Abstract

Background

Depression in the elderly is mainly treated by primary care physicians; the treatment is often suboptimal because of the limited resources available in primary care. New models of care in which treatment by a primary care physician is supplemented by the provision of brief, low-threshold interventions mediated by care managers are showing themselves to be a promising approach.

Methods

In this open, cluster-randomized, controlled study, we sought to determine the superiority of a model of this type over the usual form of treatment by a primary care physician. Patients in primary care aged 60 and above with moderate depressive manifestations (PHQ-9: 10–14 points) were included in the study. The primary endpoint was the percentage of patients in remission (score <5 on the Patient Health Questionnaire, PHQ-9) after the end of the intervention (12 months after baseline). The study was registered in the German Clinical Studies Registry (Deutsches Register für Klinische Studien) with the number DRKS00003589.

Results

71 primary care physicians entered 248 patients in the study, of whom 109 were in the control group and 139 in the intervention group. In an intention-to-treat analysis, the remission rate at 12 months was 25.6% (95% confidence interval [18.3; 32.8]) in the intervention group and 10.9% [5.4; 16.5]) in the control group (p = 0.004).

Conclusion

This study demonstrates the superiority of the new care model in the primary care setting in Germany, as has been found in other countries.

Depression is one of the commonest mental illnesses affecting persons aged 65 and above (whom we shall call “the elderly” in the rest of this article), with an annual prevalence of 14% (1). Approximately 10% of elderly patients in primary care have depression (2). This highly prevalent condition is clinically significant because it markedly impairs functional ability and quality of life (3), elevates mortality due to suicide (4), and worsens concomitant somatic illnesses (5).

Elderly patients with depression suffer from specific care deficits. Depression is often more difficult to diagnose in the elderly because of concomitant somatic illnesses, along with a tendency for the manifestations of depression to be somatically oriented (6, 7). The elderly rarely receive psychotherapy even when it is indicated and are less likely to be treated in accordance with the guidelines (8). The reasons for this include negative attitudes toward aging that cause patients, physicians, and psychotherapists to have low expectations for the treatability of depression, as well as lack of information, the fear that patients will be stigmatized, and inadequate network integration of physicians and psychotherapists (9, 10). Most elderly patients with depression are treated solely in primary care (11, 12). Elderly patients, like younger ones, may need psychosocial intervention (13, 14); it has been found that elderly patients are more likely to be open to receiving such kind of treatment if the diagnosis is established by a primary care physician (13).

Newer care models address these care deficits (15). One of the more successful ones is the “Improving Mood—Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment” (IMPACT) model (16), in which the depressed patient is treated in collaboration by the primary care physician, a care manager, and a supervising psychiatrist or psychotherapist. This model was developed in the USA, and studies there have shown it to be beneficial; it has since been implemented in other countries and found to be beneficial there as well (17). The model has now been adapted for use in Germany. In the GermanIMPACT study, we evaluated its effectiveness in comparison to the alternative of usual treatment.

Methods

The GermanIMPACT study was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (FKZ: 01GY1142). Before recruitment began, it was registered in the German Clinical Studies Registry (Deutsches Register für Klinische Studien) with the number DRKS00003589 and extensively described in a published study protocol (18). Consultation was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Albert-Ludwigs-Universität in Freiburg (150/12). The method of the study is described in detail in the eMethods section.

Design

The goal of the study was to compare GermanIMPACT with treatment as usual (TAU) in primary care in a cluster-randomized, controlled trial. After inclusion in the study, the participating physicians’ practices were randomly allotted to the intervention group (IG) or the control group (CG). Despite the cluster-randomized study design, the focus of the study, the intervention, and the collection of data were all centered on the individual patient. Potentially suitable patients were identified via practice software; the primary care physician determined the current severity of depressive manifestations with the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9), informed the patient about the study, and obtained his or her consent to participate in it. The relevant data for statistical evaluations were acquired by all of the study centers in uniform fashion by postal questionnaire, at baseline (t0), at 6 months (t1), and at the end of the intervention, i.e., at 12 months (t2). The study was carried out from September 2012 (start of recruitment) until August 2015 (end of all interventions).

Intervention

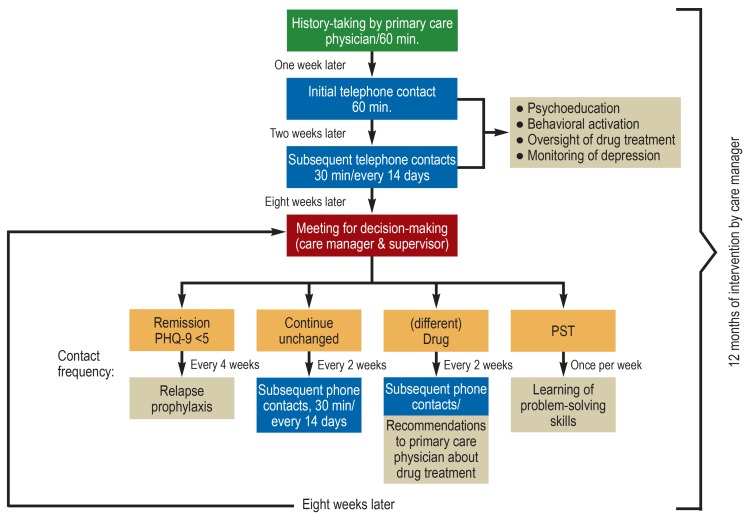

Stepwise treatment was given in the framework of the study (figure 1). It was oriented to the current condition of each patient. Treatment was provided in a collaborative effort by the primary care physician (a board-certified general practitioner or internist in primary care practice), the care manager, and the supervisor (either a physician with board certification in psychiatry and psychotherapy, or else a psychological psychotherapist).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of stepwise treatment in the GermanIMPACT study

PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; PST, problem-solving training

Green: single personal discussion at the beginning of the intervention; blue: all further telephone contacts with standard intervention; red: decision meeting taking place every eight weeks; orange: options for further treatment after the decision meeting; beige: intervention elements

The primary care physician diagnosed depression and initiated its treatment. He or she was in regular contact with the care manager to share information about the patient’s course and any necessary changes in the treatment.

