Abstract

Introduction

Durability is a key requirement for the broad acceptance of bariatric surgery. We report on durability at and beyond 10 years with a systematic review and meta-analysis of all reports providing data at 10 or more years and a single-centre study of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) with 20 years of follow-up.

Methods

Systematic review with meta-analysis was performed on all eligble reports containing 10 or more years of follow-up data on weight loss after bariatric surgery. In addition, a prospective cohort study of LAGB patients measuring weight loss and reoperation at up to 20 years is presented.

Results

Systematic review identified 57 datasets of which 33 were eligible for meta-analysis. Weighted means of the percentage of excess weight loss (%EWL) were calculated for all papers included in the systematic review. Eighteen reports of gastric bypass showed a weighted mean of 56.7%EWL, 17 reports of LAGB showed 45.9%EWL, 9 reports of biliopancreatic bypass +/− duodenal switch showed 74.1%EWL and 2 reports of sleeve gastrectomy showed 58.3%EWL. Meta-analyses of eligible studies demonstrated comparable results. Reoperations were common in all groups. At a single centre, 8378 LAGB patients were followed for up to 20 years with an overall follow-up rate of 54%. No surgical deaths occurred. Weight loss at 20 years (N = 35) was 30.1 kg, 48.9%EWL and 22.2% total weight loss (%TWL). Reoperation rate was initially high but reduced markedly with improved band and surgical and aftercare techniques.

Conclusion

All current procedures are associated with substantial and durable weight loss. More long-term data are needed for one-anastomosis gastric bypass and sleeve gastrectomy. Reoperation is likely to remain common across all procedures.

Keywords: Weight loss, Bariatric surgery, Long term, Meta-analysis, 20-year follow-up, Reoperation rates

Introduction

The durability of weight loss is the key difference between medical weight loss programs and bariatric surgery [1, 2]. Many medical weight loss programs have reported substantial weight loss but almost none have reported durability beyond 2 years. The Look AHEAD study [3] has been an exception where, with major effort and high costs, a modest effect of 6% total weight loss was reported at a median follow-up of 9.6 years.

Most publications of outcomes after bariatric surgery cover the short term (1–3 years). Some cover the medium term (3–10 years) and just a few provide data on long-term weight loss (10 or more years). Effectiveness and durability are considered key attributes of bariatric surgery when compared with the non-surgical approaches to achieving weight loss. For bariatric surgery to claim a key role in obesity care, strong proof of effectiveness in the long term is needed.

In 2013, we published a systematic review of weight loss at 10 or more years after bariatric surgery, in particular, Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), biliopancreatic diversion with or without duodenal switch (BPD/DS) and laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB), and we included 15-year outcome data from our patient group after LAGB [4]. That report included 23 datasets from 20 reports available in November 2011. Since that time, the number of published reports providing long-term follow-up data has more than doubled, with 57 datasets now available including some long-term data on sleeve gastrectomy. In addition, we provide very long-term follow-up (20-year) data on our experience with LAGB. To date, only two reports of very long-term data after bariatric surgery are available [5, 6]. We report the systematic review and our own data on 1 January 2018.

Materials and Methods

Systematic Review of the Literature

The present report is a synthesis of two systematic reviews. The first search was of the medical literature up to November 2011 and has been published [4]. For the present report, the literature search was extended to December 31, 2017. The pooled data are reported according to the latest Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [7].

Search Strategy

Articles were identified using the Cochrane Database, Embase, Medline Complete, PubMed, and Scopus electronic databases with the last electronic search conducted on December 31, 2017. Only published full reports were included. Search terms were developed across concepts of “bariatric surgery” ‘AND’ “longitudinal/long term/10 year”. In addition, reference lists of included articles were examined, as were three relevant systematic reviews [8–10]. Hand searching of Obesity Surgery and Surgery for Obesity and Related Disorders was also performed.

Eligibility Criteria

Original peer-reviewed English language papers were considered for inclusion. The review considered all types of bariatric surgical procedures except for short-term temporary procedures or experimental procedures (e.g. intragastric balloon, endoscopic duodeno-jejunal bypass sleeve, intragastric stimulation). For inclusion, papers must have reported the weight loss data of at least 10 patients at ≥ 10 years after the initial surgery and expressed the weight outcome as percentage of excess weight loss (%EWL) or percentage of BMI lost (%BMIL) or had provided sufficient information to allow these values to be calculated. Although there has been a recent drive to express weight loss as % total weight loss, almost no data were available in this format. For eligible papers, the data at the final time point that met the inclusion criteria pertaining to participant numbers and weight outcome measurement are reported. We also sought to extract from eligible papers data on operation type, number of patients originally treated and the number at longest eligible follow-up, percentage patients lost to follow up, reoperation rates and weight loss outcome at maximum follow-up. Not all these data are available within the selected papers.

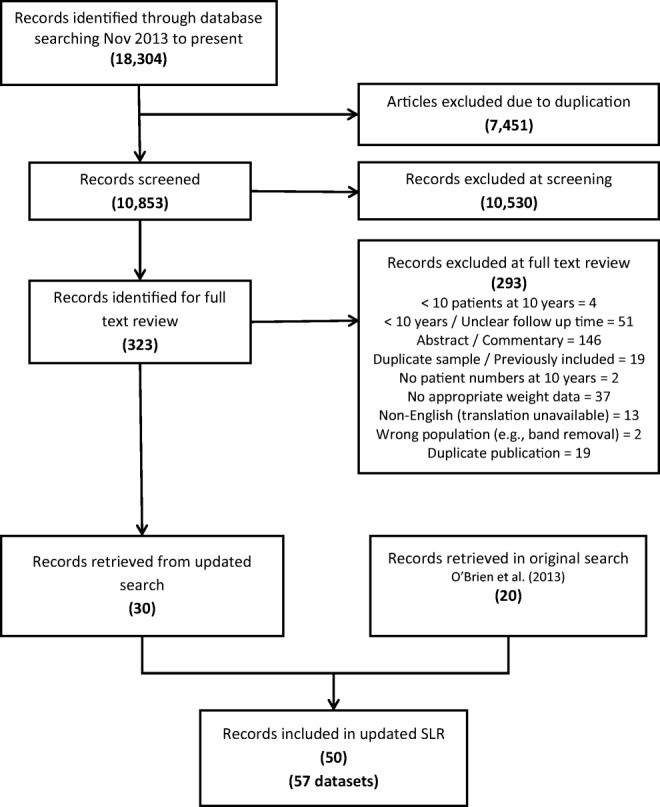

One reviewer conducted title and abstract screening with 10% cross-checked by a second reviewer. Both reviewers examined articles identified for full-text review and disagreements concerning inclusion were resolved by joint review. Figure 1 displays the PRISMA search process for the current review with the original review studies added.

Fig. 1.

