Abstract

Purpose:

p21-activated kinase 4 (PAK4) plays a significant biological and functional role in a number of malignancies, including multiple myeloma (MM). Based on our promising findings in MM, we here characterize PAK4 expression and role in WM cells, as well effect of dual PAK4-NAMPT inhibitor (KPT-9274) against WM cell growth and viability.

Experimental Design:

We have analyzed mRNA and protein expression levels of PAK4 in WM cells, and used loss-of-function approach to investigate its contribution to WM cell viability. We have further tested the in vitro and in vivo effect of KPT-9274 against WM cell growth and viability.

Results:

We report here high-level expression and functional role of PAK4 in WM, as demonstrated by shRNA-mediated knockdown; and significant impact of KPT-9274 on WM cell growth and viability. The growth inhibitory effect of KPT-9274 was associated with decreased PAK4 expression and NAMPT activity, as well as induction of apoptosis. Interestingly, in WM cell lines treated with KPT-9274, we detected a significant impact on DNA damage and repair genes. Moreover, we observed that apart from inducing DNA damage, KPT-9274 specifically decreased RAD51 and the double strand break repair by the homologous recombination pathway. As a result, when combined with a DNA alkylating agents bendamustine and melphalan, KPT-9274 provided a synergistic inhibition of cell viability in WM cell lines and primary patient WM cells in vitro and in vivo.

Conclusions:

These results support the clinical investigation of KPT-9274 in combination with DNA-damaging agent for treatment of WM.

Introduction

Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM) is characterized by lymphoplasmacytic cell infiltration of bone marrow (BM) and secretion of a serum monoclonal immunoglobulin M (IgM) protein. Recent genomic studies have contributed to a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms supporting WM pathogenesis and progression (1–3). These findings have been rapidly translated from laboratory to clinical setting, with the identification of novel therapeutic approaches and the initiation of several clinical trials for the treatment of patients with relapsed/refractory WM (4,5). However, despite this substantial progress in treating WM patients, only a few patients achieve complete remission while others develop drug-resistance. Therefore, there is a need for identifying novel targets as well as for innovative therapeutic regimens to effectively treat WM patients.

p21-activated kinase 4 (PAK4) is a member of PAK family of serine/threonine kinases with a role in cytoskeleton reorganization, cell proliferation and survival, and drug resistance(6–8). We have recently reported the oncogenic potential of PAK4 in multiple myeloma (MM) cells and provided evidence of the significant impact of the PAK4 inhibitor KPT-9274 on MM cell growth and viability, representing a potential novel therapeutic intervention in this malignancy(9). KPT-9274 is an orally administered small molecule, currently in clinical trial for the treatment of patients with advanced solid malignancies or non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NCT02702492). It allosterically binds to, destabilizes and causes the degradation of PAK4. In addition to which, we have also reported that KPT-9274 depletes the synthesis of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) by blocking the activity of nicotinamide phosphoribosyl transferase (NAMPT), the rate-limiting enzyme in the NAD biosynthesis salvage pathway.

NAD is an essential metabolite required for sustaining energy production (TCA cycle) and regulating various cellular processes. Cancer cells are characterized by higher NAD+ turnover than normal cells due to the increased energy required for their cell proliferation and metabolism, as well as regulation of transcription, chromatin dynamics, and DNA repair-processes(10). As NAD+ is rapidly consumed and converted to nicotinamide, NAMPT plays a crucial role in replenishing the intracellular NAD+ pool. Aberrant activation of NAMPT has been reported in a number of solid and hematologic malignancies, including leukemia, multiple myeloma and importantly WM(11,12).

Here, for the first time we describe a role for PAK4 in WM cell viability and report a significant impact of dual PAK4-NAMPT inhibition via KPT-9274 on WM cell growth and survival. At the molecular level, we identified the DNA damage and repair pathway to be significantly impacted by KPT-9274 leading to synergistic activity in combination with DNA-damaging agents in vitro and in vivo.

Materials and methods

Cells and Reagents.

The WM cell lines (BCWM-1, MWCL-1, RPCIWM-1) were cultured in RPMI containing 10% fetal bovin serum (GIBCO, 10437028), 2 mmol/L L-glutamine, 100 U/mL penicillin, and 100 mg/mL streptomycin (GIBCO, 15140122). Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) were isolated using Ficoll-Hypaque density gradient sedimentation. Bone marrow stromal (BMSC) cells were isolated from bone marrow aspirate of WM patients and were cultured as previously described(13). Primary WM cells were separated from BM samples by antibody-mediated positive selection using anti-CD19+ magnetic-activated cell separation microbeads (Miltenyi Biotech, 130–050-301). A purity of 95% CD19+ cells was obtained. KPT-9274 was provided by Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc.; melphalan and bendamustine were purchased from Selleckchem (Selleck Chemicals, S1212).

Cell viability and apoptosis assay.

Cell viability was analyzed by CellTiter-Glo (CTG) (Promega, G7572). Apoptosis was evaluated by flow cytometric analysis following FITC Annexin-V (BD Biosciences, 556419), PE- Annexin-V (Biolegend, 640947), DAPI (BD Biosciences, 564907) and PI (BD Biosciences, 51–6621E) staining, according to manufactor’s instructions. Caspase activities were evaluated by specific Caspase-Glo assays (Promega).

NAMPT activity.

NAMPT activity was analyzed by NAD/NADH Assay Kit (Colorimetric) (Abcam, ab65348) according to manufactor’s instructions.

Immunohistochemistry.

Normal and tumor tissue specimen sections of formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded BM biopsies were prepared and processed for immunohistochemistry to detect PAK4 and p-PAK4 (Ser474) protein expression by using specific antibodies (LifeSpan BioSciences, lsc-287254, and Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc135774).

