Abstract

Mediation analysis allows the examination of effects of a third variable in the pathway between an exposure and an outcome. The general multiple mediation analysis method, proposed by Yu et al, improves traditional methods (eg, estimation of natural and controlled direct effects) to enable consideration of multiple mediators/confounders simultaneously and the use of linear and nonlinear predictive models for estimating mediation/confounding effects. In this paper, we extend the method for time-to-event outcomes and apply the method to explore the racial disparity in breast cancer survivals. Breast cancer is the most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death among women of all races. Despite improvement of survival rates of breast cancer in the US, a significant difference between white and black women remains. Previous studies have found that more advanced and aggressive tumors and less than optimal treatment may explain the lower survival rates for black women as compared to white women. Due to limitations of current analytic methods and the lack of comprehensive data sets, researchers have not been able to differentiate the relative effect each factor contributes to the overall racial disparity. We use the CDC-funded Patterns of Care study to examine the determinants of racial disparities in breast cancer survival using a novel multiple mediation analysis. Using the proposed method, we applied the Cox hazard model and multiple additive regression trees as predictive models and found that all racial disparity in survival among Louisiana breast cancer patients were explained by factors included in the study.

Keywords: mediation analysis, multiple additive regression trees, pattern of care, racial disparity, survival analysis

1 ∣. INTRODUCTION

Mediation effect refers to the effect conveyed by an intervening variable (eg, mediator) to an observed relationship between an exposure and a response variable of interest. In 1929, Robert S. Woodworth introduced the expression Stimulus-Organism-Response (S – O – R) to describe the pathway between a stimulus and a response. This concept has then been expanded to many fields such as social science research, prevention study, behavior research, and epidemiology study, where investigators are interested in discovering not only the relationship between an exposure variable and a response variable but also the mechanism underlying the relationship. For example, it has been well established that low socioeconomic status (SES) is associated with poor health status.1 However it is not decided whether the health disparities come from the differences in individual behavior, or from the various living and working environments among people from different SES levels. To understand this distinction, investigators would need to differentiate and quantify mediation effects from different risk factors so that efficient interventions can be carried out using limited resources.

There are generally two settings for inferences on mediation effects. One is through linear models,2-5 and the other is on the counterfactual framework.6-8 However, the linear model method is not easily adaptable to separate multiple mediation effects when Y or M are not continuous and when the relationships cannot be fitted with linear regressions.6 The conter-factual framework fits best when the exposure variable is binary; otherwise, it is difficult to choose a referral exposure level when the exposure variable is multi-categorical or continuous.9,10 For example, Vanderweele and Vansteelandt11 proposed a method that uses weights to control for other covariates in calculating mediation effects. Their proposed method can be used to consider joint effects of multiple mediators, but it is limited to binary exposures or exposures with a small number of levels since a start and an ending value of the exposure variable have to be set up for the analysis. Recently, mediation analysis has been further developed by Imai et al12,13 such that more general models, for example, generalized linear models and generalized additive models, can be used to fit relationships among variables. By their method, general models are fitted for the outcome and mediators, based on which potential values for outcome and mediators can be simulated, and in turn to estimate the mediation effects. Common as in the conterfactual framework, the method focuses mainly on computing mediation effect between two treatment values of the exposure. Steen et al14 proposed a weighting method to estimate mediation effects for multiple mediators through a Monte Carlo method. The authors explained in detail on using the method when there are two mediators with different potential causal paths. However, only results from logistic regression were considered for binary outcomes. Moreover, the method has to be applied for specific conceptual models. Yu et al15-17 further developed the concept of mediation effects and the inference method based on the changing rate in outcome. Rather than on a contrast of the outcome between two exposure values, the proposed mediation effects are defined on the changing rate of the outcome. Therefore, the measurement can be generalized to multi-categorical or continuous exposure variables. Moreover, the measure is invariant to the unit of the value of the exposure, and a base value of the exposure variable is not required. In summary, the mediation analysis of Yu et al15 meets the following requests: 1)the response, treatment variables and mediators can take any formats: continuous, binary or multi-categorical; 2)transformations among predictor, covariates and mediators are allowed to account for potential nonlinear associations and interactions among variables; 3) joint effects from highly correlated variables can be calculated; 4) mediation effects from different mediators are differentiable, as long as no mediator is causally prior to any others; and 5) inferences on mediation effects can be made (calculate estimates, variances, and confidence intervals). In this paper, we further extend the method to deal with survival outcomes. Previous mediation studies on survival data have either focused on a single mediator or was based on complex process.18 For example, Huang and Yang19 extended the mediation analysis to survival outcome with multiple mediators by specifically defining indirect and direct effects for a two-mediator sequential path. Their method is confined to the two-mediator sequential path and has to specify the base and ending values of the exposure variable. Moreover, the mediation effects were deducted for three types of survival models only. Vandenberghe et al20 proposed to use time-to-event mediation techniques to identify surrogate markers. In their analysis, the concepts of natural mediation effects were used. As will be discussed in Section 3.1, natural mediation effects are based on very rigorous assumptions. We develop the mediation analysis with time-to-event outcomes that can deal with multiple mediators and use general survival models. The developed method is applied to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) supported Pattern-of-Care (PoC) study to explore the racial disparity in survival among female patients with breast cancer. In the study, the exposure variable is race. The interpretation of racial disparity is discussed in Section 3.3. The mediation method developed for this study can deal with multiple risk factors and differentiate indirect effects from different mediators/confounders that explain the racial disparity. Furthermore, the proposed method can make inferences on the joint mediation effects from risk factors that are highly correlated. We further expand the R package mma such that it can use nonlinear and linear survival models to make inferences on mediation effects for survival outcomes.

The rest paper is organized as follows: the background of a motivation example, PoC study and its data description, is introduced in Section 2. Section 3 reviews mediation analysis methods, and proposes a novel mediation analysis and algorithms for time-to-event outcome. We also introduce the R package, mma, for data analysis. Results for the exploration of racial disparities in breast cancer survival are discussed in Section 4. In Section 5, we conducted simulations to test the proposed method in differentiating mediation effects when mediators are highly correlated and when there is nonlinear relationship among variables, and finally, we make conclusions, discuss limitations of the research, and point out future research directions in Section 6.

