Abstract

Native top-down mass spectrometry (MS) and ion mobility spectrometry were applied to characterize the interaction of a molecular tweezer assembly modulator, CLR01, with tau, a protein believed to be involved in a number of neurodegenerative disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease. The tweezer CLR01 has been shown to inhibit aggregation of amyloidogenic polypeptides without toxic side effects. ESI-MS spectra for different forms of tau protein (full-length, fragments, phosphorylated, etc) in the presence of CLR01 indicate a primary binding stoichiometry of 1:1. The relatively high charging of the protein measured from nondenaturing solutions is typical of intrinsically disordered proteins, such as tau. Top-down mass spectrometry using electron capture dissociation (ECD) is a tool to determine not only the sites of post-translational modifications, but also the binding site(s) of non-covalent interacting ligands to biomolecules. The intact protein and the protein-modulator complex were further subjected to ECD-MS to obtain sequence information, map phosphorylation sites, and pinpoint the sites of inhibitor binding. ESI-MS data for intact tau proteins indicate that top-down MS is amenable to the study of various tau isoforms and their post-translational modifications (PTMs). The ECD-MS data point to a CLR01 binding site in the microtubule-binding region of tau, spanning residues K294-K331, which includes a six-residue nucleating segment PHF6 (VQIVYK) implicated in aggregation. Furthermore, ion mobility experiments on the tau fragment reveal a shift towards a more compact structure in the presence of CLR01. The mass spectrometry study suggests a picture for the molecular mechanism for the modulation of protein-protein interactions in tau by CLR01.

INTRODUCTION

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a complex neurodegenerative disorder that manifests itself through loss of synaptic transmission and neuronal death. Most neurodegenerative diseases are defined by a single type of lesion. By contrast, the complex pathophysiology in AD includes a double proteinopathy characterized by aggregation of amyloid β-protein (Αβ) in amyloid plaques and hyperphosphorylated tau protein in neurofibrillary tangles (NFT) [1, 2]. Though insoluble NFTs are the hallmark of tau pathology, early-forming, water-soluble tau oligomers are likely the most toxic species [3–5]. Interest in tau pathophysiology is not limited to AD but extends to other diseases collectively known as tauopathies, in which aberrant post-translational modification and self-assembly of tau into neurotoxic species is a central underlying mechanism [6, 7].

Tau stabilizes microtubules and is expressed predominantly in the central and peripheral nervous systems with an abundant presence in axons. It consists of an N-terminal projection domain, a proline-rich region, a microtubule-binding repeat region, and a C-terminal domain. In human brain, alternative mRNA splicing of microtubule associated protein tau (MAPT) transcripts on chromosome 17q21.31 results in 6 isoforms of the tau protein ranging from 352 to 441 amino acids in length [8, 9]. These isoforms differ depending on the number of 29-residue inserts and can be categorized depending on whether they contain three or four carboxy-terminal repeat domains (3R or 4R, respectively).

Tau is a natively unfolded or intrinsically disordered protein (IDP). However, this does not altogether eliminate global order. Single-molecule Forster resonance energy transfer (FRET) has shown long-range N-and C-termini contacts, as well as contacts between both termini and repeat regions, resulting in an S-shaped fold [10]. Full-length tau assembles into filaments via its repeats, with the N- and C-terminal regions forming a fuzzy coat [11, 12]. Recombinant tau filaments, as well as those derived from the human brain contain a cross-β structure core of ~90 amino acids, characteristic of amyloid fibrils [13]. This core includes the microtubule-binding region (MTBR) region. Two important nucleating sequences within the MTBR have been identified, namely PHF6 (VQIVYK) and PHF6* (VQIINK) [14].

In the brain, tau undergoes various post-translational modifications (PTMs) including phosphorylation, acetylation, methylation, glycosylation, isomerization, O-GlcNAcylation, nitration, sumoylation, ubiquitination, as well as truncation [7]. Several PTMs have been considered to play a key role in tau aggregation [15]. Among these, phosphorylation is the major modification with 85 putative sites located on tau. Abnormal phosphorylation (at nonphysiological sites) is a key characteristic of NFTs and in AD; it is thought to precede tau aggregation [16]. Tau phosphorylation is inversely related to its ability to bind microtubules and filamentous tau is abnormally phosphorylated [17]. But whether phosphorylation is a cause or a byproduct of aggregation remains to be determined. To date, there is no strong evidence linking changes in kinase or phosphatase activity to human tauopathies. Although aggregated tau is heavily phosphorylated in the human brain, not all phosphorylated tau is aggregated. In fact, there is evidence to suggest that highly phosphorylated tau is associated with neuroplasticity, a reversible process that is not associated with the formation of filaments [18]. There is recent evidence linking full-length tau hyperphosphorylation to conformational shifts and amyloidogenic propensity.

Non-covalent interactions between molecules possessing aromatic rings (π-π and CH-π) are generally acknowledged to be important in the formation of ordered biological systems [19–21]. Therefore, a host molecule that is designed to exploit aromatic interactions for targeted recognition of certain amino acids in relevant peptide regions could be of significant therapeutic interest. The approach of applying synthetic compounds known as molecular tweezers (MT) to inhibit abnormal self-assembly of proteins via combination of hydrophobic and electrostatic interactions has been shown to be effective against amyloidogenic proteins [22, 23]. The name “molecular tweezer” was first used in the 1990s to describe a class of U-shaped molecules with rigid aromatic side walls. The U-shaped cavity, in principle, could accommodate a sterically favorable functional group on a target molecule [24].