Immunoblotting.

Western blotting (WB) was performed to evaluate the expression levels of total protein and phospho-specific isoforms using following antibodies: PAK4 (LifeSpan BioSciences, lsc-287254); FANCD2 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-20022), RAD51 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-398587), RAD51C (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc-56214), p-PAK4 (Ser 474) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc135774); NAMPT (Cell Signal, 86634), total and cleaved form of Caspase3 (Cell Signal, 9662), Caspase7 (Cell Signal, 9692), Caspase8 (Cell Signal, 9746), Caspase9 (Cell Signal, 9502s), PARP(Cell Signal, 9542s), Bcl-xl (Cell Signal, 2764s), BIM (Cell Signal, 2819), γ-H2AX (Ser139) (Cell Signal, 9718s), p-CHK1 (Ser 345) (Cell Signal, 2341), p-BAD (Ser112) (Cell Signal, 5284s), p-P53(Ser15) (Cell Signal, 9284s). Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrgenase (GAPDH) (Cell Signal, 2118), Histone3 (Cell Signal, 4499), Vinculin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc25336), and α-Tubulin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, sc8035) were used as loading control.

PAK4 knockdown.

Human GIPZ PAK4 shRNA vectors were purchased from Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO, USA). Scramble: non-silencing Lentiviral shRNA control (Catalog #RHS4346), shRNA: 396# V3LHS_646396, 682# V2LHS_197682, 934# V3LHS_643934, 937# V3LHS_643937.

RT2 Profiler PCR Array.

Human DNA Damage Signaling Pathway RT2 Profiler™ PCR Array (PAHS-029Z, Qiagen, Waltham, MA) was used to evaluate the impact of KPT-9274 on mRNA levels of 84 related genes. Relative expression was calculated using the comparative δ,δ(Ct) method, using untreated cells as control. Fold-Change (2^(- δ,δ CT)) is the normalized gene expression (2^(- δ CT)) in the treated cells divided the normalized gene expression (2^(- δ CT)) in the Control cells. Fold-change values greater than one indicate a positive- or an up-regulation; fold-change values less than one indicate a negative or down-regulation.

HR activity.

In vitro HR assay was carried out using FRET-based DNA strand exchange assay (Huang et al 2011). Briefly the BCWM1 cells were treated with different combination of drugs after 24 hours cells were harvested and lysed in chaps buffer. Cell lysate (20,000 cells) was incubated for 45 min with homologous ssDNA (Oligo 25; 48-mer) (denoted as “Homologous DNA”) to form the nucleoprotein filament. Then, fluorescently labeled dsDNA (Oligo 25-FLU and 26-BHQ1) was added to the filament to initiate DNA strand exchange. After 30 min of incubation fluorescence intensity was measured.

Murine xenograft model of human WM.

CB17-SCID mice were purchased from Charles River Laboratories. All animal studies were conducted according to protocols approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. Mice were irradiated (200 cGy) and then inoculated subcutaneously in the right flank with 10 × 106 BCMW-1 cells in 100 μL RPMI 1640. Following detection of tumor (∼3 weeks after the injection), mice were treated intraperitoneally with: KPT-9274 (100 mg/kg body weight) daily for 5 consecutive days/week for 3 weeks; or bendamustine (25 mg/kg) 1 single dose/week for 2 consecutive weeks; or the combination with the same dosing regimen used for the individual agents. The control group received the vehicle at the same schedule as the combination group. Tumor volume was evaluated in 2 dimensions by caliper measurements performed approximately twice a week using the following formula: V = 0.5a × b2, where “a” and “b” are the long and short diameter of the tumor, respectively.

In situ detection of apoptosis and proliferation.

Mice tumor sections were subjected to immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) and caspase-3 activation to detect apoptotic cell death.

Statistical analysis.

All values are expressed as mean plus or minus the standard deviation (SD). The statistical significance of differences between treatments was analyzed using the Student t test using GraphPad Prism analysis software; differences were considered significant when p was less than or equal to 0.05. Drug interactions were assessed by CalcuSyn 2.0 software (Biosoft), which is based on the Chou-Talay method. Combination index (CI) =1, indicates additive effect; CI < 1 indicates synergism; CI > 1 indicates antagonism.

Results

PAK4 is expressed in WM cells and its targeting by dual PAK4-NAMPT inhibitor significantly impacts WM cell viability.

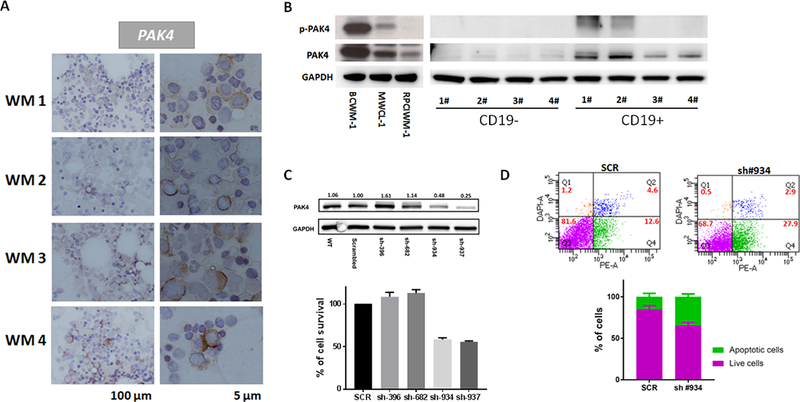

We have analyzed and observed high expression of both PAK4 and phosphorylated (p)-PAK4 Ser474 in primary cells from WM patients and WM cell lines, with significantly lower expression in normal B lymphocytes (CD19+ cells) and CD19- cells isolated from four normal donors (Figure 1A-B and Supplementary Fig. S1A). Undetectable levels of PAK4 were also previously observed in bone marrow specimens from healthy donors(9). Moreover, expression of PAK4 has been confirmed by RNA-seq in a large cohort of WM patients (Supplementary Fig. S1B). Genetic depletion of PAK4 via stable lentiviral knockdown decreased tumor cell survival proportional to the reduction in PAK4 levels in the BCWM1 cell line (Figure 1C); this effect was accompanied by induction of apoptosis (Figure 1D).