2 ∣. PATTERN OF CARE STUDY

Breast cancer is the most commonly diagnosed cancer among American women of all races. It is also the second leading cause of cancer death. Due to advanced screening methods for early stage breast cancer detection and improved treatments, the overall death rate of breast cancer in the United States (US) has decreased since 1990s. However, when compared with white women, African American women endured higher recurrence and death rates from breast cancer although they had a lower incidence rate.21-23 Understanding the factors that account for these disparities is central to the goals laid out by the National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NIMHD), National Cancer Institute (NCI), and Department of Health & Human Services (DHHS) in the Healthy People 2020 report. A variety of risk factors, including environmental, treatment, individual behavioral, and tumor related factors, have been identified that contribute to disparities in breast cancer.24-29

In response to findings reported by the Institute of Medicine that cancer patients do not consistently receive care known to be effective for their conditions, the National Program of Cancer Registries of the Centers of Disease Control and Prevention conducted a series of studies referred to as Pattern of Care studies (PoC), including the PoC-Breast and Prostate (BP) study that collected complete health care information and tumor characteristic information for female breast cancer patients. The study collected patient care and follow-up information from breast cancer patients and subsequently linked with data from a number of sources, including 1) census data for social-environmental information, 2) hospital and physician files for measures of health systems, 3) hospital, provider, and Medicare files for obtaining additional information on comorbidity and adjuvant treatment. These rich data sources provide the opportunity to jointly consider a more encompassing set of risk factors for exploring the racial disparity in breast cancer survival.

We use the data set collected by the Louisiana Tumor Registry for the PoC-BP study, which re-abstract medical records of 1453 Louisiana non-Hispanic white and black women diagnosed with invasive breast cancer in 2004.15 All patients were followed up for five years or until death, whichever is shorter. We found that the odds of dying of breast cancer within three years for black women was significantly higher than that for white patients (OR = 2.03, CI : (1.468, 2.809)). To explain the racial disparity in breast cancer survival, we extended the mediation analysis method to include linear and nonlinear survival models and applied the method on the PoC study to separate effects from different risk factors of various formats (continuous, binary, or categorical). The variables used in this study and their values, format, and data sources are listed in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

List of variables and data sources

| Group | Variable Name (Values/Formats) | Data Source |

|---|---|---|

| Outcome | date of last contact, vital status, cause of death (right-censored data) |

Cancer registry, Pattern of Care (PoC) study |

| Patient Information | insurance status (private, public, no) race (black, white) age at diagnosis (continuous, years) marital status (single, married, separated/divorced/widowed) BMI (continuous, kg/m2) comorbidity (no/mild, moderate, severe) |

Hospital discharge sheets, Medical records, Cancer registry |

| Tumor Characteristics | tumor grade (categorical) lateral (left, right) tumor size (continuous, mm) lymph nodes involvement (yes, no) extension (from the primary and distant metastases: yes, no) cancer type (four types by ER/PR, her2 (+,−)) stage (SEER stage 2000) |

Cancer registry, PoC |

| Environment Variable | poverty (≥ 20% vs < 20% households below poverty) education (≥ 25% vs < 25% adults with less than high school) residence area (rural, mixed, urban) employment (≥ 66% vs < 66% adults unemployed) |

Census |

| Treatment Information | surgery (no, lumpectomy, mastectomy) radiation (no, yes) radiation (no, yes) chemo-therapy (no, yes) hormonal (no, yes) |

PoC |

| Health Care Facility | bed size (continuous) hospital ownership (public, private) teaching hospital (yes, no) COC status (yes, no) |

American Hospital Association, PoC Study |

3 ∣. METHODS AND INTERPRETATION

A third variable can intervene in the relationship between an explanatory variable (eg, race) and a response variable (eg, survival/hazard rate) through many forms. The two major formats are mediation and confounding. Mediation effects assume a causal relationship from the exposure to mediators to the outcome, while confounding effects do not make this assumption. Although they are conceptually distinctive, MacKinnon et al30 claimed that these effects are statistically similar in the sense that all of them measure the change of association between the explanatory and response variables when considering a third variable. Therefore, the statistical methods developed for mediation framework can be used for confounding effect analysis, although the scientific interpretations of the analysis might be different. The effect carried by a third variable is called indirect effect. Our purpose is to use the mediation analysis to explore the racial disparity in breast cancer survival. In this section, we will first review the general mediation analysis method, discuss its extensions for the purpose of this analysis, and then discuss how to interpret the “effect of race.”

3.1 ∣. General definitions of mediation/confounding effects for multiple mediators/confounders

Yu et al15 proposed general definitions of mediation/confounding effects. These definitions are related to conventional mediation analysis but are more general in that they are consistent for different types of predictors or outcomes.

The definitions are based on three basic assumptions that were widely used in defining mediation effects:

A1 No-unmeasured-confounder for the exposure-outcome relationship;

A2 No-unmeasured-confounder for the mediator-outcome relationship;

A3 Mediator Mi is not causally prior to other mediators M−i.

Given other factor(s) Z, Yu et al15 define the mediation/confounding effects through the rate of change in Y when X changes from x by a u* unit, where u* is the smallest unit of X, such that u* + x ∈ domain(X), for any x ∈ domain(X). Based on the notations, the average total effect is defined as

and the average direct effect not through Mi is

The definition of direct effect not from Mi is analogous to the natural direct effect that allows for natural variation in the levels of the mediator between subjects. However, instead of allowing Mi to vary conditionally on a fixed level of the predictor, we allow it to vary at its marginal distribution. Intuitively, the average direct effect not from Mi measures the average changing rate in the outcome Y when the exposure variable X changes from x* to x* + u and the relationship between X and Mi is “broken.” That is, when X changes, the distribution of Mi (marginal distribution) does not change with X, while distributions for all other mediators change with X (conditional distributions). In such cases, the “direct effect of X on Y not from Mi” includes the direct effect of X on Y and the indirect effects through mediators other than Mi. The definition of indirect effect through Mi is defined straightforwardly as AIE(Mi∣Z) = ATEz – ADE\Mi∣Z. As is defined, the mediation analysis does not require the assumption of no measured or unmeasured effect of the exposure that confounds the mediator outcome relationship. Interested readers are referred to the work of Fan.31

