Abstract

Neural stem cells (NSCs) can proliferate and differentiate into multiple cell types that constitute the nervous system. NSCs can be derived from developing fetuses, embryonic stem cells, or induced pluripotent stem cells. NSCs provide a good platform to screen drugs for neurodegenerative diseases and also have potential applications in regenerative medicine. Natural products have long been used as compounds to develop new drugs. In this review, natural products that control NSC fate and induce their differentiation into neurons or glia are discussed. These phytochemicals enable promising advances to be made in the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases.

Keywords: Neural stem cells, Cell fate, Neurogenesis, Differentiation, Antioxidative, Neuroprotection

INTRODUCTION

Stem cells (SCs) can self-renew and differentiate into various cell types (Kim, 2011). Embryonic stem cells (ESCs) are derived from the inner cell mass of the blastocyst and because they can be differentiated into all types of cells that the body is composed of, they are referred to as pluripotent (Thomson et al., 1998). Neural stem cells (NSCs) or neural progenitor cells (NPCs) can proliferate but can only differentiate into neural cells such as neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes, and are therefore categorized as multipotent (Gage, 2000). The identification of SCs has led to promising advances in the treatment of diseases since these cells have the potential to replace damaged cells after differentiation into the appropriate cell types. However, more research is required to overcome immune rejection after transplantation and to be able to safely and successfully transplant ectopically managed cells into the body before ESCs or induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSCs) can be used for regenerative medicine. SCs, especially human SCs, provide an efficient platform for the development of new drugs because they can be used to evaluate the efficacy and toxicity of drug candidates (Kim and Jin, 2012). Controlling SC fate by chemicals and natural products has potential applications in therapeutic use. Natural products are chemical compounds or substances endogenously produced by living organisms such as plants and animals. Natural products have been important sources for developing medicinal treatments. Traditionally, plant extracts were used in Asian countries to treat injuries or diseases (referred as traditional medicine) and have recently attracted attention for their potential to be developed into novel drugs (Harvey et al., 2015). Not only can normal cells that are lost in patients suffering from diseases be regenerated, but limitations of cell-based regenerative medicine can also be overcome by facilitating the production of neurons or glia from endogenous NSCs in the brain. Thus, molecules that control endogenous SCs or NSCs can be used as pharmacological agents to treat neurodegenerative diseases. Phytochemicals have recently been recognized as alternatives for treating neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (Shal et al., 2018). They are known to have anti-oxidative and anti-inflammatory effects and to increase cell survival (Dar et al., 2016; Kornberg et al., 2018; Safaeinejad et al., 2018). Moreover, some natural products have been reported to control NSC fate (Liu et al., 2007; Dong et al., 2012; Kim and Jin, 2012; Kong et al., 2015). This review focuses on recent evidence that NSC fate can be regulated by natural products.

NSCS/NPCS FOR NEURODEGENERATIVE DISEASES

Neurodegenerative diseases including Parkinson’s disease (PD), AD, and Huntington’s disease (HD) are caused by neuronal loss and subsequent brain malfunction (MacDonald et al., 1993; Kim, 2011). For example, in PD, dopaminergic (DA) neurons, whose cell bodies are located in the substantia nigra and project into the striatum, are lost (Kim, 2011). Because DA neurons control movement, patients with PD suffer from bradykinesia, rigidity, and depression. AD is a neurodegenerative disease that results in the loss of memory, which leads to dementia due to the loss of neurons in the basal forebrain, hippocampus, and cortex (Monroy et al., 2013). HD is caused by a mutated HTT gene that has expanded CAG repeats, which encode poly-glutamine stretches resulting in a dopamine imbalance in the striatum (MacDonald et al., 1993). Patients with HD show abnormal dance-like movements and progressive breakdown of nerve cells in the brain (Chen et al., 2013). Mainly striatal and cortical neurons are lost in HD (Chen et al., 2013). Studies to recover or replace neurons have been extensively pursued and the discovery of SCs that can be manipulated to produce cells of interest has led to promising advances for novel therapies.

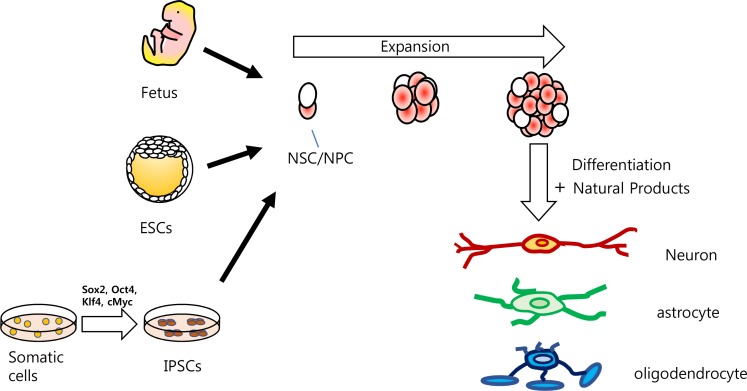

A study performed in 1965 reported that many granule cells of the dentate gyrus (DG) are newly generated as determined by thymidine-H3 injection in young rats (Altman and Das, 1965). In the human DG, neurogenesis was also confirmed to occur in adults (Eriksson et al., 1998; Goncalves et al., 2016). These findings provide evidence that in some areas of the adult brain, including the subventricular zone of the hippocampal DG, new neurons can be generated by controlling residing endogenous NSCs with suitable stimuli. The identification of cells or NSCs that can generate neurons in the adult brain initiated studies to discover drugs that can modulate NSC fate into specific neurons or glia (Kong et al., 2015; Shin et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2016). With advances in NSC culture from developing animals, human ESCs, or IPSCs, NSCs have been used to generate lost neurons to treat neurodegenerative diseases or study mechanisms of neuro-degeneration or neuro-regeneration (Fig. 1) (Reynolds et al., 1992; Reynolds and Weiss, 1992; Schneider et al., 2007; Akhtar et al., 2018). However, protocols that are currently used for the derivation of NSCs or neurons from ESCs or IPSCs still produce other types of cells and have the possibility of forming teratomas (Cieslar-Pobuda et al., 2017). Thus, the protocols need to be optimized before they can be applied in regenerative medicine. Recently, in addition to soluble factors that are required for proper cell development, culture dish surfaces and microfluidic chambers that are effective in generating gradients of soluble factors have also been studied to identify the optimal environment for SC culture and differentiation (Cha et al., 2017; Kim et al., 2018).

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of cells that can produce neurons and glia. Neural stem cells (NSCs) or neural progenitor cells (NPCs) can be derived from the fetus, embryonic stem cells (ESCs), and induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSCS). NSCs/NPCs proliferate in the presence of mitogens and can differentiate into neurons, astrocytes, or oligodendrocytes with the appropriate stimuli and/or in the presence of natural products.