The flow diagram of the systematic review. The eligible articles from the earlier systematic review [4] are added at the level of included studies

Longitudinal Cohort Study

We have conducted a prospective longitudinal cohort study of all patients having LAGB as a primary bariatric procedure through the Centre for Bariatric Surgery (CBS) in Melbourne from 1994 to the present. The LAP-BAND™ (Apollo Endosurgery, Austin, TX, USA) was used in all cases. The methods of the study are detailed in the earlier report [4]. Briefly, patients treated by LAGB were entered into an electronic medical record for bariatric surgery (LapBase; LapBase Pty Ltd., Melbourne, Australia) at the initial visit. At each visit, the weight was entered. The program provided calculated values for various weight-related parameters (weight loss in kg, BMI change, % total weight loss (% TWL), % excess weight lost (% EWL)) longitudinally and as group reports. Follow-up compliance and group reports for attendance were also provided. Lost to follow up was defined as an absence from the clinic for more than 24 months. In contrast to the 15-year study [4], we did not actively seek contact with those who had not attended to achieve more complete follow-up.

Other clinical data such as reoperation/revision procedures, clinical consultation details, operation reports, endoscopy procedures, barium meals, letters and other reports were stored in LapBase as text or individual items but were not available as group reports. Thus, the details regarding reoperations are the results of hand searching of operation files and have been done for the patients of one surgeon (POB) only.

The outcome measures that are the focus of this report include the weight loss expressed as kg lost, change in BMI, % TWL and %EWL, and reoperation/revisional surgery details. No self-reported weights are included. %EWL was defined as the loss of excess weight in kg above a BMI of 25 kg/m2 expressed as a percentage of initial weight.

Data Analysis

For the systematic review, data for all studies identified in the original and updated searches are presented. The long-term weight loss data for individual studies are summarised in the tables. In addition, weighted means were calculated to examine the long-term %EWL across each surgery technique. As %EWL was calculated from a base of BMI of 25, reports using %EBMIL were treated as equivalent to %EWL.

For studies that reported data eligible for meta-analysis, random-effects analysis was used to calculated pooled mean effect sizes with 95% confidence intervals for each operation type; LAGB (k = 13), bypass (k = 9), biliopancreatic diversion (k = 7) and gastroplasty (k = 4). Eighteen studies were excluded from the meta-analysis as they did not report a measure of variance and 2 were single reports of a procedure only. The presence of heterogeneity among effect sizes was assessed using the Q statistic and magnitude of heterogeneity with I2. Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s regression symmetry. Comprehensive meta-analysis software (version 3) was used for all analyses.

In the 20-year longitudinal study patient data for weight loss (kg), change in BMI and %EWL were summarised using descriptive statistics and expressed as means ± 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Percentage total weight loss (% TWL) is also presented.

Results

Systematic Review

The flow diagram for the search is shown in Fig. 1. The current search covering the period November 2011 to December 2017 yielded 18,304 references. After duplicates were removed, 10,853 references were screened on title and abstract, and 323 were reviewed at full text. Additional data giving separation between the fixed gastric band and the adjustable gastric band from the Swedish Obese Subjects study [11] was provided by personal communication with Dr. Lena Carlsson. Thus, 30 reports containing 34 datasets have been added to the original review which contained 20 reports and 23 datasets to provide a total of 52 reports containing 57 separate datasets for the period 1993 to December 2017. There were two randomised controlled trials [12, 13].

All studies included in the systematic review are listed in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4 and are summarised in Table 5. There were 18 reports for gastric bypass (Table 1), 16 of which were for the Roux-en-Y (RYGB) and two were for the one anastomosis (OAGB) variant. All gastric bypass combined showed a weighted mean % EWL of 56.7% at 10 or more years with a mean of 55.4% EWL for RYGB and 80.9% EWL for OAGB. The mean EWL for the 17 reports of LAGB was 45.9% (Table 2). For the two RCTs using LAGB, the mean weight loss was 55.9% EWL. There were 11 reports of BPD ± DS which showed a mean of 74.1%EWL (table 3). For the studies of BPD (N = 4), the weighted mean was 71.5% EWL whereas for DS (N = 7), it was 75.2% EWL. Two reports of sleeve gastrectomy with a total of 79 patients (Table 4) show a mean of 57.0% EWL.

Table 1.

Gastric bypass

| Reference | Type | Initial # | FU % | Duration of FU | # pts at max. years | % EWL at max. years | % reoperation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fobi, 1993 [14] | RYGB | 100 | NR | 10 | 46 | 55 | 12 |

| Wolfel, 1994 [15] | RYGB | 143 | 71 | 10 | 83 | 49 | NR |

| Pories, 1995 [16] | RYGB | 608 | 97 | 14 | 10 | 49 | 38 |

| Sugerman, 2003 [17] | RYGB | 1025 | 37 | 10–12 | 135 | 52 | NR |

| Gunther, 2006 [5] | RYGB | 195 | 69 | 25 | 72 | 27 | 8 |

| Christou, 2006 [18] | RYGB | 274 | 84 | 12 | 161 | 68 | NR |

| Sjostrum, 2007 [19] | RYGB | 265 | NR | 15 | 10 | 66 | 17 |

| Higa, 2011 [20] | RYGB | 242 | 29 | 10 | 65 | 57 | 32 |

| Angrisani, 2013 [13] | RYGB | 24 | 84 | 10 | 21 | 69 | 29 |

| Obeid, 2016 [21] | RYGB | 328 | 46 | 10 | 134 | 59 | 64 |

| Chen, 2016 [22] | RYGB | 173 | NR | 11 | 78 | 67 | NR |

| Maciejewski, 2016 [23] | RYGB | 1787 | 82 | 10 | 564 | 56 | NR |

| Monaco-Ferreira, 2017 [24] | RYGB | 166 | 26 | 10 | 44 | 52 | NR |

| Valezi, 2013 [25] | RYGB | 211 | 55 | 10 | 116 | 65 | NR |

| Mehaffey, 2016 [26] | RYGB | 1087 | 61 | 10 | 651 | 52 | NR |

| Kothari, 2017 [27] | RYGB | 1402 | 70 | 10 | 191 | 56 | NR |

| Carbajo, 2017 [28] | SAGB | 1200 | 72 | 12 | 29 | 70 | 2 |

| Sheikh, 2017 [29] | SAGB* | 156 | 89 | 11 | 102 | 84 | 14 |

* indicates silastic ring used

Table 2.

