Abstract

Objective:

To investigate partial volume correction (PVC) of 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-Deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography in Alzheimer disease in a longitudinal context.

Methods:

A total of 115 participants were included, including 55 controls, 53 patients with mild cognitive impairment, and 7 patients with dementia of the Alzheimer type. Imaging was performed at baseline and 24 months. Partial volume corrected vs uncorrected rates of longitudinal change were compared for mesial temporal and cortical regions of interest.

Results:

Partial volume correction increased apparent uptake, and this effect was greater at 24 months compared with baseline. Partial volume correction decreased the rate of decline, causing an apparent increase in uptake at 24 months compared with baseline. This effect was correlated with the structural atrophy.

Conclusions:

These findings suggest that applying PVC in a longitudinal context in Alzheimer disease might produce unpredictable results. Accordingly, both PVC corrected and uncorrected data should be reported to ensure that the results are physiologically plausible.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, partial volume effect, partial volume correction, 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-Deoxy-d-glucose

Alzheimer disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative condition and the most common cause of dementia.1 Cerebral metabolism is abnormal in AD secondary to synaptic dysfunction, and positron emission tomography (PET), using the glucose analogue 2-[18F]-fluoro-2-Deoxy-d-glucose (18F-FDG) as the radiotracer, has been used extensively in both research and clinical investigations to image this.2,3 Overall, the pattern of cerebral hypometabolism corresponds to the known distribution of neuropathology in AD, and the magnitude of hypometabolism predicts the severity of the clinical syndrome.4–9 As such, imaging with 18F-FDG–PET reliably distinguishes between patients and controls in cross-sectional studies, with a pooled accuracy typically greater than 90%.10–12

A significant challenge for researchers using PET imaging, including 18F-FDG–PET, is the partial volume effect (PVE). Partial volume effect occurs when signal from a small structure is underestimated because the relatively low resolution of PET data means that a single PET voxel may overlap more than one structure and tissue classes.13 This effect occurs for structures smaller than 2 times the full width at half maximum (FWHM) of the scanner resolution.14In the case of18F-FDG–PET, the result of PVE is to cause an apparent reduction in gray matter metabolic activity in regions where its thickness is less than 2 times the FWHM, and there is overlap from white matter and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) regions that have low activity. Because the signal for CSF is relatively lower than white matter, the attenuation of gray matter signal is greatest for structures that are adjacent to CSF spaces. This renders the issue of PVE of special importance given the prominent atrophy in grey matter (GM) structures in AD.

A number of methods are currently available to potentially correct for the PVE, collectively known as partial volume correction (PVC), and several studies have investigated the effect of PVC in AD.13,15,16 These studies, however, have been cross sectional in design, and to the best of our knowledge, no studies to date have examined the effect of PVC in a longitudinal AD cohort. This is especially important given the increasing use of18F-FDG–PET17 as a biomarker in clinical trials to evaluate potential disease-modifying therapies for AD. For the role of PVC in a longitudinal context, there are several possible scenarios. The first is that PVE is constant across time—that is, it equally affects the measured uptake at all time points. If so, PVE may cancel out over time, and therefore, there is no need for PVC in longitudinal studies as long as only relative change is of interest. In this case, the unnecessary use of PVC may, by virtue of simple data manipulation, introduce noise and reduce power.

The second, and more plausible, possibility is that the effect of PVE is not constant across time. This would be the case if the atrophy between acquisitions means that the amount of required PVC is greater at successive time points (ie, because of the decrease in the size of certain structures and the increase in prominence of CSF spaces). If this is the case, PVE cannot be assumed to cancel out and would need to be corrected for at all time points in longitudinal studies. The third possibility is that the combination of reduced neuronal uptake and atrophy may enhance the sensitivity of FDG-PET for the detection of disease progression and thereby be advantageously aided by the lack of PVC through improved diagnostic sensitivity.

