Abstract

The purpose of this article is to describe a case of an accidental turbinectomy during nasal intubation for an elective oral and maxillofacial surgical case that was confirmed after extubation. While there are several reported cases, this still tends to be an overall rare complication in the field of anesthesia. This article highlights the complications encountered due to turbinectomy while also identifying causes, signs, and methods to prevent it.

Key Words: Obstruction, Inferior turbinectomy, Nasotracheal intubation, General anesthesia

The nasal intubation technique first described in 1902 by Kuhn1 has been the most commonly desired method of intubation for most maxillofacial surgical procedures. It is paramount for the anesthesiologist to have a strong foundation in the nasal anatomy to adequately understand the pathways of the endotracheal tube (ETT) and the associated complications during nasotracheal intubation.1 Each patient is thoroughly assessed and examined to determine the potential risks to nasotracheal intubation versus oral intubation. The reported contraindications to nasal intubation have been: large nasal polyps, midface instability, suspected basilar skull fractures, recent nasal surgery, history of frequent episodes of epistaxis, and coagulopathy.1 The upper and lower compartments are the 2 anatomical pathways for insertion of the ETT through the nasal cavity.1 The lower pathway lies along the floor of the nasal cavity and the upper lies inferiorly to the middle turbinate.1 This presents an important consideration as the upper pathway can lead to more significant complications if the middle turbinate is injured or avulsed. These complications include massive epistaxis, cerebrospinal fluid rhinorrhea, or olfactory nerve damage.2 It has been reviewed that partial or complete obstruction of the ETT can occur due to an inadvertent turbinectomy during intubation. In some instances, the diagnosis was only made following extubation. This case report will discuss complications, signs, and methods of prevention in accidental turbinectomy during nasal intubation only diagnosed following extubation.

CASE REPORT

An 18-year-old male with no significant past medical history presented to the emergency department status post a fall and loss of consciousness 24 hours prior. After ruling out any other physical trauma including brain or cervical spine injury, the patient was referred to the department of oral and maxillofacial surgery for examination. It was found after radiographic and clinical examination that the patient sustained a left subcondylar fracture with malocclusion needing surgical intervention. Closed reduction via maxillomandibular fixation under general anesthesia was planned and informed consent was obtained. Preanesthetic evaluation was performed and no gross abnormalities found on physical exam and airway exam. The patient showed a maximal incisal opening of approximately 30 mm with associated pain. There was no gross septal abnormalities or deviations. The patient was classified as American Society of Anesthesiologists grade 1.

The patient was taken to the operating room and placed in supine position on the operating table. The patient was initially given Versed 4 mg and 50 mcg fentanyl for light sedation. The patient was given 100% oxygen via facemask for approximately 3 minutes and saturation was maintained at 100%. The patient was then induced via propofol and neuromuscular blockade was achieved after proper ventilation was confirmed. Two percent xylocaine jelly was introduced into the right nostril along with a nasal trumpet. After removal of the nasal trumpet, a 7.0 nasal RAE ETT lubricated with 2% xylocaine jelly was introduced into the right nostril with moderate resistance. The left nostril was then attempted also being met with moderate resistance. Placement of the tube was ultimately achieved through the right nostril with remarkable epistaxis. High volume suction was performed and the bleeding was controlled with external pressure on the nose. After hybrid archbars were secured to the maxilla and mandible via 6 mm screws, a slow ooze of heme was noted coming into the posterior oropharynx and from the right nares. It was decided to not place the patient into maxillomandibular fixation at this time, and the patient was handed over to anesthesia for extubation. Upon extubation, bleeding continued from the right nares, which was controlled with external pressure for 5 minutes and the nares were packed with cotton pledgets soaked in phenylephrine. The attending of oral surgery examined the ETT and notified the anesthesiologist of his finding of what appeared to be the nasal turbinate firmly lodged within the tube partially occluding the orifice. The anesthesiologist then reported that he did note elevated airway pressures throughout the case but did not mention it to the surgical team as satisfactory oxygen saturation was still being maintained throughout the case.

The patient was taken to the post anesthesia care unit (PACU) where the otolaryngologist (ENT) on call was notified of the event. ENT agreed to see the patient for follow-up as an outpatient in their office. The patient was reassessed in the PACU. The nasal packing was gently removed and the nostrils were examined with a nasal speculum. No further bleeding was noted coming from either nostril or intraorally. The patient was hemodynamically stable and it was decided at that time to not repack the nose. The event was discussed with the patient and the patient's father who understood and agreed to follow-up with ENT as well. The patient was stable for discharge and went home the same day. The patient followed up in the oral surgery clinic 1 week postoperatively and reported no acute events or complaints related to the surgery or the nasal trauma. The patient had yet to follow-up with ENT and was advised to follow-up. The patient had the elastics removed after the 2-week follow-up with a stable and reproducible occlusion. The patient then failed to return until 7 weeks later for removal of the hybrid archbars. The patient again never followed up with ENT as advised but reported no acute events or complaints. The patient denied any nasal complications, bleeding, or obstructions. The patient never returned for future follow-ups and to the best of our knowledge never reported to ENT for a follow-up evaluation.

