Abstract

The CRISPR-CRISPR-associated (Cas) nuclease system offers the ability to perform unprecedented functional genetic experiments and the promise of therapy for a variety of genetic disorders. The understanding of factors contributing to CRISPR targeting efficacy and specificity continues to evolve. As CRISPR systems rely on Watson–Crick base pairing to ultimately mediate genomic cleavage, it logically follows that genetic variation would affect CRISPR targeting by increasing or decreasing sequence homology at on-target and off-target sites or by altering protospacer adjacent motifs. Numerous efforts have been made to document the extent of human genetic variation, which can serve as resources to understand and mitigate the effect of genetic variation on CRISPR targeting. Here, we review efforts to elucidate the effect of human genetic variation on CRISPR targeting at on-target and off-target sites with considerations for laboratory experiments and clinical translation of CRISPR-based therapies.

Human Genetic Variation

Recent large-scale studies have sought to catalog human genetic variation. This includes the initial sequencing of the human genome1,2 and subsequent single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) profiling3 and sequencing of individual genomes.4,5 Structural variation has also been recognized as a widespread source of genomic variability.6,7 These efforts and others have led to the creation of numerous databases of human genetic variation, such as dbSNP,8 dbVar,9 Database of Genomic Variants archive,9 the Database of Genetic Variants,10 the International HapMap Project,11 the exome sequencing project (ESP),12 the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC),13 gnomAD,13 and the 1000 Genomes Project14 (Table 1).

Table 1.

Databases cataloging human genetic variation

| Database | Data contents | Website | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| dbSNP | National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) database of SNPs derived from a variety of sources/studies | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/projects/SNP | 8 |

| dbVar | NCBI database of structural variants derived from a variety of sources/studies | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/dbvar | 9 |

| Database of Genomic Variants archive | European Bioinformatics Institute (EBI) database of structural variants derived from a variety of sources/studies | https://www.ebi.ac.uk/dgva | 9 |

| Database of Genetic Variants | Database of structural variants from control individuals from a variety of worldwide populations | http://dgv.tcag.ca | 10 |

| International HapMap Project | Database of SNPs from 270 individuals from four populations | https://www.genome.gov/10001688/international-hapmap-project | 11 |

| Exome Sequencing Project (ESP) | Whole-exome sequencing from >2000 unrelated African Americans and >4000 unrelated European American individuals | http://evs.gs.washington.edu/EVS/ | 12 |

| Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC) | Database aggregating exome sequencing data. The database consists of >60,000 whole exome sequences from unrelated individuals | http://exac.broadinstitute.org | 13 |

| gnomAD | Database aggregating exome and genome sequencing data. The database consists of >120,000 exomes and >15,000 whole genome sequences. | http://gnomad.broadinstitute.org | 13 |

| 1000 Genomes Project | Reconstructed genomes from 2504 individuals from 26 populations including SNPs and structural variants | http://www.internationalgenome.org | 14 |

| UCSC Genome Browser | Annotated genome browser | https://genome.ucsc.edu | 16 |

| Ensembl Genome Browser | Annotated genome browser | https://ensembl.org | 17 |

| ClinVar | Database of relationships between human variation and phenotypes | https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/clinvar | 18 |

| Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM) | Comprehensive catalog of human genes and genetic phenotypes | https://www.omim.org | 19 |

| Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia (CCLE) | Gene expression, chromosomal copy number, and massively parallel sequencing data from 947 human cancer cell lines | https://portals.broadinstitute.org/ccle | 20 |

| International Cancer Genome Consortium | Comprehensive genomic, transcriptomic, and epigenomic analysis for a variety of tumor types | http://icgc.org | 21 |

| Catalog of Somatic Mutations in Cancer | Cancer-associated somatic mutation information from expert manual curation data and systematic screen data | http://cancer.sanger.ac.uk/cosmic | 22 |

SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism.

Human genetic variation continues to be explored at a rapid pace. Therefore, variant and sequencing databases will continue to increase in the future with examples such as the 100,000 Genomes Project.15 The reference human genome as well as the reference genome for a variety of other organisms can be easily visualized with the ability to simultaneously view databases of genetic variation.16,17 Notably, variant databases have also extended to human disease, such as ClinVar,18 Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man,19 the Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia,20 the International Cancer Genome Consortium,21 and the Catalog of Somatic Mutations in Cancer22 (Table 1).

Extensive efforts have identified significant variation in protein-coding sequences.12,13 For example, the 60,706 human exomes included in the ExAC database identified a variant in exome sequence once in every 8 bp. Furthermore, this work noted that 7.9% of protein-coding variants were multiallelic. Notably, the majority of variants identified in protein-coding sequences were rare (minor allele frequency [MAF] <0.1%).13

Genetic variation is also known to extend beyond the coding genome. The 1000 Genomes Project database, which comprises 2504 sequenced individuals, identified 4.1–5.0 million sites that differed from the reference genome in a given individual, with the vast majority determined to be common variants and only 1%–4% identified as rare (defined as <0.5% MAF). The 1000 Genomes data set overall contains ∼8 million autosomal variants with a frequency >5%, ∼12 million variants with a frequency between 0.5% and 5%, and ∼64 million variants with a frequency <0.5%.14

Structural variation, alterations in DNA content including deletions, insertions, inversions, translocations, and copy number changes, was also detected within individual genomes. Each individual within the 1000 Genomes database had 2100–2500 structural variants on average per genome, which included ∼1000 large deletions, ∼160 copy number variants, ∼915 Alu insertions, ∼128 L1 insertions, ∼51 SINE/VNTR/Alu (SVA) insertions, ∼4 nuclear mitochondrial DNA segments, and ∼10 inversions per genome.14

Genetic diversity is apparent among individuals, but it is also apparent at a population level. Frequency of protein-coding variants has been shown to vary by population.12 In addition, the median number of SNPs was also noted to vary by population within the 1000 Genomes database.14 Structural variation has similarly been found to vary by population with most structural variants being rare (variant allele frequency [VAF] <0.2%). Interestingly, although rare structural variants were typically unique to a given population, common structural variants (≥2.0% VAF) were typically shared across all populations.7 Individuals of African ancestry were found to be the most heterogeneous for both SNPs and structural variants, which is consistent with the Out-of-Africa dispersion model.7,12,14,23

The Effect of Genetic Variation on CRISPR Targeting

The CRISPR*-CRISPR-associated (Cas) nuclease system is a widely utilized platform for genome engineering.24–26 CRISPRs, along other nucleases such as zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) or transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs), have offered the ability for unprecedented functional genetic studies in the laboratory setting as well as the potential for therapy of a variety of genetic diseases.27 CRISPR nucleases rely on Watson–Crick base pairing of a guide RNA (gRNA) with a cognate genomic DNA sequence upstream or downstream of a protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) that is recognized by the nuclease.24–26

The most widely used nuclease is currently the Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 (SpCas9), which recognizes a 5′-NGG-3′ PAM sequence. However, PAM sequence preferences can differ across Cas9 orthologs derived from various bacteria: Staphylococcus aureus (PAM: 5′-NNGRRT-3′), Staphylococcus thermophilus ST1 (PAM: 5′-NNAGAA-3′), S. thermophilus A (PAM: 5′-NGGNG-3′), Neisseria meningitidis (PAM: 5′-NNNNGATT-3′), Campylobacter jejuni (PAM: 5′-NNNNRYAC-3′), and Bacillus laterosporus (PAM: 5′-NNNNCNDD-3′).28

