Abstract

Objectives

Healthcare budgets are limited, and therefore, research funds should be wisely allocated to ensure high-quality, useful and cost-effective research. We aimed to critically review the criteria considered by major Australian organisations in prioritising and selecting health research projects for funding.

Methods

We reviewed all grant schemes listed on the Australian Competitive Grants Register that were health-related, active in 2017 and with publicly available selection criteria on the funders’ websites. Data extracted included scheme name, funding organisation, selection criteria and the relative weight assigned to each criterion. Selection criteria were grouped into five representative domains: relevance, appropriateness, significance, feasibility (including team quality) and cost-effectiveness (ie, value for money).

Results

Thirty-six schemes were included from 158 identified. One-half of the schemes were under the National Health and Medical Research Council. The most commonly used criteria were research team quality and capability (94%), research plan clarity (94%), scientific quality (92%) and research impact (92%). Criteria considered less commonly were existing knowledge (22%), fostering collaboration (22%), research environment (19%), value for money (14%), disease burden (8%) and ethical/moral considerations (3%). In terms of representative domains, relevance was considered in 72% of the schemes, appropriateness in 92%, significance in 94%, feasibility in 100% and cost-effectiveness in 17%. The relative weights for the selection criteria varied across schemes with 5%–30% for relevance, 20%–60% for each appropriateness and significance, 20%–75% for feasibility and 15%–33% for cost-effectiveness.

Conclusions

In selecting research projects for funding, Australian research organisations focus largely on research appropriateness, significance and feasibility; however, value for money is most often overlooked. Research funding decisions should include an assessment of value for money in order to maximise return on research investment.

Keywords: research prioritisation, selection criteria, value for money

Strengths and limitations of this study.

The first critical review of research project selection criteria from a funder perspective in Australia.

A comprehensive review of available funding schemes, selection criteria and scoring weights to prioritise research proposals.

The recommendations provided will help research organisations streamline funding to worthy projects to maximise return on research investment.

The review takes an Australian perspective, but the findings and recommendations maybe applicable to other jurisdictions.

Introduction

Research is vital to generate evidence to guide medical decision making and improve health. Therefore, the Australian Government and various research organisations allocate considerable resources to fund clinical trials and other health research. The total expenditure on health research in Australia was around $A5.4 billion in 2014.1 Recently, the Australian Government has announced the establishment of the $A20 billion Medical Research Future Fund, which aims to improve health, contribute to a sustainable health system and provide significant economic benefits.2 There has been an emerging interest in Australia and internationally to maximise value and reduce waste in healthcare research.3–5 Although research value should be ensured throughout the continuum (ie, from research question development to implementation of the findings), directing research funds to the right research projects in the first place is key to optimise health and economic benefits from healthcare research. This is typically achieved at two levels: 1) selecting strategic research areas or topics (eg, indigenous health or cancer) to guide overall research activity and commissioning and 2) selecting specific research projects for funding from proposals put forward by researchers.6 7

Most research projects in Australia are investigator-initiated and researchers must seek financial support for their proposals through research funding organisations (eg, the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC)). However, the overall funds available for research are limited compared with the number of submissions and decisions have to be made about the best way to distribute research funds. Thus, funding organisations need to have a transparent and systematic way to evaluate and prioritise research projects for funding.5 8 9 This is often done based on the assessments of the merits of the submitted proposals according to the judgements of experts sitting on funding panels.8 10 In this process, submitted proposals are assessed and scored against predefined criteria with each criterion, or group of criteria, being assigned a weight reflecting its relative importance. Such practice corroborates with the recommendations of many international initiatives for setting research priorities where the use of explicit and comprehensive criteria is encouraged to ensure that important considerations are not overlooked during the selection process.9 11–14 In general, these criteria may include burden of the disease, equity, scientific rigour, research team capabilities, innovation and impact of research results. The choice of criteria and the scoring system may differ, depending on the needs of stakeholders involved in this exercise.9 11–14 Literature examples on prioritising research topics using explicit criteria are abundant9 11–14; however, there is a dearth of articles that provide a clear critical insight on the criteria used to select research projects from research proposals competing for funding.15

While health research funding decisions in Australia rely heavily on the ability of research proposals to meet selection criteria, it is unknown what criteria are more commonly used by research funders, how these criteria and their weights vary across funding organisations, and whether these criteria are comprehensive enough to capture all important considerations to ensure high quality and value for money research. This knowledge is important to assess the current approach of selecting and funding research projects, and to guide future efforts to optimise health research funding mechanisms in the country. Therefore, the aim of this paper was to critically review the criteria considered by major Australian research organisations in their selection of health research projects for funding.