We report the effect of PVC on 18F-FDG–PET uptake in a longitudinal context in elderly controls, patients with mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and patients with dementia of the Alzheimer type (DAT). The main aim was to investigate whether the effect of automated PVC was equal across time points and, as such, could be assumed to cancel out in longitudinal analyses. The second aim was to investigate the relationship between whole-brain structural atrophy and the degree of PVC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Participants

Data used in the preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). The ADNI was launched in 2003 by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, the Food and Drug Administration, private pharmaceutical companies, and nonprofit organizations, as a $60 million, 5-year public-private partnership. The primary goal of ADNI has been to investigate whether serial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), PET, other biological markers, and clinical and neuropsychological assessment can be combined to measure the progression of MCI and early AD. Determination of sensitive and specific markers of very early AD progression is intended to aid researchers and clinicians to develop new treatments and monitor their effectiveness, as well as lessen the time and cost of clinical trials.

The Principal Investigator of this initiative is Michael W. Weiner, MD, VA Medical Center and University of California, San Francisco. The ADNI is the result of efforts of many coinvestigators from a broad range of academic institutions and private corporations, and participants have been recruited from more than 50 sites across the United States and Canada. The initial goal of ADNI was to recruit 800 participants, but ADNI has been followed by ADNI-GO and ADNI-2. To date, these 3 protocols have recruited more than 1500 adults aged 55 to 90 years to participate in the research, consisting of cognitively normal older individuals, people with early or late MCI, and people with early AD. The follow-up duration of each group is specified in the protocols for ADNI-1, ADNI-2, and ADNI-GO. Participants originally recruited for ADNI-1 and ADNI-GO had the option to be followed up in ADNI-2. For up-to-date information, see www.adni-info.org.

For the present study, data were obtained from participants in ADNI-1 who had both T1-structural MRI volumes and 18F-FDG–PET acquisitions acquired approximately 2 years apart (M = 26.30 months, SE = 0.14 between acquisitions). The ADNI database was first accessed and the complete standardized MRI data set was downloaded. This data set is recommended by the ADNI group for use by the research community, as the data have been checked to ensure minimum quality control standards.18 From this data set, those with T1 structural scans at months 12 and 36 were extracted. These time points were chosen essentially arbitrarily, except that they were selected by estimation to result in the maximum number of participants with data separated by 24 months. Participants without corresponding FDG-PET images at each time point were then excluded. This resulted in 115 participants, corresponding to healthy controls (HCs), MCI, and DAT. The clinical characteristics of the ADNI cohort, including diagnostic criteria for each group, are described elsewhere.19 Demographic details of the sample are shown in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Sample Characteristics

| Diagnostic Group |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HC | MCI | DAT | Total | |

| Baseline n (24 months) | 55 (51) | 53 (37) | 7 (27) | 115 |

| % Male | 67 | 76 | 43 | 69 |

| Mean age (SE), y | 75.56 (0.71) | 75.83 (0.94) | 77.57 (2.14) | 75.97 (0.56) |

| Mean MMSE (SE)* | 29.23 (0.14) | 27.09 (0.29) | 24.86 (0.80) | 27.95 (0.20) |

| Mean ADAS-Cog (SE)* | 9.67 (0.67) | 18.55 (0.87) | 24.95 (1.65) | 14.76 (0.70) |

| Mean CDR (SE)* | 0.04 (0.02) | 0.5 | 0.71 (0.10) | 0.30 (0.27) |

Analysis of variance linear contrast significant at P < 0.001.

ADAS-Cog indicates Alzheimer Disease Assessment Scale (Cognitive Subscale); CDR, Clinical Dementia Rating; MMSE, Mini Mental Status Examination.

Image Acquisition

MPRAGE T1 structural volumes were downloaded from the ADNI database in the most preprocessed and quality checked forms available. Full details of the ADNI structural MRI protocol are detailed elsewhere.20 Briefly, images acquired on GE and Siemens systems with transmit-receive head radiofrequency coils underwent gradwarp processing to correct for gradient nonlinearity. Those images acquired on GE and Siemens systems with receive-only head radiofrequency coils underwent additional B1 nonuniformity correction. As per the ADNI protocol, all MRAGE images underwent N3 correction to reduce intensity nonuniformity and were spatially scaled to control for inter scanner variation based on the acquisition of a phantom image acquired immediately after each participant was scanned.

