Abstract

Objective

To analyse the most frequent self-reported adverse reactions (ARs), the durability and the causes of antiretrovirals (ARVs) regimens change, concomitant treatments and drug interactions related to the use of ARVs in a group of people living with HIV in Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico.

Materials and methods

Cross-sectional study conducted in a clinic specialising in HIV ‘CAPASITS-Cuernavaca’ in Mexico from February to June 2015. People who wanted to participate were given a questionnaire on demographic characteristics, adherence, concomitant treatments and ARs. To understand the clinical variables, the clinical records were reviewed. Quantitative variables were compared using Student’s t-test for normal data and the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normal data. For comparisons between categorical variables, the χ2 test was used. All tests used a significance level of 0.05.

Results

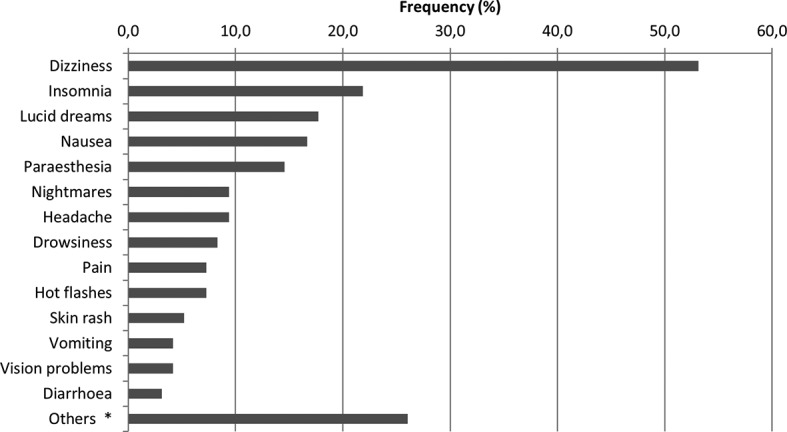

A total of 96 people participated, and 218 ARs (mean= 2.3±1.9) were found. The most frequently encountered ARs were dizziness (53.1%), insomnia (21.9%) and lucid dreams (17.7%). Twenty-three people (24%) were polymedicated, and 18 potential interactions were detected in 12 people.

Conclusions

The results suggest that a thorough analysis of the possible drug interactions should be performed for polymedicated people on ARV treatment and that a protocol should be designed for the monitoring and management of AR to ensure a good adherence to ARV treatment.

Keywords: antiretroviral, adverse reactions, HIV, polymedication, drug interactions

Introduction

More than 20 antiretrovirals (ARVs) have been adopted for the treatment of HIV infection type 1 (HIV-1).1 Currently, in Mexico, only some of these ARVs are recommended in combination for both initial and rescue therapy (CENSIDA, 2014).1 The main objective of ARV treatment is to reduce the viral plasma load for as long as possible, producing a positive impact on restoring the immune system, with a gradual increase in the CD4 lymphocyte counts. This increase is reflected in a decrease in morbi-mortality and an increase in the health-related quality of life.2 However, these benefits require the timely prescription of ARV drugs, the monitoring of their sustained viral suppressor effect and the prevention of and timely actions taken against the emergence of drug-related problems.

The use of ARVs is associated with adverse effects of varying nature and severity and should be considered when selecting the therapeutic scheme.3 A large amount of complications that can endanger the patient’s life (liver toxicity) favour the abandonment or contribute to non-adherence to ARV treatment (such as psychiatric symptoms: anxiety and depression) or increase the risk of cardiovascular disease (dyslipidaemia, insulin resistance).4–6 A very important aspect during ARV therapy is to identify, prevent and manage adverse reactions (ARs) to achieve the therapeutic objective.

