Summary of recommendations

We recommend that all registered nursing and allied healthcare professionals work within their code of conduct at all times.

We recommend that all patients receive care supervised by a registered nurse who is accountable for their care throughout their time in the endoscopy department.

We recommend that delegation of responsibilities is considered, and only delegated to an individual deemed competent to undertake the task. All staff competencies should be clearly displayed in the endoscopy unit.

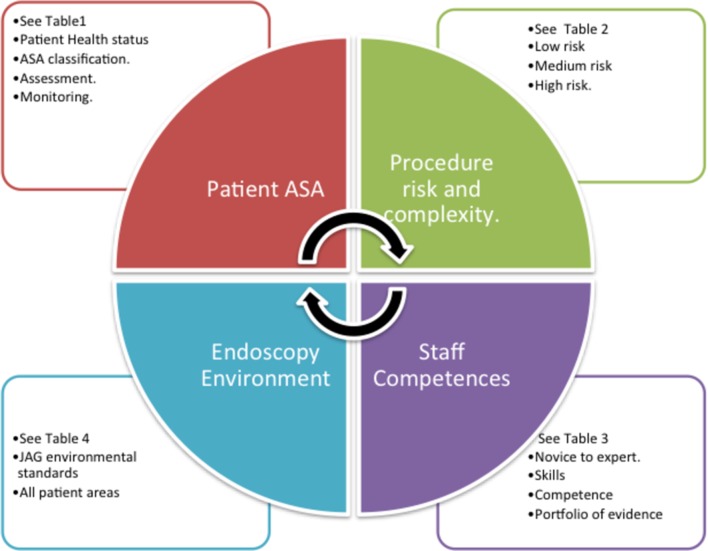

We recommend that thorough assessments of patient health status are undertaken before, during and after endoscopy procedures by a competent registered practitioner (table 1 and figure 1).

We recommend that staff who assist with complex procedures, or manage the care of patients with complex needs, should demonstrate a high level of relevant competence. This should be both in the technical aspects of endoscopic procedures, and the higher levels of assessment and monitoring required in patients at greater risk of deterioration or complications (tables 1 and 2).

We recommend that preprocedure checklists are undertaken, and all aspects of care throughout the procedure, including any changes in health status, must be documented and reported to the endoscopist.

We recommend that all staff have access to education and training, in line with endoscopy national frameworks, to meet professional standards, with regular appraisals of performance and competence to support staff development and professional revalidation.

We recommend that all staff actively participate in their own educational and skill development (table 3).

We recommend that all staff have a portfolio of competencies reflecting their education and training. This includes assessments of their competencies by senior registered staff, and evidence to support to their learning and revalidation. All endoscopy services must have an education, mentorship and supervision programme for all staff.

We recommend that due consideration is given to the endoscopy environment. All areas where patients are cared for must have the appropriate staffing skill mix to support patients’ needs.

We recommend that managers consider the numbers of staff, their qualifications, skill mix and competencies. There must be registered staff responsible for the supervision and direction of appropriate care at each step of the patient journey (figure 1).

We recommend that service managers, endoscopy nursing leads and clinical leads are responsible for planning future service delivery collaboratively. This should include workforce requirements to meet national guidance and local requirements.

Table 1.

ASA physical status classification system

| ASA PS classification | Definition | Examples, including but not limited to: |

| ASA I | A normal healthy patient | Healthy, non-smoking, no or minimal alcohol use |

| ASA II | A patient with mild systemic disease | Mild diseases only without substantive functional limitations. Examples include (but not limited to): current smoker, social alcohol drinker, pregnancy, obesity (30<BMI<40), well-controlled DM or HTN, mild lung disease. |

| ASA III | A patient with severe systemic disease | Substantive function limitation; one or more moderate to severe diseases. Examples include (but not limited to): poorly controlled DM or HTN, COPD morbid obesity (BMI>40), active hepatitis, alcohol dependence or abuse, implanted pacemaker, moderate reduction or ejection fraction. ESRD undergoing regularly scheduled dialysis, history (>3 months of MI, CVA, TIA or CAD/stents). |

| ASA IV | A patient with severe systemic disease that is a constant threat to life | Examples include (but not limited to) recent (<3 months) MI, CVA, TIA or CAD/stents ongoing cardiac ischaemia or severe valve dysfunction, severe reduction or ejection fraction, sepsis DIC, ARD or ESRD not undergoing regularly scheduled dialysis. |

| ASA V | A moribund patient who is not expected to survive | Examples include (but not limited to) ruptured abdominal/thoracic aneurysm, massive trauma, intracranial bleed with mass effect, ischaemic bowel in the face of significant cardiac pathology or multiple organ/systemic dysfunction. |

| ASA VI | A patient declared brain dead whose organs are being removed for donor purposes |

ARD, acute respiratory distress; BMI, body mass index; CAD, coronary artery disease; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CVA, cerebrovascular accident; DIC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; DM, diabetes mellitus; ESRD, end-stage renal disease; HTN, hypertension; MI, myocardial infarction; PS, physical status; TIA, transient ischaemic attack.

Figure 1.

Considerations for endoscopy staffing levels. JAG, Joint Advisory Group.

Table 2.