Images on 18F-FDG–PET were downloaded in their most preprocessed form, and full details of acquisition and preprocessing have been published.5 By way of brief description, preprocessing for dynamically acquired images began with coregistering and averaging. As per the ADNI preprocessing pipeline, all images were then reoriented to a standard image matrix with uniform voxel size (1.5 mm cubic) and were then filtered with a scanner-specific function to produce smoothed images with a uniform isotropic resolution of 18-mm FWHM (the approximate resolution of the lowest resolution scanners in the ADNI study).

Partial Volume Correction

Partial volume correction was performed on 18F-FDG–PET images with the PVElab software.21 Briefly, this involves coregistering the T1 MRI volume to the FDG-PET image, then segmenting the T1 into tissue classes (ie, white matter, gray matter, and CSF). This tissue information is then used to correct the 18F-FDG–PET volume for PVE using the method of Müller-Gärtner et al22 to correct GM uptake due to spill-in and spill-out from adjacent non GM structures. White matter uptake was corrected using the method of Rousset et al.14 This procedure is performed in the native space of the 18F-FDG–PET images, and neither the PET nor MPRAGE images are warped to a standard space. Corrected volumes were generated, and data were extracted from regions of interest (ROIs) as described below.

Regions of Interest

A large mesial temporal ROI (MTL) was created using the Harvard-Oxford probabilistic cortical atlas in the FSL software.23 The left and right hippocampus and parahippocampal regions were added to form a single mask, and then smoothed with an 8-mm FWHM kernel and threshold at 90% to eliminate extraneous voxels. For cortical regions, UC Berkeley meta-ROIs were downloaded from the ADNI Web site. These ROIs, extracted from a meta-analysis of 15 18F-FDG–PET studies, comprise the angular gyrus (left and right), superior/middle temporal gyrus (left and right), and the posterior cingulate cortex.24 For this analysis, these 5 ROIs were combined to form a single mean composite cortical ROI. For the purposes of intensity normalization, ROIs were generated for the pons and cerebellar vermis by drawing an 8-mm sphere MNI T1 template. Because all ROIs were specified in MNI space, each was inversely registered to the 18F-FDG–PET volume to avoid unnecessary interpolation, using nonlinear normalization in the SPM8 software (Wellcome Institute of Neurology, UCL). Each registration was checked manually to ensure accurate ROI positioning. Mean uptake were extracted for each ROI using the FSL,23 and the mesial temporal and cortical values were normalized to the uncorrected mean of the pons and cerebellar vermis.

Brain Atrophy

Two-time-point percentage brain volume change was estimated with SIENA,25,26 part of FSL.27 SIENA starts by extracting brain and skull images from the 2-time-point whole-head input data.28 The 2 brain images are then aligned to each other29,30 (using the skull images to constrain the registration scaling); both brain images are resampled into the space halfway between the 2. Next, tissue-type segmentation is carried out31 to find brain/nonbrain edge points, and then perpendicular edge displacement (between the 2 time points) is estimated at these edge points. Finally, the mean edge displacement is converted into a (global) estimate of percentage brain volume change between the 2 time points. This global estimate was then annualized by dividing by the number of years between MRI acquisitions.

Statistical Analyses

All statistical analyses were performed in the SPSS 19.0 software (IBM Corporation). For comparison of paired values (such as corrected vs uncorrected uptake), paired sample t tests were used. For each ROI, the difference between corrected and uncorrected uptake was calculated as the percentage difference between the 2, relative to uncorrected uptake. The annualized rate of change per ROI was calculated as the percentage change relative to baseline. For comparisons made across groups, 1-way analysis of variance models were estimated with a priori linear contrasts. For these analyses, the t tests for the linear contrasts are reported.

All group comparisons were conducted on the baseline diagnostic groups. That is, if participants' diagnostic status was different at 2 years, they were still analyzed in their baseline group.