Contrary to the many artificial receptor molecules that have been developed for amino acids with little to no selectivity to specific residues, the MT compound CLR01 shows selectivity towards lysine, and to lesser extent arginine residues. CLR01 binds preferentially with high on-off rate to Lys residues on unstructured proteins and remodels their assembly into non-toxic, non- amyloidogenic structures. It acts as a unique nanochaperone, which rather than assisting in the folding of the native structure, prevents formation of toxic oligomers and aggregates. A derivative compound, CLR03, that shares the polar bridgehead structure but lacks the hydrophobic arms, was designed as a negative control [25]. The mechanism of MT inhibition is based on competing electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions, which are essential for abnormal self-assembly and aggregation. Furthermore, low binding affinity and high on-off rate allow MT to disrupt abnormal self-assembly without interfering with normal protein function [22, 23].

ESI-MS and IMS for structural analysis of tau and tau/CLROl complex

Since the early 1990s, electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) has been used for the measurement of noncovalent protein-protein and protein-ligand complexes [26–28]. Through its soft ionization process, “native” ESI [29] generally does not result in molecular fragmentation and can preserve weakly-bound complexes and ligands, from salts and solvent molecules to metal cofactors and protein aggregates. While lacking the direct three-dimensional structural information provided by X-ray crystallography and NMR, ESI-MS can nevertheless provide valuable stoichiometry and heterogeneity information. Thus, ESI-MS can reveal a specific picture of the protein quaternary structure [30].

Contrary to the more commonly employed “bottom-up” approach, whereby proteins are enzymatically digested followed by tandem spectrometry, “top-down” MS has the potential to retain labile PTMs and ligands generally lost in the bottom-up approach [31–35]. Moreover, tandem MS/MS using electron capture dissociation (ECD) can better preserve labile PTMs often lost during collisionally-activated dissociation [36].

Native top-down MS can also reveal the specific site(s) of noncovalent ligand binding and the location of surface residues [31, 37–41]. ECD fragmentation dissociates covalent backbone bonds but preserves non-covalently bound ligands. We have effectively implemented ECD-MS to study the interaction of various aggregation-prone proteins with molecular tweezer CLR01. Our top-down ESI-ECD-MS/MS approach was used to identify the binding sites of CLR01 on Αβ protein [42] and α-synuclein (AS), the aggregation-prone pathogenic species in Parkinson’s disease [43]. Most recently, using native ESI-MS for the analysis of the 17-residue N-terminal fragment (N17) of Huntingtin protein (Htt), implicated in the pathology of Huntington’s disease, we observed a 1:1 N17:CRL01 complex with an estimated Kd of 20 μΜ. In addition, ECD-MS/MS revealed Lys9 as the most probable site of CLR01 binding to N17 [44].

In this study, we employed native top-down ESI-MS and ion mobility MS to gain structural insight into tau and the tau/CLR0l complex. We sought to determine tau/CLR0l binding stoichiometry and well as map site(s) of CLR01 binding. Because phosphorylation is implicated in tau’s propensity to aggregate, we analyzed phosphorylated tau and its CLR01 binding properties.

EXPERIMENTAL

Materials.

The expression of 0N3R, PHP-0N3R, and some of the 2N4R tau used for this study from the Center for Medical Biotechnology, University of Duisburg-Essen was published previously [42]. Some 2N4R tau, 4R fragment, the C291A fragment, and its phosphorylated form were from Unite de Glycobiologie Structurale et Fonctionnelle, CNRS, Universite Lille; the expression and purification protocols are detailed in the Supplemental Materials. The proteins stored in 10 mM HEPES, 50 mM (NH4)2, 2 mM TCEP, pH 7.5 were buffer exchanged into 200 mM ammonium acetate, pH 6.8. Tau/CLR0l complexes were prepared at 1:1, 1:2 and 1:5 ratios, respectively. CLR01 and CLR03 were prepared and purified as described previously [45].

Mass spectrometry.

Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance (FT-ICR) MS experiments were performed using a 15-Tesla Bruker SolariX system with an infinity ICR cell. Protein solutions were loaded into metal-coated borosilicate capillaries (Au/Pd-coated, l-μm i.d.; Thermo Fisher Scientific, West Palm Beach, FL, USA) and sprayed at a flow rate of 10–40 nL/min through a nanoESI source. The ESI capillary voltage was set to 0.9 kV. The time-of-flight was 1 ms. ECD experiments were performed on isolated precursor ions (10 m/z isolation window) with an ECD pulse length of 0.03 s, ECD bias of 1.5 V, and ECD lens of 10 V. Up to 400 scans were averaged for each spectrum, and all spectra were externally calibrated with cesium iodide. MS/MS spectra were initially interpreted with the aid of ProSight Light (Northwestern University), in-house software, and verified manually using Protein Prospector (v 5.20.0; University of California, San Francisco).

Ion mobility spectrometry.