Methods

Patient and public involvement

Patients and public were not involved.

We reviewed all research funding schemes listed on the Australian Competitive Grants Register (ACGR), which provides a comprehensive list of funding schemes that have been approved by the Australian Government as being competitive research grants.16 The identified schemes were included if they were health related, active in 2017 and had clear selection criteria which were publicly available on the funders’ websites. Health research refers to research with human health or medical purpose, including research on the aetiology, diagnosis or management of disease, mental condition or behaviour in human. To focus on schemes for funding research projects and programmes, research schemes dedicated solely to training, capacity building, equipment or infrastructure were excluded. These include fellowships, awards and scholarships as well as research and training centres.

Data extracted included scheme name, year first implemented, funding organisation, selection criteria and the relative weight assigned to each criterion. Selection criteria were grouped into five representative domains: relevance (ie, why should we do it? including the burden of disease and level of existing knowledge), appropriateness (ie, should we do it? including scientific rigour and suitability to answer the research question), significance of research outcomes (ie, what will we get out of it? including impact and innovation), feasibility (ie, can we do it? including team quality and research environment) and cost-effectiveness (ie, is the proposed research potentially good value for money?).9 12 The domains were selected based on the lists of criteria and categories suggested in comprehensive tools for research prioritisation including the Essential National Health Research Approach (relevance, appropriateness, feasibility and significance),12 Child Health and Nutrition Research Initiative (answerability, effectiveness, deliverability and impact)11 and the Checklist for Health Research Priority Setting (benefits, feasibility and cost-effectiveness).9 Disagreements related to assigning criteria to their representative domains were either resolved by discussion or the involvement of a third reviewer who was provided with the full assessment or selection criteria for consensus decision-making. A domain was counted under a given scheme if at least one criterion within that domain is reported in the selection criteria of that scheme. Table 1 provides a description of the representative domains.

Table 1.

Description of domains and relevant criteria9 12

| Domain | Definition |

| Relevance | The key question for this domain is “why should we do it?” The proposed research is pertinent to the health problems of interest. It takes into consideration burden of disease, equity, alignment with national/organisational objectives and the level of existing knowledge in relation to the intervention. |

| Appropriateness | The key question for this domain is “should we do it?” The proposed research is well suited to answer the decision problem (ie, answerability). It takes into consideration ethical, moral and legal acceptability, and scientific rigour. |

| Significance | The key question for this domain is “what will we get out of it?” It represents the benefit of implementing/translating the research results. It takes into consideration the impact on health, innovation and ability to foster capacity building and collaboration. |

| Feasibility | The key question for this domain is “can we do it?” The focus is on the chances of research success. It considers team quality (track record) and capability, research environment and the research plan. |

| Cost-effectiveness | The key question for this domain is ‘is the research cost-effective?’ This theme focuses on the value for money of the research proposal and budget justification. It considers the costs and expected benefits of conducting research. |

Results

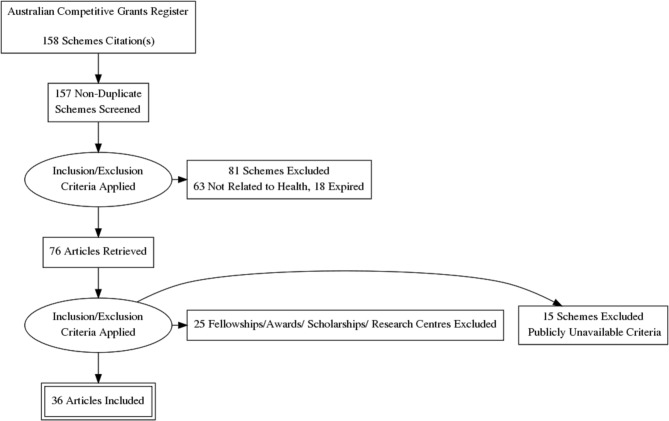

Thirty-six schemes met our inclusion criteria from 158 schemes listed on the 2017 ACGR. Figure 1 summarises the review process.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the review.

