Abstract

Objectives

Fly-in, fly-out (FIFO) work involves long commutes, living on-site for consecutive days and returning home between shifts. This unique type of work requires constant transitioning between the roles and routines of on-shift versus off-shift days. This study aims to examine health behaviour patterns of FIFO workers and FIFO partners during on-shift and off-shift time frames.

Design

This study used ecological momentary assessment and multilevel modelling to examine daily health behaviours.

Setting

FIFO workers and FIFO partners from across Australia responded to daily online surveys for up to 7 days of on-shift and up to 7 days of off-shift time frames.

Participants

Participants included 64 FIFO workers and 42 FIFO worker partners.

Results

Workers and partners reported poorer sleep and nutrition quality for on-shift compared with off-shift days. Both workers and partners exercised less, smoked more cigarettes, took more physical health medication and drank less alcohol during on-shift compared with off-shift days.

Conclusions

FIFO organisations should consider infrastructure changes and support services to enhance opportunities for quality sleep and nutrition, sufficient exercise, moderate alcohol consumption and cigarette cessation for workers on-site and their partners at home.

Keywords: long-distance commuting, exercise, sleep, smoking, alcohol

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to our knowledge to have explored the impact of long-distance commuting on the health behaviours of both fly-in, fly-out (FIFO) workers and FIFO partners.

Participants were recruited from across Australia, including those at FIFO sites.

Health behaviours were reported during both on-shift and off-shift times.

Self-report measures used to minimise potential burden on participants have meant responses are based on participant perception of their health behaviours.

Introduction

Fly-in, fly-out (FIFO) work is a form of long-distance commuting in which workers travel long distances to live on-site during their work shifts (typically 12-hour days for 7–24 consecutive days), then travel home for their off-shift days.1 2 Most prominent amidst mining, construction and resource sectors, FIFO work has become customary in some regional Australian areas, in which as many as 17% of people are FIFO workers.1 3 Calls for studies of the health effects of the FIFO lifestyle on workers and their families to help inform a comprehensive health policy4 have largely been unanswered. Understanding the typical health-related behaviours among workers and their partners will likely aid efforts to design such policy. Previous research indicates that, for both FIFO workers and their partners, on-shift and off-shift periods are characterized by different day-to-day routines.5 The aim of this study was to investigate differences in health behaviours of FIFO workers and partners of FIFO workers during on-shift and off-shift days.

Compared with people with other types of employment, FIFO workers are more likely to smoke, drink excessive amounts of alcohol, and be overweight or obese.6 7 Qualitative studies of FIFO mining communities have provided insight into the everyday experiences that may contribute to these health-related associations. For example, while on-site recreational facilitates can make exercise on-shift accessible and appealing,8 some workers report that exercise opportunities are limited by long work hours and a lack of opportunity for regular participation in team sports or recreation programmes.9 There is a prevalent drinking culture on FIFO mining sites, with social pressure to consume alcohol.9 FIFO mining workers also report regularly feeling tired and fatigued, which may hint at disturbances in sleep quality while on-shift.9 This research indicates that FIFO workers engage in less healthy behaviours than people in other types of employment; however, the available research provides little insight into how health behaviours fluctuate across this unique lifestyle or into the health behaviours of partners of FIFO workers.

The distinct contexts and routines that characterise on-shift and off-shift periods for both the FIFO worker and their partners5 must be considered when monitoring health behaviours. Ecological momentary assessment (EMA) is the observation of individuals’ recent states or behaviours through multiple assessments over time in real-world environments.10 11 EMA has been instrumental in understanding health behaviours in non-FIFO populations (eg,12–14). For example, Carney et al 12 applied EMA to investigate links between social behaviours and sleep quality, revealing that poor sleep quality was linked to lower regularity and frequency of social interactions.

