Abstract

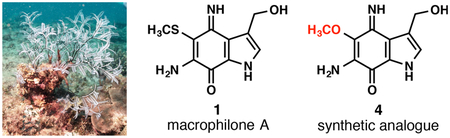

A previously uncharacterized pyrroloiminoquinone natural product, macrophilone A, was isolated from the stinging hydroid Macrorhynchia philippina. The structure was assigned utilizing long-range NMR couplings and DFT calculations and proved by a concise, five-step total synthesis. Macrophilone A and a synthetic analogue displayed potent biological activity, including increased intracellular reactive oxygen species levels and submicromolar cytotoxicity toward lung adenocarcinoma cells.

Graphical Abstract

Nature has proven to be a source of countless unique chemical structures with diverse biological activities, often serving as the inspiration for clinical drugs.1 Colonial marine invertebrates, such as sponges, soft corals, and ascidians, have provided a wide variety of potent, biologically active small molecules.2 Two such small molecules, eribulin3,4 and trabectedin,5 have recently been translated into clinically approved anticancer agents. In contrast, hydroids are widely distributed in the world’s oceans but have rarely been examined chemically, in part due to difficulty of collection. The hydroid Macrorhynchia philippina, also known as the stinging hydroid or white stinger, grows readily in many oceanic habitats and is often viewed as an invasive species. Despite its widespread occurrence, there have been no previous reports in the chemical literature describing metabolites from this organism.

The organic solvent extract of M. philippina was originally selected for chemical investigation due to its cytotoxicity profile in the NCI-60 cell line anticancer screen.6,7 As part of these initial investigations, the extract was also tested in a variety of molecularly targeted assays, including the small ubiquitin-like modifier (SUMO) conjugation cascade.8 Covalent attachment of the SUMO protein is a post-translational modification critical for the regulation of various cellular processes and is often disrupted in diseases, including cancer.9–16 SUMO conjugation to protein substrates occurs through an enzymatic E1 (Aos1/Uba2 heterodimer), E2 (Ubc9), and E3 (various ligases) cascade. Efforts to develop a synthetic inhibitor of protein sumoylation have proven highly challenging. Several metabolites have been identified from terrestrial plant and bacterial sources that inhibit sumoylation,17–20 including the o-quinones nocardione A and β-lapachone21 and the p-quinone kerriamycin B.22 A novel iminoquinone derived from the hydroid M. philippina that arrests the SUMO conjugation cascade by an oxidative mechanism of action was identified. The isolation, structural elucidation, total synthesis, and biological evaluation of this marine natural product, macrophilone A, are reported herein.

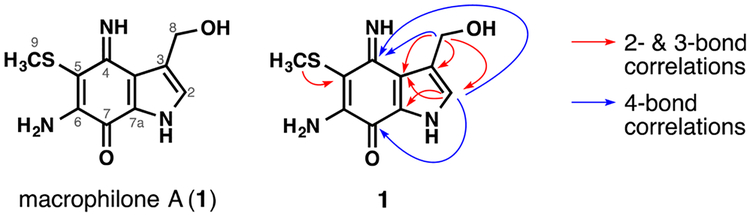

Sequential chromatographic fractionation of the hydroid extract on diol, Sephadex LH-20, and C18 solid supports provided macrophilone A (1) (Figure 1), which had a heteroatom-rich molecular formula of C10H11N3O2S by HRESIMS that required seven degrees of unsaturation. UV absorptions at 213, 259, 325, and 390 nm suggested an extended aromatic chromophore similar to the pyrroloiminoquinone secobatzelline A.23 The 1H NMR spectrum showed signals indicative of an olefinic proton (δH 7.29 s, H−2), an oxymethylene (δH 4.74 s, H2−8), and a methylthio group (δH 2.21 s, H3−9) (Table 1, CD3OD). The 13C NMR spectrum revealed seven quaternary sp2 carbons [δC 169.6 (C-7), 163.7 (C-4), 156.4 (C-6), 130.4 (C-7a), 127.2 (C-3a), 123.0 (C-3), and 95.7 (C-5)] and one sp2 methine (δC 128.2, C-2), which are characteristic of a substituted pyrroloiminoquinone skeleton,23 as well as oxymethylene (δC 57.1, C-8), and methylthio (δC 17.1, C-9) carbons.