A specially trained care manager (of whom there were five overall in the two centers) with years of experience in a health profession supported the treatment by staying in contact with the patient proactively and uninterruptedly. Support was given at intervals ranging from a week to a month, depending on the patient’s needs, and consisted of psychoeducation (about the symptoms and course of the disease, drugs, side effects, etc.), configuring the patient’s activities, relapse prophylaxis, and, where indicated, training in problem-solving. The initial contact took place in the doctor’s practice, and subsequent ones were conducted by telephone.

Control treatment consisted of usual treatment by the primary care physician, i.e., without any involvement of a care manager. Patients in the control group had full access to all care options of the health care system and therefore showed the usual pattern of treatment course.

There were no requirements concerning, or restrictions on, the prescription of drugs for patients in either of the arms of the study.

Recruitment of primary care practices

On the cluster level, primary care practices within a defined radius of the Freiburg and Hamburg city centers were invited to take part in the study.

Patient inclusion and exclusion criteria

Men and women with clinically diagnosed unipolar depression were included in the study. The subjects were aged 60 or older and had moderate depressive manifestations, i.e., a PHQ-9 score of 10 to 14 points (19). Patients with severe depression (>14 points) were excluded; it was recommended that they be referred for secondary (specialized) treatment as recommended by the relevant guidelines. Prerequisites to participation in the study were, in the intervention group, the subject’s ability and willingness to stay in regular personal contact with the care manager over the telephone, and, in both groups, written consent to participation in the study with a total of three written questionnaires.

Patients were excluded if they had a known substance dependency disorder or marked cognitive impairment (e.g., dementia), or if they were already in psychotherapy at the time of their recruitment. Patients with bipolar disorder, psychotic manifestations, severe behavior abnormalities, or suicidality at the time of recruitment were excluded as well.

Endpoints

The main focus of the study was the change in depressive manifestations, as measured by the PHQ-9 (19), over the duration of the study, i.e., one year. The remission of depressive manifestations at twelve months was the principal objective of treatment, and thus the primary endpoint of the study; it was operationalized as a PHQ-9 score below five points (a commonly accepted cutoff value). The secondary endpoints were: treatment response, defined as a reduction of manifestations by at least 50%; dimensional change in manifestations; health-related quality of life, as measured by the EQ-5D-3L index score (20); manifestations of anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale [GAD-7] [21]); depression-related behavior (modified from Ludman et al. [22]), problem-solving skills (modified from Bleich and Watzke, unpublished); and resilience (Resilience Scale, short form [RS-13] [23]).

Statistical analysis

In the primary, intention-to treat analysis, a mixed-effects logistic regression model was used to compare the percentage of patients in remission twelve months after the start of the intervention.

Results

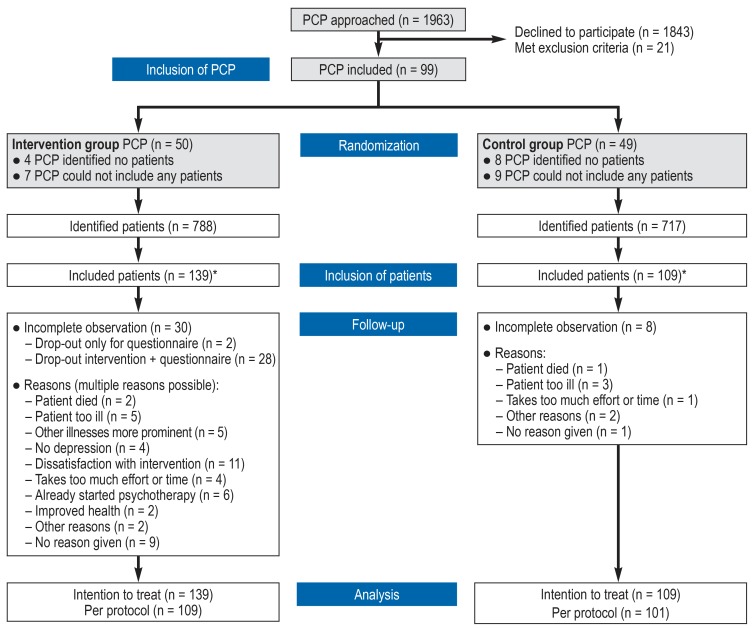

1963 primary care physicians were contacted by mail from July 2012 to November 2013. Ninety-nine agreed to participate in the study and were allotted to the intervention or the control group, according to the study design. Eighty-seven of these 99 physicians participated in the identification of potential study patients via practice software; in this way, 1505 potential subjects were identified (age and diagnosis noted in the medical record). Ultimately, 248 patients from the practices of 71 primary care physicians were included in the study, and baseline data were acquired from them. Twelve months after the start of the intervention (t2), 210 patients returned a filled-out questionnaire. Reasons for premature withdrawal from the study included changes in the significance of depressive manifestations because of altered somatic health or improved mental health, dissatisfaction with the intervention/the effort it required, or the initiation of psychotherapy. Three patients died during the course of the study for reasons unrelated to study participation (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Rectruitment of study subjects

*Reasons for non-inclusion: the patient met exclusion criteria or was not interested in participating, organizational reasons in the primary care practice

PCP, primary care physician

Description of the study sample

The mean age was 71 years (SD = 7.5 years) (table 1). Approximately 75% of the patients were women. At baseline (t0), the mean PHQ-9 score in the intervention group was 10.76 points (SD 4.1), while that in the control group was somewhat lower (9.73; SD 3.7). The percentage of patients who lived alone was higher in the intervention group (52.9%) than in the control group (38.9%).