Directed evolution and/or structure-guided mutagenesis have also been used to derive novel PAM sequences from previously identified Cas9 species, such as the SpCas9-VQR and SpCas9-VRER variants with 5′-NGA-3′ PAM and 5′-NGCG-3′ PAM specificities, respectively.29 Finally, other CRISPR nucleases have been identified, such as Cpf1 (Cas12a) with a 5′-TTTV-3′ PAM specificity.30

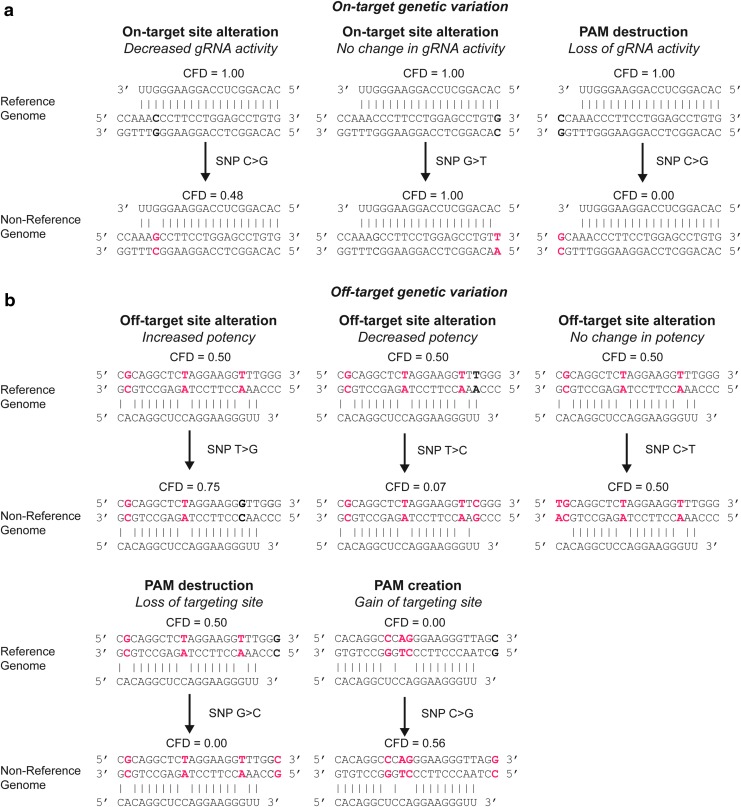

Given the inherent sequence dependence of CRISPR targeting, it logically follows that genetic sequence variants would have the potential to alter both on-target sequences (i.e., a gRNA's cognate genomic sequence) and putative off-target sequences (i.e., sites with sequence homology to the gRNA's intended cognate genomic sequence) (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Alteration of on-target and off-target sites by variants. (a) On-target variation resulting in gRNA activity attenuation or complete loss of gRNA activity as assessed by CFD scores.41 Genomic sequences with mismatches to the gRNA are highlighted in red. Bolded bases indicate bases that are altered in the corresponding reference or nonreference genome. Vertical lines indicate bonds between the gRNA and the cognate homologous sequence at the on-target site. (b) Off-target variation resulting in alteration of the potency of off-target sites as well as PAM creation or PAM destruction as assessed by CFD scores.41 Genomic sequences with mismatches to the gRNA are highlighted in red. Bolded bases indicate bases that are altered in the corresponding reference or nonreference genome. Vertical lines indicate bonds between the gRNA and the cognate homologous sequence at off-target sites. CFD, cutting frequency determination; gRNA, guide RNA; PAM, protospacer adjacent motif.

CRISPR genome editing experiments traditionally utilize gRNAs designed to target sequences present in the reference genome, which can affect CRISPR experiments in a number of ways: (1) Sequence variants can attenuate nuclease activity due to alteration of on-target sites by creating mismatches between the gRNA and the on-target genomic site (Fig. 1a). Moreover, a decrease of nuclease activity can occur due to PAM alteration by sequence variants. For example, if considering the S. pyogenes-derived Cas9 (SpCas9) nuclease with a 5′-NGG-3′ PAM sequence, a SNP can alter genomic sequence from 5′-NGG-3′ to 5′-NHG-3′ or 5′-NGH-3′ sequence to destroy a PAM (termed “PAM destruction”) (H = A, C, or T).

(2) Off-target sites can be altered by sequence variants by increasing or decreasing the number of mismatches between the gRNA and the putative off-target site (Fig. 1b). In addition, sequence variants can also alter PAM sequences at off-target sites. For example, with SpCas9, a SNP can alter genomic sequence from 5′-NHG-3′ or 5′-NGH-3′ to 5′-NGG-3′ sequence to create a novel PAM sequence (termed “PAM creation”). Although the focus of PAM alteration for on-target sites is primarily PAM mutation/destruction, off-target sites are susceptible to both PAM mutation/destruction (with decreased activity at an off-target site) and PAM creation (with gain of activity at an off-target site) due to sequence variants (Fig. 1).

(3) Sequence variants can confound enumeration of CRISPR-engendered mutations at on-target or off-targets sites if appropriate controls are lacking.31 For example, when profiling edits by sequencing and using a standard reference genome, endogenous sequence variants specific to an individual genome may be misclassified as CRISPR-induced mutations. (4) Structural variants, such as changes in copy number, can lead to cellular toxicity.32–34 In fact, it has been observed that increased copy number can result in numerous genomic cleavages, which can directly influence cell survival or proliferation independent of the potential functional importance of the targeted region.

Here, we review the impact of sequence variants on CRISPRs on- and off-targeting specificity for both laboratory experiments and for clinical translation of CRISPR-based therapy. In addition, we review strategies and methodologies to minimize the effects of genetic variation on CRISPR targeting in both contexts.

The Effect of Genetic Variation on gRNA Activity at On-target Sites

Sequence variants may be present at gRNA on-target sites,35–37 which typically results in a reduction of gRNA activity although some mismatches may be well tolerated (maintain equivalent or result in higher gRNA activity)38–43 (Fig. 1a). It is also conceivable for variants to increase gRNA activity, possibly by affecting flanking sequences.40,44 The effect of a mismatch between the genome and gRNA sequence is positional with the magnitude of gRNA activity loss relating to mismatch position within the gRNA sequence.38–41 Alterations in the seed sequence, the 5–12 bp adjacent to the PAM sequence,45,46 generally tend to have a more profound effect on gRNA activity, whereas alterations distant from the PAM sequence tend to have a lesser impact on gRNA activity or even no effect at all.

Several studies have examined the positional effects of mismatches between the genome and gRNAs to quantitate the effect of mismatches for all nucleotides at each gRNA position,38–41 such as the cutting frequency determination (CFD)41 or the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) specificity score.38,39 These scores are typically used in the context of evaluating off-target loci; however, mismatches due to variants at the on-target site can be analyzed in a manner analogous to an off-target site. Variants can also alter the PAM sequence at the on-target site, leading to substantial reductions or no gRNA activity at this locus (Fig. 1a).