Ion mobility (IM) experiments were performed on a Waters Synapt G2-Si quadrupole time-of-flight (QTOF) system equipped with a travelling wave ion mobility separation (TWIMS) module. All ion mobility spectra were acquired in positive-ion mode. Capillary voltage and cone voltage were set to 1.2 kV and 30 V, respectively. Up to 300 scans were averaged for each acquisition.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Top-down MS of tau and tau/CLR01 complex

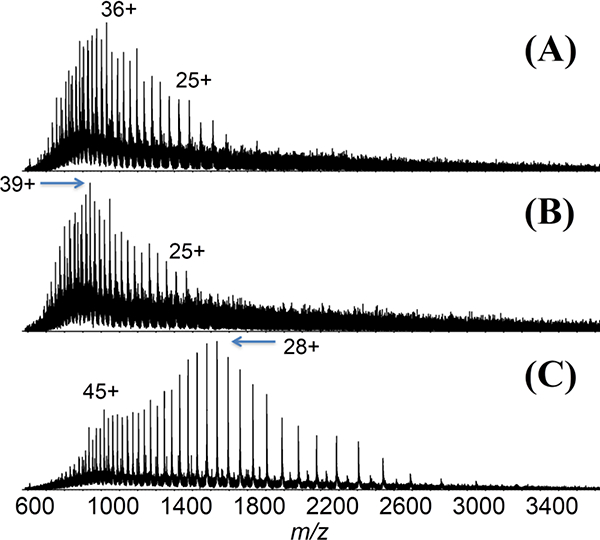

ESI-MS spectra for intact tau proteins acquired in aqueous pH 6.8 solutions show a high degree of charging (Figure 1). The intrinsically disordered nature of the protein appears to enable a high degree of charging that is more typical of globular proteins measured from denaturing solution conditions [46].

Figure 1.

ESI mass spectra of (A) pseudohyperphosphoryalted PHP-3R-tau (37.1 kDa), (B) 3R-tau (36.8 kDa), and (C) 4R-tau (45.8 kDa) from pH-6.8 aqueous solutions.

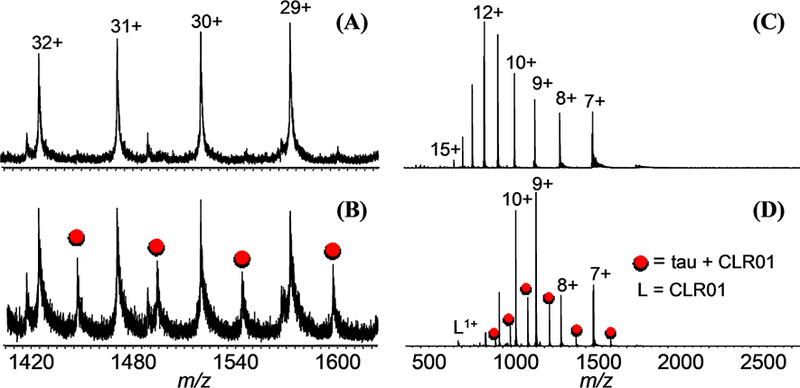

A 4R-tau and a 4R-repeat fragment (residues 257–359; 11 kDa) were examined for binding to CLR01 (sequences listed in Figure S1). Previously, using thioflavin-T fluorescence and electron microscopy, CLR01 was shown to inhibit 0N3R-tau aggregation (induced by arachidonic acid) completely at 1:1 molar ratio [42]. The addition of CLR01 (structure; see Figure S2) to the tau proteins resulted in non-covalently bound 1:1 protein/CLR01 complexes, which appear as distinct distributions with characteristic shifts to higher m/z values for each charge state (Figure 2). A relatively low fraction of the tau proteins were found to bind to CLR01, which is consistent to the micromolar-range Kd binding constants found for CLR01 binding to other proteins examined previously [43]. The 4R-fragment tau spectra show a bimodal charge state distribution that is not observed in the CLR01-bound distribution (Figure 2D). This may be an indication that CLR01 binding stabilizes tau by shifting it towards a single conformation (vide infra).

Figure 2.

(A) ESI-MS of 4R tau, (B) CLR01 + 4R tau, (C) 4R-repeat domain fragment, and (D) CLR01 + 4R-repeat domain fragment. (Red circles represent peaks for the 1:1 protein/ CLR01 complex).

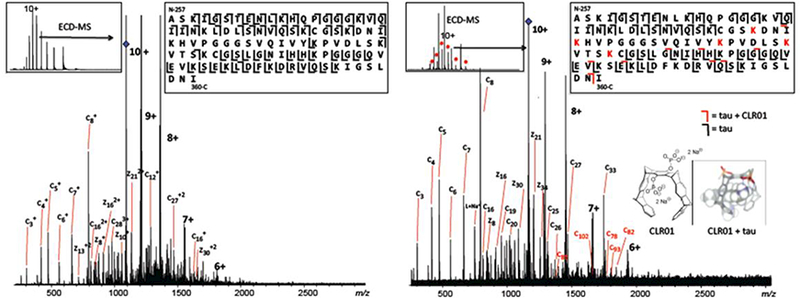

The intact 4R-fragment tau and 4R-fragment tau/CLR0l complex were further subjected to native top-down MS with ECD to obtain sequence information and pinpoint the site(s) of inhibitor binding (Figure 3). For the 10+ charge state of the intact 4R-fragment tau, both N- and C-termini showed extensive fragmentation, but formation of ECD product ions from the core region spanning the microtubule-binding domain was poor in comparison (Figure 3 left panel). This could be due to the presence of a disulfide bond, as there are two Cys-residues in this core region. But despite the limited fragmentation in the microtubule-binding region, up to six fragments were observed between the two cysteines, suggesting that the disulfide bond only shielded part of this region.

