Abstract

Purpose

Migraine prevalence increases in people with obesity, and obesity may contribute to migraine chronicity. Yet, few studies examine the effect of comorbid migraine on health care utilization and expenses in obese US adults. This study aimed to identify risk factors for migraine and compare the use of health care services and expenses between migraineurs and non-migraineurs in obese US adults.

Subjects and methods

This 7-year retrospective study used longitudinal panel data from 2006 to 2013 from the Household Component of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey to identify obese adults reporting migraines. Outcomes compared in migraineurs vs non-migraineurs were as follows: annualized per-person medical care, prescription drug, and total health expenses.

Results

In 23,596 obese adults, 4.7% reported migraine (n=1,025) approximating 3 million civilian noninstitutionalized US individuals. Logistic regression showed that the following sociodemographic characteristics increased migraine risk: age (18–45 years), females, White race, poor perceived health status, and greater Charlson comorbidity index. Migraineurs showed US$1,401 (P=0.007), US$813 (P<0.001), and US$2,213 (P=0.001) greater annual medical, prescription drug, and total health expenses than non-migraineurs, respectively. After adjustment, total health expenses increased by 31.6% in migraineurs vs non-migraineurs.

Conclusion

In this US adult obese population, migraineurs showed greater total health care utilization and expenses than non-migraineurs. Treatment plans that address risk factors associated with migraine and comorbidities may help reduce the utilization of health care services and costs.

Keywords: migraine, obesity, health care expenses, utilization of health services

Introduction

Migraine is a type of headache with recurrent episodes, being unilateral location and varying in intensity. Migraine and obesity independently and significantly add personal and societal burden, diminish quality of life, and increase health care utilization. Migraine is often a comorbid condition among obese individuals.3–5 The overlapping central and peripheral pathways shared by obesity and migraine have been hypothesized as a potential mechanism to contribute to the association. Several studies suggest that multifactorial pathophysiological associations between migraine and obesity contribute to migraine prevalence in adults with obesity.3,6 The risk of episodic and chronic migraine increases as weight increases from normal to obese, with greater risk among the moribund obese, those with abdominal obesity, and in reproductive age groups. Obese women during their reproductive years represent a high-risk population associated with migraine occurrence.3,8,9

The US crude prevalence for obesity during years 2011–2014 is estimated as 36.5%, with greater prevalence among women, and increasing prevalence as people age.10 Obesity is associated with multiple chronic conditions1,11 and is cited as a risk factor for increased morbidity and mortality.12 Estimated health care costs among obese individuals range from US$147 billion to nearly US$210 billion per year.13 People with moderate or severe obesity are 1.8–4.0 times more likely to be prescribed medications than those with normal weight, and prescription drug costs were 40% higher among obese groups.14 Although migraine is underdiagnosed and under-treated in the US population,15 overall US migraine prevalence ~12%, with greater burden in females aged 18–44 years.16 The age-adjusted 1-year migraine prevalence in US adults is 16%.17 The direct costs associated with migraines are estimated as more than US$11 billion per year.18

Although obesity and migraine are common incapacitating conditions that increase the risk of cardiovascular events, and when present together share some common pathophysiological pathways,19 little information exists about the effect of comorbid migraine on patterns of health care utilization and expenses in obese individuals. Understanding outcomes in relation to costs will help build value-based information related to migraine in the obese population. Understanding characteristics and modifiable risk factors associated with migraines in obese adults may help researchers determine areas to develop into future interventions to improve treatment outcomes. This study aimed to identify sociodemographic factors associated with the occurrence of migraine and examine the effect of migraine on health care utilization and expenses in a national sample of US adults with obesity.

Subjects and methods

Data source

This retrospective study used longitudinal data from the Household Component of the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS; 2006–2013). The MEPS household component surveys a subsample of the US household from the previous years’ National Health Interview Survey. The survey’s panel design is composed of five rounds of interviews covering two calendar years for each independent panel. During the household interviews, MEPS collects detailed information from each member in the household, including sociodemographic characteristics, medical conditions and health status, health care utilization, medical care and prescription drug expenses, and insurance coverage. Subsequently, MEPS contacts the participant’s medical providers, health systems, and pharmacies to validate and give more detailed diagnosis, charge, expense, and payment information. Each panel provides a longitudinal weight that adjusts for survey attrition during the 2-year period and allows national estimates per panel in the analysis. This study used panels 11–17 for years 2006–2013 along with variables from the medical condition and event files to identify subjects with obesity and migraine. The institutional review board of Presbyterian College approved this study (PC201629).