Procedure complexity matrix

| Procedure risk level | Low risk | Medium risk | High risk |

| Procedure | OGD Flexible sigmoidoscopy Polyp <1 cm |

OGD Flexible sigmoidoscopy Polypectomy >1 cm <2 cm or multiple polypectomy Colonoscopy Polypectomy >1 cm <2 cm EUS FNA Argon plasma coagulation Enteroscopy PEG |

GI bleed Dilatation Therapeutic OGD Variceal banding EMR ESD ERCP/Spyglass© GA PEXACT© Polypectomy >2 cm or multiple polypectomy |

EMR, endoscopic mucosal resection; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography; ESD, endoscopic submucosal dissection; FNA, fine needle aspiration; GA, general anaesthetic; GI, gastrointestinal; OGD, oesophagogastroduodenoscopy; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy.

Table 3.

Novice to expert: excellence and power in clinical nursing practice (summarised from Benner 18 )

| The novice or beginner has no experience in the situations in which they are expected to perform. The novice lacks confidence to demonstrate safe practice and requires continual verbal and physical cues. Practice is within a prolonged time period and he/she is unable to use discretionary judgement. |

| Advanced beginners demonstrate marginally acceptable performance because the nurse has had prior experience in actual situations. He/she is efficient and skilful in parts of the practice area, requiring occasional supportive cues. May/may not be within a delayed time period. Knowledge is developing. |

| Competence is demonstrated by the nurse who has been on the job in the same or similar situations for 2 or 3 years. The nurse is able to demonstrate efficiency, is coordinated and has confidence in his/her actions. For the competent nurse, a plan establishes a perspective, and the plan is based on considerable conscious, abstract, analytic contemplation of the problem. The conscious, deliberate planning that is characteristic of this skill level helps achieve efficiency and organisation. Care is completed within a suitable time frame without supporting cues. |

| The proficient nurse perceives situations as a whole rather than in terms of chopped up parts or aspects. Proficient nurses understand a situation as a whole because they perceive its meaning in terms of long-term goals. The proficient nurse learns from experience what typical events to expect in a given situation and how plans need to be modified in response to these events. The proficient nurse can now recognise when the expected normal picture does not materialise. This holistic understanding improves the proficient nurse’s decision-making; it becomes less laboured because the nurse now has a perspective on which of the many existing attributes and aspects in the present situation are the important ones. |

| The expert nurse has an intuitive grasp of each situation and zeroes in on the accurate region of the problem without wasteful consideration of a large range of unfruitful, alternative diagnoses and solutions. The expert operates from a deep understanding of the total situation. His/her performance becomes fluid and flexible and highly proficient. Highly skilled analytic ability is necessary for those situations with which the nurse has had no previous experience. |

Introduction

The Joint Advisory Group (JAG) on Gastrointestinal Endoscopy provides an accreditation process for endoscopy services in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.1 JAG accreditation standards have demonstrated improvement in the quality of endoscopy services for patients. Patients undergoing endoscopy procedures expect support and care from a competent healthcare team. The original endoscopy guidance on workforce was published in Gut in 19872; since then there have been significant developments in endoscopy techniques and the way endoscopy services are delivered in all the home nations of the UK. JAG does not state the numbers of staff required for an endoscopy unit as there are variations in the environment, procedure types and patients’ health status. This document makes a number of recommendations to guide managers’ decision-making on safe staffing levels.

There are many job titles and a diversity of roles within endoscopy services nationally. For the purpose of this document we have referred to registered nurses (RN) and to healthcare support workers (HCSW). We refer to HCSW as all staff not registered with a professional body. Where healthcare providers employ other allied healthcare professions, for example, operating department practitioners (ODP), they must ensure that they work safely and effectively within their scope of practice and the legal boundaries of their profession, and where they undertake the same aspects of care as an RN they must meet the same standards.3 4 Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and England have differing health services, however the principles of competent staff delivering care to patients are a principle we share within the whole of the UK.5–8

There is no one single framework to guide decision-making on the numbers of staff required to deliver patient care within the endoscopy departments.

The key factors to consider are:

Patients’ health status.

The complexity of the endoscopic procedure to be performed.

Skills and competence of staff to deliver safe patient care.

-

The type, size and layout of the endoscopy unit.

See figure 1.

Methods

This is a consensus document on the competencies required by healthcare staff to deliver adult endoscopy services throughout the UK. The group included nurse representatives from the British Society of Gastroenterology Nurse Associates, Royal College of Nursing, and JAG for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy; medical representatives from the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG); and multidisciplinary representatives from the Welsh Association for Gastroenterology and Endoscopy (WAGE), Scottish Society of Gastroenterology, and Ulster Society of Gastroenterology. The discussions took place via six face-to-face discussions and email. The document was also reviewed by the BSG Clinical Services and Standards Committee prior to publication. The group addressed issues of considerable complexity across four nations to reach consensus. This document is scheduled for review after 5 years, or sooner if major relevant changes to legislation or practice occur.

Recommendations

Consensus was unanimous for all recommendations.

1. We recommend that all registered nursing and allied healthcare professionals work within their code of conduct at all times.

