Abstract

Objective

Academic medical training was overhauled in 2005 after the Walport report and Modernising Medical Careers to create a more attractive and transparent training pathway. In 2007 and 2016, national web-based surveys of gastroenterology trainees were undertaken to determine experiences, perceptions of and perceived barriers to out-of-programme research experience (OOP-R).

Design, setting and patients

Prospective, national web-based surveys of UK gastroenterology trainees in 2007 and 2016.

Main outcome measure

Attitudes to OOP-R of two cohorts of gastroenterology trainees.

Results

Response rates were lower in 2016 (25.8% vs 56.7%) (p<0.0001), although female trainees’ response rates increased (from 28.8% to 37.6%) (p=0.17), along with higher numbers of academic trainees. Over 80% of trainees planned to undertake OOP-R in both surveys, with >50% having already undertaken it. Doctor of Philosophy/medical doctorate remained the most popular OOP-R in both cohorts. Successful fellowship applications increased in 2016, and evidence of gender inequality in 2007 was no longer evident in 2016. In the 2016 cohort, 91.1% (n=144) felt the development of trainee-led research networks was important, with 74.7% (n=118) keen to get involved.

Conclusions

The majority of gastroenterology trainees who responded expressed a desire to undertake OOP-R, and participation rates in OOP-R remain high. Despite smaller absolute numbers responding than in 2007, 2016 trainees achieved higher successful fellowship application rates. Reassuringly more trainees in 2016 felt that OOP-R would be important in the future. Efforts are needed to tackle potential barriers to OOP-R and support trainees to pursue research-active careers.

Keywords: academic medicine, out of programme, training

Introduction

Academic medicine and research are a vital part of medicine, facilitating improvements in patient management, patient experience and quality improvement within the National Health Service (NHS). Prior to the Walport report in 2005, there was no structured career path for doctors wishing to pursue an academic medical career.1 They often faced criticism for becoming clinically deskilled and were frequently poorly paid relative to clinical colleagues. These factors, coupled with perceived job insecurity, meant a worrying decline in academic medicine in the early 2000s, particularly among female doctors. A 2004 report by the Council of Heads of Medical Schools showed a 23% reduction in junior academic staff over the preceding 3 years and 10% of clinical academic posts unfilled.2 This was in the context of 40% more medical students up to 2005.1

In 2004 the government created the UK Clinical Research Collaboration to reignite and reinvigorate clinical research. After the Walport report, together with the Modernising Medical Careers academic careers subcommittee, they implemented a new structured academic career pathway.1

The Walport report aimed to resolve three keys issues faced by academic trainees: first, a lack of clear entry routes and transparent career structure; second, inflexibility in the academic/clinical training balance; and finally a paucity of structured, supported posts on training completion.1

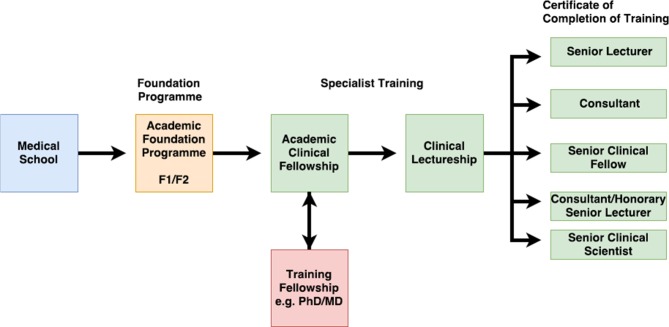

The newly created pathway allowed exposure to research within the foundation programme, allowing the pursuit of areas of interest, without the need for indepth research. After completion of foundation training, the newly formed academic clinical fellowships allowed dedicated research time, while gaining core specialty competencies. The aim of this fellowship was to create a research proposal and secure funding for a medical doctorate (MD) or Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), to be undertaken after specialty training (ST) year 3. Once completed the trainee returns to clinical training at ST4, as a clinical lecturer, to provide them with the opportunity to pursue postdoctoral research and complete clinical training (see figure 1). The overall aim of this pathway was to progress into senior academic roles. It also allowed flexibility to ‘side step’ from academic into clinical training and multiple entry points for ‘late bloomers’, although this latter benefit has been questionable.3

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the academic pathway introduced after the Walport report. MD, medical doctorate; PhD, Doctor of Philosophy.

