Mitochondrial metabolism encompasses pathways that generate ATP to drive intracellular unfavorable energetic reactions and produce the building blocks necessary for macromolecule synthesis. In the past two decades, it has become clear that mitochondrial metabolism does not play a passive role as an underlying mechanism of biology, but instead plays a dynamic and influential role in dictating cell fate and function by controlling gene expression through release of reactive oxygen species and metabolites (1). The compartmentalization of mitochondrial enzymes and complexes is essential for the maintenance of important signaling pathways within the cell. For this reason, the identity and concentration of metabolites is substantially different between the mitochondrial matrix and the cytosol. To date, much of our understanding of the concentration of mitochondrial metabolites has been limited to in vitro settings (2). In PNAS, Bayraktar et al. (3) establish MITO-Tag Mice, a tool that will have a substantial impact on the understanding of in vivo mitochondrial metabolism by allowing rapid assessment of mitochondrial metabolites.

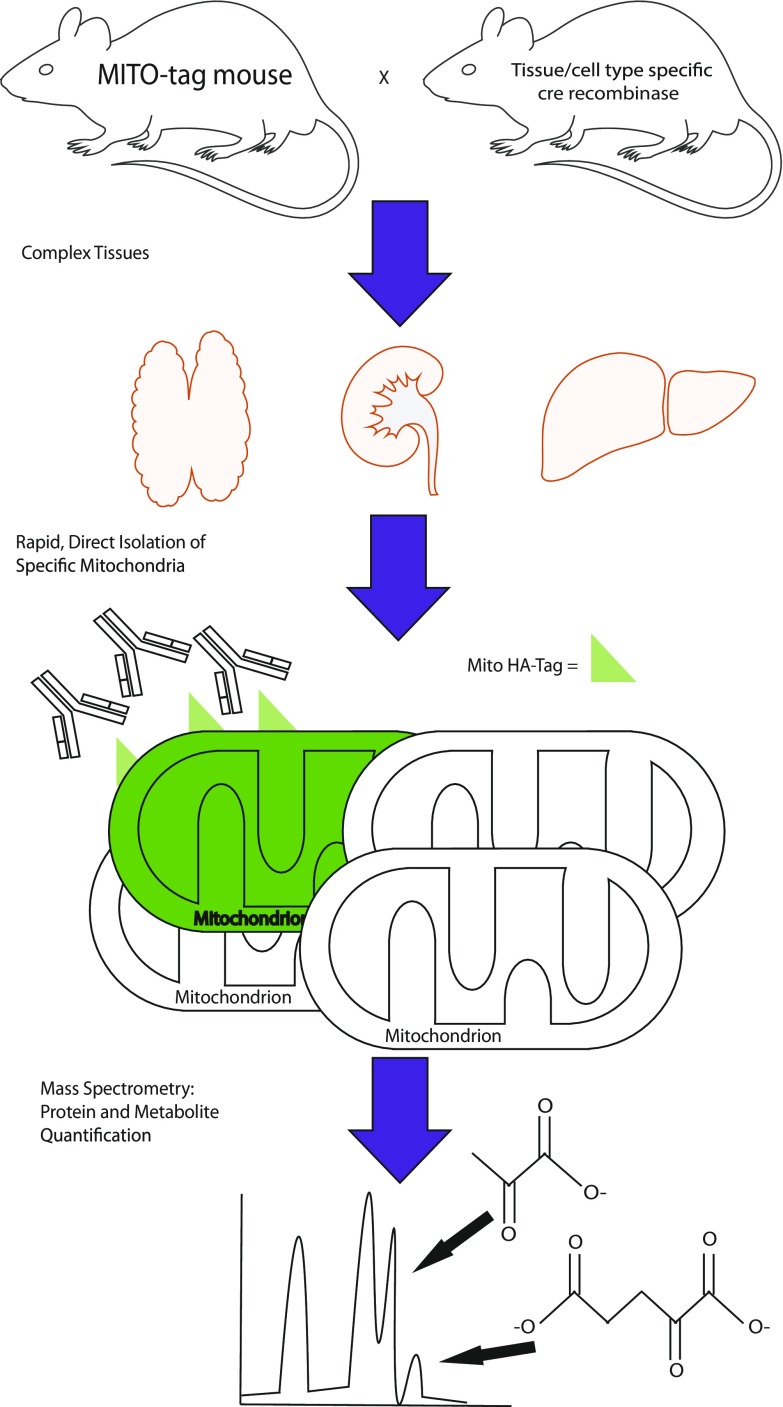

MITO-Tag Mice take advantage of the mitochondrial localization sequences of the outer mitochondrial membrane protein OMP25 to target a fusion protein containing the HA epitope from influenza hemagglutinin and GFP to the mitochondria. This MITO-Tag was previously published for in vitro use (2, 4). This methodology allowed the rapid isolation of tagged mitochondria from cells cultured in vitro using antibodies specific to the HA epitope. Now, in PNAS, Bayraktar et al. (3) take the important next step by generating a mouse model that expresses the MITO-Tag in specific cell types in vivo, using Cre-Lox recombination technology (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

