Significance

Despite the importance of international migration, estimates of between-country migration flows are still imprecise. Reliable record keeping of migration events is typically available only in the developed world, and the best existing methods to produce global migration flow estimates are burdened by strong assumptions. We produce estimates of migration flows between all pairs of countries at 5-year intervals, revealing patterns obscured by previous estimation methods. In particular, our estimates reveal large bidirectional movements in all global regions, with roughly one-quarter of migration events consisting of returns to an individual’s country of birth.

Keywords: bilateral migration flows, international migration, pseudo-Bayes estimation

Abstract

We propose a method for estimating migration flows between all pairs of countries that allows for decomposition of migration into emigration, return, and transit components. Current state-of-the-art estimates of bilateral migration flows rely on the assumption that the number of global migrants is as small as possible. We relax this assumption, producing complete estimates of all between-country migration flows with genuine estimates of total global migration. We find that the total number of individuals migrating internationally has oscillated between 1.13 and 1.29% of the global population per 5-year period since 1990. Return migration and transit migration are big parts of total migration; roughly one of four migration events is a return to an individual’s country of birth. In the most recent time period, we estimate particularly large return migration flows from the United States to Central and South America and from the Persian Gulf to south Asia.

In many developed countries, volatility in population is now largely driven by international migration rather than fertility or mortality (1). However, migration remains difficult to estimate (2, 3). This difficulty is especially pronounced in the context of return migration, the estimation of which may be hindered by unauthorized migration and poor administrative data collection in the developing world (4, 5). Nevertheless, some attempts have been made to produce and/or aggregate high-quality migration flow estimates for limited groups of countries. The Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development (OECD) has compiled estimates of annual migration flows to and from 34 of the current 35 OECD member states in their statistical database (6). (The missing country is Latvia, which joined in July 2016 after the data were published.) Another set of flow estimates was produced by the Integrated Modelling of European Migration (IMEM) project (7). These consist of estimated total flows between all pairs of 31 European countries and were produced using population register data on arrivals and departures where available combined with expert-influenced estimates of undercounting of migration flows. These two sets of estimates largely cover flows where either the origin or the destination country is economically developed. There is little reliable data available on “south–south” flows for which both the origin and the destination country are members of the global south. We address this shortfall with a method for estimating global bilateral migration flows, which in contrast to the current state-of-the-art method (8), does not rely on an assumption that migration counts will be as small as possible.

Although net migration is enough to describe population change due to migration, effective migration policy requires knowledge of the underlying flows.* Typically, migration policy aims to limit or facilitate in-migration (e.g., through entry visas) or to some extent, to encourage or discourage out-migration (e.g., through nonrenewal of existing visas). Moreover, in contemporary democratic societies, the available regulations are limited in that restrictions on out-migration are generally not allowed. Thus, appropriate planning of migration policy requires accurate data on in- and out-migration flows, which are currently inadequate in much of the developing world.

Results

Recent methodological advances led to the first complete global estimates of bilateral migration flows in 2013 (8) constructed on the basis of observed changes in migrant stocks, which are easy to measure relative to directly counting flows. However, the statistical model underlying these state-of-the-art estimates relies on a strong assumption that the number of global migrants is as small as possible while maintaining consistency with changes in population by place of birth. As such, the only migration flow estimates currently available on a global scale are best viewed as a lower bound on global migration. [For brevity, we will refer to these existing global flow estimates as “minimum migration” (MM) estimates in contrast to our estimates, which we call “pseudo-Bayes” (PB) estimates.] By relaxing the assumption on total migration, we produce estimates of true flows between all pairs of countries. This is in contrast to the MM estimates, which although they provide a lower bound on global migration, were never attempting to estimate true flows. In so doing, we also alleviate the MM method’s propensity to underestimate return migration, resulting in estimates of in- and outflows that are more plausible at the finest level of granularity (i.e., flows indexed by all of origin, destination, and place of birth) and may, therefore, be of more use in forecasting quantities like the number of Mexican-born individuals returning from the United States to Mexico.

Our method improves over the existing MM estimates by estimating the extent of cross-flows—that is, simultaneous movement along both directions of a migration corridor. Cross-flows are precluded in the MM estimates by the MM constraint. For example, in the MM estimates, there can be a nonzero flow of Mexican-born individuals from Mexico to the United States or from the United States to Mexico in each time period but never nonzero flows in both directions simultaneously. In reality, we expect to observe substantial churn as migrant populations are simultaneously depleted by departures and replenished by new arrivals, although this process is not visible as a change in migrant stocks. The key innovation in our method is to quantify the extent of churn in global migrant populations and incorporate it into flow estimates in a way that retains consistency with observed changes in migrant stocks. Inference about the extent of churn is based on the limited collection of OECD and IMEM flow estimates (6, 9, 10). Our estimates combine empirical information about cross-flows with the demographic balancing equation based on migrant stocks (11), births and deaths (12), and the MM methodology (8) to produce flow estimates covering 5-y intervals from 1990–1995 to 2010–2015.