In the wake of these extensive changes, a national survey of gastroenterology trainees was undertaken in 2007 to determine their attitudes towards, and experiences of, out-of-programme experiences/research (OOP-E/OOP-R).4 This information was passed to the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) to allow the development of initiatives to address any deficiencies. OOP-E, OOP-R and OOP-training (OOP-T) are the various approved OOP options to trainees. These may not count towards training (OOP-E), may partially count (OOP-R) or fully/partially count (OOP-T). These options give trainees the chance to pursue an area of interest outside of their training programme to gain extra clinical skills or experience or non-clinical skills that they would not normally have access to in their training programme. This survey was repeated in 2016 to assess for changes among subsequent gastroenterology trainees, and also expanded to cover more recent developments in research, such as trainee-led networks and the Clinical Research Network (CRN).

Methods

All UK gastroenterology trainees were surveyed, using a dedicated web-based platform. The survey was conducted in a national web-based format in 2007 and again in 2016. Trainees were identified from the BSG database and an email invitation was sent to all trainees via the BSG mailing list and the BSG trainees section regional representatives. A follow-up email was sent 4 weeks later and a final email reminder sent out via the regional training programme directors and trainee committee chairs.

The questionnaire was divided into six domains: (1) demographics, (2) general career intentions, (3) intention to pursue an OOP-E/OOP-R, (4) current or previous OOP-E/OOP-R, (5) perceptions of OOP-E/OOP-R and (6) future career benefits of OOP-E/OOP-R.

The same basic questionnaire was used for both cohorts. Extra questions relating to trainee-led research networks and Good Clinical Practice (GCP) were included in the 2016 questionnaire.

A full list of questions, including extra 2016 questions, can be found in table 1.

Table 1.

Full results of the 2007 and 2016 gastroenterology trainee surveys (numbers in brackets are absolute numbers)

| 2007 | 2016 | P values | |

| Response rate | 56.7% (274/483) | 25.8% (178/690) | <0.001 |

| Male:female | 71.2%:28.8% (195/79) | 62.4%:37.6% (111/67) | 0.06 |

| Training programme | |||

| NTN | 74.1% (203) | 55.7% (98) | |

| NTN (OOPE) | 20.4% (56) | 34.1% (60) | |

| LAT/LAS | 4.7% (13) | 1.7% (3) | 0.68 |

| NIHR Academic Clinical Fellow | 0% | 1.1% (2) | |

| NIHR Clinical Lecturer | 0% | 3.4% (6) | |

| Non-NIHR Academic Clinical Fellow | 0% | 0.6% (1) | |

| Non-NIHR Clinical Lecturer | 0% | 1.7% (3) | |

| Training level | |||

| ST3 | 12.0% (33) | 9.1% (16) | |

| ST4 | 15.0% (41) | 13.6% (24) | |

| ST5 | 26.6% (73) | 29.5% (52) | 0.12 |

| ST6 | 20.4% (56) | 27.8% (49) | |

| ST7 | 13.5% (37) | 14.8% (26) | |

| ST7+ | 12.4% (34) | 5.1% (9) | |

| Organisation membership | |||

| BSG | 52.2% (143) | 94.3% (166) | |

| RCP | 78.1% (214) | 61.9% (109) | <0.01 |

| BASL | 9.5% (26) | 26.7% (47) | |

| BAPEN | Not surveyed | 6.3% (11) | |

| AGA | Not surveyed | 9.7% (17) | |

| AASLD | Not surveyed | 5.1% (9) | |

| EASL | Not surveyed | 19.3% (34) | |

| Career intentions: specialisation | |||

| Luminal gastroenterology | 26.31% (71) | 62.2% (107) | |

| Hepatology | 20.2% (55) | 11.0% (19) | 0.39 |

| Both | 39.7% (108) | 23.8% (41) | |

| Unsure | 14.0% (38) | 2.9% (5) | |

| Career intentions: career structure | |||

| NHS consultant with GIM | 59.7% (163) | 63.4% (109) | |

| NHS consultant with academic interest | 31.5% (86) | 19.2% (33) | 0.58 |

| Academic pathway | 8.8% (24) | 7.6% (13) | |

| Part-NHS/Part-university | 0% (0) | 9.9% (17) | |

| Feel that a higher degree will help get a non-academic NHS job? | |||

| Yes | 86.3% (234) | 81.4% (140) | 0.16 |

| No | 13.7% (37) | 18.6% (32) | |

| Feel that a higher degree will make you more competitive at consultant interview? | |||