MITO-Tag Mice use Cre-Lox recombination to express a mitochondria-targeted epitope tag in specific cell types or tissues. This epitope tag allows the rapid and direct isolation of mitochondria from the cell types or tissues of interest. Mitochondria isolated from these tissues can then be analyzed using multiomic approaches, including metabolite and protein identification and quantification by mass spectrometry.

Bayraktar et al. (3) generated MITO-Tag Mice by knocking a construct containing loxP-STOP-loxP followed by the sequence encoding the fusion MITO-Tag protein into the Rosa26 locus. The authors demonstrate the functionality of this mouse model by crossing MITO-Tag Mice to the liver-specific Albumin-Cre mouse. Upon expression of the bacterial Cre enzyme in the liver under the control of the hepatocyte-specific albumin promotor, Bayraktar et al. demonstrate that the MITO-Tag localizes to the mitochondria of hepatocytes. Anti-HA immunoprecipitation leads to the specific isolation of these mitochondria. Next, the authors demonstrate the application of their model by performing multiomic characterization of hepatic mitochondria. First, they performed proteomic analyses and identified over 500 proteins present in hepatic mitochondria. Next, they measured metabolites by mass spectrometric approaches and identified multiple metabolite species predicted to be present in mitochondria, including several lipid species that are specific to the mitochondrial membrane. Subsequently, they compared metabolite levels from mice in the fasted versus the fed state in both whole liver tissue and isolated hepatocyte mitochondria. Bayraktar et al. demonstrate that their tool is able to detect changes in mitochondrial metabolite abundance that occur in the fasted versus fed state that are not detectable at the level of whole tissue. For example, in the fasted state, methionine and alanine are significantly depleted and enriched, respectively, in mitochondria, while these metabolite levels do not significantly change in whole tissue.

Why does specifically isolating compartments of the cell matter? An analogy that has previously been used for contextualizing the compartmentalization of metabolites is the localization of weather forecasting within different parts of a state (5). For example, an individual visiting the beautiful mountains of a state might experience several inches of snow while another individual in a nearby city might experience a sunny day. Similarly, measuring the metabolite abundance in the whole tissue is analogous to averaging the weather of the entire state, while targeting subcellular organelles of specific cell types is analogous to the weather of a single region or city. The local microenvironment is very important for our understanding of biology.

MITO-Tag Mice overcome two of the main challenges of the current methods for isolation from mouse tissue: (i) the length of time and perturbation of the organelle during isolation and (ii) the specificity of the cell type of origin. Previously, direct isolation of mitochondria from tissue did not allow for specific isolation of mitochondria from cell types of interest. This can be problematic in complex tissues with heterogeneous cell populations. Furthermore, this method also typically requires density-gradient centrifugation steps, which take time and may result in artificial changes in the transient abundance of metabolites within the mitochondria. The previous protocols for isolation of mitochondria from specific cell types would take even longer and would involve, first, tissue dissociation and isolation of the cell types of interest (e.g., by FACS), followed by cellular disruption for mitochondrial isolation. MITO-Tag Mice (3) address the problems of time and specificity of mitochondrial isolation by allowing researchers to bypass steps that identify specific cell types and gradient centrifugation steps due to the genetically introduced epitope tag. The MITO-Tag approach is a superior method for isolation, particularly when the desired experimental output is the quantification of metabolites. This is because levels of metabolites are more susceptible than levels of protein or nucleic acid to rapid perturbation by the isolation process. The reason for this susceptibility is the persistence of not only the enzymes that catalyze metabolic reactions but also the transporters and channels that allow metabolites to rapidly pass through the mitochondrial membrane.

How might this technique be useful to probe mitochondrial metabolism in vivo? We propose two sets of experiments in the areas of diabetes and immunology. First, the target of the widely used antidiabetic drug metformin remains elusive. Oral administration of metformin has been shown to accumulate within the liver, intestines, kidneys, and muscle (6). Metformin has also been proposed to exert antidiabetic effects by altering the gut microbiome (7). Potential targets of metformin within hepatocytes include mitochondrial glycerophosphate dehydrogenase (GPDH) and mitochondrial complex I, causing changes in the NAD/NADH ratio, inhibition of fructose-1,6-bisphosphatase, and AMP-activated protein kinase activation (8–10). MITO-Tag Mice could be used to rapidly assess whether oral administration of metformin at the antidiabetic dose changes the NAD/NADH ratio as well as TCA cycle metabolites within liver mitochondria. Although this would not establish causality of whether metformin targets mitochondrial metabolism, it would demonstrate whether metformin accumulates to a concentration high enough to inhibit mitochondrial GPDH or mitochondrial complex I.