Figure 3.

ECD-MS of 10+ charge state of 4R-repeat domain fragment. Fragmentation pattern in the control (left) vs ligand-bound state (right), indicate CLR01 binding in the MTBR region, spanning lysines K294-K331.

Top-down ECD-MS of the 10+-charged holo-form showed CLR01-bound c- and z-product ions (Figure 3 right panel, marked in red) that point towards the core of the tau fragment as the likely region of ligand binding. This is the part of the microtubule-binding domain that contains the 6- residue nucleating segment PHF6 (VQIVYK) that forms a characteristic cross-β steric zipper. From the molecular tweezer CLR0l’s bias towards binding to lysine residues, the top-down mass spectra suggests CLR01 to be bound to the K294-K331 region, which includes lysine K294, K298, K311, K317, K321, and K331, and is a known microtubule-binding region. This is consistent with solution-state NMR studies on tau and CLR01 binding, which show the greatest perturbation in the NMR spectra at resonances for K321 and K331 (data not shown).

Because CLR01 binding has been shown to disrupt tau oligomerization, and the VQIVYK segment has been shown as a key component of the seeding process for fibrilization, it may be reasonable to infer that CLR0l’s inhibitory effect is related to its binding to lysines at or near the VQIVYK region, i.e., K290, K311, K317, K321, K331.

This interpretation of the data presented in Figure 3 is further supported by the ECD-MS fragmentation pattern of the 4R-repeat domain fragment C291A (Figure S3), where a cysteine substitution to alanine eliminated the possibility of the disulfide bond and resulted in considerable fragmentation in that region. Fragmentation patterns of the CLR01-bound 17+ charge state point to CLR01 binding to lysines spanning the VQIINK and VQIVYK regions (lysines K294, K298, K311, K317, K321) (Figure S4), similar to the proposed binding sites for the 10+ charge state of the 4R-tau fragment (Figure 3). Certainly, CLR01 binds to many Lys residues. The fragmentation map (Figure S4) shows evidence for CLR01 binding to other Lys residues outside the proposed binding region (microtubule-binding domain), but their relative abundance compared to product ions containing lysine residues in the proposed binding region is lower. The fact that CLR01 binds to a microtubule-binding domain that is prone to aggregation is a significant result of this study.

Overall, the tau protein sequences have an unusually stable core region that appears to be stable to ECD dissociation. Fragmentation appears to be limited to the flexible termini regions (Figure 3). Other intrinsically disordered proteins, such as α-synuclein, allow for much higher yields for top-down MS, up to 90% sequence coverage [47]. The data shown for the 103-residue 4R-repeat domain fragment shows 61% sequence coverage (62 interresidue cleavages out of 102 total interresidue bonds) for the apo-form. The 4R-repeat domain C291A fragment (Figures S3, S4, S5) is 30% longer (133-residues). But besides being a longer sequence, it is unclear why sequence coverage is significantly lower (less than 40%) compared to the data shown in Figure 3. Sequence coverage is difficult to predict, as many factors are likely to contribute to top-down MS efficiency. However, the native top-down MS data is consistent with the subsequent IM-MS data that shows the compaction of the protein upon CLR01 binding (vide infra). Sequence coverage drops from 61% to 46% with CLR01 binding.

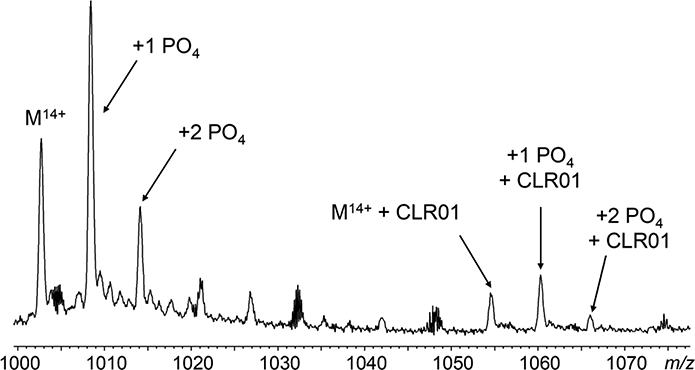

Because tau phosphorylation is directly related to its ability to bind microtubules, we tested our native top-down MS methods to map phosphorylation sites on a synthetic phosphorylated 4R-tau fragment C291A. CLR01 binding to phosphorylated tau was also tested. In the case of tau, it is particularly interesting to determine how phosphorylation affects the action of the negatively charged CLR01. ESI-MS shows singly- and doubly-phosphorylated 4R-tau fragment C291A, and a 1:1 complex formed between both singly- and doubly-phosphorylated 4R-fragment C291A and CLR01 (Figure 4). ECD-MS of the singly-phosphorylated protein established the primary phosphorylation site to be S235 (Figure S5), one of several serine/threonine sites found in endogenous forms of tau to be phosphorylated. T231 is another site expected to be phosphorylated. From the holo-c234 product ion, the fragmentation map suggests T231 to be phosphorylated also. However, the holo-c237 product is 7 times more abundant than holo-c234, suggesting that T231 is a secondary phosphorylation site to S235. (Unfortunately, the signal intensity of the doubly-phosphorylated and CLR01-bound C291A 4R-fragment tau were not sufficient for isolation and fragmentation by ECD-MS with our instrument system.)