Compared with conventional definitions of the mediation/confounding effects that look at the average differences in the expected Y when X changes from X = a and X = a*,15 defined mediation/confounding effects in terms of the changing rate of Y with X. The motivation is that first the exposure levels a and a* do not have to be preset, and second, the unit for mediation/confounding effects is the unit of Y per unit of X but not just the unit of Y. In such case, the mediation/confounding effects would not change with the unit of X, nor with how much X changes from one level to another. With these properties, the mediation/confounding effects are generalized from binary to continuous predictors under the counterfactual framework.15 have shown that the mediation/confounding effects based on the proposed definitions are equivalent to the conventional mediation/confounding effects when the response variable and all mediators are continuous, and linear regressions are used to fit relationships among variables. They also established the relationship between the proposed definitions and the natural direct or indirect effects for binary predictors. For example, when X is binary (take the values 0 or 1), the natural direct effect from X to Yis defined as δ(0) ≡ E[Yi(1, Mi(0)) – Yi(0, Mi(0))] or δ(1) ≡ E[Yi(1, Mi(1)) – Yi(0, Mi(1))], where the mediators are fixed at X = 0 or X = 1. The assumption is that δ(0) = δ(1). Otherwise, there could be multiple measurements of indirect effect or direct effect when X is fixed at different values. This assumption brings in challenges to generalizing the mediation analysis to multi-categorical or continuous exposures.15 relaxes this assumption. They have show that their defined direct effect for binary X is P(X = 0)· δ(0) + P(X = 1) · δ(1), a weighted combination of δ(0) and δ(1).

Applying the definitions to the special case in our analysis, the exposure variable is the binary race (white, X = 0 or black, X = 1). The average total effect is E(Y∣Z, X = 1) – E(Y∣Z, X = 0), and the average direct effect of X on Y not through Mi is ADE\Mj∣z = DE\Mj∣z(0) = Emj{EM−j∣X=1[E(Y∣Z, Mj = mj, M−j, X = 1)] – EM−j∣X=0[E(Y∣Z, Mj = mj, M−j, X = 0)]}.

3.2 ∣. Non/Semiparametric mediation analysis for survival outcomes with binary exposure

The definitions proposed by Yu et al15 is promising in that the indirect effects contributed by different mediators are separable, which enables comparisons of the relative effects carried by different risk factors on racial disparities. Furthermore, more general predictive models, including multivariate additive regression trees (MART), and Cox proportional hazards models can be used in addition to generalized linear models to fit variable relationships. In this section, we propose two algorithms to calculate mediation effects with survival outcomes.

When the outcome is time-to-event with right censoring, Algorithms 1 and 2 that derived directly from the definitions of mediation/confounding effects provide the method to calculate mediation/confounding effects when the exposure variable is binary with the assumption that the sample size at each exposure level is large. With these algorithms, the relationship between the outcome and all variables can be fitted using hazards models (linear or nonlinear), and the relationships among other variables can be fitted using any parametric or nonparametric models. More general mediation analysis with any types of exposures or outcomes is discussed by Yu and Li,16 where the R package, mma, built to make inferences on mediation/confounding effects using the algorithms is also discussed.

The algorithms are based on two assumptions. First, the mediators for the ith subject have a multivariate normal distribution of the form

| (1) ∣ |

The mean of Mki is estimated individually by ĝk(xi, zi). ĝ are the functions to estimate the mean of M condition on X and other potential covariates. Smoothing splines and GLM can be chosen in the package mma to build ĝ. The variance-covariance matrix is estimated through the residuals Mki – ĝk(xi, zi). When the kth mediator/confounder, Mk, is categorical with K categories, ĝk is a vector of k – 1 elements, where each element gives the estimated probability of one category except for the reference group. Fan31 described the details to construct .

Let Yi denote the observed time (either censoring or event time) for subject i. Let Ci be the indicator that the time corresponds to an event (ie, Ci = 1 for event and Ci = 0 for censoring). We further assume that the prediction model of Y has the form

| (2) ∣ |

where f can be any hazard or survival models. In the R package mma, MART and Cox proportional hazard models can be chosen to build f. For simplicity, we omit the covariates z in the following algorithms.

Algorithm 1. Estimate the total effect:

Generate (M1j1, …, Mpj1)T given X = 0 from Equation (1) for j = 1, …, N.

Generate (M1j2, …, Mpj2)T given X = 1 from Equation (1) for j = 1, …, N.

.

When the mediator/confounder Mk is categorical, generations from Equation (1) give the probability vector of Mk belonging to each group, based on which Mk is drawn with a multinomial distribution. Note that the total effect is in terms of the log of hazards. Therefore, it is explained as the average differences in the log(hazard) between different levels of X. Other mediation/confounding effects calculated from the proposed algorithms should be explained similarly.

Algorithm 2.Estimate the direct effect not through Mk:

Use the samples generated by Steps 1 and 2 of Algorithm 1.

Combine the vectors and and randomly permute the combined vector, denote the new vector as . forms a sample of Mk from its marginal distribution.

DE\Mk is estimated by .

Due to the randomness brought in by sampling, the two algorithms are repeated, and the average results from the repetitions are estimates of mediation/confounding effects.

3.3 ∣. Interpret the racial disparity

In this paper, we would like to explain the racial disparity in survival rate observed among patients diagnosed with breast cancer in 2004 at Louisiana. We demonstrate the proposed mediation analysis method to differentiate the indirect effects from a wide range of potential mediators/confounders that account for racial disparities in breast cancer survival. There are controversies in interpreting the “race effect.” It is impossible to establish “causal effect of race.” However, “effect of race” can be defined. VanderWeele and Robinson32 extensively discussed the challenges and different interpretations of race effect. We use their interpretation where “the effect of race involves the joint effects of race-associated physical phenotype (eg, skin color),32 parental physical phenotype, genetic background, and cultural context when such variables are thought to be hypothetically manipulable and if adequate control for confounding were possible.” Combined with the method proposed above, direct effect of race is interpreted as the remaining racial disparity if distributions of various risk factors across racial groups could be equalized. The indirect effect from a certain risk factor is the change in the health disparity if the distributions of the risk factor can be set as the same across racial groups, while distributions for other risk factors are kept as observed.

With this interpretation, the hypothetical manipulation on race is not required. Instead, the interpretation was performed by framing around more manipulable risk factors, such as environmental and health care facility variables. For detailed discussion on explaining “race effect,” the readers are referred to the work of VanderWeele and Robinson.32

3.4 ∣. The R package mma

The mma package, available on the Comprehensive R Archive Network (CRAN),16 was generated based on the above two algorithms for mediation analysis. It has two sets of functions for multiple mediation analysis. One is the step-by-step process, where the function data.org helps identify the mediators/confounders and covariates, and then, the organized data sets are read into the function med to estimate the mediation/confounding effects (IE, TE, DE). Finally, the function boot.med helps to report summary statistics of the estimated mediation/confounding effects, where the standard deviations and confidence intervals are calculated using the bootstrap method. An alternative process combines the three steps in one function, mma. For both sets of functions, linear or nonlinear predictive models can be chosen for mediation analysis. By default, generalized linear models or Cox proportional hazard models are used to model the associations among variables, depending on the type of response variable. If the nonlinear method is chosen, MART and smoothing splines are used to model the relationships.