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

|

IG (n = 139) |

CG (n = 109) |

Overall sample (n = 248) |

|

| Demographic characteristics | |||

| Age, years M (SD) Range |

71.18 (7.1) 52–88 |

71.58 (8.1) 57–92 |

71.35 (7.5) 52–92 |

| Baseline T0 (PHQ-9) M (SD) Range |

10.78 (4.1) 1–22 |

9.73 (3.7) 2–22 |

10.32 (3.9) 1–22 |

| Sex; n (%) Female |

107 (77.0) |

85 (78.0) |

192 (77.4) |

| Living situation Living alone, n (%) |

73 (52.9) |

42 (38.9) |

115 (46.7) |

IG, intervention group; CG, control group; n, number; M, mean; SD, standard deviation

Results: primary endpoint

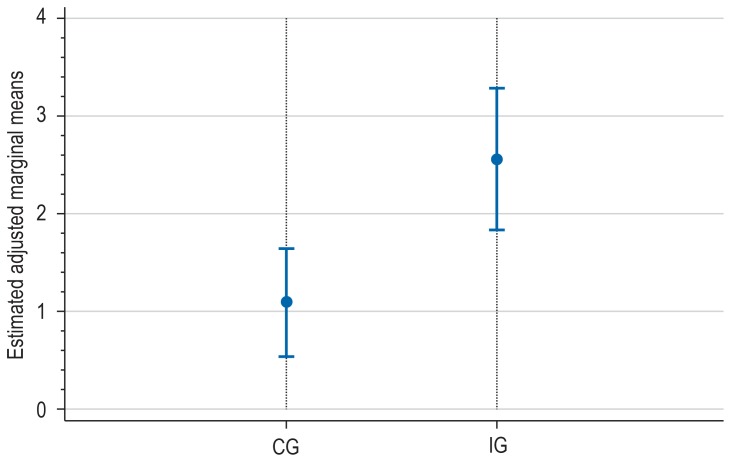

The adjusted and estimated remission rate in the intervention group was 25.6% (95% confidence interval, [18.3; 32.8]). This was significantly (p = 0.004) higher than the corresponding value in the control group, which was 10.9% [5.4; 16.5]) (Table 2, Figure 3).

Table 2. Results of the intention-to-treat analyses.

| Endpoints |

Adjusted marginal means, IG [95% confidence interval] |

Adjusted marginal means, CG [95% confidence interval] |

P-value |

| PHQ-9 remission (<5) | 0.26 [0.183; 0.328] |

0.11 [0.054; 0.165] |

0.004* |

| PHQ-9 response (50% reduction) | 0.23 [0.146; 0.305] |

0.11 [0.041; 0.169] |

0.029* |

| PHQ-9 dimensional | 8.13 [7.42; 8.85] |

9.38 [8.79; 9.96] |

0.009* |

| GAD7 | 6.75 [6.05; 7.45] |

7.15 [6.61; 7.70] |

0.38 |

| Depression-related behavior | 3.02 [2.83; 3.21] |

2.97 [2.79; 3.14] |

0.67 |

| RS–13 | 59.25 [57.11; 61.40] |

59.34 [57.27; 61.41] |

0.96 |

| PSS | 15.94 [15.45; 16.42] |

15.58 [15.14; 16.02] |

0.29 |

| EQ-5D Index | 0.57 [0.52; 0.61] |

0.66 [0.61; 0.70] |

0.005* |

* significant difference between the intervention group and the control group. IG, intervention group; CG, control group; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale; RS-13, Resilience Scale (short form); PSS, problem-solving skills; EQ-5D-3L, questionnaire on health-related quality of life

Figure 3.

Remission on follow-up at 12 month (Patient Health Questionnaire; PHQ-9) CG, control group; IG, intervention group; adjusted marginal means with 95% confidence intervals

Results: secondary endpoints

The rate of response to treatment was higher in the intervention group (22.5% [14.6; 30.5]) than in the control group (10.5% [4.1; 16.9]; p = 0.029). On the level of the estimated mean, lower depressivity scores were found in the intervention group (8.13; [7.42; 8.85]) than in the control group (9.38; [8.79; 9.96]; p = 0.009). The intervention had an effect on quality of life as well (EQ-5D-3L index score, p = 0.005). The adjusted estimated mean value was 0.66 [0.61; 0.70] in the intervention group and 0.57 ([0.52; 0.61]; p = 0.005) in the control group, on a scale from 0 (very poor) to 1 (best possible). Only very slight differences were seen in general manifestations of anxiety, depression-related behavior, individual mental resilience, and problem-solving skills (table 2).

