Abstract

Objectives

To update the current evidence base on paediatric postdischarge mortality (PDM) in developing countries. Secondary objectives included an evaluation of risk factors, timing and location of PDM.

Design

Systematic literature review without meta-analysis.

Data sources

Searches of Medline and EMBASE were conducted from October 2012 to July 2017.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included if they were conducted in developing countries and examined paediatric PDM. 1238 articles were screened, yielding 11 eligible studies. These were added to 13 studies identified in a previous systematic review including studies prior to October 2012. In total, 24 studies were included for analysis.

Data extraction and synthesis

Two independent reviewers extracted and synthesised data using Microsoft Excel.

Results

Studies were conducted mostly within African countries (19 of 24) and looked at all admissions or specific subsets of admissions. The primary subpopulations included malnutrition, respiratory infections, diarrhoeal diseases, malaria and anaemia. The anaemia and malaria subpopulations had the lowest PDM rates (typically 1%–2%), while those with malnutrition and respiratory infections had the highest (typically 3%–20%). Although there was significant heterogeneity between study populations and follow-up periods, studies consistently found rates of PDM to be similar, or to exceed, in-hospital mortality. Furthermore, over two-thirds of deaths after discharge occurred at home. Highly significant risk factors for PDM across all infectious admissions included HIV status, young age, pneumonia, malnutrition, anthropometric variables, hypoxia, anaemia, leaving hospital against medical advice and previous hospitalisations.

Conclusions

Postdischarge mortality rates are often as high as in-hospital mortality, yet remain largely unaddressed. Most children who die following discharge do so at home, suggesting that interventions applied prior to discharge are ideal to addressing this neglected cause of mortality. The development, therefore, of evidence-based, risk-guided, interventions must be a focus to achieve the sustainable development goals.

Keywords: postdischarge mortality, pedatrics, global health, systematic review, developing countries

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Extensive literature search of Medline and Embase with independent screening of all abstracts and eligible full-text publications by two investigators.

Extensive data extraction on risk factors for mortality within each study population.

Few studies were prospective and focused on measurement of post-discharge mortality as a primary outcome.

Heterogeneity in populations, duration of follow-up and high proportion of loss to follow-up may limit the external validity and underestimate outcome rates.

No optimal method to assess the risk of bias in included studies.

Introduction

The third of 17 United Nations sustainable development goals (SDGs) emphasises preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age, with all countries aiming to reduce under-5 mortality to at least as low as 25 deaths per 1000 live births by the year 2030.1 Although significant progress was made during the Millennium Development Goal era (1990–2015), preventable childhood deaths remain high in Southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.2 These deaths result largely from infectious diseases (including malaria, pneumonia, diarrhoea, etc), which lead to sepsis.3 Children are particularly vulnerable in the months following hospital discharge, with a growing body of research demonstrating that postdischarge deaths occur in similar numbers as during hospital admission. Despite the staggering burden of postdischarge mortality, this issue has been largely neglected when examining paediatric mortality from infectious disease. The 2017 United Nations World Health Assembly (WHA) resolution calling for improvement in prevention, diagnosis and management of sepsis is timely as it emphasises the need for improved follow-up care, particularly for developing countries, within their recommended actions for reducing the burden of sepsis globally.4 Member states are urged to emphasise the impact of sepsis on public health, of which postdischarge mortality is a crucial aspect.2 Thus, as the international community works towards achieving the WHA resolution and the third SDG, addressing the burden of paediatric postdischarge mortality is of utmost importance.

A systematic literature review conducted in 2012 examined the burden of paediatric postdischarge mortality in resource-poor countries.5 This systematic review found that the rate of paediatric postdischarge death is often as high as in-hospital mortality rates, with two-thirds of these deaths occurring outside the health system, usually at home. Common risk factors for postdischarge mortality included young age, malnutrition, HIV, pneumonia and recent prior admissions.

Despite the high burden of postdischarge death, this issue continues to receive insufficient recognition at either national or international levels. The lack of research and data highlighting the burden of postdischarge mortality relegates care following discharge as a low priority to policy makers. Additional studies published since the last systematic review contribute to the growing evidence base that can galvanise both researchers and policy makers to action.

The purpose of this systematic review, therefore, is to update the literature addressing the critical nature of paediatric postdischarge mortality in resource-poor settings, propelling research and interventions towards the goal of reduced child mortality.

Methods

Objective and study eligibility criteria

The primary objective was to determine the risk factors and rates of mortality in children following discharge from hospitals in developing countries. Table 1 outlines the study inclusion eligibility, determined through the Population, Interventions, Comparisons, Outcomes and Study Design format.

Table 1.

Population, Interventions, Comparisons, Outcomes and Study Design

| Population | Paediatric patients discharged from hospitals in developing countries, as defined as those countries currently (2016) classified by the United Nations Development Programme as having a low Human Development Index plus those countries included previously (2011) as having a low Human Development Index.6 7 |

Exclusion criteria:

| |

| Interventions | Studies may or may not include an interventional arm (ie, both arms of an RCT will be included). |

| Comparisons | NA |

| Outcomes | Primary outcome:

|

| Study design | Eligible study designs include the following:

|

NA, not applicable.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the design or conduct of this study.

Search strategy

Articles published and indexed between 1 January 2012 and 18 July 2017 were identified using the MEDLINE and EMBASE databases within the OVID platform. The detailed search strategy for each database is outlined in online supplementary appendix 1. Studies conducted prior to 2012 were identified from a prior publication, using a similar search strategy.5 Articles were included if the study was conducted in a developing country (defined as countries currently (2016) classified by the United Nations Development Programme as having a low Human Development Index plus those countries included previously (2011) as having a low Human Development Index6 7), included children admitted to hospital for medical reasons, and included follow-up to capture vital status during the postdischarge period.5 6 Furthermore, references of all included articles were reviewed to identify other potentially eligible studies not captured in the systematic search.

bmjopen-2018-023445supp001.pdf (183KB, pdf)

Study selection and data extraction

Two investigators (BN, LE) independently screened articles during two rounds of review. The first round consisted of reviewing all abstracts for the presence of specific exclusion criteria. The second round of review consisted of a detailed review of remaining articles in full-text format. In both rounds, any discrepancies were resolved through discussion and consensus. A third investigator (MOW) provided arbitration for any discrepancies not resolved through consensus.

For eligible studies, the characteristics extracted included author, title and year of publication, year of study, country, study design, facility, population (diarrhoea, malaria, all admissions, etc), time of enrolment (admission or discharge), number of subjects, age, sex and study eligibility criteria. Outcomes extracted included total number of subjects who died both in-hospital and following discharge, timing and location of postdischarge deaths, follow-up method and losses to follow-up, number of postdischarge rehospitalisations and health seeking, timing of rehospitalisations and health seeking and risk factors for postdischarge mortality. When extracting data on risk factors, the results of multivariate analysis were preferentially extracted over univariate analyses.

Risk of bias

A formal risk of bias assessment, such as the Newcastle Ottawa Quality Assessment Scale for Cohort Studies, was not conducted since the primary outcome of the rate of postdischarge mortality was not exposure related among included studies. Primary factors leading to potential bias include the per cent follow-up as well as whether inclusion criteria were correctly applied to enrolled subjects, leading to a representative sample of the population. While the former was included in the outcome characteristics, the latter was not defined in any study. Thus, proportion of children successfully followed remains the primary indicator of risk of bias.

Data analysis and outcomes

Microsoft Excel (Redmond, Washington, USA) was used to compile extracted data. Due to varying populations, risk factors, definitions and types of results (eg, OR, HR), a formal meta-analysis was not deemed possible. Therefore, the analysis was descriptive in nature. The primary outcome was the proportion of discharged subjects who died during the postdischarge period. Secondary outcomes included the proportion of total deaths (in-hospital and postdischarge), which occurred following discharge, as well as risk factors associated with postdischarge mortality. Given that several distinct populations were evaluated, results were reported according to the underlying study population. Studies were grouped according to five underlying populations: (1) all admissions including those for infectious diseases, (2) malnutrition, (3) respiratory infection, (4) diarrhoeal diseases and (5) malaria/anaemia.

