Abstract

Objective:

Cross-sectional imaging is now recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for patients with suspected and newly diagnosed myeloma instead of skeletal survey. The objectives of this study were: (1) To evaluate compliance of current UK imaging practice with reference to National Institute for Health and Care Excellence best-practice clinical guidelines for plasma cell malignancies. (2) To identify factors which may influence diagnostic imaging choices.

Methods:

We conducted a national online survey to assess compliance with guidelines and to identify challenges to implementation (endorsed by Myeloma UK, UK Myeloma Forum and the British Society of Skeletal Radiologists).

Results:

Responses were received from 31 district general and 28 teaching hospitals. For suspected and confirmed myeloma, skeletal survey remained the most frequent first-line imaging test (suspected myeloma 44.3%, confirmed myeloma 37.7%). Only 9.8 % of responders offered first-line whole body MRI.

Conclusion:

Significant challenges remain to standardisation of imaging practice in accordance with national best-practice guidelines.

Advances in knowledge:

This is the first publication to date evaluating current UK imaging practice for assessing myeloma since the publication of new guidelines recommending use of advanced cross-sectional imaging techniques. Skeletal survey remains the most commonly performed first-line imaging test in patients with suspected or confirmed myeloma and this is largely due to resource limitations within radiology departments.

Introduction

Whole body MRI (WB-MRI) or whole body CT (WB-CT) or 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography/CT (18F-FDG PET/CT) are now recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE 2016, NG 35)1 and the British Society of Haematology 2017] guidelines2 for evaluating patients with suspected and newly diagnosed myeloma and solitary plasmacytoma. Current International Myeloma Working Group guidelines include the detection of greater than one unequivocal bone lesion on MRI (>5 mm) or one or more lytic bone lesion detected on CT scan, including WB-CT or 18F-FDG PET/CT, as sufficient to fulfill the criteria for myeloma-defining bone disease.3 NICE guidelines state that WB-MRI (or WB-CT if patient declines or is unsuitable for MRI) should be considered as the first-line imaging test in patients with suspected myeloma. In patients with confirmed newly diagnosed myeloma, WB-MRI, WB-CT or 18F-FDG PET/CT should be considered to assess for myeloma-related bone disease and extramedullary plasmacytomas.1 These guidelines acknowledge research showing that skeletal survey (SS) is inferior to WB-MRI, WB-CT or 18F-FDG PET/CT in the detection of myeloma related bone disease.4 Thus SS, the former gold standard imaging test, should only be considered in suspected myeloma if WB-MRI or WB-CT is unsuitable or declined by the patient. We hypothesized that there may be significant regional variations in imaging practice despite best-practice recommendations.

Methods and Materials

We conducted an online survey of myeloma imaging practice between 01 September and 31 October 2017, endorsed by Myeloma UK, UK Myeloma Forum and the British Society of Skeletal Radiologists. This was publicised to their members via an online link. Participants comprised both clinical haematologists and radiologists with an interest in plasma cell malignancies. Participants recorded the preferred first-line imaging test for suspected myeloma, confirmed new myeloma and solitary plasmacytoma for their institution. Participants were also asked to rank the order of preference for SS, WB-CT, MRI whole spine, WB-MRI and 18F-FDG PET/CT in baseline imaging for suspected and confirmed myeloma and plasmacytoma at their institution. We sought information regarding institution type [district general hospital (DGH) or teaching hospital (TH)]. Local challenges to implementing a WB-MRI or 18F-FDG PET/CT service were also explored. The questionnaire is shown in Figure 1 .

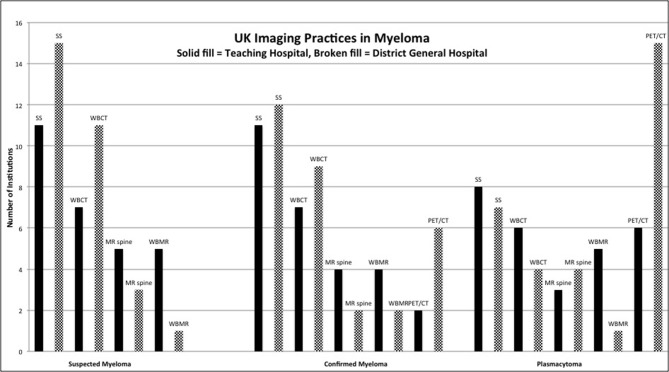

Figure 1. .