LAGB

| Reference | Type | Initial no. | Follow-up % | Duration of FU | # pts at max. years | %EWL at max. years | % re-operations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Miller, 2007 [30] | Band | 554 | 92 | 10 | 154 | 62 | 8 |

| Favretti, 2007 [31] | Band | 1791 | 91 | 11 | 28 | 38 | 19 |

| Naef, 2010 [32] | Band | 161 | 94 | 10 | 28 | 49 | 20 |

| Himpens, 2011 [33] | Band | 154 | 54 | 12 | 36 | 48 | 60 |

| Stroh, 2011 [34] | Band | 200 | 84 | 12 | 15 | 33 | 26 |

| O’Brien, 2013a [4] | Band | 3227 | 81 | 15 | 54 | 47 | 43 |

| O’Brien, 2013b [12] | Band | 40 | 78 | 10 | 31 | 63 | 54 |

| Aarts, 2014 [35] | Band | 201 | 99 | 14 | 88 | 38 | 67 |

| Angrisani, 2013 [13] | Band | 27 | 81 | 10 | 22 | 46 | 41 |

| Arapis, 2017 [36] | Band | 897 | 90 | 15 | 348 | 42 | 56 |

| Victorzon, 2013 [37] | Band | 60 | 88 | 15 | 16 | 47 | 48 |

| Kowalewski, 2017 [38] | Band | 107 | 90 | 11 | 37 | 27 | 54 |

| Caradina, 2017 [39] | Band | 301 | 79 | 15 | 11 | 38 | 60 |

| Toolabi, 2015 [40] | Band | 80 | 23 | 13 | 18 | 47 | 78 |

| Trujillo, 2016 [41] | Band | 100 | 73 | 12 | 33 | 66 | 55 |

| Vinzens, 2017 [42] | Band | 405 | 85 | 16 | 10 | 50 | 71 |

| Sjostrom, 2007 [19] | Band | 180 | NR | 15 | 73 | 42 | 52 |

Table 3.

BPD and/or DS

| Reference | Type | Initial # | Follow-up % | Duration of FU | # pts at max. years | %EWL at max. years | Reoperation % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hess, 2005 [43] | DS | 1300 | 92 | 10 | 167 | 75 | 3.4 |

| Scopinaro, 2005 [44] | BPD | 312 | 78 | 10 | 243 | 73 | NR |

| Larrad-Jiminez, 2007 [45] | BPD | 343 | 68 | 10 | 65 | 70 | NR |

| Ballesteros-Pomar 2016 [46] | BPD | 299 | 81 | 10 | 34 | 64 | NR |

| Bolckmans, 2016 [47] | DS | 153 | 79 | 10 | 113 | 94 | 43 |

| Camerini, 2016 [48] | BPD | 120 | 65 | 15 | 79 | 67 | NR |

| Sethi, 2016 [49] | DS | 100 | 72 | 10 | 56 | 68 | 37 |

| Pata, 2013 [50] | DS | 874 | 38 | 10–15 years | 328 | 78 | 30+ |

| Topart, 2017 [51] | DS | 80 | 73 | Jan-00 | 64 | 73 | 11 |

| Marceau, 2007 [52] | DS | 1323 | NR | Jan-00 | 284 | 69 | 21+ |

| White, 2017 [53] | DS | 170 | NR | 10+ | 23 | 61 | NR |

Table 4.

Various procedures

| Reference | Procedure type | Initial # | Follow-up % | Duration of FU | # pts at max. years | %EWL at max. years | Reoperation % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arman, 2016 [54] | Sleeve | 110 | 59 | 11 | 47 | 62 | 32 |

| Felslenreich, 2016 [55] | Sleeve | 53 | 60 | 10 | 32 | 53 | 36 |

| Fobi, 1993 [14] | Gastroplasty | 100 | NR | 10 | 43 | 44 | 12 |

| Gunther, 2006 [5] | Gastroplasty | 33 | 79 | 20 | 18 | − 10 | NR |

| Sjostrom, 2007 [19] | Gastroplasty | 1369 | NR | 15 | 108 | 44 | 21 |

| Miller, 2007 [30] | Gastroplasty | 563 | 92 | 10 | 154 | 59 | 40 |

| Scozzari, 2010 [56] | Gastroplasty | 266 | 70 | 10 | 150 | 60 | 10 |

| Yu-Hung Lin, 2016 [57] | Gastroplasty | 652 | NR | 10 | 102 | 42 | 13 |

| Canetti, 2016 [58] | Gastroplasty | 51 | 71 | 10 | 36 | 50 | NR |

| Sjostrum, 2007 [19] | Fixed band | 196 | NR | 15 | 108 | 32 | 31 |

| Talebpour, 2012 [59] | Plication | 800 | NR | 10 | 35 | 42 | NR |

Table 5.

Summary of systematic review of weight loss and reoperation rates

| Procedure | No. of reports | Weighted mean % EWL | Mean % EWL range | Reoperation rate range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RYGB | 16 | 55.4 | 27–69 | 8–64% |

| OAGB | 2 | 80.9 | 70–84 | 2–14% |

| LAGB | 17 | 45.9 | 27–66 | 8–78% |

| BPD | 4 | 71.5 | 64–73 | NR |

| DS | 7 | 75.2 | 61–94 | 3–37% |

| Sleeve | 2 | 57.0 | 53–62 | 32–36% |

| Gastroplasty | 7 | 50.9 | − 10–62 | 10–40% |

The single reports of fixed band and plication from Table 6 are not included

RYGB Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, OAGB one anastomosis gastric bypass, LAGB laparoscopic adjustable gastric band, BPD biliopancreatic diversion, DS duodenal switch,, , NR = not recorded

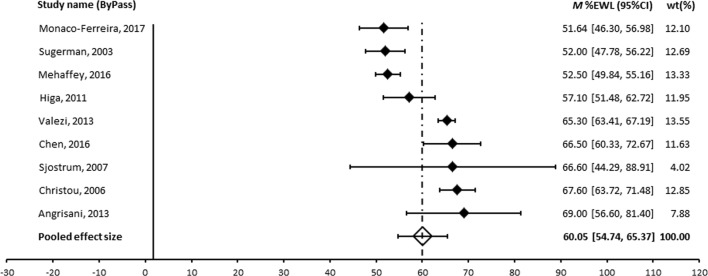

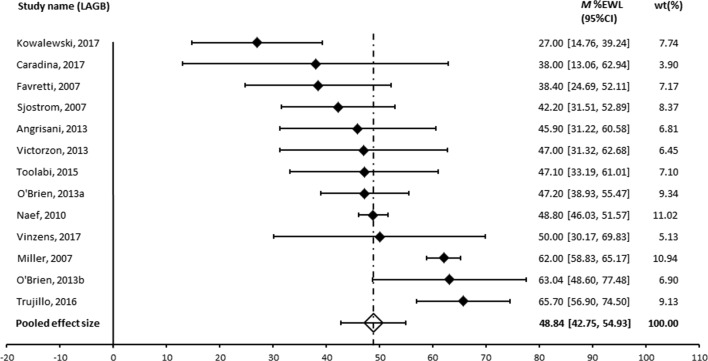

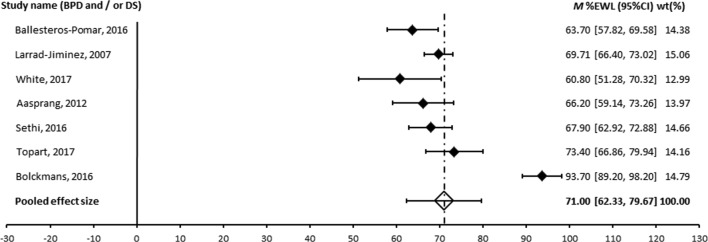

A meta-analysis was performed for those procedures where an appropriate measure of variance was provided and where more than two studies were available. The forest plots are shown in Figs. 2, 3 and 4. The pooled effect size was 60% for RYGB, 49% for LAGB and 71% for BPD ± DS. Egger’s regression was non-significant for all operation types suggesting the results are not affected by publication bias. Heterogeneity was large across all operation types [60]. Patient numbers at follow-up, assessment of heterogeneity and publication bias are shown in Table 6.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of long-term effect of RYGB on %EWL