Results

Summary of included articles

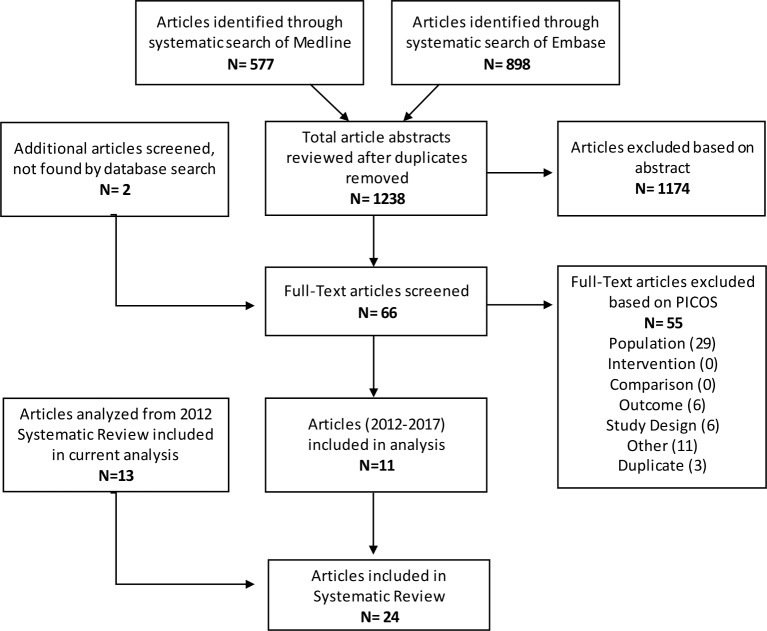

A total of 1238 articles were identified through the systematic searches, with two additional articles identified independently. Of these, 1174 were excluded at the abstract stage and a further 55 were excluded during the full-text screening stage, resulting in 11 eligible studies (figure 1, online supplementary appendix 2). These 11 studies were added to the 13 studies identified prior to 2012 through a similar systematic search,5 resulting in a total of 24 included studies (table 2). Studies were grouped according to underlying population. Three studies examined either all admissions or all infectious admissions, five examined malnutrition, seven respiratory infection, three diarrhoeal diseases and six included children with malaria and/or anaemia. Seven randomised controlled trials, 12 prospective cohorts, 2 retrospective cohorts and 3 case-control studies were included. Two studies examined those admitted to a health centre, whereas the remaining 22 were conducted at various types and levels of hospitals. All studies were performed in a single country, and Bangladesh was the only non-African country in which included studies were conducted.

Figure 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram.

Table 2.

Study characteristics

| Author ID | Years of study | Country | Design | Facility type | Population | Number of subjects | Age range | Age estimate and dispersion (months): mean (SD) or median (IQR) | Female proportion (%) |

| All admissions/unspecified infectious admissions | |||||||||

| Veirum et al 8 | January 1991–December 1996 | Guinea-Bissau | Prospective cohort | National Referral Hospital | All admissions | 3373 | <6 y | ||

| Moisi et al 9 | January 2004–December 2008 | Kenya | Retrospective cohort | District Hospital | All admissions | 10 277 | <15 y | ||

| Wiens et al 10 | March 2012–December 2013 | Uganda | Prospective cohort | Regional Referral Hospital | Proven or suspected infection | 1307 | 6 m-5 y | 18.10 (10.8–34.6) | 45.1 |

| Malnutrition | |||||||||

| Hennart et al 14 | 1970 | Democratic Republic of the Congo (Zaire) | Prospective cohort | Hospital | Severe protein-energy malnutrition | 171 | 0–6+ y | Mean=46 | |

| Kerac et al 12 | July 2006–March 2007 | Malawi | Prospective cohort | National Referral Hospital | Malnutrition | 1024 | 5–168 m | 21.5 (15.0–32.0) | 47 |

| Chisti et al 13 | April 2011–June 2012 | Bangladesh | Prospective cohort | Hospital | Severe malnutrition and radiological pneumonia | 405 | 0–59 m | 10 (5–18) | 44.2 |

| Berkley et al 15 | November 2009–March 2013 | Kenya | RCT | Hospital | Severe acute malnutrition—cotrimoxazole | 887 | 2–59 m | 11.2 (7.2–16.7) | 50% |

| Severe acute malnutrition—placebo | 891 | 10.8 (6.9–16.7) | 48% | ||||||

| Grenov et al 32 | March 2014–October 2015 | Uganda | RCT | National Referral Hospital | Severe acute malnutrition—probiotics | 200 | 6–59 m | 17.5 (8.5) | 42.5 |

| Severe acute malnutrition—placebo | 200 | 16.5 (8.4) | 42.5 | ||||||

| Respiratory Infection | |||||||||

| West et al 33 | May 1992–November 1994 | The Gambia | Case-control | Hospital | Acute lower respiratory tract infection | 118 | <5 y | Mean=9.7 | 43.2 |

| Villamor et al 17 | 1993–1997 | Tanzania | Prospective cohort | Hospital | Pneumonia | 687 | 6–60 m | 17.6 (12.1) | 45.8 |

| Ashraf et al 34 | September 2006–November 2008 | Bangladesh | Prospective cohort | Hospital | Severe pneumonia | 180 | 2–59 m | 7.3 (6.8) | 34.4 |

| Reddy et al 35 | November 2008–July 2009 | Tanzania | RCT | Regional Referral Hospital | Tuberculosis—standard diagnostics | 10 | <6 y | 21 (5–47) | 70 |

| Tuberculosis—intensified diagnostics | 13 | 10.5 (6.0–18.0) | 38.5 | ||||||

| Chhibber et al 16 | May 2008–May 2012 | The Gambia | Prospective cohort | Health Centre | Pneumonia, sepsis or meningitis | 3952 | 2–59 m | ||

| Ngari et al 18 | January 2007–December 2012 | Kenya | Prospective cohort | District Hospital | Severe pneumonia | 2461 | 1–59 m | 9.3 (3.9–20.4) | 43.2 |

| No pneumonia | 5270 | 19.5 (11.0–28.5) | 43.6 | ||||||

| Newberry et al 36 | April 2012–August 2014 | Malawi | RCT | Hospital | Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PJP)—intervention (corticosteroids) | 36 | 2–6 m | 3.1 (2.7–3.9) | 66.7 |

| PJP—placebo | 42 | 3.4 (2.9–4.4) | 50 | ||||||

| Diarrhoea | |||||||||

| Roy et al 19 | 1979–1980 | Bangladesh | Prospective cohort | Health Centre | Diarrhoea | 551 | 3–36 m | ||

| Stanton et al 37 | October 1983–December 1983 | Bangladesh | Retrospective cohort | Hospital | Diarrhoea | 112 | 24–72 m | 27 | |

| Islam et al 20 | November 1991–December 1992 | Bangladesh | Prospective cohort | Hospital | Diarrhoea | 427 | 1–23 m | 39.1 | |

| Anaemia/Malaria | |||||||||

| Zucker et al 24 | March 1991–September 1991 | Kenya | Case-control | District Hospital | Anaemia (case) | 293 | <60 m | 9.8 (8.6) | 50 |

| No anaemia (control) | 291 | 13.5 (11.3) | 50 | ||||||

| Biai et al 21 | December 2004–January 2006 | Guinea-Bissau | RCT | National Referral Hospital | Malaria—intervention | 460 | 3–60 m | 24 (13–36) | 45.4 |

| Malaria—no intervention | 491 | 24 (14–39) | 43 | ||||||

| Phiri et al 25 | July 2002–July 2004 | Malawi | Longitudinal case-control | Hospital | Severe anaemia | 377 | 6–60 m | 20.4 (12.8) | 53.6 |

| No anaemia | 377 | 22.5 (12.1) | 47.7 | ||||||

| Phiri et al 23 | June 2006– August 2009 | Malawi | RCT | Hospital | Severe malarial anaemia | 1414 | 4–59 m | 23.9 (13.4) | 51.6 |

| Olupot-Olupot et al 26 | 2014 | Uganda | RCT | Hospital | Severe anaemia—higher blood transfusion volume (30 mL/kg) | 78 | 60 d–12 y | 31 (11–48) | 51 |

| Severe anaemia—standard blood transfusion volume (20 mL/kg) | 82 | 36 (19–54) | 50 | ||||||

| Opoka et al 22 | November 2008–October 2013 | Uganda | Prospective cohort | National Referral Hospital | Cerebral malaria | 269 | 18 m–12 y | 3.9 (2.7–6.0) | 35.2 |

| Severe malarial anaemia | 233 | 2.8 (2.1–3.9) | 39.9 | ||||||

d, day; m, month; RCT, randomised controlled trial; y, year.