It has been previously demonstrated in a wide variety of chronic diseases that providers consistently under-report patients’ symptoms and ARs severity.7–8 It has been observed that the clinical importance of ARs reported by patients is more strongly associated with health-related quality of life, survival or risk of hospitalisation than the ARs reported by providers.9 An accurate assessment of the symptoms reported by the patients can be a good option, relatively inexpensive and clinically relevant, that can help optimise adherence to ARV treatments.10

We must also take into account that in people living with HIV, the use of concomitant treatments is common and increases with the presence of co-morbidities and/or increasing age.11 According to the definition of the WHO, polypharmacy is ‘the administration of multiple drugs simultaneously’,12 which leads to an increase in likely drug interactions, duplication of treatment and increased adverse effects; polypharmacy is another barrier to therapeutic compliance, as it is associated with increased risk of non-adherence.13 It is estimated that the clinically relevant interactions between ARVs and concomitant medications can reach rates of 20% to 40% and could have fatal consequences.14–15 In Mexico, several clinics specialise in HIV care; however, there are few records of the ARs and drug interactions presented most frequently when using ARVs. The objective of this work was to analyse the most frequent patient-reported ARs, concomitant treatments and drug interactions related to the use of efavirenz (EFV) in a clinic specialising in HIV. The durability and the causes of ARVs treatment change related to ARs have also been described.

Materials and methods

The study was conducted in ‘CAPASITS-Cuernavaca’, a clinic specialised in HIV, from February to June 2015. The city of Cuernavaca is located in the State of Morelos, 77 km away from Mexico City. In Mexico, public health services have provided universal access to ARV therapy since the year 2000. ‘CAPASITS-Cuernavaca’ launched this service on July 2003 and on January 2016 a total of 1426 people living with HIV were receiving medical care. Nine hundred of them are being benefited with ARV treatment. ‘CAPASITS-Cuernavaca’ is a health unit that provides services for the prevention and specialised care of patients with HIV and sexually transmitted infections, on an outpatient basis. It has medical, dental, psychological, nutritional and social work services. The pharmaceutical care service, where ARs are recorded, was established on January 2016.

The management of ARs is performed according to their severity. If the AR does not put at risk the life of the patient, pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies are employed to manage symptoms, maintaining the same ARV therapy. If the AR continues and it is considered severe, the ARV must be replaced.

The current study is a secondary analysis of a prior work called ‘CYP2b6 Gene Polymorphisms and Efavirenz Plasma Concentrations’ (unpublished data). Recruitment criteria included people at least 18 years of age living with HIV, with ARV treatment that included EFV and routine medical consultation at a ‘CAPASITS-Cuernavaca’. Pregnant women, imprisoned people or people with psychiatric disorders were excluded from the study. The following parameters from the prior study were used to calculate the sample size: total population of patients on EFV therapy 700, allelic frequencies of the CYP2b6 previously reported by Haas et al 16 for a Hispanic population 35% and 95% CI with a marginal error of 10%.

The project was approved by the Bioethics Committee of the Henry Dunant Hospital in Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico (20 February 2015). All participants, after signing informed consent, were administered a questionnaire on demographic characteristics, adherence, concomitant treatments and AR, by a trained clinical pharmacist. The questionnaire included a list of common EFV-related symptoms which were identified based on clinical experience and previous reports.17

The clinical records were reviewed to discover ARV and concomitant treatments, HIV viral load, CD4 lymphocyte count and reasons for ARV treatment changes. ARs were taken as any undesirable symptoms reported by the participants that were perceived to be the result of the use of EFV. In order to convert the ARs into dichotomous variable, the patient-reported ARs were stratified into two groups: low (0–2 symptoms) and high (≥3 symptoms). Mean number of patient-reported ARs was considered as the cut-off point. A person was considered polymedicated when taking three or more drugs, not including the ARV. Treatment adherence was evaluated through the implementation of the Simplified Scale for Detecting ARV Adherence Problems (SSDAAP) questionnaire as described by Ventura-Cerdá et al,18 which consists of six questions with dichotomous responses: positive or negative. The scale is scored one point for each positive response and zero point for each negative response. The total score is the sum of the responses (1 point minimum and 6 points maximum). The first two questions must be answered positively to consider the patient free of adherence problems. If any of the two is negative, the total score is one point, regardless the rest of the answers. The patients were considered adherent (5–6 points) or non-adherent (1–4 points). For the detection of drug interactions, the database of HIV drug interactions maintained at the University of Liverpool (www.hiv-druginteractions.org)19 was consulted, which classifies interactions as drugs that cannot be co-administered, drugs with potential interactions (PIs) and drugs that are not expected to interact (the latter were not considered in the analysis). Only ARV–non-ARV drug interactions were considered.

Descriptive analyses of participants were carried out. Continuous variables were expressed in mean and SD. The association of continuous variables were made by Student’s t-test for normal data, or the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normal data. Comparisons between categorical variables used the χ2 test. All tests had a significance level of 0.05. The Statistical Package for Social Sciences window version 20 (IBM Statistics, USA) software was used for the statistical analysis.