EMA may also provide important insight into FIFO life. For example, in one study, FIFO workers completed diary-style surveys every 3 days of their on-shift work roster about their experiences and perceived support on the job.15 Engagement and supervisor support declined over the course of FIFO on-shifts, and daily workload and emotional demands predicted daily emotional exhaustion. Another study which objectively monitored sleep found that FIFO mining workers slept, on average, an hour longer during off-shift (7.0±1.9) compared with on-shift periods (6.0±1.0).16 Beyond this sleep monitoring study, there is little evidence of other health behaviours across time for FIFO workers and no evidence tracking health behaviours of partners of FIFO workers. There have been calls to aid FIFO workers and families in adapting to the unique lifestyles that these work shifts elicit.4 Understanding the existing health behaviours of this population is an important prerequisite to such interventions. Past qualitative and cross-sectional studies have suggested that FIFO shifts may impact sleep and nutrition quality, time spent exercising and relaxing, smoking and alcohol consumption, and medication use.6–9 16 Yet, little attention has been paid to on-shift and off-shift differences in these behaviours, and little is known about engagement in these behaviours among partners of FIFO workers. The aim of this study is to compare health behaviours between on-shift and off-shift periods, between FIFO workers and their partners, and between FIFO workers and their partners on on-shift versus off-shift periods. Specifically, we compare health behaviours for all participants between on-shift and off-shift days, between FIFO workers and partners on all days, and whether differences between workers and partners are magnified on on-shift or off-shift days.

Method

Participant involvement

Participants were not involved in the design of this study. However, participants were encouraged to invite fellow FIFO workers and/or partners to join the study. It is unclear how many of our participants were referred in this manner. Participants who indicated interest during the survey will receive an overview summary of the study’s findings as well as a link to published manuscripts for further reading.

Participants and procedures

This study was part of the FIFO Lifestyle EMA study in which FIFO workers (n=64) and partners of FIFO workers (n=42) completed daily diaries of their health behaviours and well-being for up to 7 consecutive on-shift and 7 consecutive off-shift days. Participants were recruited through social media forums and posts (eg, posts on FIFO-related social media group pages), as well as traditional media outlets (eg, newspaper, television coverage). An initial survey was used to assess participants’ sex, age, post code, occupation, household income, height (cm) and weight (kg). Diaries were scheduled to start mid-way throughout the on-shift and off-shift period to ensure that behaviours were typical of on-shift and off-shift periods, rather than capturing behavioural reactivity to the transition from on-shift to off-shift or vice versa. Participants were emailed links to secure web surveys at 16:00 each day with instructions to complete the online-based diaries at the end of the same day. Most participants (n=68; 64%) were not in relationships with other study participants; 19 couples (ie, 19 workers (30% of all workers), 19 partners (45% of all partners)) participated in the study.

Measures

Each day, participants were asked to self-report their daily health behaviours in reference to ‘today’. Single-item measures can be sensitive to change across time and between groups and were used to reduce participant burden due to multiple assessments.10

Sleep quality was assessed with the item, “Do you feel like you had enough sleep last night?” with response options that ranged from −2 (No, not at all) to 0 (Indifferent) to +2 (Yes, definitely). Nutrition quality was assessed with the item, “Do you feel you had adequate nutritional food today?” with the same response options. Exercise time (“How much exercise did you do today?”) was reported in hours and minutes, and transformed to minutes for the analyses. Relaxation time (“How many hours of quiet relaxation did you do today?”) was reported in hours. Participants reported how many alcoholic drinks they had and how many cigarettes they smoked “today” using an open response box, and reported whether they took any “prescribed medication for mental impairments (eg, depression, anxiety) today” and “prescribed medication for physical impairments (eg, blood pressure, headaches, respiratory disorders) today” using Yes/No options.

Data management and analysis

Intraclass correlations (ICCs)17 with 95% CIs were calculated to quantify the variability uniquely attributable to the between-person level. ICCs are proportions (possible range 0 to 1) with larger values indicative of more stability (ie, lower change across time). Multilevel models account for nested data and provide robust estimates of between-person and within-person effects.18 Data were nested within-person (across time) as well as between partners for those19 couples in which both partners were in the study; therefore, three-level multilevel models were specified to estimate the differences between workers and partners and between work and home days. The first set of models tested the effects of day (on-shift vs off-shift) and status (worker vs partner) on the outcome. The second set tested the interactive effects of time by status, to establish whether the differences between worker versus partner varied between on-shift and off-shift days. All models were linear, except for those with dichotomous medication outcomes (no, yes), which were logistic. Only those participants who reported smoking at least one cigarette throughout the study (n=96 days from 19 individuals) were included in the model predicting cigarettes smoked. No variability was explained at the partner level for the first model predicting medication use for mental health nor for either model predicting cigarettes smoked, so these were estimated as two-level models. Ninety-five per cent CIs were estimated from 1000 bootstrap simulations.19 All analyses were conducted in R V.3.1.3.20