One-half of the schemes were under the NHMRC. Five schemes (14%) were specifically for research in cancer, four (11%) for dementia, four (11%) for mental health and three (8%) for diabetes. A summary of the selection criteria considered by each scheme is presented in table 2. Further details on the selection criteria and scoring weights are provided in online supplementary file.

Table 2.

Selection criteria domains for schemes and funding organisations

| Organisation and scheme name | Relevance | Appropriateness | Significance | Feasibility | Cost-effectiveness | |||||||||||

| Burden | National/ Organisational priorities |

Existing knowledge |

Scientific quality |

Answerability | Ethical/ Moral |

Innovation | Impact | Translation/ Implementation |

Capacity/ Collaboration |

Research team quality |

Environment | Stakeholders involved |

Research plan |

Budget justification |

Value for money |

|

| NHMRC | ||||||||||||||||

| Boosting Dementia Research Grants32 | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Dementia Research Team Grants33 | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - |

| Development Grants34 | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - |

| Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases—Chronic Lung Disease35 | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - |

| Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases—Mental Disorders35 | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - |

| Global Alliance for Chronic Diseases—Type 2 Diabetes Countries35 | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - |

| National Institute for Dementia Research Grants36 | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| NHMRC/NSFC—Prediction and Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes37 | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - |

| Northern Australia Tropical Disease Collaborative Research Programme38 | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - |

| Partnership Projects39 | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - | |

| Programme Grants40 | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - |

| Project Grants41 | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - |

| Targeted Call—Engaging Young Adults to Improve Eating Behaviours and Health Outcomes42 | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - |

| Targeted Call—Mental Health: Suicide Prevention in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Youth43 | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - |

| Targeted Call—Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples44 | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - |

| Targeted Call—Preparing Australia for the Genomics Revolution45 | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - |

| Targeted Call—Wind Farms and Human Health46 | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - |

| Translational Research Projects for Improved Healthcare47 | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | ✔ |

| Cancer Australia | ||||||||||||||||

| Priority-driven Collaborative Cancer Scheme48 | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | - |

| Support for Cancer Clinical Trials Programme—Existing National Cooperative Oncology Groups49 | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| National Breast Cancer Foundation | ||||||||||||||||

| Accelerator Research Grant50 | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - |

| Innovator Grant51 | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - |

| Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade | ||||||||||||||||

| Tropical Disease Research Regional Collaboration Initiative52 | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| Alzheimer’s Australia Dementia Research Foundation | ||||||||||||||||

| Dementia Grants Programme53 | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - |

| Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists | ||||||||||||||||

| ANZCA Research Grants Programme54 | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - |

| Australian Rotary Health | ||||||||||||||||

| Mental Health Research Grants55 | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - |

| Bupa Foundation | ||||||||||||||||

| Bupa Health Foundation56 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - |

| Cure for MND Foundation | ||||||||||||||||

| Translational Research Grants57 | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - |

| Diabetes Australia Research Trust | ||||||||||||||||

| General Grants58 | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - |

| Healthway (Western Australian Health Promotion Foundation) | ||||||||||||||||

| Health Promotion Intervention Research Grants59 | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ |

| HCF Research Foundation | ||||||||||||||||

| Health Services Research Grants60 | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - |

| Motor Neurone Disease Research Institute of Australia | ||||||||||||||||

| Motor Neurone Disease Research Grants61 | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | - | - | - |

| Multiple Sclerosis Research Australia | ||||||||||||||||

| Research Grants62 | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | - | - |

| National Heart Foundation of Australia | ||||||||||||||||

| Vanguard Grants63 | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - |

| Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia | ||||||||||||||||

| New Concept Grant64 | - | - | - | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | - |

| The Movember Group and beyondblue | ||||||||||||||||

| Australian Mental Health Initiative65 | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | ✔ | - | ✔ | - | ✔ | ✔ | - | - |

ANZCA, Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists; HCF, The Hospitals Contribution Fund of Australia; MND, motor neuron disease; NHMRC, National Health and Medical Research Council; NSFC, National Natural Science Foundation of China.

bmjopen-2018-026207supp001.pdf (154.8KB, pdf)

