Abstract

Background:

Community-based health insurance (CBHI) has been one of the options of health financing in India for a large number of population from the informal sector constituting about 90% of the total population. The objective of this study was to find out what are the factors which have influenced the beneficiaries to enroll in the schemes and also compared them to a noninsured group.

Methods:

A cross-sectional household survey, on 1639 households, was carried out, which had 1108 insured household and 530 noninsured households with a 2:1 ratio. A multivariate analysis was used to find out the determinants of enrolment.

Results:

The multivariate analysis revealed that household variables such as gender of household head, religion, and family size were determinants of enrolment.

Conclusion:

The sociodemographic characteristics of the households do influence the acceptability of the CBHI schemes.

Keywords: Acceptability, community-based health insurance, determinants

INTRODUCTION

Publically financed health insurance schemes are here to stay with the government of India launching the National Health Protection Scheme. The proposed coverage is definitely a step toward substantially reducing catastrophic health care expenditure. It has been reported that community-based health insurance (CBHI) schemes are inclusive of the lowest socioeconomic status (SES) of both urban and rural population and has increased access to healthcare services for the poor.[1,2,3]

The study was carried out among two CBHI schemes, the Manipal Arogya Suraksha (MAS) which is a social initiative by one of the leading health care and educational group in Karnataka and Sampoorna Suraksha (SS) is a component of a rural development project of a temple trust in the state of Karnataka. The present study was an attempt to look at the factors determining enrolment into two CBHI schemes in the Udupi district of Karnataka.

METHODS

A cross-sectional study was carried out in the Udupi district of Coastal Karnataka. The sample size was determined by considering the probability of households who were enrolled in the CBHI schemes and those likely to have chronically ill members in their family. This was assumed to be 20% on the basis of a previous study.[4] The allocation ratio was 2:1 (enrolled to nonenrolled). A total of 1639 households were surveyed of which the number of households enrolled in either of the schemes surveyed were 1108 and those not enrolled were 530 households. The selection of the areas was based on the cluster distribution followed by the CBHI schemes. The list of beneficiaries in the schemes was obtained from the organization's records and the required sample of households was selected by purposive sampling. For the noninsured (control), the households from the same area that were not enrolled for either of the two CBHI schemes were selected using the area sampling method, since there was no list of household available. Each household was selected as one unit of study, and the head of the household was the principal respondent.

The dependent variable was the insurance status of household, and the household should be enrolled in either of the two CBHI schemes selected for study. The independent variables studied were sociodemographic characteristics; the type of family of household; number of women, adults, children, and elderly in the household; and the average annual household expenditure on health. The type of family were categorized as nuclear families which included only parents and one/two children; extended families which included the parents, grandparents, and one/two children; and the joint families where the parents their children along with their families lived together as one household. The SES was scored using modified Udai Pareekh SES scale, which was used to categorize the households on the basis of their SES.[5]

Data management and statistical analysis

A univariate analysis was carried out using Chi-square test for association, to ascertain whether the independent variables as per the hypothesis were significant determinants of acceptability of CBHI schemes. The significant variables were subjected to a multivariate analysis. This was done using a binary logistic regression analysis to find out the determinants of enrolment. The variables that were included in the multivariate analysis included the gender of household head, religion, and number of adults, women and the type of the family, and the average annual expenditure on health care.