| Yes | 94.1% (257) | 93.6% (161) | 0.82 |

| No | 5.9% (16) | 6.4% (11) | |

| Do you intend/have you undertaken an OOP-E/research? | |||

| Yes | 81.7% (223) | 84.9% (146) | 0.12 |

| No | 14.7% (40) | 15.1% (26) | |

| Unsure | 3.7% (10) | 0% (0) | |

| What type of OOP-E/OOP-R you intend to undertake? (can select more than one) | |||

| PhD | 47.1% (105) | 50.7% (74) | |

| MD | 49.8% (111) | 41.8% (61) | 0.42 |

| MSc | 13.0% (29) | 16.4% (24) | |

| MPhil | 1.3% (3) | 2.7% (4) | |

| Other | 15.7% (35) | 6.2% (9) | |

| When is the ideal time to undertake OOP-E/OOP-R? | |||

| Medical student | 0.7% (2) | 0.7% (1) | |

| Core training years | 2.9% (8) | 1.4% (2) | |

| ST3–ST4 | 21.3% (58) | 14.6% (21) | 0.68 |

| ST5–ST6 | 71.0% (193) | 77.8% (112) | |

| ST7+ | 2.9% (8) | 5.6% (8) | |

| Are you aware that OOP-E/OOP-R can count to CCT? | |||

| Yes | 91.1% (246) | 81.3% (117) | <0.01 |

| No | 8.9% (24) | 18.8% (27) | |

| Are you aware that deaneries discourage OOP-E/OOP-R in the final training year? | |||

| Yes | 63.0% (170) | 68.1% (98) | 0.3 |

| No | 37.0% (100) | 31.9% (46) | |

| Are you currently, or have you completed, an OOP-E/OOP-R? | |||

| Yes | 50.2% (136) | 69.4% (100) | <0.01 |

| No | 49.8% (135) | 30.6% (44) | |

| What field was research in? | |||

| Basic science | 69.9% (121) | 41.9% (49) | |

| Epidemiology | 5.8% (10) | 7.7% (9) | |

| Nutrition | 5.2% (9) | 4.3% (5) | 0.26 |

| Medical education | 4.6% (8) | 3.4% (4) | |

| Endoscopy | 4.6% (8) | 13.7% (16) | |

| Other | 9.8% (17) | 29.1% (34) | |

| What further degree did you register for? | |||

| PhD | 43.6% (61) | 52.5% (53) | |

| MD | 40.7% (57) | 40.6% (41) | 0.63 |

| MSc | 11.4% (16) | 3.0% (3) | |

| Other | 4.3% (6) | 4.0% (4) | |

| If OOP-E/OOP-R completed, has your degree been awarded? | |||

| Yes | 47.3% (35) | 56.5% (26) | 0.16 |

| No | 52.7% (39) | 43.5 (20) | |

| Fellowship application success rates | |||

| CRUK | 23.5% (4) | 42.9% (3) | |

| Wellcome | 24% (12) | 42.9% (12) | |

| CORE | 23.7% (14) | 45.5% (5) | 0.13 |

| MRC | 29.9% (23) | 50% (8) | |

| Action Medical | 7.7% (1) | 0% (0) | |

| Other | 57.5% (69) | 84% (21) | |

| Prefunded | 41.1% (39) | 75% (27) | |

| Would you be willing to move region for OOP-E/OOP-R? | |||

| Yes | 62.1% (169) | 59.7% (83) | 0.63 |

| No | 37.9% (103) | 40.3% 56) | |

| Which of the following would make you want to undertake an OOP-E/OOP-R? | |||

| Academic interest | 83.5% (227) | 79.1% (110) | |

| Career prospects | 56.3% (153) | 89.2% (124) | |

| Educational benefits | 86.0% (234) | 78.4% (103) | 0.11 |

| Travel | Not surveyed | 24.5% (34) | |

| Break from GIM/gastroenterology | 51.8% (141) | 69.8% (97) | |

| Career advice from senior | 58.1% (158) | 31.7% (44) | |

| Do you agree or disagree with the following reasons for not undertaking OOP-E? | Strongly agree/agree | Strongly disagree/disagree | Strongly agree/agree | Strongly disagree/disagree | |

| Financial cost | 72.1% (196) | 21.3% (58) | 69.7% (115) | 21.2% (35) | |

| Personal choice | 75.8% (206) | 11.7% (32) | 81.8% (135) | 10.3% (17) | |

| Pre-existing debt | 42.6% (116) | 33.3% (55) | 52.7% (87) | 33.3% (55) | 0.48 |

| Little perceived career benefit | 9.5% (26) | 73.6% (200) | 23% (38) | 64.9% (107) | |