Figure 1. PAK4 is expressed and functional in WM cells.

A) Representative images of PAK4 immunocytochemistry stain in BM from 4 different WM patients. Positive staining appears in a dark brown color. Scale bars: 100 μm and 5 μm. B) Protein lysates from 3 WM cell lines, CD19+ and CD19- cells isolated from healthy individuals were analyzed for p-PAK4 and PAK4 expression by WB. GAPDH was used as loading control. C) Genetic depletion of PAK4 was achieved using 4 different pGIPZ lentiviral vectors (Dharmacon) containing the target sequence or scrambled control. Cell were collected 3 days after puromycin selection. Protein lysates were analyzed by WB, confirming decreased PAK4 protein levels in cells expressing PAK4 shRNAs compared with scrambled cells. Cell viability was evaluated by CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Assay on puromycin-selected shRNA-expressing cells in culture for 48 hours. D) Apoptotic cell death was assessed by flow cytometric analysis following DAPI and PE-AnnexinV staining in cells expressing scramble or PAK4-targeting shRNA (construct #934).

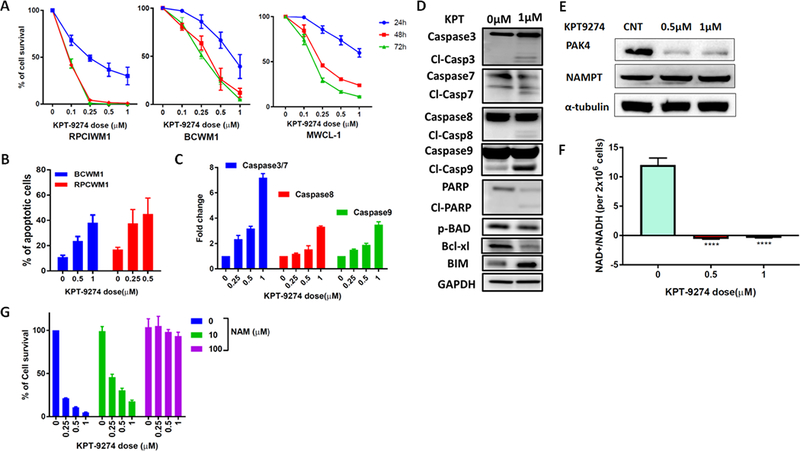

We next evaluated the effect of pharmacological inhibition of PAK4 using KPT-9274, a dual PAK4-NAMPT inhibitor. We observed a significant dose- and time-dependent decrease of WM cell viability (Figure 2A); and suppression of WM-BMSC interaction-mediated growth of WM cells (Supplementary Fig. S2A) after treatment with KPT-9274, while no effect was observed on BMSCs (data not shown). Moreover, PAK4-related biological processes such as migration, invasion and adhesion to BMSCs were negatively impacted by the inhibitor (Supplementary Fig. S2B and data not shown). The inhibition of cell viability observed after treatment with KPT-9274 was associated with a dose and time dependent induction of apoptosis (Figure 2B) via activation of effector caspases, mainly through the intrinsic apoptotic pathway and PARP cleavage (Figure 2C-D). Moreover, increased BIM levels and BCL-2 antagonist of cell death (BAD) activation, via inhibition of serine 112 phosphorylation, as well as decreased Bcl-xL levels were observed in BCWM1 cells treated with the inhibitor compared to control cells (Figure 2D).

Figure 2. KPT-9274 inhibits WM cell viability and triggers apoptotic cell death.

A) WM cell lines were treated with different concentrations of KPT-9274. Cells viability was evaluated with CellTiter-Glo at indicated time (24h-48–72 hours) and expressed as % change from untreated cells. Data represents mean ±SD of 5 experiments performed in triplicates. B) BCWM-1 and RPCIWM-1 were cultured in the absence or presence of several concentrations of KPT-9274 for 48 hours. Apoptotic cell death was assessed by flow cytometry analysis following Annexin-V and propidium iodide (PI) staining. The % of AnnexinV+ cells is shown in the graphs. C) Indicated caspase activities were evaluated in BCWM1 cells after KPT-9274 treatment for 48 hours using luminescence assay. D) Whole cell lysates from BCWM1 cells treated with control vehicle or KPT-9274 for 48 hours were subjected to Western blot analysis and probed with antibodies against indicated proteins, with GAPDH as loading control. E) BCWM1 cell were treated with different doses of KPT-9274 for 48 hours. Protein lysates were assessed by WB analysis for expression of PAK4 and NAMPT using specific Abs. α-Tubulin was used as loading control. F) Cellular NAD levels in BCWM1 treated with KPT-9274 were measured using an enzyme cyclic assay and normalized to total cell number. G) BCWM-1 cells were treated with KPT9274 (1 μM) in absence or presence of NAM (10 and 100 μM) for 48 hours. Cell viability was tested with CellTiter-Glo Luminescent Cell Assay and expressed as % change from untreated cells.