All admissions, including unspecified infectious admissions

The three studies within this population were conducted between 1991 and 2013 in Guinea-Bissau, Kenya and Uganda, and enrolled between 1307 and 10 277 subjects (table 2).8–10 Follow-up periods ranged from 6 months to 1 year, with postdischarge mortality ranging from 4.9% to 8% (table 3). Two studies reported postdischarge readmission, measured rates between 16.5% and 17.7%.9–11 Inpatient mortality was recorded by two studies, finding rates of 4.9% and 15%.8 10 These same studies recorded that most postdischarge deaths (67% and 77%) occurred outside of the hospital setting. The majority of postdischarge deaths occurred relatively early in the follow-up period, with 63% occurring within 13 (of 52) weeks in one study and 50% within 8 (of 24) weeks in the other study.8 10 Several variables were included in risk factor analyses for postdischarge mortality (table 4). Increasing age was shown to be a protective factor in all three studies. Parasitaemia was found to be associated with lower PDM compared with other diagnoses in two studies, with the third study showing lower PDM compared with diarrhoea, anaemia and other less common diagnoses. Bacteraemia, severe or very severe pneumonia, severe malnutrition, meningitis and HIV were all associated with a higher probability of postdischarge death.9 10 In the study by Veirum et al that evaluated discharge against medical advice (AMA), those who left AMA were eight times more likely to die after discharge.8 Anthropometric factors (including mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC), weight-for-age, weight-for-height and height-for-age z-scores), hypoxia, respiratory rate, jaundice, hepatomegaly and Blantyre coma scale rating were all associated with a statistically significant increase in the probability of PDM.9 10 Those who had been hospitalised prior to the index admission were also at increased risk for death, with each additional hospitalisation compounding the risk.9 10

Table 3.

Outcome characteristics

| Author ID | Intervention/Exposure | IPM (%)* | Follow-up times | Loss to follow-up (%)* | PD rehospitalised (%)* | PDM (%)* | Place of PD death | PDM statistics† |

| All admissions/unspecified infectious admissions | ||||||||

| Veirum et al 8 | 15 | Days 1, 14, 30, 91, 182, 365 | – | 8 | 77% at home 23% in hospital |

63% at 13 w | ||

| Moisi et al 9 | – | 1 year | – | 17.7 | 5.2 | |||

| Wiens et al 10 | 4.9 | 2, 4, 6 months | 1.7 | 16.5 | 4.9 | 67% out of hospital 33% in hospital |

50% at 4 w | |

| Malnutrition | ||||||||

| Hennart et al 14 | – | Every year for 5 years | – | 15.9 | 59% at 52 w | |||

| Kerac et al 12 | 23.2 | 90 days and 1 year | 17.2 | 6.62 | 24.0 | 44% at 13 w | ||

| Chisti et al 13 | 8.6 | Weekly for 2 weeks then monthly until 6 months | 15.0 | 8.7 | 80% at home 16% in hospital 4% on transport |

59% at 4 w 88% at 9 w |

||

| Berkley et al 15 | Oral cotrimoxazole prophylaxis | 3.4 | Once per month until 6 months, then once every 2 months until 12 months | 5.3 | 296 non-fatal admissions | 11.1 | (32%) in readmission to a study hospital (15%) in other hospitals (53%) in the community |

|

| Placebo | 5.1 | 320 non-fatal admissions | ||||||

| Grenov et al 32 | Probiotics | 11.5 | At 8–12 weeks | 10.4 | 1.8 | |||

| Placebo | 8.0 | 7.9 | 2.4 | |||||

| Respiratory infection | ||||||||

| West et al 33 | Hypoxaemia | – | Mean length of follow-up 41 months | 36.1 | 9.6 | |||

| Non-hypoxaemic | – | Mean length of follow-up 34.1 months | 39.3 | 3.7 | ||||

| Villamor et al 17 | 3.1 | Every 2 weeks for a year then every 4 months Mean duration of follow-up 24.7 months (SD=12.3, median=28.2) |

11.4 | 10.4 | 80% by 52 w | |||

| Ashraf et al 34 | 0 | Every 2 weeks for 3 months | 6.4 | 6.4 | 1.7 | |||

| Reddy et al 35 | Standard and intensified diagnostic arms analysed together | – | 2 and 8 weeks post-enrolment | – | 17.4 | 50% at 2 w ‘postenrolment deaths’; IP or PD not specified |

||

| Chhibber et al 16 | 3.9 | 180 days | – | 2.8 | 55% at 6 w | |||

| Ngari et al 18 | Pneumonia | 5.6 | Every 4 months until 1 year | 1.9 | 3.1 | 37% in hospital | 44% at 13 w 74% at 26 w |

|

| No pneumonia | 2.4 | 0.9 | 1.3 | |||||

| Newberry et al 36 | Corticosteroids | 27.8 | 1, 3, 6 months | 11.5 | 19.2 | |||

| Placebo | 52.4 | 10.0 | 35.0 | |||||

| Diarrhoeal diseases | ||||||||

| Roy et al 19 | – | Monthly for 12 months | – | 4 | 52% at 4 w 70% at 9 w |

|||

| Stanton et al 37 | 1.8 | At 4–5 months | 6.8 | 2.9 | ||||

| Islam et al 20 | 14.6 | At 6 and 12 weeks | – | 7.5 | 94% at 6 w | |||

| Anaemia/Malaria | ||||||||

| Zucker et al 24 | Anaemia | 13 | 4 and 8 weeks | 4.0 | 18.8 | |||

| No anaemia; figures include the analysed ‘no-anaemia cohort’ from study plus additional children | 9 | 4.0 | 10.3 | |||||

| Biai et al 21 | Intervention: improved management and free emergency drugs for malaria, financial incentive | 4.6 | 28 days | 3.9 | 1.8 | |||

| Control | 9.4 | 4.9 | 0.9 | |||||

| Phiri et al 25 | Severe anaemia | 6.4 | 1, 3, 6, 12, 18 months | 17.8 | 18.1 | 11.6 | 71% at 26 w | |

| No anaemia | 0 | 19.6 | 9.3 | 2.7 | 60% at 26 w | |||

| Phiri et al 23 | Artemether–lumefantrine | – | 1, 3, 6 months | 5.0 | 21.5 | 2.5 | 50% at 4 w | |

| Placebo | – | 4.9 | 24.4 | 2.3 | 50% at 9 w | |||

| Olupot-Olupot et al 26 | Severe anaemia—higher blood transfusion volume (30 mL/kg) | 0 | 28 days postadmission | 0 | 1.3 | |||

| Severe anaemia—standard blood transfusion volume (20 mL/kg) | 7.3 | 0 | 0 | |||||

| Opoka et al 22 | Cerebral malaria | 12.6 | 6 months | 2.5 | 3.1 | 0.6 | ||

| Severe malarial anaemia | 0.4 | 3.6 | 9.4 | 2.2 | ||||

*Indicates cumulative rates as of the last follow-up time.

†Indicates specified mortality statistics in regard to per cent of total postdischarges by a certain number of weeks, in relation to entire duration of follow-up.

IP, inpatient; IPM, inpatient mortality; PD, postdischarge; PDM, postdischarge mortality; w, week.

Table 4.

Risk factors for PDM in all admissions/unspecified infectious admission studies

| Article | Risk factor category | Mortality risk factor on admission | Estimate type | Estimate (95% CI) | Adjusted |

| Veirum et al 8 | Age | Age at discharge>5 years (ref: age 1–12 months) | RR | 0.15 (0.07 to 0.30) | Yes |

| Age at discharge 4 years (ref: age 1–12 months) | RR | 0.23 (0.10 to 0.59) | Yes | ||

| Age at discharge 3 years (ref: age 1–12 months) | RR | 0.14 (0.06 to 0.35) | Yes | ||

| Age at discharge 2 years (ref: age 1–12 months) | RR | 0.52 (0.33 to 0.81) | Yes | ||

| Age at discharge 1 year (ref: age 1–12 months) | RR | 0.82 (0.59 to 1.13) | Yes | ||

| Neonatal (ref: age 1–12 months) | RR | 0.69 (0.31 to 1.55) | Yes | ||

| Diagnosis | Diagnosis: other—includes chronic diseases which cannot be treated in Bissau (ref: malaria) | RR | 1.65 (1.08 to 2.55) | Yes | |

