Abstract

Background:

This randomized controlled trial evaluated the effectiveness of nerve electrical stimulation (NES) for the treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) in patients with advanced gastric cancer (AGC).

Methods:

One hundred twenty-four eligible patients with AGC were included in this randomized controlled trial. They were equally divided the NES group and the sham group. The patients in the NES group received NES intervention, while the subjects in the sham group underwent sham NES. The primary outcome included symptoms severity and appetite. The secondary outcomes included quality of life, as measured by the MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) score, and functional impairment, as evaluated by the Karnofsky score. Additionally, adverse events were also documented during the period of the treatment.

Results:

After treatment, NES showed greater effectiveness in reducing the severity of nausea (P = .02), and vomiting (P = .04), as well as the appetite improvement (P = .02), compared with the sham NES. Furthermore, no adverse events related to NES treatment were detected.

Conclusion:

The results of this study demonstrated that NES may help to relieve CINV in patients with AGC. Future studies are still needed to warrant these results.

Keywords: advanced gastric cancer, adverse event, chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, effectiveness, nerve electrical stimulation

1. Introduction

Gastric cancer (GC) is the second leading cause of cancer deaths.[1,2] It is also the fourth most common cancer worldwide.[3,4] It has been reported that it accounts for 997,000 new diagnoses and 738,000 deaths each year.[5,6] In China alone, it is reported that more than 300,000 new cases and 200,000 cases death are associated with GC annually.[7] In addition, it also ranks as the third most common cancers among Chinese population.[8] This condition is often hard to cure because it is difficult to be detected until the advanced stage.[6] For advanced gastric cancer (AGC), chemotherapy has demonstrated a survival benefit for patients with AGC.[9–11]

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting (CINV) is one of the most common side-effects in patients with cancer.[12–14] It not only significantly affects the quality of life and nutritional status for patients with AGC, but also may result in dose decrease or even the treatment discontinuation, and then worsen the disease progression.[15]

The management for CINV is recommended by using emetogenic chemotherapies, according to the clinical guidelines.[16,17] However, such therapies are too expensive and also companied lots of side effects, including insomnia, headaches, dizziness, and constipation.[18]

Alternative therapies are also one of the most potential modalities for treating CINV in patients with cancer. It is not only a safe medical procedure but also has minimal side effects, when compared with the medications. These interventions include acupuncture, electroacupuncture, and nerve electrical stimulation (NES).[19–22] However, no data on the effectiveness of NES for treating CINV in patients with AGC are available among Chinese population. Therefore, this study specifically assessed the efficacy of NES for the treatment of CINV in Chinese patients with AGC.

2. Patients and methods

2.1. Ethics

This study was approved by the ethics medical committee of Yulin No.2 Hospital, and investigations were operated based on the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials Statement. All patients signed the written informed consent.

2.2. Study design

This study is a randomized, sham-controlled trial and it aimed to explore the efficacy and safety of NES for the treatment of CINV in patients with AGC. A total of 124 eligible patients were included in this study and were randomly allocated into the NES group or the sham group in a 1:1 ratio.

2.3. Patients

This study was conducted at Yulin No.2 Hospital from May 2016 to April 2018. All included patients were aged from 18 to 75 years old, and they must meet all the inclusion criteria. They were all confirmed diagnosed with AGC.[23,24] All of them received chemotherapy. All patients were instructed the research explanation and were informed about the study design. However, the patients were excluded if they underwent NES, acupuncture, or electroacupuncture 2 months before the study. They were also excluded if they were pregnancy, breastfeeding, unconsciousness, installing pacemaker, cognitive dysfunction or did not like to participant the study or could not tolerate the stimulation of NES.

2.4. Randomization and blinding

A total of 124 patients were equally randomly allocated into the NES group or the sham group, with 62 subjects in each group. The block randomization procedure was applied in a 1:1 ratio according to the generated sequence by using 9.1.0 SAS software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). The allocation information was sealed in opaque envelopes. The investigators, patients, outcome assessors, and data analysts were masked to the procedure of randomization and allocation.