Definitional consistency is a ubiquitous problem in estimation of international migration. For the purposes of this paper, we define a 5-y migration flow from country to country as the number of individuals who resided in country at the start of the 5-y time period and in country at the end of the time period, regardless of any other moves made in the interim. This transition-based definition of migration undercounts the total number of moves during the 5-y time period and also poses problems for translation between 1- and 5-y transitions (13–15). Compounding the problem, the criteria for who should be counted as part of the migrant population are also not straightforward, as countries’ official statistics offices make different choices about the requisite duration of stay required to constitute a migration (9). All results in this paper rely on the 2015 revision of the migrant stock estimates published by the United Nations (11), which discusses in the associated documentation the challenges of differing definitions in national data sources and their efforts at harmonization. We use their stock estimates without additional adjustment but note that definitional inconsistencies may propagate through to errors in migration flow estimates.

Total Global Migration Flows.

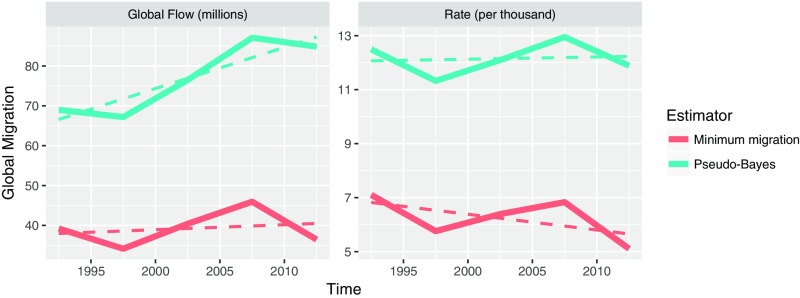

A key finding in our results is that the total number of migration events in each time period may be substantially larger than previously believed. The MM method reports a lower bound on total migration flow between 34 and 46 million migration events globally for each time period from 1990–1995 to 2010–2015. In contrast, our method produces estimates of between 67 and 87 million—at least 75% higher than the MM estimates in all periods and as much as 132% higher in 2010–2015 (Fig. 1, Left). As a proportion of the global population, we estimate that between 1.13 and 1.29% of the world’s population migrated in each 5-y time period. While the number of migrants has risen since 1990–1995, there is no evidence that the proportion of the world’s population migrating has grown.

Fig. 1.

(Left) Estimated global migration counts in millions of migrants. (Right) Estimated global migration rate per thousand individuals. Both plots compare MM estimates (red) with PB estimates (blue) and include dashed ordinary least-squares regression lines over the five time periods of study.

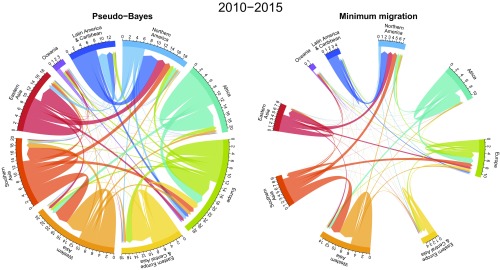

Fig. 2 displays the PB estimates of migration flows for 2010–2015 alongside the MM estimates on a circular migration plot. This style of plot condenses large flow matrices into a form that makes it easy to distinguish the relative magnitudes of flows (16, 17). International migrant flows are depicted with arrows pointing from the region of origin to the region of destination. Colors distinguish the region of origin. Tick marks along the circumference give the size of the flow in millions of migrants.

Fig. 2.

Estimated migration flows for 2010–2015. (Left) PB estimates. (Right) MM estimates. Plots are scaled so that equal angles along the circumference of the circle represent equal numbers of migrants.

Although the PB estimates are higher than the MM estimates in total, the two sets of estimates are broadly similar in composition. For example, both sets of estimates contain large within-region flows in Africa and western Asia, because these flows are necessary to account for observed changes in migrant stocks. Time trends across the 1990–2015 period are similar as well; both sets of estimates contain large flows from southern to western Asia from 2005 onward and from Latin America to northern America, which peak during the 1990s. (Plots for all five quinquennial periods are available in SI Appendix.)