RESULTS

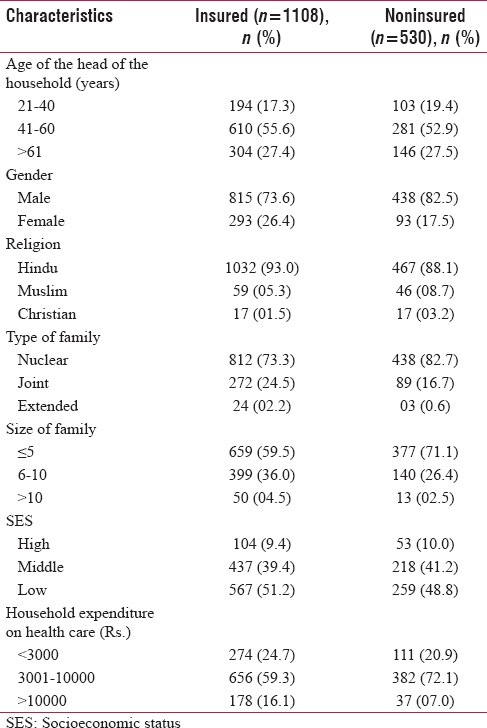

The majority of the respondents were in the age group of 41–60 years across the groups. About 50% of the households across the groups belonged to the low SES. Most of the households spend between Rs. 3000 and Rs. 10,000 as annual household expenditure on health care. Table 1 depicts the baseline sociodemographic characteristics of the households which included the insured (who were enrolled in either of the CBHI schemes) and those not enrolled in any of the schemes.

Table 1.

Baseline sociodemographic characteristics of the surveyed households

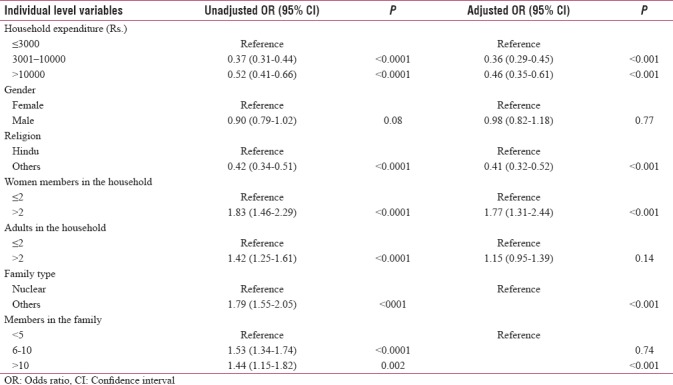

The results of the multivariate analysis are depicted in Table 2. The households where female members were heading the family were more likely to take up insurance as compared to their male counterparts. The average annual expenditure on health care of less than or equal to Rs. 3000 had taken up the CBHI schemes as compared to those who had spent more. The likelihood of people from other religions which included the Muslims, Christians, and Jains were less than the Hindus in taking up the CBHI as per the multivariate analysis.

Table 2.

Determinants of acceptability of community-based health insurance schemes (results of univariate and multiple logistic regression analysis of household-level variables)

DISCUSSION

The characteristics of households and their decision to enroll were determined by their average household expenditure, religion, family size, gender of the household head, and number of women and adult household members as per the findings of the multivariate analysis. The households who were spending an average of Rs. 3000/year or less than that on health had taken up the CBHI schemes. There were other studies which also reported similar findings.[6,7] Some studies reported that occupation and level of education were the determinants,[8] but the current study did not find any association of these two factors with enrolment. Whenever the household head was a female, the likelihood of that household to enroll for insurance was more than a male-headed household. The reason could be that the women had a major stake in managing household finances and particularly in this part of the state the traditional system of matriarchal society norms (Matriarchy refers to a gynocentric form of society, in which the leading role is taken by the women and especially by the mothers of a community), being still prevalent among some of the predominant castes of this region.[9] This trend of women taking the lead in protecting their household against catastrophic medical expenses had also been reported in another study.[1]

The majority of the population in the study area were Hindus, and the likelihood of them taking up the CBHI schemes was higher. There were similar reports in other studies stating that ethnicity and religion do influence decision to enroll for a CBHI scheme.[6,7]