Figure 4.

Partial ESI mass spectrum of phosphorylated 4R-repeat domain fragment C291A showing multiple phosphorylation events in the unmodified and CLR01-bound forms (tau/CLR0l, 1:1)

Ion mobility MS of tau and tau/CLR01

In a 2015 publication, the Bowers group reported the use of ion mobility coupled to mass spectrometry (IM-MS) to study the effect of CLR01 binding to Αβ [48]. IM-MS can separate gas phase protein aggregates and protein-ligand complexes based on their size and shape. Ions of different sizes and shapes will experience different mobilities and drift times as they travel through a chamber filled with an inert gas under a low electric field [48–50]. Ion drift time is a direct consequence of its size and shape, or collisional cross-section (CCS). Folded or more compact species will therefore experience shorter drift times. This feature enables the separation of conformers having the same m/z, oligomers, proteins with various PTMs, and proteins bound to ligands. The Bowers study revealed a CLR01-mediated compaction of Αβ dimers and tetramers, eliminating higher-order oligomers [48]. Their work prompted us to apply IM-MS to investigate the effects of CLR01 binding on the structure of tau.

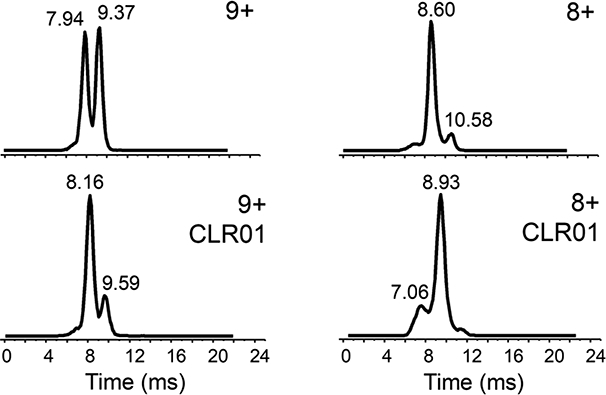

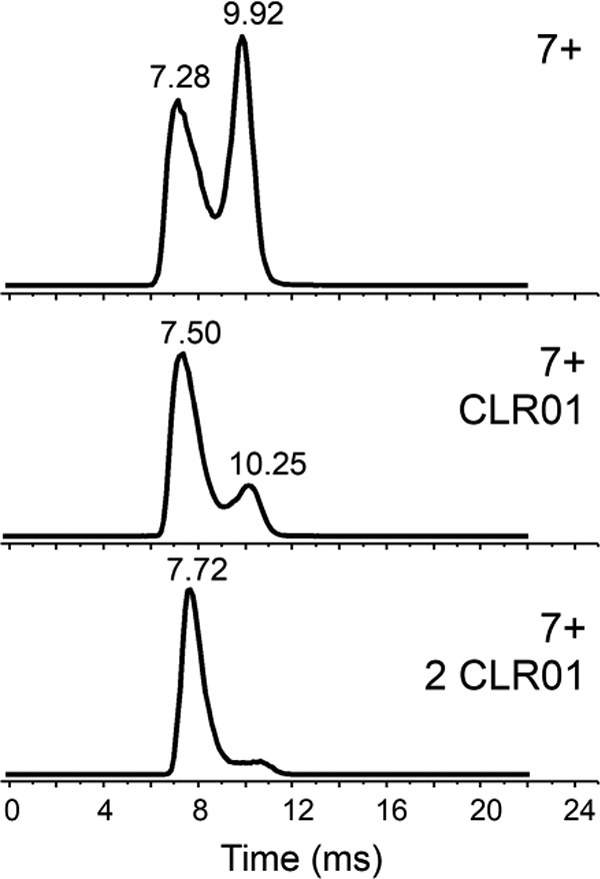

Ion mobility spectra of 4R-tau fragment were acquired under native solution conditions. There were significant differences in ion mobility profiles between the free and CLR01-bound 4R-tau fragment for the 9+ and 8+ charge states (Figure 5). A shift towards a more compact form and a decrease in the elongated form is promoted upon CLR01 binding. This is more readily observed for the 7+ charged protein (Figure 6). The more elongated conformer represented by the peak with a drift time of ca. 10 ms deceased in relative abundance with an increase in the more compact conformer (drift time ca. 7.5 ms) upon CLR01 binding. A small amount of a doubly- CLR01 bound form is also present; this effect towards a more compact form is even more pronounced for this doubly-bound form (data not shown). A similar relationship between tau compaction and charge state was also observed for the singly CLR0l-bound C291A 4R-tau fragment, especially for the lower charge states (Figure S6). The TWIMS resolving power for these tau proteins is similar to our TWIMS measurements of another intrinsically disordered protein, α-synuclein [47, 51] and a recent TWIMS study of tau proteins [52].

Figure 5.

IM-MS of 9+ (left) and 8+ (right) charge states of 4R-repeat domain fragment with and without CLR01 (40 μΜ tau/CLR0l in a 1:1 ratio).

Figure 6.