Sensitivity analyses

In the framework of a sensitivity analysis, a per-protocol analysis was additionally computed, in order to investigate the stability of the findings. This analysis revealed the findings to be highly consistent (etable 1).

eTable 1. Results of the per-protocol analyses.

| Endpoints |

Adj. marginal means, IG [95% confidence interval] |

Adj. marginal means, CG [95% confidence interval] |

P-value |

| PHQ-9 remission (<5) | 0.241 [0.155; 0.326] |

0.111 [0.048; 0.174] |

0.023* |

| PHQ-9 response (50% reduction) | 0.225 [0.131; 0.319] |

0.108 [0.036; 0.180] |

0.059 |

| PHQ-9 dimensional | 8.109 [7.25; 8.97] |

9.282 [8.71; 7.25] |

0.026* |

| GAD7 | 6.722 [5.94; 7.50] |

6.939 [6.33; 7.55] |

0.670 |

| Depression-related behavior | 3.020 [2.79; 3.25] |

2.986 [2.81; 3.17] |

0.820 |

| RS–13 | 59.204 [56.89; 61.51] |

59.622 [57.43; 61.81] |

0.798 |

| PSS | 16.163 [15.71; 16.62] |

15.635 [15.15; 16.12] |

0.120 |

| EQ-5D Index | 0.61 [0.57; 0.65] |

0.56 [0.51; 0.60] |

0.102 |

Analyses based on n = 210; * significant difference between the intervention group and the control group

Adj., adjusted; IG, intervention group; CG, control group; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale;

RS-13, Resilience Scale (short form); PSS, problem-solving skills; EQ-5D-3L, questionnaire on health-related quality of life

Additional analyses of possible differences in treatment revealed that, at all measurement timepoints, approximately half of all patients were being treated with psychoactive drugs. At no timepoint did the two groups differ significantly in this regard (etable 2). Further analyses of utilization will be carried out as part of the planned health-economic analyses.

eTable 2. Percentage of patients taking psychoactive drugs.

|

IG (n = 139) |

CG (n = 109) |

P-value | |

| At T0 (%, SE) | 53.96% (4.24%) | 54.13% (4.79%) | 0.979 |

| At T1 (%, SE) | 58.14% (4.67%) | 46.02% (4.92%) | 0.073 |

| At T2 (%, SE) | 53.77% (4.71%) | 47.52% (4.93%) | 0.362 |

Analyses based on n = 248, data replacement by multiple imputation;

IG, intervention group; CG, control group; SE, standard error

Discussion

In the GermanIMPACT study, the effects of a collaborative approach to the treatment of depression in elderly patients in primary care were studied in a cluster-randomized, controlled trial in comparison to usual treatment. One year after the beginning of treatment, the remission rate in the intervention group was approximately twice as high as in the control group. There was thus a statistically significant and clinically relevant effect on the primary endpoint of the study.

The study was designed according to high scientific standards and was carried out in typical settings of care. Thus, for example, the primary care physician’s assessment and the screening results in the primary care setting were deliberately used for the establishment of the diagnosis of depression and for the checking of inclusion and exclusion criteria, because these procedures ought to be implementable under routine conditions as well (24). The target criteria were also chosen with a view toward high clinical relevance. Remission was chosen as a primary endpoint because it is a central objective of the treatment of depression. The consistency of the findings across the various symptom-relevant target criteria, including quality of life, speak for the robustness of the findings within the study. Moreover, the effect of the intervention cannot be solely due to changes in the frequency of use of psychoactive drugs, as no statistically significant difference was found in this regard.

The limitations of the study include the large percentage of the initially contacted physicians that declined to participate in the study and the low number of subjects recruited among the patients of the participating physicians. It had been expected at the outset that primary care physicians would be more willing to participate, and that a larger number of patients would be recruited per physician’s practice, than later turned out to be the case. In fact, however, both of these rates are in the usual range for studies conducted in realistic primary care settings (25). The large number of participating practices and the low number of patients recruited per practice had a positive effect on the statistical power of the study; as a result, the goal for statistical power that had been initially set during the planning of the study was achieved in the end, despite the relatively small study sample (ebox). Moreover, the number of potential subjects that were identified serves as no more than a rough estimate of the actual recruitment potential, because, for some patients, the documentation of a depressive disorder in the medical record referred to findings of an older date, and was thus of limited informative value as to the current presence or absence of depressive manifestations. Nor was it required or stated that the patients who were identified as potential study subjects actually visited their primary care physician’s practice during the recruitment period. A further limitation arose from the cluster-randomized study design. The number of physicians who did not participate in the identification or inclusion of patients was somewhat higher in the control group than in the intervention group. It seems likely that assignment to the control group (in which no additional intervention was to be provided to the patients) lessened the physicians’ motivation to include patients in the study. Moreover, it is clear that sample bias is more likely to arise in cluster-randomized trials than when randomization is carried out at the level of individual patients; for the purposes of this study, however, the nature of the intervention made it impossible to randomize at the patient level, or to blind the patients to the intervention. Lastly, significant effects were found only for depressive manifestations and for quality of life. Precisely these two endpoints, however, are clearly of the highest relevance for the evaluation of interventions against depression.

eBOX. Design effect.

During study planning, a sample size of 85 subjects per treatment group (170 total) was calculated for the primary analysis (cf. study protocol [18]). Because a cluster-randomized study design was chosen, the included subjects were not fully independent of each other, and account had to be taken of this fact in calculating samples. On the assumption of an intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) of 10% and five patients per participating doctor’s practice, calculations in the planning stage of the study yielded a design effect of 1.46. The figures actually obtained by the completion of the study were an ICC of 9.2% and 3.5 patients per practice, yielding a finally calculated design effect of 1.23. As a result, the number of patients that needed to be recruited under the assumptions made for power analysis turned out to be reduced from 250 (170 × 1.46) to 210 (170 × 1.23). Because of this, the initially demanded statistical power of 80% was, in fact, attained despite the lower number of patients included in the study.

As for the size of therapeutic effect, the observed doubling of the rate of remission of depressive manifestations is clearly a clinically relevant result, yet even in the intervention group only about one-quarter of patients achieved a remission. A higher remission rate would have been desirable. It also seems surprising at first sight that the response rate and the remission rate were of comparable size. This is mainly due to the fact that, at baseline (timepoint T0), the patients in both groups had mean scores of approximately 10 points. Starting from this baseline, a reduction by five points is the criterion both for a remission and for a treatment response.