KPT-9274 allosterically binds to and destabilizes PAK4 causing its degradation. In addition, KPT-9274 also inhibits the activity of nicotinamide phosphorybosyltransferase (NAMPT), the rate limiting enzyme for NAD+ production from nicotinamide in mammalian cells. We confirmed that treatment with KPT-9274 significantly decreases PAK4 expression in WM cells, and while not impacting NAMPT protein levels, has a profound effect on cellular NAMPT activity (Figure 2E-F). Moreover, NAMPT expression was not affected by PAK4 knock down in BCWM1 cells (Supplementary Fig S1C); however, we observed a slight (but not significant) reduction of NAMPT activity in PAK4 depleted cells as compared to control cells (data not shown).

The effect of KPT-9274 treatment on NAMPT inhibition can be rescued by repletion of NAD+ through biosynthesis from nicotinamide (NAM); consistently, we found that exogenous NAM rescued KPT-9274-induced WM cell death in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 2G), further confirming the importance of NAD+-depletion in the anti-tumor effect of KPT-9274 on WM cells.

Aside NAMPT, alternative NAD+ sources available to tumors have been reported including nicotinate phosphorybosyltransferase (NAPRT), which mediates NAD+ production from nicotinic acid (NA). We have evaluated the expression of NAPRT1 in BCWM1 cells and observed no significant impact after treatment with KPT-9274 (Supplementary Fig S2C); importantly, KPT-9274-mediated inhibition of WM cell growth was largely abolished by supplementation with NA (Supplementary Fig S2D).

Dual PAK4-NAMPT inhibition exerts a potent activity against primary WM cells in vitro and in vivo in a xenograft model of human WM.

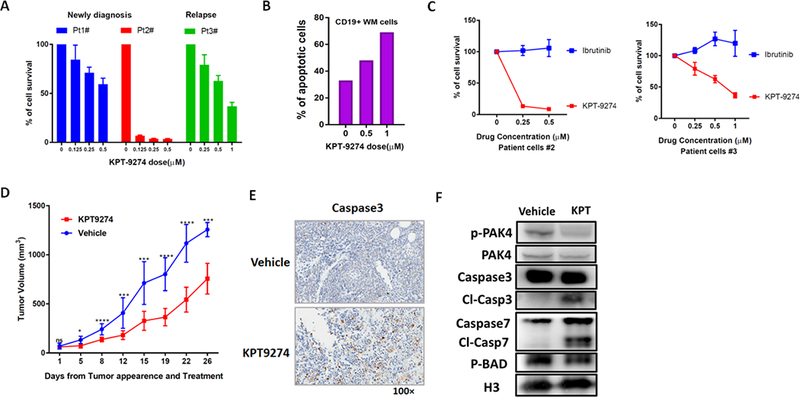

Primary WM cells were obtained from bone marrow aspirates of WM patients following CD19 positive selection. Treatment with KPT-9274 significantly inhibited cell viability and triggered apoptosis in primary WM cells from both newly-diagnosed as well as relapsed patients, in a time- and dose-dependent manner (Figure 3A-B and Supplementary Fig. S2E). Sensitivity to KPT-9274 was also observed in primary cells resistant to the BTK inhibitor Ibrutinib (Figure 3C), and in the context of the patient-derived bone marrow microenvironment (data not shown). Finally, we investigated the anti-WM effect of KPT-9274 in vivo in a murine xenograft model of human WM using BCWM1 in SCID mice. Following detection of tumors, mice were treated with either 100 mg/kg KPT-9274 or vehicle orally 5 days/week for 3 weeks. As shown in Figure 3D, treatment with KPT-9274, compared with vehicle alone, significantly inhibited WM cell tumor growth. No related toxicity was observed in mice, as determined by daily evaluation of activity and overall body weight change during the course of treatment (data not shown). Histologic examination of tumors retrieved from BCWM1-bearing mice confirmed significant tumor cell apoptosis (caspase-3 staining) (Figure 3E). Moreover, WB analysis of protein lysates from retrieved tumor cells confirmed significant induction of Caspase-7 as well as inhibition of p-BAD and decreased PAK4 expression (Figure 3F).

Figure 3. KPT-9274 impairs cell viability and promotes apoptosis in primary WM cells and displays significant activity in vivo in a xenograft murine model of WM.

A) CD19+ WM cells purified from three WM patients, were cultured in the presence of different concentrations of KPT-9274 for 48 hours. Cell viability was assessed by CTG and expressed as percent change from untreated cells. B) Apoptosis was evaluated in primary WM cells after 48h treatment with KPT-9274 by flow cytometry analysis following Annexin-V and propidium iodide (PI) staining. The % of AnnexinV+ cells is shown in the graphs. C) CD19+ primary WM cells were treated with different concentration of either KPT-9274 or Ibrutinib. Cell viability was assessed by CTG after 48 hours of treatment. D) Sublethally irradiated SCID mice were injected subcutaneously with BCWM-1 cells. Following detection of tumor, mice were randomized and treated with either KPT-9274 or vehicle orally, for 5 consecutive days/week for 3 weeks. Tumor volume was evaluated by caliper measurement. Differences between the 2 groups were evaluated using standard T-test. (* p ≤ 0.05, ** p ≤ 0.01, *** p ≤ 0.001, **** P ≤ 0.0001). E) Tumors were isolated from KPT-9274 treated and control mice and sections were evaluated by histological examinations following caspase3 staining. One representative experiment is shown. F) Tumor cells retrieved from mice were lysed in RIPA buffer and whole cell lysate subjected to WB analysis and probed with antibodies against p-PAK4, PAK4, caspase-7 and p-BAD. Histone 3 was used as loading control.

KPT-9274 impairs HR and induces DNA damage in WM cells.