IM-MS of 7+ charge states of unbound 4R-repeat domain tau fragment (top), singly-bound (middle) and doubly-bound fragment (bottom) with CLR01 (40 μΜ tau/CLR0l in a 1:1 ratio).

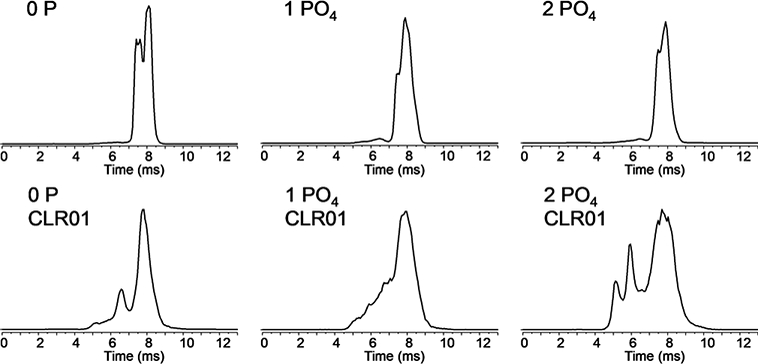

Similar shifts towards more compact structures were also observed for the phosphorylated C291A 4R-tau fragment. Singly- and doubly-phosphorylated species showed little to no difference in drift time compared to the unmodified version. The binding of CLR01 resulted in the appearance of more compact structures. For example, for the 13+ charge state, there were marked differences in overall peak shape and drift time between the unmodified and doubly- phosphorylated tau in the presence of CLR01 (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

IM-MS of 13+ charge state of zero-, mono-and di-phosphorylated 4R-tau C291A fragment with and without CLR01 bound. (1:1 protein:ligand complex).

It is not completely clear what influence phosphorylation has on phosphoprotein gas phase structures. From work reported by Scrivens [53] and Clemmer [54], phosphorylation of peptides results in compaction of peptide conformations from intramolecular interactions with neighboring residues and the peptide backbone. Whether this behavior extends to larger phosphoprotein systems is unclear. Ion pairing, e.g., salt bridges, could indeed affect gas phase structures [55]. The data shown in Figure 7 for singly- and doubly-phosphorylated tau does not indicate a significant difference in gas phase structure with phosphorylation. But CLR01-binding drives protein compaction for the phosphorylated proteins even more so compared to the non-phosphorylated versions.

Overall, the IM-MS analysis of the 4R-tau fragment showed that CLR01 binding reduces or eliminates longer drift-time species, suggesting that CLR01 binding shifts tau fragment conformation towards a more compact structure. This structural remodeling may point to a mechanism of CLR01-mediated inhibition of aggregation.