| Anaemia (ref: malaria) | RR | 1.97 (1.07 to 3.63) | Yes | ||

| Diarrhoea (ref: malaria) | RR | 1.82 (1.21 to 2.74) | Yes | ||

| Bronchopneumonia (ref: malaria) | RR | 0.98 (0.65 to 1.51) | Yes | ||

| Measles (ref: malaria) | RR | 0.77 (0.36 to 1.64) | Yes | ||

| Hospital stay | Leaving against medical advice | RR | 8.51 (5.32 to 13.59) | Yes | |

| Maternal influence | Mother educated (ref: no maternal education) | RR | 0.74 (0.55 to 0.99) | Yes | |

| Moisi et al 9 | Age | Age 1–5 months | HR | 1.34 (0.93 to 1.92) | Yes |

| Age 6–11 months | HR | 0.82 (0.57 to 1.18) | Yes | ||

| Age 2–5 years | HR | 0.57 (0.36 to 0.90) | Yes | ||

| Sick young infant | HR | 2.67 (1.98 to 3.58) | Yes | ||

| Diagnosis | Parasitaemia | HR | 0.45 (0.29 to 0.71) | Yes | |

| Bacteraemia | HR | 1.77 (1.15 to 2.74) | Yes | ||

| Mild pneumonia | HR | 2.30 (1.00 to 5.28) | Yes | ||

| Severe pneumonia | HR | 1.37 (1.05 to 1.79) | Yes | ||

| Very severe pneumonia | HR | 4.09 (2.25 to 7.46) | Yes | ||

| Severe malnutrition | HR | 4.37 (2.73 to 7.01) | Yes | ||

| Meningitis | HR | 2.29 (1.57 to 3.32) | Yes | ||

| Growth parameters | WAZ < −3 | HR | 3.42 (2.50 to 4.68) | Yes | |

| WAZ < −4 | HR | 6.53 (4.85 to 8.80) | Yes | ||

| Hospital stay | Hospitalisation>13 days | HR | 1.83 (1.33 to 2.52) | Yes | |

| One prior discharge (occurring within 1 year of index discharge) | HR | 2.83 (2.04 to 3.92) | Yes | ||

| Two prior discharges | HR | 7.06 (4.09 to 12.21) | Yes | ||

| ≥3 prior discharges | HR | 23.55 (10.70 to 51.84) | Yes | ||

| Symptoms | Hypoxia | HR | 2.30 (1.64 to 3.23) | Yes | |

| Jaundice | HR | 1.77 (1.08 to 2.91) | Yes | ||

| Hepatomegaly | HR | 2.34 (1.60 to 3.24) | Yes | ||

| Wiens et al 10 2015 | Age | Age (months) | OR | 0.97 (0.97 to 0.97) | No |

| Comorbid conditions | HIV positive | OR | 5.21 (2.55 to 10.65) | No | |

| Growth parameters | MUAC (mm) | OR | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.98) | No | |

| Weight-for-age z-score | OR | 0.66 (0.57 to 0.76) | No | ||

| Weight for length/height z-score | OR | 0.81 (0.72 to 0.91) | No | ||

| Length/height-for-age z-score | OR | 0.79 (0.70 to 0.89) | No | ||

| Hospital stay | Illness>7 days prior to admission | OR | 0.50 (0.30 to 0.83) | No | |

| Time since last hospitalisation (ordered as <7 days, 7–30 days, 30 days to 1 year, >1 year and never (analysed as continuous and coded as 1–5, respectively) | OR | 0.75 (0.62 to 0.90) | No | ||

| Labs/Assessments | Haemoglobin (g/dL) | OR | 0.95 (0.87 to 1.03) | No | |

| Blantyre coma scale<5 (ref: 5) | OR | 2.40 (1.27 to 4.57) | No | ||

| Positive blood smear | OR | 0.33 (0.16 to 0.68) | No | ||

| Maternal influence | Maternal age (years) | OR | 1.00 (0.97 to 1.04) | No | |

| Maternal HIV positive (ref: HIV negative) | OR | 1.79 (0.87 to 3.67) | No | ||

| Maternal HIV status unknown (ref: HIV negative) | OR | 1.27 (0.64 to 2.52) | No | ||

| Maternal education primary 3–7 (ref: maternal education<P3) | OR | 1.18 (0.62 to 2.23) | No | ||

| Maternal education some secondary (ref: maternal education<P3) | OR | 0.72 (0.31 to 1.70) | No | ||

| Maternal education postsecondary (ref: maternal education<P3) | OR | 1.18 (0.41 to 3.36) | No | ||

| Sex | Male | OR | 0.90 (0.54 to 1.51) | No | |

| Social determinants of health | Bed net use—sometimes (ref: never) | OR | 1.00 (0.48 to 2.09) | No | |

| Bed net use—always (ref: never) | OR | 0.85 (0.46 to 1.58) | No | ||

| Siblings death | OR | 1.54 (0.89 to 2.65) | No | ||

| Number of children in the family | OR | 1.02 (0.92 to 1.13) | No | ||

| Boil all drinking water | OR | 0.82 (0.47 to 1.42) | No | ||

| Distance from hospital 30–60 min (ref: distance<30 min) | OR | 0.71 (0.31 1.64) | No | ||

| Distance from hospital>60 min (ref: distance<30 min) | OR | 1.30 (0.70 to 2.41) | No | ||

| Vital signs | HR for age z-score | OR | 0.86 (0.74 to 0.99) | No | |

| HR (raw) | OR | 1.00 (0.99 to 1.01) | No | ||

| RR for age z-score | OR | 0.99 (0.92 to 1.06) | No | ||

| RR (raw) | OR | 1.01 (1.00 to 1.03) | No | ||

| SBP z-score | OR | 0.94 (0.79 to 1.12) | No | ||

| SBP (raw) | OR | 0.98 (0.96 to 1.00) | No | ||

| DBP (raw) | OR | 0.99 (0.97 to 1.01) | No | ||

| Temperature (transformed) | OR | 1.02 (0.90 to 1.16) | No | ||

| Temperature (raw) | OR | 0.76 (0.62 to 0.93) | No | ||

| SpO2 (raw) | OR | 0.94 (0.92 to 0.96) | No | ||

| SpO2 (transformed) | OR | 1.04 (1.02 to 1.05) | No |

Bolded values are statistically significant.

DBP, diastolic blood pressure; PDM, postdischarge mortality; RR, relative risk; SBP, systolic blood pressure; WAZ, weight for age z-score.

Malnutrition

Five studies focusing on a malnourished population were identified. These studies were conducted in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Malawi, Bangladesh, Kenya and Uganda between 1970 and 2015 and and enrolled between 171 and 1778 children (table 2). The period of follow-up varied widely in this subpopulation, ranging from 8 weeks to 5 years (table 3). Postdischarge mortality rates were observed to be between 1.8% and 24%. Where hospital mortality rates were measured (n=2), mortality following discharge was comparable to that observed during hospital admission, with one study reporting an inpatient mortality rate of 23.2% (24% after discharge), and a second study of 8.6% (8.7% after discharge).12 13 Three of four studies specified the timing of deaths during the follow-up period with all finding that the majority of deaths following discharge occurred early during the follow-up period (relative to total follow-up). In one study, 59% of those who died after discharge did so within 52 weeks (of 5 years),14 another found that 44% died within 13 (of 52) weeks,12 and the third study observed 88% dying within 9 (of 26) weeks of discharge.13 A study conducted in Bangladesh reporting the location of postdischarge death found that 80% of deaths occurred at home, while another conducted in Kenya found 53% occurring in the community.13 15 Anthropometric parameters including MUAC, weight-for-age and weight-for-height z-scores were among the highly significant predictors for death postdischarge (table 5).12 13 Age <12 months was associated with mortality in one study, but was found not to be significant in another, although wide CIs could not rule out an important effect.12 13 Highly significant associations variables included positive HIV status (HR 4.03; 95% CI 3.08 to 5.25), unknown HIV status (HR 16.90; 95% CI 12.10 to 23.70) and discharge AMA (HR 4.68; 95% CI 2.01 to 10.85).

Table 5.