2.5. Treatment schedule

All patients in both groups were treated at bilateral acupoints Neiguan (P6, located 3 finger breadths below the wrist on the inner forearm in between the 2 tendons), Zusanli (ST36, located below the knee, on the tibialis anterior muscle, along the stomach meridian), and Hegu (LI4, located on the dorsum of the hand, between the first and second metacarpal bones, approximately in the middle of the second metacarpal bone on the radial side) for 30 minutes daily, 7 times weekly for a total of 1 week. The P6 and LI4 were connected at the same side as a pair of acupoints, while the bilateral ST36 were connected as a pair of acupoints. In the NES group, The NES device (HANS-100, Nanjing Jisheng Medical Technology Co., Ltd) was applied at a frequency of 2 to 100 Hz, within an intensity of each individual's maximum tolerance. Each NES device had 2 gel pads attached to a silicon patch, which was attached to the selected acupoints area in this study. In the sham group, the gel pads were placed on the same acupoints and treated for the same treatment period as the NES group, except no electric stimulation was applied.

2.6. Outcome measurements

The primary outcomes consisted of severity of symptoms and appetite. The severity of nausea and vomiting were measured by the diary records of nausea and vomiting.

The appetite was measured by Anorexia scale using visual analog score (VAS), ranging from 0, normal appetite, to 10, no appetite at all, with higher score indicating worse appetite.[25]

The secondary outcome included The MD Anderson Symptom Inventory (MDASI) score was applied to evaluate the quality of life, the higher score indicating the poorer quality of life.[26] Moreover, Karnofsky score was utilized to measure the functional impairment, the higher the score, the better survival for the serious illness.[27] In addition, adverse events were also recorded during the treatment period.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All characteristic and outcome values were analyzed by the 9.1.0 SAS software. The intention-to-treat principle was utilized to analyze the outcome data in this study. The t test or Wilcoxon test was used to analyze the continuous data. The Pearson chi-square test or Fisher exact test was performed to analyze the categorical data. A value of P <.05 was defined as having statistical significance.

3. Results

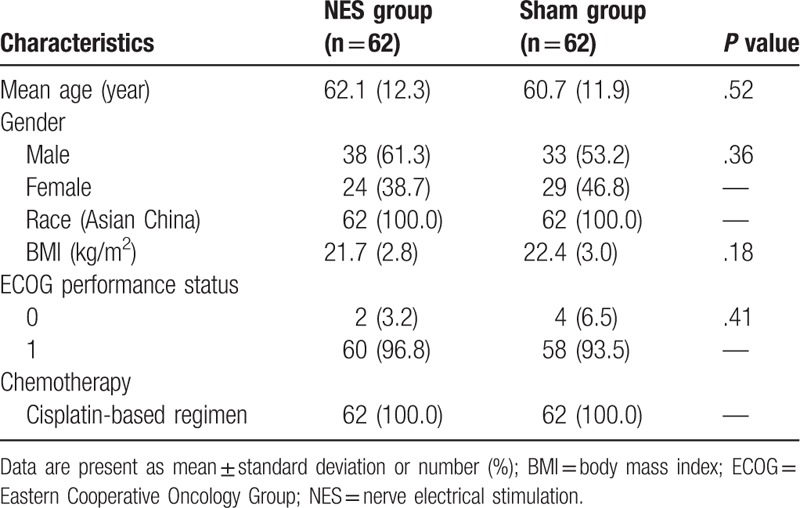

In total, 195 patients entered the study (Fig. 1). Of these, 71 subjects were excluded because they did not meet inclusion criteria (n = 39), met exclusion criteria (n = 23), and did not agree to participate (n = 9). Thus, the remaining 124 participants were randomly divided into the NES group (n = 62) and sham group (n = 62). Three patients withdrew from the study, because of the consent withdrawal (Fig. 1). The final analysis included all 124 subjects in this study. The baseline characteristic values are listed in Table 1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patient selection.

Table 1.

Comparison of patient characteristics at baseline.

