Abstract

Context:

Traditional truncal blocks are devoid of visceral analgesia. Quadratus lumborum (QL) block has shown greater efficacy in providing the same.

Aims:

This study was done to compare the efficacy of transversus abdominal plane (TAP) block versus QL block in providing postoperative analgesia for lower abdominal surgeries.

Settings and Design:

This was a prospective, randomized, double-blinded study.

Subjects and Methods:

Seventy adult patients were randomly allocated into two groups, where Group A received TAP block with 20 ml of 0.25% ropivacaine on each side (n = 35) and Group B received QL block with 20 ml of 0.25% ropivacaine on each side (n = 35). The time of block, duration of surgery, Numerical Pain Intensity Scale (NPIS) score at the 1st, 2nd, 4th, 8th, 12th, 16th, and 24th postoperative hours, and the total analgesic drug requirements were noted and compared between the two groups.

Statistical Analysis Used:

Data were analyzed with SPSS version 23 (IBM corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) with independent t-test and Chi-square test as appropriate. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results:

The time for first analgesic requirement was 243.00 ± 97.36 min and 447.00 ± 62.52 min and the total analgesic consumption (morphine in mg) was 5.65 ± 1.55 and 3.25 ± 0.78 in Group A and Group B, respectively, both of which were statistically significant (P < 0.01). There was a significant difference in postoperative pain scores (NPIS scale 0–10) at rest, between the two groups, up to 16 h.

Conclusions:

Patients who received QL block had a significant improvement in postoperative pain relief with reduced consumption of opioids.

Keywords: Analgesia, pain management, quadratus lumborum, ropivacaine, transversus abdominis

INTRODUCTION

Effective postoperative pain management can positively influence patient outcome following any surgery. Side effects are the major concern with multimodal analgesic regimes. Epidural analgesia, though the most preferred mode for continuing postoperative analgesia, may still have disadvantages such as restricted mobility and negative cardiovascular and gastrointestinal consequences.[1] Most of the times patients require regional anesthetic techniques to minimize opioid use and provide an alternative to epidural anesthesia, especially for minimally invasive abdominal surgeries to improve the recovery.

Studies have shown the potential for improved recovery with ultrasound-guided transversus abdominis plane (TAP) block after various abdominal surgical procedures. This technique is opioid sparing and has demonstrated greater satisfaction with pain relief.[2] Conventional approaches such as TAP block provides effective somatic analgesia with minimal or no visceral blockade.[3] The need for visceral blockade to provide better postoperative pain relief led to a more posterior approach that involves injecting the local anesthetic adjacent to the quadratus lumborum (QL) muscle.[4,5]

This study was done to compare the efficacy of TAP block versus QL block in providing postoperative analgesia for lower abdominal surgeries.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS

This prospective, double-blinded study was done for a period of 6 months. The study included patients who underwent elective lower abdominal surgery under general anesthesia, aged between 18 and 60 years, and with a physical status of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) -I and II. Patients not consenting for block, those belonging to ASA-III, IV, and V physical status, patients allergic to local anesthetics and adjuvants, presence of infection at the needle insertion site, and patients currently using analgesics or who had current acute or chronic pain were excluded from the study.

Informed written consents were obtained from all patients and the technique of regional anesthesia explained. Approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board and the Institutional Human Ethics committee.

Seventy (70) adult patients of age group 18–60 years of either sex posted for elective lower abdominal surgery under general anesthesia were enrolled for the study. Patients were randomly allocated into one of the two groups (Group A or Group B) by computer-generated list of random numbers and were blinded from the technique. Blocks were performed by the attending anesthesiologists at the end of surgery. Patients were observed and monitored in the postanesthesia care unit by the nurses who were otherwise blinded to the block. Results were handed over to the investigator in a sealed envelope.

Following preanesthetic evaluation, all the patients included in the study were explained about Numerical Pain Intensity Scale (NPIS) in their own vernacular language (0 – no pain to 10 – worst imaginable pain). A premedication of 0.02 mg/kg of midazolam intravenous (IV) was administered about 20 min before induction of general anesthesia. Standard monitoring was done. General anesthesia was standardized in all patients. Propofol 1.5–2 mg/kg and fentanyl 3 μg/kg were given for induction of anesthesia. Tracheal intubation facilitated by administration of muscle relaxant. Anesthesia was maintained with N2O with O2(65%:35%), isoflurane 1 vol%, vecuronium 0.02 mg/kg every 30 min, and fentanyl 1 μg/kg/h. End-tidal CO2 concentration was maintained between 35 and 45 mmHg using mechanical ventilation.

The TAP block or the QL block was performed on each side at the end of the surgery and before extubation by the anesthesiologist under ultrasound guidance using a linear array transducer of 10Mhz frequency (MINDRAY) using an in-plane technique.