UK survey of imaging practice in myeloma. The actual survey was distributed using an online platform. 18F-FDG, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose; PET, positron emission tomography.

Results

There were 67 responses. Following removal of duplicates, there were responses from 31 DGHs, 28 THs and 2 unconfirmed sites. For suspected and confirmed myeloma, SS remained the most commonly performed first-line imaging test; suspected myeloma 44.3% (15 DGH, 11 TH); confirmed myeloma 37.7% (12 DGH, 11 TH), followed by WB-CT; suspected myeloma 29.5% (11 DGH, 7 TH); confirmed myeloma 26.2% (9 DGH, 7 TH). SS was also the preferred first-line imaging test at THs. Only 9.8% of participants reported that WB-MRI was the preferred first-line imaging test at their institution for suspected and confirmed myeloma (suspected myeloma: 5 TH, 1 DGH; confirmed myeloma: 4 TH, 2 DGH).

For plasmacytoma, 18F-FDG PET/CT was the preferred first-line imaging test overall at 36.1% (15 DGH, 6 TH) followed by SS at 26.2% (7 DGH, 8 TH). WB-MRI and WB-CT were the preferred first-line imaging tests in plasmacytoma in 9.8% (6/61) and 16.4% (10/61) of institutions respectively.

For confirmed myeloma, 18F-FDG PET/CT was the preferred first-line imaging test in 14.8% (9/61 institutions). For confirmed myeloma and plasmacytoma, a greater proportion of DGHs performed 18F-FDG PET/CT as the first-line imaging test compared with THs (confirmed myeloma 6 DGH, 2 TH, 1 unknown institution type; plasmacytoma 15 DGH, 6 THs). 18F-FDG PET/CT was not performed in suspected myeloma.

46.4% of responders offered 18F-FDG PET/CT at their institution. Where 18F-FDG PET/CT was not available, the commonest reported challenges were financial (26.8%) and scanner availability (14.3%). Only 16.4% of responders offered WB-MRI, with a slightly greater proportion of THs, and only 9.8% as a first-line imaging test. The commonest reported challenges to implementing a WB-MRI service were scanner availability (66.7%), dedicated reporting time (66.7%), financial constraints (54.0%) and availability of radiologists trained to report WB-MRI (54.0%). Results are displayed in Figure 2.

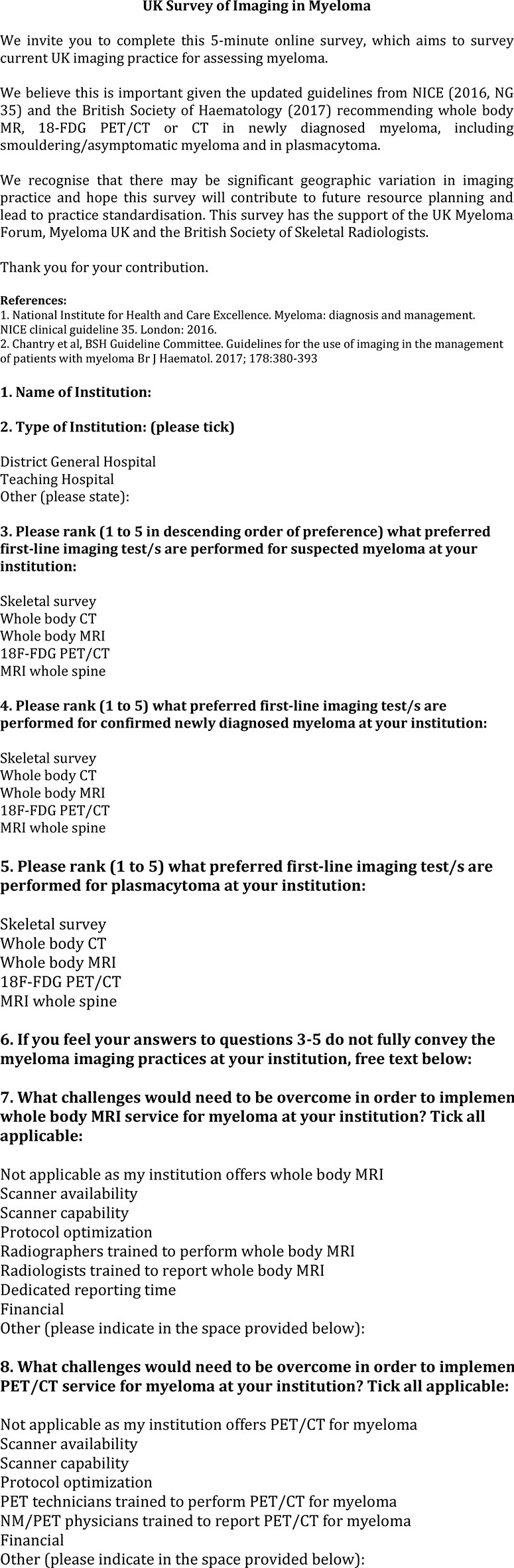

Figure 2. .