| Do you believe that OOP-E/OOP-R will be important in the future? | |||||

| Yes | 80.9% (220) | 88.9% (144) | 0.03 | ||

| No | 19.1% (52) | 11.1% (18) | |||

| Extra to 2016 survey | |||||

| Do you currently hold a GCP certificate? | |||||

| Yes | 63.0% (104) | ||||

| No | 37.0% (61) | ||||

| Have you recruited into a CRN portfolio research study? | |||||

| Yes | 47.3% (78) | ||||

| No | 52.7% (87) | ||||

| Do you have a peer-reviewed publication within the last 2 years? | |||||

| Yes | 64.2% (106) | ||||

| No | 35.8% (59) | ||||

| Are you aware of the academic training programme? | |||||

| Yes | 67.3% (111) | ||||

| No | 32.7% (54) | ||||

| Do you feel a web-based BSG directory of OOP-E/OOP-R opportunities would be beneficial? | |||||

| Yes | 89.4% (144) | ||||

| No | 10.6% (17) | ||||

| Do you believe developing regional trainee-led networks is important? | |||||

| Yes | 91.1% (144) | ||||

| No | 8.9% (14) | ||||

| Would you like to get involved in such networks? | |||||

| Yes | 74.7% (118) | ||||

| No | 8.9% (14) | ||||

| Unsure | 16.5% (26) | ||||

AASLD, American Association for the Study of Liver Disease; AGA, American Gastroenterological Association; BAPEN, British Association for Parenteral and Enteral Nutrition; BASL, British Association for the Study of the Liver; BSG, British Society of Gastroenterology; CCT, Certificate of Completion of Training; CRN, Clinical Research Network; CRUK, Cancer Research UK; EASL, European Association for the Study of the Liver; GCP, Good Clinical Practice; GIM, General Internal Medicine; LAS, Locum Appointment for Service; LAT, Locum Appointment for Training; MD, medical doctorate; MRC, Medical Research Council; NHS, National Health Service; NIHR, National Institute for Health Research; NTN, national training number; OOP-E/OOP-R, out-of-programme experiences/research; PhD, Doctor of Philosophy; RCP, Royal College of Physicians; ST, specialty training.

Statistical analysis

Answers from the questionnaire were collated and analysed. The results are presented as percentages, and statistical comparisons between the cohorts were performed using χ2, Fisher’s exact test and one-way analysis of variance using SPSS v24. P<0.05 was adopted as the statistical criterion.

Results

The BSG database reported 483 UK gastroenterology trainees in 2007, of whom 274 responded (56.7%). In 2016, despite higher trainee numbers (690), only 178 responded (25.8%; see table 1).

In 2007, 28.7% (n=79) of the respondents were female, compared with 37.6% (n=67) in 2016 (p=0.06). There was no significant difference in trainee distribution by year of training (p=0.12), nor in the distribution between national training number (NTN) posts (both in programme and undertaking OOP-R), and academic training programme clinical fellows and clinical lecturers.