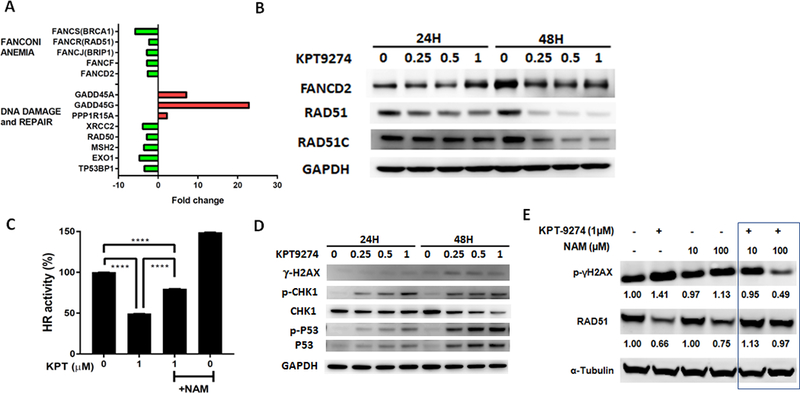

Our reanalysis of transcriptomic data in MM cells following KPT-9274 treatment (Gene Expression Omnibus accession number GSE93745) revealed a significant enrichment of DNA damage response and repair (DDR) genes in KPT-9274-treated cells compared to untreated cells (Supplementary Fig. S3A). We have therefore utilized a targeted human PCR array to elucidate the impact of KPT-9274 on the transcriptional regulation of DNA damage and repair genes in WM cells. We observed repression of DNA damage and repair genes in WM cell lines treated with KPT-9274 compared to control cells (Figure 4A). Specifically, we observed significant inhibition of Fanconi Anemia (FA)/BRCA pathway-related genes (FANCD2 and BRCA1 among others) as well as DDR genes such as RAD51. These observations were also confirmed by qPCR (Supplementary Fig. S3B) and at the post-transcriptional level by WB analysis, as observed for RAD51 and other components of the homologous recombination (HR) repair machinery (Figure 4B). This effect was accompanied by inefficient HR-mediated repair activity (Figure 4C), along with induction of DNA damage (assessed by γH2AX) and p53 activation in both KPT-9274-treated (Figure 4D). These observations correlate with the described activity of NAD on DNA damage and repair (10,14,15). Consistent with these findings, we also observed that nicotinamide and nicotinic acid supplementation partly rescued the effect of KPT-9274 on DNA damage and repair (Figure 4C-E and Supplementary Fig. S3C-D).

Figure 4. KPT-9274 impacts DDR pathways in WM cells.

A) Total RNA from control or KPT-9274-treated BCWM1 cells was evaluated by Human DNA Damage Signaling Pathway RT2 Profiler™ PCR Array to profile the expression of 84 genes involved in DNA damage signaling pathways. The relative expression level compared to control cells for each gene is plotted relative in the graph. B-D) Whole cell lysates from BCWM-1 cells treated with several concentrations of KPT-9274 for 24 and 48 hours were subjected to WB analysis and probed with indicated antibodies. GAPDH was used as loading control. C) Relative HR activity of BCWM-1 cells treated with KPT-9274 in absence or presence of nicotinamide (NAM, 100 μM). E) Whole cell lysates from BCWM-1 treated with KPT9274 (1 μM) in absence and presence nicotinamide (10 and 100 μM) for 48 hours, were subjected to WB analysis and probed with indicated antibodies.

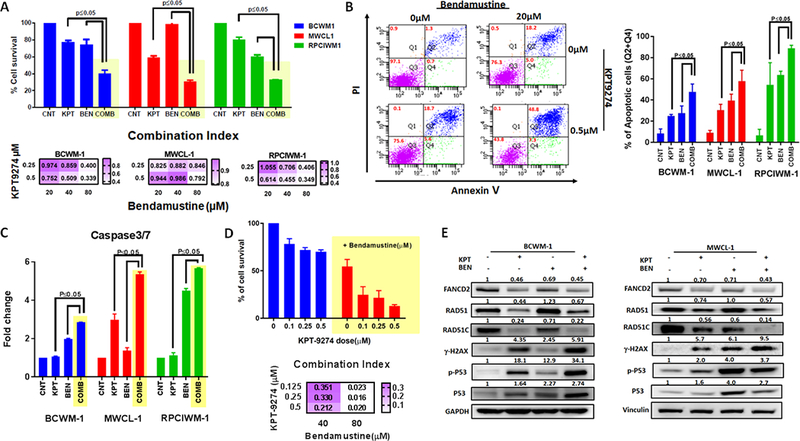

Dual PAK4-NAMPT inhibition potentiates sensitivity to bendamustine via synergistic modulation of DDR markers.

Fanconi anemia and DDR pathways have been implicated in resistance to DNA alkylating agents(16–19). Since bendamustine is currently one of the main drugs used in WM patients(20–22), we have explored the potential of KPT-9274 to impact sensitivity of WM cells to bendamustine. WM cells were therefore simultaneously treated with different concentration of KPT-9274 and bendamustine. The combination treatment resulted in significant time- (data not shown) and dose-dependent inhibition of cell viability (Figure 5A); isobologram and combination index analysis revealed strong synergism of the combination as compare to single agents, with a combination index (CI)˂1.0 at all tested doses (Figure 5A and Supplementary Fig. S4A). The synergistic inhibition of WM viability was accompanied by significant induction of apoptotic cell death (Figure 5B) and activation of caspase-3/7 (Figure 5C) in combined versus single-agent therapy; and the effect was partially rescued by NA supplementation (Supplementary Fig. S4B). Importantly, neither single agent nor the combination triggered death of healthy donor PBMCs, suggesting a favorable therapeutic index (Supplementary Fig. S4C). Interestingly, in PAK4-depleted WM cells, treatment with bendamustine significantly increased the rate of early and late apoptosis compared to scrambled control cells (Supplementary Fig. S4D). Importantly, a potent synergistic anti-WM activity of KPT-9274 in combination with bendamustine was observed in primary WM patient cells, with a CI ˂1.0 with all tested doses (Figure 5D). Finally, DNA damage markers were significantly affected by the combination regimen when compared with either drug alone (Figure 5E); the effect was partially rescued by NA supplementation (Supplementary Fig. S4E). A similar synergism was observed in WM cells treated with KPT-9274 in combination with the DNA-damaging agent melphalan (Supplementary Fig. S5).