Bar chart displaying results of the UK imaging practices in myeloma survey. WB, whole body.

Discussion

WB-MRI is now recognised by NICE as the gold-standard imaging test for suspected myeloma due to its superior sensitivity in the detection of myeloma-related bone disease.5 It enables accurate documentation of pattern and extent of disease. It detects bone marrow involvement prior to cortical destruction. Studies have demonstrated that WB-MRI has a greater sensitivity and specificity for detection of focal bone lesions in myeloma compared with both WB-CT (n = 41)6 and 18F-FDG PET/CT (n = 22).7

A standard WB-MRI protocol includes a T1 weighted and diffusion-weighted sequence (or short tau inversion recovery sequence, if this is not possible) from the vertex to knees. A T1 weighted sequence following gadolinium contrast-administration improves sensitivity for bone lesion detection8 and should be considered in patients with adequate renal function. A T2 weighted sequence may augment assessment of extraosseous disease and complications of bone disease such as vertebral compression fractures and cord/cauda equina compression. A WB-MRI example is shown in Figure 3 .

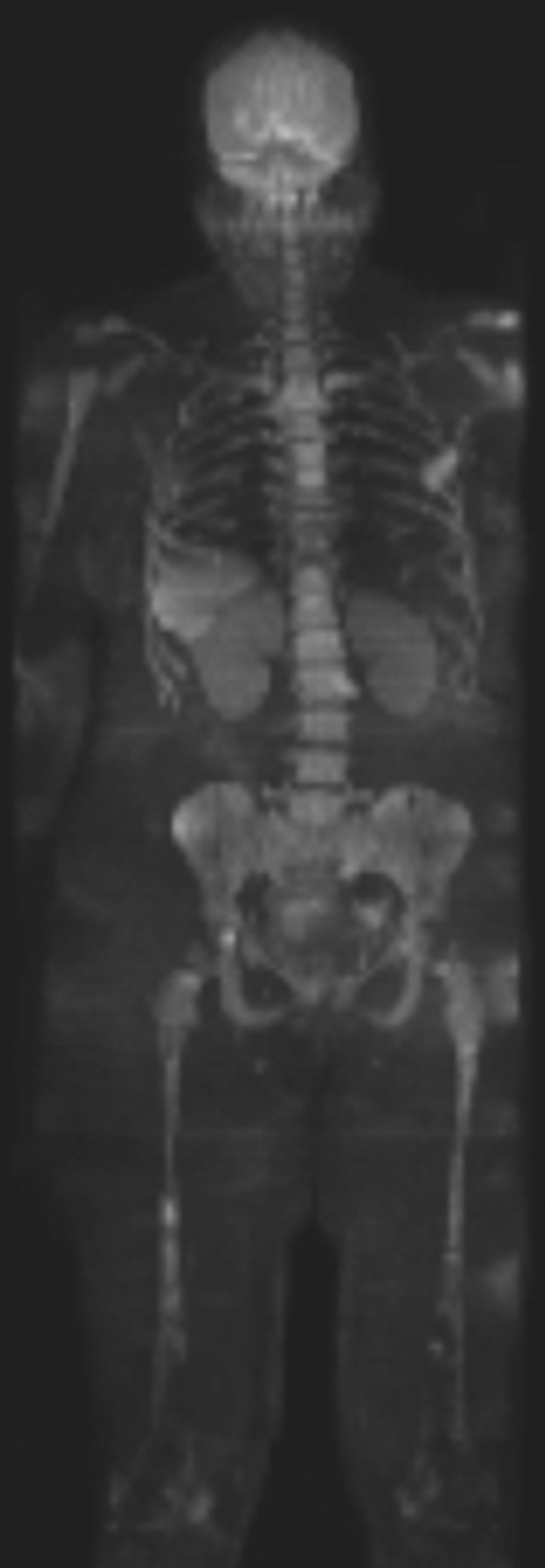

Figure 3. .