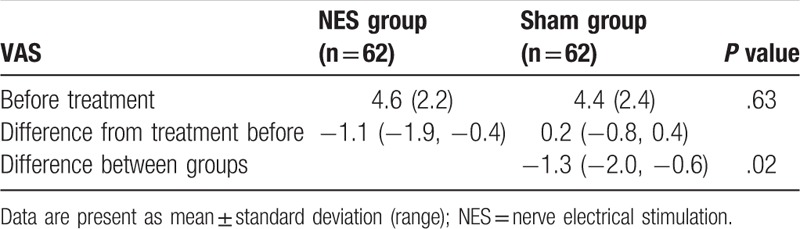

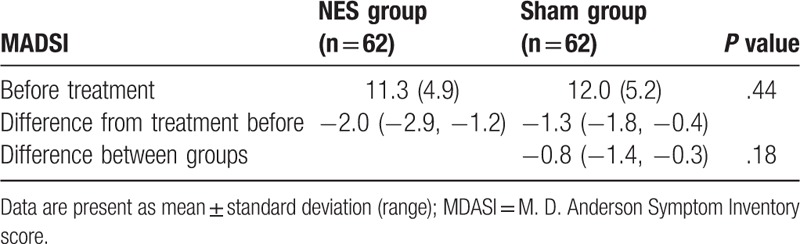

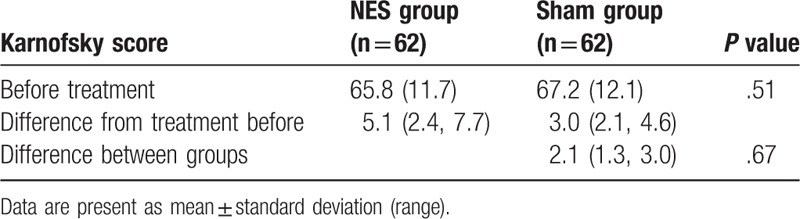

After treatment, patients in the NES group did show much better outcomes in the severity reduction of nausea (P = .02, Table 2) and vomiting (P = .04, Table 2), and in the improvement of appetite (P = .02, Table 3), compared with subjects in the sham group. However, there were not significant differences in quality of life, measure by MDASI (P = .18, Table 4), and functional impairment (P = .67, Table 5) between 2 groups.

Table 2.

Comparison the severity of nausea and vomiting between 2 groups.

Table 3.

Comparison of Anorexia VAS before and after treatment between 2 groups.

Table 4.

Comparison of quality of life before and after treatment between 2 groups.

Table 5.

Comparison of functional impairment before and after treatment between 2 groups.

Regarding the adverse events, no significant differences of all adverse events were detected between 2 groups (Table 6). Although several adverse events were documented, they all result from the chemotherapies, not from the intervention of NES.

Table 6.

Comparison of adverse events between 2 groups.

4. Discussion

This randomized controlled trial showed promising outcomes after NES treatment for CINV in patients with AGC. To our best knowledge, no data are available specifically regarding the NES therapy for treating ASC patients with CINV. In this study, we first explored the efficacy of NES intervention for the treatment of CINV in patients with AGC.

Although one previous related study investigated the clinical effectiveness of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation (TEAS) on CINV, all the included patients were liver cancer, but not the stomach cancer.[20] In addition, this study utilized acupuncture therapy to treat such this condition, not the NES. The results found that TEAS is efficacious and safety to relieve nausea and vomiting after chemotherapy.[20]

In this study, our results demonstrated that NES is safe and efficacious for CINV in patients with AGC after treatment. The results showed that NES could not only decrease the severity of nausea and vomiting but also could enhance the appetite for patients with AGC when compared with the sham NES, although negative results were found in the quality of life improvement, as well as the functional impairment between 2 groups. In addition, no NES treatment-related adverse events were detected. The results indicated that NES may help to relieve the CINV in AGC patients.

This study has 2 limitations. First, this study was only conducted in one center of Yulin No.2 Hospital, which may affect the generalization of its results to the centers. Second, this study just assessed the short-term efficacy and safety of NES for CINV in AGC patients, because it did not consist of follow-up evaluation for all outcomes. Thus, further studies should focus to explore its longer efficacy and safety. Future studies should avoid the above limitations.

5. Conclusion

The results of this study demonstrated that NES may be efficacious and safety for CINV in patients with AGC. Further studies are still needed to warrant these results.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: Fang Wang, Wen-cheng Guo.

Data curation: Fang Wang, Wen-cheng Guo.

Formal analysis: Wen-cheng Guo.

Investigation: Fang Wang.

Methodology: Wen-cheng Guo.

Project administration: Fang Wang.

Resources: Fang Wang, Wen-cheng Guo.

Software: Wen-cheng Guo.

Supervision: Fang Wang.

Validation: Wen-cheng Guo.

Visualization: Fang Wang, Wen-cheng Guo.

Writing – original draft: Fang Wang, Wen-cheng Guo.