Standards of professional conduct

Registered nursing staff (RN) are responsible for supporting patients through their endoscopy journey, ensuring their privacy, dignity, comfort and safety and directing them to the next steps in their care pathway. It is noted that other allied healthcare professionals are employed within endoscopy units; however, all aspects of patient care from admission to discharge should be supervised by an RN. Registered staff can delegate aspects of patient care to unregistered HCSWs where it is deemed appropriate. All staff whose names appear on a professional register must abide by their code of conduct at all times. Nurses, allied healthcare professionals and HCSWs should be aware of their roles and responsibilities with regard to legislation of medicine management, professional accountability and responsibilities in delegation of tasks.3 9–11

2. We recommend that all patients receive care supervised by an RN who is accountable for their care throughout their time in the endoscopy department.

Staff deployment within the clinical area

Decisions that are made locally about the numbers and levels of staff within the clinical areas must be assessed carefully with consideration given to the following areas:

Review of the clinical skills/competencies of the workforce.

Requirement of drug administration.

Assessment of patient’s individual risk factors.

Risk assessment of the procedures to be performed on any given day.

Risk assessment of diagnostic versus therapeutic procedures.

Risk assessment of potential impact of identified clinical issues.

Environmental placement of staff across the clinical area.

3. We recommend that delegation of responsibilities is considered, and only delegated to an individual deemed competent to undertake the task. All staff competencies should be clearly displayed in the endoscopy unit.

Delegation of patient care

The ability to delegate, assign tasks and supervise is an essential competency for all RNs working in all healthcare settings. All decisions relating to delegation by RNs or midwives must be based on the fundamental principles of safety and public protection.3

Non-registered HCSWs are vital to the delivery of endoscopy services and patient care. They require education, supervision and support to ensure they are competent within their roles and aware of their responsibilities.

The Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) code is clear:

The RN should only delegate tasks and duties that are within that person’s scope of competence, ensuring that they fully understand what is being delegated to them.

Make sure that everyone you delegate tasks to is adequately supervised and supported so they can provide safe and compassionate care.

Confirm that the outcome of any task you have delegated to someone else meets the required standard.

Once a task is delegated to an HCSW they become responsible for their actions and omissions, however the RN retains overall accountability for the management of the patient in their care. It is paramount that all RNs delegating care take this responsibility seriously and make conscious judgements on the appropriateness of the decisions they make. Agency or bank RNs have a professional duty to work within their knowledge and expertise. All staff assisting in endoscopy procedures should have the necessary underpinning knowledge to complete the episode of patient care safely. In accordance with the code, nurses or midwifes must act without delay if they believe a colleague or anyone else may be putting someone at risk.3 10–12

Endoscopy unit managers are responsible for the deployment of staff within the endoscopy unit; they must consider the competence and the level of skill acquisition of staff required, considering both the patient needs and the complexity of the procedure.

Throughout this document we refer to the Skills for Health suite of competencies needed to support patients having an endoscopy procedure. These competencies can be accessed via the Skills for Health website12 (https://tools.skillsforhealth.org.uk) after registration (online supplementary appendix A).

flgastro-2017-100950supp001.docx (143KB, docx)

4. We recommend that thorough assessments of patient health status are undertaken before, during and after endoscopy procedures by a competent registered practitioner (table 1 and figure 1).

A patient’s health status needs to be considered prior to any referral for an endoscopic procedure. The ASA describes a physical status classification system for patients which can be used to assess endoscopy patients (table 1).13 When assessing the risks and benefits for endoscopic procedures, the complexity of the procedure (including sedation and anaesthetic risks), the patient’s health status and their physical ability to cope with the procedures need to be taken into account. A patient undergoing a simple diagnostic endoscopy procedure who has no comorbidity (ASA I) can expect to have a minimal risk of complications. However, a patient who has a history of cardiac disease or respiratory problems (ASA III or IV), for example, will have a higher risk of complications from the procedure and sedation. It is acknowledged that it is difficult to precisely predict when a procedure may escalate from non-complex to complex.

All patients will be assessed before, during and after endoscopic procedures. Where patients are assessed as having greater associated risks from comorbidities they will require higher levels of monitoring to safeguard good outcomes. Consequently, there is a need to triangulate the acuity and dependency of the patient with the needs of the procedure and the staffing competencies required to manage the patient’s care and associated risks.

All patients undergoing an endoscopy procedure will require monitoring of pulse, blood pressure and respiration rates as a minimum before and after procedure. Sedated patients need additional monitoring. Guidance on safe sedation practice for healthcare procedures published by the Academy of Royal Colleges in 2013 outlines these.14 An RN is responsible for the continuous monitoring of the patient’s condition during the procedure with pulse oximetry as a minimum, until the patient is recovered from the effects of both the sedation and the procedure. Where a patient has additional needs, ECG monitoring or capnography should be considered. All staff should have an understanding of how monitoring equipment works, and its limitations, and understand that it does not replace direct observation of the patient.

The RN/practitioner is responsible for observing the patient’s condition, and reporting any concerns to the endoscopist immediately, to enable prompt corrective actions. Some patients will require a general anaesthetic; if this is the case then the anaesthetist is responsible for monitoring the patient and advising on postanaesthetic care.

5. We recommend that staff who assist with complex procedures, or manage the care of patients with complex needs, should demonstrate a high level of relevant competence. This should be both in the technical aspects of endoscopic procedures, and the higher levels of assessment and monitoring required in patients at greater risk of deterioration or complications (tables 1–3).