A second set of experiments would be to decipher mitochondrial metabolism of T cells during an infection. Naive T cells are activated and rapidly proliferate in response to an antigen. These effector cells are important for containing an infection and produce long-lasting memory T cells after the infection is gone. Memory T cells can later be summoned to fight off the same infectious agent. Currently, most metabolite profiling in T cell subsets has been done in vitro (11). This has led to a simplistic model in which effector T cells are glycolytic, while memory T cells and T regulatory cells are oxidative (12). It is likely that all T cell subsets utilize glycolysis and mitochondrial metabolism for different purposes during the course of an infection in vivo. It would be valuable to examine metabolite changes within mitochondria of naive T cells, effector T cells, and memory T cells during an infection using MITO-Tag Mice. Similarly, mitochondrial metabolites within macrophage populations could be examined during the course of an infection. One emerging theme in immunometabolism is that TCA cycle metabolites—α-ketoglutarate, succinate, and fumarate—are key regulators of histone acetylation as well as histone and DNA methylation (1). Thus, deciphering whether these TCA cycle metabolites are altered in T cell subsets or macrophages could provide insight into the interconnection of mitochondrial metabolism and changes in gene expression.

MITO-Tag Mice are also exciting as a general mechanism for generating in vivo tags for the isolation of other subcellular organelles. For example, Abu-Remaileh et al. (13) generated a very similar HA lysosomal tag that allows the direct isolation of lysosomes from cells in vitro. The nucleus is also a potential target for this type of tagging for specific metabolite concentration analysis. Quantification of nuclear metabolite abundance is of interest because posttranslational modification of histones and DNA methylation require soluble metabolites to serve as substrates for the addition and removal of the markers that control chromatin accessibility and gene expression (1). With MITO-Tag Mice, Bayraktar et al. (3) provide proof of concept of an in vivo tool and an approach that will open the door to better understanding cellular metabolism of different organelles in vivo.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement: N.S.C. has collaborated with David M. Sabatini and Kivanç Birsoy.

See companion article on page 303.

References

- 1.Mehta MM, Weinberg SE, Chandel NS. Mitochondrial control of immunity: Beyond ATP. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:608–620. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen WW, Freinkman E, Wang T, Birsoy K, Sabatini DM. Absolute quantification of matrix metabolites reveals the dynamics of mitochondrial metabolism. Cell. 2016;166:1324–1337.e11. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bayraktar EC, et al. MITO-Tag Mice enable rapid isolation and multimodal profiling of mitochondria from specific cell types in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2019;116:303–312. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1816656115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen WW, Freinkman E, Sabatini DM. Rapid immunopurification of mitochondria for metabolite profiling and absolute quantification of matrix metabolites. Nat Protoc. 2017;12:2215–2231. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2017.104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Van Vranken JG, Rutter J. The whole (cell) is less than the sum of its parts. Cell. 2016;166:1078–1079. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gormsen LC, et al. In vivo imaging of human 11C-metformin in peripheral organs: Dosimetry, biodistribution, and kinetic analyses. J Nucl Med. 2016;57:1920–1926. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.116.177774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sun L, et al. Gut microbiota and intestinal FXR mediate the clinical benefits of metformin. Nat Med. 2018;24:1919–1929. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0222-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fullerton MD, et al. Single phosphorylation sites in Acc1 and Acc2 regulate lipid homeostasis and the insulin-sensitizing effects of metformin. Nat Med. 2013;19:1649–1654. doi: 10.1038/nm.3372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hunter RW, et al. Metformin reduces liver glucose production by inhibition of fructose-1-6-bisphosphatase. Nat Med. 2018;24:1395–1406. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0159-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madiraju AK, et al. Metformin suppresses gluconeogenesis by inhibiting mitochondrial glycerophosphate dehydrogenase. Nature. 2014;510:542–546. doi: 10.1038/nature13270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Michalek RD, et al. Cutting edge: Distinct glycolytic and lipid oxidative metabolic programs are essential for effector and regulatory CD4+ T cell subsets. J Immunol. 2011;186:3299–3303. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.O’Neill LA, Kishton RJ, Rathmell J. A guide to immunometabolism for immunologists. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:553–565. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abu-Remaileh M, et al. Lysosomal metabolomics reveals V-ATPase- and mTOR-dependent regulation of amino acid efflux from lysosomes. Science. 2017;358:807–813. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]