The mma package provides generic functions to help explain the results from mediation analysis. For our research, any variable that is significantly related with race and is significantly associated with the outcome when other covariates are included in the Cox hazard model is treated as a potential mediator/confounder. Variables that significantly associate with the outcome when other variables are adjusted, but not significantly related with the race are included in the mediation analysis as other covariates. Variables that are not related with the outcome when other variables are considered are excluded for further analysis. The function data.org tests associations among variables and identify mediator/confounders and covariates. Its results can be summarized to show selected variables and the tests (p-values) for each associations of interests. Moreover, the outputs from the function boot.med or mma can be summarized to show the inference results on mediation/confounding effects (estimates, standard deviations, and confidence intervals). The graphic function, plot, helps researchers visualize the complicated relationships and explain the racial differences in breast cancer survival. The readers are referred to the work of Yu and Li16 for details on how to use the mma package and to the work of Yu et al17 for examples of applying the mma package.

4 ∣. RESULTS

We explore the racial disparity in breast cancer survival using the mediation analysis with multiple mediators/confounders15 on Louisiana cancer patients diagnosed in 2004. The outcome is the right-censored number of days after diagnosis with breast cancer (censor = 1 if the patient died and 0 if the number of days is for last follow-up).

4.1 ∣. Selection of potential mediators/confounders

Potential mediators/confounders are the variables that may explain the racial disparity. By literature review and variable availability, we tested all variables in Table 1 (except for race and outcome) to identify potential mediators/confounders and covariates.

To identify mediators/confounders, we test the significance of two associations: 1) between race and each potential mediator/confounder; and 2) between each potential mediator/confounder and the survival outcome, when other variables are controlled.2 For these tests, we set the significance level at 0.1. To test the first association, we use ANOVA for continuous potential mediators/confounders and Chi-square test for categorical mediators/confounders. For the second association, we use the type-III tests in a Cox proportional hazard model with all potential variables. Tables 2 and 3 show some summary statistics, test results, and the identified mediators/confounders (*) and covariates (−). In addition, variables that are theoretically considered as critical in explaining the racial disparity can be forced into the analysis as mediators without statistical tests. We forced in three groups of related variables as mediators/confounders: 1) the health care facility variables: bed size, hospital ownership, teaching status, and COC status; 2) census tract socio economic factors: poverty, education, and employment; and 3) cancer stage related variables: stage, lymph nodes involvement, extension, and tumor size. Within each group, the variables are highly correlated. We are more interested in the joint effects from each group than from each individual variable. Forced-in mediators/confounders are denoted by + in Tables 2 and 3.

TABLE 2.

Potential categorical mediators/confounders and covariates

| Potential Mediators/Confounders | Black | White | P-value 1 | P-value2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| insurance*: no insurance | 33.00% | 13.06% | < .0001 | < .0001 |

| public insurance | 29.95% | 9.28% | ||

| private insurance | 62.32% | 87.51% | ||

| marital status: single | 33.00% | 13.06% | < .0001 | .752 |

| married | 38.30% | 59.18% | ||

| separated or divorced | 9.62% | 7.41% | ||

| widowed | 19.07% | 20.35% | ||

| comorbidity: no/mild | 36.08% | 49.00% | < .001 | .657 |

| moderate | 48.93% | 39.55% | ||

| severe | 14.99% | 9.92% | ||

| tumor grade*: I | 9.23% | 17.20% | < .001 | .086 |

| II | 37.64% | 47.63% | ||

| III | 49.82% | 32.61% | ||

| IV | 3.32% | 2.57% | ||

| lateral: left | 49.76% | 52.52% | .3173 | .122 |

| lymph nodes involvement+: yes | 55.61% | 62.09% | .0156 | .125 |

| extension+:yes | 89.43% | 93.40% | .008 | .227 |

| cancer subtype*: ErPr−, Her2− | 23.85% | 12.25% | < .001 | < .001 |

| ErPr+, Her2− | 39.58% | 50.25% | ||

| ErPr−, Her2+ | 12.19% | 9.72% | ||

| ErPr+, Her2+ | 24.38% | 27.78% | ||

| stage+: 1. Localized | 50.41% | 58.50% | < .001 | .127 |

| 2. Regional by direct extension only | 1.78% | 1.85% | ||

| 3. Ipsilateral regional lymph node(s) only | 31.60% | 27.86% | ||

| 4. Regional by both 2 and 3 | 5.19% | 5.20% | ||

| 7. Distant sites | 11.02% | 6.59% | ||

| poverty+: ≥ 20% | 71.13% | 26.80% | < .001 | .440 |

| education+: ≥ 25% | 71.77% | 39.06% | < .001 | .184 |

| residence area: rural | 62.58% | 46.16% | < .001 | .328 |

| mixed | 6.29% | 13.52% | ||

| urban | 31.13% | 40.32% | ||

| employment+: ≥ 66% | 81.29% | 53.61% | < .001 | .865 |

| surgery*: no | 9.24% | 4.05% | < .001 | < .001 |

| lumpectomy | 45.06% | 46.99% | ||

| mastectomy | 45.71% | 48.96% | ||

| radiation: no | 56.04% | 53.38% | .335 | .183 |

| chemo-therapy*: no | 54.81% | 68.83% | < .001 | .027 |

| hormonal*: no | 60.86% | 48.89% | < .001 | .002 |

| hospital ownership+: private | 77.2% | 74.42% | .259 | .206 |

| teaching hospital+: yes | 53.54% | 39.27% | < .001 | .491 |

| COC status+: yes | 64.35% | 64.66% | .948 | .703 |

Note: See footnotes of Table 3.

TABLE 3.