Figure 1.

Macrophilone A (1) and key 1H−13C HMBC correlations.

Table 1.

13C NMR Chemical Shift Data for Isolated and Synthetic Macrophilone A and DFT-Calculated Chemical Shifts

| position | natural product | synthetic | calculated | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DMSO-d6 | CD3OD | CD3OD | CD3OD | gas phase | ||||

| 1H | 13C | 1H | 13C | 1H | 13C | 13C | 13C | |

| 2 | 7.21 | 125.5 | 7.29 | 128.2 | 7.29 | 128.4 | 124.9 | 121.8 |

| 3 | 126.2 | 123.0 | 122.5 | 128.5 | 132.1 | |||

| 3a | 126.9 | 127.2 | 127.2 | 129.3 | 130.2 | |||

| 4 | 160.8 | 163.7 | 163.8 | 162.3 | 161.6 | |||

| 5 | 101.0 | 95.7 | 95.2 | 102.6 | 103.5 | |||

| 6 | 147.8 | 156.4 | 156.9 | 148.3 | 147.6 | |||

| 7 | 170.0 | 169.6 | 169.5 | 169.5 | 169.0 | |||

| 7a | 128.1 | 130.4 | 130.5 | 127.1 | 127.2 | |||

| 8 | 4.52 | 56.1 | 4.74 | 57.1 | 4.74 | 57.1 | 55.6 | 56.6 |

| 9 | 2.08 | 16.7 | 2.21 | 17.1 | 2.21 | 17.1 | 18.7 | 19.1 |

HMBC correlations (Figure 1) from H2−8 to C-2/C-3/C-3a and from H−2 to C-7a established a 3-hydroxymethyl pyrrole ring. Four-bond HMBC correlations from H−2 to C-7/C-4 extended the substructure to incorporate the carbonyl and imino centers consistent with a substituted iminoquinone moiety. An HMBC correlation for H3−9 to C-5 established the position of the methylthio group. The exchangeable NH protons were never observed regardless of the deuterated solvent used, but key four-bond HMBC correlations, in combination with diagnostic chemical shift values, allowed us to assign the regiochemistry of the ring system. An HMBC correlation from H2−8 to C-4 revealed the fusion pattern between the pyrrole and iminoquinone rings in 1 was the same as in secobatzelline A.23 The shielded chemical shift of C-5 (δC 95.7) relative to C-6 (δC 156.4) suggested the S and N atoms were substituted at positions 5 and 6, respectively. A long-range HMBC experiment optimized for 2 Hz 1H−13C couplings showed four-bond correlations from the methylthio protons to the imino (C-4) and amino-bearing (C-6) carbons as well as a weak 5-bond correlation to the bridgehead carbon (C-3a), which established that the methylthio group was attached to C-5. Thus, macrophilone A (1) was assigned as 6-amino-3-(hydroxymethyl)-4-imino-5-(methylthio)-1,4-dihydro-7H-indol-7-one (Figure 1).

To further validate the proposed structure, DFT calculations were performed using gauge-including atomic orbitals (GIAO) at the mPW1PW91/6–311+G(2d,p) level both in the gas phase and in methanol solvent to predict the carbon chemical shifts of four possible geometric isomers (Table 1 and Figure S1).24 DFT calculations can capture subtleties in the molecular environment due to changes in the overall π-system of the iminoquinone that are not accessible to the substructure-based increment methods implemented in lower levels of computational theory. The DFT chemical shift predictions for carbon atoms C-4, C-5, C-6, and C-7 were calculated, and the errors of prediction of these four atoms across the four isomers were plotted (Figure S1). Comparison of the isomers revealed that DFT values calculated for structure 1 most closely matched the 13C chemical shifts observed with the naturally occurring macrophilone A.