Risk factors for PDM in malnutrition studies

| Article | Risk factor category | Mortality risk factor on admission | Estimate type | Estimate (95% CI) | Adjusted |

| Hennart et al 14 | No data | ||||

| Kerac et al 12 | Age | Age>60 m (ref: age 48–60 m) | HR | 1.22 (0.63 to 2.36) | Yes |

| Age 36–48 m (ref: age 48–60 m) | HR | 1.66 (0.84 to 3.29) | Yes | ||

| Age 24–36 m (ref: age 48–60 m) | HR | 1.38 (0.76 to 2.49) | Yes | ||

| Age 12–24 m (ref: age 48–60 m) | HR | 1.57 (0.89 to 2.78) | Yes | ||

| Age<12 m (ref: age 48–60 m) | HR | 2.49 (1.38 to 4.51) | Yes | ||

| Comorbid conditions | HIV positive (ref: HIV negative) | HR | 4.03 (3.08 to 5.25) | Yes | |

| HIV unknown status (ref: HIV negative) | HR | 16.90 (12.10 to 23.70) | Yes | ||

| Growth parameters | Oedema | HR | 0.58 (0.47 to 0.72) | Yes | |

| MUAC per cm unit increase | HR | 0.80 (0.74 to 0.86) | Yes | ||

| Weight-for-height: per 1 unit z-score increase | HR | 0.75 (0.68 to 0.83) | Yes | ||

| Weight-for-age: per 1 unit z-score increase | HR | 0.73 (0.66 to 0.81) | Yes | ||

| Height-for-age: per 1 unit z-score increase | HR | 0.92 (0.86 to 0.99) | Yes | ||

| Sex | Male | HR | 0.89 (0.73 to 1.08) | Yes | |

| Chisti et al 13 | Age | Age<12 m | OR | 2.05 (0.90 to 4.90) | No |

| Comorbid conditions | Confirmed TB | OR | 1.74 (0.40 to 6.90) | No | |

| Clinical TB—not confirmed | OR | 0.15 (0.01 to 1.10) | No | ||

| History of previous pneumonia prior to present episode | OR | 3.4 (1.1 to 10.2) | No | ||

| Growth parameters | Severe wasting* (z-score <−4 weight-for-height/length) | OR | 3.4 (1.5 to 7.8) | No | |

| Severe underweight* (z-score <−5 weight-for-age) | OR | 3.05 (1.4 to 6.8) | No | ||

| Severe wasting (z-score <−4 weight-for-height/length) | OR | 2.74 (1.2 to 6.2) | No | ||

| Severe underweight (z-score <−5 weight-for-age) | OR | 2.82 (1.2 to 6.7) | No | ||

| Nutritional oedema | OR | 2.34 (0.5 to 9.6) | No | ||

| Hospital stay | Left against medical advice* | OR | 4.16 (1.5 to 11.3) | No | |

| Sex | Male | OR | 0.68 (0.3 to 1.5) | No | |

| Social determinants of health | Live outside Dhaka district | OR | 1.69 (0.7 to 4) | No | |

| Poor socioeconomic condition−income<US$125 per month | OR | 0.73 (0.3 to 2) | No | ||

| Symptoms | Lower chest wall in-drawing | OR | 0.86 (0.4 to 1.9) | No | |

| Hypoxaemia (arterial oxygen saturation<90% in room air) | OR | 1.23 (0.3 to 4.7) | No | ||

| Berkley et al 15 | Intervention | Cotrimoxazole vs placebo | HR | 0.90 (0.71 to 1.16) | No |

| Grenov et al 32 | No data | ||||

Bolded values are statistically significant.

*Risk factor for mortality assessed on discharge.

m, month; PDM, postdischarge mortality; TB, tuberculosis.

Respiratory infection

Seven studies examining respiratory infections were identified. These included children with a variety of inclusion criteria, including pneumonia, acute lower respiratory tract infection and tuberculosis. Studies were conducted between 1992 and 2014 in the Gambia, Tanzania, Bangladesh, Malawi and Kenya (table 2). Mortality rates postdischarge ranged widely, from 1.3% to 35% across the studies. These rates, however, remained consistently comparable to inpatient mortality when both were measured (table 3). As with other populations, mortality rates generally occurred early during follow-up. A large prospective cohort study by Ngari et al including children aged 1–59 months with severe pneumonia found that 74% of postdischarge deaths occurred by 26 (of 52) weeks with 63% occurring outside of the hospital. Chhibber et al 16 conducted a study of 3952 children admitted primarily with pneumonia in rural Gambia, and sought to identify specific comorbidities and physiologic factors predictive of mortality after discharge. This study found that physiologic factors, including neck stiffness, oxygen saturation, temperature and haemoglobin concentration were associated with postdischarge mortality. Malnutrition-related variables (clinical malnutrition and low MUAC) were the strongest predictors of postdischarge mortality, producing HRs ranging from 18.4 to 43.7 (table 6). Although individual studies differed in regard to whether risk factors were measured continuously, categorically or dichotomously, it is clear that the directionality of certain risk factors such as low haemoglobin and low MUAC continue to be associated with higher PDM in children admitted for respiratory illness.16–18 When examining the timing of mortality, most cases occurred relatively early during follow-up. One study found that 80% had occurred by 12 months (mean duration of follow-up 24.7 months),17 another study had 55% by 6 (of 26) weeks16 and yet another reported 74% by 26 (of 52) weeks.18 Low MUAC, stunting, HIV-positive status, jaundice, low haemoglobin, under 24 months of age and availability of water were significant predictors of postdischarge mortality among children with respiratory illness.17 18

Table 6.

Risk factors for PDM in respiratory infection studies

| Article | Risk factor category | Mortality risk factor on admission | Estimate type | Estimate (95% CI) | Adjusted |

| West et al 33 | No data | ||||

| Villamor et al 17 | Age | Age 6–11 m (ref: >24 m) | HR | 3.70 (1.72 to 7.95) | Yes |

| Age 12–23 m (ref: >24 m) | HR | 3.14 (1.44 to 6.88) | Yes | ||

| Comorbid conditions | HIV positive | HR | 3.92 (2.34 to 6.55) | Yes | |

| Diagnosis | Severe pneumonia on admission | HR | 2.47 (1.59 to 3.85) | Yes | |

| Growth parameters | Stunted at baseline (2 z-scores (NCHS/WHO reference) in height-for-age Wasted children were 2 z-scores in weight-for-height) | HR | 2.12 (1.31 to 3.42) | Yes | |

| Low MUAC at baseline (25th percentile of the population age-specific distribution) | HR | 1.88 (1.16 to 3.03) | Yes | ||

| Labs/Assessments | Haemoglobin (Hgb) concentration<7.00 (g/dL) (ref: Hgb concentration>10 g/dL) | HR | 2.55 (1.13 to 5.77) | Yes | |

| Hgb concentration 7.01–8.50 g/dL (ref: Hgb concentration>10 g/dL) | HR | 2.81 (1.24 to 6.37) | Yes | ||

| Hgb concentration 8.51–10.00 g/dL (ref: Hgb concentration>10 g/dL) | HR | 1.76 (0.75 to 4.10) | Yes | ||

| Maternal influence | Maternal education—elementary (ref: no maternal education) | HR | 0.84 (0.48 to 1.49) | Yes | |

| Maternal education—secondary or higher (ref: no maternal education) | HR | 0.27 (0.06 to 1.17) | Yes | ||

| Mother works outside home | HR | 0.61 (0.36 to 1.03) | Yes | ||

| Mother not living with partner | HR | 1.60 (1.00 to 2.57) | Yes | ||

| Sex | Male | HR | 0.98 (0.65 to 1.48) | Yes | |

| Social determinants of health | Water tap in compound (ref: water tap in house) | HR | 1.40 (0.60 to 3.29) | Yes | |

| Water tap outside compound (ref: water tap in house) | HR | 2.27 (1.02 to 5.03) | Yes | ||

| Public well (ref: water tap in house) | HR | 2.92 (1.03 to 8.30) | Yes | ||

| Ashraf et al 34 | No data | ||||

| Reddy et al 35 | Intervention | Not receiving anti-TB medication (predictor of death within 2 weeks of admission) | OR | 0.25 (0.03 to 2.00) | No |

| Not receiving anti-TB medication (predictor of death within 8 weeks of admission) | OR | 0.20 (0.04 to 0.96) | No | ||

| Chhibber et al 16 | Age | Age (m) | HR | 1.00 (0.98 to 1.03) | Yes |

| Comorbid conditions | Sepsis with clinically severe malnutrition (CSM); (ref: pneumonia without CSM) | HR | 18.4 (11.3 to 30.0) | Yes | |

| Meningitis with CSM (ref: pneumonia without CSM) | HR | 13.7 (4.2 to 44.7) | Yes | ||

| Pneumonia with CSM (ref: pneumonia without CSM) | HR | 8.1 (4.4 to 14.8) | Yes | ||