RESULTS

Group Differences in PVC

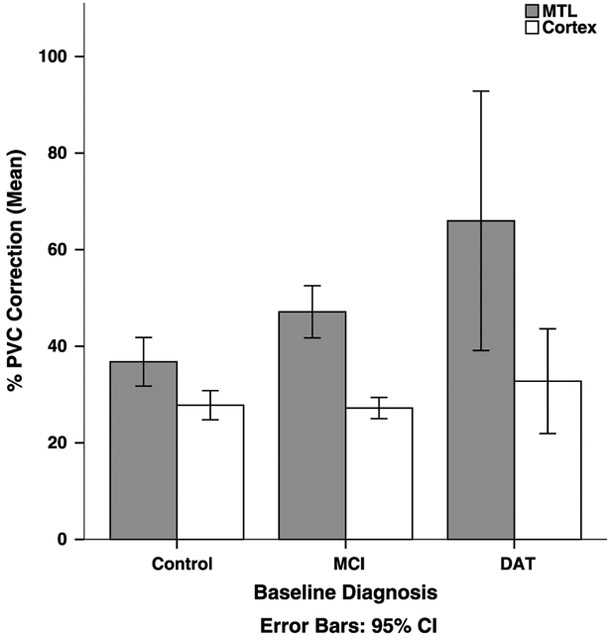

The effect of PVC was significantly greater than zero for all regions across all diagnostics groups (all comparisons, P <0.001). Figure 1 shows the effect of PVC by region and baseline diagnostic group. Overall, the mean effect of PVC was significantly greater for the MTL compared with cortex (t114 = 8.64, P < 0.001). The effect of PVC varied significantly between diagnostic groups for the mesial temporal region (t114 = 3.68, P < 0.001), with a mean PVC effect in the DAT group of 65.97% (SE = 10.97), 47.13% (SE = 2.69) in the MCI group, and 36.78% (SE = 2.51) in the HC group. This group effect was not significant for the cortex (P = 0.37).

FIGURE 1.

Effect of PVC for the MTL and cortex, across diagnostic groups at baseline. Partial volume correction increased uptake for all regions and across all diagnostic groups (P <0.001). The effect of PVC on the MTL was greater in the DAT group compared with the MCI group, which was greater than the control group (P < 0.001). The linear trend was not significant for the cortex (P = 0.37). This analysis was conducted on the HC (n = 55), MCI (n = 53), and DAT (n = 7) groups.

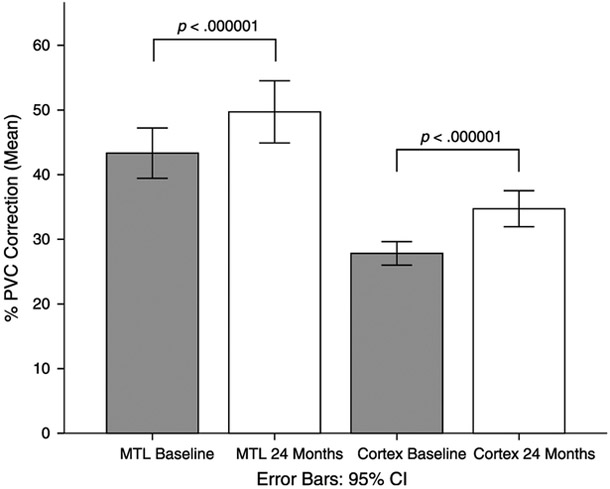

Effect of PVC at Different Time Points

As shown in Figure 2, the effect of PVC was significantly greater at 24 months, compared with baseline, for both the MTL and the cortex. For the MTL, PVC increased uptake by 43.33% (SE = 1.96) at baseline, compared with 49.71% (SE = 2.43) at 24 months (t114 = 5.76, P < 0.001). For the cortex, PVC increased uptake by 27.82% (SE = 0.92) at baseline, compared with 34.74% (SE = 1.40) at 24 months (t114 = 5.95, P < 0.001). The effect of this increase in PVC was not significantly different between the MTL and cortex (t114 = 0.30, P = 0.76).

FIGURE 2.

Effect of PVC correction across ROIs for baseline and 24 months. The effect of PVC was greater at 24 months compared with baseline for both regions (P < 0.001). All participants were included in this analyses (n = 115).

