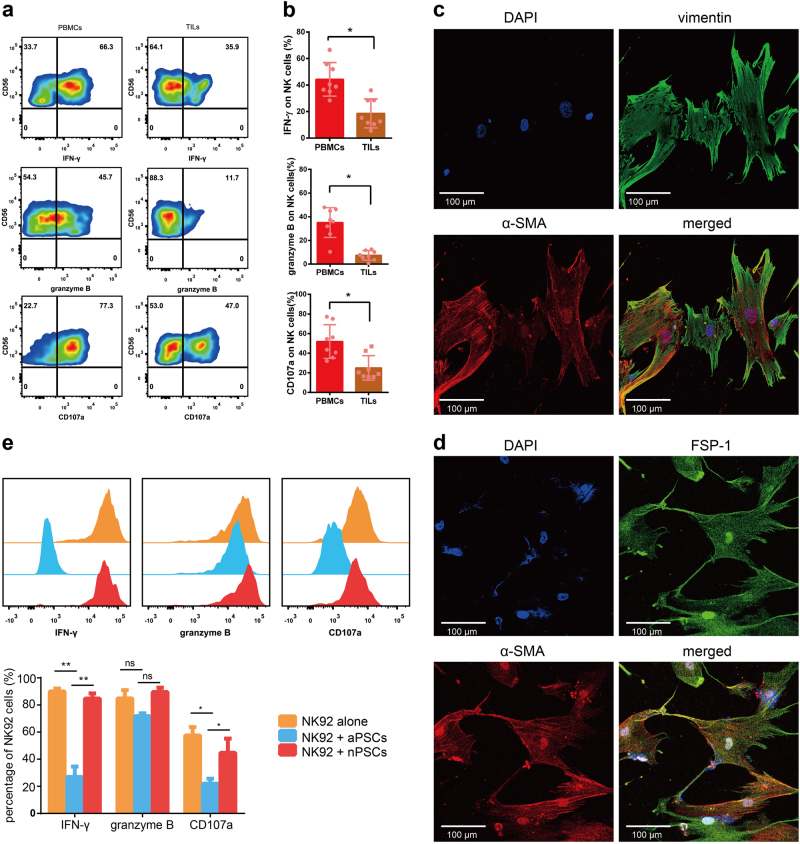

First, peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) and tissue infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) from PDAC patients were isolated and stimulated with IL-12 (10 ng/ml, R&D systems) for 18 h; then, the expression of NK function-associated proteins, including Interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), perforin, granzyme B, and CD107a, was analyzed in NK cells (CD3−CD56+ gated) by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 1a, the percentages of IFN-γ+, granzyme B+, and CD107a+ NK cells in TILs were significantly lower than those in PBMCs from the same PDAC patient. The statistical data of the patient cohort are shown in Fig. 1b. These results clearly demonstrate that NK cell function in the pancreatic cancer microenvironment is largely inhibited compared to that of NK cells in peripheral blood.

Fig. 1.

NK cells can be suppressed by aPSCs from tumor tissues of PDAC patients. a PBMCs and TILs from PDAC patients were stimulated with IL-12 for 18 h and then analyzed for IFN-γ, granzyme B, and CD107a expression in NK cells (gated on CD3−CD56+). b The percentages of IFN-γ+, granzyme B+, and CD107a+ NK cells are shown in the cumulative data (n = 8). c Immunofluorescence staining of α-SMA and vimentin expression on PSCs isolated from tumor tissue. Red indicates α-SMA, green indicates vimentin, and blue indicates DAPI. d Immunofluorescence staining of α-SMA and FSP-1 expression on PSCs isolated from tumor tissue. Red indicates α-SMA, green indicates FSP-1, and blue indicates DAPI. e NK92 cells were co-cultured with aPSCs from tumor tissues (blue lines) or quiescent nPSCs from matched noncancerous peritumor tissues (red lines) at a ratio of 1:4 for 18 h. NK92 cells alone were used as a control (orange lines). Representative plots (upper) and cumulative data (lower) of intracellular IFN-γ, granzyme B, and CD107a levels in NK92 cells by flow cytometry are shown

To investigate whether aPSCs, which are abundantly enriched in the tumor microenvironment, cross-talk with NK cells and are therefore involved in the immunomodulation of NK cells in the stroma of pancreatic cancer, we further isolated and cultured PSCs from tumor tissues of PDAC patients by two-step discontinued Percoll density gradient centrifugation. Tumor-derived PSCs showed an activated phenotype with high expression of α-SMA as well as a myofibroblast-like phenotype with vimentin and fibroblast specific protein 1 (FSP-1) expression (Fig. 1c,d).