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of long-term effect of LAGB on %EWL. The RCTs were Angrisani 2013 and O’Brien 2013b

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of BPD ± DS. The studies of Ballesteos-Pomar 2016 and Larrad-Jiminez 2007 were of BPD alone

Table 6.

Meta-analysis pooled effect sized (%EWL), heterogeneity and publication bias

| Operation | Studies (N) | Patients at follow-up | Pooled effect size (95% CI) | Q | I 2 (%) | Egger’s regression intercept |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RYGB | 9 | 1326 | 60.05 (54.74, 65.37) | 105.63* | 92.43 | − 3.33, p = .575 |

| LAGB | 13 | 485 | 48.84 (42.75, 54.93) | 80.79* | 85.15 | − 1.31, p = .262 |

| BPD/DS | 7 | 393 | 71.00 (62.33, 79.67) | 108.63* | 94.48 | − 3.33, p = .575 |

| Gastroplasty | 4 | 448 | 53.54 (45.78, 61.30) | 39.01* | 92.31 | − 5.13, p = .492 |

*p < .001

Pooled effect sizes were compared across surgery types. BPD/DS produced significantly greater weight loss compared to all other operation types: RYGB (Q (1)=4.45, p < .05), gastroplasty (Q (1)=8.66, p < .01), LAGB (Q (1)=17.06, p < .001) and sleeve (Q (1)=4.46, p < .05). RYGB produced significantly greater weight loss compared to LAGB (Q (1)=7.62, p < .01).

There were no differences in %EWL between RYGB and sleeve (Q (1)=.30, p = .585), sleeve and gastroplasty (Q (1)=0.29, p = .590), or between LAGB and sleeve (Q (1)=2.01, p = .156), or LAGB and gastroplasty (Q (1)=0.95, p = .330).

CBS Longitudinal Cohort Study

A total of 8378 patients (77.4% female) were treated by primary LAGB procedure. They had a mean age of 42 years (range 14–77 years) and had a mean initial weight of 121.2 kg and a mean initial BMI of 43.2 kg/m2.

Follow-up has been maintained for 54% of patients overall. The loss to follow-up was higher as the follow-up period lengthened. The percent follow-up of each annual cohort is shown in Table 6 and 7.

Table 7.

Single-centre review of weight loss with up to 20 years of follow-up after LAGB

| Year | No. of patients | Weight loss (kg) | 95% CI | % total weight loss | Change of BMI (units) | 95% CI | %EWL | 95% CI | % follow-up |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 8378 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||||

| 1 | 7817 | 21.9 | 0.28 | 18.1 | 7.8 | 0.1 | 45.8 | 0.53 | 92.5 |

| 2 | 7264 | 24.6 | 0.34 | 20.4 | 8.8 | 0.12 | 52.6 | 0.62 | 89.1 |

| 3 | 6877 | 24.5 | 0.39 | 20.3 | 8.7 | 0.14 | 51.4 | 0.66 | 85.0 |

| 4 | 6006 | 24.0 | 0.43 | 19.9 | 8.6 | 0.15 | 49.3 | 0.73 | 69.4 |

| 5 | 5235 | 23.7 | 0.47 | 19.5 | 8.5 | 0.17 | 47.7 | 0.84 | 68.6 |

| 6 | 4570 | 23.2 | 0.50 | 19.2 | 8.3 | 0.18 | 46.4 | 0.93 | 55.0 |

| 7 | 3917 | 22.9 | 0.56 | 19.0 | 8.2 | 0.20 | 45.6 | 0.97 | 46.6 |

| 8 | 3333 | 23.1 | 0.60 | 19.1 | 8.3 | 0.21 | 45.5 | 1.1 | 43.9 |

| 9 | 2768 | 22.9 | 0.65 | 19.0 | 8.2 | 0.23 | 44.8 | 1.1 | 41.9 |

| 10 | 2275 | 23.2 | 0.73 | 19.4 | 8.3 | 0.25 | 45.5 | 1.3 | 39.0 |

| 11 | 1860 | 23.6 | 0.81 | 19.5 | 8.5 | 0.29 | 45.6 | 1.4 | 43.8 |

| 12 | 1472 | 24.1 | 0.91 | 20.1 | 8.7 | 0.33 | 46.7 | 1.6 | 36.6 |

| 13 | 1147 | 24.4 | 1.03 | 20.4 | 8.8 | 0.36 | 46.8 | 1.8 | 41.3 |

| 14 | 827 | 25.4 | 1.26 | 20.9 | 9.1 | 0.44 | 47.7 | 2.0 | 33.8 |

| 15 | 599 | 25.4 | 1.47 | 21.2 | 9.1 | 0.5 | 47.9 | 2.4 | 34.0 |

| 16 | 436 | 25 | 1.75 | 21.1 | 9.0 | 0.63 | 47.1 | 3.0 | 36.5 |

| 17 | 292 | 26.4 | 2.3 | 22.0 | 9.5 | 0.9 | 48.3 | 3.8 | 27.9 |

| 18 | 181 | 27.2 | 3.0 | 22.2 | 9.6 | 1.1 | 47.3 | 4.4 | 23.8 |

| 19 | 95 | 27.2 | 4.0 | 22.1 | 9.5 | 1.4 | 46.1 | 6.0 | 24.6 |

| 20 | 35 | 30.1 | 9.2 | 22.2 | 10.6 | 3.2 | 48.9 | 13.9 | 25.0 |

Mortality

There have been no deaths associated with any primary bariatric procedure or any subsequent revisional procedure. To our awareness, there have been no late deaths that should be attributed to the procedure.