A recent study utilized the ExAC database containing >60,000 exomes to examine the effect of variants on targeting protein-coding sequences using five different CRISPR nucleases (SpCas9 with 5′-NGG-3′ PAM sequence; SpCas9-VQR with 5′-NGA-3′ PAM sequence; SpCas9-VRER with 5′-NGCG-3′ PAM sequence; SaCas9 with 5′-NNGRRT-3′ PAM sequence; and AsCas12a with 5′-TTTV-3′ PAM sequence). This study demonstrated that 21%–35% of exome targets using these five nucleases contained a sequence variant in the ExAC database that altered one of these PAM sequences. The 5′-NGCG-3′ PAM for SpCas9-VRER was a notable outlier, containing these PAM-altering variants in 80% of exome targets.36 The propensity for variants to alter the 5′-NGCG-3′ PAM sequence was attributed to its containing a CpG motif, which is known to harbor a high degree of sequence variability.13

In general, this analysis found that 93%–95% of exome targets for the five nucleases examined contained sequence variants predicted to attenuate gRNA activity. However, analysis of a set of 12 therapeutically implicated target genes demonstrated that ∼2/3 (50.6%–91.2%) of all exon-targeted gRNAs had ExAC variants altering the on-target site with a variant frequency of <0.01%. This suggested that gRNAs could be identified that had a low probability of being influenced by genetic variation. Notably, highly variable targets and targets with low variation differed across exonic sequence for a given gene and often clustered together (i.e., highly variable gRNAs clustered in exonic sequence).36

Another study utilized variants from the ∼2500 individuals within the 1000 Genomes Project database to investigate the effect of variants at on-target sites. Using a set of gRNAs targeting 23 human-genome therapeutic targets with MIT specificity scores38,39 ≥80%, this study observed that ∼55% of gRNAs contained variants (SNPs or indels) at their respective on-target sites. Notably, 16.3% of gRNAs evaluated in this study had at least one haplotype that resulted in a predicted complete loss of gRNA activity based on specificity scores (CFD and MIT specificity scores) or the presence of PAM altering variants.

It was further determined that ∼15% of gRNAs with SNPs present at their on-target site were predicted to have reduced activity based on specificity scores (CFD and MIT specificity scores) in >50 individuals within the 1000 Genomes database (n = 2504).37 One intriguing region had a haplotype in 39.4% of individuals that abrogated the target site of six gRNAs targeting this locus. This analysis also noted that PAM-altering variants were a common cause of complete loss of gRNA activity. Of note, loss of gRNA activity in this study was determined by computational prediction scores without experimental validation.

On-target site alteration is also important for laboratory experiments. In particular, pooled CRISPR screens (e.g., genome- or exome-wide screens, tiling screens of coding, or noncoding regions) rely on the assumption that all library gRNAs are functional with comparable activities. In fact, substantial heterogeneity in gRNA activity is likely to confound data interpretation. Several strategies can be adopted to minimize the effect of genetic variation at on-target sites.

The first strategy uses sequencing, which can either be targeted sequencing or whole-exome/whole-genome sequencing. If the region of interest is narrow (i.e., a few kilobases or less), it is possible to utilize conventional Sanger sequencing to identify any variants present. If the targeted regions are large or for pooled CRISPR experiments targeting large regions or multiple loci, whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing can be pursued. This may be particularly worthwhile if a given laboratory or project uses a small number of cell lines routinely. Given the cost of whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing at present, it can be difficult to justify the expense for nonimmortalized primary cells for the purposes of identifying variants that may alter the on- or off-target landscape; however, this may become more feasible as the cost of whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing continues to decline in the future.47

After targeted or large-scale (whole-exome or whole-genome) sequencing efforts, variants can be accounted for at the gRNA design stage to ensure perfect matching between gRNA and cognate genomic target sites. Furthermore, an advantage of whole-genome sequencing data is the ability to also use it for the computational identification of genome-specific putative off-target sites (see further discussion hereunder), which is not possible with targeted or local sequencing, although this effort may only provide partial benefit, given limitations with existing computational models for off-target prediction.

If a large region or multiple loci are being targeted using a pooled CRISPR screening approach and whole-exome or whole-genome sequencing cannot be performed, an alternative strategy involves utilization of publicly available databases for “variant-aware” gRNA design.35,48 Several gRNA design tools already offer the ability to account for sequence variants to generate variant-aware gRNAs.35,49 Notably, one recent study utilized haplotype-derived variants from the 1000 Genomes Project database to design gRNAs with a perfect match to the reference genome as well as gRNAs with perfect matches to all the haplotypes present in that database.35

NGG- and NGA-restricted variant-aware pooled gRNA libraries were designed to target all DNase hypersensitive sites within a >300 kb intergenic region in the absence of sequencing information for the region in the cell line utilized. Identified regions harboring functional sequence were subsequently sequenced by the Sanger method to identify any variants with the potential to alter data quality or interpretation. Thus, the variant-aware gRNA design approach allows for the minimization of false negatives due to gRNA activity attenuation, which is particularly useful in large regions or multiple loci experiments in the absence of whole-genome sequencing information.

After subsequent identification of regions of interest, Sanger sequencing of these regions can be performed, assuming the identified regions are relatively narrow to allow for post hoc inclusion or exclusion of reference genome-derived or variant-aware gRNAs from further analysis.35 Of note, this approach of variant-aware gRNA design followed by Sanger sequencing of regions of interest is unable to identify variant-induced alterations at off-target sites.

Recent studies have also demonstrated that structural variants (i.e., copy number variants) or aneuploidy can lead to cellular toxicity, resulting in false positives in pooled CRISPR screens that rely on a dropout (depletion) phenotype.32–34 Cellular toxicity results from the induction of numerous double-strand breaks in a single cell from CRISPR-mediated cleavage of amplified regions (i.e., loci with increased copy number).

A variety of experimental methods are available to assess copy number variation with differing levels of resolution, such as karyotype analysis, fluorescence in situ hybridization, quantitative real time (qRT)-polymerase chain reaction, or copy number quantitation from deep sequencing. In general, there is larger concern for structural variation within cancer-derived cell lines, which may be more prone to develop aneuploidy or copy number variation in the setting of genomic instability; however, structural variation can also be induced in other cell lines particularly if oncogenes are used to impart immortality.

The cytotoxic effect of targeting a region with increased copy number can be mitigated in several ways. The first is to simply exclude gRNAs (before or after an experiment) that target amplified regions as potential sources of false positivity.50 One notable study computationally corrected for variants and copy number across multiple cancer cell lines to enhance data quality and interpretation from pooled CRISPR screens.51

Another study utilized a strategy involving computational correction of copy number through development of a computational method called CERES to estimate gene-dependency accounting for copy number variation for pooled CRISPR screens for essential genes that rely on a dropout phenotype.52 This study analyzed pooled CRISPR screens in 342 cancer cell lines spanning 27 unique lineages, which consistently identified a correlation between copy number and gRNA depletion.

Of note, this type of computational analysis was designed with the capability to analyze data derived from single or multiple cell lines. This study highlighted the ability to utilize computational methods to account for copy number variation to identify true cancer vulnerabilities and minimize false positives associated with copy number variability.52 Finally, it is conceivable to correct copy number alterations. For example, a trisomy may be reduced to disomy through CRISPR-based methods for elimination of an entire chromosome53; however, such methods would not be feasible for larger degrees of variation or more complex copy number variations.