Results

Participants were 64 FIFO workers (age: M 40.39, SD 10.34; 51 men, 13 women; Body Mass Index (BMI): M 28.86, SD 5.01) and 42 partners of FIFO workers (age: M 38.58, SD 9.22; 40 women (two no response); BMI: M 27.65, SD 7.59). The most commonly reported occupations were managers/professionals (n=30, 28.3%), tradespersons/labourers (n=23, 21.7%), production/transport (n=19, 17.9%) and clerical/sales/service (n=13, 12.3%). Household incomes were between $A47 500 and $A350 000 (~US$37 600–US$277 000), with mean earnings $A190 000±$A68 000 (~US$150 500±US$54 000). Participants were mostly from Queensland (n=61, 57.5%) and Western Australia (n=24, 22.6%), with others from South Australia (n=6), Tasmania (n=1), Victoria (n=7) and New South Wales (n=5). On average, participants completed 7.46 (SD 4.89) days of data, with 3.22 (SD 2.96) on-shift and 4.21 (SD 3.84) off-shift days reported.

Person-level descriptive statistics for health behaviours are shown in table 1 (column 2). On average, participants reported modest sleep and nutrition quality (M 0.04 and 0.35, respectively, on −2 to +2 scales). Participants reported getting about 45 min of exercise, nearly 3 hours of relaxation time and consuming one alcoholic drink per day, on average. Use of prescribed medications for physical or mental health was rare. Of those who smoked (n=19), the daily average was 13 cigarettes. ICCs and CIs are also shown in table 1 (column 3). Exercise time varied the most day-to-day (ie, was least stable), with only 18% of the variability resulting from between-person differences. Alcohol consumption and sleep and nutrition quality were modestly stable, in that more than half of the variability was attributable to within-person variation. Number of cigarettes smoked and medication use for mental and physical health were very stable, with 92%, 93% and 78% of the variability attributable to between-person differences, respectively.

Table 1.

Person-level descriptive statistics, intraclass correlations (ICCs) and estimates of multilevel models testing differences in health behaviour of fly-in, fly-out workers and their partners for on-shift and off-shift days

| Descriptive statistics | Intraclass correlations | Partners vs workers | On-shift vs off-shift days | Status×day interaction | |

| Model 1 | Model 2 | ||||

| M (SD)* | ICC (95% CI) | γ, 95% CI | γ, 95% CI | γ, 95% CI | |

| Sleep quality | 0.04 (1.04) | 0.33 (0.24 to 0.43) | −0.20 (−0.51 to 0.10) | −0.56 (−0.72 to −0.40) | 0.56 (0.14 to 0.94) |

| Nutrition quality | 0.35 (1.01) | 0.47 (0.38 to 0.57) | −0.17 (−0.50 to 0.15) | −0.17 (−0.33 to −0.02) | 0.26 (−0.10 to 0.60) |

| Exercise time (min/day) | 43.80 (58.81) | 0.18 (0.09 to 0.29) | −10.96 (−0.48 to 0.11) | −10.78 (−0.36 to −0.00) | 3.65 (−16.27 to 26.88) |

| Relaxation time (hours/day) | 2.78 (4.35) | 0.31 (0.22 to 0.42) | −0.65 (−1.87 to 0.69) | −1.22 (−1.87 to −0.61) | 0.80 (−0.75 to 2.39) |

| Alcohol drinks (#/day) | 1.05 (1.69) | 0.29 (0.20 to 0.39) | −0.91 (−1.50 to −0.26) | −1.12 (−1.48 to −0.76) | 1.16 (0.32 to 2.00) |

| Cigarettes (#/day)† | 13.22 (8.46) | 0.92 (0.89 to 0.94) | 4.86 (−7.88 to 16.69) | 24.20 (0.86 to 45.88) | −15.79 (−30.00 to −0.57) |

| Mental health medication (#/day)‡ | 0.08 (0.27) | 0.93 (0.91 to 0.95) | 0.09 (−36.03 to 38.87) | 1.65 (−1.24 to 4.26) | −11.33 (−51.81 to 28.10) |

| Physical health medication (#/day)‡ | 0.16 (0.34) | 0.78 (0.72 to 0.83) | 0.39 (−8.40 to 8.14) | 1.44 (0.36 to 2.54) | −0.52 (−2.86 to 1.93) |

*Descriptive statistics calculated for person-level averages across days.