NSCs derived from the fetus only generate neural cells and do not form teratomas. These cells are more committed than ESCs and are restricted to production of desired neurons. However, fetus-derived NSCs are still useful for studying the development of the nervous system and for drug screening and regenerative medicine (Kong et al., 2015; Shin et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2016; Kong et al., 2018). NSCs derived from developing fetuses demonstrate an in vivo developmental sequence in that they produce neurons first, then astrocytes, followed by oligodendrocytes. Although they are restricted, NSCs can be induced to generate neurons and glia by chemicals or growth factors (Sauvageot and Stiles, 2002). In addition, depending on the brain region from which they are derived, NSCs show specific characteristics (Kim et al., 2009). Animal brain sizes have increased throughout evolution, and different regions of the brain develop at specific rates (Bradbury, 2005; Paredes et al., 2016). For example, the cortex expands faster and to a greater extent than other areas of the brain and neurons generated from the midbrain are on average longer than those generated from the cortex. Interestingly, these characteristics are recapitulated in NSCs/NPCs derived from different regions such as the cortex and midbrain (Kim et al., 2009). Human NSCs/NPCs derived from the developing cortex are highly proliferative and produce large numbers of neurons, whereas NSCs from the midbrain divide slowly and produce fewer neurons (Kim et al., 2009). The specific regional characteristics are retained when ectopic genes are introduced. For example, transduction of ASCL1 can generate neurons from NSCs derived from the midbrain, and these ASCL1-generated neurons from the midbrain were bigger and had more neurites than those derived from NSCs in the cortex (Kim et al., 2009).

Although fewer neurons are generated, modulating endogenous NSC fate using chemicals or natural products can be another strategy for treating neurodegenerative diseases. Human NSCs are a good source of cells to screen and identify new drugs. However, it is difficult to obtain enough human NSCs from aborted fetal tissue. NSCs from other species, ESCs, or IPSCs have also been used successfully as platforms for drug screening (Bahmad et al., 2017). Identification and culture of mouse ESCs began in the early 1980s and human ESC culture was first introduced by Thomson and colleagues in the late 1990s (Evans and Kaufman, 1981; Martin, 1981; Thomson et al., 1998). Since then, much effort has been dedicated to identify the conditions for generating specific functional types of neurons, such as DA neurons and motor neurons (Cooper et al., 2010; Du et al., 2015). However, because of the disadvantages of human ESCs for regenerative medicine such as immune rejection, approaches to overcome their limitations have been investigated. By introducing ESC-specific genes, such as those encoding SOX2, cMYC, OCT3/4, and KLF4, somatic cells can be converted into cells that possess ESC features, which are referred to as IPSCs (Takahashi and Yamanaka, 2006). This breakthrough study revolutionized research to identify the detailed mechanisms of neurodegenerative diseases because disease cell models could be established and studied by generating IPSCs using somatic cells from patients (Sances et al., 2016). For example, disease-specific IPSCs from patients with PD, HD, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) have been generated successfully (Ebert et al., 2009; Alves et al., 2015; Kikuchi et al., 2017; Vigont et al., 2018). IPSCs generated from individuals with SMA differentiated into motor neurons and astrocytes normally at early time points, but motor neurons were not generated and did not survive efficiently at later time points in the experiments, which recapitulates the disease status (Ebert et al., 2009). This confirms the concept that IPSCs can be used as a model to screen drug candidates.

Neurodegenerative diseases are caused by neuronal damage or loss. Thus, it is important to identify mechanisms through which NSCs differentiate into neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes. The development of drugs that can regulate NSC fate and facilitate the generation of neurons or glia that aid the proper function of neurons is important for therapeutic applications.

NATURAL PRODUCTS THAT MODULATE NSC FATE

Natural products are important sources for developing therapeutic medicines. The contribution of natural products to new drug discovery should not be overlooked. For example, the first statin to be used to reduce cholesterol in blood by inhibiting 3-hydroxy-3-methyl-glutaryl-CoA (HMG-CoA) reductase was developed from Penicillium citrinum (Endo et al., 1976). In addition, the widely-used aspirin is a synthetic molecule modified from salicin, an active ingredient in willow bark, and has long been used to reduce fever, inflammation, and clot formation.

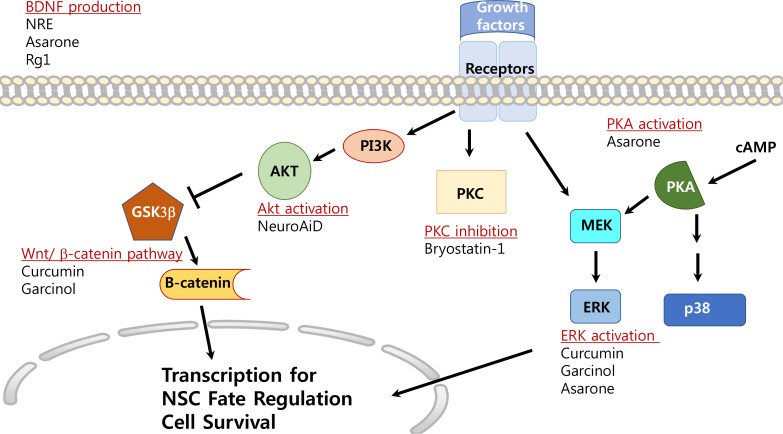

Differentiation of NSCs into neurons occurs only during early development, and many synthetic chemical compounds and natural products are known to control NSC fate (Kim and Jin, 2012; Yoon et al., 2013; Kong et al., 2015; Lee et al., 2016). Natural products may have advantages over synthetic compounds because they may possess an innate stereochemistry that allows them to fit into the protein binding pockets and serve as substrates (Harvey et al., 2015). Because natural products are generated from living organisms, they may have additional biological benefits (Harvey et al., 2015). This review focuses on natural products that regulate NSC fate (Table 1, Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Natural products that regulate NSC fate

| Name | Plant origin | Effects in NSCs | Refs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Asarone | Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii | Increases NSC proliferation and induces neurogenesis | Mao et al., 2015 |

| Bryostatin-1 | Bugula neritina | Increases neurogenesis Promotes differentiation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells Reduces inflammation |

Safaeinejad et al., 2018 |

| Casticin | Croton betulaster | Increases neurogenesis and oligodendrocytogenesis Exerts anti-cancer effect Exerts anti-inflammatory effect |

de Sampaio e Spohr et al., 2010; Chou et al., 2018; Liou et al., 2018 |

| Curcumin | Curcuma longa | Increases neurogenesis Increases proliferation of NSCs Detects amyloid-β |

Garcia-Alloza et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008; Liao et al., 2012; Tiwari et al., 2014, 2016; Wang et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018b; |

| Garcinol | Garcinia indica | Induces neurogenesis Induces cancer cell death |

Weng et al., 2011; Zhou et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2018 |

| Ginkgo biloba extract | Ginkgo biloba | Provides neuroprotection Improves cardiovascular activity and cognitive function Increases neurogenesis |

Tchantchou et al., 2007; Wang and Han, 2015; Osman et al., 2016; Tian et al., 2017; Yuan et al., 2017 |

| Ginsenoside Rg1 | Panax notoginseng | Increases neurogenesis in adipose-derived SCs through miRNA-124 Improves cognitive function Exerts anti-depressant effects Increases neurogenesis |

Jiang et al., 2012; Wu et al., 2013; Dong et al., 2017; Chen et al., 2018a |

| Ginsenoside Rg5 | Panax notoginseng | Increases neurogenesis and decreases astrocytogenesis Ca2+ channel blocker inhibits the neurogenesis of Rg5 |