Study population

The study population was composed of individuals who were 18 years and older and completed all five separate interviews during the 2-year period as evidenced by a longitudinal weight >0. Those with obesity were identified by a body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) ≥30, derived from the height and weight reported in the first round of the survey, calculated, and then coded by trained MEPS personnel.20 Those reporting one or more events of migraine were identified from the medical condition files by using the ICD, ninth revision, clinical modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnosis code for migraine “346”. MEPS recorded the medical conditions reported by survey participants and confirmed the diagnosis with the participants’ medical providers. The MEPS public use files preserve confidentiality by collapsing fully specified five-digit ICD-9-CM codes into three-digit codes. Adults with a BMI ≥30 reported in the first-round interview and followed for 2 years were included in the study. These eligible obese adults were then categorized by migraine status: 1) individuals reporting one or more episodes of migraine (termed migraineurs) and 2) individuals without migraine (termed non-migraineurs).

Outcome measures

Expense outcomes were average medical care, prescription drug, and total health expenses (per person per year). Total health expenses were calculated by summing medical care expenses in medical event files (ie, physician office, hospital and other outpatient, emergency department [ED], inpatient hospitalization, and others) and prescription drug expenses in the prescribed medicine files reported over the 2-year panel time frame.

Medical care and prescription drug expenses for any medical condition (defined as all-cause) as well as those specific to migraine were measured, respectively. Migraine-related medical utilization and expenses were limited to medical care and prescription drug expenses associated with the migraine ICD-9-CM diagnosis code “346”. Anti-migraine medication use and expenses were identified by Cerner MULTUM™/lexicon therapeutic classification codes in the prescribed medicine files. All expenses included the amounts paid by insurance and patients and were adjusted to US dollars in the year 2013 using the personal consumption expenditure health indexes.21

The proportions of people who sought migraine treatment in underweight, normal weight, overweight, obese, and severely obese groups were estimated. The total health expenses in overweight, obese, and severely obese groups with migraine were also compared.

Potential risk factors and covariates

The study included sociodemographic characteristics, perceived health status, and comorbidity variables to explore the potential risk factors associated with the occurrence of migraine. The regression models included the following commonly used sociodemographic MEPS variables: age, education, family size, gender, income, insurance coverage, marital status, and race. Participants who reported their general health in a perceived health status variable were categorized into five levels: excellent, very good, good, fair, and poor for analysis. In this study, the self-reported perceived health status was collapsed into three categories: excellent to very good, good, and fair to poor. To account for the severity of comorbidities, a comorbidity score was calculated for each participant using the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI). The CCI is a weighted index reflecting 19 diseases weighted (range 1–6) on their risk of mortality.22 ICD-9-CM codes were used to identify comorbidities from medical condition files.

Statistical analysis

Chi-squared test was used to compare the categorical characteristics of migraineurs vs non-migraineurs, and independent t-test was used to compare medical utilization and health care expenses between the two groups. Multivariate logistic regression was used to identify significant risk factors associated with the occurrence of migraine in the obese population. A generalized linear model with a log link and gamma distribution was applied to assess the effect of migraine on total health expenses by controlling for demographic and health-related covariates. The regression model was in the form of y (total health expenses) =β0+β1x1 (migraine, yes/no) +βnxn (covariates). Statistical significance was set a priori at P<0.05. All data analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). Estimates adjusted for the MEPS complex survey design and all statistical analysis applied longitudinal sampling weights.