Potential continuous mediators/confounders and covariates

| Potential Mediators | Black Mean (SD) |

White Mean (SD) |

P-value 1 | P-value 2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| age at diagnosis* | 57.95(14.08) | 61.47(13.65) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| BMI* | 32.52(8.06) | 29.24(7.08) | <.0001 | .012 |

| tumor size* | 30.15(26.48) | 22.73(18.68) | <.0001 | <.0001 |

| bed size+ | 3.40(1.43) | 3.31(1.38) | .229 | .117 |

Note: P-value 1 shows the p-value of testing the association between race and the row variables. P-value 2 is the p-value of Type III test for the row variable in the full cox model in predicting the hazard rate.

indicates the variable is chosen as a mediator/confounder, − a covariate, + a forced-in mediator/confounder.

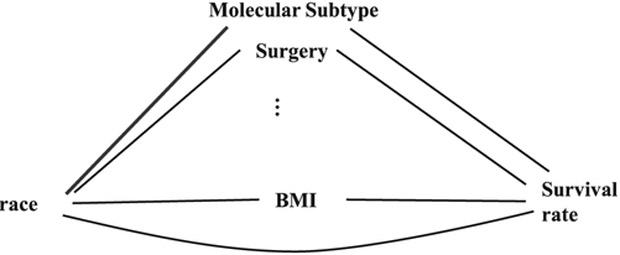

From Tables 2 and 3, we found that variables marital status, comorbidity, lateral, residence area, and radiation were not significantly related with the risk of death when other variables were adjusted and thus were excluded for further analysis. Variables in groups were forced into the analysis, where their joint effects would be estimated. Accounting for the selected potential mediators/confounders, no variables were selected as covariates. A conceptual model is shown by Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The conceptual model to explore the racial disparity in breast cancer survival

4.2 ∣. Mediation/confounding effects explaining the racial disparity in breast cancer survival

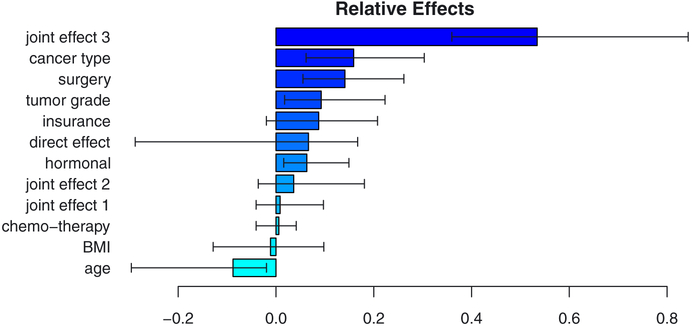

Table 4 shows the estimated direct and indirect effects in explaining the racial disparity in breast cancer survival for Louisiana patients who were diagnosed with breast cancer in 2004 using the linear (Cox proportional hazard model and generalized linear model) and nonlinear (MART survival model and smoothing splines) models, respectively. “RE” denotes the relative effect, which is defined as the corresponding direct or indirect effect divided by the total effect. In the Tables, joint effect 1 is the joint effect from the health care facility variables, joint effect 2 from the census tract socio economic factors, and joint effect 3 from the cancer stage related variables. For both models, the racial disparity in the breast cancer survival was completely explained by all included variables as indicated that the direct effect was not significantly different from 0. Figure 2 shows the estimated relative effects and their confidence intervals based on MART.

TABLE 4.

Summary of mediation/confounding effect estimations for breast cancer survival

| Mediator/confounder | Linear Models | Nonlinear Models | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IE (95% CI) | RE (%) | IE (95% CI) | RE (%) | |

| joint effect 3 | 0.276 (0.109, 0.528) | 43.9 (7.3, 162.7) | 0.275 (0.185, 0.556) | 53.4 (36.0, 84.3) |

| molecular subtype | 0.264 (0.153, 0.690) | 41.9 (14.2, 161.9) | 0.082 (0.038, 0.179) | 15.9 (6.2, 30.3) |

| surgery | 0.016 (−0.063, 0.088) | 2.6 (−14.2, 22.4) | 0.073 (0.031, 0.179) | 14.1 (5.5, 26.2) |

| tumor grade | 0.135 (−0.012, 2.203) | 21.5 (−2.9, 107.5) | 0.048 (0.011, 0.034) | 9.2 (1.8, 22.3) |

| age at diagnosis | −0.166 (−0.271, −0.043) | −26.4 (−87.6, −2.6) | −0.045 (−0.171, −0.014) | −8.8 (−29.6, −1.9) |

| insurance | 0.151 (−0.001, 0.325) | 23.9 (−2.3, 80.6) | 0.045 (−0.01, 0.136) | 8.7 (−1.9, 20.8) |

| hormonal | 0.131 (−0.012, 0.335) | 20.9 (−2.5, 120.3) | 0.033 (0.009, 0.095) | 6.3 (1.6, 14.9) |

| joint effect 2 | 0.075 (−0.228, 0.379) | 11.9 (−36.7, 162.7) | 0.019 (−0.020, 0.124) | 3.6 (−3.6, 18.1) |

| joint effect 1 | −0.034 (−0.165, 0.118) | −5.5 (−43.0, 14.2) | 0.004 (−0.025, 0.074) | 0.9 (−4.1, 9.7) |

| chemo-therapy | −0.087 (−0.266, 0.015) | −13.8 (−66.2, 2.8) | 0.003 (−0.024, 0.025) | −0.6 (−4.1, 4.1) |

| bmi | −0.084(−0.298, 0.266) | −13.4(−92.5, 23.4) | −0.006 (−0.069, 0.061) | −1.1 (−12.8, 9.8) |

| direct effect | −0.058 (−0.732, 0.563) | −9.3 (−355.0, 66.1) | 0.034 (−0.163, 0.133) | 6.6 (−28.8, 16.7) |

| total effect | 0.629 (0.135, 2.815) | 0.515 (0.392, 0.971) | ||

Note: The mediators/confounders are ordered according to the absolute value of the estimated relative effect (RE) with nonlinear models. The variables with significant indirect effects (IE) are boldfaced. jointeffect 1 is the joint effect from the health care facility variables, joint effect 2 from the census tract social economics factors, and joint effect 3 from the cancer stage related variables.

FIGURE 2.