†Used subsample of 68 days from 19 individuals who smoked.

‡Logistic models.

Bold text indicates estimates are statistically significantly different from zero.

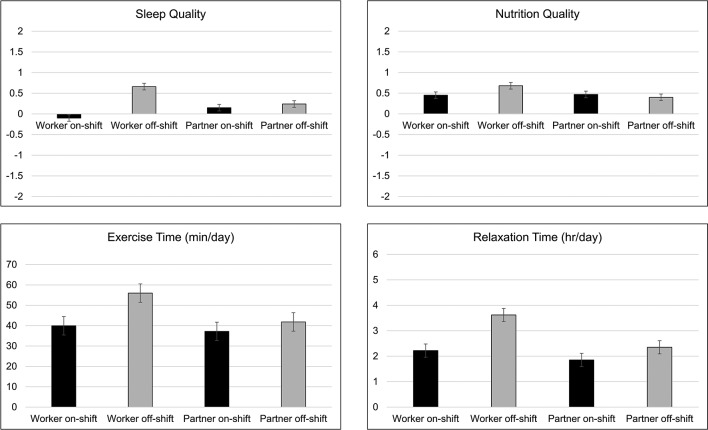

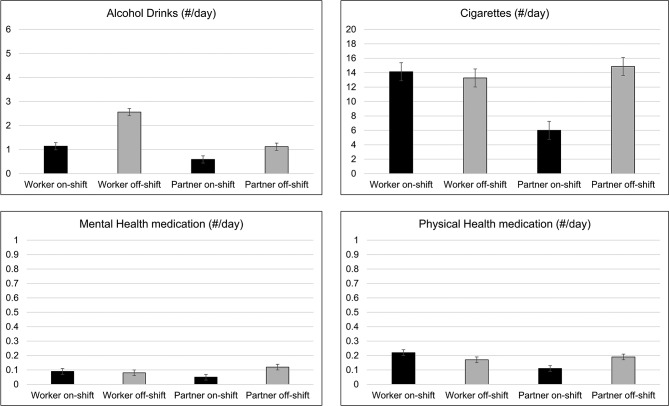

Plots of the health behaviours are shown in figures 1 and 2. The results of the multilevel models are also shown in table 1 (columns 4–6). Sleep quality was significantly worse during on-shift compared with off-shift and this effect tended to be magnified for workers, but there was no overall difference between workers’ and partners’ sleep quality. Both workers and partners tended to have poorer nutrition quality, less exercise time and less relaxation time during on-shift days than off-shift days, but there were no differences in these health behaviours between workers and partners. Partners drank significantly less alcohol than workers and both tended to drink more alcohol during off-shift versus on-shift days, with this effect larger for workers than partners. Among smokers, both workers and partners tended to smoke more during on-shift versus off-shift days, and the difference was more magnified among partners. There were no differences between workers and partners, or between on-shift and off-shift days in mental health medication use; however, overall partners and workers reported taking more physical health medication during on-shift days than off-shift days.

Figure 1.

Plots of the average daily sleep quality, nutrition quality, exercise time and relaxation time of fly-in, fly-out workers and partners of on-shift days and off-shift days.

Figure 2.

Plots of the average daily alcohol drinks, cigarettes and medication for mental and physical health of fly-in, fly-out workers and partners of on-shift days and off-shift days.

Discussion

This study revealed important differences in daily health behaviour within and between FIFO workers and partners across on-shift and off-shift days. Previous studies have investigated daily health behaviours in the general population (eg,12–14), but this is the first EMA study comparing health behaviours of FIFO workers and their partners during on-shift and off-shift days. Similar to past studies of other populations (eg,12–14), exercise time, sleep quality, nutrition quality and alcohol consumption varied considerably day-to-day. Variability in health behaviours highlights the need to account for contextual and person factors when monitoring or intervening with these health behaviours among this population. Whether it is an on-shift or off-shift day appears to be an important contextual factor for health behaviours of FIFO workers and their partners.