WBMR coronal MIP B900 diffusion-weighted image in a patient with newly diagnosed myeloma. There are multiple focal lesions, e.g. within the spine, pelvis and femora on a background of diffuse bone marrow infiltration. WBMR, whole body MR.

Diffusion-weighted imaging performed as part of a WB-MRI examination, depicts the free diffusion/random motion of water molecules, which differs between fatty marrow and areas with plasma cell infiltration. Thus DWI sequences are sensitive for both focal and diffuse patterns of bone marrow infiltration.9 In particular, DWI improves WB-MRI detection of rib lesions, previously challenging to assess at MRI, however sensitivity for detection of skull lesions remains inferior to SS, likely secondary to high background brain diffusion signal.10

Nevertheless, our survey found poor compliance with NICE guidance. Only 16.4% of responders offered WB-MRI and only 9.8% as the first-line imaging test in suspected or confirmed myeloma. Current rising healthcare demands and financial constraints coupled with national radiologist shortages are clear underlying contributory factors to the current imaging landscape. The three commonest stated challenges were scanner capacity, reporting time and radiologists trained to report WB-MRI.

The average duration of a WB-MRI scan is 45 minutes11 thus requiring a scheduled appointment of at least an hour. MRI scanner capacity and scanner capability will be an issue for most NHS hospitals. However with 5540 new diagnoses per year in the UK (Cancer Research UK),12 the number of newly diagnosed patients per hospital site per annum will be relatively small in comparison to other tumour types, e.g., lung (46,388 new diagnoses per year12 and colorectal cancer (41,804 new diagnoses per year,12 where WB-MRI is being considered for initial staging.13

In terms of reporting, an experienced radiologist trained in WB-MRI will take an average of 30 min to report an examination, although the reporting time will vary according to experience and the number of comparative WB-MRI examinations. There are training courses available for WB-MRI in the UK however capacity again is an issue. If NICE guidance is to be implemented successfully nationally, this will have to be addressed.

WB-CT was the second preferred first-line imaging test for suspected and confirmed myeloma in our survey. A non-contrast WB-CT is quick to perform and is well tolerated by patients. The radiation dose for a very low dose protocol approaches that of SS with new iterative reconstructions (2.5 mSv approx. SS dose for 70 kg patient).2 Additional to the detection of osteolytic lesions, WB-CT can assess vertebral fractures, spinal stability and may be used in operative planning.

Evaluation of soft tissue involvement, retropulsion and spinal canal impingement is inferior to MRI, the imaging gold standard for spinal cord assessment. Only one study to date has compared the diagnostic performance of WB-CT with WB-MRI in myeloma (n = 41), where WB-MRI detected a greater number of lesions, upstaging 11 patients.6 NICE guidelines state that WB-CT should be considered as an alternative in patients with asymptomatic myeloma and suspected myeloma where WB-MRI is not available/unsuitable. Figure 4 demonstrates a multifocal pattern of bone disease on whole body CT in a patient with relapsed myeloma.

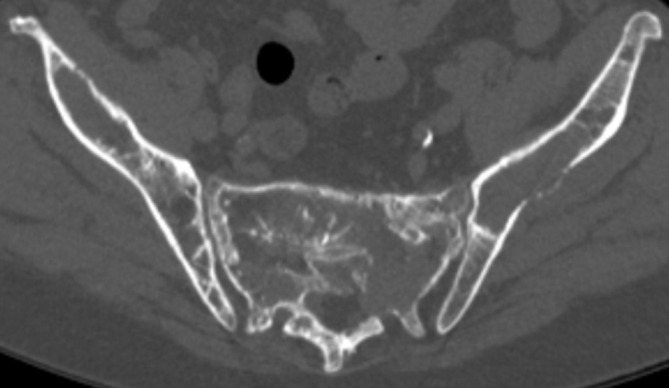

Figure 4. .

Axial WBCT image in a patient with relapsed myeloma. There are multifocal lytic lesions within the pelvis. WBCT, whole body CT.