Liu et al., 2007 |

| Kuwanon V | Morus bombycis | Increases neurogenesis Blocks proliferation Overcomes proliferation signal induced by mitogens Increases cell survival |

Kong et al., 2015 |

| Nelumbo nucifera rhizome extract | Nelumbo nucifera | Increases NSCs and immature neurons | Yang et al., 2008; Yoo et al., 2011 |

| NeuroAiD | Increases neurogenesis and cell proliferation | Heurteaux et al., 2010; Chan and Stanton, 2016 | |

| Phloroglucinol | Hypericum longistylum | Induces differentiation of NSCs, particularly into serotonergic neurons | Wang et al., 2018 |

| Salvia miltiorrhiza | Salvia miltiorrhiza | Increases NSCs and induce neurogenesis Facilitates functional recovery in ischemic model |

Shu et al., 2014 |

| Tenuigenin | Polygala tenuifolia | Promotes NSC proliferation and increases neurogenesis Exerts anti-inflammatory effect |

Chen et al., 2012; Yuan et al., 2012; Fan et al., 2017 |

| Walnut oil | Juglans regia | Induces mesenchymal stem cell line differentiation into neurons | Singh and Sherpa, 2017 |

Fig. 2.

Possible signal transduction mechanisms of natural products for induction of neurogenesis other than anti-oxidative effects and anti-inflammatory effects. Extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERKs), Protein kinase A (PKA), Akt, WNT/β-catenin, PKC and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) pathways/signals are involved in the neuroprotection and neurogenesis of natural products listed in this review.

Asarone, an active component of Rhizoma Acori tatarinowii, is reported to enhance the proliferation of mouse hippocampal NSCs and to promote neurogenesis (Mao et al., 2015). Extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) activation appears to be critical for its ability to induce neurogenesis and proliferation (Mao et al., 2015). When α-asarone or β-asarone was administered to PC12 cells with nerve growth factor, elongated neurites were generated through protein kinase A and cAMP-responsive element binding protein activation (Lam et al., 2016). In addition, β-asarone has been reported to increase the expression of brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF), enhance neurogenesis in the hippocampus and recover behavioral functions determined by forced swim and sucrose preference tests in a chronic unpredictable mild stress rat model (Dong et al., 2014).

Bryostatin, a macrolide and natural marine product, is considered to be a neuroprotective agent since it attenuates neuronal death in ischemic brain induced by middle cerebral artery occlusion (MCAO), decreases inflammation, and enhances cognitive function (Tan et al., 2013). Bryostatin-1 is known to have anti-oxidant properties, decreases matrix metalloproteinase (MMP) 1, 3, 9, 11 activity, activates protein kinase C (PKC) with short-term exposure, inhibits PKC with long-term exposure, and promotes neurogenesis and differentiation of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (Kortmansky and Schwartz, 2003; Sun et al., 2008; Safaeinejad et al., 2018). Bryostatin-1 suppresses inflammation by inhibiting inflammation related signals mediated by Th1, one of the various types of T helper cells and by activating Th2, another T helper cell type, that is known to have anti-inflammatory effects both in vitro (bone marrow-derived dendritic cells) and in vivo (adult mice, 6–8 weeks of age) by acting as a Toll-like receptor 4 ligand (Ariza et al., 2011). In mice with experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis, an animal model of multiple sclerosis (MS), Bryostatin-1 cured and prevented neurological defect and reduced inflammation in immune cells (Kornberg et al., 2018). It has been known that MMPs loosen the blood brain barrier and allow increased penetration of inflammatory cells into the CNS (Safaeinejad et al., 2018). MMPs are also reported to increase demyelination in the CNS (Safaeinejad et al., 2018). Co-administration of intravenous Bryostiatin-1 infusion with oral α-tocopherol improved water maze tasks in adult male rats and Bryostatin-1 increased neurogenesis by increasing cell survival and enhanced BDNF activity when administered after cerebral ischemia in rats (Sun and Alkon, 2008; Sun et al., 2008). In the process of screening oligodendrocyte-inducing drugs among PKC inhibitors, Bryostatin-1 promoted oligodendrocyte progenitor cells in the presence of myelin protein extracts which are known to be an inhibitory myelin substrate (Gonzalez et al., 2016). Thus, the decreased activity of MMPs by Brytostatin-1 appears to reduce the spread of inflammation and demyelination in the CNS and provides effective therapeutic effects on MS (Kornberg et al., 2018; Safaeinejad et al., 2018).

Casticin, a flavonoid component of Croton betulaster, increases neurogenesis through neuroprotection without affecting astrocyte and oligodendrocyte populations in rat cortical NPCs (de Sampaio e Spohr et al., 2010). Intriguingly, soluble factors appear to be involved in the neuroprotection-mediated neuronal increase because the neuronal population increased when NPCs were cultured with casticin-treated astrocytes or treated with conditioned media from casticin-treated astrocytes (de Sampaio e Spohr et al., 2010). Additionally, casticin is known to have anti-cancer activity and can induce DNA damage, apoptosis, and G2/M phase arrest (Chou et al., 2018). The anti-inflammatory effects of casticin enable its use in treating asthma: in ovalbumin-induced asthma models of female mice, casticin decreased airway sensitivity and oxidative responses in the lungs (Liou et al., 2018).

Curcumin is a phenolic component from Curcuma longa that has been widely consumed worldwide as a spice (Esatbeyoglu et al., 2012). Curcumin exerts an anti-depressant effect by protecting neurons and promoting hippocampal neurogenesis in chronically stressed rats (Xu et al., 2007). Moreover, curcumin prevents stress-induced reductions of 5-HT1A and BDNF expression (Xu et al., 2007). When aged rats were fed curcumin in the diet for 6 and 12 weeks, DG cell proliferation was enhanced and memory was improved (Dong et al., 2012). Interestingly, curcumin increased the growth of neurites by activating ERKs and protein kinase C in PC12 cells (Liao et al., 2012). It is suggested that curcumin induces neurogenesis via the WNT/β-catenin pathway and increases GSK-3β in bisphenol A-treated rats or celecoxib-treated NPCs or neurons (Tiwari et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2017). In addition, the Notch intracellular domain level increased in MCAO ischemic rats treated with curcumin compared to that in vehicle-treated animals (Liu et al., 2016). Curcumin can also be applied as a diagnostic and/or therapeutic material to detect and disaggregate amyloid-β proteins because it crosses the blood-brain barrier, possesses natural fluorescence, has high affinity for senile plaques, and even clears or reduces the plaques (Garcia-Alloza et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2018b). When curcumin was administered in the form of curcumin-loaded nanoparticles, it induced neurogenesis and NSC proliferation through the WNT/β-catenin pathway in adult rat hippocampus and in cultured NSCs (Tiwari et al., 2014). Inhibiting the WNT pathway using siRNAs or pharmacological blockers reduced curcumin-mediated neurogenesis (Tiwari et al., 2014). Curcumin exhibited concentration-dependent effects in that low concentrations of curcumin stimulated mouse NSC proliferation through ERK and p38 kinases, whereas high concentrations caused cell death (Kim et al., 2008).