| Meningitis without CSM (ref: pneumonia without CSM) | HR | 2.6 (1.2 to 5.5) | Yes | ||

| Sepsis without CSM (ref: pneumonia without CSM) | HR | 2.2 (1.1 to 4.3) | Yes | ||

| Growth parameters | MUAC 11.5–13.0 cm (ref: MUAC>13 cm) | HR | 7.19 (3.04 to 17.01) | Yes | |

| MUAC 10.5–11.4 cm (ref: MUAC>13 cm) | HR | 24.2 (9.4 to 61.9) | Yes | ||

| MUAC<10.5 cm (ref: MUAC>13 cm) | HR | 43.7 (17.7 to 108.0) | Yes | ||

| Hospital stay | Non-medical discharge | HR | 4.68 (2.01 to 10.85) | Yes | |

| Labs/Assessments | Hgb concentration (g/dL) | HR | 0.82 (0.73 to 0.91) | Yes | |

| Social determinants of health | Dry season | HR | 1.96 (1.16 to 3.32) | Yes | |

| Sym | Neck stiffness | HR | 10.4 (3.1 to 34.8) | Yes | |

| Vital signs | Axillary temperature (°C) | HR | 0.71 (0.58 to 0.87) | Yes | |

| SpO2 (%) | HR | 0.96 (0.93 to 0.99) | Yes | ||

| Ngari et al 18 | Age | Age 12–23 m (ref: age>24 m) | HR | 1.0 (0.1 to 9.6) | Yes |

| Age 6–11 m (ref: age>24 m) | HR | 5.8 (0.8 to 40.5) | Yes | ||

| Age<6 m (ref: age>24 m) | HR | 4.8 (0.7 to 34.1) | Yes | ||

| Comorbid conditions | Reported preterm/low birth weight | HR | 0.7 (0.2 to 2.8) | Yes | |

| HIV antibody test positive | HR | 6.5 (2.3 to 18.4) | Yes | ||

| HIV test not performed | HR | 0.4 (0.1 to 3.6) | Yes | ||

| RSV test positive | HR | 0.3 (0.1 to 1.2) | Yes | ||

| RSV test not performed | HR | 2.7 (1.2 to 6.3) | Yes | ||

| Malaria slide positive | HR | 0.5 (0.1 to 5.2) | Yes | ||

| Bacteraemia | HR | 0.8 (0.1 to 5.2) | Yes | ||

| Growth parameters | MUAC per cm | HR | 0.6 (0.5 to 0.8) | Yes | |

| Hospital stay | Duration of hospitalisation (per day) | HR | 1.1 (1.0 to 1.2) | Yes | |

| Hospital stay | Year of admission 2008 (ref: 2007 admission year) | HR | 0.9 (0.3 to 3.1) | Yes | |

| Year of admission 2009 (ref: 2007 admission year) | HR | 0.5 (0.1 to 2.1) | Yes | ||

| Year of admission 2010 (ref: 2007 admission year) | HR | 0.7 (0.2 to 2.5) | Yes | ||

| Year of admission 2011 (ref: 2007 admission year) | HR | 1.7 (0.5 to 5.3) | Yes | ||

| Year of admission 2012 (ref: 2007 admission year) | HR | 1.8 (0.2 to 15.7) | Yes | ||

| Labs/Assessments | Severe anaemia (Hgb<5 g/dL) | HR | 0.8 (0.1 to 7.5) | Yes | |

| Sex | Female | HR | 0.5 (0.3 to 1.1) | Yes | |

| Social determinants of health | Residence distance from hospital (per km) | HR | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) | Yes | |

| Symptoms | Capillary refill>2 s | HR | 2.4 (0.5 to 12.1) | Yes | |

| Impaired consciousness | HR | 1.1 (0.2 to 7.8) | Yes | ||

| Wheezing | HR | 0.5 (0.1 to 2.4) | Yes | ||

| Cough for>14 days | HR | 0.2 (0.1 to 5.5) | Yes | ||

| Jaundice | HR | 12.5 (1.1 to 13.7) | Yes | ||

| Vital signs | Hypoxia (SaO2<90%) | HR | 1.9 (0.7 to 5.4) | Yes | |

| Axillary temperature<36°C (ref: axillary temperature 36°C–39°C) | HR | 0.3 (0.1 to 2.8) | Yes | ||

| Axillary temperature>39°C (ref: axillary temperature 36°C–39°C) | HR | 1.1 (0.4 to 3.0) | Yes | ||

| Newberry et al 36 | Intervention | Prednisone (ref: placebo) | RR | 0.63 (0.41 to 0.95) | |

Bolded values are statistically significant.

m, month; NCHS, National Center for Health Statistics; PDM, postdischarge mortality; RR, relative risk; TB, tuberculosis.

Diarrhoeal diseases

Three studies of paediatric patients with diarrhoea conducted between 1979 and 1992 were included, all three of which were conducted in Bangladesh (table 2). Included studies enrolled children aged 1–72 months and found postdischarge death rates of between 2% and 8%, all being generally comparable to in-hospital rates (table 3). Deaths occurred within the first few weeks after discharge, with one study reporting 52% by 4 (of 52) weeks,19 and a second reporting 94% of deaths occurring by 6 (of 12) weeks postdischarge.20 Significant risk factors for death after discharge identified in this set of studies included young age (<6 months), not having been breast fed, malnutrition (based on Height for age z-score (HAZ) and WAZ scores), low levels of maternal education and immunisation status of the child (table 7).

Table 7.

Risk factors for PDM in diarrhoea studies

| Article | Risk factor category | Mortality risk factor on admission | Estimate type | Estimate (95% CI) | Adjusted |

| Roy et al 19 | No data | ||||

| Stanton et al 37 | No data | ||||

| Islam et al 20 | Age | Age<6 months | RR | 4.57 (2.90 to 7.18) | Yes |

| Growth parameters | Weight-for-age median<60% | RR | 1.04 (0.57 to 1.89) | Yes | |

| Length-for-age median<85% | RR | 2.97 (1.43 to 6.16) | Yes | ||

| Maternal influence | Mother’s education (no school vs >1 year) | RR | 2.12 (1.37 to 3.28) | Yes | |

| No breast feeding | RR | 2.35 (1.44 to 3.84) | Yes | ||

| Sex | Female | RR | 1.73 (1.14 to 2.65) | Yes | |

| Social determinants of health | Immunisation not up-to-date | RR | 1.36 (1.25 to 1.48) | Yes | |

Bolded values are statistically significant.

PDM, postdischarge mortality; RR, relative risk.

Anaemia and/or malaria

Six studies were conducted between 1991 and 2014 in Kenya, Guinea-Bissau, Malawi and Uganda in children with anaemia and/or malaria (table 2). Studies were heterogeneous in their specified populations, including children with various illness severity, with mortality postdischarge ranging from 0.9% to 18.8%, and with follow-up periods ranging from 1 to 18 months (table 3). In the only study looking specifically at acute malaria, postdischarge mortality (1.8% intervention; 0.9%% control) was lower than inpatient mortality (4.6% intervention; 9.4% control) over a follow-up period of 28 days.21 Another study that followed children with cerebral malaria or severe malarial anaemia for 6 months following discharge reported that although children with cerebral malaria experienced higher inpatient mortality (13% compared with 0.4%), those with severe malarial anaemia had a higher rate of death after discharge (2.2% compared with 0.6%).22 A large study (n=1414) by Phiri et al examining severe malarial anaemia found high rates of postdischarge readmission (approximately 22%), with rates of death at approximately 2.4%.23 Children with anaemia experienced higher rates of inpatient (13% anaemia; 9% no anaemia) and postdischarge mortality (18.8% anaemia; 10.3% no anaemia).24 In both cohorts, death after discharge was greater than death in-hospital. Rates of readmission to hospital within 18 months were quantified in one study (18.4% severe anaemia; 9% no anaemia) and postdischarge mortality rates (11.6% anaemia; 2.7% no anaemia) exceed those of inpatient mortality rates (6.4% anaemia; 0% no anaemia).25 Although this study had approximately 18% loss to follow-up, 71% of anaemic and 60% of non-anaemic total postdischarge deaths had occurred by 26 (of 78) weeks.25 An RCT conducted in Uganda studied the effect of transfusion volume (30 mL/kg vs the standard 20 mL/kg) in severely anaemic children, which showed reduced inpatient mortality rates but no difference for deaths after discharge (table 8).26 Rates of death were consistently higher after discharge than in hospital in paediatric patients presenting with malaria and/or anaemia. Of risk factors identified throughout these studies, severe anaemia was found to be highly significant for postdischarge death24 and readmission to the hospital.22 HIV status profoundly influenced mortality, with a HR of 10.49 (95% CI 4.05 to 27.20) for death postdischarge in children who tested positive.25

Table 8.