Procedure risk and complexity

Patients attending endoscopy units vary from those having no identified health problems to patients who are unfit for surgery. The latter patient cohort may, however, have lesions requiring removal using complex procedures such as endoscopic mucosal resection. There are also patients who require emergency life-saving access to endoscopy procedures as in acute gastrointestinal haemorrhage. The National Confidential Enquiry into Patient Outcome and Death enquiry ‘Gastrointestinal Haemorrhage: Time to Get Control (2015)’ highlighted deficiencies in the care for this group of patients.15 Patients’ needs differ, but all patients irrespective of their complexity require competent staff to support them safely through their procedure.

It is generally the responsible clinician’s duty to explain the risks and benefits of the procedure to patients. However, it is often endoscopy nursing staff who identify patients’ concerns about their procedures, or who have concerns about psychological, physical and social aspects of care requiring action prior to discharging the patient home, for example, responsible adult at home, specialist nurse advice.11 16 17

A patient’s health status could have altered from the time of referral to the date of admission for their procedure; it is the duty of the assessing nurse to escalate any concerns regarding patients’ health and fitness for procedure.

We have devised a ‘traffic light’ system to group procedures by complexity into low, medium and high risks; the combination of skills and competencies needed by staff to support the delivery of safe patient care becomes evident (table 2). All areas of the patient pathway are equally important from admission, periprocedure, postprocedure, recovery and decontamination.

The competencies outlined by Skills for Health (online supplementary appendix A) are almost the same for a simple procedure as they are for a complex procedure.12 Staff assisting with high-risk procedures will be expected to have higher levels of experience, knowledge, skill, competence and critical thinking in dealing with more complex equipment and scenarios and are able to support the endoscopist when complications arise. Experienced staff will have greater situational awareness and be able to anticipate what actions and equipment are needed, and react in a calm and timely manner. Patient monitoring is key to the detection of early complications and the prompt action required to address them.

Benner describes the attributes, skills acquisition (table 3), knowledge and expertise that demonstrate a transition from novice to expert.18 Not all individuals are able to make that transition fully. It is therefore incumbent on the endoscopy unit manager and clinical lead to provide assessments of skills acquisition and feed back to staff.

6. We recommend that preprocedure checklists are undertaken, and all aspects of care throughout the procedure, including any changes in health status, must be documented and reported to the endoscopist.

Documentation

The WHO developed a surgical checklist to reduce errors and improve patient safety, endoscopy units have adapted and implemented a variation on the WHO checklist to reduce errors and improve patient safety.19 20 A preprocedure checklist must be undertaken before the procedure starts to ensure everyone is aware of the patient’s identity, their comorbidities, allergies, the procedure being undertaken, that appropriate consent has been obtained and confirmed, whether sedation is required, what equipment may be needed, and to ensure that each staff member present understands their responsibilities and has been introduced to the patient.

Where there are additional needs identified which are not in place, the procedure should not begin until these are resolved. For example, if a patient is having a low-risk procedure but has comorbidities that make the patient a higher risk for complication, for example, cardiac or respiratory disease, then additional monitoring and more experienced staff may be needed to support the patient.

Further checks are carried out when the procedure is completed, and before the patient leaves the endoscopy room, where the whole team confirms postprocedure monitoring and care. These include pathology samples having been correctly labelled, recorded and processed; documentation of the procedure, drugs administered, therapeutic procedures, patient monitoring and that any complications have been recorded, and care has been completed. This should be undertaken with care if human error is to be avoided, and patient care correctly directed.9 19 20

7. We recommend that all staff have access to education and training, in line with endoscopy national frameworks, to meet professional standards, with regular appraisals of performance and competence to support staff development and professional revalidation.

Endoscopy staff education and training

The endoscopy unit nurse manager and the clinical lead hold key roles and responsibilities for service delivery by ensuring staff remain educated, motivated and deliver appropriate patient care that is up to date and evidence based. They have responsibility for planning staffing levels, and negotiating funding for additional staff and equipment to deliver patient services.

Staff must be supported in their educational development to be able to deliver the required care. Within endoscopy services there will be variability in the roles and competencies of staff. Managers must have insight into these when planning staff training and education. Training needs should be assessed at regular intervals, to ensure the demands for the service can be met safely and staff have confidence and satisfaction in the patient care they provide.21 Where there are causes for concern about performance then these must be highlighted and addressed within the employing organisation’s policies and procedures.

Each of the home nations has their own regulators to ensure care is delivered to national standards. In England, it is the Care Quality Commission, in Scotland the Health Improvement Scotland, in Wales the Health Inspectorate Wales, and in Northern Ireland the Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority.22 23

Within the employing organisation a mentorship and supervision programme for all staff is fundamental to ensure staff are able to gain the appropriate attitude, behaviours, skills and knowledge to support the endoscopy services by developing professional competence and confidence in new areas of practice (NMC code practice).

All staff should expect to be supported with opportunities for education and training within their places of work to deliver care to national standards.3 9 24–26

8. We recommend that all staff actively participate in their own educational and skill development.

Staff competencies

All of the competencies are listed within the Skills for Health website https://tools.skillsforhealth.org.uk.12 This website is a useful resource providing tools to assist in the collection of evidence to support each individual competency, and can be accessed by individuals after registration on the website.