Weight Loss

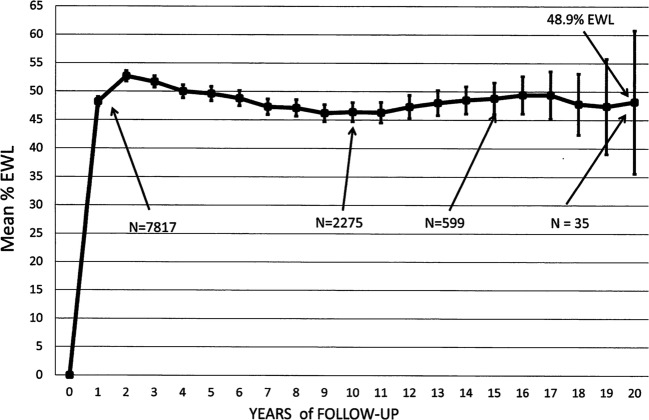

The weight loss over time is shown as kg weight loss, change in BMI, % TWL and %EWL in Table 7 and as %EWL in Fig. 5. Table 7 also shows the number of patients at each annual time point. The weight loss had reached a peak at 2-year follow-up and remained relatively stable from 2 to 20 years with mean weight loss for this period of 24.8 kg representing 47.2 %EWL. Thirty-five patients have completed 20-year follow-up and have maintained a mean loss of 30.1 kg (48.9% EWL, 22.2% TWL) at that time. Nineteen of the 35 patients (54%) had retained a loss of more than 50% of their excess weight at 20 years. Although the number of patients completing 20-year follow-up is modest, much larger numbers have completed 15–19 years as shown on Table 7 and show a very similar weight loss status (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

The weight loss expressed as %EWL ± 95% CI for the 20-year period of follow-up after LAGB. The initial N = 8378 patients. At 20 years, there was 30.1 kg weight loss and 22.2%TWL

Revisional Surgery

The revisional surgery rates for the 3554 patients treated by one surgeon (POB) are shown in Table 8. Enlargements of stomach above the band remain the most common indication for revision and include posterior slips, anterior slips and symmetrical enlargements. Whereas in our initial experience posterior slip was common, the shift to the pars flaccida pathway for band placement has almost totally removed that problem [61]. Anterior slip has been reduced by improved anterior fixation of the stomach across the band and symmetrical enlargement remains the main anatomical abnormality leading to revision. Of the 214 revisions after initial placement of a Lap-Band AP version, introduced in 2006, 197 procedures were for symmetrical enlargement (92%), 12 procedures for anterior slip (5.6%), and 5 procedures for posterior slip (2.3%). The need for revisional surgery for proximal enlargements has decreased markedly in the last 11 years, in association with the use of the Lap-Band AP and improved patient education, moving from more than 50% during the early era to 11.3% for the last 12-year period. Erosion of the band into the gastric lumen has occurred in 114 patients with an overall rate of 3.2%. A detailed clinical report on the first 100 erosions has been published [62]. There has been a marked reduction in this problem in association with the change of band design, decreasing from 6% during the Lap-Band 10 cm era to less than 0.7% in the Lap-Band AP era (Table 8).

Table 8.

Reoperations/revisions during the follow-up period

| Total period | Lap-Band 10 cm era | Lap-Band AP era | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1994–2017 (N = 3554) | 1994–2005 (N = 1658) | 2006–2017 (N = 1896) | |

| Enlargements | 1063 (29.9%) | 847 (51.7%) | 214 (11.3%) |

| Erosions | 114 (3.2%) | 101 (6.1%) | 13 (0.69%) |

| Explantations/conversion | 305 (8.6%) | 199 (12%) | 104 (5.5%) |

| Port/tubing | 760 (21.4%) | 599 (35.7%) | 161 (8.5%) |

Explanations have occurred in 8.6% of patients. The most frequent reason is patient request due to food intolerance.

Port and tubing problems represent a separate and relatively minor array of events. Common problems were needle stick injury to the tubing adjacent to the port, tubing being rubbed through, breakage in the tubing generally adjacent to a metal connector and inaccessibility or rotation of the port.

Discussion

The meta-analysis of published long-term outcomes shows the principal bariatric surgical procedures provide substantial and durable weight loss. The most impressive outcome came from the BPD or its DS variant with a pooled effect size of 71.0% EWL followed by RYGB with 60% EWL and LAGB with 49% EWL.

Data were insufficient for a meta-analysis of the sleeve gastrectomy but it generated a weighted mean of 57% EWL from the two small studies that were included in the systematic review. Similarly, OAGB had just two studies which showed a high weighted mean of 81% EWL. It is appropriate to be cautious when just two studies are available and therefore, we wait expectantly for additional long-term data on both sleeve and OAGB.

The results shown would appear to confirm the greater effectiveness and durability of bariatric surgery compared to optimal medical therapy. The Look AHEAD study which arguably provides the best example of what can be achieved by a concentrated and continuing process of an intensive lifestyle intervention, achieved approximately 15% EWL at 8 years [3].

Whilst it is reassuring to note long-term effectiveness, the quality of most of the studies was low with a general lack of control data, numerous data gaps including percentage follow-up, reoperation rates, perioperative mortality and morbidity and even the measures of variance were absent in several reports. There is a critical need for higher levels of evidence. Only two RCTs have been included [12, 13]. Angrisani et al. compared RYGB and LAGB and showed 69% EWL and 46% EWL respectively [13]. In the Australian study which compared LAGB to optimal medical therapy, the LAGB group showed 63% EWL at 10 years. More recently, three important RCTs of 5-year outcomes with RYGB versus sleeve gastrectomy have been published [63–65]. The SLEEVEPASS study [63] reported 57% EWL for RYGB and 49% EWL for sleeve at 5 years. The SM_BOSS study [64] reported 68% excess BMI lost (EBMIL) for RYGB and 61% EBMIL for sleeve. The STAMPEDE study [65] reported 21.7% TWL for RYGB and 18.5% TWL for sleeve. We look forward to longer follow-up from these and other such studies. It is likely that the broad acceptance of bariatric surgery will not occur until these additional higher quality data become available.

The CBS longitudinal cohort study shows substantial weight loss to be present by 2 years and this effect remained relatively constant for the subsequent 18 years, finishing with a final value of 48.9% EWL and 22.2% TWL at 20 years (N = 35). Only one other study has reported longer follow-up. Gunther et al. [5] followed 198 patients for up to 25 years. For transected RYGB patients, they reported 29.9% EWL at 20 years (N = 53) and 25.5% EWL at 25 years (N = 62) [5]. They reported a net weight gain at 25 years for their gastroplasty patients. The adjustability of the LAGB could be a key factor in maintaining stable weight loss status compared to the progressive fading of effect with non-adjustable stapling procedures.

Revisional surgery was not always reported in the studies within the systematic review but, when provided, showed reoperation was common after all surgical options. The need for reoperation has been seen to be a weakness of LAGB and the reoperation rate for the longitudinal cohort study was high during the Lap-Band 10 cm era with over 50% needing revision for proximal gastric enlargements above the band. The need dropped sharply during the Lap-Band AP era to just over 10%. Part of this lower incidence would reflect lead-time bias. Other factors include an improved band design and better understanding of how the band works [66–68] leading to more appropriate patient education and aftercare support.