Dual energy CT (DECT), where imaging is obtained at two distinct kilovolt peaks, improves the sensitivity of standard WB-CT for detection of bone marrow infiltration (standard WBCT = 69.6% sensitivity, virtual noncalcium technique = 91.3%, n = 34).14 Using a technique based on the principles of the virtual noniodine technique, DECT can generate an automated virtual noncalcium map, whereby trabeculated bone is subtracted from the bone marrow. Furthermore, in a recent study comparing DECT with MRI in 34 patients with MGUS or myeloma, Kosmala et al by using tin filtration, were able to separate yellow marrow from nonfat-containing soft tissue, thus highlighting potential regions of bone marrow replacement.14 Important considerations affecting adoption of this technique include availability of DECT scanners, variations in scanner type, physicist support and radiation dose (mean volume CT dose index for WB-DECT = 9.7 ± 4.3 mGy).14 Further studies are required comparing the sensitivity and specificity of WB-CT ± DECT component compared with WB-MRI in detection of bone disease in myeloma.

The sensitivity of 18F-FDG PET/CT for detection of focal bone lesions is similar to WB-MRI, however, WB-MRI is more sensitive in the detection of diffuse and variegated disease patterns.15 In response assessment/ detection of relapse, 18F-FDG PET/CT has a clear role, distinguishing between active and inactive myeloma (meta-analysis, n = 690.16 18F-FDG PET/CT has also been shown to have prognostic value in myeloma. In a study by Zagmani et al,17 both progression-free and overall survival were adversely affected by the presence of extramedullary disease, three or more focal lesions at baseline and a maximum standardized uptake value greater than 4.2. An additional benefit of 18F-FDG is that is safe to use in patients with renal impairment. The choice of 18F FDG PET/CT in this survey likely reflects easier access to centralised PET services for DGHs.

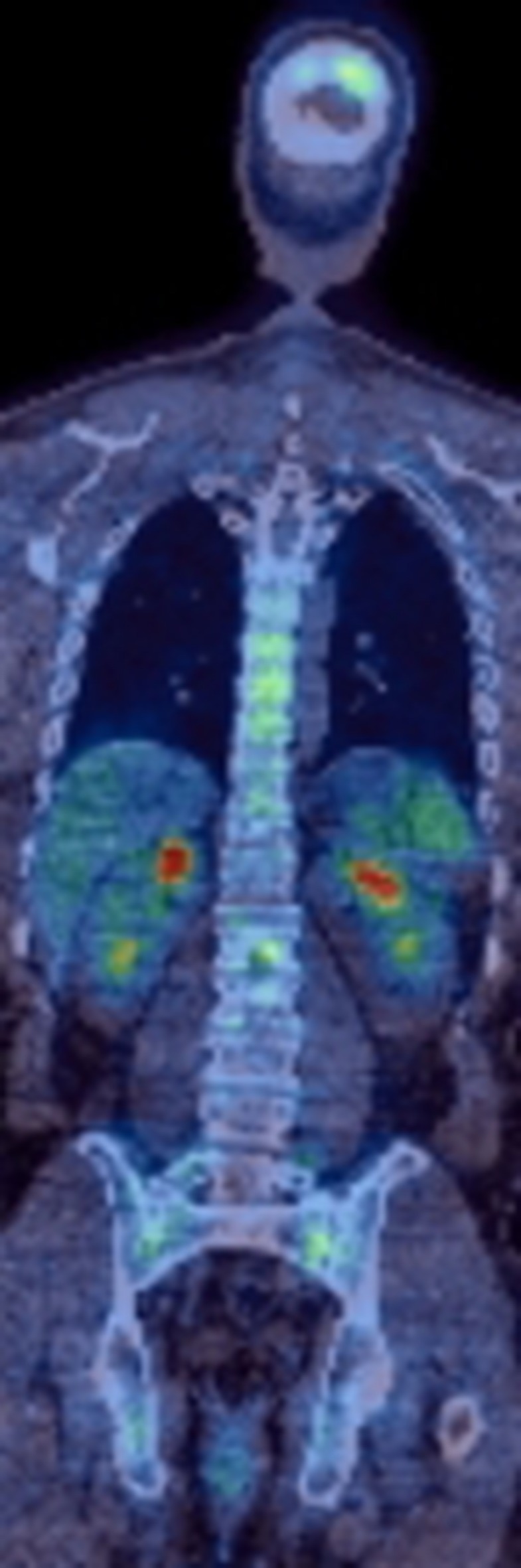

18F-FDG is currently the only recommended radiopharmaceutical for clinical imaging in myeloma; however, it is recognised that approximately 11% of patients with myeloma do not have FDG avid disease.18 Suggested underlying mechanisms for this include reduced expression of the enzyme hexokinase-2, involved in the first step of glucose metabolism18 and low volume plasma cell infiltration.19 Alternative tracers such as choline may have improved sensitivity for detection of focal bone lesions in myeloma.20 Choline is a cell membrane phospholipid precursor and therefore, a marker of cell membrane turnover.21 It is possible that increased choline utilization may precede increased glucose utilization in malignant plasma cells. Further research regarding the optimal radiopharmaceutical in myeloma imaging is needed. Figure 5 is a representative 18F-FDG PET/CT image in a patient with multifocal pattern of myeloma.