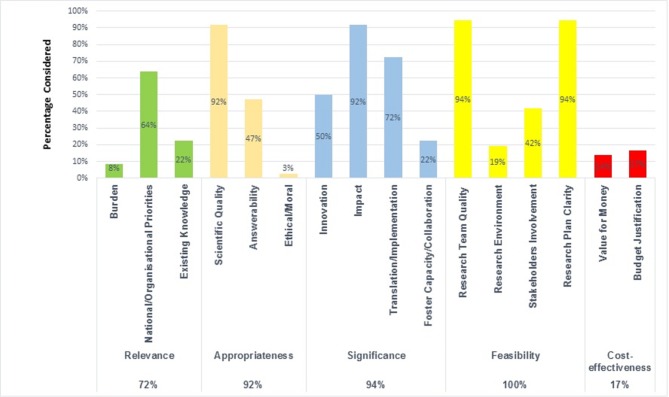

The most commonly used criteria were research team quality and capability (94%), research plan clarity (94%), scientific quality of the proposal (92%) and research impact (92%). Criteria considered less commonly were existing knowledge (22%), fostering collaboration (22%), research environment (19%), budget justification (17%), value for money (14%), disease burden (8%) and ethical/moral considerations (3%). When selection criteria were grouped into relevant domains, all schemes considered feasibility criteria, 94% of the schemes considered significance, 92% considered appropriateness, 72% considered relevance and only 17% considered cost-effectiveness. Only five schemes (14%) considered all five domains namely, NHMRC National Institute for Dementia Research Grants, NHMRC Boosting Dementia Research Grants, Cancer Australia Clinical Trials Programme, the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade Tropical Disease Research, Health Promotion Intervention Research Grants. Figure 2 depicts the distribution of selection criteria.

Figure 2.

Overall research criteria and their representative domains.

When reported, the relative weights for the selection criteria also varied across schemes with 20%–75% for feasibility, 20%–60% for each appropriateness and significance, 15%–33% for value for money and 5%–30% for relevance criteria.

Discussion

Using a predefined set of selection criteria is a transparent approach to select and prioritise high-quality research projects for funding. Typically, the relevance of research proposals is gauged with criteria that are mostly related to the project’s ability to advance knowledge7; however, these criteria should also reflect the mandate of the funding organisation and the purpose of the funding scheme.9 12 A broad range of criteria were reported in the included schemes with a clear focus on the quality of the research team, research plan, scientific rigour, impact and translation/implementation potential. The identified schemes, within the same organisation and across organisations, had variable selection criteria and scoring weights. When grouped into representative domains, funding organisations in Australia appear to focus on research relevance, appropriateness, significance and feasibility; however, cost-effectiveness of research projects was largely overlooked. The observed variation in criteria and scoring weights in our review may be justified by the different emphasis placed on certain aspects to achieve the outcomes sought under each scheme. For instance, collaborative and partnership schemes focused on partnership strengths, collaborative gains and team integration.

The only aspect that was considered by all schemes was research feasibility with a clear emphasis on the quality of the research team. Team quality and capability (often based on past performance) is vital to ensure that the funded research projects can be effectively conducted within the time and budget specified; nevertheless, over relying on this criterion may result in giving disproportionate share of funding to established teams at the expense of more novel and innovative projects. This bias can be reduced by introducing initiatives that fund innovative research ideas with high impact potential such as the ‘Grand Challenges’ initiative and the NMRC ‘Ideas Grants’.5 6 Notably, there are important criteria that were not considered by most of the included schemes. Equity considerations were not explicitly mentioned as a selection criterion, and ethical/moral considerations were only considered in one scheme. This might be explained by the implicit assumptions that all submitted proposals will be approved by ethics committees and that equity is addressed by targeted research grants (eg, Research in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders) or considered during final deliberations to select proposals for funding. However, without clarity about where the responsibility for ethical and equity considerations lies there is the potential for these criteria to be overlooked.