Relative effects from nonlinear models [Colour figure can be viewed at wileyonlinelibrary.com]

Compared with whites, non-Hispanic blacks have an average higher hazard rate by both linear (TE = 0.629, 95% CI (0.135, 2.815)) and nonlinear (TE = 0.515, 95% CI (0.392, 0.971)) models. That is, on average, the instantaneous death at any time is 67.36%(e0.034 – 1) higher among blacks than among whites by nonlinear models. From Table 4, we see that the confidence intervals for estimated (in)direct effects are much wider using linear models than using nonlinear models. This is due to the inclusion of many highly correlated variables in predicting the hazard rate. The multi-collinearity results in highly variant estimates from linear models. MART accounts for potential nonlinear relationship in hazard prediction and is much more robust to multi-collinearities. To explain the results, we focus on the nonlinear models. Table 4 orders the mediators/confounders according to the absolute value of their estimated relative effects from MART.

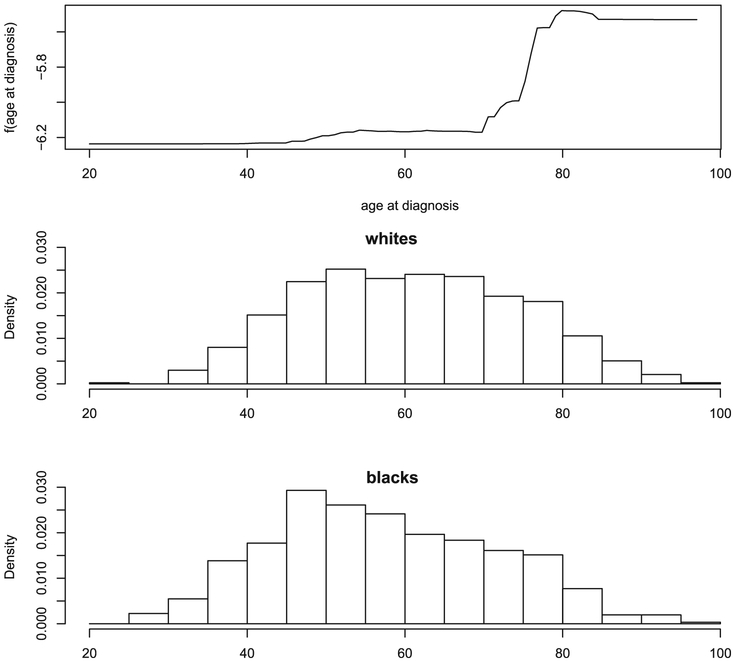

“Direct effect” is the racial disparity that cannot be explained by all the mediators/confounders included in the model. In Table 4 we found that the estimated 95% confidence interval of direct effect is (−0.163, 0.133), which includes 0. The cancer stage related variables (stage, tumor size, lymph nodes involvement, extension, and tumor size), joint effect 3, explained about 53.4% of the racial disparity in survival. Other variables such as molecular subtype (15.9%), surgery (14.1%), tumor grade (9.2%), and hormonal therapy (6.3%) also significantly explain the racial difference. An interesting variable is age at diagnosis, which have a negative indirect effect (opposite to the total effect) and a significant negative relative effect (−8.8%). This can be explained by Figure 3: the hazard rate decreases with age at diagnosis (upper panel of Figure 3), and blacks tended to be diagnosed at younger ages than whites. The middle and lower panels of Figure 3 show the age distributions among whites and blacks respectively. Therefore, accounting for age would enlarge the gap in hazard rates between blacks and whites.

FIGURE 3.

Indirect effect of age on breast cancer hazard

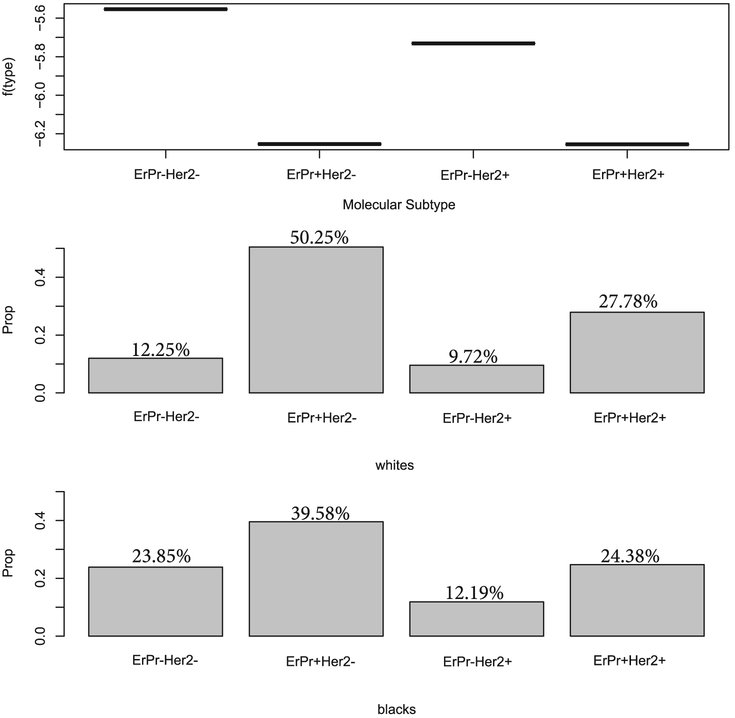

The mma R package provides visual aids to understand the relationships among variables. For example, Figure 3 describes how age mediated the racial disparity in cancer survival. Similarly, Figure 4 describes how tumor size can explain the racial disparity in survival. The top plot shows the relationship between tumor size and the hazard rate. The line was fitted using the Multiple Additive Regression Trees (MART). We can see that the hazard increases as the tumor size increases. The lower two plots shows the tumor size distributions among whites (middle plot) and blacks (lower plot) population. We found that whites were diagnosed with cancer at a relatively smaller tumor size than were blacks. Combined with other cancer stage related variables, more than half (53.4%) of the racial disparity was explained. Figure 5 shows how the categorical variable molecular subtype helps explain the racial disparity in cancer survival. On average, ER or PR negative has an average higher hazard rate than ER/PR positive patients, and there are more blacks that were diagnosed with ER/PR negative (36.04% in blacks vs 21.97% in whites). Therefore, molecular subtype explained 15.9% of the racial disparity. The supplementary material provides the graphs for all mediators/confounders that explore how each of them explains the racial disparity in anxiety score.We did not find significant joint effect from the census tract level social economics factors. Overall, diagnosed at an early age, at early stages, with ER/PR positive, had surgery, with low tumor grade, and had hormonal therapy are related with high survival rate.

FIGURE 4.

Indirect effect of tumor size on breast cancer hazard

FIGURE 5.

