Abstract

Introduction

eHealth is critically important to build strong health systems, and accelerate the achievement of sustainable development goals, particularly universal health coverage. To support and strengthen the health system, the eHealth architecture needs to be formulated and established prior to the implementation and development of any national eHealth applications and services. The aim of this study is to design and validate a standard questionnaire to assess the current status of national eHealth architecture (NEHA) components.

Methods and analysis

This study will use a mixed-methods design consisting of four phases: (1) item generation through review of evidences and experts’ opinions, (2) face and content validity of the questionnaire, (3) determination of a range of possible scenarios for each item included in the questionnaire and (4) evaluation of reliability. This questionnaire is expected to generate critical and important information about the status of NEHA components that will be useful for monitoring, formulating, developing, implementing and evaluating NEHA. Our paper will contribute, we envisage, to establishment of a socio-technical basis on which governments and other relevant sectors can compare the policy interventions that boost the availability and utilisation of eHealth services within their settings.

Ethics and dissemination

The Ethics Committee for Research at the Tehran University of Medical Sciences approved the study protocol. We will obtain informed consent from each participant and collect data anonymously to maintain confidentiality. The translation of the findings into future policy planning will include the production of a series of peer-reviewed articles, presentation of the findings at relevant eHealth conferences and preparation of policy reports to the international organisations aiming to strengthen national capacity for better-informed eHealth architecture.

Keywords: health informatics, information technology, health policy, information management

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study will propose, following a robust and mixed-method design, a validated instrument with focus on the national eHealth architecture (NEHA).

The findings will advance the existing knowledge about the status of NEHA components in different countries, which can create an evidence-based platform to learn from both achievements and mistakes for improving practices.

The latter will help develop eHealth architecture prior to the implementation, scale up and development of any national eHealth solution, which can help improve the efficiency of health systems.

The number of items are relatively high in the questionnaire, which may compromise participants’ compliance.

Although the questionnaire is comprehensive and applicable to all settings, it might overlook some contextual factors that might affect the process across different settings.

Introduction

Health systems have great opportunities to alleviate the healthcare resource constraints and reduce costs. These can be realised through investment in technology to help better healthcare coordination and move all functions of public health management into the service economy.1 As an umbrella concept, eHealth is defined as the combined use of information and communication technologies (ICT) in the health sector for clinical, educational and administrative purposes. The eHealth solutions, eg, telehealth, mobile health, electronic health records, electronic prescription, are considered as cost-effective applications for improving equity in access and patient safety, enhancing quality of healthcare delivery, implementing change management in healthcare organisations and promoting the exchange of information and quality of health data.2–13 eHealth also plays a critical role in building the foundation for a robust health system towards universal health coverage, which builds the fundamental component of sustainable health development.14 eHealth technologies and their successful implementation in the health systems have been well known for a long time.15

The enhanced insight about eHealth has led the policy makers in many countries to expand their investment in various eHealth products.16 Like other settings, eHealth has become fundamental in managing the limited available resources to achieve more health for money and better quality of care in low and middle-income countries (LMICs).17 Nevertheless, due to poor infrastructure, limited resources and lack of political commitment and support, the implementation of ICT has been challenging in the LMICs.18 Concerns and expectations from eHealth in high-income countries differ from the LMICs.19 Hence, the LMICs can benefit from transferable lessons for investing and adopting the eHealth solutions. This is a crucial step for successful transformation of healthcare systems in the LMICs.20

Being aware of various descriptions of the concept, we define eHealth architecture as structure of eHealth components, their functions and inter-relationships, as well as the principles and guidelines that govern their design and evolution over time.21 Before any attempt for production, implementation and scaling-up eHealth solutions, healthcare systems require the development of a national eHealth architecture (NEHA) based on a clear understanding of their needs and expectations. This may pave the way to accommodate the appropriate information and technology solutions that are tailored to countries’ needs.22 23 An evidence-informed NEHA is the backbone of eHealth system to design and implement eHealth solutions.

Our experience suggests that many countries have been implementing eHealth solutions into their healthcare settings. However, in advance development of a tailored22 24 eHealth architecture at the national level has not taken place in many countries. To promote successful adoption of national eHealth policies, it is crucial to assess the current status of NEHA. This study is motivated since hitherto there is no validated instrument with a focus on the NEHA components. Our research aims to bridge this gap through designing and validating a questionnaire to understand NEHA. Through first painting a clearer picture of the existing situation, and second creating a platform to compare the status of eHealth architecture across various settings, our findings can contribute to, we hope, improve the increasing initiatives in adopting meaningful eHealth solutions anywhere.