Alteration of the Off-target Landscape by Genetic Variation

Genetic variants can have numerous effects on the off-target landscape for gRNAs. This can include increasing/decreasing the number of mismatches to alter a given off-target site's potency (Fig. 1b). In addition, variants can create or destroy PAMs (and thus create off-target sites or diminish rates of off-target site mutation) (Fig. 1b). Finally, structural variants can eliminate or amplify the number of off-target sites.

In general, the number of computationally predicted off-target sites is influenced by the abundance of potential PAM sequences in the genome. For example, it has been observed that longer PAM sequences typically have reduced genomic abundance.35 As such, gRNAs for CRISPR nucleases with longer PAM sequences tend to have fewer computationally predicted off-target sites, which is likely related to reduced PAM abundance in the genome overall.35,36 However, the relationship between PAM length and experimentally validated off-target sites remains to be elucidated.

An initial study explored a germline intergenic, heterozygous SNP (rs72716547) in human-induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) that converted an off-target site from three to two mismatches relative to the on-target site. Notably, off-target editing at this site was initially identified on the allele with the rs72716547 variant that had two mismatches; however, off-target editing was not detected on the allele with reference sequence (with three mismatches due to the absence of rs72716547).54

The authors sought to further explore this phenomenon of reducing mismatches at off-target sites. Therefore, when considering the genome of the PGP1 cell line (cell line derived from an individual of European descent), the probability that three mismatch off-target sites would be converted into two mismatch off-target sites by variants was ∼1.5% when using >900,000 target sites in the human exome. Interestingly, when considering variants from an individual of African ancestry, the probability of a SNP converting a three mismatch site into a two mismatch site increased to ∼2%,54 which is consistent with increased genetic diversity in African populations as compared with European populations.

Another study analyzed off-target sites for multiple gRNAs across several cell lines to identify genome-specific off-target effects due to variants as assessed by CIRCLE-seq (an unbiased genome-wide method to assay for off-target cleavage sites in vitro).55 This analysis demonstrated that although many off-targets for the same gRNA correlated between the different cell lines examined, there were >50 loci with cell line-to-cell line cleavage variability. In ∼15% of these instances, SNPs likely to alter gRNA activity were identified.

To further analyze the effect of SNPs at off-target sites, the authors utilized the 1000 Genomes Project database to examine for variants at the >1000 detected off-target sites for the gRNAs analyzed. This analysis demonstrated the presence of genetic variation at these sites in ∼2.5% of individuals as well as detected variation at off-target sites when stratifying by population. For the off-target sites analyzed using 1000 Genomes-derived haplotypes, SNPs were noted to increase the number of mismatches in ∼75% of cases (suggestive of decreased off-target site potency), to decrease the number of mismatches in ∼9% of cases (suggestive of increased off-target site potency), and to be unchanged in the number of mismatches in the remaining ∼16% of instances. Notably, CIRCLE-seq offers the ability for reference genome-independent analysis, which is particularly useful for unique genomes.55

To globally assess the effect of genetic variants on the off-target landscape, another study utilized variants from the ∼2500 individuals within the 1000 Genomes Project database to identify the extent of PAM sequence creation or mutation when considering the 5′-NGG-3′ PAM sequence for SpCas9. This analysis identified >10 million sites of PAM creation and >20 million sites of PAM mutation throughout the hg19 genome build.37 The same study also analyzed the effect of SNPs from three data sets (1000 Genomes database, a subset of gnomAD, and a French Canadian cohort) on the global off-target landscape for gRNAs targeting therapeutically important loci.

To perform this analysis, an “ambiguous genome” was created, whereby the genomic position of SNPs was replaced with International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) ambiguity codes to account for multiple alleles (e.g., an A > C SNP would be replaced with the M ambiguity code where M = A or C). This analysis demonstrated an overall decrease in the aggregate specificity scores, suggestive of increased off-target potential for the gRNAs examined. Notably, this largely resulted from an increase in novel lower potency off-target sites (i.e., 2–4 mismatches).

Interestingly, the French Canadian cohort demonstrated the smallest deviation from the reference genome, which is consistent with genetic homogeneity as a founder population. The ambiguous genome analysis also identified a small subset of analyzed gRNAs (∼0.5%) with one predicted perfect match in the reference genome that gained an additional perfect match in the ambiguous genome.37 The ambiguous genome analysis offered an initial assessment of the effects of variants on the off-target landscape; however, it is limited by the inability to discriminate allele frequencies, lack of haplotype consideration, and exclusion of indels.

Therefore, the authors used a haplotype-based approach to analyze gRNAs with MIT specificity scores ≥80%, targeting therapeutically important loci to address the limitations of the ambiguous genome approach. For the gRNAs examined in this haplotype-based approach, novel off-target sites with fewer than three mismatches or fewer than two mismatches were identified for ∼10% of gRNAs or ∼0.5% of gRNAs, respectively, when considering haplotypes from the 1000 Genomes database. Interestingly, novel off-target sites with fewer than three mismatches or fewer than two mismatches were identified for ∼5% of gRNAs or ∼0.5% of gRNAs, respectively, when considering haplotypes from the French Canadian founder population cohort.37

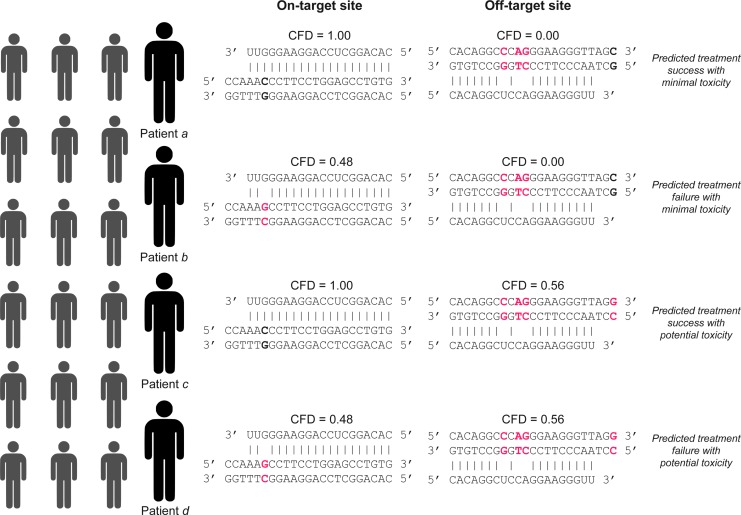

One notable example was a gRNA with 17% of haploid genomes reducing an off-target site with two mismatches to a single mismatch; the single mismatch was not predicted to alter gRNA activity, which suggested a variant-induced creation of a potentially strong off-target site. Another example involved a gRNA with four unique haplotypes that displayed a potential strong off-target site in exon 1 of the KL gene. These four haplotypes also had variants at the associated on-target site predicted to attenuate gRNA activity. This example suggested the possibility of variants reducing on-target gRNA activity and increasing the potency of an off-target site within an individual genome37 (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Hypothetical patient-specific sequences for different individuals seeking CRISPR-based therapeutic genome editing that may be prone to treatment failure and/or adverse outcomes due to genetic variation as assessed by CFD.41 Genomic sequences with mismatches to the gRNA are highlighted in red. Bolded bases indicate bases that are altered in the genome of another patient. Vertical lines indicate bonds between the gRNA and the cognate homologous sequence at on-target or off-target sites.