Career intentions and structure

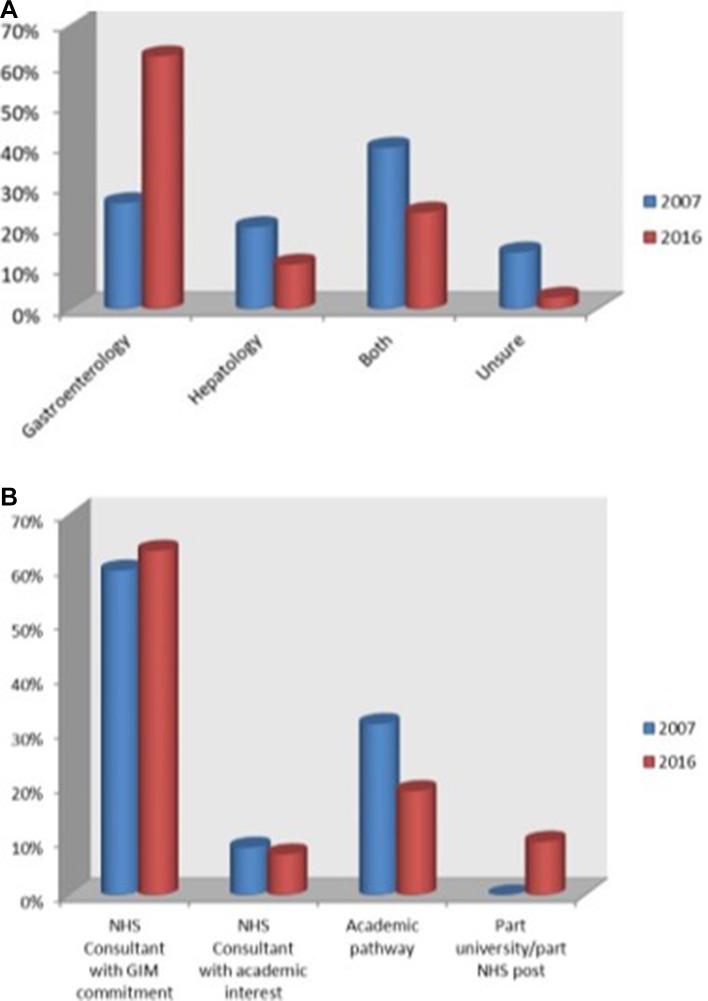

There was no significant difference between the 2007 and 2016 trainee cohorts in future career intentions (p=0.39). Of the respondents, 62.2% (n=107) were planning a career in luminal gastroenterology in 2016, from 26.1% (n=71) in 2007. In 2016, 11% (n=19) planned to pursue hepatology, down from 20.2% (n=55) in 2007. In our trainee cohorts, 23.8% (n=41) of 2016 and 39.7% (n=108) of 2007 trainees planned to practise general gastroenterology, and fewer 2016 trainees, 2.9% (n=5) remained unsure, compared with 14.0% (n=38) in 2007 (see figure 2A).

Figure 2.

(A) Career intentions of 2007 and 2016 trainee cohorts in terms of gastroenterology/hepatology. (B) Career intentions of 2007 and 2016 trainee cohorts in terms of planned career structure. GIM, general internal medicine; NHS, National Health Service.

There was no significant difference between the two cohorts in planned career structure (p=0.57). Of the respondents, 63.4% (n=109) in 2016 and 59.7% (n=163) in 2007 planned to practise as NHS consultants (luminal gastroenterology/hepatology) with general internal medicine commitments, while 7.6% (n=13) in 2016 and 8.8% (n=24) in 2007 planned to follow the academic pathway. The greatest changes were found in those planning to an NHS consultant career with an academic interest, with only 19.2% (n=33) in 2016 compared with 31.5% (n=86) in 2007. In 2007, no trainees had planned to pursue a shared university/NHS post, compared with 9.9% (n=17) in 2016 (see figure 2B).

Attitude to research degrees

Attitudes towards the role of higher research degrees remained consistent between the cohorts. Of the respondents, 86.3% (n=234) in 2007 and 81.4% (n=140) in 2016 believed that a higher degree would help obtain non-academic NHS jobs, and 94.1% (n=257) of 2007 and 93.6% (n=161) of 2016 respondents felt it would increase their competitiveness at consultant interviews (p=0.82).

The majority of trainees intended to undertake or had already undertaken an OOP-R: 81.7% (n=223) of 2007 and 84.9% (n=146) of 2016 respondents (p=0.12). The most popular OOP activities remain research-based, with 50.7% (n=74) in 2016 and 47.1% (n=105) in 2007 planning to undertake a PhD, and 41.8% (n=61) in 2016 and 49.8% (n=111) in 2007 planning an MD.

In the 2007 cohort, 54.4% (n=82) had completed their OOP-R and 47.3% (n=39) of these had received their degree. In 2016, 45.5% (n=46) had completed their OOP-R and 56% (n=26) of these had received their degree. Of those who had completed their OOP-R, 43.6% (n=61) and 40.7% (n=57) had been awarded a PhD or MD in 2007 compared with 52.5% (n=53) and 40.6% (n=41) in 2016.

There was no statistical difference between research type undertaken for OOP-R (p=0.26), with 69.9% (n=121) in 2007 and 41.9% (n=49) in 2016 undertaking basic science research, 5.8% (n=10) of 2007 and 7.7% (n=9) of 2016 trainees undertaking epidemiological research, and 5.2% (n=9) of 2007 and 4.3% (n=5) of 2016 respondents undertaking nutrition research. There was, however, an increased proportion of endoscopy-based research from 4.6% (n=8) in 2007 to 13.7% (n=16) in 2016 (p<0.05).

Both cohorts believed OOP-R was best undertaken at ST5–ST6, with 77.8% (n=112) in 2016 and 71% (n=193) in 2007 responding thus. Only 5.6% (n=8) in 2016 and 2.9% (n=8) in 2007 believed ST7 or above was the best career point for OOP-R (p=0.68). This is reflected in 68.1% (n=98) of 2016 and 63.0% (n=170) of 2007 trainees being aware that deaneries discourage OOP-R for final-year trainees (p=0.30). Most trainees were aware that OOP-R could count towards Certificate of Completion of Training (CCT) : 81.3% (n=117) of 2016 and 91.1% (n=246) of 2007 trainees.