Methods

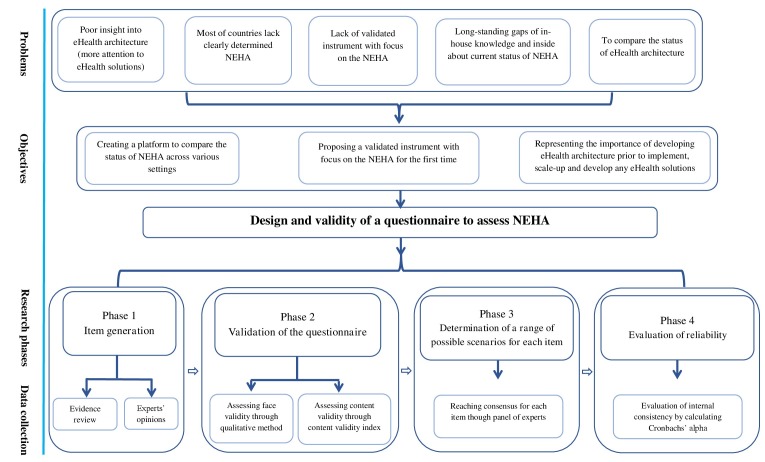

This study will employ a mixed-methods design to construct and validate a questionnaire on the status of NEHA. Our work will have four sequential phases: (1) item generation through review of the evidences and experts’ opinions, (2) evaluating the face and content validity of the questionnaire to gain consensus regarding the relevancy and clarity of items, (3) determination of a range of possible scenarios for each item of the questionnaire and (4) evaluation of reliability. The flow of the study is described in figure 1. To the best of our knowledge, for example, through discussions with global experts in the field, currently there is no comprehensive validated questionnaire for evaluating the eHealth architecture components. Our study will provide fundamental information about the construction of the eHealth architecture, which may be used to guide the formulation of tailored NEHA in different settings.

Figure 1.

Breakdown of research phases. NEHA, national eHealth architecture.

The conceptual model

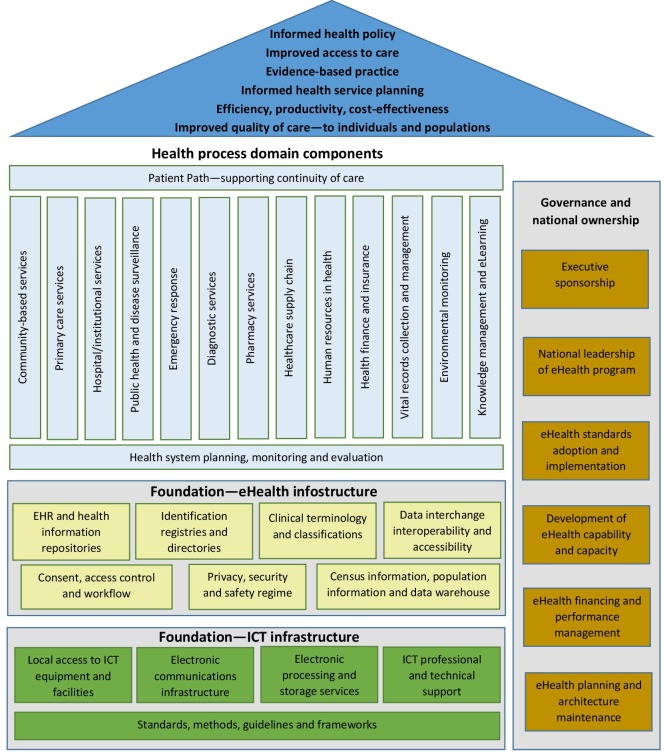

We will use the eHealth informatics—capacity-based eHealth architecture roadmap, developed by the International Organisation for Standardisation (ISO) (figure 2),25 as the main framework to construct the NEHA questionnaire. The framework comprises the following four general categories: (1) governance and national ownership, (2) eHealth infostructure, (3) ICT infrastructure and (4) health process domain (online supplementary appendix 1).