There are stages of competence, and it should be remembered that competence can be gained or lost depending on how often the skill is used and practised. Benner describes the five stages of competence: novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient and expert (table 3).18 Where there is a complex patient or a complex procedure being undertaken there should be a ‘proficient’ or ‘expert’ RN/practitioner present to support the patient and to undertake the technical aspects of complex high-risk procedures. It is for the endoscopy unit manager to assess and decide whether an individual member of the team has achieved and importantly maintained competence in aspects of care they are asked to deliver, and that the individual accepts that they are competent.

Expert nurses/practitioners should support the mentoring and education of new and junior staff within the team. Utilisation of these skills is an essential element to achieving a sustainable workforce, to team-building and as a support mechanism to maintain and improve the education of staff for the benefit of patient care (table 3).

9. We recommend that all staff have a portfolio of competencies reflecting their education and training. This includes assessments of their competencies by senior registered staff, and evidence to support to their learning and revalidation. All endoscopy units must have an education, mentorship and supervision programme for all staff.

Education programmes

There are education programmes in the UK to support the education of the endoscopy workforce. From 1 April 2017, JAG provides access to the Gastrointestinal Endoscopy for Nurses (GIN) Programme for all services within the UK as part of the annual license fee. This developing programme encourages practice development within endoscopy and the opportunity to apply the endoscopy competence framework to assist in delivering evidence-based patient care. GIN also provides educational tools for use at unit level allowing staff to carry out appropriate roles and responsibilities. It supports staff to gain the knowledge and skills to lead and promote a safe and patient-centred, learning culture within their local team, and supports the Global Rating Scale workforce domain.27 28 Interval training courses and remote learning opportunities are also being made available. The programme uses an e-portfolio, which can be linked to NMC revalidation29 to record learning and evidence, for example, reflections, Direct Observation of Procedural Skills (DOPS) forms and learning hours. As this programme is being actively developed during 2017, up-to-date information should be sourced from www.jets.nhs.uk.

The All Wales Endoscopy Nurse Competency Framework (AWENcf) is a central component to all current endoscopy nurses training in Wales and provides a structured approach to ensuring the endoscopy workforce is competent and safe to deliver high-quality care within changing endoscopy service needs. There are specific training programmes: ENDO1 is a foundation-level course, ENDO2 is advanced practice skills and ENDO3 is leadership and management skills for senior nurses at bands 6 and 7. WAGE 2016 courses and the academic modules provided by Swansea and Bangor Universities have been established and well attended. AWENcf also complies with the recommendations set out in the Aligning Nursing Skills Guidelines, an All Wales Governance Framework (2014).30

The Northern Ireland education programme hosted by Queen’s University Belfast for endoscopy staff is a level 3 (120 CATs) short course consisting of three modules assessed by the development of a portfolio and an examination. The course aims to prepare nurses at an advanced level with the knowledge, skills and attitudes to manage and care for patients undergoing endoscopic procedures and surgery. The content includes related anatomy and physiology, pathophysiology, clinical diagnosis, preoperative and postoperative nursing care and evidence-based therapeutic interventions related to a variety of endoscopy procedures. Related legal and professional issues are also covered. A level 2 module, Aspects of Endoscopy (20 CATs), was recently developed to assist those staff with no diploma to access further education with similar content to the short course. Currently these courses are not mandatory.31

Postgraduate nurse education courses are available in other universities within the UK, however. It is acknowledged that nationally there has been a significant reduction in continuing professional development funding and postgraduate nurse education; this has been a cause for concern. It is becoming apparent that for many nurses self-funding of education is a reality.

These education programmes are an important asset to endoscopy services and staff; they assist in the development of a portfolio of evidence to demonstrate competence which assists registered staff in revalidation with the NMC and other professional bodies.9

There are differences within endoscopy services in the UK regarding the skill mix of staff delivering patient care. Some organisations, for example, support the training of unregistered staff to undertake airway management. These are local decisions and the organisation must be able to demonstrate that their staff have the underpinning knowledge to support the care they are providing and can demonstrate competencies to undertake that care to the same standard as that of a competent registered practitioner. Serious consideration should be given to developing unregistered staff undertaking such roles to the level of assistant practitioner. This will necessitate formal education such as that provided by the level 5 diploma for assistant practitioners in healthcare.32

It is by consensus agreement of the authors that, at all times throughout the patient care episode from admission to safe discharge, registered staff are present to supervise practice and ensure care standards are maintained.

10. We recommend that due consideration is given to the endoscopy environment. All areas where patients are cared for must have the appropriate staffing skill mix to support patients’ needs.

Environment

The environments in which endoscopy services are accommodated vary extensively, not only in the number of procedure rooms and facilities to support these but additionally in the layout of the facilities and the patient, equipment and staff flow through the unit. All of which can make a difference to the numbers and skill mix of staff required (table 4).

Table 4.