There has been a shift away from exclusive technical merit-review of proposals towards relevance of research funding as judged by multiple stakeholders.7 17 18 Research organisations, particularly if publicly funded, are increasingly expected to make the best use of taxpayers’ money to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set.19 20 For example, Chalmers et al recommended to engage potential users of research in research prioritisation, justify additional research by systematic reviews to show what is already known and to periodically monitor and analyse impact of funded research.4 5 21 Around 40% of the schemes in our study considered stakeholders’ involvement (ie, consumers and/or clinicians); however, the level of stakeholders’ engagement and influence on funding decisions was unclear. Considering the needs and inputs of various stakeholders such as patients, caregivers, clinicians and decision makers is essential to fund research that is useful to solve real-life problems. The experience of the Patient-Centred Outcomes Research Institute in the USA suggested that involving patients and stakeholders alongside scientists in reviewing research applications is influential in panel discussions and merit review outcomes.18 22 Despite its importance to avoid research duplication, only 22% of the identified schemes considered existing knowledge, but none of the schemes explicitly required a systematic review of literature to demonstrate knowledge gaps. Although conducting systematic reviews to identify knowledge gaps may not be required when responding to targeted research calls or when research is commissioned, since evidence review is often conducted by the commissioning organisations, showing what is already known should be required by researchers submitting investigator-initiated proposals. Our results echo the findings of a review of the extent to which 11 international organisations.3 In that review, only one organisation required reference to relevant systematic reviews in all funding applications and four funders required systematic reviews for funding clinical trials.3

Another important value aspect is the impact of funded research. Research impact broadly refers to generated benefits in terms of knowledge production, informing policy, capacity-building, health benefits and broader social and economic benefits.19 23 The presence of multidimensional benefits reflects how the definition of impact varies with the perspectives of different stakeholders as patients, clinicians, government, industry and academia.19 23 24 The majority of the schemes in our review considered research impact as a funding criterion with elements including advancing knowledge, improving health outcomes and scientific publications; however; the schemes did not specify how these benefits should be measured and presented in funding proposals. Greenhalgh et al have reviewed established approaches to measure impact (eg, Research Impact Framework, Canadian Academy of Health Sciences and UK Research Excellence Framework).19 They have concluded that approaches to impact assessment differed according to the circumstances and purpose of funding, they also noted that the most robust approaches are complex and labour-intensive and called for research on research impact.19 Of note, most of these approaches were designed to measure research impact retrospectively, that is, to evaluate the benefits of particular research programmes that have already been conducted; notwithstanding, funding organisations and researchers need prospective approaches to infer the benefit of new research to support research funding decisions. Incorporating impact evaluation frameworks into the priority-setting processes is a necessary requirement that should be studied.7

Importantly, funding organisations may implicitly assume that selecting high impact projects would ensure value for money; nevertheless, value for money cannot be established without explicitly comparing the costs and expected benefits of proposals competing for funding.6 25 26 This is because research budgets are finite and decisions must be made about how to allocate these funds (ie, which research proposals should be funded) to maximise benefits. Failure to consider this aspect brings the risk of funding research projects where the costs of conducting research outweigh the expected research benefits (ie, research projects that are not cost-effective). This would result in ‘opportunity cost’, which is the benefit forgone elsewhere by adopting suboptimal choices.27 Interestingly, none of the schemes that required demonstration of value for money provided guidelines on how the cost-effectiveness of research projects should be performed and presented. Of note, there are rigorous analytical methods to prospectively quantify the expected benefits of research on improving health outcomes, the key analytical approaches are the ‘prospective payback of research’ (a similar approach to return on investment) and the value of information approach.6 8 Under the payback approach, the value of a research study is typically inferred from its ability to result in a beneficial change in clinical practice.28 The value of information approach, on the other hand, considers the uncertainty in the relevant available evidence (eg, from systematic reviews and meta-analyses) and the consequences of this uncertainty (eg, implementing a suboptimal intervention).25 29 Research benefits calculated by these approaches are scaled up by considering the population expected to benefit from research results over time, and these benefits are compared with research budget to inform cost-effectiveness.26 30 It should be acknowledged; however, that assigning monetary value to research benefits and conducting economic evaluation of research proposals may not be acceptable or feasible (eg, due to capacity considerations) by some jurisdictions. Therefore, the decision making context and the availability of resources to conduct such analyses should be carefully considered before incorporating these approaches into priority-setting processes. Furthermore, it should be emphasised that the cost-effectiveness criterion should not be the only consideration when making research funding decisions. It is recommended that cost-effectiveness be used to supplement (ie, in combination with) other considerations that deemed important to the stakeholders.8 23

A limitation to our work is that we only reviewed active grant schemes listed on the ACGR; and therefore, some grant schemes may not have been included in our review; however, the ACGR is a comprehensive registry of major research grants by leading funding organisations in Australia. Additionally, it is noted that selection criteria, and schemes, change over time to meet political and administrative objectives. For example, the NHMRC is revising grant schemes as well as the selection criteria and processes for a new series of grants to commence funding in 2019.31 In addition, our review was limited by the amount of publicly available information for each scheme, and thus, we could not extract some important elements as scheme budgets and the knowledge generation and translation frameworks adopted by various funding organisations. The next step for this research would be to engage with funding organisations to gain further insights on their approaches to prioritise research proposals for funding.