Figure 5. KPT-9274 induces synergistic growth inhibitory effects in combination with bendamustine in WM cells in vitro.

A) WM cell lines were simultaneously treated with KPT-9274 and/or bendamustine for 48 hours. Cells viability was tested with CellTiter-Glo and expressed as % of cell viability from untreated cells. Data represents mean ±SD of 3 experiments performed in triplicates (upper panel). The interaction between KPT-9274 and bendamustine was analyzed using the CalcuSyn software program (Biosoft, Ferguson, MO) based on the Chou-Talalay method. The Combination index (CI) is represented as heatmaps (lower panel). CI = 1 indicates additive effects; CI < 1 indicates synergism and CI > 1 indicates antagonism. B) Apoptotic cell death was assessed by flow cytometric analysis following AnnexinV and PI staining in single treated with single agents or combination. One representative experiment is shown on the left panel, while the % of AnnexinV+ in different WM cell lines following treatment is shown on the right panel. Data represent mean ±SD of two experiments. C) Caspase 3/7 activation was evaluated after combination treatment using luminescence assay. D) Primary CD19+ cells were cultured in the presence of several concentrations of KPT-9274 in combination with bendamustine for 48 hours. Cell viability was assessed by CTG uptake and presented as % compared to control cells (upper panel). Drug interactions were assessed by CalcuSyn 2.0 software (Biosoft) and CIs are represented in the heatmap (lower panel). E) Whole cell lysates from BCWM-1 (left panel) and MWCL1 (right panel) cell lines treated with control, or single agents or combination were subjected to WB analysis and probed with indicated antibodies.

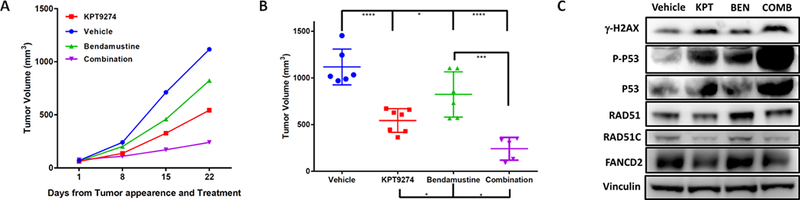

KPT-9274 and bendamustine synergize to suppress human WM cell growth in vivo.

Having shown that combined KPT-9274 plus bendamustine induced synergistic apoptosis in WM cells in vitro, we next examined the in vivo efficacy of the combination in a human xenograft mouse model using BCMW.1 cells injected s.c. in SCID mice. After tumor development (approximately 3 weeks from cells injection), mice were treated with vehicle, KPT-9274 (100 mg/kg, daily for 5 days a week, administered orally), bendamustine (25 mg/kg, one injection intraperitoneally/week for two weeks) as single agents or in combination. As seen in Figures 6A and B, the combination of bendamustine with KPT-9274 induced a significant reduction in tumor growth compared to mice receiving vehicle or either single agents. The combination did not have increased toxicity (data not shown). Furthermore, WB analysis of cell lysates from retrieved tumors confirmed the effect of the combination on DDR pathway (Figure 6C).

Figure 6. Combination therapy results in tumor shrinkage in vivo compared to single agent therapy.

A) Sub-lethally irradiated SCID mice were subcutaneously inoculated with BCWM-1 WM cell line. Treatment started following detection of tumor (approximately 2 weeks from cell injection). Mice were treated either with vehicle (100mg/kg once/daily, 5days/week), KPT-9274 (100mg/kg once/daily, 5days/week), bendamustine (25mg/kg, once/weekly, for 2 weeks) and a combination of KPT-9274 and bendamustine. Tumors were measured in two perpendicular dimensions weekly. B) Comparison of tumor volume in control and treated mice 3 weeks after initial assessment of tumor appearance and start of treatment. C) Whole cell lysate from tumor cells retrieved from mice was subjected to WB analysis and probed with antibodies against with indicated antibodies. Vinculin was used as loading control.

Discussion

We have recently shown significant biological and functional role of PAK4, and the therapeutic value of a dual PAK4-NAMPT inhibitor (KPT-9274) in MM. Based on the promising findings in MM and other malignancies, including PDAC, Renal Cell Carcinoma (RCC), triple negative breast cancer, and B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL)(9,23–27), we here characterize and report a significant antitumor effect of KPT-9274 in WM, including ibrutinib-resistant primary patients WM cells. In this study, we confirmed the dual inhibition properties of KPT-9274, via its impact on both PAK4 protein expression and cellular NAD+ levels in WM cells. Co-inhibition of these targets via KPT-9274 led to synergistic anti-tumor effects through energy depletion, inhibition of proliferation, and ultimately apoptosis in WM cells. Rescue experiments with nicotinamide and nicotinic acid confirmed the importance of NAD+ depletion for the growth inhibitory effect exerted by KPT-9274 on WM cells