Garcinol, found in Garcinia indica fruit rind, activates ERK for up to 20 hours, induces neurogenesis, and promotes neurite outgrowth in cortical NPCs (Weng et al., 2011). Garcinol is also known to induce cancer cell death via down-regulating/inactivating the WNT/β-catenin signaling pathway and inactivating signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (Zhou et al., 2017; Huang et al., 2018).

Ginkgo biloba extract (GBE) has been used as traditional medicine in China and is known to improve cardiovascular activity and cognitive functions including memory, learning, and attention (Tian et al., 2017; Yuan et al., 2017). GBE has neuroprotective effects against amyloid-β- and hypoxia-induced neurotoxicity (Tchantchou et al., 2007). When tested in aged mice (two years old), GBE increased NSC proliferation and the production of doublecortin-positive neurons in the DG (Osman et al., 2016). When NSCs derived from mouse cochlea were treated with GBE, cell survival and neurogenesis were promoted with elongated neurite outgrowth (Wang and Han, 2015), suggesting that GBE may be beneficial for treating hearing loss.

The ginsenoside Rg1 is also known to promote neurogenesis in mouse adipose-derived SCs through miRNA-124 (Dong et al., 2017). When injected in rats along with D-galactose, Rg1 improved the cognitive deficit caused by D-galactose by reducing NSC senescence and oxidative stress (Chen et al., 2018a). Interestingly, Rg1 decreased the phosphorylation levels of protein kinase B and the mechanistic target of rapamycin (Chen et al., 2018a). In mouse models of depression, Rg1 showed anti-depressant-like effects through activating the BDNF signaling pathway and reducing corticosterone serum levels (Jiang et al., 2012). Rg1 reversed dendritic spine density and hippocampal neurogenesis in chronic mild stress mouse models of depression (Jiang et al., 2012). When treated in embryonic bodies, Rg1 induced neuron-like cells and neuron markers including neurofilament and β-tubulin III (Wu et al., 2013).

The panaxadiol glycosides Rg5, Rk1, and Rg3 were found to induce neurogenesis in epithermal growth factor-responsive NSCs (Liu et al., 2007). Rg5-induced neurogenesis at the expense of astrogliogenesis and neurogenesis was blocked when the Ca2+ channel antagonist nifedipine was used.

Kuwanon V (KWV), a phenolic compound found in the roots of the mulberry tree (Morus bombycis), is known to increase neurogenesis in rat NSCs (Kong et al., 2015). Interestingly, the neurogenic effect of KWV is strong enough to overcome the proliferation signals induced by growth factors; KWV induces neurogenesis not only during differentiation, but also during proliferation of NSCs (Kong et al., 2015). KWV inhibited NSC proliferation but did not affect astrocytogenesis (Kong et al., 2015). Although the detailed effects on the regulation of NSC fate are not known, the components isolated from the root of Morus species including cyclomulberrin, sanggenon I, morusin, KWU, KWE, moracin P, moracin O, and mulberrofuran Q, have been reported to increase survival of neurons (Lee et al., 2011, 2012). Interestingly, moracenin D from Mori Cortex Radicis induced NURR1 expression but repressed α-synuclein mRNA expression and resulted in the protection of SH-SY5Y cells with a high dopamine concentration, suggesting that natural products in the Morus species are effective in regulating neural activity and survival (Ham et al., 2012).

Nelumbo nucifera rhizome extract (NRE) increased cell proliferation and doublecortin (an immature neuronal marker)-positive cell number in rats with scopolamine-induced amnesia (Yoo et al., 2011). In addition, NRE reinstated the decreased BDNF levels caused by scopolamine (Yoo et al., 2011). Moreover, NRE significantly increased memory function determined by a step-through passive avoidance test and neurogenesis through activating NSC proliferation and differentiation in rat DG (Yang et al., 2008).

NeuroAiD (MLC601 or MLC901) is a mixture of plant and animal derivatives and is used as traditional medicine in China to treat patients with strokes because it improves survival and behavioral function after ischemia (Heurteaux et al., 2010). MLC601 is a mixture of 9 plant components (radix astragali, radix salviae mitorrhizae, radix paeoniae rubrae, rhizoma chuan-xiong, radix angelicae sinensis, Carthamus tinctorius, Prunus persica, radix polygalae and rhizoma acori tata-rinowii) and 5 animal components (including Hirudo, Eupolyphaga seu Steleophaga, calculus bovis artifactus, Buthus martensii and Cornu saigae tataricae) (Heurteaux et al., 2013). MLC901 is used in Europe and is a simplified version that contain 9 plant components (Heurteaux et al., 2013). In global ischemic model rats, MLC901 decreased cell death, increased the numbers of newly generated neurons, and improved behavioral function which are mediated by reduction of BAX expression and AKT activation (Quintard et al., 2011). NeuroAiD also increases neurogenesis, promotes cell proliferation, and induces neurite outgrowth in rodent and human cells (Heurteaux et al., 2010). In human NPCs, microarray experiments revealed genes regulated by MLC901 and identified FGF19, FGF3, and others as potential targets for neurogenesis (Chan and Stanton, 2016).

Phloroglucinol derivatives from Hypericum longistylum are known to facilitate the differentiation of NPCs derived from ESCs, while particularly increasing serotonergic neurogenesis (Wang et al., 2018). The components of Hypericum longistylum have been suggested to function as protein tyrosine phosphatase 1B inhibitors and have potential to treat type II diabetes (Cao et al., 2017). Hypericum longistylum has long been used to cure depression in China, which may be attributed to the effects of the phloroglucinol derivatives (Wang et al., 2018).

Salvia miltiorrhiza (derived from the plant Salvia miltiorrhiza), a type of Chinese medicine, is known to have antioxidative and anti-inflammatory activities and has been used to treat neurological diseases (Bonaccini et al., 2015). When IPSCs were treated with Salvia miltiorrhiza, the NSC marker NES expression was increased and neurogenesis was induced (Shu et al., 2014). After Salvia miltiorrhiza was administered into rats with MCAO ischemic brain tissue, the treated rats had more neurons and showed better functional recovery (Shu et al., 2014). Depsides and tanshiones, the component of Salvia miltiorrhiza, are also known to be effective in memory improvement and cell survival in animal models of cerebral ischemia and AD (Mei et al., 2009; Bonaccini et al., 2015).

Tenuigenin, a component of Polygala tenuifolia, is reported to possess anti-inflammatory activity and protects DA neurons, possibly by suppressing activation of the pyrin domain-containing 3 inflammasome (Yuan et al., 2012; Fan et al., 2017). When tenuigenin was treated in neurosphere cultures of hippocampal NSCs, it promoted NSC proliferation as determined by bromodeoxyuridine, a thymidine analogue that is inserted into DNA during replication, assay and differentiation into neurons and astrocytes (Chen et al., 2012).