To investigate the interactions between PSCs and NK cells, we co-cultured tumor-derived aPSCs with NK92 cells, a NK cell line with high NK functional marker (NKG2D, NKp30, NKp46) expression. As a control, we also isolated quiescent normal PSCs (nPSCs) from matched noncancerous peritumor tissues of the same patient. After NK92 cells were co-cultured with PSCs at a ratio of 1:4 for 18 h, the levels of NK cell function-associated proteins, including IFN-γ, granzyme B, and CD107a, were determined by intracellular staining via flow cytometry. The results showed that the production of IFN-γ, granzyme B, and CD107a in NK92 cells dramatically decreased in the co-culture with aPSCs compared to those in the co-culture with nPSCs and without co-culture, suggesting that tumor-derived aPSCs can suppress NK cell function and, potentially, cytotoxicity (Fig. 1e). Our data provide strong evidence that aPSCs from the pancreatic tumor stroma are different from quiescent normal PSCs in peritumor tissues, possessing a negative regulatory effect on NK cells, which could be an important contributing factor to immune suppression of NK cells that infiltrate the pancreatic cancer microenvironment.

We concluded that the abundant aPSCs found in the pancreatic tumor stroma play a role in suppressing NK cell function in the local tumor microenvironment. Further studies are underway to determine the molecular patterns of aPSC-dependent negative regulation of NK cells, which may provide new insight into the immunotherapy of PDAC.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81501354).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Qiang Huang, Email: ahslyyhq2016@163.com.

Rui Sun, Email: sunr@ustc.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2017. CA: Cancer J. Clin. 2017;67:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goess R, Friess H. A look at the progress of treating pancreatic cancer over the past 20 years. Expert Rev. Anticancer Ther. 2018;18:295–304. doi: 10.1080/14737140.2018.1428093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mace TA, Bloomston M, Lesinski GB. Pancreatic cancer-associated stellate cells: a viable target for reducing immunosuppression in the tumor microenvironment. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e24891. doi: 10.4161/onci.24891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Apte MV, et al. Desmoplastic reaction in pancreatic cancer: role of pancreatic stellate cells. Pancreas. 2004;29:179–187. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200410000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ene-Obong A, et al. Activated pancreatic stellate cells sequester CD8+ T cells to reduce their infiltration of the juxtatumoral compartment of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:1121–1132. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ma Y, Hwang RF, Logsdon CD, Ullrich SE. Dynamic mast cell-stromal cell interactions promote growth of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:3927–3937. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-4479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ren J, Hou Y, Wang T. Roles of estrogens on myeloid-derived suppressor cells in cancer and autoimmune diseases. Cell. Mol. Immunol. cmi. (2017) in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Safadi R, et al. Immune stimulation of hepatic fibrogenesis by CD8 cells and attenuation by transgenic interleukin-10 from hepatocytes. Gastroenterology. 2004;127:870–882. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2004.04.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jin Z, et al. Accelerated liver fibrosis in hepatitis B virus transgenic mice: involvement of natural killer T cells. Hepatology. 2011;53:219–229. doi: 10.1002/hep.23983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tan Z, et al. Interleukin-33 drives hepatic fibrosis through activation of hepatic stellate cells. Cell. Mol. Immunol 15, 389-399 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Manuelpillai U, et al. Human amniotic epithelial cell transplantation induces markers of alternative macrophage activation and reduces established hepatic fibrosis. PLOS One. 2012;7:e38631. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yi HS, Jeong WI. Interaction of hepatic stellate cells with diverse types of immune cells: foe or friend? J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2013;28(Suppl. 1):99–104. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]