Recent studies have implicated activity of PAK family members as well as NAD+ in DNA damage and repair(15,28–30). We have observed a significant induction of DNA damage along with inhibition of DNA repair in WM cells after treatment with KPT-9274. Interestingly, induction of DNA damage was also observed in PAK4 knockdown cells (data not shown). The intrinsic apoptotic pathway is a major mechanism of cell death in response to DNA damage, and the p53 tumor suppressor is the primary regulator of apoptosis in response to DNA damage(31,32). We have observed a significant increase in the phosphorylation of Chk1, leading to the activation of p53 in cells treated with KPT-9274. At the same time, KPT-9274 significantly affected expression of genes involved in the FA/BRCA as well as HR-mediated repair sustaining the induction of DNA damage. In line with the hypothesis that defective NAD+ synthesis is responsible for the increased DNA damage observed upon KPT-9274 treatment in WM cells, we found that exogenously added NAD+ reduced DNA damage in WM-treated cells, and partly rescued the inhibition of HR.

FA/BRCA and DDR pathways have been shown to affect sensitivity to alkylating agents(16–19), and our mechanistic studies indeed demonstrated that dual PAK4 and NAMPT inhibition by KPT-9274 in WM cells sensitizes them to the activity of alkylating agents, such as melphalan or bendamustine. The combination treatment resulted indeed in a synergistic time- and dose-dependent inhibition of cell viability in cell lines and primary WM cells, while sparing the viability of healthy PBMC. We also observed a synergistic induction of apoptosis and caspase activation following treatment with combined versus single-agent therapies with greater induction of DNA damage. In addition, we confirmed the anti-WM activity of this combination in vivo in mice xenografted with BCWM1. We believe these results are highly significant, considering that bendamustine is an approved agent for treatment of NHL and WM (33), (20–22). Importantly, we show here for the first time the impact of targeting DDR and HR pathways in WM.

In summary, we report significant anti-proliferative activity of dual PAK4-NAMPT inhibition in WM cells, with induction of apoptosis, DNA-damage response and FA/BRCA pathway disruption and a strong synergistic activity in combination with DNA damaging agents such as bendamustine; suggesting KPT-9274 as a novel therapeutic strategy in WM as monotherapy or in combination with alkylating agents.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by NIH grants PO1–155258 (MF, NCM) and P50–100707 (NCM); Department of Veterans Affairs Merit Review Award 1 I01BX001584–01 (NCM).

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: William Senapedis and Erkan Baloglu are employees of Karyopharm Therapeutics Inc. All other authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Translational Relevance:

Our study provides the framework for the clinical evaluation of novel allosteric PAK4-NAMPT inhibitor in WM patients, alone or in combination with DNA-damaging agents.