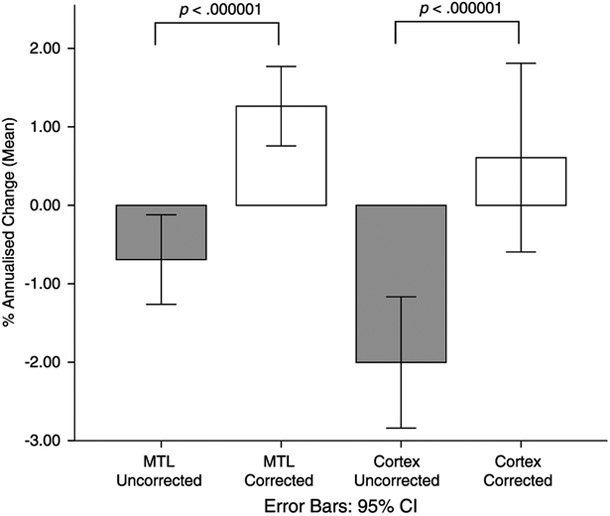

Effect of PVC on Longitudinal Change

Before PVC, the mean annualized rate of change was −0.69% (SE = 0.29) for the MTL and −2.00% (SE = 0.42) for the cortex. These rates of change were significantly different from zero for both the MTL (t114 = −2.40, P = 0.01) and the cortex (t114 = −4.74, P < 0.001). The effect of PVC on annualized rates of change was statistically significant for the MTL (t114 = −5.46, P < 0.001) and the cortex (t114 = −6.04, P < 0.001). Specifically, after PVC, the mean annualized change for the MTL, at 1.26% (SE = 0.26), was significantly greater than zero (t114 = 4.95, P <0.001). In contrast, the mean annualized change for the cortex was no longer significantly different from zero (t114 = 1.00, P = 0.32). These results are shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Annualized change in uptake by region and correction status. For the MTL, the effect of PVC was to increase the rate of annual change such that uptake increased over time (P < 0.001). The effect of PVC on cortical annualized change was to render the rate of change no longer significantly different from zero. All participants were included in this analyses (n = 115).

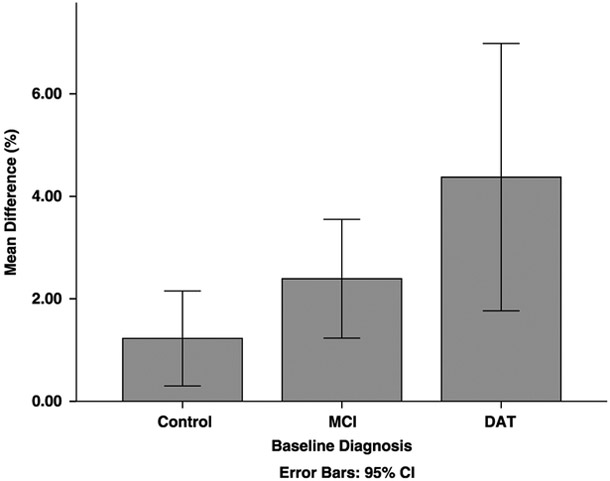

As shown in Figure 4, the mean percentage difference between uncorrected and corrected annualized change varied across diagnostic groups for the MTL. A planned linear contrast was statistically significant (t114 = 2.48, P = 0.02), indicating that the increase in annual change was greatest for the DAT group (M = 4.37%, SE = 1.07), followed by the MCI (M = 2.39%, SE = 0.58) and HC (M = 1.23%, SE = 0.46) groups. In contrast, there was no overall group difference for the cortex (F2,114 = 0.87, P = 0.42.

FIGURE 4.

The difference between corrected and uncorrected annualized MTL change was greater in the DAT group compared with the MCI group, which was greater than the control group (P < 0.02).