Results

There were 105 patients invited and 101 accepted to participate. Five patients were excluded because there was not enough information in clinical records or they could not answer the entire questionnaire. A total of 96 participants were included; the demographic and clinical characteristics of the population are listed in table 1. In total, 83.3% of the participants were male, the average age was 37 years±11.1 and the average time of HIV diagnosis was 63.1±46.6 months. Most of the population had more than 9 years of schooling (55.2%), and 10.4% of the population reported abusing drugs.

Table 1.

General features of the population

| n (%) | |

|

Sex

Men Women |

80 (83.3) 16 (16.7) |

|

Schooling

Less than 9 years More than 9 years No response |

37 (38.5) 53 (55.2) 6 (6.3) |

|

Drug use

Yes No |

10 (10.4) 86 (89.6) |

|

Viral load (copies RNA/mL)

<40 >40 |

80 (83.3) 16 (16.7) |

|

CD4 cells (cells/mm3)

<200 200–350 >350 |

11 (11.5) 15 (15.6) 70 (72.9) |

|

Current treatment

Emtricitabine/tenofovir/efavirenz Lamivudine/abacavir/efavirenz |

82 (85.4) 14 (14.6) |

|

Initial treatment

Emtricitabine/tenofovir/efavirenz Lamivudine/abacavir/efavirenz Lamivudine/zidovudine/efavirenz Other |

50 (52.1) 16 (16.7) 16 (16.7) 14 (14.6) |

|

Adherence

Yes No |

75 (78.1) 21 (21.9) |

|

ARVs regimens

First line Second line Third line Fourth line |

62 (64.6) 26 (27.1) 6 (6.3) 2 (2.1) |

ARV, antiretrovirals.

At the time of the study, all participants took EFV, either in combination with emtricitabine (FTC) and tenofovir (TDF) (85.5%) or in combination with lamivudine/abacavir. Sixty-two participants (64.6%) were in their first-line ARV regimen, and 34 people had passed to a second-line regimen. The main reason for this change was the presence of ARs, followed by simplification of treatment; one patient exhibited virological failure. Of these 34 people, 26 (76.4%) remained in the second-line regimen. Six (17.6%) had passed to a third-line regimen, and two (5.8%) were in their fourth-line ARV regimen (table 1). Other reported reasons for changes in ARV treatment included personal reasons, shortages of medicine, information not recorded in the chart or inability to refrigerate the drug (ritonavir) (table 2).

Table 2.

Duration and reasons for changing treatment regimen

| ARV regimen | |||

| First to second n=34 |

Second to third n=8 |

Third to fourth n=2 |

|

| Duration of ARVs regimen (years) mean±SD |

3.9±2.8 | 3.6±3.5 | 7.4±0.2 |

| Adverse reactions, n (%) Lipodystrophies (n) Peripheral neuropathy Myalgias/arthralgias Hypertriglycerida emia Ana emia Hypersensitivity rash Jaundice Dysphagia |

13 (38.2) 6 2 1 1 1 1 1 |

2 (25) 1 1 |

1 (50) 1 |

| Simplification (n) | 11 (32.3) | 5 (62.5) | 1 (50) |

| Virological failure (n) | 1 (2.9) | ||

| Other (n) | 9 (26.4) | 1 (12.5) | |

ARV, antiretroviral.

Patient-reported ARs

A total of 218 ARs declared by the participants were identified, which is equivalent to 2.3 (±1.9) reactions per person on average; 84 patients (87.5%, 95% CI 79.3% to 92.9%) reported at least one AR. The ARs identified most frequently included dizziness (53.1%, 95% CI 43.2% to 62.8%), insomnia (21.9%, 95% CI 14.7% to 31.2%), lucid dreams (17.7%, 95% CI 11.3% to 26.6%) and nausea (16.7%, 95% CI 10.4% to 25.5%) (figure 1). In four cases, drugs were required to treat the AR, and a single case required hospitalisation. The group of non-adherent participants suffered more ARs on average than the adherent group (3.2 vs 1.9, respectively, p=0.006) (table 3). Although no statistically significant differences were detected for the other variables analysed, it was noted that the people who reported high ARs took more medication on average (polymedication 1.9 vs 1.5, p=0.262), had more months of ARV treatment (46.5 months vs 38.6, p=0.301) and had longer time intervals since their diagnosis of infection (62.7 months vs 60.4 months, p=0.597) than people with low ARs. There were no differences with the sociodemographic variables: sex, drugs use and schooling (data not shown).