Interestingly, it was noted that although variants tended to increase off-target potential within haploid genomes, instances were also identified when variants reduced off-target potential.37 In a similar vein, another study noted that the number of off targets increased as the haplotype frequency decreased, suggesting that unique off-target sites for a given gRNA might tend to differ between individuals.36 Finally, indels and other structural variants have also been noted to alter the off-target landscape. One notable example included a potent off-target site that was deleted in 6.9% and duplicated in 0.06% of haploid genomes.37 Taken together, these studies examining the effect of variants on the off-target landscape have suggested that variants can have a significant impact on off-target sites and can also result in the creation of novel off-target sites.

Variant-induced effects on the off-target landscape may be mitigated by CRISPR nucleases with increased specificity (i.e., highly specific nucleases would be less affected by increases in off-target site potency due to variants). Strategies/methodologies to enhance nuclease specificity include truncated gRNAs,56 dimeric FokI nucleases,57,58 double nickase targeting,59,60 high fidelity/enhanced specificity genome editing reagents (SpCas9-HF1/eSpCas9/HypaCas9/evoCas9),61–64 computational off-target prediction scores,49,65 and reduced exposure to genome editing reagents.66–68 Further discussion of methods to enhance specificity is presented in Tycko et al.69

In addition to strategies to enhance specificity, numerous methods have been developed to detect off-target cleavages, including unbiased genome-wide off-target detection methods.43,55,70–75 A practical strategy to control for off-target effects in CRISPR experiments is to use multiple, sequence-independent gRNAs for the same target.76 In this case, a common phenotype is more likely to result from a common on-target effect as opposed to a common off-target effect.

At present, computational prediction of off-target sites relies on sequence only with utilization of sequence homology to identify putative sites. In general, off-target cleavage events have primarily been determined to occur frequently at loci with ≤3 mismatches across different CRISPR nucleases, although validated off-target cleavages have been observed with as many as 6 mismatches.38,42,43,54,70,71,77–80 Therefore, improved computational models to identify and predict off-target sites are needed. Recent studies have identified an uncoupling between Cas9 binding and cleavage.46 Therefore, better prediction methods may benefit from an improved understanding of Cas9 binding versus cleavage.45,81–84 In addition, incorporation of chromatin context into off-target cleavage prediction is likely to be beneficial in the context of living cells.46,85

Genetic Variation at On- and Off-target Sites Can Confound CRISPR-Mediated Indel Enumeration

Numerous computational tools have been created to enumerate CRISPR-mediated indels from Sanger sequencing86,87 or from deep sequencing.31,88–92 Genetic variation can serve as a potential false positive for indel detection when analyzing CRISPR mutagenesis. For example, a SNP or indel present in the genome of a given cell line in proximity to the predicted CRISPR-mediated cleavage site can be incorrectly attributed to CRISPR mutagenesis.93–100 Variant homozygosity is oftentimes apparent given the low probability of the same indel occurring in 100% of analyzed alleles; however, variant heterozygosity can be more difficult to detect as stereotyped indels can occur at a given locus, particularly with microhomology-mediated repair.101,102

Heterogeneous batches of cells (e.g., tumor samples) can present further challenges as the detected allele frequencies will vary not only due to homozygosity versus heterozygosity, but also as a function of clonal frequency; variant phasing could be useful in identifying variants in this context if possible. In all cases, it is essential to sequence a nonedited control, which can take the form of a nontargeting control gRNA (i.e., a gRNA without a perfect match in the genome that is not predicted to produce any genomic cleavages) or simply parental cells. Any “indels” present in the nonedited control can be attributed to either variants present in the cells/samples or sequencing error. The identified variants/indels from the nonedited controls can then be computationally removed from the analysis of the CRISPR mutagenized samples.31

The Inclusion of Human Genetic Variation in the Clinical Development Plan for Therapeutic Genome Editing

Therapeutic genome editing using CRISPR technology holds significant promise for the treatment of a variety of genetic diseases,27,103,104 and CRISPR-based treatments are continuing to move toward the clinic.105,106 The success of CRISPR-based therapies will depend on treatment efficacy as well as treatment safety. A potential challenge for therapeutic genome editing stems from the unique genome encountered by genome-editing reagents for each patient seeking therapy (Fig. 2).

Consideration of genetic variants for therapeutics might be particularly important when targeting loci identified by genome-wide association studies, which could potentially suggest that the region contains common trait-associated variants.35,107,108 For example, one study examined therapeutically relevant gRNAs and identified instances whereby gRNAs could have a favorable off-target profile in the majority of haploid genomes, but also have rare haplotypes with potent off-target sites, which can even occur within genes.37

In addition, repetitive sequences pose a potential issue for therapeutic targeting, which can occur when targeting exonic or noncoding sequences.35,36 At present, effective methods do not exist to target the intended on-target site when multiple other perfect matches exist in the genome; however, it is typically possible to identify alternative gRNAs for the same target gene or locus that have single genomic matches. Given the expanding CRISPR toolkit, it may also be possible to identify gRNAs for alternative nucleases with a single genomic match within a region containing repetitive sequence.35,36

Numerous potential strategies might be adopted to help ensure effective and safe personalized therapy for patients undergoing therapeutic genome editing. One strategy involves utilizing databases to identify regions with lower levels of genetic variation and to avoid high frequency haplotypes.36 Another strategy, although one that would be more aspirational in the long term, might be to carry forward multiple, sequence-independent gRNAs for a given therapeutic target (e.g., designing and testing multiple gRNAs targeted within a narrow region or against different exons of the same gene).

Alternatively, gRNAs using multiple nucleases with independent PAM sequences to target the same region could undergo clinical development, which would increase the number of possible gRNAs for clinical targeting.35–37 It is also conceivable to develop gRNAs intended for therapy for individuals of different ancestry given the possibility of population-specific on- and off-target effects36,37,55; however, population stratification will be limited by de novo variants, which have been estimated at a frequency of 44–82 SNPs per individual.109 It also may not be feasible to develop gRNAs for every potential population.

Once one or more gRNAs are identified, methodologies for unbiased genome-wide off-target detection may offer the best strategies to identify gRNAs with limited off-target potential for clinical translation.43,55,70–74 It may be possible to utilize unbiased genome-wide detection methods in multiple cell lines or primary cells to help identify any variant-induced effects. In particular, it is conceivable to evaluate on- and off-target activity for therapeutic gRNAs using patient-derived iPSCs to account for patient-specific variation; however, this approach may be limited by somatic mosaicism.37 A better understanding of the factors affecting off-target cleavage will be useful to maximize specificity of CRISPR reagents. In the meantime, it is desirable to be conservative and avoid gRNAs that have putative off-target sites within or nearby genes with known important cellular functions (i.e., tumor suppressors).

Ultimately, patient-specific whole-genome sequencing may represent the best method to identify variants that have the potential to alter CRISPR therapeutic targeting and aid in informing gRNA choice; however, cost of sequencing remains a barrier47 as well as subsequent cost for data analysis and storage. It may be possible to utilize whole-genome sequences available for a given population. This strategy may be more useful in founder populations or other populations with limited heterogeneity.37 However, population-based methods are limited by de novo variants. Furthermore, somatic mosaicism has the potential to further complicate therapeutic genome editing by serving as an additional source variation.