DISCUSSION

Nasal intubation has been the most preferred method of intubation in the maxillofacial setting due to the optimal accessibility and visibility of the oral surgical field. With nasal intubation, multiple complications arise, which can range from minor to severe complications. Complications include avulsed inferior turbinates,3 avulsed middle turbinates,2 massive epistaxis,2 obstruction of the ETT, and aspiration of foreign objects into the bronchi.4 When it comes to avulsion, the inferior turbinate tends to be the more commonly injured or avulsed structure due to its anatomical location. According to Williams et al,2 middle turbinate avulsion can be due to a more superior path of insertion of the tube as opposed to posterior and perpendicular to the face.

In the case reported by Williams et al,2 the avulsed middle turbinate was immediately diagnosed and removed at the base of the vocal cords. ENT was consulted and it was verified that there was no cerebrospinal fluid leak and endoscopic cautery of the middle turbinate stalk was performed after the surgery was completed. It is important to note that after the avulsed turbinate was diagnosed, the same nares were re-intubated to complete the case as opposed to a new attempt in the opposite nostril.2 It is said that the tube also serves a tamponade to minimize the bleeding from the affected nares.2

With an avulsed turbinate after intubation, a major complication that can result is either partial or complete obstruction of the ETT or obstruction due to displacement of the turbinate into the bronchi. Clinical signs should register with the anesthesiologist that there is a mechanical obstruction somewhere along the airway. It must then be verified whether the obstruction is within the ETT. In the case presented by Knuth and Richards,4 the inferior turbinate obstructing in the left mainstem bronchus showed several signs and symptoms that alerted the clinicians of a possible obstruction. Clinical signs included: difficult ventilation, possible increased end-tidal CO2, increased peak inspiratory pressures, and decreased breath sounds on the left side.4 Even with suctioning of ETT and placement of a chest tube, the left lung showed no resolution and verified no obstruction of the ETT.4 Chest radiographs showed an elevated left hemidiaphragm with lower left lobe atelectasis.4

Recommendations and techniques to avoid these complications associated with nasal trauma and turbinate avulsion have been documented in the literature. Current techniques include using an appropriate sized tube, choosing the most patent nares, and never applying excessive force to push a tube down the nasal pathway (if resistance is met, retreat and try again or try opposite nares).4 In addition, vasoconstrictors and lubrication of the tube and nostril prior to intubation can help prevent these complications.3 A detailed preanesthetic evaluation prior to the procedure is also paramount to evaluate the patient and airway and to note any discrepancies such as a deviated septum.3 Additional methods have been documented in the literature to reduce nasal trauma and avoidance of turbinate injury. Delgado et al5 reports that on a patient with factor IX deficiency, using a red rubber catheter attached to the tip of the ETT to gently guide the tube through the nasal pathway into the oropharynx helped prevent traumatic insult. The main disadvantage discussed with the red rubber catheter is any patient with a latex allergy.5 Thermosoftening of the tracheal tube has also been reported as an added benefit to reduce nasal trauma.5 Wong et al6 in a similar fashion reports attaching a urethral catheter to the tip of the ETT to promote safe and atraumatic passage through the nasal cavity.

There are several treatment therapies to manage epistaxis. Treatment modalities include topical vasoconstriction, chemical/electrocautery, nasal packing, a Foley catheter, and arterial ligation or embolization.7 Initial management entails direct compression along with packing the affected nostril with gauze or cotton soaked in a vasoconstrictor.7 Direct pressure can be applied from 5 to 20 minutes along with tilting the head forward to prevent pooling of blood in the posterior pharynx.7 In anterior epistaxis, there are several nasal packing options one can employ. As was performed in our case, cotton pledgets soaked in phenylephrine can be placed in the anterior nasal cavity with direct pressure applied to the nose for at least 5 minutes.7 Other options include hemostatic absorbable packings such as Gelfoam or Surgicel. Alternatively, a preformed nasal tampon such as the Merocel packing coated in bacitracin or lubricant jelly can be inserted along the floor of the nose, where it expands after several drops of saline solution or topical vasoconstrictor applied to it.7 A posterior packing may be accomplished by passing a catheter through 1 nostril, passing through the nasopharynx and out through the mouth. The nasal packs are generally left from 2 to 5 days and then removed.7 Due to possibility of toxic shock syndrome, the use of antistaphylococcal antibiotics are recommended for these patients.