Figure 1.

Main self-reported adverse reactions. *Others: fatigue, lipothymy, gastritis, hallucinations and acidity.

Table 3.

Analysis of adverse reactions, adherence, potential interactions and polymedication

| Adverse reactions | Adherence | Potential interactions | Polymedication | |||||||||

| n= | High 38 |

Low 58 |

p | Yes 75 |

No 21 |

p | Yes 12 |

No 84 |

p | Yes 23 |

No 73 |

p |

| Adverse reactions | – | – | – | 1.96 | 3.28 | 0.006 | 2.75 | 2.2 | 0.352 | 2.7 | 2.1 | 0.177 |

| Potential interactions | – | – | – | – | – | – | ||||||

| Yes | 6 | 6 | 0.532* | 10 | 2 | 1.000* | ||||||

| No | 32 | 52 | 65 | 19 | ||||||||

| Polymedication | 1.9 | 1.5 | 0.262 | 1.5 | 2.1 | 0.139 | 2.91 | 1.44 | 0.001 | – | – | – |

| Age (years) mean | 35.0 | 38.04 | 0.299 | 37.7 | 34.9 | 0.329 | 42.5 | 36.3 | 0.073 | 41.9 | 35.6 | 0.012 |

| Viral load (log10 copies RNA/mL) | 1.6 | 2.03 | 0.572 | 1.8 | 1.7 | 0.748 | 2.25 | 1.75 | 0.013 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 0.255 |

| CD4 count (cells/mm3) | 503 | 504 | 0.527 | 490 | 557 | 0.202 | 329 | 529 | 0.01 | 496 | 507 | 0.850 |

| Time of EFV treatment (months) | 46.5 | 38.6 | 0.301 | 43.1 | 36.8 | 0.667 | 23.9 | 44.3 | 0.108 | 50.3 | 39 | 0.241 |

| Time since HIV diagnosis (months) | 67.2 | 60.4 | 0.597 | 64 | 60 | 0.753 | 41.9 | 66.1 | 0.068 | 79.1 | 58 | 0.075 |

*χ2 test. Polymedication was defined as patients taking three or more drugs, not including the antiretroviral. Adverse reactions: low (0–2 symptoms) and high (≥3 symptoms).

Drug interactions

A total of 18 drug interactions were found, all of which were PIs. There were no interactions of drugs that could not be co-administered. Twelve people (12.5%) had one or more PIs. The PI that presented most frequently was itraconazole/TDF/EFV (six people), followed by pravastatin/EFV (three people) and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole/FTC (three people). Naproxen/FTC/EFV/TDF and diclofenac/EFV/TDF both presented in two people, and warfarin/EFV and verapamil/TDF/EFV each presented in one person. Naproxen was self-medicated in one of the two cases found.

The average age of the participants with one or more PI was greater than the age of those who did not have any PIs (42.5 years vs 36.3 years, p=0.073) (table 3).

Analysis of the relationship between the presence of PI and viral load revealed that 41.7% of the people who reported a PI presented an average viral load of 2.25 log10 copies RNA/mL, while those without PIs had a viral load of 1.75 log10 copies RNA/mL (p=0.013). There were also differences in CD4 counts: the group of people without PIs had higher CD4 counts than the group with PIs (529 vs 329 cells/mm3, respectively, p=0.01) (table 3).

Polymedication

It was found that 23 people (24%) were polymedicated. The average age of polymedicated people was 41.9 years±10.7, while those who were not polymedicated had an average age of 35.6 years±10.9, p=0.012. Likewise, it was noted that the polymedicated people had more PIs than the non-polymedicated (p=0.001).

Discussion

This work found that participants take 3.9 years on average to reach the first change in their ARV regimen (table 2). These data differ from those presented in a study from Spain in which the average duration for the change of the first-line ARV regimen was <1.5 years.2 Another study conducted in the USA reported averages of 1.7 years in the first-line regimen, 1.2 years in the second-line regimen and 1.5 years in the third-line regimen.20 More recently, a Spanish population showed better tolerance to ARV treatments in regimens containing non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors, with an average of 31 months reported.21 The reasons for shorter times between changes in the ARV regimen in these countries could be related to the fact that these locations have more alternatives for ARV treatment and better recording of ARs that allow the doctor to modify or change the ARV regimen.