The findings of the GermanIMPACT study are similar to those of the original IMPACT study and its other international replications. In the study of Unnützer et al. (16), 8% of the patients in the control group and one-quarter of the patients in the intervention group were in remission at 12 months (16). The English replication of the study yielded an adjusted mean-value difference of 1.36 PHQ-9 points, which is also in agreement with our findings (26). The Dutch replication yielded remission rates of 6.3% under standard treatment and 20.7% in the intervention group; both of these figures are lower than in our study (27).

Aside from the observed effect of the intervention, its implementability in the German healthcare system is a matter of importance. To assess this, accompanying qualitative studies were carried out among the patients, primary care physicians, care managers, and supervisors. The participating primary care physicians gave the intervention an overall positive rating. The involvement of care managers was described by most of them as a helpful supportive measure that lightens the burden on the physician (28).

In conclusion, this German study, like the other IMPACT studies, revealed a significant benefit of the collaborative care model compared to usual treatment in primary care. This model can thus be regarded as solidly supported by evidence from research. From the perspective of the participating physicians, the collaborative care model represents a major enhancement of care that can markedly lighten the burden on the primary care physician. Complementary investigations from the points of view of the patients, care managers, and supervisors serve to round out the picture (29, 30). The results available to date all imply that the collaborative care model is beneficial. A health-economic assessment that is currently in progress will show whether it is cost-effective in Germany.

Supplementary Material

eMETHODS

Method

The GermanIMPACT study was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, BMBF) (FKZ: 01GY1142). Before recruitment began, it was registered with the German Registry of Clinical Studies (Deutsches Register für Klinische Studien, DRKS) under the number DRKS00003589 and extensively described in a published study protocol (18). Consultation was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg (150/12).

Design

The goal of the study was to compare GermanIMPACT treatment with treatment as usual (TAU) in primary care. Because the intervention consisted of treatment by a collaborative treatment team, a cluster-randomized, controlled study design with the doctor’s practice as the reference point for randomization was chosen, in order to avoid potential contamination effects. After their inclusion in the study, the participating practices were randomly allotted to the intervention group or the control group (IG, CG). The allotment was carried out by a computerized algorithm to obtain a 1:1 ratio, employing randomly varying block sizes (2– 6), stratified by the study locations (Freiburg/Hamburg). Despite the cluster-randomized design, the focus of the study, the intervention, and the acquisition of data were all centered on the individual patient.

Intervention

Stepwise treatment was given in the framework of the study (figure 1). It was oriented to the current condition of each patient. Treatment was provided in a collaborative effort by the primary care physician (a board-certified general practitioner or internist in primary care practice), the care manager, and the supervisor (either a physician with board certification in psychiatry and psychotherapy, or else a psychological psychotherapist).

The primary care physician diagnosed depression and initiated its treatment. He or she was in regular contact with the care manager to share information about the patient’s course and any necessary changes in the treatment.

A specially trained care manager (of whom there were five overall in the two centers) with years of experience in a health profession supported the treatment by staying in contact with the patient proactively and uninterruptedly. Support was given at intervals ranging from a week to a month, depending on the patient’s needs, and consisted of psychoeducation (about the symptoms and course of the disease, drugs, side effects, etc.), configuring the patient’s activities, relapse prophylaxis, and, where indicated, training in problem-solving. The initial contact took place in the doctor’s practice, and the subsequent ones were conducted by telephone.

There was one supervisor in Freiburg and one in Hamburg. The supervisors maintained oversight of case management for the year of the intervention and assisted the care managers with difficult situations. The primary care physicians also had the opportunity to turn to the supervisors for advice on drug treatment or emergencies. In exceptional cases, there was direct contact between the patient and a supervisor, e.g., in case of refractory symptoms. Collaborative care models are discussed in detail in References (e1– e3); an extensive description of the intervention in this study can be found in the study protocol (18).

Control treatment consisted of usual treatment by the primary care physician, i.e., without any involvement of a care manager. Patients in the control group had full access to all care options of the health care system and therefore displayed the usual pattern of treatment course.

There were no requirements concerning, or restrictions on, the prescription of drugs for patients in either of the arms of the study.

Recruitment of primary care practices

On the cluster level, primary care practices within a defined radius of the Freiburg and Hamburg city centers were invited to take part in the study. Only practices that provided care in the framework of the German legally mandated health insurance system were eligible for participation. Special practices that did not offer comprehensive primary care, practices treating fewer than 400 patients in the legally mandated health insurance system per quarter, practices with additional certified training in psychotherapy, and practices already participating in a different depression study were excluded from participation.

Patient inclusion and exclusion criteria

Men and women with clinically diagnosed unipolar depression were included in the study. The subjects were aged 60 or older and had moderate depressive manifestations, i.e., a PHQ-9 score of 10 to 14 points (19). Patients with severe depression (>14 points) were excluded; it was recommended that they be referred for secondary (specialized) treatment as recommended by the relevant guidelines. Prerequisites to participation in the study were, in the intervention group, the subject’s ability and willingness to stay in regular personal contact with the care manager over the telephone, and, in both groups, written consent to participation in the study with a total of three written questionnaires.

Patients were excluded if they had a known substance dependency disorder or marked cognitive impairment (e.g., dementia), or if they were already in psychotherapy at the time of their recruitment. Patients with bipolar disorder, psychotic manifestations, severe behavior abnormalities, or suicidality at the time of recruitment were excluded as well.