Results

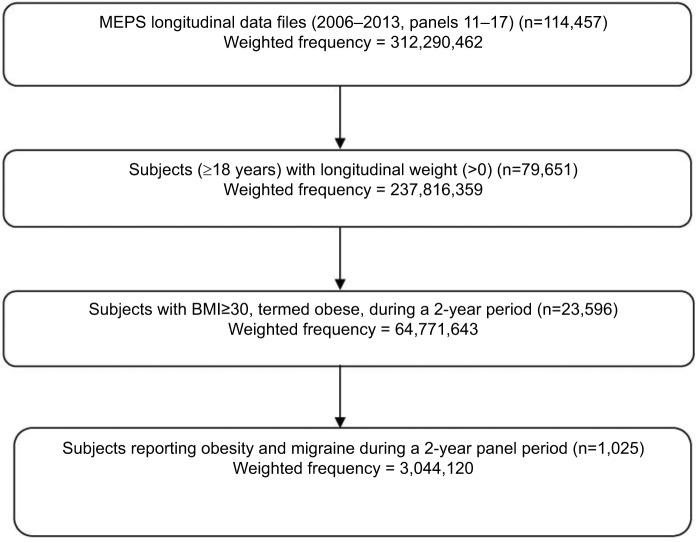

Among all adults, the proportions of people who sought medical care to treat migraine were 4.3% in underweight, 4.4% in normal weight, 3.5% in overweight, 4.4% in obese, and 6.2% in severely obese groups. Among the 23,596 obese US adults in MEPS longitudinal panels 11–17 for years 2006–2013, 4.7% (n=1,025) were identified with migraine, representing 3 million US individuals (Figure 1). Table 1 summarizes the obese adult study population’s characteristics. Compared with obese non-migraineurs, the obese migraineurs were proportionately more from younger age groups (18–45 years, 59.2% vs 44.9%, P<0.001), of female gender (79.5% vs 50.4%, P<0.001), unmarried (50% vs 44.3%, P=0.003), and reportedly of poor perceived health status (29.5% vs 21.2%, P<0.001). Table 2 summarizes the following significant factors associated with migraine occurrence in the US adult obese population: age, family size, gender, insurance coverage, race, perceived health status, and comorbidities. Adults aged 46–64 years were 45% (OR: 0.55, 95% CI: 0.45–0.66) and adults aged 65 years and older were 85% (OR: 0.15, 95% CI: 0.10–0.22) less likely to report migraine than those aged 18–45 years. Males were 75% (OR: 0.25, 95 CI: 0.20, 0.31) less likely to report migraine than females. The odds of migraine occurrence was 44% less for Blacks compared to Whites (OR: 0.56, 95% CI: 0.46, 0.69). Those who reported fair to poor perceived health status were 2.65 times (OR: 2.65, 95% CI: 1.34, 2.03) more likely to report migraine than those with very good to excellent perceived health status. A CCI of 1, or >1 vs CCI of 0, was 46% (OR: 1.46, 95% CI: 1.02, 2.07) or 32% (OR: 1.32, 95% CI: 1.07, 1.62) more likely to report migraine.

Figure 1.

Study population.

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; MEPS, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population by migraine status in adults with obesity from MEPS (2006–2013) (N=23,596)

| Variable | Subjects with migraine (n=1,025)

|

Subjects without migraine (n=22,571)

|

P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Weighted % | Weighted % | ||

|

| |||

| Age category (years) | <0.001 | ||

| 18–45 | 59.2 | 44.9 | |

| 46–64 | 35.6 | 38.8 | |

| 65+ | 5.2 | 16.2 | |

| Race | 0.024 | ||

| White | 72.6 | 68.2 | |

| Black | 10.6 | 13.5 | |

| Others | 16.8 | 18.3 | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 20.5 | 49.6 | <0.001 |

| Education | 0.23 | ||

| High school | 51.2 | 47.9 | |

| College | 23.5 | 26.0 | |

| No degree/others | 25.3 | 26.1 | |

| Family size | 0.92 | ||

| ≤2 | 57.1 | 57.3 | |

| >2 | 42.9 | 42.7 | |

| Geographical region | 0.032 | ||

| Northeast | 16.6 | 17.2 | |

| Midwest | 25.9 | 23.3 | |

| South | 43.7 | 39.8 | |

| West | 22.8 | 19.7 | |

| Marital status | |||

| Yes | 50.0 | 55.7 | 0.003 |

| Income categorya | 0.060 | ||

| Poor | 21.6 | 19.3 | |

| Low income | 17.4 | 14.8 | |

| Middle income | 29.5 | 32.5 | |

| High income | 31.5 | 33.4 | |

| Insurance coverage | 0.095 | ||

| Private | 68.7 | 66.1 | |

| Public | 19.4 | 18.8 | |

| Uninsured | 11.9 | 15.0 | |

| CCI | 0.32 | ||

| 0 | 67.3 | 69.3 | |

| 1 | 5.7 | 4.5 | |

| ≥2 | 27.0 | 26.2 | |

| Perceived health status | <0.001 | ||

| Excellent/very good | 38.1 | 45.9 | |

| Good | 32.4 | 32.8 | |

| Fair/poor | 29.5 | 21.2 | |

Note:

Poor is defined as income <100% of FPL; low income is defined as 100%– 199% of FPL; middle income is defined as 200%–399% of FPL; high income is defined as ≥400% of FPL.

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; FPL, federal poverty line; MEPS, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Table 2.