Indirect effect of cancer type on breast cancer hazard

5 ∣. SIMULATIONS

We conducted two simulations to check the performance of the proposed multiple mediation analysis method on time-to-event outcomes. The first simulation is to check the results when the predictor is continuous and when the mediators are highly correlated. The second simulation considers the situation when a relationship is not linear. The R codes to generate the simulation data sets and conduct analysis are provided in the supplementary material.

5.1 ∣. Simulation 1

In this simulation, the predictor X is continuous, following a uniform distribution between −1 and 1. We generate 500 observations independently. There are two continuous mediators, M1 and M2, which were generated such that

where i = 1, …, 500 and (ϵ1i, ϵ2i)T has a bivariate-normal distribution with mean (0, 0)T, variance (1, 1)T, and the correlation coefficient between ϵ1i and ϵ2i is ρ which were set at (0, 0.3, 0.6, 0.9) separately to indicate independent to highly correlated relationship between M1 and M2 after adjusting for X. We assume the true underlying model is the Cox-proportional hazards model where the survival time distribution is exponential with an average survival time at the baseline to be 500 days. We also have that f(xi, M1i, M2i) in the formula (2) be 1.402xi + 0.283M1i + 2.15M2i. The survival times were then generated according.33 The starting day, the day a patient enters the trial, is generated as uniform between 1 and 500, and the censoring day is set at the 600th day. That is, the response variable is yi = (ti, δi), where ti = min(starttimei + survivaltimei, 600) and δi is 1 if starttimei + survivaltimei < 600 and 0 otherwise. Using the linear method, we check how the associate between M1 and M2 can influence the inference on mediation effects. We repeat the simulation 100 times. Table 5 shows the average biases and ranges of the confidence intervals (CIs) from the 100 repetitions for the estimated mediation effects when ρ is set at (0, 0.3, 0.6, 0.9) separately. All the analyses were done with the R package mma, and the number of repetitions for the bootstrap process is 100 times. Both mediators were forced in to be considered as potential mediators.

TABLE 5.

Average biases and ranges of confidence intervals of the estimated mediation effects

| ρ | Average Bias | Average Range of CI | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DE | IE1 | IE2 | DE | IE1 | IE2 | |

| 0 | −0.0071 | −0.0005 | −0.0269 | 0.5473 | 0.1557 | 0.7397 |

| 0.3 | −0.0036 | −0.0031 | −0.0348 | 0.5394 | 0.1606 | 0.7317 |

| 0.6 | −0.0134 | −0.0027 | −0.0414 | 0.5347 | 0.1819 | 0.7466 |

| 0.9 | −0.0156 | −0.0027 | −0.0422 | 0.5381 | 0.3058 | 0.8099 |

By the setting, the true direct effect of X is 1.402, indirect effect for M1 is 0.1466, and for M2, it is 1.5072. We found that when the correlation coefficient between M1 and M2 increases, there is not consistent change in biases for estimating all the mediation effects. Moreover, the biases are generally controlled to be less than 3% of the true value. As for the range of 95% CIs, there is no consistent change in estimating the direct effect. When the correlation between M1 and M2 increases, the range of the CIs for indirect effects for both M1 and M2 increases but not at a significant level. We conclude that for this case, the proposed mediation analysis method can efficiently separate indirect effects from correlated mediators even when they are highly correlated and when linear models are used.

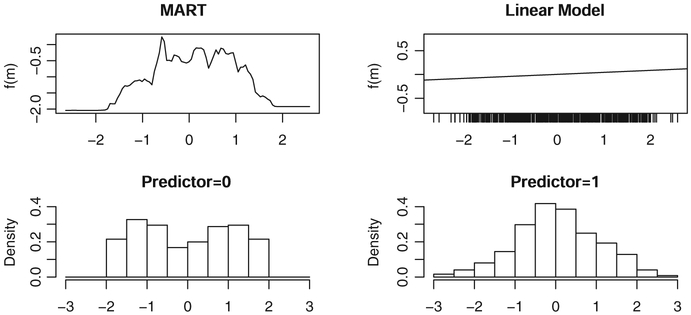

5.2 ∣. Simulation 2

The setting for the second simulation is about the same as that for Simulation 1 except that the exposure variable is binary and there is only one mediator. The exposure variable follows a Bernoulli distribution with the probability of success 0.5. When X = 0, the mediator M follows a uniform distribution between −2 and 2. When X = 1, the mediator M follows a standard normal distribution. To simulate Y, we have f(xi,Mi) = 1.402xi − 0.518M2, and everything else is the same as in Simulation 1. M is forced in the analysis as a potential mediator. Using the linear model and MART to fit f, respectively, the estimated mediation effects and their confidence intervals are shown in Table 6.

TABLE 6.

Summary of mediation effect estimations for Simulation 2

| Effects | Linear Model | MART | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| IE (95% CI) | RE (%) | IE (95% CI) | RE (%) | |

| Direct Effect | 1.355 (1.085, 1.633) | 99.9 (98.8 101.2) | 1.223 (0.946, 1.611) | 85.8 (74.9, 94.9) |

| Mediator (M) | 0.003 (−0.014, 0.016) | 0.2 (−1.0, 1.2) | 0.214 (0.70, 0.388) | 15.0 (5.1, 25.3, −10) |

| Total Effect | 1.357 (1.086, 1.640) | 1.425 (1.154, 1.858) | ||

We found that using the linear model, the indirect effect from M is not detectable, while MART is more powerful in identifying mediation effects when there is nonlinear relationship. Figure 6 explains the reason and the direction of indirect effect through the mediator. The upper panel shows how f changes with M by different models: the left figure was fitted by MART, and the right figure by the linear model. MART roughly catches the quadratic marginal relationship between f and M. f increases with M until around 0 and then decreases with M. That is, f achieves the highest value when M is around 0. The lower panel of Figure 6 shows the distributions of M at the two different populations (X = 0 on the left and X = 1 on the right). We found that, compared with X = 0 group, there were a higher proportion of observations having an M around 0 when X is 1. Therefore, M can explain part of the relationship between X and Y. Since the linear model cannot catch the quadratic relationship between f and M without any transformation of the variables, using linear model does not help in identifying M as a mediator for this case.

FIGURE 6.