Endpoints

The main focus of the study was the change in depressive manifestations, as measured by the PHQ-9 (19), over the duration of the study, i.e., one year. The remission of depressive manifestations at 12 months was the principal objective of treatment, and thus the primary endpoint of the study; it was operationalized as a PHQ-9 score below 5 points (a commonly accepted cutoff value). The secondary endpoints were: treatment response, defined as a reduction of manifestations by at least 50%; dimensional change in manifestations; health-related quality of life, as measured by the EQ-5D-3L index score (20); manifestations of anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale [GAD-7] [21]); depression-related behavior (modified from Ludman et al. [22]), problem-solving skills (modified from Bleich and Watzke, unpublished); and resilience (Resilience Scale, short form [RS-13] [23]). Data were acquired by postal questionnaire at baseline (t0), at 6 months (t1), and at the end of the intervention, i.e., at 12 months (t2).

Sample size

On the basis of the observed effects of the IMPACT model in comparable previous studies, the sample size was planned to have an 80% chance of detecting an effect of comparable size with a two-tailed test at the conventional p<0.05 significance level. It was determined that the primary analysis would need a sample comprising 85 patients per treatment group, or 170 overall (cf. study protocol [18]). Because of design effects and the expected drop-out rate, the required overall sample size rose to 300 patients (150 per arm). On the assumption that 60 primary care practices would be recruited (30 per arm), this corresponds to 5 patients per physician. The primary analysis was conducted by the intention-to-treat principle, i.e., all patients who underwent randomization were included in the analysis according to the treatment to which they had initially been allotted. Additional sensitivity analyses were carried out by the per-protocol principle, i.e., patients were only included in the analysis if they actually received the treatment to which they had initially been allotted.

Blinding

Blinding of patients to their group allotment was impossible because of the nature of the intervention. The patients were informed only about the study conditions in the group to which their treating practice had been allotted by randomization. Neither group was informed about the conditions in the other group.

Statistical analyses

In the primary, intention-to treat analysis, a mixed-effects logistic regression model was used to compare the percentage of patients in remission 12 months after the start of the intervention. The severity of manifestations (PHQ-9) at baseline (timepoint t0) was entered into the model as a covariate for adjustment. In addition, the study center (Freiburg/Hamburg) and group membership (intervention/control group) were considered fixed effects, and possible differences between the patient clusters (patients of a practice) were considered random effects. The results were expressed as estimated adjusted marginal means (referred to as “adjusted means” in the manuscript for simplicity). Missing data were replaced with the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm (for a detailed description, see [18]).

A per-protocol analysis was additionally computed, in order to investigate the stability of the findings (analysis only of patients who completed the study as they had been allotted).

The analyses were performed with STATA 14.2.

Key Messages.

The care of elderly patients with depression in the framework of a collaborative care model was found to increase the rate of remission of depressive manifestations at one year from 10.9% to 25.6%.

Treatment by this model also significantly improved the patients’ quality of life.

These findings are comparable to those of studies from other countries regarding the IMPACT model or similar treatment models.

In this care model, care was delivered in collaboration by the primary care physician, the care manager, and the supervisor. The care manager stayed in regular contact with the patient, supervised the course of depressive manifestations, and carried out basic interventions such as psychoeducation, coordination of activities, relapse prophylaxis, and training in problem-solving if indicated.