Factors associated with migraine in adults with obesity from MEPS (2006–2013) (N=23,596)

| Independent variable | Likelihood of migraine OR (95% CI) | P |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Age (years) | ||

| 18–45 | 1.00 | |

| 46–64 | 0.55 (0.45, 0.66) | <0.001 |

| ≥65 | 0.15 (0.10, 0.22) | <0.001 |

| Race | ||

| White | 1.00 | |

| Black | 0.56 (0.46, 0.69) | <0.001 |

| Others | 0.81 (0.64, 1.02) | 0.077 |

| Gender | ||

| Female | 1.00 | |

| Male | 0.25 (0.20, 0.31) | <0.001 |

| Education | ||

| College | 1.00 | |

| High school | 0.87 (0.70, 1.08) | 0.20 |

| No degree | 0.94 (0.78, 1.13) | 0.39 |

| Family size | ||

| ≤2 | 1.00 | |

| >2 | 0.82 (0.68, 0.98) | 0.034 |

| Geographical region | ||

| Northeast | 1.00 | |

| Midwest | 1.09 (0.85, 1.40) | 0.49 |

| South | 0.89 (0.71, 1.13) | 0.33 |

| West | 1.14 (0.88, 1.48) | 0.32 |

| Marital status | ||

| No | 1.00 | |

| Yes | 1.11 (0.93, 1.33) | 0.26 |

| Income categorya | ||

| High | 1.00 | |

| Middle | 0.87 (0.68, 1.12) | 0.26 |

| Low | 1.02 (0.78, 1.30) | 0.90 |

| Poor | 0.81 (0.65, 1.00) | 0.054 |

| Insurance coverage | ||

| Private | 1.00 | |

| Public | 0.89 (0.70, 1.13) | 0.39 |

| Uninsured | 0.65 (0.49, 0.85) | 0.002 |

| CCI | ||

| 0 | 1.00 | |

| 1 | 1.46 (1.02, 2.07) | 0.038 |

| ≥2 | 1.32 (1.07, 1.62) | 0.008 |

| Perceived health status | ||

| Excellent–very good | 1.00 | |

| Good | 1.20 (1.00, 1.45) | 0.050 |

| Fair–poor | 2.65 (1.34, 2.03) | <0.001 |

Note:

Poor defined is as income <100% of FPL; low income is defined as 100%–199% of FPL; middle income is defined as 200%–399% of FPL; high income is defined as ≥400% of FPL.

Abbreviations: CCI, Charlson comorbidity index; FPL, federal poverty line; MEPS, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.

Table 3 summarizes the comparison between migraineurs’ and non-migraineurs’ health care utilization patterns and expenses in obese US adults. Obese US adults with migraine showed greater physician office and ED visits and more prescriptions for medications than non-migraineurs (P<0.001). In migraineurs only 25.9% were prescribed antimigraine medications. Medical care utilization rather than prescribed medications was the driver behind higher total health expenses in migraineurs. Medical, prescription drug, and total health expenses in the migraine group were $1,401 (P=0.007), $813 (P<0.001), and $2,213 (P=0.001) higher than in the non-migraine group, respectively. Migraine-related expenses accounted for ~5% of the total health care expenses. No significance difference was observed in the frequency and expense of hospitalization between the groups. As summarized in Table 4, compared with the non-migraine group, total health expenses increased by 31.6% in the migraine group after controlling for sociodemographic and health-related variables.

Table 3.

Health service utilization patterns and expenses (per person per year) by migraine status in adults with obesity from MEPS (2006–2013) (N=23,596)

| Health service utilization and expenses | Subjects with migraine (n=1,025) | Subjects without migraine (n=22,571) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| All-cause health service utilization | |||

| Number of office visits, mean (SE) | 10.2 (0.5) | 4.2 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| Number of outpatient visits, mean (SE) | 0.8 (0.1) | 0.3 (0.0) | <0.001 |