Genetic Variation in Nonhuman Experimental Models and Systems

The issue of genetic variation is not uniquely human and extends to all nonhuman experimental models.110 For example, extensive genetic variation has been identified in mouse (Mus musculus),111,112 Drosophila melanogaster,113,114 and Arabidopsis thaliana115 with associated variant databases including the mouse genome database116 and FLYSNPdb.117 It has been previously reported that nuclear, homologous, noncoding sequences will differ 0.3%–0.8% in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. 0.5%–1% in D. melanogaster, 0.1%–0.4% in Caenorhabditis elegans, and 0.1%–0.2% in M. musculus.110

A unique advantage for nonhuman experimental models is the ability to limit the extent of genetic variation through inbreeding although an inbred homogenous population may still differ from the reference genome for the given organism. Therefore, it is important to consider variants in the context of genomic targeting in nonhuman experimental models and systems.

Conclusions

Recent efforts have highlighted the importance of accounting for genetic variation in the design of CRISPR experiments in the laboratory setting as well as during optimization of CRISPR reagents for therapeutic genome editing applications. This, in turn, emphasizes the importance of continued efforts to catalog genetic variation. In addition, these data suggest the utility of establishing a database of whole-genome sequencing for cell lines, which can be used for cell line-specific gRNA design to facilitate CRISPR-based experiments.118

The impact of genetic variation on CRISPR targeting is not unique to CRISPR as it is a concern when using other genome editing technologies such as ZFNs and TALENs. Furthermore, the impact of human genetic variation on therapeutic genome editing is also not unique to genome editing treatment approaches. For example, variation in drug-target genes can influence drug binding119,120 and genetic variants can influence the rate of drug metabolism.121 However, numerous strategies are available to minimize off-target potential to optimize gRNAs for personalized, safer, and more effective therapy for patients.

Taken together, initial efforts to identify the effects of genetic variation on CRISPR targeting have underscored the importance of taking human genetic variation into account in both a laboratory and clinical translation setting. In the therapeutic context, this may help to minimize adverse outcomes to offer nontoxic and efficacious treatments to patients, which will allow for the realization of the potential of CRISPR-based therapies for the treatment of genetic disorders in the future.

Acknowledgments

M.C.C. is supported by a National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK) Award (F30DK103359). L.P. is supported by a National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI) Career Development Award (R00HG008399). J.K.J. and L.P. are supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (HR0011-17-2-0042). J.K.J. is supported by the Desmond and Ann Heathwood Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Research Scholar Award.

Authors' Contributions

M.C.C. reviewed the literature. M.C.C., J.K.J., and L.P. wrote the article. All coauthors have reviewed and approved of the article before submission.

Author Disclosure Statement

M.C.C. and L.P. have no competing financial interests. J.K.J. has financial interests in Beam Therapeutics, Editas Medicine, Monitor Biotechnologies, Pairwise Plants, Poseida Therapeutics, and Transposagen Biopharmaceuticals. J.K.J.'s interests were reviewed and are managed by Massachusetts General Hospital and Partners HealthCare in accordance with their conflict of interest policies.

Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats.

References

- 1.Lander ES, Linton LM, Birren B, et al. Initial sequencing and analysis of the human genome. Nature. 2001;409:860–921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Venter J, Adams M, Myers EW, et al. The sequence of the human genome. Science. 2001;291:1304–1351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.International HapMap Consortium. A haplotype map of the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:1299–1320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy S, Sutton G, Ng PC, et al. The diploid genome sequence of an individual human. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:2113–2144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wheeler DA, Srinivasan M, Egholm M, et al. The complete genome of an individual by massively parallel DNA sequencing. Nature. 2008;452:872–876 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kidd JM, Cooper GM, Donahue WF, et al. Mapping and sequencing of structural variation from eight human genomes. Nature. 2008;453:56–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sudmant PH, Rausch T, Gardner EJ, et al. An integrated map of structural variation in 2,504 human genomes. Nature. 2015;526:75–81 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sherry ST. dbSNP: The NCBI database of genetic variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:308–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lappalainen I, Lopez J, Skipper L, et al. DbVar and DGVa: Public archives for genomic structural variation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;41:936–941 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.MacDonald JR, Ziman R, Yuen RK, et al. The Database of Genomic Variants: A curated collection of structural variation in the human genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 2013;42:D986–D992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.International HapMap Consortium. A second generation human haplotype map of over 3.1 million SNPs. Nature. 2007;449:851–861 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fu W, O'Connor TD, Jun G, et al. Analysis of 6,515 exomes reveals the recent origin of most human protein-coding variants. Nature. 2013;493:216–220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lek M, Karczewski KJ, Minikel EV, et al. Analysis of protein-coding genetic variation in 60,706 humans. Nature. 2016;536:285–291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Auton A, Abecasis GR, Altshuler DM, et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature. 2015;526:68–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peplow M. The 100,000 genomes project. BMJ. 2016;1757:i175–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karolchik D, Barber GP, Casper J, et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: 2014 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:764–770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hubbard T, Barker D, Birney E, et al. The Ensembl genome database project. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:38–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Landrum MJ, Lee JM, Riley GR, et al. ClinVar: Public archive of relationships among sequence variation and human phenotype. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:980–985 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hamosh A, Scott AF, Amberger J, et al. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM): A directory of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002;30:52–55 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barretina J, Caponigro G, Stransky N, et al. The Cancer Cell Line Encyclopedia enables predictive modelling of anticancer drug sensitivity. Nature. 2012;483:603–607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang J, Baran J, Cros A, et al. International cancer genome consortium data portal-a one-stop shop for cancer genomics data. Database. 2011;2011:1–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forbes SA, Beare D, Boutselakis H, et al. COSMIC: Somatic cancer genetics at high-resolution. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D777–D783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gravel S, Henn BM, Gutenkunst RN, et al. Demographic history and rare allele sharing among human populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:11983–11988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mali P, Yang L, Esvelt KM, et al. RNA-guided human genome engineering via Cas9. Science. 2013;339:823–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cong L, Ran FA, Cox D, et al. Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science. 2013;339:819–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komor AC, Badran AH, Liu DR. CRISPR-based technologies for the manipulation of eukaryotic genomes. Cell. 2017;168:20–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cox D, Platt RJ, Zhang F. Therapeutic genome editing: Prospects and challenges. Nat Med. 2015;21:121–131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karvelis T, Gasiunas G, Siksnys V. Harnessing the natural diversity and in vitro evolution of Cas9 to expand the genome editing toolbox. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2017;37:88–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kleinstiver BP, Prew MS, Tsai SQ, et al. Engineered CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with altered PAM specificities. Nature. 2015;523:481–485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zetsche B, Gootenberg JS, Abudayyeh OO, et al. Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell. 2015;163:759–771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pinello L, Canver MC, Hoban MD, et al. Analyzing CRISPR genome-editing experiments with CRISPResso. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:695–697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aguirre AJ, Meyers RM, Weir BA, et al. Genomic copy number dictates a gene-independent cell response to CRISPR-Cas9 targeting. Cancer Discov. 2016;2641:617–632 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Munoz DM, Cassiani PJ, Li L, et al. CRISPR screens provide a comprehensive assessment of cancer vulnerabilities but generate false-positive hits for highly amplified genomic regions. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:900–913 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang T, Birsoy K, Hughes NW, et al. Identification and characterization of essential genes in the human genome. Science. 2015;350:1096–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Canver MC, Lessard S, Pinello L, et al. Variant-aware saturating mutagenesis using multiple Cas9 nucleases identifies regulatory elements at trait-associated loci. Nat Genet. 2017;49:625–634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scott DA, Zhang F. Implications of human genetic variation in CRISPR-based therapeutic genome editing. Nat Med. 2017;23:1095–1101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lessard S, Francioli L, Alfoldi J, et al. Human genetic variation alters CRISPR-Cas9 on- and off-targeting specificity at therapeutically implicated loci. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E11257–E11266 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hsu PD, Scott DA, Weinstein JA, et al. DNA targeting specificity of RNA-guided Cas9 nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:827–832 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanjana NE, Shalem O, Zhang F. Improved vectors and genome-wide libraries for CRISPR screening. Nat Methods. 2014;11:783–784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Doench J, Hartenian E, Graham D, et al. Rational design of highly active sgRNAs for CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene inactivation. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:1262–1267 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doench JG, Fusi N, Sullender M, et al. Optimized sgRNA design to maximize activity and minimize off-target effects of CRISPR-Cas9. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:184–191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fu Y, Foden JA, Khayter C, et al. High-frequency off-target mutagenesis induced by CRISPR-Cas nucleases in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:822–826 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tsai SQ, Zheng Z, Nguyen NT, et al. GUIDE-seq enables genome-wide profiling of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:187–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Liu X, Homma A, Sayadi J, et al. Sequence features associated with the cleavage efficiency of CRISPR/Cas9 system. Sci Rep. 2016;6:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.O'Geen H, Henry IM, Bhakta MS, et al. A genome-wide analysis of Cas9 binding specificity using ChIP-seq and targeted sequence capture. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:3389–3404 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jiang F, Doudna JA. CRISPR-Cas9 structures and mechanisms. Annu Rev Biophys. 2017;46:505–529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wetterstrand K. DNA Sequencing Costs: Data from the NHGRI Genome Sequencing Program (GSP). 2017. www.genome.gov/sequencingcostsdata (last accessed December8, 2017)