Sleep quality was poorer and less time was available for relaxing during on-shift compared with off-shift days. This aligns with objective monitoring of FIFO mining workers’ sleep16 and qualitative evidence that FIFO workers experience excessive fatigue and tiredness.9 The 12-hour work shifts common to FIFO work lead to fatigue, which is detrimental to performance.21 Fatigue can impair performance to levels equivalent to alcohol intoxication22 and puts workers at higher accident and injury risk.23 24 Reducing fatigue and its associated health and safety risks will require investment from both FIFO workplaces and workers. FIFO workplaces might fruitfully seek to provide sufficient sleep opportunities and environments and encourage workers to use these opportunities.25 Importantly, our findings are the first to show that these effects of FIFO shift on health behaviours also impact workers’ partners and highlight the need for further investigation into the health impacts of FIFO work on workers’ families.

Both FIFO workers and partners reported exercising less during on-shift compared with off-shift periods. It may be that people have less time to fit exercise into their schedules during on-shift days (either because of work or additional home responsibilities while partner is on-site) (but see Rebar et al 26). On average, both workers and partners reported exercising for more than 30 min per day, although this has highly variable day-to-day. These findings are contrary to Australian national survey data that people in blue collar occupations were 50% more likely to be classified as inactive, compared with white collar or professional jobs.27 Nonetheless, FIFO workers may benefit from having access to on-site recreational facilities (eg, gymnasiums, sports courts). Previous research showed that FIFO mining workers with access to such facilities enjoyed the opportunities to exercise and felt a stronger sense of community.8 Using such facilities may also promote displacement of prevalent unhealthy on-site behaviours, such as excessive alcohol consumption.9

FIFO workers and partners also reported poorer nutrition quality during on-shift compared with off-shift periods. Providing workers with healthy meal options may help reduce fatigue and improve mood during shifts,28 although our finding that the effect of shift on nutrition quality was present for both workers and partners suggests the problem is not entirely the result of on-site availability of healthy choices. It may be that healthy choices are less prioritised when partners are separated, either as a result of the reduced impact on one another’s eating choices or less available time and more stress being present when apart.

We found that FIFO workers consumed more alcohol, on average, than partners. This echoes past between-person comparison research suggesting that FIFO mining workers tended to drink more alcohol than people with other employment.6 7 However, most FIFO workers in our study were men and FIFO partners were women. Our results may simply reflect the well-documented gender effect where women typically drink less alcohol than men.29 FIFO workers and partners reported consuming more alcohol when off-shift, an effect magnified for workers. This finding is surprising given that past research suggests social life during FIFO work on-shifts is perceived to centre on alcohol consumption.9 Our findings may indicate that social and environmental facilitators of alcohol consumption are present both on-site and off-site for FIFO workers, and within domestic contexts for partners. As such, interventions should not exclusively concentrate on FIFO sites, but rather consider the personal, social and environmental factors associated with risky alcohol consumption in both work and home contexts.

Our data also revealed that both FIFO workers and partners smoked more cigarettes when on-shift with the effect of shift magnified for partners, though analyses were based on only 19 smokers, so were likely underpowered to detect true between-person differences. Previous EMA studies suggest that adults smoke more on days on which they experience high stress.30 It may be that the added stressors of work days elicit more urges to smoke cigarettes for both workers, and the partners of absent workers. Given the multitude of negative health consequences attributable to smoking cigarettes,31 smoking cessation interventions for FIFO workers might usefully incorporate advice on stress management.32

This study has limitations that must be acknowledged. Most participants were from Queensland or Western Australia, where most mining sites are located.1 3 Results may not be generalisable beyond this targeted population. Additionally, our aim was to address several daily health behaviours, so single items were used to assess the behaviours while minimising participant burden. Although effective for showing change across time,10 the use of single items precludes assessment of the reliability and validity of self-reported behaviour data, which in turn potentially questions the validity of population-level comparisons. Additionally, the measures were reliant on participants’ perceptions of the adequacy of health behaviours (eg, ‘enough sleep’, ‘adequate nutritional food’) and may not reflect recommended levels of the health behaviours. Future research with objective or more comprehensive self-report measures is necessary to more rigorously determine true levels of FIFO workers’ and partners’ health behaviours.