Indirect effect of M on the predictor-outcome relationship

6 ∣. CONCLUSIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

Mediation analysis is used most often in health sciences and psychological research, with different behavioral and sociodemographic variables used as the mediators/confounders. Its application in a study such as this one is to identify which factors could be important in explaining the relationship between a predictor and an outcome from a large pool of candidate mediators/confounders. In this paper, we extend the general mediation analysis to the survival context that can deal with time-censored outcomes. Using the method, we explored the racial disparity in survival among breast cancer patients in Louisiana using the PoC special study. The PoC study was linked with other data sources such as cancer registry database and census data. The comprehensive set of variables were used and completely explained the racial disparity in breast cancer survival. We found that using the nonlinear hazard models, eg, MART, can better explain the racial disparity since it accounts for nonlinear relationship and it is more robust to outliers and multi-collinear relationships.

It is clear that the specific findings with regard to the racial disparity in survival in Louisiana will not be generalizable to the whole United States. While the generalizability of specific findings is a limitation, it does not limit the overall aim of identifying the drivers of the racial disparity. Findings in this regard will still have important implications for guiding the development of future interventions and policy.

As future research, we will extend the method to multilevel mediation analysis within the survival context. Therefore, we can separate the mediation/confounding effects from different levels of variable resources (eg, individual or neighborhood level). In addition, to include information and knowledge in mediation analysis, we will use the mediation analysis method in Bayesian setting.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This study was partially funded by the NIH/NIMHD award number 1R15MD012387 and by the Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center Pilot Fund.

Funding information

National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities, Grant/Award Number: 1R15MD012387

Footnotes

SUPPORTING INFORMATION

Additional supporting information may be found online in the Supporting Information section at the end of the article.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lynch JW, Kaplan GA, Cohen RD, Tuomilehto J, Salonen JT. Do cardiovascular risk factors explain the relation between socioeconomic status, risk of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and acute myocardial infraction. Am J Epidemiol. 1996;144:934–942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1986;51(6):1173–1182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alwin DF, Hauser RM. The decomposition of effects in path analysis. Am Sociol Rev. 1975;40(37):37–47. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Judd CM, Kenny DA. Process analysis: estimating mediation in treatment evaluations. Eval Rev. 1981;5(5):602–619. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mackinnon DP, Dwyer JH. Estimating mediated effects in prevention studies. Eval Rev. 1993;17(2):144–158. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Robins JM, Greenland S. Identifiability and exchangeability for direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology. 1992;3:143–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Have TRT, Joffe MM, Lynch KG, Brown GK, Maisto SA, Beck AT. Causal mediation analyses with rank preserving models. Biometrics. 2007;63:926–934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Albert JM. Mediation analysis via potential outcomes models. Statist Med. 2008;27:1282–1304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.VanderWeele TJ. Marginal structural models for the estimation of direct and indirect effects. Epidemiology. 2009;20:18–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.VanderWeele TJ, Vansteelandt S. Conceptual issues concerning mediation, interventions, and composition. Stat Its Interface. 2009;2:457–468. [Google Scholar]

- 11.VanderWeele T, Vansteelandt S. Mediation Analysis with Multiple Mediators. Epidemiol Methods. 2014;2:95–115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Imai K, Keele L, Yamamoto T. Identification, inference, and sensitivity analysis for causal mediation effects. Stat Sci. 2010;25:51–71. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Imai K, Yamamoto T. Identification and sensitivity analysis for multiple causal mechanisms: revisiting evidence from framing experiments. Political Anal. 2013;21:141–171. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Steen J, Loeys T, Moerkerke B, Vansteelandt S. Flexible mediation analysis with multiple mediators. Am J Epidemiol. 2017;186:184–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yu Q, Fan Y, Wu X. General multiple mediation analysis with an application to explore racial disparities in breast cancer survival. J Biom Biostat. 2014;5:189. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yu Q, Li B. An R package for mediation with multiple mediators. J Open Res Softw. 2017;5(1):11. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yu Q, Scribner RA, Leonardi C, et al. Exploring racial disparity in obesity: a mediation analysis considering geo-coded environmental factors. Spatial Spatio-temporal Epidemiol. 2017;21:13–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hsieh M. Multiple Mediation Analysis with Survival Data [dissertation]. New Orleans, LA: Tulane University; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang YT, Yang HI. Causal mediation analysis of survival outcome with multiple mediators. Epidemiology. 2017;28:370–378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vandenberghe S, Duchateau L, Slaets L, Bogaerts J, Vansteelandt S. Surrogate marker analysis in cancer clinical trials through time-to-event mediation techniques. Stat Methods Med Res. 2017. 10.1177/0962280217702179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenberg J, Chia YL, Plevritis S. The effect of age, race, tumor size, tumor grade, and disease stage on invasive ductal breast cancer survival in the U.S. SEER database. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;89:47–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sassi F, Luft HS, Guadagnoli E. Reducing racial/ethnic disparities in female breast cancer: screening rates and stage at diagnosis. Am J Public Health. 2006;96:2165–2172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gerend MA, Pai M. Social determinants of black-white disparities in breast cancer mortality: a review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2008;17:2913–2923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warner ET, Tamimi RM, Hughes ME, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in breast cancer survival: mediating effect of tumor characteristics and sociodemographic and treatment factors. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33:2254–2261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bain RP, Greenberg RS, Whitaker JP. Racial differences in survival of women with breast cancer. J Chronic Dis. 1986;39:631–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Eley J, William. Racial differences in survival from breast cancer. J Am Med Assoc (JAMA). 1994;272:947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lu Y, Ma H, Malone KE, et al. Obesity and survival among black women and white women 35 to 64 years of age at diagnosis with invasive breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3358–3365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dignam JJ. Efficacy of systemic adjuvant therapy for breast cancer in African-American and Caucasian women. J Natl Cancer Inst (JNCI) Monographs. 2001;2001:36–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tian N, Goovaerts P, Zhan FB, Chow TE, Wilson JG. Identifying risk factors for disparities in breast cancer mortality among African-American and Hispanic women. Women′s Health Issues. 2012;22:e267–e276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.MacKinnon DP, Krull JL, Lockwood CM. Equivalence of the mediation confounding and suppression effect. Prev Sci. 2000;1:173–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fan Y. Multiple Mediation Analysis with General Predictive Models [dissertation]. New Orleans, LA: Louisiana State University Health Sciences Center; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 32.VanderWeele TJ, Robinson WR. On the causal interpretation of race in regressions adjusting for confounding and mediating variables. Epidemiology. 2014;25:473–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bender R, Augustin T, Blettner M. Generating survival times to simulate Cox proportional hazards models. Statist Med. 2005;24:1713–1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.