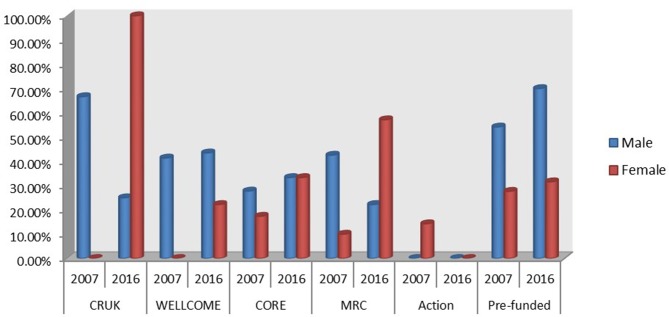

Fellowship applications

In 2007 there were 176 fellowship/research funding applications from 274 trainees compared with 120 applications from 178 trainees in 2016. Much higher success rates were reported in 2016 (48.4% vs 29.6%), although this was not statistically significant (p=0.13). Subanalysis of applications by gender revealed success rates of 41.8% (2007) and 41.9% (2016) for male applicants and 15.1% (2007) and 35.9% (2016) for female applicants. The only statistically significant difference occurred between the male and female 2007 cohorts (p=0.03). By 2016 this gender difference appears to have resolved (p=0.63) (see figure 3).

Figure 3.

Graph of fellowship application success rates for male and female trainees in 2007 and 2016 trainee cohorts. CRUK, Cancer Research UK; MRC, Medical Research Council.

Factors affecting trainees’ decisions about undertaking OOP-R

Motivations for undertaking an OOP-R were similar between cohorts; 83.5% (n=227) in 2007 and 79.1% (n=110) in 2016 wanted to pursue an academic interest, 56.3% (n=153) in 2007 and 89.2% (n=124) in 2016 wanted to enhance career prospects, 86% (n=234) in 2007 and 78.4% (n=103) in 2016 undertook for educational benefits, 51.8% (n=141) in 2007 and 69.8% (n=97) in 2016 wanted a break from acute medicine/gastroenterology, while 58.1% (n=158) in 2007 and 31.7% (n=44) in 2016 undertook OOP-R after career advice from senior colleagues.

When asked about agreement with often-stated reasons for not undertaking an OOP-R, more than 70% of the 2016 and 2007 cohorts strongly agreed/agreed that financial cost and personal choice were reasons for not undertaking OOP-R, while many agreed pre-existing debts were also a reason. More than 65% of both cohorts disagreed/strongly disagreed that OOP-R had little perceived career benefit.

GCP, portfolio studies and trainee research networks

Further questions added to the 2016 questionnaire revealed 63% (n=104) of the respondents held an active GCP certificate, which is a requirement of the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care 2005 for involvement in research, while 47.3% (n=78) had recruited participants into a CRN portfolio-adopted research study (https://www.nihr.ac.uk/research-and-impact/nihr-clinical-research-network-portfolio). Of the respondents, 64.2% (n=106) had at least one peer-reviewed publication within the preceding 2 years, and 67.3% (n=111) were aware of academic training programmes. Of the respondents, 89.4% (n=144) felt that a web-based BSG directory of OOP-R opportunities would be beneficial, and 91.1% (n=144) felt that regional trainee research network development was important, with 74.7% (n=118) keen to get involved in such networks.

Finally, 80.9% (n=220) in 2007 and 88.9% (n=144) in 2016 believed that OOP-R/research would be important in the future. Table 2 shows the ranking of which type of OOP experience candidates felt would best help their future career prospects.

Table 2.

Ranking of the type of OOP-R candidates felt would best help their future career prospects

| 2007 Rank | 2016 Rank | |

| 1st | PhD/MD | PhD/MD |

| 2nd | Endoscopy fellowship | Therapeutic endoscopy course |

| 3rd | Therapeutic endoscopy course | Management training/MSc |

| 4th | Management training/MSc | Endoscopy fellowship |

| 5th | Teaching diploma/MSc | ERCP training |

| 6th | Nutrition training/MSc | Teaching diploma/MSc |

| 7th | MSc (gastroenterology) | Nutrition training/MSc |

| 8th | ERCP training | MSc (gastroenterology) |

| 9th | Capsule endoscopy | Capsule endoscopy |

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; MD, medical doctorate; OOP-R, out-of-programme research; PhD, Doctor of Philosophy.