| Number of prescription fills, mean (SE) | 25.0 (1.2) | 18.3 (0.3) | <0.001 |

| ED visits per 1,000 patient months | 37.8 | 18.8 | <0.001 |

| Hospitalization per 1,000 patient months | 13.9 | 11.3 | 0.078 |

| Migraine-related health service utilization | |||

| Number of office visits, mean (SE) | 0.5 (0.0) | ||

| Number of prescriptions, mean (SE) | 0.6 (0.0) | ||

| ED visits per 1,000 patient months | 4.2 | ||

| Hospitalization per 1,000 patient months | 0.2 | ||

| Antimigraine medication use, % | 25.9 | ||

| Triptan | 85.9 | ||

| Others | 16.9 | ||

| All-cause health expenses ($), mean (SE) | |||

| Medical expensesa | 6,288 (522) | 4,887 (106) | 0.007 |

| Office | 2,205 (159) | 1,497 (36) | <0.001 |

| Outpatient | 1,009 (236) | 607 (30) | <0.001 |

| ED | 452 (38) | 233 (8) | <0.001 |

| Hospitalization | 1,994 (332) | 1,936 (66) | 0.86 |

| Others | 628 (60) | 614 (23) | 0.81 |

| Prescription drugs | 2,451 (210) | 1,638 (37) | <0.001 |

| Total expensesb | 8,739 (638) | 6,526 (125) | 0.001 |

| Migraine-related health expenses ($), mean (SE) | |||

| Medical expensesc | 282 (31) | ||

| Office | 149 (21) | ||

| Outpatient | 31 (8) | ||

| ED | 73 (11) | ||

| Hospitalization | 29 (12) | ||

| Prescription drugs | 145 (28) | ||

| Total expensesd | 427 (34) | ||

Notes:

Medical expenses included outpatient, ED, hospitalization, and other expenses.

Total expenses were the sum of medical and prescription expenses.

Medical expenses included outpatient, ED, and hospitalization expenses associated with migraine.

Total expenses were the sum of medical and prescription expenses associated with migraine.

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; MEPS, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; SE, standard error.

Table 4.

Effect of migraine on total health expenses in adults with obesity from MEPS (2006–2013) (N=23,596)

| Independent variable | Estimated log coefficienta(SE) | Change in percentageb | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Migraine | ||||

| Yes (vs no) | 0.27 (0.05) | +31.6 | <0.001 | |

| Age (years) | ||||

| 18–45 | Reference | |||

| 46–64 | 0.39 (0.04) | +47.6 | <0.001 | |

| ≥65 | 0.45 (0.05) | +56.8 | <0.001 | |

| Race | ||||

| White | Reference | |||

| Black | −0.07 (0.07) | −6.8 | 0.30 | |

| Others | −0.05 (0.04) | −4.9 | 0.21 | |

| Gender | ||||

| Female (vs male) | 0.36 (0.04) | +43.3 | <0.001 | |

| Education | ||||

| College | Reference | |||

| High school | 0.10 (0.04) | +10.5 | 0.008 | |

| No degree | −0.01 (0.05) | −1.0 | 0.92 | |

| Family size | ||||

| >2 (vs ≤2) | −0.25 | −28.4 | <0.001 | |

| Geographical region | ||||

| Northeast | Reference | |||

| Midwest | −0.03 (0.05) | −2.9 | 0.62 | |

| South | −0.17 (0.05) | −15.6 | 0.001 | |

| West | −0.19 (0.06) | −17.3 | 0.001 | |

| Marital status | ||||

| Yes (vs no) | 0.11 (0.04) | +11.6 | 0.010 | |

| Income | ||||

| High | Reference | |||

| Middle | −0.27 (0.07) | −23.7 | <0.001 | |

| Low | −0.25 (0.07) | −22.1 | 0.001 | |

| Poor | −0.11 (0.05) | −10.4 | 0.043 | |

| Insurance coverage | ||||

| Private | Reference | |||

| Public | 0.11 (0.05) | +11.6 | 0.012 | |

| Uninsured | −0.89 (0.09) | −58.9 | <0.001 | |

| Comorbidity | ||||

| 0 | Reference | |||

| 1 | 0.71 (0.07) | +103.4 | <0.001 | |

| ≥2 | 0.90 (0.04) | +145.9 | <0.001 | |

| Perceived health status | ||||

| Excellent–very good | Reference | |||

| Good | 0.27 (0.05) | +30.9 | <0.001 | |

| Fair–poor | 0.76 (0.05) | +114 | <0.001 | |

Notes:

Generalized linear model with log link and gamma distribution assessed the association between all-cause total health expenses and migraine, adjusting for age, gender, race, marital status, family size, education, poverty line, insurance coverage, comorbidity, and perceived health status.

The estimated log coefficients were interpreted as a percent change in expense in obese adults.

Abbreviations: MEPS, Medical Expenditure Panel Survey; SE, standard error.

Among the adults with migraine, the total health expenses in the severely obese group ($10,506) were significantly higher than the obese ($8,302) and overweight ($7,333) groups (P<0.01).