In a TAP block, with the patient in supine position, strict aseptic measures were taken. The transducer was placed between the iliac crest and costal margin, and three muscle layers were identified (external oblique, internal oblique, and transversus abdominis muscles). After identifying the TAP, the needle was guided through the subcutaneous tissue, external oblique, and internal oblique. When the needle reached the plane between the internal oblique and the transversus abdominis, a “pop” was felt. The location of the needle was verified and 20 ml of local anesthetic was injected into this plane.

Similarly, in a QL block, a linear transducer is placed between the iliac crest and costal margin in the midaxillary line and moved posteriorly so that the posterior aponeurosis of the transversus abdominis muscle is visible. The needle was targeted deep to the aponeurosis and superficial to the transversalis fascia, at the lateral margin of QL muscle. The same procedure was repeated on the both sides for all patients.

Group A received TAP block with 20 ml of 0.25% ropivacaine (ROPIN 0.5% diluted to 0.25%, Neon Laboratories Ltd, manufactured in India) on each side (n = 35) and Group B received QL block with 20 ml of 0.25% ropivacaine on each side (n = 35). The time of block and the duration of surgery would be noted. After the block, residual neuromuscular blockade was reversed with neostigmine 0.05 mg/kg and glycopyrrolate 0.01 mg/kg. Patients were extubated after thorough suctioning of the oral cavity.

Patients were transferred to the postanesthesia recovery unit. At the 1st, 2nd, 4th, 8th, 12th, 16th, and 24th postoperative hours, the NPIS score was recorded at rest, the time elapsed before the first analgesic request and the total analgesic drug requirements were compared between the two groups.

All patients were given acetaminophen 1 g IV every 8 h during the first 24 h after surgery. Patients were given IV boluses of 1 mg morphine when NPIS (0–10) score at rest was more than 4 at any time patients complain of pain and hemodynamics monitored. Ondansetron 4 mg IV was administered in case of reported nausea and/or vomiting. Any other side effects were noted.

The primary outcome measured was duration for requirement of first rescue analgesic, and the secondary outcomes measured were pain score (NPIS scale 0–10) at rest and total analgesic consumption (morphine in mg). A minimum sample size was 35 for each group with type-1α error of 0.05, with power of the study at 80%, hence we set the sample size of 70. The data was analysed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version 23, Microsoft USA, Armonk, NY: IBM corporation and its licensors 2015. They were expressed as mean ± standard deviation. Statistical Analysis was done by Independent T test or Mann Whitney U Test whichever applicable. The NPIS score was analysed using Chi square or Fishers exact t-test and data was expressed a mean±SD. A p-value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant for 2 sided test.

The study was registered in Clinical Trial registry India, CTRI/2017/06/008806.

RESULTS

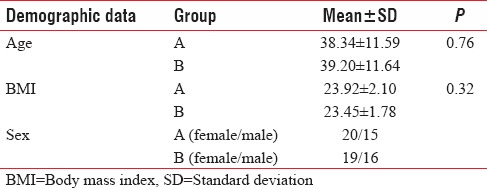

All the 70 patients randomized were included and analyzed for the study. The demographic data were comparable between the two groups in terms of age, sex, and body mass index [Table 1]. The duration of surgery was also comparable in both groups [Table 2].

Table 1.

Demographic data between groups (mean±standard deviation)

Table 2.

Duration of surgery

There was equal number of men and women in both groups [Table 1].

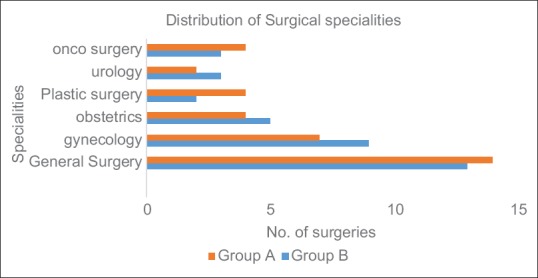

The number of patients involved in the study from different surgical specialties is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Surgical specialties

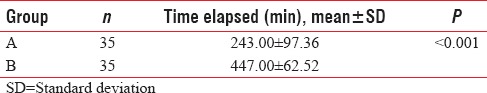

The time elapsed before the requirement of first additional analgesic was significantly more (P < 0.001; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 243.03–164.97) in the QL block group compared to the TAP block group [Table 3].

Table 3.