Risk factors for PDM in anaemia/malaria studies

| Article | Risk factor category | Mortality risk factor on admission | Estimate type | Estimate (95% CI) | Adjusted |

| Biai et al 21 | No data | ||||

| Phiri et al 25 | Age | Age (months) | HR | 0.92 (0.87 to 0.97) | Yes |

| Comorbid conditions | HIV positive | HR | 10.49 (4.05 to 27.20) | Yes | |

| Bacteraemia | HR | 2.17 (0.84 to 5.64) | Yes | ||

| Diagnosis | Malaria (any parasite/mL blood) | HR | 1.25 (0.67 to 2.34) | No | |

| Growth parameters | Wasting (<−2 z-score weight-for-height) | HR | 0.74 (0.31 to 1.80) | No | |

| Stunting (<−2 z-score height-for-age) | HR | 0.61 (0.30 to 1.22) | No | ||

| Labs/Assessments | Iron deficiency (>5.6 sTfR/log ferritin) | HR | 0.91 (0.41 to 2.03) | No | |

| Maternal influence | Mother education (some) | HR | 1.63 (0.72 to 3.70) | No | |

| Sex | Male | HR | 1.54 (0.68 to 3.52) | Yes | |

| Social determinants of health | Rural residency | HR | 1.63 (0.63 to 4.20) | Yes | |

| Parents unemployed | HR | 4.15 (1.61 to 10.74) | Yes | ||

| Symptoms | Splenomegaly | HR | 0.36 (0.16 to 0.80) | Yes | |

| Phiri et al 23 | No data | ||||

| Zucker et al 24 | Intervention | PS, quinine, TS treatment x5d (ref: chloroquine or no antimalarial) | RR | 0.33 (0.19 to 0.65) | Unspecified |

| Labs/Assessments | Severe anaemia (Hgb<5 g/dL) | RR | 1.52 (1.22 to 1.90) | Unspecified | |

| Olupot-Olupot et al 26 | Intervention | 30 mL/kg transfusion vs 20 mL/kg transfusion | RR | 0.18 (0.02 to 1.42) | Unspecified |

| Opoka et al 22 | Diagnosis | Severe malarial anaemia* | HR | 16.26 (2.03 to 130.34) | Yes |

| Cerebral malaria* | HR | 4.45 (0.51 to 38.55) | Yes | ||

*Risk factor for readmission.

Hgb, haemoglobin; PDM, postdischarge mortality; RR, relative risk.

Discussion

Twenty-four studies examining postdischarge mortality in paediatric populations in developing countries were included in this systematic review, together substantiating the significant and unaddressed challenge continuing to plague children around the world. Significant heterogeneity in study characteristics was noted, within inclusion criteria, study design, length of follow-up, interventions (if any), risk factors and risk factor definitions. Studies were conducted primarily in African countries, and examined a variety of populations, including all admissions, infectious disease admissions, malnutrition, respiratory infections, diarrhoea, malaria and anaemia. Studies examining anaemia and/or malaria had the lowest PDM rates, while those of malnutrition and respiratory infections had the highest. Results from the studies identified through the updated search generally reflected the results from the earlier systematic review; rates of postdischarge mortality continued to be high and comparable to (sometimes exceeding) in-hospital mortality, with most postdischarge deaths occurring at home.5 With so many deaths occurring after discharge, it is critical that effective interventions be developed and evaluated as a means to addressing this neglected cause of childhood deaths. Furthermore, no analysis of cause for death postdischarge was identified within any of the reviewed studies, highlighting this as an important area for further research.

When reported, over two-thirds of postdischarge deaths were noted to occur outside of the hospital, generally at home. In order to develop interventions to reduce the burden of PDM, an understanding of circumstances and barriers to care following discharge is of utmost importance. In a recent qualitative study, mothers of children who died postdischarge identified barriers to seeking care prior to their child’s death; barriers included lack of access to health facilities and services, poor health-seeking behaviour, finances, transportation and a lack of recognition of symptoms and perceptions of recovery in children recently discharged even in the midst of persisting illness.27 Additional factors that contribute to poor socioeconomic conditions may relate to deaths after discharge, as they further disadvantage children and families. Socioeconomically disadvantaged children continue to be served by health sectors that are poorly resourced and lack the resilience to be able to deal with large numbers of patients seen every day. Follow-up care after initial hospitalisation is an important and yet largely ignored aspect of comprehensive healthcare in both developing countries.2 With so few patients returning to the healthcare system after discharge, identifying and understanding the barriers and targeted interventions required to enhance outcomes must be initiated during the original hospitalisation.

Risk factors consistently identified across all types of infectious admissions as highly associated with postdischarge mortality included HIV status, young age, pneumonia, malnutrition, anthropometric factors, hypoxia, anaemia, leaving the hospital against medical advice and previous hospitalisations. An important observation, therefore, is that regardless of the underlying infectious aetiology, certain risk factors consistently identify vulnerability. These observations suggest that vertical, disease-based, approaches to addressing postdischarge mortality are likely to be ineffective in comparison to simple, broadly applicable interventions. Specific illness (ie, pneumonia, diarrhoea, malaria) are often both difficult to differentiate clinically and often co-exist, especially in children in low-resource settings.28 Sepsis, therefore, as the final common pathway for the majority of infectious disease-related deaths, may be a helpful framework within which to explore paediatric postdischarge mortality and to develop interventions. Instead of focusing on a specific body system or infectious agent, pragmatic interventions towards time-sensitive treatment can be focused towards sepsis as the overarching syndrome, increasing the potential for impactful results.28 The Integrated Management of Childhood Illness (IMCI) pocketbook by the WHO uses a similar approach through their identification of danger signs and treatments as opposed to individual diseases. Addressing sepsis through clinical management is an important component in the reduction of preventable childhood death, requiring sustained efforts by the global community including healthcare providers, patients, pharmaceutical companies and policy makers if large-scale change is to occur.29

While knowledge of risk factors alone has only moderate utility in the identification of vulnerable children, the development of robust prediction models can provide a more reliable means of risk evaluation. In resource-limited environments, the use of prediction modelling is appealing, especially in relation to interventions aimed at improving postdischarge outcomes. A recent proof-of-concept study found that a simple discharge intervention including education and routine postdischarge follow-up could substantially improve postdischarge health seeking and health outcomes.30 Such approaches, if focused primarily on the most vulnerable children, can ensure that limited resources are most effectively used and have the highest possible level of cost-effectiveness.

This systematic review is subject to several important limitations. First, it is possible that some relevant articles may not have been identified through the systematic search. Although the search was comprehensive, including both Medline and EMBASE, no MeSH/Emtree terms currently exist for postdischarge mortality and even so, many studies measure postdischarge mortality as a secondary end point. A further limitation of this review is that the studies included were predominantly based in African countries. Therefore, these results may not be as applicable to countries outside of this setting. This highlights the continued need for ongoing research in resource-poor settings both within and outside of Africa. Significant heterogeneity in duration of follow-up, as well as when postdischarge mortality was assessed, was noted between the studies, potentially leading to a decreased ability to compare mortality rates. Many studies included in this review had high losses to follow-up (ranging between 0% and 39.3%), and very few were conducted prospectively with the stated intent of exploring postdischarge mortality. Studies with significant attrition due to follow-up likely underestimate the true rate of postdischarge mortality as these losses undoubtedly represent a more vulnerable population. While one study focused on barriers to care following discharge among those children who died in the community, one important remaining gap is that studies did not evaluate the causes of postdischarge mortality, which is difficult to measure given that most deaths occur in the community.10 27 The ongoing, multicountry, Childhood Acute Illness and Nutrition (CHAIN) network, is attempting to understand the specific reasons for deaths postdischarge among malnourished children.31 It is through contributions such as this that further interventions can be developed and implemented that target the specific and causal factors affecting paediatric mortality rates in developing countries.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the studies identified emphasise the significant burden of postdischarge mortality in countries where overextended and resource-limited health systems serve millions of socioeconomically disadvantaged children. The scale of this burden continues to be under-recognised, in part due to the inability of health systems to observe patient outcomes after discharge. Addressing these issues with specific regard to the identification of vulnerable children, and the development of effective postdischarge interventions, will be an essential component towards the achievement of the child mortality targets of the SDGs.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: BN: conceptualised and designed the review, carried out article analysis, drafted the initial manuscript, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. LE: contributed to analysis, reviewed and revised for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript as submitted. NK: contributed to conception and design, interpretation of data and reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript as submitted. JMA: contributed to conception and design, interpretation of data, reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript as submitted. PPM: contributed to interpretation of data, reviewed and revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript as submitted. JK: contributed to interpretation of data, reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. SF-K: contributed to interpretation of data, review and revision of manuscript for important intellectual content and approved the final manuscript as submitted. EK: contributed to interpretation of data, review and revision for intellectual content and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. MOW: conceptualised and designed the review, coordinated and supervised analysis, critically reviewed and revised the manuscript and approved the final manuscript as submitted. All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: There is no additional unpublished data from this study, as it is a systematic literature review. Any additional information is contained within the submitted appendices.