Figure 5. .

18F-FDG PET/CT coronal image in a patient with newly diagnosed myeloma. There is multifocal FDG-avid skeletal disease. 18F-FDG, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose.

Another issue not captured in our survey is that a significant minority of patients with suspected myeloma have SS and then subsequently an advanced imaging technique. This pathway often makes the initial SS unnecessary and is the least cost-effective or patient-centered pathway. In view of this, being current practice for a minority of patients, NICE felt that screening with WB-CT or WB-MRI alone (with no use of SS) in myeloma could be cost effective as long as screening was restricted to a population where myeloma was likely, i.e. not patients with straightforward MGUS.1

A limitation of this survey is that it only provides a snapshot of national imaging practices in myeloma and there may be local variations in practice that are not captured by our results. In the authors’ experience, the results are thought to be broadly representative of current practice in this field.

Conclusion

Whilst recent guidelines recommend that advanced imaging techniques should replace SS, there is poor compliance nationally. Significant challenges remain to the standardisation of UK imaging practice. Substantial investment in radiology services including equipment, increased scanning capacity, staffing and training will be required in order to ensure all patients in the UK have the opportunity to benefit from advanced imaging techniques in the initial assessment of plasma cell malignancy.

Footnotes

Acknowledgements: With grateful acknowledgement of Myeloma UK, UK Myeloma Forum and the British Society of Skeletal Radiologists for their input to and support in implementing this survey. The authors also acknowledge support from the Department of Health via the National Institute for Health Research Comprehensive Biomedical Research Centre award to Guy’s & St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust in partnership with King’s College London and King's College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust; from the King’s College London/University College London Comprehensive Cancer Imaging Centre funded by Cancer Research UK and Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC) in association with the Medical Research Council and Department of Health ((C1519/A16463)); and Wellcome EPSRC Centre for Medical Engineering at King’s College London (WT 203148/Z/16/Z).

Contributor Information

Olwen Amy Westerland, Email: olwen.westerland@gstt.nhs.uk.

Guy Pratt, Email: Guy.Pratt@uhb.nhs.uk.

Majid Kazmi, Email: majid.kazmi@gstt.nhs.uk.

Inas El-Najjar, Email: inas.el-najjar@gstt.nhs.uk.

Matthew Streetly, Email: matthew.streetly@gstt.nhs.uk.

Kwee Yong, Email: kwee.yong@ucl.ac.uk.

Monica Morris, Email: mmorris@arci.org.uk.

Rakesh Mehan, Email: Rakesh.Mehan@boltonft.nhs.uk.

Martin Sambrook, Email: m.sambrook@nhs.net.

Margaret Hall-Craggs, Email: margaret.hall-craggs@nhs.net.

David Silver, Email: davidsilver@nhs.net.

Vicky Goh, Email: vicky.goh@kcl.ac.uk.

REFERENCES

- 1.NICE guideline [NG35] Myeloma: diagnosis and management. 2016 February 2016.