Discussion

Our analysis of the attitudes of two cohorts of gastroenterology trainees from 2007 and 2016 towards OOP-R shows research is clearly still considered relevant and an important part of gastroenterology training, with OOP-R remaining the most common form of OOP undertaken despite changes to the curriculum over the last 10 years.

Most trainees expressed a desire to undertake OOP-R, and participation rates remain high. Indeed, the proportion of trainees who felt that OOP-R was important, both for personal development and for wider NHS benefits, increased. This is reassuring and should be supported and promoted by the BSG. Some of these increases may reflect reporter bias, as there were fewer 2016 respondents, and a larger proportion of post-OOP-R trainees, leading to lower absolute numbers for 2016 responses.

Most 2016 respondents remained trainees with an NTN, or NTN OOP-R, although there were increases in academic pathway trainee numbers, as expected in the decade after the pathway introduction. Despite this, trainees planning to follow an academic pathway remained largely static; indeed the proportion of trainees planning to practise as full-time NHS consultants with academic interest also fell, although those planning to follow a part-university/NHS career increased from 0% to 10%. This may well reflect a lack of awareness and education at medical school/foundation levels of the academic career structure, although further study would be needed to determine if this is the case.

Interestingly, trainees appeared more decisive on their future careers, with a larger proportion choosing luminal gastroenterology compared with 2007 (62% vs 26%). This may reflect the higher proportion of post-OOP-R trainees completing the 2016 survey, but again could owe to reporting error from the smaller 2016 sample size. Fewer trainees planned to pursue hepatology or to practise in both disciplines, and fewer were unsure. This again could reflect reporter bias given the lower respondents in 2016, but warrants further investigation to determine why trainees appear currently to be more drawn towards luminal gastroenterology, rather than hepatology. It is worth mentioning the advent of the advanced training programme ST6 modules, which are now available but which were not available in 2007. These modules give trainees access to further training in endoscopy, nutrition, hepatology and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) among other areas without the need to take time OOP. These may well have had a role in influencing trainees’ careers intentions and subspecialisation plans.

Both cohorts agreed that the optimum time to undertake an OOP-R during their training is at the ST5–ST6 level. This belief is in opposition to the Walport report suggestion that academic trainees should undertake OOP-R at the ST3–ST4 level. This most likely reflects the fact that trainees undertaking OOP-R are often expected to provide service endoscopy lists to help fund their salary. To be independent for upper and or lower gastrointestinal endoscopy would mean that mostly only more senior trainees would be able to undertake OOP-R. The numbers of academic trainee respondents were too small for a meaningful analysis, so it is unclear if this reflects differences in attitudes of NTN and academic trainees, or a belief across all trainees.

Successful fellowship application rates improved between 2007 and 2016, despite a lower number of applications overall. This is most likely reflective of the lower numbers of responses in 2016, with a higher number of post-OOP-R responders. Significant differences in success at fellowship application were seen between male and female trainees in 2007. These now, reassuringly, appear to no longer be present in the current trainee cohort. This may be a result of reporter bias, or reflective of the advent of initiatives such as the Supporting Women in Gastroenterology, which began in 2014, and Athena SWAN. London-based trainees experienced a higher success rate of fellowship applications in both 2007 and 2016, although these were not to statistically significant levels.

Nearly two-thirds of 2016 trainees possessed an active GCP certificate (n=104) and had a peer-reviewed publication within the last 2 years (n=106), showing current and ongoing research involvement. Of those with current GCP certificates, 42% (n=44) were NTN trainees in training posts and 45% (n=47) were NTN trainees undertaking OOP-R. Interestingly, 47% of trainees had recruited patients to a CRN-adopted study, 48% of these being NTN trainees in training posts and 45% NTN trainees undertaking OOP-R. This highlights a potentially exploitable area to increase trainee involvement in both research and the CRN, that is, involving trainees as subinvestigators on portfolio-adopted studies, including commercial studies.