Walnut (Juglans regia L.) oil induces the differentiation of C3H10T1/2 cells, a murine mesenchymal stem cell line, into neuron-like cells with long outgrowths of axon-like structures (Singh and Sherpa, 2017). Homolocarpum seed oil, which is known to contain high amounts of α-linolenic acid, β-sitosterol, and campesterol, resulted in increased neurosphere formation when administered to adult male BALB/c mice without affecting in vitro differentiation of the harvested NSCs (Hamedi et al., 2015).

The detailed mechanisms of how natural products induce NSC proliferation or differentiation are not yet known. Some studies revealed that phytochemicals alter signal transduction such as ERK activation or WNT/β-catenin signaling. Recent evidence suggests that these signals not only influence gene transcription, but also epigenetic modification and regulation of SC fate (Kim, 2011; Kong et al., 2018). For example, histone proteins have long been considered scaffold proteins that help to contain DNA within the limited space of the nucleus, but recently their active role in controlling transcription by regulating the accessibility of genes to transcription factors has been revealed (Kim and Rosenfeld, 2010; Kim, 2011; Rothbart and Strahl, 2014). It would be of great interest to find common mechanisms of neurogenesis induction by natural products, if any exist, and apply them in a medicinal context to regenerate neurons that are lost in neurodegenerative diseases.

CONCLUSIONS

NSCs derived from embryos, ESCs, or IPSCs are good platforms to screen drugs that can increase neurogenesis or control NSC fate. Several phytochemicals have been reported to control NSC fate. Since specific types of neurons are lost in neurodegenerative diseases, phytochemicals that can regenerate neurons would be important for therapeutic applications. Although the detailed underlying mechanisms are not clearly known, natural products hold promise for the development of new drugs to treat neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the National Research Foundation of Korea grant number [NRF2017R1A1A1A05000876] and supported by the Chung-Ang University Research Grant in [2016–2017] (granted to H-J. K.).