Endoscopy environment

| QP1—respect and dignity | The endoscopy service shall implement and monitor systems to ensure that the privacy, dignity and security of all patients are respected throughout their contact with the service. |

| QP2—consent process including patient information | The endoscopy service shall implement and monitor systems to ensure that informed patient consent is obtained for each procedure. |

| QP3—patient environment and equipment | The endoscopy service shall ensure that adequate resources are provided and used effectively to provide a safe, efficient, comfortable and accessible service. This is achieved through appropriate patient-centred facilities (rooms and equipment). |

| QP5—productivity and planning | The endoscopy service shall ensure that resources and capacity are used effectively to provide a safe, efficient service. This is supported by sound business planning principles within the service. |

In order to achieve JAG accreditation units are required to fulfil core standards to demonstrate the quality of the patient procedure which include environmental standards necessitating appropriate staffing levels. It is therefore important that the environment in which endoscopy takes place is considered when looking at staffing levels. There is a JAG standard requiring evidence of a workforce skill mix review and impact assessment on at least an annual basis or whenever changes to the service, including environmental changes, are anticipated.33

JAG standards to consider when staffing units:

Depending on the devolved nation there is an obligation to meet the requirements of gender segregation and the provision of adequate resources to ensure a safe and accessible service.34 Meeting this requirement may well increase the footfall of staff across the unit to support a segregated patient pathway and flow, and in England the requirement for segregated recovery areas will require additional staffing to support both areas to achieve safe recovery and discharge. The requirement for additional spaces, such as a quiet room for private clinical discussion, will also mean considering the availability of staff to cover the use of these areas as required at all times. Where nurse-led consent is in place there is a need to consider the staff required to undertake this role.

11. We recommend that managers consider the numbers of staff, their qualifications, skill mix and competencies. There must be registered staff responsible for the supervision and direction of appropriate care at each step of the patient journey (figure 1).

Staff supporting service delivery

Clerical roles

Clerical staff are often the first interaction between the endoscopy department and the patient. This could be by telephone or a face-to-face interaction. It is vital that this is a positive experience for the patients that they feel listened to and that consideration of their concerns regarding the timing and nature of the procedure is given. Administration staff require good people skills, a good telephone manner, sound organisational skills, an understanding of waiting list management systems and the knowledge to ensure that all patients have equitable access to their endoscopy procedure. Administration staff are not qualified to give advice about medical or nursing matters, but can direct the patient to read the advice sent to the patient and to the appropriate staff to support the patient.

Registered staff

The majority of staff working within endoscopy departments are RNs. There are also other allied healthcare professionals such as ODPs and radiographers. This group of staff has a registered professional body, a code of conduct, and they are professionally responsible for the care of patients.

Healthcare support workers

This group of staff undertakes routine tasks delegated and supervised by registered staff. This can include: decontamination of endoscopic equipment, meeting and greeting of patients, setting up rooms, stocking cupboards, checking equipment, general cleaning, cleaning and making up trolleys, making drinks for patients, general housekeeping tasks, making appointments, supporting RNs in the recovery area and with other delegated aspects of care dependent on competence. This allows nursing staff to focus on the more complex aspects of patient care. This group of staff has a code of conduct and a minimum set of training requirements in order to provide basic care.35–37 There is opportunity for HCSWs to expand their roles and obtain clinical competencies with additional training and assessment to meet the same standard and quality of care; these more advance skills should be reflected within their job descriptions.

There are codes of conduct for HCSW in Wales, Scotland and England.35–37 In Northern Ireland these are being considered.38

Decontamination technicians

Decontamination services are increasingly becoming centralised and under the control of central sterile services. However, there are many decontamination services still within the endoscopy environment and management structure employing technicians from all backgrounds.

Wherever the service is situated and whoever manages it, the Regulating Medicines and Medical Devices Agency (MHRA)39 states that: ‘All relevant members of staff have been fully trained in decontamination protocols’ (p 47). As recommended within the document, the Institute of Decontamination Sciences has endorsed a number of accredited training courses for technicians and has developed generic job templates along with national profiles, from which job descriptions for endoscopy technicians can be developed. These can be found on the institute’s website at http://www.idsc-uk.co.uk, following the link on the tab to the education section.

It is envisaged that over time this will bring endoscopy technicians into the same group as the Healthcare Science staff groups that work within sterile and decontamination services, with the support and networking that this will provide to ensure that staffing levels and training within this vital area are both safe and effective.

DOPS, specifically for decontamination technicians, is now being developed in partnership with the manufacturers of endoscopes and decontamination equipment. These cover both manufacturer training and ongoing competence assessments and are available on the decontamination page of the BSG website.40

12. We recommend that service managers, endoscopy nursing leads and clinical leads are responsible for planning future service delivery collaboratively. This should include workforce requirements to meet national guidance and local requirements.

Tools to support workforce planning

Workforce planning is expected to support a number of objectives in the delivery of patient care, not only with consideration to aligning the increasing demands and complexities of an endoscopy service with a supply of staff with the appropriate skills, it also needs to work within the resource constraints of the National Health Service.

There is a paucity of evidence-based tools with which to calculate staffing levels in endoscopy. Tools such as the ‘Safer Nursing Care Tool’41 used widely to calculate optimal staffing levels and skill mix in the inpatient setting necessitates gathering information on levels of acuity and dependency on all patients in addition to infection rates, levels of complaints, pressure ulcers and falls. In the outpatient setting of endoscopy, the acuity and dependency of patients varies on a daily basis, although it can be broadly categorised according to age, known disability, comorbidities and procedure type (emergency, routine, diagnostic, therapeutic). This information, however, is not always available when planning ahead, and hence the challenge in calculating staffing levels in endoscopy is in guaranteeing that skills, competencies and staffing numbers can support both the routine diagnostic non-dependent patient procedure and the emergency therapeutic-dependent patient procedure at all times.