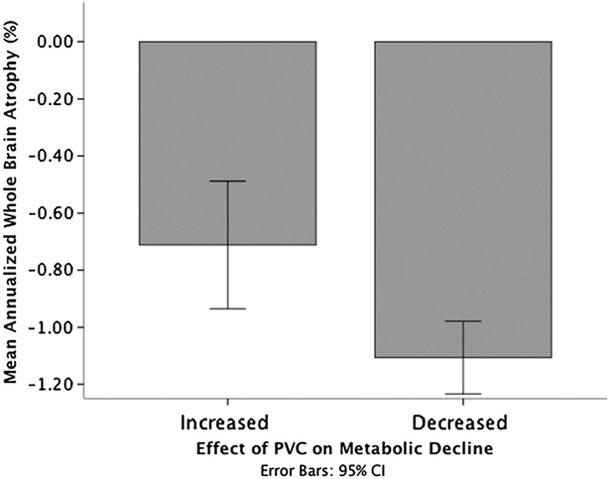

Relationship Between PVC Effect and Cerebral Atrophy

Whole-brain atrophy varied between baseline diagnostic group, with a significant linear trend (t112 = −3.52, P = 0.001), indicating that atrophy was greatest for the DAT group and lowest for the HCs. Whole-brain atrophy was negatively related to effect of PVC on annualized change for the MTL (r = −0.39, P <0.001), but not the cortical regions (r = −0.05, P = 0.56). Greater brain atrophy was associated with a greater reduction in apparent metabolic decline. For illustrative purposes, participants were divided into those where PVC reduced their apparent metabolic decline and those where PVC increased their apparent decline. As shown in Figure 5, whole-brain atrophy was greater in those where PVC reduced their apparent decline (t112 = 3.19, P = 0.002).

FIGURE 5.

Greater atrophy was observed in cases where PVC decreased the rate of metabolic decline, compared with cases where PVC increased the rate of metabolic decline.

DISCUSSION

As expected, the effect of PVC on cross-sectional data was to increase the apparent cerebral metabolism. This finding agrees with previous studies and is consistent with the aim of PVC to increase apparent GM uptake.15,16 We also found that the greater correction was required in the MTL, compared with cortical regions. Again, this was consistent with our expectations as MTL GM regions consist of relatively small structures adjacent to large CSF spaces with lower apparent uptake.

As expected, we also demonstrated that for the MTL region, the effect of PVC varied by diagnostic group. Specifically, the DAT group required the greatest amount of correction compared with the MCI and then compared with the HC group. The most likely explanation of this effect is that the atrophy was greatest in the DAT group, with the least atrophy in the healthy group. As such, MTL structures prone to atrophy in AD (such as the hippocampus) are smaller in volume, and the effect of CSF (with inherently lower uptake) is greater. The amount of correction in the MCI group (less than the DAT group but greater than the control group) supports this notion, and the overall atrophy burden in the MCI group is likely to sit between the DAT and control groups.

For longitudinal change, we found that the amount of PVC was greater at subsequent time points. At first glance, this finding seems to support the view that PVE cannot be assumed to cancel out across time, and that PVC needs to be addressed at each time point in a longitudinal design. On closer examination, we paradoxically found that the effect of PVC was to decrease the rate of apparent metabolic decline. For the MTL, this resulted in an increase in apparent metabolism over time, rather than the decrease that is usually associated with the progressive pathological processes of AD. The effect on cortical regions was to essentially nullify the change over time, such that no statistically significant change was observed. The most likely cause of this effect is overcorrection due to brain atrophy occurring over time, and this view is supported by the relationship between whole-brain atrophy and magnitude of PVC effect. Specifically, the greater the decrease in GM volume, the more the PVC procedure increased the apparent uptake in this region. Given the bordering CSF spaces in this region, this effect is likely more pronounced than in the cortex, and this may explain why this same effect was not observed in the cortical regions.

Unlike previous studies that have investigated PVC in AD using cross-sectional designs, our study is the first to our knowledge that has examined this issue in a longitudinal context. This is a key strength of this study, as the PVC method we used seems valid in a cross-sectional analysis, and it is only in a longitudinal context that the issue of overcorrection declares itself. There are a number of limitations to this study, including the fact that the data were collected across multiple sites, with differences in the way the data were acquired. The relatively large smoothing kernel applied to the PET images (18 mm) is also a potential issue as this may have affected the result of PVC. We attempted to correct for this by employing a large MTL ROI, and the cortical ROIs have been used on these data previously with coherent results. The DAT group was relatively small (n = 7) at baseline. Although this was taken into account statistically, the inclusion of a larger DAT cohort may be beneficial in future studies. As such, a clear next step will be to replicate this finding in a separate data set and extend it to other PVC approaches.