Time elapsed for the first analgesic request

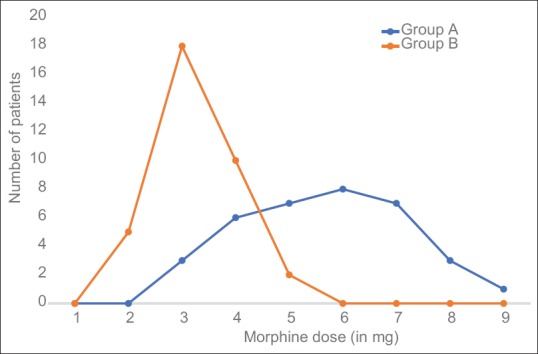

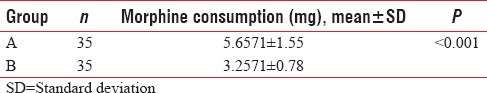

The dose of morphine required postoperatively is shown in Figure 2. The total morphine consumption was lesser in Group B (mean ± standard deviation [SD] – 5.6571 ± 1.55) compared to Group A (mean ± SD – 3.2571 ± 0.78) which was statistically significant (P < 0.001, 95% CI: 1.81–2.98) [Table 4].

Figure 2.

Total morphine consumption

Table 4.

Total morphine consumption

The mean pain scores (NPIS) at rest is shown in Table 5 for various time intervals. There was a significant difference in pain scores between the two groups at the 1st, 2nd, 4th, 6th, 8th, 10th, 12th, and 16th postoperative hours. There was no difference in the pain scores 24 h postsurgery indicating the wearing off the block in both the groups [Table 5].

Table 5.

Numerical pain intensity scale scores between Group A and Group B

DISCUSSION

Harvey Cushing's quote, “Almost all cases of hernia, with the possible exception of those in young children, could undoubtedly be subjected to the radical operation under local anesthesia,” reported in Annals in Surgery in 1900, is an evidence that regional anesthesia was appreciated for abdominal surgeries even 100 years ago.[6] Perioperative pain management using truncal nerve blocks became a part of anesthetic management for abdominal surgeries 40 years ago. Since then, newer techniques for truncal blocks are being introduced, such as the ilioinguinal-iliohypogastric block, rectus sheath block, TAP and QL blocks in the abdomen and the serratus anterior plane block, pectoral nerves block 1 and 2, and intercostal nerve block in the thorax.

The truncal block was brought into clinical practice when ilioinguinal-iliohypogastric block was found to be highly effective for pain relief during or after herniorrhaphy.[7,8] Rectus sheath block was initially described in 1899 for abdominal wall relaxation during laparotomy,[9] but later used regularly for umbilical and incisional hernia repair and surgical incisions involving midline.[10]

TAP block aims at blocking sensory neural pathways before they enter the abdominal wall musculature, either by landmark technique or ultrasound guided. As discussed earlier, TAP block provides effective somatic analgesia, but it is less effective in providing visceral analgesia.[3]

For the need of providing effective visceral analgesia, QL block was introduced in 2007 by anesthesiologist Dr. Rafael Blanco.[11] QL block has been shown to provide effective postoperative pain relief following gynecological laparoscopic surgeries and Cesarean section.[12] Its efficacy has also been proved to be high for gastrointestinal and renal surgeries too.[3]

This study was done to compare the efficacy of TAP block versus QL block in providing postoperative analgesia for lower abdominal surgeries. The approach followed during this study was QL1/lateral QL block. Ueshima et al. recently mentioned in a review article that, although there are four different approaches for this procedure, the best approach is yet to be validated and a personalized approach depending on the surgery would be a better option.[13] It is discernible from the study that QL block offers better postoperative analgesia. The various evidence in the study favoring QL block were, the longer time required for the first analgesic requirement, the lesser morphine dose required and lower NPIS score in these patients.

Most of the previous studies were done by comparing the blocks for one particular surgical technique, such as either cesarean section, total abdominal hysterectomy, or hernia repair. This study includes lower abdominal surgical procedures from all specialties, which makes this study unique. Yousef, in his study, compared TAP and QL blocks in women who underwent total abdominal hysterectomy.[14] Fentanyl and morphine requirement was less in the QL block group. Pain was scored using the visual analog scale, which was also significantly higher in the TAP block group. The results of the study were corresponding to our results in by all means.

Similar results have been published in earlier studies and the major advantage of QL block was considered to be its analgesic action similar to opioid analgesics, yet avoiding the adverse effects such as nausea and vomiting.[15] A randomized controlled trial found that most women required IV patient-controlled analgesia pump of morphine despite intrathecal administration of the drug. Therefore, there is sufficient evidence that adequate analgesia may not be achieved with intrathecal opioid administration alone.[16] Öksüz et al. compared both the blocks in children who underwent unilateral inguinal hernia repair or orchidopexy. Children who needed analgesia administration postoperatively, within the first 24 h, was significantly lesser in the QL block group (P < 0.05). Parent satisfaction scores were higher and the postoperative 30-min and 1-, 2-, 4-, 6-, 12-, and 24-h FLACC scores were also lower in the QL block group when compared to the TAP block group (P < 0.05).[17]