The 2016 cohort felt that the development of trainee-led research networks was important, with over three-quarters keen to get involved. There are, at present, three gastroenterology trainee-led networks in the UK: Gastroenterology Audit and Research Network, West Midlands Research in Gastroenterology Group, and Gastroenterology Trainee Research and Improvement Network – North West. These have been set up in the wake of the surgical trainee network success (Student Audit and Research in Surgery (STARSurg)), which has multiple publications and clinical trials.5–9

Beyond gastroenterology, a wider survey of Clinical and Health Research Fellowships was conducted in 2017 by the Medical Research Council (MRC).10 It highlighted that between 2009 and 2017, there was an increase in medically qualified research fellows at all academic career stages of 38% (1343–2149). However, this was front-loaded, with most increases found in the acaedmic clinical fellow (ACF) (291–877), doctoral (444–578) and clinical lectureship stages (225–427). The number of established independent researcher fellowships decreased from 178 to 83, and senior academic appointments only increased by 47% (32–47).10 These findings suggest that while the accessibility to the earlier stages of academic medical careers has increased, that progress is needed in later stages to remove the current ‘bottle neck’ effect,10 although this may represent a lag phase between the ending of the Clinical Senior Lectureship Awards scheme from the 2009 survey and the relatively early career phases of most academic trainees.

Reassuringly for academic medicine’s future, interest remains high, with increased numbers of predoctoral, doctoral and initial postdoctoral fellowship posts highlighted by the MRC survey.10 This was reflected in the gastroenterology survey with an increased proportion of trainees who felt that OOP-R would be important in the future. Efforts are needed to tackle the reported barriers to OOP-R and research, such as financial impact. In the future there is likely to be further barriers to undertaking OOP-R due to the pressures of service delivery within the NHS and the proposed changes to the shape of medical specialty training. These barriers need to be anticipated and pre-emoted to ensure that trainees are provided with the requisite support to pursue research-active careers and strengthen the future of academic medicine, regardless of academic or NHS career path.

Significant of this study.

What is already known on this topic

Academic medical training is a vital part of medicine.

The Walport report led to an overhaul of the academic medical training pathway to make it more attractive.

Out-of-programme research (OOP-R) is how most clinical trainees become involved in academic medicine.

What this study adds

Highlights the attitudes towards academic medicine and OOP-R of two cohorts of UK gastroenterology trainees from 2007 and 2016.

Highlights that interest in academic medicine/OOP-R remains high.

Most trainees believe that research/academic medicine is important to the future of the National Health Service.

How might it impact on clinical practice in the foreseeable future

Improve trainee participation in research, including commercial studies.

Increase awareness of trainee-led research networks.

Address the perceived obstacles towards trainees pursuing OOP-R/academic medicine.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the gastroenterology trainees for their participation in the research questionnaires.

Footnotes

Contributors: MM: data analysis, manuscript writing; NB, LC, LA, FC, BRD, ADF, EF, GS: data collection, manuscript writing; MAH, JM, HE, JS: manuscript preparation; MJB: data collection, manuscript writing, project guarantor.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: Further data are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Modernising Medical Careers and the UK Clinical Research collaboration. Medically- and dentally-qualified academic staff: Recommendations for training the researchers and educators of the future, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Medical Schools Council. Clinical Academic Staffing Levels in UK Medical and Dental Schools: A survey by the Council of Heads of Medical Schools and the Council of Deans of Dental Schools. London: Medical Schools Council, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Walport 10th Anniversary Symposium Goodenough College. https://www.bma.org.uk/-/media/files/pdfs/developing_your_career/finawalport-symposium-report.pdf

- 4. Bhala N, China L, AlRaiby L, et al. PTU-001 Attitudes of uk gastroenterology trainees to research and out of programme experience: results from the 2016 national academic training survey. Gut 2009;66:A150. [Google Scholar]

- 5. STARSurg Collaborative. Medical research and audit skills training for undergraduates: an international analysis and student-focused needs assessment. Postgrad Med J 2018;94:postgradmedj-2017-135035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. STARSurg Collaborative. Students' participation in collaborative research should be recognised. Int J Surg 2017;39:234–7. 10.1016/j.ijsu.2017.01.114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. STARSurg Collaborative. Safety of Nonsteroidal Anti-inflammatory Drugs in Major Gastrointestinal Surgery: A Prospective, Multicenter Cohort Study. World J Surg 2017;41:47–55. 10.1007/s00268-016-3727-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. STARSurg Collaborative. Multicentre prospective cohort study of body mass index and postoperative complications following gastrointestinal surgery. Br J Surg 2016;103:1157–72. 10.1002/bjs.10203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. STARSurg Collaborative. Outcomes After Kidney injury in Surgery (OAKS): protocol for a multicentre, observational cohort study of acute kidney injury following major gastrointestinal and liver surgery. BMJ Open 2016;6:e009812 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009812 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Medical Research Council. 2017 UK-Wide survey of clinical and health research fellowships. London: Medical Research Council, 2017. [Google Scholar]