In the review of our 15-year outcomes [4], we had provided a table identifying important modifications of the band, its placement and aftercare up to 2012 that were leading to improved outcomes. Two recent additions to that list are worth noting. The first is the use of the mesh fixation of the access port. This technique has added several advantages of less post-operative pain, easier adjustments of the band in the office and less reoperation for needle stick injury or unstable port position. As a consequence, attendance at aftercare is better, leading to improved outcomes. The second important change has been a better focus on slow eating with the strict adherence to a minimum of 1-min duration between bites [68]. This has enabled better control of appetite and reduced incidence of symmetrical enlargement.

The systematic review has shown that all procedures have a substantial need for re-operative surgery and the levels of reoperation for LAGB during the Lap-Band AP at CBS are within the range of other bariatric procedures in the systematic review.

Maintaining completeness of follow-up will always be a major challenge for long-term follow-up studies. Direct contact follow-up was available in the CBS study of 58% overall. This is less than 81% follow up achieved in the 15-year follow-up report [4], in which study we made dedicated effort to bring in as many additional patients as possible. No specific efforts were made for the present study. The 58% achieved for the full 20-year cohort can be compared to the 57% direct contact follow-up achieved at 7 years for the LABS-2 study [69, 70], a well-funded and strongly committed clinical trial.

The studies have several limitations. The quality of the data for the systematic review was low with only two randomised controlled trial available. A total of 18 reports accepted for the systematic review had to be excluded from the meta-analysis because they provided no appropriate measure of variance. The secondary aims of the systematic review could not always be achieved as data on mortality, percentage patients lost to follow up and reoperation rates were not provided in many cases. The relative lack of long-term data for sleeve gastrectomy is of concern as it has already become the most common bariatric procedure [71], yet lacking strong evidence of durability. Notably, the 5-year weight loss from one of the RCTs using the sleeve [63] is the same as our data on the 20-year weight loss for LAGB.

In summary, RYGB, LAGB and BPD/DS lead to substantial weight loss which continues for at least 10 years. Each has an effect size three to four times that of optimal non-surgical therapy. The reoperation rate is significant for each procedure. Long-term data on sleeve gastrectomy and OAGB are modest at this time. Data on LAGB from a single centre shows stability of weight loss at just less than 50% EWL through 20 years. There has been a substantial reduction in reoperation rates associated with improved band design and better quality of patient education due to with improved understanding of how the band works. Guidance to the obese patient should balance durable effectiveness with risks, costs, health benefits and effect on quality of life.

Conflict of Interest

Dr. O’Brien reports grants from Allergan Inc., grants from Apollo Endosurgery and grants from Applied Medical during the conduct of the study.

Dr. Brown reports grants from Johnson and Johnson, grants from Medtronic, grants from GORE, personal fees from GORE, grants from Applied Medical, grants from Apollo Endosurgery, grants and personal fees from Novo Nordisc and personal fees from Merck Sharpe and Dohme.

There were no other reported conflicts of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was not applicable or required for this study.

Contributor Information

Paul E. O’Brien, Email: paul.obrien@monash.edu

Annemarie Hindle, Email: Annemarie.hindle@acu.edu.au.

Leah Brennan, Email: leah.brennan@acu.edu.au.

Stewart Skinner, Email: stewart.skinner@hotmail.com.

Paul Burton, Email: paul.burton@monash.edu.

Andrew Smith, Email: Andrew.smith@giprivate.com.au.

Gary Crosthwaite, Email: gcro2549@bigpond.net.au.

Wendy Brown, Email: wendy.brown@monash.edu.