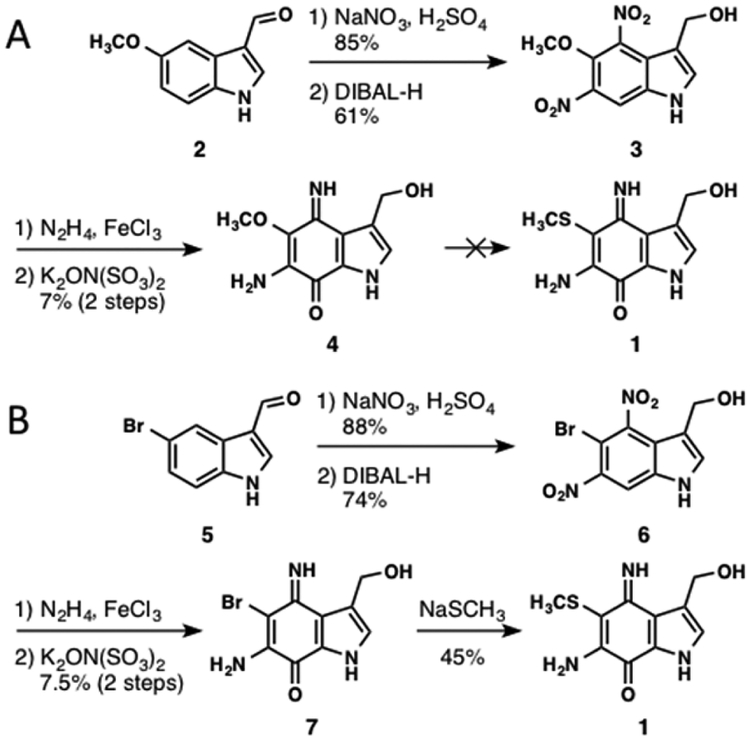

To provide unambiguous proof for the structure and to generate additional material for biological evaluation, the total synthesis of 1 was pursued. The synthesis began with indole 2, which was readily nitrated under standard conditions in 85% yield. The aldehyde functionality was reduced with DIBAL-H to afford 3 in 61% yield (Scheme 1A). Treatment with FeCl3/N2H4 resulted in smooth reduction of the dinitroindole 3.25 Oxidation of this reduced intermediate with potassium nitrosodisulfonate (Fremy’s salt)26 afforded iminoquinone 4 in 7% yield over two steps. Repeated attempts to improve the yield of this transformation using other oxidants or buffer conditions were not met with success, possibly due to the sensitive nature of the substrate and multiple sites of potential oxidative events. Although nucleophilic displacement of methoxy substituents in iminoquinone systems is well-precedented,27 attempted reaction of 4 with sodium methanethiolate was unsuccessful.

Scheme 1.

(A) Initial Strategy for the Synthesis of 1. (B) Total Synthesis of 1

To circumvent the resistance of 4 to sulfhydryl substitution, an alternate synthetic route was designed beginning with bromoindole 5, which was subjected to analogous conditions to yield 7 (Scheme 1B). Generation of 7 occurred in low yield and was again resistant to optimization. Exposure to sodium methanethiolate in methanol transformed this intermediate into compound 1 in 45% yield. The 1H and 13C NMR spectra of synthetic product 1 and the natural product macrophilone A were in good agreement. When equimolar samples of isolated and synthetic 1 were coinjected on HPLC they eluted as a single, symmetrical peak (Figure S2). Additionally, the 13C NMR spectrum of an equimolar mixture of synthetic 1 and natural macrophilone A provided a single set of discrete resonances, confirming the identical nature of these materials.