References

- 1.Hunter ZR, Xu L, Yang G, Zhou Y, Liu X, Cao Y, et al. The genomic landscape of Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia is characterized by highly recurring MYD88 and WHIM-like CXCR4 mutations, and small somatic deletions associated with B-cell lymphomagenesis. Blood 2014;123(11):1637–46 doi 10.1182/blood-2013-09-525808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hunter ZR, Xu L, Yang G, Tsakmaklis N, Vos JM, Liu X, et al. Transcriptome sequencing reveals a profile that corresponds to genomic variants in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Blood 2016;128(6):827–38 doi 10.1182/blood-2016-03-708263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yang G, Zhou Y, Liu X, Xu L, Cao Y, Manning RJ, et al. A mutation in MYD88 (L265P) supports the survival of lymphoplasmacytic cells by activation of Bruton tyrosine kinase in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Blood 2013;122(7):1222–32 doi 10.1182/blood-2012-12-475111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dimopoulos MA, Kastritis E, Owen RG, Kyle RA, Landgren O, Morra E, et al. Treatment recommendations for patients with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia (WM) and related disorders: IWWM-7 consensus. Blood 2014;124(9):1404–11 doi 10.1182/blood-2014-03-565135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunter ZR, Yang G, Xu L, Liu X, Castillo JJ, Treon SP. Genomics, Signaling, and Treatment of Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia. Journal of clinical oncology : official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2017;35(9):994–1001 doi 10.1200/jco.2016.71.0814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Abo A, Qu J, Cammarano MS, Dan C, Fritsch A, Baud V, et al. PAK4, a novel effector for Cdc42Hs, is implicated in the reorganization of the actin cytoskeleton and in the formation of filopodia. The EMBO journal 1998;17(22):6527–40 doi 10.1093/emboj/17.22.6527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lu H, Liu S, Zhang G, Bin W, Zhu Y, Frederick DT, et al. PAK signalling drives acquired drug resistance to MAPK inhibitors in BRAF-mutant melanomas. Nature 2017;550(7674):133–6 doi 10.1038/nature24040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Radu M, Semenova G, Kosoff R, Chernoff J. PAK signalling during the development and progression of cancer. Nature reviews Cancer 2014;14(1):13–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fulciniti M, Martinez-Lopez J, Senapedis W, Oliva S, Lakshmi Bandi R, Amodio N, et al. Functional role and therapeutic targeting of p21-activated kinase 4 in multiple myeloma. Blood 2017;129(16):2233–45 doi 10.1182/blood-2016-06-724831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiarugi A, Dolle C, Felici R, Ziegler M. The NAD metabolome--a key determinant of cancer cell biology. Nature reviews Cancer 2012;12(11):741–52 doi 10.1038/nrc3340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cea M, Cagnetta A, Fulciniti M, Tai YT, Hideshima T, Chauhan D, et al. Targeting NAD+ salvage pathway induces autophagy in multiple myeloma cells via mTORC1 and extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK1/2) inhibition. Blood 2012;120(17):3519–29 doi 10.1182/blood-2012-03-416776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cea M, Cagnetta A, Acharya C, Acharya P, Tai YT, Yang C, et al. Dual NAMPT and BTK Targeting Leads to Synergistic Killing of Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia Cells Regardless of MYD88 and CXCR4 Somatic Mutation Status. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2016;22(24):6099–109 doi 10.1158/1078-0432.Ccr-16-0630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fulciniti M, Tassone P, Hideshima T, Vallet S, Nanjappa P, Ettenberg SA, et al. Anti-DKK1 mAb (BHQ880) as a potential therapeutic agent for multiple myeloma. Blood 2009;114(2):371–9 doi 10.1182/blood-2008-11-191577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fouquerel E, Sobol RW. ARTD1 (PARP1) activation and NAD(+) in DNA repair and cell death. DNA repair 2014;23:27–32 doi 10.1016/j.dnarep.2014.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tummala KS, Gomes AL, Yilmaz M, Grana O, Bakiri L, Ruppen I, et al. Inhibition of de novo NAD(+) synthesis by oncogenic URI causes liver tumorigenesis through DNA damage. Cancer cell 2014;26(6):826–39 doi 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bouwman P, Jonkers J. The effects of deregulated DNA damage signalling on cancer chemotherapy response and resistance. Nature reviews Cancer 2012;12(9):587–98 doi 10.1038/nrc3342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Enoch T, Norbury C. Cellular responses to DNA damage: cell-cycle checkpoints, apoptosis and the roles of p53 and ATM. Trends in biochemical sciences 1995;20(10):426–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fan S, el-Deiry WS, Bae I, Freeman J, Jondle D, Bhatia K, et al. p53 gene mutations are associated with decreased sensitivity of human lymphoma cells to DNA damaging agents. Cancer research 1994;54(22):5824–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yarde DN, Oliveira V, Mathews L, Wang X, Villagra A, Boulware D, et al. Targeting the Fanconi anemia/BRCA pathway circumvents drug resistance in multiple myeloma. Cancer research 2009;69(24):9367–75 doi 10.1158/0008-5472.Can-09-2616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tedeschi A, Picardi P, Ferrero S, Benevolo G, Margiotta Casaluci G, Varettoni M, et al. Bendamustine and rituximab combination is safe and effective as salvage regimen in Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Leukemia & lymphoma 2015;56(9):2637–42 doi 10.3109/10428194.2015.1012714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Treon SP. How I treat Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia. Blood 2015;126(6):721–32 doi 10.1182/blood-2015-01-553974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Treon SP, Hanzis C, Tripsas C, Ioakimidis L, Patterson CJ, Manning RJ, et al. Bendamustine therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory Waldenstrom’s macroglobulinemia. Clinical lymphoma, myeloma & leukemia 2011;11(1):133–5 doi 10.3816/CLML.2011.n.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Abu Aboud O, Chen CH, Senapedis W, Baloglu E, Argueta C, Weiss RH. Dual and Specific Inhibition of NAMPT and PAK4 By KPT-9274 Decreases Kidney Cancer Growth. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2016;15(9):2119–29 doi 10.1158/1535-7163.Mct-16-0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rane C, Senapedis W, Baloglu E, Landesman Y, Crochiere M, Das-Gupta S, et al. A novel orally bioavailable compound KPT-9274 inhibits PAK4, and blocks triple negative breast cancer tumor growth. Scientific reports 2017;7:42555 doi 10.1038/srep42555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Aboukameel A, Muqbil I, Senapedis W, Baloglu E, Landesman Y, Shacham S, et al. Novel p21-Activated Kinase 4 (PAK4) Allosteric Modulators Overcome Drug Resistance and Stemness in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Molecular cancer therapeutics 2017;16(1):76–87 doi 10.1158/1535-7163.Mct-16-0205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Takao S, Chien W, Madan V, Lin DC, Ding LW, Sun QY, et al. Targeting the vulnerability to NAD(+) depletion in B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 2018;32(3):616–25 doi 10.1038/leu.2017.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mohammad RM, Li Y, Muqbil I, Aboukameel A, Senapedis W, Baloglu E, et al. Targeting Rho GTPase effector p21 activated kinase 4 (PAK4) suppresses p-Bad-microRNA drug resistance axis leading to inhibition of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma proliferation. Small GTPases 2017:0 doi 10.1080/21541248.2017.1329694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Motwani M, Li DQ, Horvath A, Kumar R. Identification of novel gene targets and functions of p21-activated kinase 1 during DNA damage by gene expression profiling. PloS one 2013;8(8):e66585 doi 10.1371/journal.pone.0066585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Advani SJ, Camargo MF, Seguin L, Mielgo A, Anand S, Hicks AM, et al. Kinase-independent role for CRAF-driving tumour radioresistance via CHK2. Nature communications 2015;6:8154 doi 10.1038/ncomms9154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li DQ, Nair SS, Ohshiro K, Kumar A, Nair VS, Pakala SB, et al. MORC2 signaling integrates phosphorylation-dependent, ATPase-coupled chromatin remodeling during the DNA damage response. Cell reports 2012;2(6):1657–69 doi 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Horn HF, Vousden KH. Coping with stress: multiple ways to activate p53. Oncogene 2007;26(9):1306–16 doi 10.1038/sj.onc.1210263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paull TT, Rogakou EP, Yamazaki V, Kirchgessner CU, Gellert M, Bonner WM. A critical role for histone H2AX in recruitment of repair factors to nuclear foci after DNA damage. Current biology : CB 2000;10(15):886–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheson BD, Rummel MJ. Bendamustine: rebirth of an old drug. J Clin Oncol 2009;27(9):1492–501 doi 10.1200/jco.2008.18.7252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.