Additionally, while we have focused on engagement in health behaviours, future research might consider other elements of the FIFO work context that affect health, either directly, or via influence on health behaviours. For example, shift type (night vs day) and roster length may be important factors in determining the level of daily job demands and stressors, which in turn may influence engagement in health behaviour, and health outcomes (but see Paech et al 16). Availability of health-supportive infrastructure is also likely to influence health and was not assessed in our study: access to recreational facilities including gymnasiums, sports courts and healthy food options facilitate health behaviours, whereas accessible pubs and unhealthy food options permit unhealthy behaviours while on-site.8 Additionally, our study contained only a small subgroup of data for both partners in a relationship, so dyadic modelling and actor–partner effects were not able to be tested. The dynamic impact that partners have on each other’s health behaviours will be important to consider in future research on FIFO populations. Notwithstanding these limitations, our study is the first to our knowledge to assess variation in health behaviours over time, and to examine both workers and their partners.

Conclusions

This study showed FIFO workers had poorer sleep quality when on-shift, and both workers and partners exercised less and smoked more on on-shift days, and drank more alcohol on off-shift than on-shift days. Given that the FIFO lifestyle leads to disruptions across a multitude of health behaviours, FIFO workplaces may consider supporting multiple health behaviour change interventions.33

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Obtained.

Contributors: K-LA, CV, BG and ALR helped conceive of the idea of the study design, collected the data and provided intellectual content for the manuscript. ALR conducted the data analysis, assisted in interpreting the findings and provided intellectual content for the manuscript. All authors were involved in drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content, and gave approval of the final version to be published.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: The not-for-profit organisation LIVIN Australia donated incentives for participants in the study, but had no influence on the study procedures, data collection, analyses or dissemination. ALR receives funding from the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia. CV receives funding from the National Heart Foundation of Australia.

Ethics approval: All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. All study procedures were approved a priori by the Central Queensland University’s Human Research Ethics Committee, approval number H16/09-269.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Extra data are available by emailing the corresponding author (ALR).

References

- 1. Australian Bureau of Statistics. Fly-in Fly-out (FIFO) Workers (No. 6105.0). Canberra, Australia: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2. De Silva H, Johnson L, Wade K. Long distance commuters in Australia: a socio-economic and demographic profile Staff Papers, Paper given to the 34th Australasian Transport Research Forum, 2011:28–30. Retrieved from http://atrf.info/papers/2011/2011_desilva_johnson_wade.pdf