Writing – review & editing: Fang Wang, Wen-cheng Guo.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: AGC = advanced gastric cancer, CINV = chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting, GC = gastric cancer, MDASI = MD Anderson Symptom Inventory, NES = nerve electrical stimulation, TEAS = transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

References

- [1].Torre LA, Bray F, Siegel RL, et al. Global cancer statistics, 2012. CA Cancer J Clin 2015;65:87–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Jemal A, Bray F, Center MM, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin 2011;61:69–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Sitarz R, Skierucha M, Mielko J, et al. Gastric cancer: epidemiology, prevention, classification, and treatment. Cancer Manag Res 2018;10:239–48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Patru CL, Surlin V, Georgescu I, et al. Current issues in gastric cancer epidemiology. Rev Med Chir Soc Med Nat Iasi 2013;117:199–204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Wagner AD, Moehler M. Development of targeted therapies in advanced gastric cancer: promising exploratory steps in a new era. Curr Opin Oncol 2009;21:381–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Forman D, Burley VJ. Gastric cancer: global pattern of the disease and an overview of environmental risk factors. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol 2006;20:633–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Sun DZ, Jiao JP, Ju DW, et al. Tumor interstitial fluid and gastric cancer metastasis: an experimental study to verify the hypothesis of “tumor-phlegm micro-environment”. Chin J Integr Med 2012;18:350–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Park JW, Yoon J, Cho CK, et al. Survival analysis of stage IV metastatic gastric cancer patients treated with HangAm-Plus. Chin J Integr Med 2014;20:49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Wagner AD, Syn NL, Moehler M, et al. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2017;8:CD004064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Min YJ, Bang SJ, Shin JW, et al. Combination chemotherapy with 5-fluorouracil and heptaplatin as first-line treatment in patients with advanced gastric cancer. J Korean Med Sci 2004;19:369–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Takiuchi H. Chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer: a new milestone lies ahead. Gastrointest Cancer Res 2007;1:209–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Adel N. Overview of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and evidence-based therapies. Am J Manag Care 2017;23suppl 14:S259–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Singh KP, Dhruva AA, Flowers E, et al. A review of the literature on the relationships between genetic polymorphisms and chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 2018;121:51–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Storz E, Gschwend JE, Retz M. Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: current recommendations for prophylaxis. Urologe A 2018;57:532–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Bloechl-Daum B, Deuson RR, Mavros P, et al. Delayed nausea and vomiting continue to reduce patients’ quality of life after highly and moderately emetogenic chemotherapy despite antiemetic treatment. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:4472–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Rapoport BL, Jordan K, Boice JA, et al. Aprepitant for the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting associated with a broad range of moderately emetogenic chemotherapies and tumor types: a randomized, double-blind study. Support Care Cancer 2010;18:423–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Aridome K, Mori SI, Baba K, et al. A phase II, randomized study of aprepitant in the prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting associated with moderately emetogenic chemotherapies in colorectal cancer patients. Mol Clin Oncol 2016;4:393–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Schwartzberg LS, Modiano MR, Rapoport BL, et al. Safety and efficacy of rolapitant for prevention of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting after administration of moderately emetogenic chemotherapy or anthracycline and cyclophosphamide regimens in patients with cancer: a randomised, active-controlled, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2015;16:1071–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Li QW, Yu WW, Yang GW, et al. Effect of acupuncture in prevention and treatment of chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting in patients with advanced cancer: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017;18:185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Xie J, Chen LH, Ning ZY, et al. Effect of transcutaneous electrical acupoint stimulation combined with palonosetron on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: a single-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Chin J Cancer 2017;36:6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Chen B, Hu SX, Liu BH, et al. Efficacy and safety of electroacupuncture with different acupoints for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2015;16:212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Chen B, Guo Y, Zhao X, et al. Efficacy differences of electroacupuncture with single acupoint or matching acupoints for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2017;18:477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Nagao F, Takahashi N. Diagnosis of advanced gastric cancer. World J Surg 1979;3:693–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Nakamatsu D, Nishida T, Inoue T, et al. Advanced gastric cancer deriving from submucosal heterotopic gastric glands based on pathological diagnosis. Nihon Shokakibyo Gakkai Zasshi 2013;110:290–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Stubbs RJ, Hughes DA, Johnstone AM, et al. The use of visual analogue scales to assess motivation to eat in human subjects: a review of their reliability and validity with an evaluation of new hand-held computerized systems for temporal tracking of appetite ratings. Br J Nutr 2000;84:405–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Cleeland CS, Mendoza TR, Wang XS, et al. Assessing symptom distress in cancer patients: the M.D. Anderson Symptom Inventory. Cancer 2000;89:1634–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Faul C, Gerszten K, Edwards R, et al. A phase I/II study of hypofractionated whole abdominal radiation therapy in patients with chemoresistant ovarian carcinoma: Karnofsky score determines treatment outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2000;47:749–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]