Figure 2.

eHealth architecture model according to ISO TR 14639—capacity-based eHealth architecture roadmap. EHR, electronic health record; ICT, information and communication technologies.

bmjopen-2018-022885supp001.pdf (282.3KB, pdf)

The planning committee

We have established a planning committee of six members: three experts in health policy and management, and three experts in eHealth and health informatics. The committee holds regular meetings, physical and mostly virtual, to design the research protocol, formulate various phases of study and approve the required material for data collection. The research phases have been prepared and approved, through consensus, by the planning committee. We anticipate that data collection will be completed by December 2018.

Patients and public involvement

We will not involve patients and any member of public during the development of this study protocol.

Phase 1: item generation

The first phase of the instrument development process will be generating a comprehensive list of items that can represent the various aspects of each component. The most important sources for item generation will be evidence review and experts’ opinions.

Source 1: evidence review

Reviewing the available evidence will enable us to identify the core items to inform the consensus-seeking process. Through discussions, the planning committee recommended three international documents for identification of the potential relevant items: (1) the eHealth informatics—capacity-based eHealth architecture roadmap developed by the ISO25; (2) the national eHealth strategy toolkit developed by the WHO—international telecommunications union26 and (3) the national health information system: an assessment tool, developed by the WHO.27 These documents were carefully examined and reviewed using the evaluation criteria for applicability and relevancy. Applicability refers to the extent to which the chosen items apply to eHealth architecture at the country-level setting. Relevancy refers to the extent to which the chosen items provide information that can be linked to each component. The identified items will be examined and translated into survey-format statements. Statements will be effectively written to ensure the clarity and conciseness based on the most important statement of each component that clearly represents the status of NEHA components.

Source 2: experts’ opinions

The panel of experts will be used as a second source of item generation and selection. The expert panel is a practical method for obtaining opinions on a given question. This procedure will help experts develop a broad range of items for each component. Using purposive sampling technique, we will recruit four eHealth international experts from academic, policy and clinical background, from both high-income countries and LMICs, who have in-depth knowledge and experiences in health informatics and eHealth policy.

During this stage, to design the preliminary version of the questionnaire, the overlaps will be identified and merged, while the wording of included items will be examined for clarity and relevancy. The items gathered through experts’ opinions will be evaluated and new items will be generated, refined and synthesised using the evaluation criteria of applicability, comprehensiveness and measurability in assessing the current status of the NEHA components.

One member of the research team (SMM) will be responsible for data collection and responding to, subject to the entire research team’s approval, the possible inquiries from the experts. We will email the experts with a link to the survey and invite them to provide their comments within 1 week. A reminder will be sent if the response is not obtained after 3 weeks. The questionnaire will be developed in English, together with the cover letter, the invitation and reminders.

Phase 2: validation of the questionnaire

Face validity

We will use qualitative methods (ie, sequential face-to-face review meetings and email correspondence) to determine face validity of the questionnaire. We will ask two experts from the planning committee to assess each item to decide about their ‘ambiguity’, ‘irrelevancy’ and ‘difficulty’.28 We will ask experts to perform the tasks listed in table 1.

Table 1.

Criteria to apply to items in making judgements in the face validity step

| Tasks | Description |

| Ambiguity | The extent to which an item is not open to more than one possible interpretation. |

| Relevancy | The extent to which an item would be relevance to its component. |

| Difficulty | The extent to which an item would be easily understood by readers. |

Content validity

Using Waltz and Bausell’s recommendation,29 we will use the Content Validity Index (CVI) to assess the content validity. The experts will evaluate the items based on a 4-point Likert scale on relevancy and clarity. The CVI value of 0.78 or above will be considered satisfactory for each item. To avoid overlooking the important items, we will also ask the experts to add limited extra items for each component (table 2).

Table 2.

Response scales used by the experts for rating the relevancy, clarity and missing items

| Relevancy | Clarity | Any missing item for each component? | |||

| Description | Scale | Description | Scale | Description | Scale |

| How important is the item | 1 = ‘not relevant’ | How clear is the wording | 1 = ‘not clear’ | Is there any item for each component that we have not included? | 1 = ‘no’ |

| 2 = ‘somewhat relevant’ | 2 = ‘somewhat clear’ | ||||

| 3 = ‘quite relevant’ | 3 = ‘quite clear’ | 2 = ‘yes’ | |||

| 4 = ‘highly relevant’ | 4 = ‘highly clear’ | ||||

Recruiting study participants

Using purposive sampling and snowball technique, we will invite (through email contact) selected international experts and scholars with academic, policy and clinical backgrounds, whom have expertise in various disciplines of eHealth to fill in the questionnaire. To enhance its applicability and social validity, we will ask purposefully selected consumer representatives at the international level to validate the questionnaire.