Discussion

This study described the characteristics and examined the utilization of health services and expense outcomes of obese US adults with and without migraine. The study found that 4.7% of obese adults reported migraine when they sought medical care, a figure much lower than migraine disease prevalence in the obese population (20%–25%) and as found in the general US population (12%–16%).6,8,23 This suggests that most people with migraines do not consult physicians. Similar findings were reported by previous studies using MEPS data.24,25 In addition, sociodemographic factors (age, family size, gender, insurance coverage, and race), perceived health status, and those with higher comorbidity scores were associated with the occurrence of migraine in the obese population. Moreover, increased outpatient utilization, prescription medication use, and total health expenses were observed in the migraine group.

This study showed that among obese US adults, older age, Black race, and being uninsured were significant factors associated with lower likelihood of reporting migraine. Being female, having fair to poor health status, and higher comorbidity increased the likelihood of reporting migraine. First, age and gender are known risk factors associated with migraine in the general population. Several studies report migraine as more common in women (17.6%) than men (6.5%), and most prevalent during the reproductive years (20–50 years).26–29 A meta-analysis suggests that the association between obesity and migraine is mediated by gender.30 In our study, similar effects of age and gender on migraine occurrence were found in this obese population. Second, the results from this study differ from previous research by showing racial disparities among migraineurs in the obese population. Plesh et al’s31 study showed that severe headache or migraine prevalence did not significantly vary among White and Black adults. However, our findings are consistent with Nicholson et al’s32 study, comparing White and African Americans that showed the following disparities: lower proportions using a health care setting for migraine treatment (46% vs 72%), reporting a headache diagnosis (47% vs 70%), and being prescribed antimigraine drugs (14% vs 37%). Similarly, uninsured individuals were less likely to seek medical care for a headache than those covered by public or private insurance. This may partially explain the lower likelihood of reported migraine in the MEPS medical events. Thus, migraine may be underdiagnosed and undertreated in Black or uninsured obese adults. Finally, our study showed obese adults with poor health status and more severe comorbidities as more likely to have migraine. Obesity is a risk factor for various chronic diseases.33,34 Some conditions, such as depression, are also associated with migraine occurrence.35,36 Managing comorbid conditions in the obese population may help prevent or reduce migraine onset.

In this study, migraine-related health expenses accounted for only 5% of total health expenses, a figure that did not significantly contribute to the difference in total health expenses between the migraine and non-migraine groups. Often, individuals use nonpharmacological therapy or over-the-counter (OTC) medications as a first-line approach to self-treat migraines and reserve medical headache care for more severe migraines.37 In addition, this study showed that only 26% of adult migraineurs used antimigraine prescription medications for treatment, suggesting that migraine may be undertreated. Similar to our health care utilization results, another survey study looking at headache in health care workers reported that 22% sought medical care for headache/migraine and 22% and 65% used prescription and OTC drugs to treat migraines, respectively.37 Although this study showed that migraine-related health expenses did not impact total health care expenses, total health expenses increased by >30% in the obese group with migraine. Health care utilization and expenses in our migraine vs non-migraine groups predominantly related to outpatient services and prescription drug use. This study’s health services utilization results imply that the ambulatory care setting where primary care providers treat headache may be a good place to assess the impact of interventions targeting comorbidities on migraine occurrence in obese adults. Moreover, other previous researches indicate a positive association between the rate of obesity, prevalence of chronic conditions, and health care spending.38 Obese people consume a higher amount of direct medical care costs than nonobese people.39 More fully incorporating comorbidity management into headache care may improve health and economic outcomes.

Some limitations should be considered when reading the results. MEPS longitudinal files estimate the treatment prevalence of a disease as derived from the medical events, thereby preventing the findings from being used as a measure of disease prevalence. The migraine treatment prevalence in our study is less than the migraine disease prevalence reported in epidemiological studies. Second, this study reflects a point in time for years 2006–2013, allowing the results to show relationships but not causality. Third, confidentiality concerns require the MEPS public use files to mask fully specified diagnosis, limiting the study’s ability to identify subtypes of migraine to reflect the disease severity or distinguish between episodic or chronic migraine. Fourth, MEPS does not provide clinical measures of migraine severity. Additional research using data with fully specified diagnosis codes could enhance our findings. Fifth, MEPS panel interviews occur over 2 years in a short-term time frame. More research is required to explore long-term effects. Finally, our study assessed the effect of a migraine on direct medical costs. The impacts of a migraine on indirect costs and quality of life in the adult obese population were not evaluated.40,41