In conclusion, healthcare research is vital to improve health; however, there is a need to ensure that funded research is relevant and value for money. In selecting research projects for funding, Australian research funding organisations focus on research appropriateness, significance and feasibility; nevertheless, other important criteria should not be overlooked such as equity and stakeholders’ engagement. Importantly, research funding decisions should include an assessment of value for money in order to maximise return on research investment.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Professor Joanne Aitken for her contribution to this manuscript.

Footnotes

Contributors: HWT and PAS conceptualised the manuscript. HWT and NE-S conducted the review of funding criteria and drafted the manuscript. PAS and SKC critically reviewed the findings. All authors contributed to the writing, review and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: Haitham Tuffaha is supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) fellowship (GNT1121232). This project is funded by Menzies Health Institute Queensland and the Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Further details on the selection criteria and scoring weights are provided in online supplementary file.

References

- 1. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Health expenditure Australia 2015–16. https://www.aihw.gov.au/getmedia/3a34cf2c-c715-43a8-be44-0cf53349fd9d/20592.pdf.aspx?inline=true.

- 2. The Australian Government. DoH medical research future fund. https://beta.health.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/medical-research-future-fund/about-the-mrff.

- 3. Nasser M, Clarke M, Chalmers I, et al. What are funders doing to minimise waste in research? Lancet 2017;389:1006–7. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30657-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Moher D, Glasziou P, Chalmers I, et al. Increasing value and reducing waste in biomedical research: who’s listening? Lancet 2016;387:1573–86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00307-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, et al. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. The Lancet 2014;383:156–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62229-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Andronis L. Analytic approaches for research priority-setting: issues, challenges and the way forward. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res 2015;15:745–54. 10.1586/14737167.2015.1087317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cartier Y, Creatore MI, Hoffman SJ, et al. Priority-setting in public health research funding organisations: an exploratory qualitative study among five high-profile funders. Health Res Policy Syst 2018;16:53 10.1186/s12961-018-0335-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Tuffaha HW, Andronis L, Scuffham PA. Setting Medical Research Future Fund priorities: assessing the value of research. Med J Aust 2017;206:63–5. 10.5694/mja16.00672 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Viergever RF, Olifson S, Ghaffar A, et al. A checklist for health research priority setting: nine common themes of good practice. Health Res Policy Syst 2010;8:36 10.1186/1478-4505-8-36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Health and Medical Research Council. NHmrc principles of peer review. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/grants-funding/peer-review/nhmrc-principles-peer-review.

- 11. Rudan I, Gibson J, Kapiriri L, et al. Setting priorities in global child health research investments: assessment of principles and practice. Croat Med J 2007;48:595–604. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Okello DCP. The COhred working group on priority setting a manual for research priority setting using the enhr strategy. http://www.cohred.org/downloads/578.pdf.

- 13. Ghaffar ACT, Matlin SA, Olifson S. The 3D combined approach matrix: An improved tool for setting priorities in research for health. http://www.webcitation.org/query.php?url=http://www.globalforumhealth.org/content/download/7860/50203/file/CAM_3D_GB.pdf.

- 14. WHO. Ad hoc committee on health research relating to future intervention options. Investing in health research and development 1996. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/63139/1/TDR_GEN_96.2.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nasser M, Welch V, Ueffing E, et al. Evidence in agenda setting: new directions for the cochrane collaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 2013;66:469–71. 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2012.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Australian competitive grants register. https://www.education.gov.au/australian-competitive-grants-register.