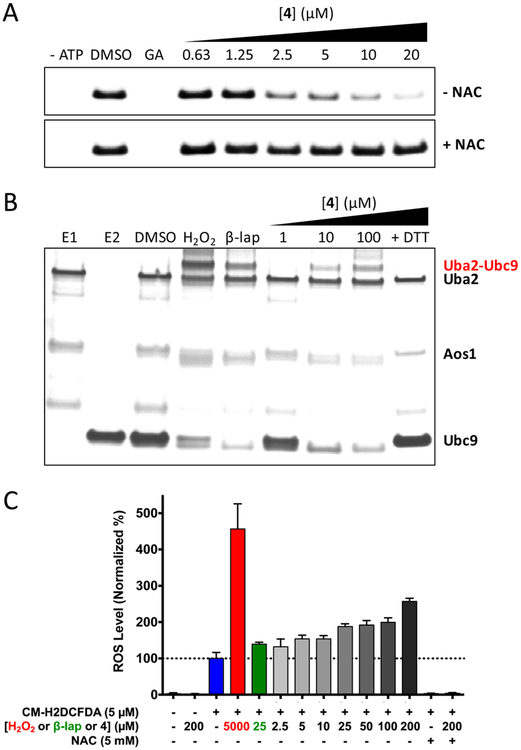

Macrophilone A, like several previously reported quinone-containing compounds, was found to act as an inhibitor of SUMO conjugation.21 A microfluidic electrophoretic mobility shift assay was utilized to measure the ability of 1 and methoxy analogue 4 to inhibit sumoylation of a fluorescently tagged model substrate peptide.8,28 Macrophilone A (1) exhibited an IC50 of 8.0 μM, while synthetic analogue 4 was more potent with an IC50 of 2.5 μM (Figure S3). Quinones and related redox active molecules can generate reactive oxygen species (ROS), an imbalance of which causes oxidative stress in cells that results in damage to proteins, lipids, and DNA.29 Both compounds were subsequently evaluated in the sumoylation assay with the addition of the antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC). NAC abolished the inhibitory activities of 1 and 4, indicating both compounds prevent sumoylation via an oxidative mechanism (Figure 2A and Figure S4).

Figure 2.

(A) Conjugation of SUMO to a fluorescent substrate peptide is inhibited by macrophilone analogue 4. The inhibitory activity of 4 is abolished by addition of the antioxidant NAC to the assay mixture. GA = ginkgolic acid, 30 μM (positive control). (B) Silver stained gel indicating analogue 4 induces E1−E2 cross-linking by formation of a disulfide bond between the E1 subunit Uba2 and the E2 enzyme Ubc9. This cross-linking does not occur with 100 μM 4 in the presence of 100 mM DTT. Both 1 mM H2O2 and 10 μM β-lapachone are included as positive controls. (C) Detection of ROS in A549 cells by fluorescence of CM-H2DCFDA.

Thiol cross-linking of Uba2-Ubc9 has been shown to be the mechanism of inhibition of sumoylation by hydrogen peroxide30 as well as nocardione A and β-lapachone.21 Similarly, compound 4 induced cross-linking of the SUMO E1 and E2 enzymes, characterized by the dose-dependent appearance of a DTT-sensitive high molecular weight band (Figure 2B). Thus, 4 inhibits SUMO conjugation in biochemical assays by an oxidative mechanism that cross-links thiols of the E1 subunit Uba2 and the E2 enzyme Ubc9 via a disulfide bond.

ROS can induce the oxidation of cysteine sulfhydryl (RSH) side chains into sulfenic acids (RSOH), which further react to form disulfide bonds.31 The sulfenic acid probe DCP-Bio1 has been used previously to covalently trap sulfenic acids in the context of whole proteomes.32–34 DCP-Bio1 was used to evaluate changes in RSOH levels of the proteome upon treatment with 4. After incubation of A549 lung adenocarcinoma cells with 4, cells were lysed in the presence of DCP-Bio1, and global protein oxidation was probed (Figure S5). Several new bands were noted upon treatment, and others increased in intensity in a dose-dependent fashion, reflecting a higher level of RSOH proteome-wide and indicating that 4 causes global oxidative damage.