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by Ethan Taub, M.D.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement The authors state that they have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Andreas S, Schulz H, Volkert J, et al. Prevalence of mental disorders in elderly people: the European MentDis_ICF65+ study. Br J Psychiatry J Ment Sci. 2017;210:125–131. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.115.180463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Park M, Unützer J. Geriatric depression in primary care. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2011;34:469–487. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2011.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Unützer J, Patrick DL, Diehr P, Simon G, Grembowski D, Katon W. Quality adjusted life years in older adults with depressive symptoms and chronic medical disorders. Int Psychogeriatr IPA. 2000;12:15–33. doi: 10.1017/s1041610200006177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blazer DG. Depression in late life: review and commentary. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58:249–265. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.3.m249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schulz R, Drayer RA, Rollman BL. Depression as a risk factor for non-suicide mortality in the elderly. Biol Psychiatry. 2002;52:205–225. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(02)01423-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sielk M, Altiner A, Janssen B, Becker N, de Pilars MP, Abholz HH. [Prevalence and diagnosis of depression in primary care. A critical comparison between PHQ-9 and GPs’ judgement] Psychiatr Prax. 2009;36:169–174. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1090150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jacobi F, Höfler M, Meister W, Wittchen HU. [Prevalence, detection and prescribing behavior in depressive syndromes A German federal family physician study] Nervenarzt. 2002;73:651–658. doi: 10.1007/s00115-002-1299-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bertelsmann Stiftung. Faktencheck Depression. www.faktencheck-gesundheit.de/de/publikationen/publikation/did/faktencheck-depression/ (last accessed on 19 September 2018) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Angermeyer MC, Matschinger H, Carta MG, Schomerus G. Changes in the perception of mental illness stigma in Germany over the last two decades. Eur Psychiatry. 2014;29:390–395. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2013.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rabe-Menssen C. Barrieren der Inanspruchnahme von ambulanter Psychotherapie bei älteren Menschen. Psychother Aktuell. 2011;4:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Glaesmer H, Gunzelmann T, Martin A, Brähler E, Rief W. Die Bedeutung psychischer Beschwerden für die medizinische Inanspruchnahme und das Krankheitsverhalten Älterer. Psychiatr Prax. 2008;35:187–193. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1067367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rattay P, Butschalowsky H, Rommel A, et al. Inanspruchnahme der ambulanten und stationären medizinischen Versorgung in Deutschland: Ergebnisse der Studie zur Gesundheit Erwachsener in Deutschland (DEGS1) Bundesgesundheitsblatt - Gesundheitsforschung - Gesundheitsschutz. 2013;56:832–844. doi: 10.1007/s00103-013-1665-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gum AM, Areán PA, Hunkeler E, et al. Depression treatment preferences in older primary care patients. Gerontologist. 2006;46:14–22. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.1.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dwight-Johnson M, Sherbourne CD, Liao D, Wells KB. Treatment preferences among depressed primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:527–534. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2000.08035.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bjerregaard F, Hüll M, Stieglitz RD, Hölzel L. Zeit für Veränderung - Was wir für die hausärztliche Versorgung älterer depressiver Menschen von den USA lernen können. Gesundheitswesen. 2018;80:34–39. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-107344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA J Am Med Assoc. 2002;288:2836–2845. doi: 10.1001/jama.288.22.2836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Coventry PA, Hudson JL, Kontopantelis E, et al. Characteristics of effective collaborative care for treatment of depression: a systematic review and meta-regression of 74 randomised controlled trials. PloS One. 2014;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0108114. e108114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wernher I, Bjerregaard F, Tinsel I, et al. Collaborative treatment of late-life depression in primary care (GermanIMPACT): study protocol of a cluster-randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2014;15 doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-15-351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606–613. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.EuroQol Group. EuroQol—a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy Amst Neth. 1990;16:199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092–1097. doi: 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ludman E, Katon W, Bush T, et al. Behavioural factors associated with symptom outcomes in a primary care-based depression prevention intervention trial. Psychol Med. 2003;33:1061–1070. doi: 10.1017/s003329170300816x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Leppert K, Koch B, Brähler E. Die Resilienzskala (RS) - Überprüfung der Langform RS-25 und einer Kurzform RS-13. Klin Diagn Eval. 2008;2:226–243. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trautmann S, Beesdo-Baum K. The treatment of depression in primary care. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114:721–728. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Güthlin C. Rekrutierung von Hausarztpraxen für Forschungsprojekte - Erfahrungen aus fünf allgemeinmedizinischen Studien Recruitment of Family Practitioners for Research - Experiences from Five Studies. Z Für Allg. 2012;88 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Richards DA, Hill JJ, Gask L, et al. Clinical effectiveness of collaborative care for depression in UK primary care (CADET): cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2013;347 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f4913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huijbregts KML, de Jong FJ, van Marwijk HWJ, et al. A target-driven collaborative care model for major depressive disorder is effective in primary care in the Netherlands. A randomized clinical trial from the depression initiative. J Affect Disord. 2013;146:328–337. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bireckoven MB, Niebling W, Tinsel I. [How do general practitioners evaluate collaborative care of elderly depressed patients? Results of a qualitative study] Z Evidenz Fortbild Qual Im Gesundheitswesen. 2016;117:45–55. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2016.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kloppe T. Erfolgsfaktoren, Herausforderungen und Hemmnisse in der kollaborativen Versorgung depressiv erkrankter älterer Menschen: Ein qualitativ kontrastierender Fallvergleich der Patientenperspektive zur Evaluation der Studie GermanIMPACT (QualIMP) https://beluga.sub.uni-hamburg.de/vufind/Record/1018457909?rank=2 (last accessed on 19. September .2018) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bjerregaard F, Zech J, Frank F, Stieglitz RD, Hölzel LP. Implementierbarkeit des GermanIMPACT Collaborative Care Programms zur Unterstützung der hausärztlichen Versorgung älterer depressiver Menschen - eine qualitative Interviewstudie. Z Evidenz Fortbild Qual Im Gesundheitswesen. 2018;134:42–48. doi: 10.1016/j.zefq.2018.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.Hölzel LP, Härter M, Hüll M. Multiprofessionelle ambulante psychosoziale Therapie älterer Patienten mit psychischen Störungen. Nervenarzt. 2017;88:1227–1233. doi: 10.1007/s00115-017-0407-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Hüll M, Hölzel LP. Fellgiebel A, Hautzinger M, editors. IMPACT: kooperative Behandlungsmodelle der Depression Altersdepression. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer. 2017:301–308. [Google Scholar]

- E3.Bjerregaard F, Hüll M, Stieglitz RD, Hölzel LP. Zeit für Veränderung - Was wir für die hausärztliche Versorgung älterer depressiver Menschen von den USA lernen können. Gesundheitswesen. 2018;80:34–39. doi: 10.1055/s-0042-107344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eMETHODS

Method

The GermanIMPACT study was supported by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung, BMBF) (FKZ: 01GY1142). Before recruitment began, it was registered with the German Registry of Clinical Studies (Deutsches Register für Klinische Studien, DRKS) under the number DRKS00003589 and extensively described in a published study protocol (18). Consultation was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Albert-Ludwigs-Universität Freiburg (150/12).

Design

The goal of the study was to compare GermanIMPACT treatment with treatment as usual (TAU) in primary care. Because the intervention consisted of treatment by a collaborative treatment team, a cluster-randomized, controlled study design with the doctor’s practice as the reference point for randomization was chosen, in order to avoid potential contamination effects. After their inclusion in the study, the participating practices were randomly allotted to the intervention group or the control group (IG, CG). The allotment was carried out by a computerized algorithm to obtain a 1:1 ratio, employing randomly varying block sizes (2– 6), stratified by the study locations (Freiburg/Hamburg). Despite the cluster-randomized design, the focus of the study, the intervention, and the acquisition of data were all centered on the individual patient.