References

- 1. Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. New York: United Nations General Assembly, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wiens MO, Kissoon N, Kabakyenga J. Smart discharges to address a neglected epidemic in sepsis. JAMA pediatrics 2018;172:213–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Reinhart K, Daniels R, Kissoon N, et al. Recognizing sepsis as a global health priority - a WHO resolution. N Engl J Med 2017;377:414–7. 10.1056/NEJMp1707170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kissoon N, Reinhart K, Daniels R, et al. Sepsis in children: global implications of the World Health Assembly Resolution on Sepsis. Pediatr Crit Care Med 2017;18:e625–7. 10.1097/PCC.0000000000001340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wiens MO, Pawluk S, Kissoon N, et al. Pediatric post-discharge mortality in resource poor countries: a systematic review. PLoS One 2013;8:e66698 10.1371/journal.pone.0066698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jahan S. Overview: human development report 2016: human development for everyone. New York, NY: United Nations Development Programme, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Klugman J. Human development report 2011. New York: United Nations Development Program, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Veirum JE, Sodeman M, Biai S, et al. Increased mortality in the year following discharge from a paediatric ward in Bissau, Guinea-Bissau. Acta Paediatr 2007;96:1832–8. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00562.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Moïsi JC, Gatakaa H, Berkley JA, et al. Excess child mortality after discharge from hospital in Kilifi, Kenya: a retrospective cohort analysis. Bull World Health Organ 2011;89:725–32. 10.2471/BLT.11.089235 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wiens MO, Kumbakumba E, Larson CP, et al. Postdischarge mortality in children with acute infectious diseases: derivation of postdischarge mortality prediction models. BMJ Open 2015;5:e009449 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wiens MO. Childhood mortality from acute infectious diseases in Uganda: Studies in sepsis and post-discharge mortality: University of British Columbia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kerac M, Bunn J, Chagaluka G, et al. Follow-up of post-discharge growth and mortality after treatment for severe acute malnutrition (FuSAM study): a prospective cohort study. PLoS One 2014;9:1–10. 10.1371/journal.pone.0096030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chisti MJ, Graham SM, Duke T, et al. Post-discharge mortality in children with severe malnutrition and pneumonia in Bangladesh. PLoS One 2014;9:e107663 10.1371/journal.pone.0107663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hennart P, Beghin D, Bossuyt M. Long-term follow-up of severe protein-energy malnutrition in Eastern Zaïre. J Trop Pediatr 1987;33:10–12. 10.1093/tropej/33.1.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Berkley JA, Ngari M, Thitiri J, et al. Daily co-trimoxazole prophylaxis to prevent mortality in children with complicated severe acute malnutrition: a multicentre, double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health 2016;4:e464–73. 10.1016/S2214-109X(16)30096-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Chhibber AV, Hill PC, Jafali J, et al. Child mortality after discharge from a health facility following suspected pneumonia, meningitis or septicaemia in rural gambia: a cohort study. PLoS One 2015;10:e0137095 10.1371/journal.pone.0137095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Villamor E, Misegades L, Fataki MR, et al. Child mortality in relation to HIV infection, nutritional status, and socio-economic background. Int J Epidemiol 2005;34:61–8. 10.1093/ije/dyh378 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ngari MM, Fegan G, Mwangome MK, et al. Mortality after inpatient treatment for severe pneumonia in children: a cohort study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 2017;31:233–42. 10.1111/ppe.12348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Roy SK, Chowdhury AK, Rahaman MM. Excess mortality among children discharged from hospital after treatment for diarrhoea in rural Bangladesh. Br Med J 1983;287:1097–9. 10.1136/bmj.287.6399.1097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Islam MA, Rahman MM, Mahalanabis D, et al. Death in a diarrhoeal cohort of infants and young children soon after discharge from hospital: risk factors and causes by verbal autopsy. J Trop Pediatr 1996;42:342–7. 10.1093/tropej/42.6.342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Biai S, Rodrigues A, Gomes M, et al. Reduced in-hospital mortality after improved management of children under 5 years admitted to hospital with malaria: randomised trial. BMJ 2007;335:862 10.1136/bmj.39345.467813.80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Opoka RO, Hamre KES, Brand N, et al. High postdischarge morbidity in ugandan children with severe malarial anemia or cerebral malaria. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc 2016. 64:piw060 10.1093/jpids/piw060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Phiri K, Esan M, van Hensbroek MB, et al. Intermittent preventive therapy for malaria with monthly artemether-lumefantrine for the post-discharge management of severe anaemia in children aged 4-59 months in southern Malawi: a multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis 2012;12:191–200. 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70320-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Zucker JR, Lackritz EM, Ruebush TK, et al. Childhood mortality during and after hospitalization in western Kenya: effect of malaria treatment regimens. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1996;55:655–60. 10.4269/ajtmh.1996.55.655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Phiri KS, Calis JC, Faragher B, et al. Long term outcome of severe anaemia in Malawian children. PLoS One 2008;3:e2903 10.1371/journal.pone.0002903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Olupot-Olupot P, Engoru C, Thompson J, et al. Phase II trial of standard versus increased transfusion volume in Ugandan children with acute severe anemia. BMC Med 2014;12:67 10.1186/1741-7015-12-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. English L, Kumbakumba E, Larson CP, et al. Pediatric out-of-hospital deaths following hospital discharge: a mixed-methods study. Afr Health Sci 2016;16:883–91. 10.4314/ahs.v16i4.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kissoon N, Carapetis J. Pediatric sepsis in the developing world. J Infect 2015;71:S21–6. 10.1016/j.jinf.2015.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Dugani S, Laxminarayan R, Kissoon N. The quadruple burden of sepsis. CMAJ 2017;189:E1128–29. 10.1503/cmaj.171008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wiens MO, Kumbakumba E, Larson CP, et al. Scheduled follow-up referrals and simple prevention kits including counseling to improve post-discharge outcomes among children in uganda: a proof-of-concept study. Glob Health Sci Pract 2016;4:422–34. 10.9745/GHSP-D-16-00069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. The Childhood Acute Illness & Nutrition Network. 2017. http://www.chainnetwork.org/about-us/

- 32. Grenov B, Namusoke H, Lanyero B, et al. Effect of probiotics on diarrhea in children with severe acute malnutrition: a randomized controlled study in Uganda. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2017;64:396–403. 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001515 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. West TE, Goetghebuer T, Milligan P, et al. Long-term morbidity and mortality following hypoxaemic lower respiratory tract infection in Gambian children. Bull World Health Organ 1999;77:144–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ashraf H, Alam NH, Chisti MJ, et al. Observational follow-up study following two cohorts of children with severe pneumonia after discharge from day care clinic/hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000961 10.1136/bmjopen-2012-000961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reddy EA, Njau BN, Morpeth SC, et al. A randomized controlled trial of standard versus intensified tuberculosis diagnostics on treatment decisions by physicians in Northern Tanzania. BMC Infect Dis 2014;14:89 10.1186/1471-2334-14-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Newberry L, O’Hare B, Kennedy N, et al. Early use of corticosteroids in infants with a clinical diagnosis of Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in Malawi: a double-blind, randomised clinical trial. Paediatr Int Child Health 2017;37:121–8. 10.1080/20469047.2016.1260891 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stanton B, Clemens J, Khair T, et al. Follow-up of children discharged from hospital after treatment for diarrhoea in urban Bangladesh. Trop Geogr Med 1986;38:113–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-023445supp001.pdf (183KB, pdf)