References

- 1.Heymsfield SB, Wadden TA. Mechanisms, pathophysiology, and management of obesity. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1492. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1514009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heymsfield SB, Bourgeois B, Thomas DM. Why is it difficult to lose and maintain large amounts of weight with lifestyle and pharmacologic treatments? Obesity (Silver Spring) 2017;2017:25. doi: 10.1002/oby.22045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wing RR, Bolin P, Brancati FL, Bray GA, Clark JM, Coday M, Crow RS, Curtis JM, Egan CM, Espeland MA, Evans M, Foreyt JP, Ghazarian S, Gregg EW, Harrison B, Hazuda HP, Hill JO, Horton ES, Hubbard VS, Jakicic JM, Jeffery RW, Johnson KC, Kahn SE, Kitabchi AE, Knowler WC, Lewis CE, Maschak-Carey BJ, Montez MG, Murillo A, Nathan DM, Patricio J, Peters A, Pi-Sunyer X, Pownall H, Reboussin D, Regensteiner JG, Rickman AD, Ryan DH, Safford M, Wadden TA, Wagenknecht LE, West DS, Williamson DF, Yanovski SZ. Cardiovascular effects of intensive lifestyle intervention in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:145–154. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1212914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Brien P, McDonald L, Anderson M, Brennan L, Brown WA. Long term outcomes after bariatric surgery: fifteen year follow up after gastric banding and a systematic review of the literature. Ann Surg. 2013;257:87–94. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31827b6c02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Günther K, Vollmuth J, Weißbach R, Hohenberger W, Husemann B, Horbach T. Weight reduction after an early version of the open gastric bypass for morbid obesity: results after 23 years. Obes Surg. 2006;16:288–296. doi: 10.1381/096089206776116543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sjostrom L. Review of the key results from the swedish obese subjects (sos) trial - a prospective controlled intervention study of bariatric surgery. J Intern Med. 2013;273:219–234. doi: 10.1111/joim.12012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew M, Shekelle P, Stewart LA. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (prisma-p) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4:1. doi: 10.1186/2046-4053-4-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Golzarand M, Toolabi K, Farid R. The bariatric surgery and weight losing: a meta-analysis in the long- and very long-term effects of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy on weight loss in adults. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:4331–4345. doi: 10.1007/s00464-017-5505-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Juodeikis Z, Brimas G. Long-term results after sleeve gastrectomy: a systematic review. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:693–699. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Puzziferri N, Roshek TB, III, Mayo HG, Gallagher R, Belle SH, Livingston EH. Long-term follow-up after bariatric surgery: a systematic review. JAMA. 2014;312:934–942. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.10706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, Torgerson J, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, Dahlgren S, Larsson B, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, Sullivan M, Wedel H. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2683–2693. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Brien PE, Brennan L, Laurie C, Brown W. Intensive medical weight loss or laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in the treatment of mild to moderate obesity: long-term follow-up of a prospective randomised trial. Obes Surg. 2013;23:1345–1353. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-0990-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angrisani L, Cutolo PP, Formisano G, Nosso G, Vitolo G. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding versus Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 10-year results of a prospective, randomized trial. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:405–413. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fobi MA. Vertical banded gastroplasty vs gastric bypass: 10 years follow-up. Obes Surg. 1993;3:161–164. doi: 10.1381/096089293765559511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wolfel R, Gunther K, Rumenapf G, Koerfgen P, Husemann B. Weight reduction after gastric bypass and horizontal gastroplasty for morbid obeisty. Results after 10 years. Eur J Surg. 1994;160:219–225. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pories WJ, Swanson MS, MacDonald KG, Long SB, Morris PG, Brown BM, Barakat HA, de Ramon RA, Israel G, Dolezal JM, et al. Who would have thought it? An operation proves to be the most effective therapy for adult-onset diabetes mellitus. Ann Surg. 1995;222:339–350. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199509000-00011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sugerman HJ, Wolfe LG, Sica DA, Clore JN. Diabetes and hypertension in severe obesity and effects of gastric bypass-induced weight loss. Ann Surg. 2003;237:751–756. doi: 10.1097/01.SLA.0000071560.76194.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Christou NV, Look D, MacLean LD. Weight gain after short- and long-term gastric bypass in patients followed for longer than 10 years. Ann Surg. 2006;244:734–740. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000217592.04061.d5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sjostrom L, Narbro K, Sjostrom CD, Karason K, Larsson B, Wedel H, Lystig T, Sullivan M, Bouchard C, Carlsson B, Bengtsson C, Dahlgren S, Gummesson A, Jacobson P, Karlsson J, Lindroos AK, Lonroth H, Naslund I, Olbers T, Stenlof K, Torgerson J, Agren G, Carlsson LM. Effects of bariatric surgery on mortality in swedish obese subjects. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:741–752. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa066254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Higa K, Ho T, Tercero F, Yunus T, Boone KB. Laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 10-year follow-up. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2011;7:516–525. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2010.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Obeid NR, Malick W, Concors SJ, Fielding GA, Kurian MS, Ren-Fielding CJ. Long-term outcomes after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 10- to 13-year data. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2015.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Corsino L, Shantavasinkul PC, Grant J, Portenier D, Ding L, Torquati A. Gastric bypass surgery leads to long-term remission or improvement of type 2 diabetes and significant decrease of microvascular and macrovascular complications. Ann Surg. 2016;263:1138–1142. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maciejewski ML, Arterburn DE, Van Scoyoc L, Smith VA, Yancy WS, Weidenbacher HJ, Livingston EH, Olsen MK. Bariatric surgery and long-term durability of weight loss. JAMA Surg. 2016;151:1046–1055. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2016.2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Monaco-Ferreira DV, Leandro-Merhi VA. Weight regain 10 years after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2017;27:1137–1144. doi: 10.1007/s11695-016-2426-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Valezi AC, De Almeida Menezes M, Mali J., Jr Weight loss outcome after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 10 years of follow-up. Obes Surg. 2013;23:1290–1293. doi: 10.1007/s11695-013-0908-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehaffey JH, LaPar DJ, Clement KC, Turrentine FE, Miller MS, Hallowell PT, Schirmer BD. 10-year outcomes after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Ann Surg. 2016;264:121–126. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kothari SN, Borgert AJ, Kallies KJ, Baker MT, Grover BT. Long-term (>10-year) outcomes after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:972–978. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Carbajo MA, Luque-de-Leon E, Jimenez JM, Ortiz-de-Solorzano J, Perez-Miranda M, Castro-Alija MJ. Laparoscopic one-anastomosis gastric bypass: technique, results, and long-term follow-up in 1200 patients. Obes Surg. 2017;27:1153–1167. doi: 10.1007/s11695-016-2428-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sheikh L, Pearless LA, Booth MW. Laparoscopic silastic ring mini-gastric bypass (sr-mgbp): up to 11-year results from a single centre. Obes Surg. 2017;27:2229–2234. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2659-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller K, Pump A, Hell E. Vertical banded gastroplasty versus adjustable gastric banding: prospective long-term follow-up study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2007;3:84–90. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2006.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Favretti F, Segato G, Ashton D, Busetto L, De Luca M, Mazza M, Ceoloni A, Banzato O, Calo E, Enzi G. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in 1,791 consecutive obese patients: 12-year results. Obes Surg. 2007;17:168–175. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9043-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Naef M, Mouton W, Naef U, Kummer O, Muggli B, Wagner H. Graft survival and complications after laparoscopic gastric banding for morbid obesity—lessons learned from a 12-year experience. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1206–1214. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0205-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Himpens J, Cadiere GB, Bazi M, Vouche M, Cadiere B, Dapri G. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Arch Surg. 2011;146:802–807. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stroh C, Hohmann U, Schramm H, Meyer F, Manger T. Fourteen-year long-term results after gastric banding. J Obes. 2011;2011:128451–128457. doi: 10.1155/2011/128451. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Aarts EO, Dogan K, Koehestanie P, Aufenacker TJ, Janssen IMC, Berends FJ. Long-term results after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: a mean fourteen year follow-up study. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2014;10:633–640. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2014.