Partial volume correction was performed in this study using a combined method implemented in freely available software. We believe that this represents the approach taken by many researchers who may wish to perform PVC and use existing software pipelines, rather than developing their own methods. As such, our findings do not suggest that all PVC methods will necessarily result in the same longitudinal outcome. They do, however, caution researchers not to apply PVC correction without comparing the results with uncorrected data. As such, a clear next step will be to replicate this finding in a separate data set and extend it to other PVC approaches.

Overall, we have demonstrated significant issues in the application of PVC to 18F-FDG–PET images acquired longitudinally in patients with AD. Our findings suggest that PVC is sensitive to atrophy in longitudinal contexts and might overcorrect for the effect that this has on apparent PET intensity in AD. This a particular concern given the increasing use of 18F-FDG–PET as a biomarker of potential disease-modifying treatment studies of AD, where this overcorrection could potentially nullify a true difference in metabolic change between treatment arms and decrease the sensitivity for detection of progressive disease. As such, the prudent approach in such studies would be to analyze and report both PVC corrected and uncorrected data to ensure that the results are meaningful and physiologically plausible.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Charles Malpas is the recipient of an Alzheimer Australia Dementia Research Foundation Viertel postgraduate research scholarship.

Data collection and sharing for this project was funded by the ADNI (National Institutes of Health Grant U01 AG024904) and Department of Defense ADNI (Department of Defense Award No. W81XWH-12-2-0012). The ADNI is funded by the National Institute on Aging, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, and through generous contributions from the following: Alzheimer Association; Alzheimer Drug Discovery Foundation; Araclon Biotech; Bio Clinica, Inc; Biogen Idec Inc; Bristol-Myers Squibb Company; Eisai Inc; Elan Pharmaceuticals, Inc; Eli Lilly and Company; Euro Immun; F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and its affiliated company Genentech, Inc; Fujirebio; GE Healthcare; IXICO Ltd.; Janssen Alzheimer Immunotherapy Research and Development, LLC.; Johnson and Johnson Pharmaceutical Research and Development LLC.; Medpace, Inc; Merck and Co, Inc; Meso Scale Diagnostics, LLC.; NeuroRx Research; Neurotrack Technologies; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Pfizer Inc; Piramal Imaging; Servier; Synarc Inc; and Takeda Pharmaceutical Company. The Canadian Institutes of Health Research is providing funds to support ADNI clinical sites in Canada. Private sector contributions are facilitated by the Foundation for the National Institutes of Health (www.fnih.org). The grantee organization is the California Institute for Research and Education, and the study is coordinated by the Alzheimer's Disease Cooperative Study at the University of California, San Diego. ADNI data are disseminated by the Laboratory for Neuro Imaging at the University of Southern California.