The results hold several implications for health care providers in practice. The study’s obese adult population’s overall characteristics differed between migraineurs vs non-migraineurs. This study adds to our understanding of migraine in a distinct subpopulation: obese adults. Since migraine and obesity often coexist, it is important to disentangle factors that contribute to migraine, add to the cost of care, and influence health care use. Knowing the risk factors for comorbid migraine could help medical providers tailor prevention and treatment strategies for obese adults by incorporating comorbidity management. Understanding risk profiles of obese migraineurs may help with clinical decision-making about how to tailor preventive strategies or who to enroll in disease management programs. Moreover, the findings should also interest policy makers. Comorbid migraine among obese US adults significantly impacted health care utilization and total health care expenses. Outpatient expenses accounted for a large proportion of the total health expenses and contributed to the significant difference in health care expenses. Ambulatory care models that improve health outcomes while controlling costs could focus on approaches to comorbid migraine in obese adults. In addition, mid-level providers practicing to the full extent of their license, such as nurse practitioners practicing in ambulatory care settings, are well positioned to address factors associated with migraine and tailor disease management strategies to account for comorbid migraine in obese adults.

Conclusion

Among obese US adults, increased total health care utilization and expenses were shown in those with migraine. Addressing risk factors associated with migraine and considering treatment for comorbidities could help reduce total health expenses. Future research could compare treatment plans that include interventions to prevent migraine vs conventional treatment and further assess the utilization of health services and cost outcomes.

Footnotes

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Vogeli C, Shields AE, Lee TA, et al. Multiple chronic conditions: prevalence, health consequences, and implications for quality, care management, and costs. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(Suppl 3):391–395. doi: 10.1007/s11606-007-0322-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chai NC, Scher AI, Moghekar A, Bond DS, Peterlin BL. Obesity and headache: Part I – a systematic review of the epidemiology of obesity and headache. Headache. 2014;54(2):219–234. doi: 10.1111/head.12296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peterlin BL, Rapoport AM, Kurth T. Migraine and obesity: epidemiology, mechanisms, and implications. Headache. 2010;50(4):631–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01554.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pavlovic JM, Vieira JR, Lipton RB, Bond DS. Association between obesity and migraine in women. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2017;21(10):41. doi: 10.1007/s11916-017-0634-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gelaye B, Sacco S, Brown WJ, Nitchie HL, Ornello R, Peterlin BL. Body composition status and the risk of migraine: A meta-analysis. Neurology. 2017;88(19):1795–1804. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chai NC, Bond DS, Moghekar A, Scher AI, Peterlin BL. Obesity and headache: part II – potential mechanism and treatment considerations. Headache. 2014;54(3):459–471. doi: 10.1111/head.12297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bigal ME, Liberman JN, Lipton RB. Obesity and migraine: a population study. Neurology. 2006;66(4):545–550. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000197218.05284.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford ES, Li C, Pearson WS, Zhao G, Strine TW, Mokdad AH. Body mass index and headaches: findings from a national sample of US adults. Cephalalgia. 2008;28(12):1270–1276. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2008.01671.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vo M, Ainalem A, Qiu C, Peterlin BL, Aurora SK, Williams MA. Body mass index and adult weight gain among reproductive age women with migraine. Headache. 2011;51(4):559–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2010.01833.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief. 2015;219:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bauer UE, Briss PA, Goodman RA, Bowman BA. Prevention of chronic disease in the 21st century: elimination of the leading preventable causes of premature death and disability in the USA. Lancet. 2014;384(9937):45–52. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60648-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnson NB, Hayes LD, Brown K, Hoo EC, Ethier KA, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) CDC national health report: leading causes of morbidity and mortality and associated behavioral risk and protective factors—United States, 2005–2013. MMWR Suppl. 2014;63(4):3–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cawley J, Meyerhoefer C. The medical care costs of obesity: an instrumental variables approach. J Health Econ. 2012;31(1):219–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teuner CM, Menn P, Heier M, Holle R, John J, Wolfenstetter SB. Impact of BMI and BMI change on future drug expenditures in adults: results from the MONICA/KORA cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:424. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-13-424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Diamond S, Bigal ME, Silberstein S, Loder E, Reed M, Lipton RB. Patterns of diagnosis and acute and preventive treatment for migraine in the United States: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study. Headache. 2007;47(3):355–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smitherman TA, Burch R, Sheikh H, Loder E. The prevalence, impact, and treatment of migraine and severe headaches in the United States: a review of statistics from national surveillance studies. Headache. 2013;53(3):427–436. doi: 10.1111/head.12074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pleis JR, Ward BW, Lucas JW. Summary health statistics for U.S. adults: National health interview survey, 2009. Vital Health Stat 10. 2010;249:1–207. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hawkins K, Wang S, Rupnow M. Direct cost burden among insured US employees with migraine. Headache. 2008;48(4):553–563. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2007.00990.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bigal ME, Lipton RB, Holland PR, Goadsby PJ. Obesity, migraine, and chronic migraine: possible mechanisms of interaction. Neurology. 2007;68(21):1851–1861. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000262045.11646.b1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stagnitti M, homepage on the Internet Trends in health care expenditures by body mass index (BMI) category for adults in the US civilian noninstitutionalized population, 2001 and 2006. Statistical Brief #247. Jul, 2009. [Accessed April 24, 2018]. [cited January 22, 2018] Available from: https://meps.ahrq.gov/data_stats/Pub_ProdResults_Details.jsp?pt=Statistical+Brief&opt=2&id=909.