According to the information reported by participants, 87.5% suffered at least one AR, results that match those reported in other studies.22–23 Likewise, differences were observed in the number of patient-reported ARs between adherent and non-adherent participants. Ickovics et al 24 reported that patients without ARs were 12.8 times more likely to present 95% or greater adherence when compared with patients with ARs. In the Adherence Italian Cohort Naive Antiretrovirals (AdICONA) study, non-adherent patients reported an average of ARs higher than adherent patients.10 These results lead us to assume that perception of the patients´ health could be contributing to the low adherence to ARVs, that is, when a patient begins feeling that the use of their therapy causes discomfort, they stop taking it or take it inappropriately.

This work reports that the change in ARVs regimens took place mainly as the result of severe ARs. Mild or moderate ARs like the ones reported by the patients in this study can be managed by pharmacological and non-pharmacological strategies only for the management of symptoms. Nevertheless, the physician or the pharmacist must be alert to detect those persons who report ARs, even though these ARs are mild or moderate providing information about the most frequent ARs and establishing the appropriate intervention strategies to prevent and manage them. These strategies should diminish the non-adherence risk and therefore should also diminish the risk of ARVs treatment failure.

It was noted that the group of polymedicated people had greater numbers of ARs and PIs and greater age, which is understandable, as older age increases co-morbidities, such as cardiovascular disease, osteoporosis, dislipidaemias and diabetes mellitus.11 This relationship gives rise to individuals who suffer from consuming a greater number of drugs not related to the ARV therapy, putting them at risk of suffering more AR and drug interactions, many of which can be PIs that require dose adjustment or close monitoring and even drug interactions that can put their lives at risk.

Likewise, it was noted that in the group of non-adherent participants, a greater number of drugs were administered. Even if the data were not statistically significant, they agree with those reported by Cantudo-Cuenca et al,13 who noted that polymedication is a predictor of non-adherence to ARV treatment. It is important to remember that adherence is a determining factor in the effectiveness of suppressing viral replication, avoiding resistance and minimising co-morbidities.25

The total percentage of clinically relevant interactions found in this population was 18.7%, a lower rate than reported recently by Cervero et al 26 in Spain, who found that 29.11% of a group of 142 participants had at least one PI. These differences can be mainly due to differences in the prescribed ARV regimes between these two populations.

This study observed that the group of participants with PIs had a higher viral load and a lower number of CD4 cells than the group without PIs. These data may suggest that the effectiveness of ARV treatment could be compromised by PIs. Previous studies using other ARVs found no association between viral load and the presence of PIs.15–27 Therefore, it is very important to carry out more studies to determine the clinical relevance of PIs, in particular those in which coadministration has not been studied.

Furthermore, in Mexico, there is a strong tendency for self-medication, to the extent that some reports have considered this behaviour a health problem.28–29 Therefore, it is important to consider the risk of administering ARVs as pre-exposure prophylaxis, as is practised in some countries as a way to reduce the incidence of HIV infection.30 In addition, we must consider the use of recreational drugs and medicinal plants that could interact with ARVs to make them less effective and that could also generate ARs that could put lives at risk.

Finally, even if the main therapeutic objective of the ARV therapy is achieved in this group of people, that is, to diminish the viral load and to establish high CD4 levels, it is also necessary to achieve effective and safe ARV regimes that are capable of reducing ARs to promote adherence to treatment and to improve the quality of life.

Based on the results obtained in this study, we can assume that polymedication could generate an increase in PIs. These types of interactions can modify the pharmacokinetics or pharmacodynamics of ARVs and could lead to an increase in viral load and a decrease of CD4 lymphocytes. Furthermore, polymedication may cause an increase in ARs as a result of non-adherence to ARVs. Supported on these results and in the clinical practice carried out in ‘CAPASITS-Cuernavaca’ health unit as well as the recommendations described in the ‘ARV Management Guide for people with HIV / AIDS’,1 it is suggested to incorporate professional pharmaceutical practices such that during polymedication, the following can be achieved: (a) drug interactions should be analysed to identify those that are contraindicated or potentially contraindicated; (b) validated protocols should be produced to determine the adherence to ARV treatments; and (c) doctors and pharmacists should have access to the list of drugs that the patient is receiving, with information on doses and times of treatment, even if they belong to other areas, so that ARV prescriptions can be given safely and effectively.