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Arapis K, Tammaro P, Parenti LR, Pelletier AL, Chosidow D, Kousouri M, Magnan C, Hansel B, Marmuse JP. Long-term results after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for morbid obesity: 18-year follow-up in a single university unit. Obes Surg. 2017;27:630–640. doi: 10.1007/s11695-016-2309-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Victorzon M, Tolonen P. Mean fourteen-year, 100% follow-up of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding for morbid obesity. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2013;9:753–757. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2013.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kowalewski PK, Olszewski R, Kwiatkowski A, Galazka-Swiderek N, Cichon K, Pasnik K. Life with a gastric band. Long-term outcomes of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding-a retrospective study. Obes Surg. 2017;27:1250–1253. doi: 10.1007/s11695-016-2435-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carandina S, Tabbara M, Galiay L, Polliand C, Azoulay D, Barrat C, Lazzati A. Long-term outcomes of the laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: weight loss and removal rate. A single center experience on 301 patients with a minimum follow-up of 10 years. Obes Surg. 2017;27:889–895. doi: 10.1007/s11695-016-2391-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Toolabi K, Golzarand M, Farid R. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: efficacy and consequences over a 13-year period. Am J Surg. 2016;212:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2015.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Trujillo MR, Muller D, Widmer JD, Warschkow R, Muller MK. Long-term follow-up of gastric banding 10 years and beyond. Obes Surg. 2016;26:581–587. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1800-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vinzens F, Kilchenmann A, Zumstein V, Slawik M, Gebhart M, Peterli R. Long-term outcome of laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (lagb): results of a swiss single-center study of 405 patients with up to 18 years’ follow-up. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2017;13:1313–1319. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2017.04.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hess DS, Hess DW, Oakley RS. The biliopancreatic diversion with the duodenal switch: results beyond 10 years. Obes Surg. 2005;15:408–416. doi: 10.1381/0960892053576695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Scopinaro N, Marinari GM, Camerini GB, Papadia FS, Adami GF. Specific effects of biliopancreatic diversion on the major components of metabolic syndrome: a long-term follow-up study. Diabetes Care. 2005;28:2406–2411. doi: 10.2337/diacare.28.10.2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larrad-Jiménez Á, Sánchez-Cabezudo Díaz-Guerra C, de Cuadros Borrajo P, Bretón Lesmes I, Moreno Esteban B. Short-, mid- and long-term results of Larrad biliopancreatic diversion. Obes Surg. 2007;17:202–210. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9035-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ballesteros-Pomar MD, Gonzalez de Francisco T, Urioste-Fondo A, Gonzalez-Herraez L, Calleja-Fernandez A, Vidal-Casariego A, Simo-Fernandez V, Cano-Rodriguez I. Biliopancreatic diversion for severe obesity: long-term effectiveness and nutritional complications. Obes Surg. 2016;26:38–44. doi: 10.1007/s11695-015-1719-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bolckmans R, Himpens J. Long-term (>10 yrs) outcome of the laparoscopic biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. Ann Surg. 2016;264:1029–1037. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000001622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Camerini GB, Papadia FS, Carlini F, Catalano M, Adami GF, Scopinaro N. The long-term impact of biliopancreatic diversion on glycemic control in the severely obese with type 2 diabetes mellitus in relation to preoperative duration of diabetes. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:345–349. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sethi M, Chau E, Youn A, Jiang Y, Fielding G, Ren-Fielding C. Long-term outcomes after biliopancreatic diversion with and without duodenal switch: 2-, 5-, and 10-year data. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:1697–1705. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pata G, Crea N, Di Betta E, Bruni O, Vassallo C, Mittempergher F. Biliopancreatic diversion with transient gastroplasty and duodenal switch: long-term results of a multicentric study. Surgery. 2013;153:413–422. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2012.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Topart P, Becouarn G, Delarue J. Weight loss and nutritional outcomes 10 years after biliopancreatic diversion with duodenal switch. Obes Surg 2017;27:1645–50. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 52.Marceau P, Biron S, Hould FS, Lebel S, Marceau S, Lescelleur O, Biertho L, Simard S. Duodenal switch: long-term results. Obes Surg. 2007;17:1421–1430. doi: 10.1007/s11695-008-9435-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.White S, Brooks E, Jurikova L, Stubbs RS. Long-term outcomes after gastric bypass. Obes Surg. 2005;15:155–163. doi: 10.1381/0960892053268282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Arman GA, Himpens J, Dhaenens J, Ballet T, Vilallonga R, Leman G. Long-term (11+years) outcomes in weight, patient satisfaction, comorbidities, and gastroesophageal reflux treatment after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:1778–1786. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Felsenreich DM, Langer FB, Kefurt R, Panhofer P, Schermann M, Beckerhinn P, Sperker C, Prager G. Weight loss, weight regain, and conversions to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 10-year results of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2016;12:1655–1662. doi: 10.1016/j.soard.2016.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Scozzari G, Toppino M, Famiglietti F, Bonnet G, Morino M. 10-year follow up of laparoscopic vertical banded gastroplasty: good results in selected patients. Ann Surg. 2010;252:831–839. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181fd35b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lin YH, Lee WJ, Ser KH, Chen SC, Chen JC. 15-year follow-up of vertical banded gastroplasty: comparison with other restrictive procedures. Surg Endosc. 2016;30:489–494. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4230-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Canetti L, Bachar E, Bonne O. Deterioration of mental health in bariatric surgery after 10 years despite successful weight loss. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2016;70:17–22. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2015.112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Talebpour M, Motamedi SMK, Talebpour A, Vahidi H. Twelve year experience of laparoscopic gastric plication in morbid obesity: development of the technique and patient outcomes. Ann Surg Innov Res. 2012;6:7–7. doi: 10.1186/1750-1164-6-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.O’Brien PE, Dixon JB, Laurie C, Anderson M. A prospective randomized trial of placement of the laparoscopic adjustable gastric band: comparison of the perigastric and pars flaccida pathways. Obes Surg. 2005;15:820–826. doi: 10.1381/0960892054222858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brown WA, Egberts KJ, Franke-Richard D, Thodiyil P, Anderson ML, O’Brien PE. Erosions after laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: diagnosis and management. Ann Surg. 2013;257:1047–1052. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e31826bc21b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Salminen P, Helmio M, Ovaska J, Juuti A, Leivonen M, Peromaa-Haavisto P, Hurme S, Soinio M, Nuutila P, Victorzon M. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss at 5 years among patients with morbid obesity: the sleevepass randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:241–254. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Peterli R, Wolnerhanssen BK, Peters T, Vetter D, Kroll D, Borbely Y, Schultes B, Beglinger C, Drewe J, Schiesser M, Nett P, Bueter M. Effect of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy vs laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass on weight loss in patients with morbid obesity: the SM-BOSS randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2018;319:255–265. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.20897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schauer PR, Bhatt DL, Kirwan JP, Wolski K, Aminian A, Brethauer SA, Navaneethan SD, Singh RP, Pothier CE, Nissen SE, Kashyap SR. Bariatric surgery versus intensive medical therapy for diabetes - 5-year outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:641–651. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1600869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burton PR, Brown WA, Laurie C, Hebbard G, O’Brien PE. Mechanisms of bolus clearance in patients with laparoscopic adjustable gastric bands. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1265–1272. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-0063-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Burton PR, Yap K, Brown WA, Laurie C, O’Donnell M, Hebbard G, Kalff V, O’Brien PE. Effects of adjustable gastric bands on gastric emptying, supra- and infraband transit and satiety: a randomized double-blind crossover trial using a new technique of band visualization. Obes Surg. 2010;20:1690–1697. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0278-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Burton PR, Yap K, Brown WA, Laurie C, O'Donnell M, Hebbard G, Kalff V, O’Brien PE. Changes in satiety, supra- and infraband transit, and gastric emptying following laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding: a prospective follow-up study. Obes Surg. 2011;21:217–223. doi: 10.1007/s11695-010-0312-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Courcoulas AP, King WC, Belle SH, Berk P, Flum DR, Garcia L, Gourash W, Horlick M, Mitchell JE, Pomp A, Pories WJ, Purnell JQ, Singh A, Spaniolas K, Thirlby R, Wolfe BM, Yanovski SZ. Seven-year weight trajectories and health outcomes in the longitudinal assessment of bariatric surgery (labs) study. JAMA Surg 2018;153:427–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 70.Higa KD, Himpens J. The reality of long-term follow-up of bariatric/metabolic surgery patients-a conundrum. JAMA Surg 2018;153:435. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 71.Angrisani L. 2014: the year of the sleeve supremacy. Obes Surg. 2017;27:1626–1627. doi: 10.1007/s11695-017-2681-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]