In addition to raising RSOH levels, compound 4 was potently cytotoxic to A549 cells, causing cell death with an EC50 of 145 nM (Figures S6 and S7). To determine if the cytotoxicity was associated with oxidative stress, the fluorogenic dye 5–(6)-chloromethyl-2′,7′-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (CMH2DCFDA) was utilized to measure intracellular ROS levels. Upon co-incubation of A549 cells with CM-H2DCFDA and compound 4, intracellular fluorescence, and thus ROS levels, increased in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2C). These results further suggest that 4 causes an imbalance in the cellular ROS/antioxidant ratio, leading to oxidative stress. Treating cells with 4 while supplementing with the antioxidant NAC did not cause an increase in intracellular ROS levels, yet cell death still occurred (EC50 = 199 nM with NAC). A more membrane-permeable analogue of NAC, N-acetyl-L-cysteine amide,35 failed to mitigate cytotoxicity as well (EC50 = 153 nM) (Figure S6). Taken together, these results indicate that 4, in addition to possessing an oxidative mechanism of action by the generation of ROS, likely exhibits polypharmacology. Further studies to investigate the potent biological activity of 1 and 4 are required.

The structural elucidation, total synthesis, and biological evaluation of macrophilone A (1), a novel iminoquinone isolated from the marine hydroid Macrorhynchia philippina, have been reported. Hydroids are an understudied group of marine invertebrates, and there are no prior reports of compounds from any species in the genus Macrorhynchia. NMR experiments optimized to observe two-, three-, and four-bond 1H−13C couplings were utilized along with DFT-based 13C chemical shift calculations to assign a structure for the natural product. A total synthesis of 1, which proceeded in five linear steps without the use of protecting groups, was developed to unequivocally prove the structure. Macrophilone A and analogue 4 arrest the SUMO conjugation cascade by the generation of ROS, and 4 was observed to induce oxidative cross-linking of Ubc9 and Uba2. Compound 4 also increased levels of oxidized proteins and intracellular ROS as well as displayed submicromolar toxicity in A549 cells. Although the ROS levels in cells were reduced with the addition of the antioxidant NAC, compound 4 remained potently cytotoxic. Macrophilone A and related analogues therefore possess complex mechanisms of action. Further investigations into the chemical constituents of M. philippina and their biological properties appear to be warranted.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Grateful acknowledgement goes to the Natural Products Support Group (NCI at Frederick) for extraction, E. Smith and A. Wamiru for SUMO assay support, and S. Tarasov and M. Dyba (Biophysics Resource, SBL, NCI at Frederick) for assistance with HRMS studies. Quantum mechanics calculations utilized computational resources of the NIH HPC Biowulf cluster (http://hpc.nih.gov). This work was supported in part by grants from the NSFC (No. 21202123), ZJNSFC (No. LQ12B02002), CSC (No. 201408330121), and start-up funding from Wenzhou Medical University (No. QTJ10018). This research was also supported in part by the Intramural Research Program of the NIH, National Cancer Institute, Center for Cancer Research, and with federal funds from the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, under contract HHSN261200800001E and grants 1ZIABC01156803 and 1ZIABC01144905.

Footnotes

Supporting Information

The Supporting Information is available free of charge on the ACS Publications website at DOI: 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b00496.

Experimental procedures, additional figures, and full spectroscopic data for all new compounds (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Newman DJ; Cragg GM J. Nat. Prod 2016, 79, 629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Blunt JW; Copp BR; Keyzers RA; Munro MHG; Prinsep MR Nat. Prod. Rep 2016, 33, 382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Cigler T; Jain S Biol. Targets Ther 2012, 6, 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Doherty MK; Morris PG Int. J. Women’s Health 2015, 7, 47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Demetri GD; von Mehren M; Jones RL; Hensley ML; Schuetze SM; Staddon A; Milhem M; Elias A; Ganjoo K; Tawbi H; Van Tine BA; Spira A; Dean A; Khokhar NZ; Park YC; Knoblauch RE; Parekh TV; Maki RG; Patel SR J. Clin. Oncol 2016, 34, 786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Shoemaker RH Nat. Rev. Cancer 2006, 6, 813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Malhotra SV; Kumar V; Velez C; Zayas B MedChemComm 2014, 5, 1404. [Google Scholar]