- 17. McLean RKD, Sen K. Making a difference in the real world? A meta-analysis of the quality of use-oriented research using the Research Quality Plus approach. Res Eval 2018;64:rvy026–rvy. 10.1093/reseval/rvy026 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Forsythe LP, Frank LB, Tafari AT, et al. Unique review criteria and patient and stakeholder reviewers: analysis of pcori’s approach to research funding. Value Health 2018;21:1152–60. 10.1016/j.jval.2018.03.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Greenhalgh T, Raftery J, Hanney S, et al. Research impact: a narrative review. BMC Med 2016;14:78 10.1186/s12916-016-0620-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chalmers I, Bracken MB, Djulbegovic B, et al. How to increase value and reduce waste when research priorities are set. Lancet 2014;383:156–65. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62229-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chalmers I, Glasziou P. Systematic reviews and research waste. Lancet 2016;387:122–3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01353-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fleurence RL, Forsythe LP, Lauer M, et al. Engaging patients and stakeholders in research proposal review: the patient-centered outcomes research institute. Ann Intern Med 2014;161:122–30. 10.7326/M13-2412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Donovan C. State of the art in assessing research impact: introduction to a special issue. Res Eval 2011;20:175–9. 10.3152/095820211X13118583635918 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Donovan C. The Australian Research Quality Framework: A live experiment in capturing the social, economic, environmental, and cultural returns of publicly funded research. New Dir Eval 2008;2008:47–60. 10.1002/ev.260 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Claxton K, Posnett J. An economic approach to clinical trial design and research priority-setting. Health Econ 1996;5:513–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Tuffaha HW, Gordon LG, Scuffham PA. Value of information analysis informing adoption and research decisions in a portfolio of health care interventions. MDM Policy Pract 2016;1:238146831664223 10.1177/2381468316642238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Drummond M, Sculpher M, Torrance G, et al. ; Methods for the economic evaluation of health care programmes. Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Townsend J, Buxton M, Harper G. Prioritisation of health technology assessment. The PATHS model: methods and case studies. Health Technol Assess 2003;7:iii, 1–82. 10.3310/hta7200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Claxton K, Griffin S, Koffijberg H, et al. How to estimate the health benefits of additional research and changing clinical practice. BMJ 2015;351:h5987 10.1136/bmj.h5987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bennette CS, Veenstra DL, Basu A, et al. Development and evaluation of an approach to using value of information analyses for real-time prioritization decisions within swog, a large cancer clinical trials cooperative group. Med Decis Making 2016;36:641–51. 10.1177/0272989X16636847 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. National Health and Medical Research Council. Peer review consultation paper. https://consultations.nhmrc.gov.au/public_consultations/nhmrc-grant-program-review.

- 32. National Health and Medical Research Council-Boosting Dementia Research Grants. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/book/nhmrc-funding-rules-2017/nhmrc-funding-rules-2017/boosting-dementia-research-grants-scheme/3.

- 33. National Health and Medical Research Council-Dementia Research Team Grants. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/book/nhmrc-funding-rules/section-o-dementia-research-team-grants/o6-assessment.

- 34. National Health and Medical Research Council-Development Grants. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/book/nhmrc-funding-rules-2017/development-grants-scheme-specific-funding-rules-funding-commencing/4.

- 35. National Health and Medical Research Council-Global Alliance for ChronicDiseases(GACD). https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/book/nhmrc-funding-rules-2017/global-alliance-chronic-diseases-gacd-scheme-specific-funding-rules/4.

- 36. National Health and Medical Research Council-NHMRC National Institute for Dementia Research Grants. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/book/5-assessment-criteria-0.

- 37. National Health and Medical Research Council-NHMRC/NSFC Joint Call for Research to Enhance Prediction and Improve the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes in China and Australia. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/book/3-assessment-criteria-1.

- 38. National Health and Medical Research Council-Northern Australia Tropical Disease Collaborative Research Programme-specifi. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/book/nhmrc-funding-rules-2016/NHMRC-funding-rules-2016/0rthern-australia-tropical-disease/3.

- 39. National Health and Medical Research Council-Partnership Projects. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/book/nhmrc-funding-rules-2017/nhmrc-funding-rules-2017/partnership-projects-scheme-specific-3.

- 40. National Health and Medical Research Council-Program Grants. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/book/nhmrc-funding-rules-2017/program-grants-scheme-specific-funding-rules-funding-commencing-2019/4.

- 41. National Health and Medical Research Council-Project Grants. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/book/nhmrc-funding-rules-2017/project-grants-scheme-specific-funding-rules-funding-commencing-2018/4.