Footnotes

Data used in preparation of this article were obtained from the Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) database (adni.loni.usc.edu). As such, the investigators within the ADNI contributed to the design and implementation of ADNI and/or provided data but did not participate in analysis or writing of this report. A complete listing of ADNI investigators can be found at: http://adni.loni.usc.edu/wp-content/uploads/how_to_apply/ADNI_Acknowledgement_List.pdf.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hodges JR. Alzheimer's centennial legacy: origins, landmarks and the current status of knowledge concerning cognitive aspects. Brain. 2006;129:2811–2822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nordberg A, Rinne JO, Kadir A, et al. The use of PET in Alzheimer disease. Nat Rev Neurol. 2010;6:78–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reiman EM, Jagust WJ. Brain imaging in the study of Alzheimer's disease. Neuroimage. 2012;61:505–516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arlt S, Brassen S, Jahn H, et al. Association between FDG uptake, CSF biomarkers and cognitive performance in patients with probable Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Nucl Med Molec Imaging. 2009;36:1090–1100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jagust WJ, Bandy D, Chen K, et al. The Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative positron emission tomography core. Alzheimers Dement. 2010;6:221–229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walhovd KB, Fjell AM, Dale AM, et al. Multi-modal imaging predicts memory performance in normal aging and cognitive decline. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:1107–1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schönknecht ODPO, Hunt AA, Toro PP, et al. Bihemispheric cerebral FDG PET correlates of cognitive dysfunction as assessed by the CERAD in Alzheimer's disease. Clin EEG Neurosci. 2011;42:71–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Foster NL, Heidebrink JL, Clark CM, et al. FDG-PET improves accuracy in distinguishing frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer's disease. Brain. 2007;130(pt 10): 2616–2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jagust W, Reed B, Mungas D, et al. What does fluorodeoxyglucose PET imaging add to a clinical diagnosis of dementia? Neurology. 2007;69:871–877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen W-P, Samuraki M, Yanase D, et al. Effect of sample size for normal database on diagnostic performance of brain FDG PET for the detection of Alzheimer's disease using automated image analysis. Nucl Med Commun. 2008;29:270–276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bohnen NIN, Djang DSW, Herholz KK, et al. Effectiveness and safety of 18F-FDG PET in the evaluation of dementia: a review of the recent literature. J Nucl Med. 2012;53:59–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mosconi L, Tsui WH, Herholz K, et al. Multicenter standardized 18F-FDG PET diagnosis of mild cognitive impairment, Alzheimer's disease, and other dementias. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:390–398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thomas BAB, Erlandsson KK, Modat MM, et al. The importance of appropriate partial volume correction for PET quantification in Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Nucl Med Molec Imaging. 2011;38:1104–1119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rousset OGO, Ma YY, Evans ACA. Correction for partial volume effects in PET: principle and validation. J Nucl Med. 1998;39:904–911. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mevel K, Desgranges B, Baron J-C, et al. Detecting hippocampal hypometabolism in mild cognitive impairment using automatic voxel-based approaches. Neuroimage. 2007;37:8–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meltzer CC, Zubieta JK, Brandt J, et al. Regional hypometabolism in Alzheimer's disease as measured by positron emission tomography after correction for effects of partial volume averaging. Neurology. 1996;47: 454–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Foster NLN, Wang AYA, Tasdizen TT, et al. Realizing the potential of positron emission tomography with 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose to improve the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement.2008;4(1 suppl 1):0–0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wyman BT, Harvey DJ, Crawford K, et al. Standardization of analysis sets for reporting results from ADNI MRI data. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9:332–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Petersen RC, Aisen PS, Beckett LA, et al. Alzheimer's Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI): clinical characterization. Neurology. 2010;74:201–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jack CR, Bernstein MA, Fox NC, et al. The Alzheimer's disease neuroimaging initiative (ADNI): MRI methods. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2008;27:685–691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quarantelli MM, Berkouk KK, Prinster AA, et al. Integrated software for the analysis of brain PET/SPECT studies with partial-volume-effect correction. J Nucl Med. 2004;45:192–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Müller-Gärtner HW, Links JM, Prince JL, et al. Measurement of radiotracer concentration in brain gray matter using positron emission tomography: MRI-based correction for partial volume effects. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 1992;12:571–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jenkinson M, Beckmann C, Behrens T, et al. FSL. Neuroimage. 2012;62:782–790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Landau SM, Harvey D, Madison CM, et al. Comparing predictors of conversion and decline in mild cognitive impairment. Neurology. 2010;75:230–238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith SM, De Stefano N, Jenkinson M, et al. Normalised accurate measurement of longitudinal brain change. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001;25:466–475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Smith S, Zhang Y, Jenkinson M, et al. Accurate, robust and automated longitudinal and cross-sectional brain change analysis. Neuroimage. 2002;17:479–489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith S, Jenkinson M, Woolrich M, et al. Advances in functional and structural MR image analysis and implementation as FSL. Neuroimage. 2004;23(S1):208–219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith SM. Fast robust automated brain extraction. Hum Brain Mapp. 2002;17:143–155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jenkinson M, Smith S. A global optimisation method for robust affine registration of brain images. Med Image Anal. 2001;5:143–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jenkinson M, Bannister P, Brady J, et al. Improved optimisation for the robust and accurate linear registration and motion correction of brain images. Neuroimage. 2002;17:825–841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang Y, Brady M, Smith S. Segmentation of brain MR images through a hidden Markov random field model and the expectation maximization algorithm. IEEE Trans Med Imaging. 2001;20:45–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]