- 21.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [homepage on the Internet] Using appropriate price indices for analyses of health care expenditures or income across multiple years. 2017. Apr, [Accessed April 24, 2018]. [cited January 22, 2018] Available from: https://meps.ahrq.gov/about_meps/Price_Index.shtml.

- 22.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–619. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bond DS, Roth J, Nash JM, Wing RR. Migraine and obesity: epidemiology, possible mechanisms and the potential role of weight loss treatment. Obes Rev. 2011;12(5):e362–e371. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-789X.2010.00791.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wu J, Davis-Ajami ML, Kevin Lu Z. Impact of depression on health and medical care utilization and expenses in US adults with migraine: a retrospective cross sectional study. Headache. 2016;56(7):1147–1160. doi: 10.1111/head.12871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu J, Noxon V, Lu ZK. Patterns of use and health expenses associated with triptans among adults with migraines. Clin J Pain. 2015;31(8):673–679. doi: 10.1097/AJP.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lipton RB, Bigal ME, Diamond M, et al. Migraine prevalence, disease burden, and the need for preventive therapy. Neurology. 2007;68(5):343–349. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000252808.97649.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burch RC, Loder S, Loder E, Smitherman TA. The prevalence and burden of migraine and severe headache in the United States: updated statistics from government health surveillance studies. Headache. 2015;55(1):21–34. doi: 10.1111/head.12482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, et al. The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(3):193–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01288.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jensen R, Stovner LJ. Epidemiology and comorbidity of headache. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(4):354–361. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70062-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ornello R, Ripa P, Pistoia F, et al. Migraine and body mass index categories: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Headache Pain. 2015;16(1):27. doi: 10.1186/s10194-015-0510-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plesh O, Adams SH, Gansky SA. Racial/ethnic and gender prevalences in reported common pains in a national sample. J Orofac Pain. 2011;25(1):25–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nicholson RA, Rooney M, Vo K, O’Laughlin E, Gordon M. Migraine care among different ethnicities: do disparities exist? Headache. 2006;46(5):754–765. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4610.2006.00453.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pratt LA, Brody DJ. Depression and obesity in the US adult household population, 2005–2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2014;167:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Preiss K, Brennan L, Clarke D. A systematic review of variables associated with the relationship between obesity and depression. Obes Rev. 2013;14(11):906–918. doi: 10.1111/obr.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bruti G, Magnotti MC, Iannetti G. Migraine and depression: bidirectional co-morbidities? Neurol Sci. 2012;33(S1):107–109. doi: 10.1007/s10072-012-1053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rist PM, Schürks M, Buring JE, Kurth T, Migraine KT. Migraine, headache, and the risk of depression: prospective cohort study. Cephalalgia. 2013;33(12):1017–1025. doi: 10.1177/0333102413483930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hughes MD, Wu J, Williams TC, et al. The experience of headaches in health care workers: opportunity for care improvement. Headache. 2013;53(6):962–969. doi: 10.1111/head.12069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Allen L, Thorpe K, Joski P. The effect of obesity and chronic conditions on Medicare spending, 1987–2011. Pharmacoeconomics. 2015;33(7):691–697. doi: 10.1007/s40273-015-0284-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.An R. Health care expenses in relation to obesity and smoking among U.S. adults by gender, race/ethnicity, and age group: 1998–2011. Public Health. 2015;129(1):29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2014.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gilligan AM, Foster SA, Sainski-Nguyen A, Sedgley R, Smith D, Morrow P. Direct and indirect costs among United States commercially insured employees with migraine. J Occup Environ Med. 2018 Sep 5; doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000001450. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Messali A, Sanderson JC, Blumenfeld AM, et al. Direct and indirect costs of chronic and episodic migraine in the United States: a web‐based survey. Headache. 2016;56(2):306–322. doi: 10.1111/head.12755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]