The adverse events associated with escalating doses of morphine, such as pruritus, nausea, somnolence, and respiratory depression can also be avoided by lower doses required with QL block. The topographically broader field of action (T6 to L1) and longer duration of pain-relief make it superior to TAP block in providing postoperative pain relief.[18,19] Although the duration of action differs with each study, there is a significant difference between TAP and QL blocks.[18]

Procedure-related complications are considerably less with QL block. There has been no report of infections following the procedure. The site of needle entry is distant from the abdominal viscera and large blood vessels, thus making the procedure much safer when compared to other abdominal wall blocks.[15]

CONCLUSIONS

We, hereby, conclude with the help of the present study and available literature that QL block would be a better option for providing postoperative analgesia during abdominal surgeries, in terms of duration for requirement of 1st rescue analgesic, better pain score at rest, and total opioid analgesic consumption. All these factors contribute to faster postoperative recovery and earlier mobilization of patient.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Findlay JM, Ashraf SQ, Congahan P. Transversus abdominis plane (TAP) blocks – A review. Surgeon. 2012;10:361–7. doi: 10.1016/j.surge.2012.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.White PF. The changing role of non-opioid analgesic techniques in the management of postoperative pain. Anesth Analg. 2005;101:S5–22. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000177099.28914.A7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akerman M, Pejčić N, Veličković I. A review of the quadratus lumborum block and ERAS. Front Med (Lausanne) 2018;5:44. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2018.00044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kadam VR. Ultrasound-guided quadratus lumborum block as a postoperative analgesic technique for laparotomy. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2013;29:550–2. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.119148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Visoiu M, Yakovleva N. Continuous postoperative analgesia via quadratus lumborum block – An alternative to transversus abdominis plane block. Paediatr Anaesth. 2013;23:959–61. doi: 10.1111/pan.12240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Henry L, Charles JF, Michael JY, Alan DK. Selective regional anesthesia options in surgical subspecialities. In: Alan DK, Richard DU, Nalini V, editors. Essentials of Regional Anesthesia. London: Springer Science and Business Media; 2011. p. 526. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ding Y, White PF. Post-herniorrhaphy pain in outpatients after pre-incision ilioinguinal-hypogastric nerve block during monitored anaesthesia care. Can J Anaesth. 1995;42:12–5. doi: 10.1007/BF03010564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison CA, Morris S, Harvey JS. Effect of ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerve block and wound infiltration with 0.5% bupivacaine on postoperative pain after hernia repair. Br J Anaesth. 1994;72:691–3. doi: 10.1093/bja/72.6.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Willschke H, Bösenberg A, Marhofer P, Johnston S, Kettner SC, Wanzel O, et al. Ultrasonography-guided rectus sheath block in paediatric anaesthesia – A new approach to an old technique. Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:244–9. doi: 10.1093/bja/ael143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yarwood J, Berrill A. Nerve blocks of the anterior abdominal wall. Contin Educ Anesth Crit Care Pain. 2010;10:182–6. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blanco R. TAP block under ultrasound guidance: The description of a ‘non pops technique’. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2007;32:130. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sebbag I, Qasem F, Dhir S. Ultrasound guided quadratus lumborum block for analgesia after cesarean delivery: Case series. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2017;67:418–21. doi: 10.1016/j.bjan.2017.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ueshima H, Otake H, Lin JA. Ultrasound-guided quadratus lumborum block: An updated review of anatomy and techniques. Biomed Res Int 2017. 2017 doi: 10.1155/2017/2752876. 2752876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yousef NK. Quadratus lumborum block versus transversus abdominis plane block in patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy: A randomized prospective controlled trial. Anesth Essays Res. 2018;12:742–7. doi: 10.4103/aer.AER_108_18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ishio J, Komasawa N, Kido H, Minami T. Evaluation of ultrasound-guided posterior quadratus lumborum block for postoperative analgesia after laparoscopic gynecologic surgery. J Clin Anesth. 2017;41:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2017.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Palmer CM, Emerson S, Volgoropolous D, Alves D. Dose-response relationship of intrathecal morphine for postcesarean analgesia. Anesthesiology. 1999;90:437–44. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199902000-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Öksüz G, Bilal B, Gürkan Y, Urfalioğlu A, Arslan M, Gişi G, et al. Quadratus lumborum block versus transversus abdominis plane block in children undergoing low abdominal surgery: A randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2017;42:674–9. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blanco R, Ansari T, Riad W, Shetty N. Quadratus lumborum block versus transversus abdominis plane block for postoperative pain after cesarean delivery: A randomized controlled trial. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016;41:757–62. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murouchi T, Iwasaki S, Yamakage M. Quadratus lumborum block: Analgesic effects and chronological ropivacaine concentrations after laparoscopic surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016;41:146–50. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0000000000000349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]