- 3. Education and Health Standing Committee. The impact of FIFO work practices on mental health (No. 5). Perth, WA, Australia: Legislative Assembly, Parliament of Western Australia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. House of Representatives Standing Committee on Regional Australia. Cancer of the bush or salvation for our cities?: Fly-in, fly-out and drive-in, drive-out workforce practices in regional Australia. Canberra, Australia: Commonwealth of Australia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Gardner B, Alfrey KL, Vandelanotte C, et al. Mental health and well-being concerns of fly-in fly-out workers and their partners in Australia: a qualitative study. BMJ Open 2018;8:e019516 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-019516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Joyce SJ, Tomlin SM, Somerford PJ, et al. Health behaviours and outcomes associated with fly-in fly-out and shift workers in Western Australia. Intern Med J 2013;43:440–4. 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2012.02885.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tynan RJ, Considine R, Wiggers J, et al. Alcohol consumption in the Australian coal mining industry. Occup Environ Med 2017;74:259–67. 10.1136/oemed-2016-103602 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Perring A, Pham K, Snow S, et al. Investigation into the effect of infrastructure on fly-in fly-out mining workers. Aust J Rural Health 2014;22:323–7. 10.1111/ajr.12117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Torkington AM, Larkins S, Gupta TS. The psychosocial impacts of fly-in fly-out and drive-in drive-out mining on mining employees: a qualitative study. Aust J Rural Health 2011;19:135–41. 10.1111/j.1440-1584.2011.01205.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Stone AA, Shiffman S. Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) in behavioral medicine. Ann Behav Med 1994;16:199–202. 10.1093/abm/16.3.199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Trull TJ, Ebner-Priemer UW. Using experience sampling methods/ecological momentary assessment (ESM/EMA) in clinical assessment and clinical research: introduction to the special section. Psychol Assess 2009;21:457–62. 10.1037/a0017653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Carney CE, Edinger JD, Meyer B, et al. Daily activities and sleep quality in college students. Chronobiol Int 2006;23:623–37. 10.1080/07420520600650695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Hyde AL, Conroy DE, Pincus AL, et al. Unpacking the feel-good effect of free-time physical activity: between- and within-person associations with pleasant-activated feeling states. J Sport Exerc Psychol 2011;33:884–902. 10.1123/jsep.33.6.884 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. O’Connor DB, Jones F, Conner M, et al. Effects of daily hassles and eating style on eating behavior. Health Psychol 2008;27:S20–31. 10.1037/0278-6133.27.1.S20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Albrecht SL, Anglim J. Employee engagement and emotional exhaustion of fly-in-fly-out workers: a diary study. Australian Journal of Psychology 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Paech GM, Jay SM, Lamond N, et al. The effects of different roster schedules on sleep in miners. Appl Ergon 2010;41:600–6. 10.1016/j.apergo.2009.12.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wolak ME, Fairbairn DJ, Paulsen YR. Guidelines for estimating repeatability. Methods Ecol Evol 2012;3:129–37. 10.1111/j.2041-210X.2011.00125.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bates DM. lme4: Linear mixed-effects models using Eigen and S4 (Version R Package version 1.1-7). 2014. Retrieved from http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=lme4

- 19. Gelman A. arm: Data Analysis Using Regression and Multilevel/Hierarchical Models (Version 1.8-4.). 2015. Retrieved from http://CRAN.R-project.org/package=arm

- 20. Core Team R. R: a language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.R-project.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ferguson SA, Paech GM, Dorrian J, et al. Performance on a simple response time task: is sleep or work more important for miners? Appl Ergon 2011;42:210–3. 10.1016/j.apergo.2010.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lamond N, Dawson D. Quantifying the performance impairment associated with fatigue. J Sleep Res 1999;8:255–62. 10.1046/j.1365-2869.1999.00167.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dinges DF. An overview of sleepiness and accidents. J Sleep Res 1995;4(S2):4–14. 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1995.tb00220.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Folkard S, Lombardi DA. Modeling the impact of the components of long work hours on injuries and "accidents". Am J Ind Med 2006;49:953–63. 10.1002/ajim.20307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Dawson D, McCulloch K. Managing fatigue: it’s about sleep. Sleep Med Rev 2005;9:365–80. 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rebar AL, Johnston R, Paterson JL, et al. A test of how Australian adults allocate time for physical activity. Behav Med 2017:1–6. 10.1080/08964289.2017.1361902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Burton NW, Turrell G. Occupation, hours worked, and leisure-time physical activity. Prev Med 2000;31:673–81. 10.1006/pmed.2000.0763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Leedo E, Beck AM, Astrup A, et al. The effectiveness of healthy meals at work on reaction time, mood and dietary intake: a randomised cross-over study in daytime and shift workers at an university hospital. Br J Nutr 2017;118:121–9. 10.1017/S000711451700191X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wilsnack RW, Vogeltanz ND, Wilsnack SC, et al. Gender differences in alcohol consumption and adverse drinking consequences: cross-cultural patterns. Addiction 2000;95:251–65. 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2000.95225112.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Todd M. Daily processes in stress and smoking: effects of negative events, nicotine dependence, and gender. Psychol Addict Behav 2004;18:31–9. 10.1037/0893-164X.18.1.31 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Health UDof, Services H, et al. The health consequences of smoking: a report of the Surgeon General. 2004. Retrieved from http://www.therapy-store.com/smoking/women__tobacco.htm

- 32. Moher M, Hey K, Lancaster T. Workplace interventions for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005:CD003440 10.1002/14651858.CD003440.pub2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Prochaska JJ, Spring B, Nigg CR. Multiple health behavior change research: an introduction and overview. Prev Med 2008;46:181–8. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.02.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.