Key messages.

What is already known on this subject

Several studies have independently analysed the importance of clinical significance of adverse reactions (ARs), polymedication and drug interactions, good adherence efficacy to ensure antiretroviral (ARV) success and duration of ARV treatment regimens in the course of HIV infection.

What this study adds

This work analysed the most frequent patient-reported ARs, durability and the causes of ARV regimens change, concomitant treatments and drug interactions related to the use of ARVs in a clinic specialising in HIV. Our results indicate that polymedication is associated with potential interactions and greater numbers of ARs, which in turn could generate low adherence to ARV treatment and an increase in the viral load. All these factors could favour the therapeutic failure. Even when the therapeutic failure is a multifactorial process, understanding the role of each of these factors is important to improve quality of life.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Lic. Norma Beatriz García Fuentes, Morelos coordinator of the HIV/AIDS and STIs Program, the laboratory technologist Adriana Pérez for her support during data collection and the HIV population for their voluntarily participation in the study.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by CONACYT through a postdoctoral fellowship for María Fernanda Martínez-Salazar in "Programa de Doctorado en Investigación en Medicina" of the Escuela Superior de Medicina-Instituto Politécnico Nacional and SIP project (SIP-20161162 to MDC)

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Correction notice: This paper has been amended since it was published Online First. Owing to a scripting error, some of the publisher names in the references were replaced with ’BMJ Publishing Group'. This only affected the full text version, not the PDF. We have since corrected these errors and the correct publishers have been inserted into the references.

References

- 1. Guía de manejo antirretroviral de las personas con VIH. México: Censida/Secretaría de Salud, 2014. www.censida.salud.gob.mx/descargas/principal/Guia_ARV_2014V8.pdf (accesed sep 10 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gratacòs L, Tuset M, Codina C, et al. Tratamiento antirretroviral de la infección por el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana: duración y motivos de cambio del primer esquema terapéutico en 518 pacientes. Med Clin 2006;126:241–5. 10.1157/13085280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Subbaraman R, Chaguturu SK, Mayer KH, et al. Adverse effects of highly active antiretroviral therapy in developing countries. Clin Infect Dis 2007;45:1093–101. 10.1086/521150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jena A, Sachdeva RK, Sharma A, et al. Adverse drug reactions to nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase Inhibitor-Based antiretroviral Regimen: A 24-Week prospective study. J Int Assoc Physicians AIDS Care (Chic) 2009;8:318–22. 10.1177/1545109709343967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bucher HC, Rickenbach M, Young J, et al. ; Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Randomized trial of a computerized coronary heart disease risk assessment tool in HIV-infected patients receiving combination antiretroviral therapy. Antivir Ther 2010;15:31–40. 10.3851/IMP1475 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Leutscher PD, Stecher C, Storgaard M, et al. Discontinuation of efavirenz therapy in HIV patients due to neuropsychiatric adverse effects. Scand J Infect Dis 2013;45:645–51. 10.3109/00365548.2013.773067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Ottervanger JP, Valkenburg HA, Grobbee DE, et al. Differences in perceived and presented adverse drug reactions in general practice. J Clin Epidemiol 1998;51:795–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Wyshak G, Barsky AJ. Relationship between patient self-ratings and physician ratings of general health, depression, and anxiety. Arch Fam Med 1994;3:419–24. 10.1001/archfami.3.5.419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Justice AC, Chang CH, Rabeneck L, et al. Clinical importance of provider-reported HIV symptoms compared with patient-report. Med Care 2001;39:397–408. 10.1097/00005650-200104000-00010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ammassari A, Murri R, Pezzotti P, et al. ; AdICONA Study Group. Self-reported symptoms and medication side effects influence adherence to highly active antiretroviral therapy in persons with HIV infection. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2001;28:445–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Edelman EJ, Gordon KS, Glover J, et al. McNicholl IR, Fiellin DA, Justice AC. The next therapeutic challenge in HIV: Polypharmacy. Drugs & Aging 2013;30:613–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. World_Health_Organization. A glossary of terms for community health care and services for older persons. Ageing Heal Tech Rep 2004;5:11 www.who.int/kobe_centre/ageing/ahp_vol5_glossary.pdf (accesed 10 Sep 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 13. Cantudo-Cuenca MR, Jiménez-Galán R, Almeida-González CV, et al. Concurrent use of comedications reduces adherence to antiretroviral therapy among HIV-Infected patients. J Manag Care Pharm 2014;20:844–50. 10.18553/jmcp.2014.20.8.844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. De Maat MM, De Boer A, Koks CH, et al. Evaluation of clinical pharmacist interventions on drug interactions in outpatient pharmaceutical HIV-care. J Clin Pharm Ther 2004;29:121–30. 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2003.00541.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Marzolini C, Elzi L, Gibbons S, et al. ; Swiss HIV Cohort Study. Prevalence of comedications and effect of potential drug-drug interactions in the swiss HIV Cohort Study. Antivir Ther 2010;15:413–23. 10.3851/IMP1540 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Haas DW, Smeaton LM, Shafer RW, et al. Pharmacogenetics of long-term responses to antiretroviral regimens containing Efavirenz and/or Nelfinavir: an Adult Aids Clinical Trials Group Study. J Infect Dis 2005;192:1931–42. 10.1086/497610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Margolis AM, Heverling H, Pham PA, et al. A review of the toxicity of HIV medications. J Med Toxicol 2014;10:26–39. 10.1007/s13181-013-0325-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ventura-Cerdá JM, Mínguez-Gallego C, Fernández-Villalba EM, et al. Escala simplificada para detectar problemas de adherencia (ESPA) al tratamiento antirretroviral. Farm Hosp 2006;30:171–6. 10.1016/S1130-6343(06)73968-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. HIV drug interaction. www.hiv-druginteractions.org (accesed nov 10 2016).