- 48.Montalbano A, Canver MC, Sanjana NE. High-throughput approaches to pinpoint function within the noncoding genome. Mol Cell. 2017;68:44–59 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Haeussler M, Schönig K, Eckert H, et al. Evaluation of off-target and on-target scoring algorithms and integration into the guide RNA selection tool CRISPOR. Genome Biol. 2016;17:14–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang T, Yu H, Hughes NW, et al. Gene essentiality profiling reveals gene networks and synthetic lethal interactions with oncogenic Ras. Cell. 2017;168:890–903.e15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rauscher B, Heigwer F, Henkel L, et al. Toward an integrated map of genetic interactions in cancer cells. Mol Syst Biol. 2018;14:e765–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Meyers RM, Bryan JG, Mcfarland JM, et al. Computational correction of copy-number effect improves specificity of CRISPR-Cas9 essentiality screens in cancer cells. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1779–1784 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zuo E, Huo X, Yao X, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated targeted chromosome elimination. Genome Biol. 2017;18:22–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yang L, Grishin D, Wang G, et al. Targeted and genome-wide sequencing reveal single nucleotide variations impacting specificity of Cas9 in human stem cells. Nat Commun. 2014;5:550–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsai SQ, Nguyen NT, Malagon-Lopez J, et al. CIRCLE-seq: A highly sensitive in vitro screen for genome-wide CRISPR-Cas9 nuclease off-targets. Nat Methods. 2017;14:607–614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Fu Y, Sander JD, Reyon D, et al. Improving CRISPR-Cas nuclease specificity using truncated guide RNAs. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:279–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tsai SQ, Wyvekens N, Khayter C, et al. Dimeric CRISPR RNA-guided FokI nucleases for highly specific genome editing. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:569–576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Guilinger JP, Thompson DB, Liu DR. Fusion of catalytically inactive Cas9 to FokI nuclease improves the specificity of genome modification. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:577–582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ran FA, Hsu PD, Lin CY, et al. Double nicking by RNA-guided CRISPR Cas9 for enhanced genome editing specificity. Cell. 2013;154:1380–1389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Mali P, Aach J, Stranges PB, et al. CAS9 transcriptional activators for target specificity screening and paired nickases for cooperative genome engineering. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:833–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kleinstiver BP, Pattanayak V, Prew MS, et al. High-fidelity CRISPR-Cas9 nucleases with no detectable genome-wide off-target effects. Nature. 2016;529:490–495 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Slaymaker IM, Gao L, Zetsche B, et al. Rationally engineered Cas9 nucleases with improved specificity. Science. 2016;351:84–88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Chen JS, Dagdas YS, Kleinstiver BP, et al. Enhanced proofreading governs CRISPR-Cas9 targeting accuracy. Nature. 2017;550:407–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Casini A, Olivieri M, Petris G, et al. A highly specific SpCas9 variant is identified by in vivo screening in yeast. Nat Biotechnol. 2018;36:265–271 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Listgarten J, Weinstein M, Kleinstiver BP, et al. Prediction of off-target activities for the end-to-end design of CRISPR guide RNAs. Nat Biomed Eng. 2018;2:38–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Shalem O, Sanjana NE, Hartenian E, et al. Genome-scale CRISPR-Cas9 knockout screening in human cells. Science. 2014;343:84–87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yuen G, Khan FJ, Gao S, et al. CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene knockout is insensitive to target copy number but is dependent on guide RNA potency and Cas9/sgRNA threshold expression level. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:12039–12053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zuris JA, Thompson DB, Shu Y, et al. Cationic lipid-mediated delivery of proteins enables efficient protein-based genome editing in vitro and in vivo. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:73–80 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tycko J, Myer VE, Hsu PD. Methods for optimizing CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing specificity. Mol Cell. 2016;63:355–370 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kim D, Bae S, Park J, et al. Digenome-seq: Genome-wide profiling of CRISPR-Cas9 off-target effects in human cells. Nat Methods. 2015;12:237–243 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Frock RL, Hu J, Meyers RM, et al. Genome-wide detection of DNA double-stranded breaks induced by engineered nucleases. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:179–186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yan WX, Mirzazadeh R, Garnerone S, et al. BLISS is a versatile and quantitative method for genome-wide profiling of DNA double-strand breaks. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1505–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Park J, Childs L, Kim D, et al. Digenome-seq web tool for profiling CRISPR specificity. Nat Methods. 2017;14:548–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cameron P, Fuller CK, Donohoue PD, et al. Mapping the genomic landscape of CRISPR-Cas9 cleavage. Nat Methods. 2017;14:600–606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Wang X, Wang Y, Wu X, et al. Unbiased detection of off-target cleavage by CRISPR-Cas9 and TALENs using integrase-defective lentiviral vectors. Nat Biotechnol. 2015;33:175–178 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Canver MC, Bauer DE, Dass A, et al. Characterization of genomic deletion efficiency mediated by Clusted Regularly Interspaced Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR)/Cas9 nuclease system in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem. 2014;289:21312–21324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Lin Y, Cradick TJ, Brown MT, et al. CRISPR/Cas9 systems have off-target activity with insertions or deletions between target DNA and guide RNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:7473–7485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kleinstiver BP, Tsai SQ, Prew MS, et al. Genome-wide specificities of CRISPR-Cas Cpf1 nucleases in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:869–874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kim D, Kim J, Hur JK, et al. Genome-wide analysis reveals specificities of Cpf1 endonucleases in human cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:863–868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pattanayak V, Lin S, Guilinger JP, et al. High-throughput profiling of off-target DNA cleavage reveals RNA-programmed Cas9 nuclease specificity. Nat Biotechnol. 2013;31:839–843 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Wu X, Scott DA, Kriz AJ, et al. Genome-wide binding of the CRISPR endonuclease Cas9 in mammalian cells. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:670–676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Kuscu C, Arslan S, Singh R, et al. Genome-wide analysis reveals characteristics of off-target sites bound by the Cas9 endonuclease. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32:677–683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Boyle EA, Andreasson JO, Chircus LM, et al. High-throughput biochemical profiling reveals sequence determinants of dCas9 off-target binding and unbinding. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:5461–5466 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Zhang L, Rube HT, Bussemaker HJ, et al. The effect of sequence mismatches on binding affinity and endonuclease activity are decoupled throughout the Cas9 binding site. BioRxiv. 2017;1–23 [Google Scholar]