Apologies are extended to authors who carried out research on NSCs with natural products but whose studies have not been mentioned and included in this review because of the limitations of the author’s knowledge. I thank Lee HR for helping illustration.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Akhtar AA, Gowing G, Kobritz N, Savinoff SE, Garcia L, Saxon D, Cho N, Kim G, Tom CM, Park H, Lawless G, Shelley BC, Mattis VB, Breunig JJ, Svendsen CN. Inducible expression of GDNF in transplanted iPSC-derived neural progenitor cells. Stem Cell Reports. 2018;10:1696–1704. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2018.03.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman J, Das GD. Autoradiographic and histological evidence of postnatal hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. J. Comp. Neurol. 1965;124:319–335. doi: 10.1002/cne.901240303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alves CJ, Dariolli R, Jorge FM, Monteiro MR, Maximino JR, Martins RS, Strauss BE, Krieger JE, Callegaro D, Chadi G. Gene expression profiling for human iPS-derived motor neurons from sporadic ALS patients reveals a strong association between mitochondrial functions and neurodegeneration. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2015;9:289. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ariza ME, Ramakrishnan R, Singh NP, Chauhan A, Nagarkatti PS, Nagarkatti M. Bryostatin-1, a naturally occurring antineoplastic agent, acts as a Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR-4) ligand and induces unique cytokines and chemokines in dendritic cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:24–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.135921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bahmad H, Hadadeh O, Chamaa F, Cheaito K, Darwish B, Makkawi AK, Abou-Kheir W. Modeling human neurological and neurodegenerative diseases: from induced pluripotent stem cells to neuronal differentiation and its applications in neurotrauma. Front. Mol. Neurosci. 2017;10:50. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonaccini L, Karioti A, Bergonzi MC, Bilia AR. Effects of salvia miltiorrhiza on CNS neuronal injury and degeneration: a plausible complementary role of tanshinones and depsides. Planta Med. 2015;81:1003–1016. doi: 10.1055/s-0035-1546196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury J. Molecular insights into human brain evolution. PLoS Biol. 2005;3:e50. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0030050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao X, Yang X, Wang P, Liang Y, Liu F, Tuerhong M, Jin DQ, Xu J, Lee D, Ohizumi Y, Guo Y. Polycyclic phloroglucinols as PTP1B inhibitors from Hypericum longistylum: structures, PTP1B inhibitory activities, and interactions with PTP1B. Bioorg. Chem. 2017;75:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2017.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cha KJ, Kong SY, Lee JS, Kim HW, Shin JY, La M, Han BW, Kim DS, Kim HJ. Cell density-dependent differential proliferation of neural stem cells on omnidirectional nanopore-arrayed surface. Sci. Rep. 2017;7:13077. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-13372-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan HY, Stanton LW. A pharmacogenomic profile of human neural progenitors undergoing differentiation in the presence of the traditional Chinese medicine NeuroAiD. Pharmacogenomics J. 2016;16:461–471. doi: 10.1038/tpj.2016.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JY, Wang EA, Cepeda C, Levine MS. Dopamine imbalance in Huntington’s disease: a mechanism for the lack of behavioral flexibility. Front. Neurosci. 2013;7:114. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2013.00114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Yao H, Chen X, Wang Z, Xiang Y, Xia J, Liu Y, Wang Y. Ginsenoside Rg1 decreases oxidative stress and down-regulates akt/mtor signalling to attenuate cognitive impairment in mice and senescence of neural stem cells induced by D-galactose. Neurochem. Res. 2018a;43:430–440. doi: 10.1007/s11064-017-2438-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M, Du ZY, Zheng X, Li DL, Zhou RP, Zhang K. Use of curcumin in diagnosis, prevention, and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Neural. Regen. Res. 2018b;13:742–752. doi: 10.4103/1673-5374.230303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen Y, Huang X, Chen W, Wang N, Li L. Tenuigenin promotes proliferation and differentiation of hippocampal neural stem cells. Neurochem. Res. 2012;37:771–777. doi: 10.1007/s11064-011-0671-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chou GL, Peng SF, Liao CL, Ho HC, Lu KW, Lien JC, Fan MJ, La KC, Chung JG. Casticin impairs cell growth and induces cell apoptosis via cell cycle arrest in human oral cancer SCC-4 cells. Environ. Toxicol. 2018;33:127–141. doi: 10.1002/tox.22497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cieslar-Pobuda A, Knoflach V, Ringh MV, Stark J, Likus W, Siemianowicz K, Ghavami S, Hudecki A, Green JL, Los MJ. Transdifferentiation and reprogramming: overview of the processes, their similarities and differences. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2017;1864:1359–1369. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2017.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper O, Hargus G, Deleidi M, Blak A, Osborn T, Marlow E, Lee K, Levy A, Perez-Torres E, Yow A, Isacson O. Differentiation of human ES and Parkinson’s disease iPS cells into ventral midbrain dopaminergic neurons requires a high activity form of SHH, FGF8a and specific regionalization by retinoic acid. Mol. Cell Neurosci. 2010;45:258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2010.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dar KB, Bhat AH, Amin S, Masood A, Zargar MA, Ganie SA. Inflammation: a multidimensional insight on natural anti-inflammatory therapeutic compounds. Curr. Med. Chem. 2016;23:3775–3800. doi: 10.2174/0929867323666160817163531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Sampaio e Spohr TC, Stipursky J, Sasaki AC, Barbosa PR, Martins V, Benjamim CF, Roque NF, Costa SL, Gomes FC. Effects of the flavonoid casticin from Brazilian Croton betulaster in cerebral cortical progenitors in vitro: direct and indirect action through astrocytes. J. Neurosci. Res. 2010;88:530–541. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H, Gao Z, Rong H, Jin M, Zhang X. beta-asarone reverses chronic unpredictable mild stress-induced depression-like behavior and promotes hippocampal neurogenesis in rats. Molecules. 2014;19:5634–5649. doi: 10.3390/molecules19055634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Zhu G, Wang TC, Shi FS. Ginsenoside Rg1 promotes neural differentiation of mouse adipose-derived stem cells via the miRNA-124 signaling pathway. J. Zhejiang Univ. Sci. B. 2017;18:445–448. doi: 10.1631/jzus.B1600355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong S, Zeng Q, Mitchell ES, Xiu J, Duan Y, Li C, Tiwari JK, Hu Y, Cao X, Zhao Z. Curcumin enhances neurogenesis and cognition in aged rats: implications for transcriptional interactions related to growth and synaptic plasticity. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e31211. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du ZW, Chen H, Liu H, Lu J, Qian K, Huang CL, Zhong X, Fan F, Zhang SC. Generation and expansion of highly pure motor neuron progenitors from human pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6626. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ebert AD, Yu J, Rose FF, Jr, Mattis VB, Lorson CL, Thomson JA, Svendsen CN. Induced pluripotent stem cells from a spinal muscular atrophy patient. Nature. 2009;457:277–280. doi: 10.1038/nature07677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Endo A, Masao K, Tsujita Y. ML-236A, ML-236B, and ML-236C, new inhibitors of cholesterogenesis produced by Penicillium Citrium. J. Antibiot. 1976;29:1346–1348. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.29.1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Bjork-Eriksson T, Alborn AM, Nordborg C, Peterson DA, Gage FH. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat. Med. 1998;4:1313–1317. doi: 10.1038/3305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esatbeyoglu T, Huebbe P, Ernst IM, Chin D, Wagner AE, Rimbach G. Curcumin--from molecule to biological function. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 2012;51:5308–5332. doi: 10.1002/anie.201107724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans MJ, Kaufman MH. Establishment in culture of pluripotential cells from mouse embryos. Nature. 1981;292:154–156. doi: 10.1038/292154a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Z, Liang Z, Yang H, Pan Y, Zheng Y, Wang X. Tenuigenin protects dopaminergic neurons from inflammation via suppressing NLRP3 inflammasome activation in microglia. J. Neuroinflammation. 2017;14:256. doi: 10.1186/s12974-017-1036-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gage FH. Mammalian neural stem cells. Science. 2000;287:1433–1438. doi: 10.1126/science.287.5457.1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Alloza M, Borrelli LA, Rozkalne A, Hyman BT, Bacskai BJ. Curcumin labels amyloid pathology in vivo, disrupts existing plaques, and partially restores distorted neurites in an Alzheimer mouse model. J. Neurochem. 2007;102:1095–1104. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04613.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goncalves JT, Schafer ST, Gage FH. Adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus: from stem cells to behavior. Cell. 2016;167:897–914. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez GA, Hofer MP, Syed YA, Amaral AI, Rundle J, Rahman S, Zhao C, Kotter MR. Tamoxifen accelerates the repair of demyelinated lesions in the central nervous system. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:31599. doi: 10.1038/srep31599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ham A, Lee HJ, Hong SS, Lee D, Mar W. Moracenin D from Mori Cortex radicis protects SH-SY5Y cells against dopamine-induced cell death by regulating nurr1 and alpha-synuclein expression. Phytother. Res. 2012;26:620–624. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamedi A, Ghanbari A, Razavipour R, Saeidi V, Zarshenas MM, Sohrabpour M, Azari H. Alyssum homolocarpum seeds: phytochemical analysis and effects of the seed oil on neural stem cell proliferation and differentiation. J. Nat. Med. 2015;69:387–396. doi: 10.1007/s11418-015-0905-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey AL, Edrada-Ebel R, Quinn RJ. The re-emergence of natural products for drug discovery in the genomics era. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2015;14:111–129. doi: 10.1038/nrd4510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heurteaux C, Gandin C, Borsotto M, Widmann C, Brau F, Lhuillier M, Onteniente B, Lazdunski M. Neuroprotective and neuroproliferative activities of NeuroAid (MLC601, MLC901), a Chinese medicine, in vitro and in vivo. Neuropharmacology. 2010;58:987–1001. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2010.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heurteaux C, Widmann C, Moha ou Maati H, Quintard H, Gandin C, Borsotto M, Veyssiere J, Onteniente B, Lazdunski M. NeuroAiD: properties for neuroprotection and neurorepair. Cerebrovasc. Dis. 2013;35(Suppl 1):1–7. doi: 10.1159/000346228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang WC, Kuo KT, Adebayo BO, Wang CH, Chen YJ, Jin K, Tsai TH, Yeh CT. Garcinol inhibits cancer stem cell-like phenotype via suppression of the Wnt/beta-catenin/STAT3 axis signalling pathway in human non-small cell lung carcinomas. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018;54:140–150. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2017.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang B, Xiong Z, Yang J, Wang W, Wang Y, Hu ZL, Wang F, Chen JG. Antidepressant-like effects of ginsenoside Rg1 are due to activation of the BDNF signalling pathway and neurogenesis in the hippocampus. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2012;166:1872–1887. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2012.01902.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi T, Morizane A, Doi D, Okita K, Nakagawa M, Yamakado H, Inoue H, Takahashi R, Takahashi J. Idiopathic Parkinson’s disease patient-derived induced pluripotent stem cells function as midbrain dopaminergic neurons in rodent brains. J. Neurosci. Res. 2017;95:1829–1837. doi: 10.1002/jnr.24014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ. Stem cell potential in Parkinson’s disease and molecular factors for the generation of dopamine neurons. Biochim. BiophysActa. 2011;1812:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2010.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Jin CY. Stem cells in drug screening for neurodegenerative disease. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2012;16:1–9. doi: 10.4196/kjpp.2012.16.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, McMillan E, Han F, Svendsen CN. Regionally specified human neural progenitor cells derived from the mesencephalon and forebrain undergo increased neurogenesis following overexpression of ASCL1. Stem Cells. 2009;27:390–398. doi: 10.1634/stemcells.2007-1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HJ, Rosenfeld MG. Epigenetic control of stem cell fate to neurons and glia. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2010;33:1467–1473. doi: 10.1007/s12272-010-1001-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Sim J, Kim HJ. Neural stem cell differentiation using microfluidic device-generated growth factor gradient. Biomol. Ther. (Seoul) 2018;26:380–388. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2018.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim SJ, Son TG, Park HR, Park M, Kim MS, Kim HS, Chung HY, Mattson MP, Lee J. Curcumin stimulates proliferation of embryonic neural progenitor cells and neurogenesis in the adult hippocampus. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:14497–14505. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M708373200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong SY, Kim W, Lee HR, Kim HJ. The histone demethylase KDM5A is required for the repression of astrocytogenesis and regulated by the translational machinery in neural progenitor cells. FASEB J. 2018;32:1108–1119. doi: 10.1096/fj.201700780R. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong SY, Park MH, Lee M, Kim JO, Lee HR, Han BW, Svendsen CN, Sung SH, Kim HJ. Kuwanon V inhibits proliferation, promotes cell survival and increases neurogenesis of neural stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0118188. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornberg MD, Smith MD, Shirazi HA, Calabresi PA, Snyder SH, Kim PM. Bryostatin-1 alleviates experimental multiple sclerosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2018;115:2186–2191. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1719902115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kortmansky J, Schwartz GK. Bryostatin-1: a novel PKC inhibitor in clinical development. Cancer Invest. 2003;21:924–936. doi: 10.1081/CNV-120025095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lam KY, Chen J, Lam CT, Wu Q, Yao P, Dong TT, Lin H, Tsim KW. Asarone from Acori Tatarinowii Rhizoma potentiates the nerve growth factor-induced neuronal differentiation in cultured PC12 cells: a signaling mediated by protein kinase. A. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0163337. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0163337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Lyu da H, Koo U, Lee SJ, Hong SS, Kim K, Kim KH, Lee D, Mar W. Inhibitory effect of 2-arylbenzofurans from the Mori Cortex Radicis (Moraceae) on oxygen glucose deprivation (OGD)-induced cell death of SH-SY5Y cells. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2011;34:1373–1380. doi: 10.1007/s12272-011-0818-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HJ, Lyu da H, Koo U, Nam KW, Hong SS, Kim KO, Kim KH, Lee D, Mar W. Protection of prenylated flavonoids from Mori Cortex Radicis (Moraceae) against nitric oxide-induced cell death in neuroblastoma SH-SY5Y cells. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2012;35:163–170. doi: 10.1007/s12272-012-0118-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HR, Farhanullah, Lee J., Jajoo R., Kong SY, Shin JY, Kim JO, Lee J, Lee J, Kim HJ. Discovery of a small molecule that enhances astrocytogenesis by activation of STAT3, SMAD1/5/8, and ERK1/2 via induction of cytokines in neural stem cells. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2016;7:90–99. doi: 10.1021/acschemneuro.5b00243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao KK, Wu MJ, Chen PY, Huang SW, Chiu SJ, Ho CT, Yen JH. Curcuminoids promote neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells through MAPK/ERK- and PKC-dependent pathways. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2012;60:433–443. doi: 10.1021/jf203290r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liou CJ, Cheng CY, Yeh KW, Wu YH, Huang WC. Protective effects of casticin from vitex trifolia alleviate eosinophilic airway inflammation and oxidative stress in a murine asthma model. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:635. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu JW, Tian SJ, de Barry J, Luu B. Panaxadiol glycosides that induce neuronal differentiation in neurosphere stem cells. J. Nat. Prod. 2007;70:1329–1334. doi: 10.1021/np070135j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Cao Y, Qu M, Zhang Z, Feng L, Ye Z, Xiao M, Hou ST, Zheng R, Han Z. Curcumin protects against stroke and increases levels of Notch intracellular domain. Neurol. Res. 2016;38:553–559. doi: 10.1080/01616412.2016.1187804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mao J, Huang S, Liu S, Feng XL, Yu M, Liu J, Sun YE, Chen G, Yu Y, Zhao J, Pei G. A herbal medicine for Alzheimer’s disease and its active constituents promote neural progenitor proliferation. Aging Cell. 2015;14:784–796. doi: 10.1111/acel.12356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin GR. Isolation of a pluripotent cell line from early mouse embryos cultured in medium conditioned by teratocarcinoma stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1981;78:7634–7638. doi: 10.1073/pnas.78.12.7634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald ME, Ambrose CM, Duyao MP, Myers HR, Lin C, Srinidhi L, Barnes G, Taylor SA, James M, Groot N, MacFarlane H, Jenkins B, Anderson MA, Wexler NS, Gusella JF, Bates GP, Baxendale S, Hummerich H, Kirby S, North M, Youngman S, Mott R, Zehetner G, Sedlacek Z, Poustka A, Frischauf A.-M, Lehrach H, Buckler AJ, Church D, Doucette-Stamm L, O’Donovan MC, Riba-Ramirez L, Shah M, Stanton VP, Strobel SA, Draths KM, Wales JL, Dervan P, Housman DE, Altherr M, Shiang R, Thompson L, Fielder T, Wasmuth JJ, Tagle D, Valdes J, Elmer L, Allard M, Castilla L, Swaroop M, Blanchard K, Collins FS, Snell R, Holloway T, Gillespie K, Datson N, Shaw D, Harper PS. A novel gene containing a trinucleotide repeat that is expanded and unstable on Huntington’s disease chromosomes. Cell. 1993;72:971–983. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90585-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mei Z, Zhang F, Tao L, Zheng W, Cao Y, Wang Z, Tang S, Le K, Chen S, Pi R, Liu P. Cryptotanshinone, a compound from Salvia miltiorrhiza modulates amyloid precursor protein metabolism and attenuates beta-amyloid deposition through upregulating alpha-secretase in vivo and in vitro. Neurosci. Lett. 2009;452:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroy A, Lithgow GJ, Alavez S. Curcumin and neurodegenerative diseases. Biofactors. 2013;39:122–132. doi: 10.1002/biof.1063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman NM, Amer AS, Abdelwahab S. Effects of Ginko biloba leaf extract on the neurogenesis of the hippocampal dentate gyrus in the elderly mice. Anat. Sci. Int. 2016;91:280–289. doi: 10.1007/s12565-015-0297-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredes MF, Sorrells SF, Garcia-Verdugo JM, Alvarez-Buylla A. Brain size and limits to adult neurogenesis. J. Comp. Neurol. 