The Endoscopy Resource planning tool is available for download on the Tract website (registration is required to access the tool), it was developed by an endoscopy nurse manager. The broad principles of this tool allow services to explore and define what is staffing is required to fit the demand from services; the skills and layout of the endoscopy unit and consider staffing work patterns; taking into considerations such as study leave, sick leave and annual leave. Ian Fretwell, the nurse who developed the tool, explains how to use the tool in a video. This tool describes band 2, 3 and 4 staff as nurses whereas within this consensus agreement these staff bands are defined as HCSWs as they are not RNs.42

Other endoscopy planning tools have been available including:

The productivity and planning assessment tools developed and hosted by JAG.

Workforce capacity planning and Christmas tree template developed in collaboration with National Endoscopy training programme.

The CROMES toolkit associated with Consultant Rota On-call modelling or endoscopy services.

The above tools are currently unavailable at the time of publishing.

Conclusion

There is no one size fits all in regard to staffing levels; we have signposted the processes needed to inform safe staffing levels for endoscopy services. Consideration of the patient health status, the complexity of the procedure to be undertaken, the competencies of staff to care for the patient and support the technical aspects of the endoscopy procedure alongside the layout of the endoscopy unit and legal aspects in medicine management will all need to be considered before a decision on staffing levels is made. However, it is fundamental that an RN has overall responsibility for the standards of patient care and the safety of the patient.

Providers of endoscopy services need to ensure patients are being cared for in a safe manner and to national standards. Registered healthcare professionals have a duty to uphold the values and codes of practice of their registered body, supporting the education and development of junior staff.

Where unregistered HCSWs undertake delegated aspects of care or duties there is a responsibility for the organisation, registered staff and support staff to ensure only those with the appropriate competencies undertake patient care. All staff should have demonstrable competency for the care they provide, documented within a portfolio of evidence validated at least annually through the appraisal process.

It is for endoscopy units and departments to use the resources available to inform the decisions they make with regard to numbers, types and competencies of staff. It remains the responsibility of the endoscopy unit manager and registered nursing workforce to ensure patient care is not compromised.

The competencies outlined in the Skills for Health suite for endoscopy together with the GIN and WAGE and Northern Ireland education programmes facilitate staff education and training.

JAG specifies the framework and standards required to provide a safe and high-quality endoscopy service. These help providers demonstrate evidence of patient-focused care, delivered in a safe setting with adequate equipment and a trained workforce that meet national standards.

This document identifies the complexity in defining staffing levels to provide each patient with safe, effective and compassionate healthcare. Examples of tools that can be used by endoscopy units to provide evidence that they have the right staff in the right place providing the right care to meet patient needs have been shown.

These tools do not replace the expertise of endoscopy managers who understand their staff capabilities. Endoscopy staff must have access to appropriate education to meet both their development needs and that of the service to ensure the delivery of safe patient care.

All endoscopy staff have a duty and responsibility to acknowledge the limitations of their abilities and to seek support, education and any additional training needed to practice safely and competently.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the British Society of Gastroenterology for its support in production of this consensus document. We acknowledge the contributions of Dr Neil Hawkes and Dr John Green from JAG who reviewed and advised on this document.

Footnotes

Contributors: ID led on the project including convening the working party and arranging consensus discussions. HG, RF, AB, MC, PD, VJ, CR, BS, NT and VW contributed to content and formulated the recommendations. TCT and RG contributed on behalf of the British Society of Gastroenterology, providing content and structure, and reviewed the manuscript. AMV reviewed, edited and submitted the manuscript.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Not required.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1. Royal College of Physicians. Joint advisory group on GI endoscopy. http://www.thejag.org.uk (accessed 20 Oct 2017).

- 2. Axon AT, Bottrill PM, Campbell D. Results of a questionnaire concerning the staffing and administration of endoscopy in England and Wales. Gut 1987;28:1527–30. 10.1136/gut.28.11.1527 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Nursing and Midwifery Council. The CODE Professional standards of practice and behaviour for nurses and midwives. https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards/code (accessed 2 Nov 2017).

- 4. Health and Care Professionals Council. Regulating health, psychological and social work professionals. http://www.hpc-uk.org (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 5. Cummings J. How to ensure the right people, with the right skills, are in the right place at the right time: a guide to nursing, midwifery and care staffing capacity and capability. 2015. http://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/nqb-how-to-guid.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 6. Thomas S, Thomas G, Boyce S. Safe nurse staffing levels (Wales) Bill. 2015. http://www.assembly.wales/laid_documents/pri-ld10028_-_safe_nurse_staffing_levels_(wales)_bill/pri-ld10028-e.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 7. Health Improvement Scotland. Endoscopy: raising standards and effectiveness (ENDORSE) programme. http://www.healthcareimprovementscotland.org/our_work/governance_and_assurance/endoscopy_accreditation/endorse.aspx (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 8. Service Development and Improvement. Public health agency health and social care Northern Ireland. http://www.publichealth.hscni.net/directorate-nursing-and-allied-health-professions/nursing/service-development-and-improvement (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 9. Welcome to Revalidation. Nursing and midwifery council. http://revalidation.nmc.org.uk/welcome-to-revalidation (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 10. Nursing and Midwifery. Nursing and Midwifery council standards for medicine management 2007. https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/standards/nmc-standards-for-medicines-management.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 11. Hutson P. Staffing the endoscopy department: what is the appropriate skill mix? Gastrointestinal Nursing 2011;9:28–33. 10.12968/gasn.2011.9.1.28 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Skills for Health. Skills for health license. https://tools.skillsforhealth.org.uk/competence_search/ (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 13. SAHQ. American society of anesthesiologists. https://wwwsahq.org/resources/clinical-information/asa-physical-status-classification-system (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 14. Academy of Royal Medical Colleges. Safe sedation for healthcare procedures. 2013. https://www.rcoa.ac.uk/system/files/PUB-SafeSedPrac2013.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 17).