The procedure

The planning committee will finalise a package to be sent to participating scholars, that is, a brief background and description of study, the requirements for completing the task and the timeframe for completing the questionnaire. We will use the Limesurvey (http://www.limesurvey.org), which is an online open source survey application, to create the questionnaire, conduct the survey and perform the analysis. We will ask the participants to complete the questionnaire anonymously, while they can modify and add new items to the list or provide further commentary, using the free text space at the end of questionnaire.

Analysis

A member of planning committee (SMM) will independently scrutinise and transcribe data from the Limesurvey into IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, V.22.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp. The median score for all items will be calculated. For each item rated as ‘quite relevant/quite clear’ or ‘highly relevant/highly clear’, a value of 0.78 or above will be given. We will collate free text comments and conduct directed content analysis30 to capture the opinions expressed at the end of each questionnaire.

Phase 3: determination of a range of possible scenarios for each item

After the completion of analysis, we will convene a panel of experts to determine a range of possible scenarios for each item that is included in the questionnaire. The scenarios will be a descriptive example for each item under each of the four situations (high, medium, low and not at all), which will meet the gold standard of the conceptual model and will allow us to gather more complete and reliable information on the current status of NEHA within selected countries.

The selection process of the experts will be purposively congruent with this phase’s aims. The planning committee will design preliminary possible scenarios for each item. This will create inputs for the panel of experts to give their views about various scenarios for the situation relevant to each item. We will set an 80% agreement as an indication of acceptable consensus for each item.

Phase 4: evaluation of reliability

The final phase in designing and validating the questionnaire is evaluating the reliability, and doing so will allow us to start the development and implementation phase. In doing so, we will estimate the internal consistency by calculating Cronbach’s alpha coefficient, ranging from 0.0 to 1.0, with the cut-off point at 0.70, more than which is generally considered as an acceptable level for internal consistency.31

Discussion

This will be the first and most comprehensive study to design and validate the questionnaire on NEHA using the mixed-methods design. The findings are anticipated to be useful for all countries and international organisations who intend to assess, formulate, develop, implement and evaluate eHealth architecture. The findings will help establish a socio-technical basis, on which governmental and others concerned bodies can compare the policy interventions that boost the availability and utilisation of eHealth services. It is also valuable for governments to design and develop strategies and policies that could facilitate the adoption of eHealth and guide the use of ICTs towards the achievement of the desired goals.

Finally, this questionnaire will enable national evaluators to examine the extent to which the governments develop various components of eHealth architecture anywhere. Therefore, our study will contribute to the growing body of research that aims to create insights into the current status of eHealth architecture and identify the areas in need of improvement. As such, we hope that this study will open up further avenues to assess the status of eHealth architecture in different settings.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Patient consent for publication: Not required.

Contributors: AT was responsible for conception, design, implementation, analysis, drafting the manuscript and supervision of the whole process of this study. He is the principal investigator and guarantor. SMM is the principal researcher, who was involved in conception, development, implementation, data collection, analysis and writing of this manuscript. MT is the member of research team and responsible for intellectual development of manuscript as well as technical consultation for validating the questionnaire. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding: Tehran University of Medical Sciences (Grant No: 240-897).