CONCLUSIONS

Data from native MS cast CLR01-mediated inhibition of tau aggregation in a more structurally informative light, with some insight into the mechanism of inhibition. ECD-MS data point towards the microtubule-binding domain as the likely site of CLR01 binding, which agrees with CLR01 stabilization of tau function. The microtubule-binding region also spans the two six-residue nucleating segments PHF6 (VQIVYK) and PHF6* (VQIINK) shown to be essential for seeding. It seems likely that the disruption of aggregation would involve CLR01 binding at or near these residues. From a mechanistic point of view, it also appears that inhibition of tau aggregation via CLR01 occurs through some form of structural remodeling and compaction of the protein. Similar results were obtained with Αβ and CLR01, where direct remodeling of Αβ by CLR01 disrupted the formation of dimers and tetramers, preventing higher-order oligomers from forming [48]. Future experiments will aim to identify how sequence alternations in various tau isoforms and tau PTMs affect CLR01 binding. These findings once again highlight the unique features of assembly modulator CLR01 and its tremendous therapeutic potential.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Dr. Hong Nguyen (UCLA) for help with data processing and Dr. Jing Di (UCLA) for providing the tau samples and sample information. A.B. and M.E. were supported by CRC1093 from Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft. Support from the US National Institutes of Health (R01GM103479, S10RR028893, S10OD018504 to J.A.L.; RF1AG054000, R01AG050721 to G.B.), the Development and Promotion of Science and Technology Talents Project (DPST) and Royal Thai Government (to P.W.), the Rachadapisek Sompot Fund, Chulalongkorn University (to P.W.), and the US Department of Energy (DE-FC02–02ER63421) are gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Brion JP, Flament-Durand J, Dustin P: Alzheimer’s disease and tau proteins. Lancet 328, 1098 (1986) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Drubin DG, Kirschner MW: Tau protein function in living cells. J. Cell Biol 103, 2739–2746 (1986) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goedert M, Spillantini MG: Pathogenesis of the tauopathies. J. Mol. Neurosci 45, 425–431 (2011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kirkitadze MD, Bitan G, Teplow DB: Paradigm shifts in Alzheimer’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders: The emerging role of oligomeric assemblies. J. Neurosci. Res 69, 567–577 (2002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klein WL, Krafft GA, Finch CE: Targeting small Αβ oligomers: The solution to an Alzheimer’s disease conundrum? Tr. Neurosci 24, 219–224 (2001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Martin L, Latypova X, Terro F: Post-translational modifications of tau protein: Implications for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurochem. Int 58, 458–471 (2011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Spillantini MG, Goedert M: Tau pathology and neurodegeneration. Lancet Neuro. 12, 609–622 (2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goedert M, Spillantini MG, Jakes R, Rutherford D, Crowther RA: Multiple isoforms of human microtubule-associated protein tau: Sequences and localization in neurofibrillary tangles of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuron 3, 519–526 (1989) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Neve RL, Harris P, Kosik KS, Kurnit DM, Donlon TA: Identification of cDNA clones for the human microtubule-associated protein tau and chromosomal localization of the genes for tau and microtubule-associated protein 2. Mol. Brain Res 1, 271–280 (1986) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Elbaum-Garfinkle S, Rhoades E: Identification of an aggregation-prone structure of tau. J. Am. Chem. Soc 134, 16607–16613 (2012) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goedert M, Wischik CM, Crowther RA, Walker JE, Klug A: Cloning and sequencing of the cDNA encoding a core protein of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease: Identification as the microtubule-associated protein tau. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85, 4051–4055 (1988) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wischik CM, Novak M, Edwards PC, Klug A, Tichelaar W, Crowther RA: Structural characterization of the core of the paired helical filament of Alzheimer disease. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 85, 4884–4888 (1988) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Berriman J, Serpell LC, Oberg KA, Fink AL, Goedert M, Crowther RA: Tau filaments from human brain and from in vitro assembly of recombinant protein show cross-β structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 9034–9038 (2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Von Bergen M, Barghorn S, Li L, Marx A, Biernat J, Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E: Mutations of tau protein in frontotemporal dementia promote aggregation of paired helical filaments by enhancing local β-structure. J. Biol. Chem 276, 48165–48174 (2001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Avila J: Tau phosphorylation and aggregation in Alzheimer’s disease pathology. FEBS Lett. 580, 2922–2927 (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mandelkow EM, Mandelkow E: Biochemistry and cell biology of tau protein in neurofibrillary degeneration. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol 3, 1–25 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iqbal K, Liu F, Gong CX: Tau and neurodegenerative disease: The story so far. Nature Rev. Neurol 12, 15–27 (2016) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arendt T, Stieler J, Strijkstra AM, Hut RA, Rudiger J, Van der Zee EA, Harkany T, Holzer M, Hartig W: Reversible paired helical filament-like phosphorylation of tau is an adaptive process associated with neuronal plasticity in hibernating animals. J. Neurosci 23, 6972–6981 (2003) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Meyer EA, Castellano RK, Diederich F: Interactions with aromatic rings in chemical and biological recognition. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 42, 1210–1250 (2003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Salonen LM, Ellermann M, Diederich F: Aromatic rings in chemical and biological recognition: Energetics and structures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 50, 4808–4842 (2011) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Schneider HJ: Interactions in supramolecular complexes involving arenes: Experimental studies. Acct. Chem. Res 46, 1010–1019 (2013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Attar A, Bitan G: Disrupting self-assembly and toxicity of amyloidogenic protein oligomers by “molecular tweezers”- from the test tube to animal models. Curr. Pharm. Des 20, 2469–2483 (2013) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Attar A, Chan WTC, Klarner FG, Schrader T, Bitan G: Safety and pharmacological characterization of the molecular tweezer CLR01 - a broad-spectrum inhibitor of amyloid proteins’ toxicity. BMC Pharm. Toxicol 15, 23 (2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Klarner FG, Benkhoff J, Boese R, Burkert U, Kamieth M, Naatz U: Molecular tweezers as synthetic receptors in host-guest chemistry: Inclusion of cyclohexane and self-assembly of aliphatic side chains. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 35, 1130–1133 (1996) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schrader T, Bitan G, Klarner F-G: Molecular tweezers for lysine and arginine - powerful inhibitors of pathologic protein aggregation. Chem. Commun 52, 11318–11334 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loo JA: Bioanalytical mass spectrometry: Many flavors to choose. Bioconj. Chem 6, 644–665 (1995) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Loo JA: Studying noncovalent protein complexes by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. Mass Spectrom. Rev 16, 1–23 (1997) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith RD, Light-Wahl KJ: The observation of non-covalent interactions in solution by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry: Promise, pitfalls and prognosis. Biol. Mass Spectrom 22, 493–501 (1993) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leney AC, Heck AJR: Native mass spectrometry: What is in the name? J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 28, 5–13 (2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chait BT, Cadene M, Olinares PD, Rout MP, Shi Y: Revealing higher order protein structure using mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 28, 952–965 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xie Y, Zhang J, Yin S, Loo JA: Top-down ESI-ECD-FT-ICR mass spectrometry localizes noncovalent protein-ligand binding sites. J. Am. Chem. Soc 128, 14432–14433 (2006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ge Y, Lawhorn BG, ElNaggar M, Strauss E, Park JH, Begley TP, McLafferty FW: Top down characterization of larger proteins (45 kDa) by electron capture dissociation mass spectrometry. J. Am. Chem. Soc 124, 672–678 (2002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yin S, Xie Y, Loo JA: Mass spectrometry of protein-ligand complexes: Enhanced gas-phase stability of ribonuclease-nucleotide complexes. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 19, 1199–1208 (2008) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riley NM, Mullen C, Weisbrod CR, Sharma S, Senko MW, Zabrouskov V, Westphall MS, Syka JEP, Coon JJ: Enhanced dissociation of intact proteins with high capacity electron transfer dissociation. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 27, 520–531 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Li H, Wongkongkathep P, Van Orden SL, Ogorzalek Loo RR, Loo JA: Revealing ligand binding sites and quantifying subunit variants of noncovalent protein complexes in a single native top-down FTICR MS experiment. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 25, 2060–2068 (2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen B, Guo X, Tucholski T, Lin Z, McIlwain S, Ge Y: The impact of phosphorylation on electron capture dissociation of proteins: A top-down perspective. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 28, 1805–1814 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li H, Nguyen HH, Ogorzalek-Loo RR, Campuzano IDG, Loo JA: An integrated native mass spectrometry and top-down proteomics method that connects sequence to structure and function of macromolecular complexes. Nature Chem. 10, 139–148 (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yin S, Loo JA: Top-down mass spectrometry of supercharged native protein-ligand complexes. Int. J. Mass Spectrom 300, 118–122 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang H, Cui W, Wen J, Blankenship RE, Gross ML: Native electrospray and electron-capture dissociation in FTICR mass spectrometry provide top-down sequencing of a protein component in an intact protein assembly. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 21, 1966–1968(2010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang H, Cui W, Wen J, Blankenship RE, Gross ML: Native electrospray and electron-capture dissociation FTICR mass spectrometry for top-down studies of protein assemblies. Anal. Chem 83, 5598–5606 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang J, Ogorzalek Loo RR, Loo JA: Structural characterization of a thrombin- aptamer complex by high resolution native top-down mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 28, 1815–1822 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sinha S, Lopes DHJ, Du Z, Pang ES, Shanmugam A, Lomakin A, Talbiersky P, Tennstaedt A, McDaniel K, Bakshi R, Kuo PY, Ehrmann M, Benedek GB, Loo JA, Klarner FG, Schrader T, Wang C, Bitan G: Lysine-specific molecular tweezers are broad-spectrum inhibitors of assembly and toxicity of amyloid proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc 133, 16958–16969 (2011) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Acharya S, Safaie BM, Wongkongkathep P, Ivanova MI, Attar A, Klärner FG, Schrader T, Loo JA, Bitan G, Lapidus LJ: Molecular basis for preventing α-synuclein aggregation by a molecular tweezer. J. Biol. Chem 289, 10727–10737 (2014) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Vopel T, Bravo-Rodriguez K, Mittal S, Vachharajani S, Gnutt D, Sharma A, Steinhof A, Fatoba O, Ellrichmann G, Nshanian M, Heid C, Loo JA, Klarner FG, Schrader T, Bitan G, Wanker EE, Ebbinghaus S, Sanchez-Garcia E: Inhibition of huntingtin exon-1 aggregation by the molecular tweezer CLR01. J. Am. Chem. Soc 139, 5640–5643 (2017) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Talbiersky P, Bastkowski F, Klarner FG, Schrader T: Molecular clip and tweezer introduce new mechanisms of enzyme inhibition. J. Am. Chem. Soc 130, 9824–9828 (2008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Natalello A, Santambrogio C, Grandori R: Are charge-state distributions a reliable tool describing molecular ensembles of intrinsically disordered proteins by native MS? J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 28, 21–28 (2017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wongkongkathep P, Han JY, Choi TS, Yin S, Kim HI, Loo JA: Native top- down mass spectrometry and ion mobility MS for characterizing the cobalt and manganese metal binding of α-synuclein protein. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 29, in press (2018) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zheng X, Liu D, Klarner FG, Schrader T, Bitan G, Bowers MT: Amyloid β- protein assembly: The effect of molecular tweezers CLR01 and CLR03. J. Phys. Chem. B 119, 4831–4841 (2015) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaddis CS, Lomeli SH, Yin S, Berhane B, Apostol MI, Kickhoefer VA, Rome LH, Loo JA: Sizing large proteins and protein complexes by electrospray ionization mass spectrometry and ion mobility. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 18, 1206–1216 (2007) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kaddis CS, Loo JA: Native protein MS and ion mobility: Large flying proteins with ESI. Anal. Chem 79, 1778–1784 (2007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Choi TS, Lee J, Han JY, Jung BC, Wongkongkathep P, Loo JA, Lee MJ, Kim HI: Supramolecular modulation of structural polymorphism in pathogenic α-synuclein fibrils using copper(II) coordination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed 57, 3099–3103 (2018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jebarupa B, Muralidharan M, Srinivasu BY, Mandal AK, Mitra G: Effect of altered solution conditions on tau conformational dynamics: Plausible implication on order propensity and aggregation. BBA - Proteins and Proteomics 1866, 668–679 (2018) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thalassinos K, Grabenauer M, Slade SE, Hilton GR, Bowers MT, Scrivens JH: Characterization of phosphorylated peptides using traveling wave-based and drift cell ion mobility mass spectrometry. Anal. Chem 81, 248–254 (2009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Glover MS, Dilger JM, Acton MD, Arnold RJ, Radivojac P, Clemmer DE: Examining the influence of phosphorylation on peptide ion structure by ion mobility spectrometry-mass spectrometry. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 27, 786–794 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ogorzalek Loo RR, Loo JA: Salt bridge rearrangement (SaBRe) explains the dissociation behavior of noncovalent complexes. J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom 27, 975–990 (2016) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.