Another important finding was that of households with more than two adults and two women had enrolled more when compared to less than or equal to two in each of the groups. This might be attributed to the fact that enrolling more members would mean a higher premium, but restrictions on maximum coverage were in place for both the CBHI schemes, as a maximum of Rs. 30,000 and Rs. 25,000 for MAS and SS, respectively. This finding had contradicted the finding of studies conducted elsewhere which stated that enrolment in CBHI was more with household having more members.[7,10] The enrolling of households was a policy decision for most CBHI schemes as in the case of these two which were selected for the study, and it was not for an individual, and this would have to a great extent reduced adverse selection which would have been likely if it was allowed to selectively have membership for few household members. This avoided the inclusion of the most likely members, the elderly and the children for the scheme, which would have led to less-risk sharing, as reported in another study.[11,12]

The existing literature on CBHI schemes in India has mostly looked into the functioning of the schemes but has not specifically addressed the issue of what might have been the reasons for voluntary take up of these types of health insurance schemes.[11,13] A limitation of the study was regarding the data on income of the households.

CONCLUSION

The study concluded that factors such as household size, religion, household expenditure on health, individual characteristics such as occupation, literacy status, and marital status were important determinants to acceptability of enrolling in a CBHI.

Financial support and sponsorship

The study was supported by Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR); grant no.: P-57 SBR/ADHOC/4/2010-11. We wish to acknowledge the support provided by the ICMR.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The study was supported by Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR); grant no.: P-57 SBR/ADHOC/4/2010-11. We wish to acknowledge the support provided by the ICMR. The authors wish to acknowledge the study participants who voluntarily participated in the study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ranson MK, Sinha T, Chatterjee M, Gandhi F, Jayswal R, Patel F, et al. Equitable utilisation of Indian community based health insurance scheme among its rural membership: Cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2007;334:1309. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39192.719583.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Devadasan N, Criel B, Van Damme W, Ranson K, Van der Stuyft P. Indian community health insurance schemes provide partial protection against catastrophic health expenditure. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7:43. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-7-43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carrin G. Cluster “Evidence and Information for Policy” (EIP) Geneva: World Health Organization; 2003. Community Based Health Insurance Schemes in Developing Countries: Facts, Problems and Perspectives: Discussion Paper No. 1. Department “Health System Financing, Expenditure and Resource Allocation” (FER) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jütting JP. Do community-based health insurance schemes improve poor people's access to health care? Evidence from rural Senegal. World Dev. 2004;32:273–88. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Supakankunti S. Future prospects of voluntary health insurance in Thailand. Health Policy Plann. 2000;15:85–94. doi: 10.1093/heapol/15.1.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Allegri M, Pokhrel S, Becher H, Dong H, Mansmann U, Kouyaté B, et al. Step-wedge cluster-randomised community-based trials: An application to the study of the impact of community health insurance. Health Res Policy Syst. 2008;6:10. doi: 10.1186/1478-4505-6-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Udai Pareekh GT. Manual of Socio-Ecnomic Status(Rural) New Delhi: Manasayan; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baloul I, Dahlui M. Determinants of health insurance enrolment in Sudan: Evidence from Health Utilisation and Expenditure Household Survey 2009. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(Suppl 2):17. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Suchitra JY, Swaminathan H. The Gender Asset Gap Project Working Paper Series No. 3. Center for Public Policy Research. Bangalore: Indian Institute of Management; 2010. Asset Acquisition among Matrilineal and Patrilineal Communities: A Case Study of Coastal Karnataka. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Panda P, Chakraborty A, Dror DM, Bedi AS. Enrolment in community-based health insurance schemes in rural Bihar and Uttar Pradesh, India. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29:960–74. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czt077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Atim C. Social movements and health insurance: A critical evaluation of voluntary, non-profit insurance schemes with case studies from Ghana and Cameroon. Soc Sci Med. 1999;48:881–96. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00390-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parmar D, Souares A, de Allegri M, Savadogo G, Sauerborn R. Adverse selection in a community-based health insurance scheme in rural Africa: Implications for introducing targeted subsidies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:181. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhageerathy R, Nair S, Bhaskaran U. A systematic review of community based health insurance programs in South Asia. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2017;32:e218–31. doi: 10.1002/hpm.2371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]