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Ethics Committee for Research at the Tehran University of Medical Sciences.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Cline GB, Luiz JM. Information technology systems in public sector health facilities in developing countries: the case of South Africa. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2013;13:1313 10.1186/1472-6947-13-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Meeks DW, Takian A, Sittig DF, et al. Exploring the sociotechnical intersection of patient safety and electronic health record implementation. J Am Med Inform Assoc 2014;21:e28–34. 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Takian A. Envisioning electronic health record systems as change management: the experience of an English hospital joining the National Programme for Information Technology. Stud Health Technol Inform 2012;180:901–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Iacono T, Stagg K, Pearce N, et al. A scoping review of Australian allied health research in ehealth. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:543 10.1186/s12913-016-1791-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Murray E, May C, Mair F. Development and formative evaluation of the e-Health Implementation Toolkit (e-HIT). BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2010;10:61 10.1186/1472-6947-10-61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bujnowska-Fedak MM. Trends in the use of the Internet for health purposes in Poland. BMC Public Health 2015;15:194 10.1186/s12889-015-1473-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Cresswell KM, Worth A, Sheikh A. Actor-network theory and its role in understanding the implementation of information technology developments in healthcare. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2010;10:67 10.1186/1472-6947-10-67 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Domenichiello M. State of The Art in Adoption of E-Health Services in Italy in the context of European Union E-Government strategies. Procedia Economics and Finance 2015;23:1110–8. 10.1016/S2212-5671(15)00364-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Henriquez-Camacho C, Losa J, Miranda JJ, et al. Addressing healthy aging populations in developing countries: unlocking the opportunity of eHealth and mHealth. Emerg Themes Epidemiol 2014;11:136 10.1186/s12982-014-0021-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jarosławski S, Saberwal G. In eHealth in India today, the nature of work, the challenges and the finances: an interview-based study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2014;14:1 10.1186/1472-6947-14-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Price M, Lau F. The clinical adoption meta-model: a temporal meta-model describing the clinical adoption of health information systems. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2014;14:43 10.1186/1472-6947-14-43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Robertson AR, Nurmatov U, Sood HS, et al. A systematic scoping review of the domains and innovations in secondary uses of digitised health-related data. J Innov Health Inform 2016;23:611–9. 10.14236/jhi.v23i3.841 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Saleh S, Khodor R, Alameddine M, et al. Readiness of healthcare providers for eHealth: the case from primary healthcare centers in Lebanon. BMC Health Serv Res 2016;16:644 10.1186/s12913-016-1896-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Atkinson M. eHealth in Canada: current trends and future challenges. information and communications technology council. 2009.

- 15. Iljaž RJ, Meglič M, Svab I. Building consensus about eHealth in slovene primary health care: delphi study. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2011;11:25 10.1186/1472-6947-11-25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Marcelo AB, Marcelo PGF. eHealth Governance in the Philippines: state-of-the-Art. J of the International Society for Telemedicine and eHealth 2016;4:1–6. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Bagayoko CO, Dufour JC, Chaacho S, et al. Open source challenges for hospital information system (HIS) in developing countries: a pilot project in Mali. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2010;10:22 10.1186/1472-6947-10-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bukachi F, Pakenham-Walsh N. Information technology for health in developing countries. Chest 2007;132:1624–30. 10.1378/chest.07-1760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Mars M, Scott RE. Global e-health policy: a work in progress. Health Aff 2010;29:237–43. 10.1377/hlthaff.2009.0945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Okunhon I. A literature review on the impact of eHealth policies on the quality of health care: impact of ehealth policies in health care: Perspective from developed and developing Countries, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Deimazar G, Kahouei M, Zamani A, et al. Health information technology in ambulatory care in a developing country. Electron Physician 2018;10:6319–26. 10.19082/6319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Takian A, Cornford T. NHS information: revolution or evolution? Health Policy Technol 2012;1:193–8. 10.1016/j.hlpt.2012.10.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Adenuga OA, Kekwaletswe RM, Coleman A. eHealth integration and interoperability issues: towards a solution through enterprise architecture. Health Inf Sci Syst 2015;3:1 10.1186/s13755-015-0009-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Sheikh A, Cornford T, Barber N, et al. Implementation and adoption of nationwide electronic health records in secondary care in England: final qualitative results from prospective national evaluation in “early adopter” hospitals. BMJ 2011;343:d6054 10.1136/bmj.d6054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. International Standards Organization. ISO/TR 14639–2:2014(E) Health informatics — Capacity-based eHealth architecture roadmap — Part 2: Architectural components and maturity model. Geneva: ISO, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 26. World Health Organization. National eHealth strategy toolkit: international telecommunication union. 2012.

- 27. Health Metrics Network, World Health Organization. Assessing the national health information system: an assessment tool: World Health Organization, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Rahimi Kian F, Zandi A, Omani Samani R, et al. Development and validation of attitude toward gestational surrogacy scale in iranian infertile couples. Int J Fertil Steril 2016;10:113–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Waltz CF, Bausell BR. Nursing research: design statistics and computer analysis. Davis FA, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res 2005;15:1277–88. 10.1177/1049732305276687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lance CE, Butts MM, Michels LC. The sources of four commonly reported cutoff criteria: What did they really say? Organizational research methods 2006;9:202–20. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2018-022885supp001.pdf (282.3KB, pdf)