- 2.Chantry A, Kazmi M, Barrington S, Goh V, Mulholland N, Streetly M, et al. Guidelines for the use of imaging in the management of patients with myeloma. Br J Haematol 2017; 178: 380–93. doi: 10.1111/bjh.14827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Palumbo A, Blade J, Merlini G, Mateos MV, et al. International Myeloma Working Group updated criteria for the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol 2014; 15: e538–e548. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(14)70442-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Regelink JC, Minnema MC, Terpos E, Kamphuis MH, Raijmakers PG, Pieters-van den Bos IC, et al. Comparison of modern and conventional imaging techniques in establishing multiple myeloma-related bone disease: a systematic review. Br J Haematol 2013; 162: 50–61. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dimopoulos MA, Hillengass J, Usmani S, Zamagni E, Lentzsch S, Davies FE, et al. Role of magnetic resonance imaging in the management of patients with multiple myeloma: a consensus statement. J Clin Oncol 2015; 33: 657–64. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.57.9961 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baur-Melnyk A, Buhmann S, Becker C, Schoenberg SO, Lang N, Bartl R, et al. Whole-body MRI versus whole-body MDCT for staging of multiple myeloma. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2008; 190: 1097–104. doi: 10.2214/AJR.07.2635 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cascini GL, Falcone C, Console D, Restuccia A, Rossi M, Parlati A, et al. Whole-body MRI and PET/CT in multiple myeloma patients during staging and after treatment: personal experience in a longitudinal study. Radiol Med 2013; 118: 930–48. doi: 10.1007/s11547-013-0946-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dutoit JC, Vanderkerken MA, Verstraete KL. Value of whole body MRI and dynamic contrast enhanced MRI in the diagnosis, follow-up and evaluation of disease activity and extent in multiple myeloma. Eur J Radiol 2013; 82: 1444–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2013.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dutoit JC, Vanderkerken MA, Anthonissen J, Dochy F, Verstraete KL. The diagnostic value of SE MRI and DWI of the spine in patients with monoclonal gammopathy of undetermined significance, smouldering myeloma and multiple myeloma. Eur Radiol 2014; 24: 2754–65. doi: 10.1007/s00330-014-3324-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Narquin S, Ingrand P, Azais I, Delwail V, Vialle R, Boucecbi S, et al. Comparison of whole-body diffusion MRI and conventional radiological assessment in the staging of myeloma. Diagn Interv Imaging 2013; 94: 629–36. doi: 10.1016/j.diii.2013.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Messiou C, Kaiser M. Whole body diffusion weighted MRI-a new view of myeloma. Br J Haematol 2015; 171: 29–37. doi: 10.1111/bjh.13509 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cancer Research UK. Myeloma statistics. 2015. Available from: http://www.cancerresearchuk.org/cancerinfo/cancerstats/types/myeloma/uk-multiple-myeloma-statistics.

- 13.Taylor SA, Mallett S, Miles A, Beare S, Bhatnagar G, Bridgewater J, et al. Streamlining staging of lung and colorectal cancer with whole body MRI; study protocols for two multicentre, non-randomised, single-arm, prospective diagnostic accuracy studies (Streamline C and Streamline L. BMC Cancer 2017; 17: 299. doi: 10.1186/s12885-017-3281-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kosmala A, Weng AM, Heidemeier A, Krauss B, Knop S, Bley TA, et al. Multiple myeloma and dual-energy CT: diagnostic accuracy of virtual noncalcium technique for detection of bone marrow infiltration of the spine and pelvis. Radiology 2018; 286: 205–13. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2017170281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Breyer RJ. 3rd, Mulligan, M.E., Smith, S.E., Line, B.R. & Badros, A.Z. Comparison of imaging with FDG PET/CT with other imaging modalities in myeloma. Skeletal Radiology 2006; 35: 632–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caldarella C, Treglia G, Isgrò MA, Treglia I, Giordano A. The role of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography in evaluating the response to treatment in patients with multiple myeloma. Int J Mol Imaging 2012; 2012: 1–6. doi: 10.1155/2012/175803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zamagni E, Patriarca F, Nanni C, Zannetti B, Englaro E, Pezzi A, et al. Prognostic relevance of 18-F FDG PET/CT in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma patients treated with up-front autologous transplantation. Blood 2011; 118: 5989–95. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-06-361386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rasche L, Angtuaco E, McDonald JE, Buros A, Stein C, Pawlyn C, et al. Low expression of hexokinase-2 is associated with false-negative FDG-positron emission tomography in multiple myeloma. Blood 2017; 130: 30–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-03-774422 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mesguich C, Zanotti-Fregonara P, Hindié E. New perspectives offered by nuclear medicine for the imaging and Therapy of multiple Myeloma. Theranostics 2016; 6: 287–90. doi: 10.7150/thno.14400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nanni C, Zamagni E, Cavo M, Rubello D, Tacchetti P, Pettinato C, et al. 11C-choline vs. 18F-FDG PET/CT in assessing bone involvement in patients with multiple myeloma. World J Surg Oncol 2007; 5: 68. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-5-68 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vij R, Fowler KJ, Shokeen M. New Approaches to Molecular Imaging of Multiple Myeloma. J Nucl Med 2016; 57: 1–4. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.115.163808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]