- 42. National Health and Medical Research Council-Targeted Call for Research into Engaging and Retaining Young Adults. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/book/8-assessment-applications-1.

- 43. National Health and Medical Research Council-Targeted Call for Research into MENTAL HEALTH: Suicide Prevention in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Youth.

- 44. National Health and Medical Research Council-"Targeted Call for Research into Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorder among Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/grants-funding/apply-funding/targeted-and-urgent-calls-research/fetal-alcohol-spectrum-disorder-ta-0.

- 45. National Health and Medical Research Council-Targeted Call for Research into Preparing Australia for the Genomics Revolution in Health Care (Genomics TCR). https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/book/8-assessment-applications.

- 46. National Health and Medical Research Council-Targeted Call for Research into Wind Farms and Human Health. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/book/8-assessment-applications-0.

- 47. National Health and Medical Research Council-Translational Research Projects for Improved Health Care. https://www.nhmrc.gov.au/_files_nhmrc/file/research/translational_research_projects_v11.pdf.

- 48. Cancer Australia-Priority-Driven Collaborative Cancer Scheme. https://canceraustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/2017_round_pdccrs_grant_guidelines_rules_for_applicants_standard_project_grants_161221_2.pdf.

- 49. Cancer Australia-Support for Cancer Clinical Trials Program-Existing National Cooperative Oncology Groups. https://canceraustralia.gov.au/sites/default/files/publications/grant_guidelines.pdf.

- 50. National Breast Cancer Foundation-Accelerator Research Grant. http://docplayer.net/50962154-National-breast-cancer-foundation-accelerator-research-grant-application-guidelines.html.

- 51. National Breast Cancer Foundation-Innovator Grant. http://nbcf.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/NBCF_2017_In0vator_Grant_Guidelines.pdf.

- 52. Tropical Disease Research Regional Collaboration Initiative. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade-Tropical Disease Research Regional Collaboration Initiative.

- 53. Alzheimer’s Australia Dementia Research Foundation-Dementia Grants Program https://www.dementiaresearchfoundation.org.au/sites/default/files/2017_DEMENTIA_GRANTS_PROGRAM-Information_for_Applicants.pdf.

- 54. Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists-ANZCA Research Grants Program http://www.anzca.edu.au/documents/fdn-2018-project-grant-guide-incl-simulation_educa.pdf.

- 55. Australian Rotary Health-Mental Health Research Grants. https://australianrotaryhealth.org.au/research/current-research-opportunities/.

- 56. BUPA Foundation (Australia) limited-Bupa Health Foundation http://www.bupa.com.au/about-us/bupa-health-foundation/about.

- 57. Cure for Motor Neurone disease Foundation-Translational Research Grants. https://curemnd.org.au/research/research-grants/.

- 58. Diabetes Australia Research Trust General Grants https://static.diabetesaustralia.com.au/s/fileassets/diabetes-australia/bdd46dd3-2222-4d14-ad27-42af9e97506c.pdf.

- 59. Healthway (Western Australian Health Promotion Foundation)-Health Promotion Intervention Research Grants. https://www.healthway.wa.gov.au/grants-programs/health-promotion-research-grants/apply-0w/.

- 60.HCF Research Foundation-Health Services Research Grants. https://www.hcf.com.au/about-us/hcf-foundation/hcf-foundation-applications.

- 61. Motor Neurone Disease Research Institute of Australia-Motor Neurone Disease Research Grants. http://www.mndaust.asn.au/Documents/Research-documents/Grants/2017-funding-round/Application_Guidelines_GIA_final.aspx.

- 62. Multiple Sclerosis Research Australia-Research Grants. https://msra.org.au/annual-funding-opportunities/types-of-grants/.

- 63. National Heart Foundation of Australia-Vanguard Grants. https://www.heartfoundation.org.au/images/uploads/researchers/2017_VG_Instructions_FINAL.pdf.

- 64. Prostate Cancer Foundation of Australia-New Concept Grant. http://www.prostate.org.au/media/784704/2017-PCFA-Guide-for-Applicants-New-Concept-Grant.pdf.

- 65. The Movember Group and Beyondblue- Australian Mental Health Initiative. https://au.movember.com/uploads/files/2013/Programs/Movember%20Australian%20Mental%20Health%20Initiative%20RFA%20Nov%202013.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-026207supp001.pdf (154.8KB, pdf)