- (8).Kim YS; Nagy K; Keyser S; Schneekloth JS Chem. Biol 2013, 20, 604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).McDoniels-Silvers AL; Nimri CF; Stoner GD; Lubet RA; You M Clin. Cancer Res 2002, 8, 1127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Johnson ES Annu. Rev. Biochem 2004, 73, 355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Mo YY; Yu YN; Theodosiou E; Rachel Ee PLR; Beck WT Oncogene 2005, 24, 2677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Mo YY; Moschos SJ Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2005, 9, 1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Zhao J Cell. Mol. Life Sci 2007, 64, 3017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Geiss-Friedlander R; Melchior F Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 2007, 8, 947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Hannoun Z; Greenhough S; Jaffray E; Hay RT; Hay DC Toxicology 2010, 278, 288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Lee YJ; Mou Y; Maric D; Klimanis D; Auh S; Hallenbeck JM PLoS One 2011, 6, e25852. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Fukuda I; Ito A; Hirai G; Nishimura S; Kawasaki H; Saitoh H; Kimura K; Sodeoka M; Yoshida M Chem. Biol 2009, 16, 133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Hirohama M; Kumar A; Fukuda I; Matsuoka S; Igarashi Y; Saitoh H; Takagi M; Shin-ya K; Honda K; Kondoh Y; Saito T; Nakao Y; Osada H; Zhang KYJ; Yoshida M; Ito A ACS Chem. Biol 2013, 8, 2635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Suzawa M; Miranda DA; Ramos KA; Ang KK; Faivre EJ; Wilson CG; Caboni L; Arkin MR; Kim YS; Fletterick RJ; Diaz A; Schneekloth JS; Ingraham HA eLife 2015, DOI: 10.7554/eLife.09003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Takemoto M; Kawamura Y; Hirohama M; Yamaguchi Y; Handa H; Saitoh H; Nakao Y; Kawada M; Khalid K; Koshino H; Kimura K; Ito A; Yoshida MJ Antibiot 2014, 67, 335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Fukuda I; Hirohama M; Ito A; Tariq M; Igarashi Y; Saitoh H; Yoshida MJ Antibiot 2016, 69, 776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Fukuda I; Ito A; Uramoto M; Saitoh H; Kawasaki H; Osada H; Yoshida MJ Antibiot 2009, 62, 221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Gunasekera SP; McCarthy PJ; Longley RE; Pomponi SA; Wright AE J. Nat. Prod 1999, 62, 1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Tantillo DJ Nat. Prod. Rep 2013, 30, 1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Guan Q; Han CM; Zuo DY; Zhai MA; Li ZQ; Zhang Q; Zhai YP; Jiang XW; Bao K; Wu YL; Zhang WG Eur. J. Med. Chem 2014, 87, 306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).LaBarbera DV; Skibo EB J. Org. Chem 2013, 78, 11887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Nijampatnam B; Nadkarni DH; Wu H; Velu SE Microorganisms 2014, 2, 128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Leyva MJ; Kim YS; Peach ML; Schneekloth JS Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett 2015, 25, 2146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Bolton JL; Trush MA; Penning TM; Dryhurst G; Monks TJ Chem. Res. Toxicol 2000, 13, 135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Bossis G; Melchior F Mol. Cell 2006, 21, 349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Pan J; Carroll KS Biopolymers 2014, 101, 165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Poole LB; Klomsiri C; Knaggs SA; Furdui CM; Nelson KJ; Thomas MJ; Fetrow JS; Daniel LW; King SB Bioconjugate Chem 2007, 18, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Klomsiri C; Nelson KJ; Bechtold E; Soito L; Johnson LC; Lowther WT; Ryu SE; King SB; Furdui CM; Poole LB In Methods in Enzymology; Cadenas E, Packer L, Eds.; Elsevier Academic Press, Inc.: San Diego, 2010; Vol. 473, p 77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Nelson KJ; Klomsiri C; Codreanu SG; Soito L; Liebler DC; Rogers LC; Daniel LW; Poole LB In Methods in Enzymology; Cadenas E, Packer L, Eds.; Elsevier Academic Press, Inc.: San Diego, 2010; Vol. 473, p 95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Sunitha K; Hemshekhar M; Thushara RM; Santhosh MS; Yariswamy M; Kemparaju K; Girish KS Free Radical Res 2013, 47, 357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.