- 15. NCEPOD. National Confidential Enquiry into patient outcome and Death. 2015. https://www.ncepod.org.uk/2015report1/downloads/TimeToGetControlSummary.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 16. British Society of Gastroenterology. Safety and sedation during endoscopic procedures. 2001. https://www.bsg.org.uk/pdf_word_docs/sedation.doc (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 17. Everett SM, Griffiths H, Nandasoma U, et al. Guideline for obtaining valid consent for gastrointestinal endoscopy procedures. Gut 2016;65:1585–601. 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-311904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Benner P. Novice to expert: excellence and power in clinical nursing practice commemorative edition: Prentice Hall, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 19. World Health Organisation. Surgical safety checklist checklist. http://www.who.int/patientsafety/safesurgery/checklist/en/ (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 20. Matharoo M, Thomas-Gibson S, Haycock A, et al. Implementation of an endoscopy safety checklist. Frontline Gastroenterol 2014;5:260–5. 10.1136/flgastro-2013-100393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ball J, Pike G. Past Imperfect, future tense: nurses’ employment and morale in 2009. London: RCN, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Health and Safety Executive. Who regulates health and social care. http://www.hse.gov.uk/healthservices/arrangements.htm#a4 (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 23. Care Quality Commission. Guidance about compliance: essential standards of safety and quality. 2011. https://services.cqc.org.uk/sites/default/files/gac_-_dec_2011_update.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 17).

- 24. RCN. Guidance on safe nurse staffing levels in the UK. 2010. http://www.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/353237/003860.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 25. RCN. Safe staffing levels – a national imperative. 2013. http://www.rcn.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0018/541224/004504.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 17).

- 26. Royal College of Physicians. Joint advisory group on GI endoscopy. http://www.thejag.org.uk (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 27. British Society of Gastroenterology. British society of gastroenterology four nations committee. http://www.bsg.org.uk/clinical/four-nations/four-nations.html (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 28. Gastrointestinal endoscopy for nurses. http://www.jets.nhs.uk/gin/ (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 29. Revalidation. Nursing and midwifery council. 2017. https://www.nmc.org.uk/globalassets/sitedocuments/revalidation/how-to-revalidate-booklet.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 30. Pugh W, Collins M, Dodds P. All Wales Endoscopy Nurse Competency Framework 2015. https://www.wage.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/AWENcf-Introduction.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 31. Queens University. Queens university belfast short courses. https://www.qub.ac.uk/schools/SchoolofNursingandMidwifery/Study/ContinuingProfessionalDevelopment/ShortCourses/ (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 32. Miller L, Williams J, Marvell R, et al. Assistant practitioners in the NHS is England. http://www.skillsforhealth.org.uk/index.php?option=com_mtree&task=att_download&link_id=175&cf_id=24 (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 33. Royal College of Physicians. JAG accreditation system. https://www.thejag.org.uk/Default.aspx?PageId=5 (accessed 12 Nov 2018).

- 34. Department of Health. Enhancing privacy and dignity achieving single sex accommodation. 2002. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/enhancing-privacy-and-dignity-achieving-single-sex-accomodation (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 35. NHS Education for Scotland. Supporting induction and safe working for all healthcare support workers. http://www.hcswtoolkit.nes.scot.nhs.uk/hcsw-standards-and-codes/ (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 36. Skills for Health. Standards and code of conduct for healthcare support workers and adult social care workers. Supporting induction and safe working for all healthcare support workers. http://www.skillsforhealth.org.uk/standards/item/217-code-of-conduct (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 37. NHS Education for Scotland. Supporting managers and educators to develop healthcare support worker roles. http://www.hcswtoolkit.nes.scot.nhs.uk (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 38. NIPEC. Northern ireland practice education council 2014. http://www.nipec.hscni.net/previousworkandprojects/provide-advice-guidance-and-information-on-best-practice-and-matters-relating-to-nursing-midwifery/healthcaresupportworker/ (accessed 22 Nov 2107).

- 39. Gov.UK. Managing Medical devices: Guidance for healthcare and social service organisations. MHRA 2014. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/managing-medical-devices (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 40. British Society of Gastroenterology. Guidelines for decontamination of equipment for gastrointestinal endoscopy 2016. http://www.bsg.org.uk/clinical-guidance/general/guidelines-for-decontamination-of-equipment-for-gastrointestinal-endoscopy.html (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 41. The Shelford Group. The Shelford group safer nursing care tool. 2016. http://shelfordgroup.org/library/documents/Shelford_Group_Safety_Care_Nursing_Tool.pdf (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

- 42. Fretwell I. Endoscopy resource planning tool 2016. http://www.tractonline.co.uk/endoscopy-resource-planning-tool.php (accessed 22 Nov 2017).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

flgastro-2017-100950supp001.docx (143KB, docx)