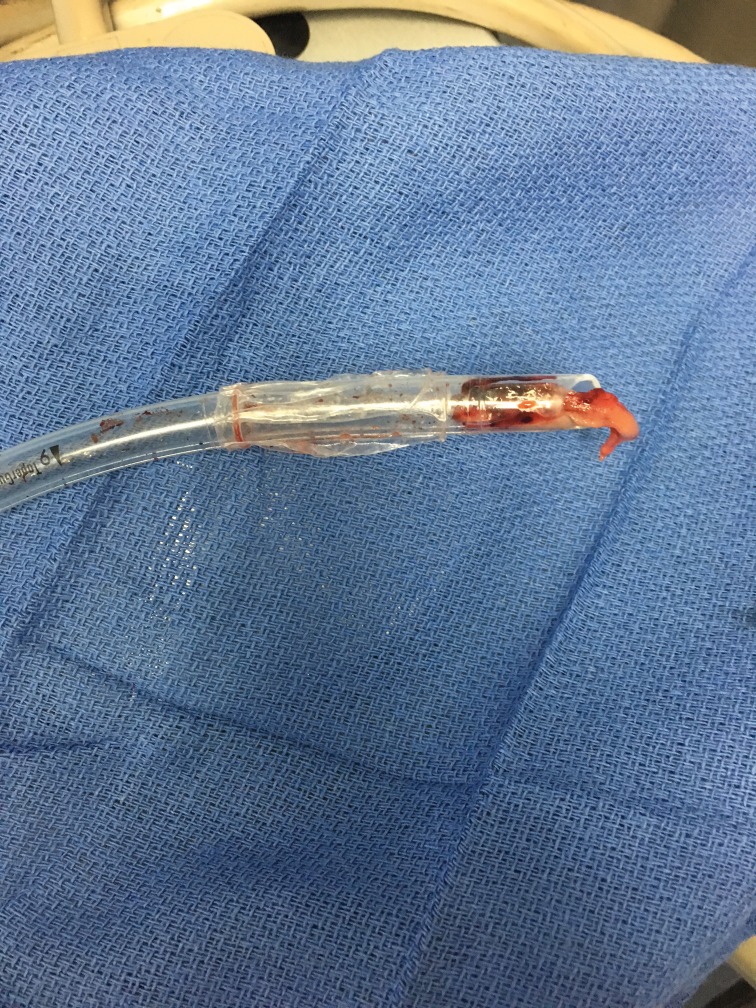

This article reports a complete avulsion of the inferior turbinate, which became firmly occluded within the ETT causing partial obstruction. This finding was only diagnosed at the end of the case following extubation. The mass was removed from the tube and inspected as shown in Figure 2. At the time of intubation, there was moderate resistance encountered in both nostrils and remarkable bleeding was noted, which was subsequently arrested and the case completed. Although the anesthetist did find an increase in peak pressures, satisfactory oxygen saturation was maintained and therefore no other action was taken from the anesthesiologist. Fortunately, the avulsed turbinate, as depicted in Figure 1, was firmly occluded within the tube and did not get displaced into the main bronchial stem. The exact cause for the avulsion though not certain likely stemmed from above threshold pressure while introducing the nasotracheal tube, which was met with moderate resistance. The patient recovered uneventfully after the procedure and was discharged home the same day with appropriate postop instructions.

Figure 2.

Avulsed turbinate removed from endotracheal tube (ETT).

Figure 1.

Avulsed inferior turbinate occluded in nasotracheal tube.

CONCLUSION

Nasotracheal intubation is recognized as the preferred method of intubation for most oral and maxillofacial procedures in the operating room setting. Minor and major complications can arise, which can be avoided with proper technique and patient management. Although rare, accidental turbinectomy is a complication that can arise upon nasal intubation. The main techniques practiced to avoid these complications are to avoid applying above threshold pressure, lubricating the nostril and tube and the use of vasoconstrictors. However, if obstruction of a foreign body has occurred in the tube such as in this case, one must pay close attention to the clinical signs to be alerted that a possible obstruction has occurred somewhere along the airway. If there is any suspicion of any nasal trauma or injury to the turbinates, it is recommended to attempt evaluating the tube in the oropharynx to verify no foreign body before advancing the tube through the vocal cords.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The author acknowledges the contribution of Dr. Harry Dym, Director and Chairman of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery, The Brooklyn Hospital Center.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chauhan V, Acharya G. Nasal intubation: a comprehensive review. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2016;20:662–667. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.194013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams AR, Burt N, Warren T. Accidental middle turbinectomy: a complication of nasal intubation. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:1782–1784. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199906000-00039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Prasanna D, Mazumdar U, Bhat S, Nigam N, Jain S. Inferior turbinectomy: an unusual presentation of complication of nasotracheal intubation. J Orofac Res. 2012;2:61–63. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knuth TE, Richards JR. Mainstem bronchial obstruction secondary to nasotracheal intubation: a case report and review of the literature. Anesth Analg. 1991;73:487–489. doi: 10.1213/00000539-199110000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Delgado A, Sanders J. A simple technique to reduce epistaxis and nasopharyngeal trauma during nasotracheal intubation in a child with factor IX deficiency having dental restoration. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:1056–1057. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000133914.26066.99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong A, Subar P, Witherell H, Ovodov K. Reducing nasopharyngeal trauma: the urethral catheter-assisted nasotracheal intubation technique. Anes Prog. 2011;58:26–30. doi: 10.2344/0003-3006-58.1.26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kucik CJ, Clenney T. Management of Epistaxis. Vol. 71. American Academy of Family Physicians; 2005. pp. 305–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]