Intervention

Stepwise treatment was given in the framework of the study (figure 1). It was oriented to the current condition of each patient. Treatment was provided in a collaborative effort by the primary care physician (a board-certified general practitioner or internist in primary care practice), the care manager, and the supervisor (either a physician with board certification in psychiatry and psychotherapy, or else a psychological psychotherapist).

The primary care physician diagnosed depression and initiated its treatment. He or she was in regular contact with the care manager to share information about the patient’s course and any necessary changes in the treatment.

A specially trained care manager (of whom there were five overall in the two centers) with years of experience in a health profession supported the treatment by staying in contact with the patient proactively and uninterruptedly. Support was given at intervals ranging from a week to a month, depending on the patient’s needs, and consisted of psychoeducation (about the symptoms and course of the disease, drugs, side effects, etc.), configuring the patient’s activities, relapse prophylaxis, and, where indicated, training in problem-solving. The initial contact took place in the doctor’s practice, and the subsequent ones were conducted by telephone.

There was one supervisor in Freiburg and one in Hamburg. The supervisors maintained oversight of case management for the year of the intervention and assisted the care managers with difficult situations. The primary care physicians also had the opportunity to turn to the supervisors for advice on drug treatment or emergencies. In exceptional cases, there was direct contact between the patient and a supervisor, e.g., in case of refractory symptoms. Collaborative care models are discussed in detail in References (e1– e3); an extensive description of the intervention in this study can be found in the study protocol (18).

Control treatment consisted of usual treatment by the primary care physician, i.e., without any involvement of a care manager. Patients in the control group had full access to all care options of the health care system and therefore displayed the usual pattern of treatment course.

There were no requirements concerning, or restrictions on, the prescription of drugs for patients in either of the arms of the study.

Recruitment of primary care practices

On the cluster level, primary care practices within a defined radius of the Freiburg and Hamburg city centers were invited to take part in the study. Only practices that provided care in the framework of the German legally mandated health insurance system were eligible for participation. Special practices that did not offer comprehensive primary care, practices treating fewer than 400 patients in the legally mandated health insurance system per quarter, practices with additional certified training in psychotherapy, and practices already participating in a different depression study were excluded from participation.

Patient inclusion and exclusion criteria

Men and women with clinically diagnosed unipolar depression were included in the study. The subjects were aged 60 or older and had moderate depressive manifestations, i.e., a PHQ-9 score of 10 to 14 points (19). Patients with severe depression (>14 points) were excluded; it was recommended that they be referred for secondary (specialized) treatment as recommended by the relevant guidelines. Prerequisites to participation in the study were, in the intervention group, the subject’s ability and willingness to stay in regular personal contact with the care manager over the telephone, and, in both groups, written consent to participation in the study with a total of three written questionnaires.

Patients were excluded if they had a known substance dependency disorder or marked cognitive impairment (e.g., dementia), or if they were already in psychotherapy at the time of their recruitment. Patients with bipolar disorder, psychotic manifestations, severe behavior abnormalities, or suicidality at the time of recruitment were excluded as well.

Endpoints

The main focus of the study was the change in depressive manifestations, as measured by the PHQ-9 (19), over the duration of the study, i.e., one year. The remission of depressive manifestations at 12 months was the principal objective of treatment, and thus the primary endpoint of the study; it was operationalized as a PHQ-9 score below 5 points (a commonly accepted cutoff value). The secondary endpoints were: treatment response, defined as a reduction of manifestations by at least 50%; dimensional change in manifestations; health-related quality of life, as measured by the EQ-5D-3L index score (20); manifestations of anxiety (Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale [GAD-7] [21]); depression-related behavior (modified from Ludman et al. [22]), problem-solving skills (modified from Bleich and Watzke, unpublished); and resilience (Resilience Scale, short form [RS-13] [23]). Data were acquired by postal questionnaire at baseline (t0), at 6 months (t1), and at the end of the intervention, i.e., at 12 months (t2).

Sample size

On the basis of the observed effects of the IMPACT model in comparable previous studies, the sample size was planned to have an 80% chance of detecting an effect of comparable size with a two-tailed test at the conventional p<0.05 significance level. It was determined that the primary analysis would need a sample comprising 85 patients per treatment group, or 170 overall (cf. study protocol [18]). Because of design effects and the expected drop-out rate, the required overall sample size rose to 300 patients (150 per arm). On the assumption that 60 primary care practices would be recruited (30 per arm), this corresponds to 5 patients per physician. The primary analysis was conducted by the intention-to-treat principle, i.e., all patients who underwent randomization were included in the analysis according to the treatment to which they had initially been allotted. Additional sensitivity analyses were carried out by the per-protocol principle, i.e., patients were only included in the analysis if they actually received the treatment to which they had initially been allotted.

Blinding

Blinding of patients to their group allotment was impossible because of the nature of the intervention. The patients were informed only about the study conditions in the group to which their treating practice had been allotted by randomization. Neither group was informed about the conditions in the other group.

Statistical analyses

In the primary, intention-to treat analysis, a mixed-effects logistic regression model was used to compare the percentage of patients in remission 12 months after the start of the intervention. The severity of manifestations (PHQ-9) at baseline (timepoint t0) was entered into the model as a covariate for adjustment. In addition, the study center (Freiburg/Hamburg) and group membership (intervention/control group) were considered fixed effects, and possible differences between the patient clusters (patients of a practice) were considered random effects. The results were expressed as estimated adjusted marginal means (referred to as “adjusted means” in the manuscript for simplicity). Missing data were replaced with the expectation maximization (EM) algorithm (for a detailed description, see [18]).

A per-protocol analysis was additionally computed, in order to investigate the stability of the findings (analysis only of patients who completed the study as they had been allotted).

The analyses were performed with STATA 14.2.