- 20. Gardner EM, Burman WJ, Maravi ME, et al. Durability of adherence to antiretroviral therapy on initial and subsequent regimens. AIDS Patient Care STDS 2006;20:628–36. 10.1089/apc.2006.20.628 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. De La Torre-Lima J, Aguilar A, Santos J, et al. ; Málaga Infectious Disease Group. Durability of the first antiretroviral treatment regimen and reasons for change in patients with HIV infection. HIV Clin Trials 2014;15:27–35. 10.1310/hct1501-27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tadesse WT, Mekonnen AB, Tesfaye WH, et al. Self-reported adverse drug reactions and their influence on highly active antiretroviral therapy in HIV infected patients: a cross sectional study. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol 2014;15:1–9. 10.1186/2050-6511-15-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Menezes de Pádua CA, César CC, Bonolo PF, et al. Self-reported adverse reactions among patients initiating antiretroviral therapy in Brazil. Brazilian J Infect Dis 2007;11:202–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Ickovics JR, Cameron A, Zackin R, et al. ; Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group 370 Protocol Team. Consequences and determinants of adherence to antiretroviral medication: results from adult AIDS clinical trials group protocol 370. Antivir Ther 2002;7:185–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lima VD, Harrigan R, Bangsberg DR, et al. The combined effect of modern highly active antiretroviral therapy regimens and adherence on mortality over time. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2009;50:529–36. 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31819675e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Cervero M, Torres R, Jusdado JJ, et al. Factores predictivos de las interacciones farmacológicas clínicamente significativas en los pacientes tratados con regímenes basados en inhibidores de proteasa, inhibidores de transcriptasa inversa no nucleósidos y raltegravir. Med Clin 2016;146:339–45. 10.1016/j.medcli.2016.01.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Iniesta-Navalón C, Franco-Miguel JJ, Gascón-Cánovas JJ, et al. Effect of drug interactions involving antiretroviral drugs on viral load in HIV population: Table 1. Eur J Hosp Pharm 2016;23:241–3. 10.1136/ejhpharm-2015-000670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sánchez-Bermúdez C, Nava Galán MG. Análisis de la automedicación como problema de salud. Enf Neurol 2012;11:159–62. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Angeles-Chimal P, Medina-Flores M, Molina-Rodríguez JF. Automedicación en una población urbana de cuernavaca, Morelos. Salud Publica Mex 1992;34:554–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baeten JM, Haberer JE, Liu AY, et al. Pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: Where have we been and where are we going? J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2014;63:S122–S129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]