2016;524:646–664. doi: 10.1002/cne.23896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintard H, Borsotto M, Veyssiere J, Gandin C, Labbal F, Widmann C, Lazdunski M, Heurteaux C. MLC901, a traditional Chinese medicine protects the brain against global ischemia. Neuropharmacology. 2011;61:622–631. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds BA, Tetzlaff W, Weiss S. A multipotent EGF-responsive striatal embryonic progenitor cell produces neurons and astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 1992;12:4565–4574. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.12-11-04565.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds BA, Weiss S. Generation of neurons and astrocytes from isolated cells of the adult mammalian central nervous system. Science. 1992;255:1707–1710. doi: 10.1126/science.1553558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbart SB, Strahl BD. Interpreting the language of histone and DNA modifications. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2014;1839:627–643. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Safaeinejad F, Bahrami S, Redl H, Niknejad H. Inhibition of inflammation, suppression of matrix metalloproteinases, induction of neurogenesis, and antioxidant property make bryostatin-1 a therapeutic choice for multiple sclerosis. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:625. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sances S, Bruijn LI, Chandran S, Eggan K, Ho R, Klim JR, Livesey MR, Lowry E, Macklis JD, Rushton D, Sadegh C, Sareen D, Wichterle H, Zhang SC, Svendsen CN. Modeling ALS with motor neurons derived from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Nat. Neurosci. 2016;19:542–553. doi: 10.1038/nn.4273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvageot CM, Stiles CD. Molecular mechanisms controlling cortical gliogenesis. Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 2002;12:244–249. doi: 10.1016/S0959-4388(02)00322-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider BL, Seehus CR, Capowski EE, Aebischer P, Zhang SC, Svendsen CN. Over-expression of alpha-synuclein in human neural progenitors leads to specific changes in fate and differentiation. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2007;16:651–666. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shal B, Ding W, Ali H, Kim YS, Khan S. Anti-neuroinflammatory potential of natural products in attenuation of Alzheimer’s disease. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:548. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin JY, Kong SY, Yoon HJ, Ann J, Lee J, Kim HJ. An aminopropyl carbazole derivative induces neurogenesis by increasing final cell division in neural stem cells. Biomol. Ther. (Seoul) 2015;23:313–319. doi: 10.4062/biomolther.2015.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shu T, Pang M, Rong L, Zhou W, Wang J, Liu C, Wang X. Effects of Salvia miltiorrhiza on neural differentiation of induced pluripotent stem cells. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014;153:233–241. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2014.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh V, Sherpa M. Neuronal-like differentiation of murine mesenchymal stem cell line: stimulation by Juglans regia L. oil. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2017;183:385–395. doi: 10.1007/s12010-017-2452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun MK, Alkon DL. Synergistic effects of chronic bryostatin-1 and alpha-tocopherol on spatial learning and memory in rats. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 2008;584:328–337. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2008.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun MK, Hongpaisan J, Nelson TJ, Alkon DL. Poststroke neuronal rescue and synaptogenesis mediated in vivo by protein kinase C in adult brains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2008;105:13620–13625. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0805952105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi K, Yamanaka S. Induction of pluripotent stem cells from mouse embryonic and adult fibroblast cultures by defined factors. Cell. 2006;126:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Z, Turner RC, Leon RL, Li X, Hongpaisan J, Zheng W, Logsdon AF, Naser ZJ, Alkon DL, Rosen CL, Huber JD. Bryostatin improves survival and reduces ischemic brain injury in aged rats after acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2013;44:3490–3497. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tchantchou F, Xu Y, Wu Y, Christen Y, Luo Y. EGb 761 enhances adult hippocampal neurogenesis and phosphorylation of CREB in transgenic mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease. FASEB J. 2007;21:2400–2408. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7649com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson JA, Itskovitz-Eldor J, Shapiro SS, Waknitz MA, Swiergiel JJ, Marshall VS, Jones JM. Embryonic stem cell lines derived from human blastocysts. Science. 1998;282:1145–1147. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5391.1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian J, Liu Y, Chen K. Ginkgo biloba extract in vascular protection: molecular mechanisms and clinical applications. Curr. Vasc. Pharmacol. 2017;15:532–548. doi: 10.2174/1570161115666170713095545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari SK, Agarwal S, Seth B, Yadav A, Nair S, Bhatnagar P, Karmakar M, Kumari M, Chauhan LK, Patel DK, Srivastava V, Singh D, Gupta SK, Tripathi A, Chaturvedi RK, Gupta KC. Curcumin-loaded nanoparticles potently induce adult neurogenesis and reverse cognitive deficits in Alzheimer’s disease model via canonical Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. ACS Nano. 2014;8:76–103. doi: 10.1021/nn405077y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari SK, Agarwal S, Tripathi A, Chaturvedi RK. Bisphenol-A mediated inhibition of hippocampal neurogenesis attenuated by curcumin via canonical Wnt pathway. Mol. Neurobiol. 2016;53:3010–3029. doi: 10.1007/s12035-015-9197-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vigont V, Nekrasov E, Shalygin A, Gusev K, Klushnikov S, Illarioshkin S, Lagarkova M, Kiselev SL, Kaznacheyeva E. Patient-specific iPSC-based models of Huntington’s disease as a tool to study store-operated calcium entry drug targeting. Front. Pharmacol. 2018;9:696. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2018.00696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang C, Han Z. Ginkgo biloba extract enhances differentiation and performance of neural stem cells in mouse cochlea. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2015;35:861–869. doi: 10.1007/s10571-015-0180-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H, Zhang W, Gao Q, Cao X, Li Y, Li X, Min Z, Yu Y, Guo Y, Shuai L. Extractive from Hypericum ascyron L promotes serotonergic neuronal differentiation in vitro. Stem Cell Res. 2018;31:42–50. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2018.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang R, Tian S, Yang X, Liu J, Wang Y, Sun K. Celecoxib-induced inhibition of neurogenesis in fetal frontal cortex is attenuated by curcumin via Wnt/beta-catenin pathway. Life Sci. 2017;185:95–102. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2017.07.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weng MS, Liao CH, Yu SY, Lin JK. Garcinol promotes neurogenesis in rat cortical progenitor cells through the duration of extracellular signal-regulated kinase signaling. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011;59:1031–1040. doi: 10.1021/jf104263s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Pan Z, Cheng M, Shen Y, Yu H, Wang Q, Lou Y. Ginsenoside Rg1 facilitates neural differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells via GR-dependent signaling pathway. Neurochem. Int. 2013;62:92–102. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2012.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y, Ku B, Cui L, Li X, Barish PA, Foster TC, Ogle WO. Curcumin reverses impaired hippocampal neurogenesis and increases serotonin receptor 1A mRNA and brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression in chronically stressed rats. Brain Res. 2007;1162:9–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2007.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang WM, Shim KJ, Choi MJ, Park SY, Choi BJ, Chang MS, Park SK. Novel effects of Nelumbo nucifera rhizome extract on memory and neurogenesis in the dentate gyrus of the rat hippocampus. Neurosci. Lett. 2008;443:104–107. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoo DY, Kim W, Yoo KY, Lee CH, Choi JH, Kang IJ, Yoon YS, Kim DW, Won MH, Hwang IK. Effects of Nelumbo nucifera rhizome extract on cell proliferation and neuroblast differentiation in the hippocampal dentate gyrus in a scopolamine-induced amnesia animal model. Phytother. Res. 2011;25:809–815. doi: 10.1002/ptr.3337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoon HJ, Kong SY, Park MH, Cho Y, Kim SE, Shin JY, Jung S, Lee J, Farhanullah Kim, H. J, Lee J. Aminopropyl carbazole analogues as potent enhancers of neurogenesis. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2013;21:7165–7174. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2013.08.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan HL, Li B, Xu J, Wang Y, He Y, Zheng Y, Wang XM. Tenuigenin protects dopaminergic neurons from inflammation-mediated damage induced by the lipopolysaccharide. CNS Neurosci. Ther. 2012;18:584–590. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2012.00347.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yuan Q, Wang CW, Shi J, Lin ZX. Effects of Ginkgo biloba on dementia: An overview of systematic reviews. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2017;195:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2016.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou XY, Cao J, Han CM, Li SW, Zhang C, Du YD, Zhou QQ, Zhang XY, Chen X. The C8 side chain is one of the key functional group of Garcinol for its anti-cancer effects. Bioorg. Chem. 2017;71:74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.bioorg.2017.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]