- 85.Horlbeck MA, Witkowsky LB, Guglielmi B, et al. Nucleosomes impede Cas9 access to DNA in vivo and in vitro. Elife. 2016;5:e1267–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brinkman EK, Chen T, Amendola M, et al. Easy quantitative assessment of genome editing by sequence trace decomposition. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e16–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Yang Z, Steentoft C, Hauge C, et al. Fast and sensitive detection of indels induced by precise gene targeting. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:e5–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Güell M, Yang L, Church GM. Genome editing assessment using CRISPR Genome Analyzer (CRISPR-GA). Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2968–2970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Park J, Lim K, Kim J-S, et al. Cas-analyzer: An online tool for assessing genome editing results using NGS data. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:286–288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Xue LJ, Tsai CJ. AGEseq: Analysis of genome editing by sequencing. Mol Plant. 2015;8:1428–1430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Lindsay H, Burger A, Biyong B, et al. CrispRVariants charts the mutation spectrum of genome engineering experiments. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:701–702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Boel A, Steyaert W, De Rocker N, et al. BATCH-GE: Batch analysis of Next-Generation Sequencing data for genome editing assessment. Sci Rep. 2016;6:3033–0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Schaefer KA, Wu W-H, Colgan DF, et al. Unexpected mutations after CRISPR-Cas9 editing in vivo. Nat Methods. 2017;14:547–548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lareau CA, Clement K, Hsu JY, et al. Response to “Unexpected mutations after CRISPR-Cas9 editing in vivo”. Nat Methods. 2018;15:238-239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Lescarbeau RM, Murray B, Barnes TM, et al. Response to “Unexpected mutations after CRISPR-Cas9 editing in vivo.” Nat Methods. 2018;15:237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Wilson CJ, Fennell T, Bothmer A, et al. Response to “Unexpected mutations after CRISPR-Cas9 editing in vivo.“ Nat Methods. 2018;15:236–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kim S-T, Park J, Kim D, et al. Response to “Unexpected mutations after CRISPR-Cas9 editing in vivo.” Nat Methods. 2018;15:239–240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Nutter LMJ, Heaney JD, Lloyd KCK, et al. Response to “Unexpected mutations after CRISPR-Cas9 editing in vivo.” Nat Methods. 2018;15:235–236 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nature Methods. CRISPR off-targets: a reassessment. Nat Methods. 2018;15:229–230 [Google Scholar]

- 100.Iyer V, Boroviak K, Thomas M, et al. No unexpected CRISPR-Cas9 off-target activity revealed by trio sequencing of gene-edited mice. bioRxiv. 2018. [Epub ahead of print]; DOI: 10.1101/263129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Traxler EA, Yao Y, Wang Y-D, et al. A genome-editing strategy to treat β-hemoglobinopathies that recapitulates a mutation associated with a benign genetic condition. Nat Med. 2016;22:987–990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.McVey M, Lee SE. MMEJ repair of double-strand breaks (director's cut): Deleted sequences and alternative endings. Trends Genet. 2008;24:529–538 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Maeder ML, Gersbach CA. Genome-editing technologies for gene and cell therapy. Mol Ther. 2016;24:430–446 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Doudna JA. Genomic engineering and the future of medicine. JAMA. 2015;313:791–792 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cyranoski D. CRISPR gene-editing tested in a person for the first time. Nature. 2016;539:47–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sheridan C. CRISPR therapeutics push into human testing. Nat Biotechnol. 2017;35:3–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Bauer DE, Kamran SC, Lessard S, et al. An erythroid enhancer of BCL11A subject to genetic variation determines fetal hemoglobin level. Science. 2013;342:253–257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Canver MC, Smith EC, Sher F, et al. BCL11A enhancer dissection by Cas9-mediated in situ saturating mutagenesis. Nature. 2015;527:192–197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Acuna-Hidalgo R, Veltman JA, Hoischen A. New insights into the generation and role of de novo mutations in health and disease. Genome Biol. 2016;17:24–1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Gasch AP, Payseur BA, Pool JE. The power of natural variation for model organism biology. Trends Genet. 2016;32:147–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Yalcin B, Wong K, Agam A, et al. Sequence-based characterization of structural variation in the mouse genome. Nature. 2011;477:326–329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Keane TM, Goodstadt L, Danecek P, et al. Mouse genomic variation and its effect on phenotypes and gene regulation. Nature. 2011;477:289–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Berger J, Suzuki T, Senti KA, et al. Genetic mapping with SNP markers in Drosophila. Nat Genet. 2001;29:475–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Chen D, Ahlford A, Schnorrer F, et al. High-resolution, high-throughput SNP mapping in Drosophila melanogaster. Nat Methods. 2008;5:323–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Cao J, Schneeberger K, Ossowski S, et al. Whole-genome sequencing of multiple Arabidopsis thaliana populations. Nat Genet. 2011;43:956–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Blake JA, Eppig JT, Kadin JA, et al. Mouse Genome Database (MGD)-2017: Community knowledge resource for the laboratory mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D723–D729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Chen D, Berger J, Fellner M, et al. FLYSNPdb: A high-density SNP database of Drosophila melanogaster. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:567–570 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Zhou B, Ho S, Zhu X, et al. Comprehensive, integrated and phased whole-genome analysis of the primary ENCODE cell line K562. BioRxiv. 2018;1–49 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Nelson MR, Wegmann D, Ehm MG, et al. An abundance of rare functional variants in 202 drug target genes sequenced in 14,002 people. Science. 2012;337:100–104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Scharfe CPI, Tremmel R, Schwab M, et al. Genetic variation in human drug-related genes. Genome Med. 2017;9:11–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Pinto N, Dolan ME. Clinically relevant genetic variations in drug metabolizing enzymes. Curr Drug Metab. 2011;12:487–497 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]