However, despite similar overall patterns, we estimate pronounced cross-flows, especially in countries with large migrant stocks from one or several origins (e.g., Latin Americans in the United States or Turkish-born individuals in Germany). For example, in 2010–2015, the MM method estimates a flow of 2.2 million individuals from Latin America and the Caribbean to northern America but only 190,000 in the opposite direction. Our method increases both of these estimates, with 4.8 million from Latin America and the Caribbean to northern America and 2.8 million in the reverse direction. The net impact of Latin America/northern America migration in the two sets of estimates is nearly identical; 2.0 million individuals are gained by northern America. The higher estimated outflows from northern America in our method are offset by higher inflows so that the net effect of migration is unchanged.

Emigration, Return, and Transit Flows.

Among fully disaggregated flows broken down by place of birth (Table 1), some of the largest flows in 2010–2015 are emigrations from individuals’ country of birth in the form of either continued movement along well-established migration corridors (Mexico to the United States and Bangladesh to India) or refugee out-migration (from Syria to its neighbors). Notably, each of the four largest return flows (the United States to Mexico, United Arab Emirates to India, Ukraine to Russia, and India to Bangladesh) is estimated as being exactly 0 under the MM method, while our estimate for each is at least 350,000 individuals. The ability to project the expected magnitude of such return flows may aid countries in setting in-migration thresholds to meet net migration targets in the future. Transit migration, in which neither the origin nor the destination are the same as the place of birth, is typically lower in magnitude than emigration or return migration. Three of the four most common transit migration scenarios in our estimates share the feature that both the countries of birth and origin have experienced recent instability, with transit migrants in 2010–2015 most commonly leaving Libya, Sudan, Syria, and Saudi Arabia.

Table 1.

Largest emigration, return, and transit flows in 2010–2015 in thousands of individuals listed by place of birth, origin, and destination of flow

| POB | Origin | Destination | MM | PB |

| Emigration | ||||

| Mexico | Mexico | United States | 758 | 2,067 (927–4,610) |

| Syria | Syria | Turkey | 1,537 | 1,534 (688–3,421) |

| Syria | Syria | Lebanon | 1,157 | 1,156 (518–2,578) |

| Bangladesh | Bangladesh | India | 613 | 965 (433–2,152) |

| Return | ||||

| Mexico | United States | Mexico | 0 | 1,309 (587–2,919) |

| India | United Arab Emirates | India | 0 | 380 (170–847) |

| Russia | Ukraine | Russia | 0 | 358 (161–798) |

| Bangladesh | India | Bangladesh | 0 | 350 (157–780) |

| Transit | ||||

| Palestine | Libya | Jordan | 146 | 141 (63–314) |

| South Sudan | Sudan | Ethiopia | 82 | 73 (33–163) |

| Iraq | Syria | United States | 62 | 55 (25–123) |

| Syria | Saudi Arabia | Turkey | 41 | 42 (19–94) |

Comparison of estimates produced by the MM method and the PB method. Values in parentheses are 80% confidence intervals for PB flow estimates. POB, place of birth.

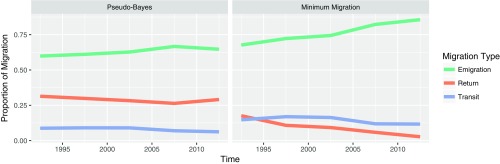

When aggregated across the globe, we find that a majority of international migration consists of emigration from the place of birth (Fig. 3), but return migration is also substantial, making up 26–31% of movements in each time period. Transit migration, however, constitutes no more than 9% of our estimated flows.

Fig. 3.

Decomposition of global migration flows into emigration (from place of birth), return migration (to place of birth), and transit. (Left) PB estimates. (Right) MM estimates.

The high volume of return migration in our estimates is an important piece of information for policy planning. Any attempt to meet a target level of population growth due to migration must consider that in-migration, which can be controlled by limiting legal and illegal means of entry, may be offset by a substantial quantity of out-migration. Moreover, intelligent policies must take into account that in- and out-migration are not independent of one another, and the relationship between the two can be complex. For example, stricter immigration policies set in place by the United States in the 1980s were responsible in part for a lower rate of return migration of Mexicans, paradoxically dampening the intended effects of the policy (18). By providing genuine estimates of emigration and return migration in all countries, we provide a quantitative basis for possible migration policy decisions in areas of the world where existing flow estimates are of poor quality or nonexistent.

Case Study: The United States/Mexico.

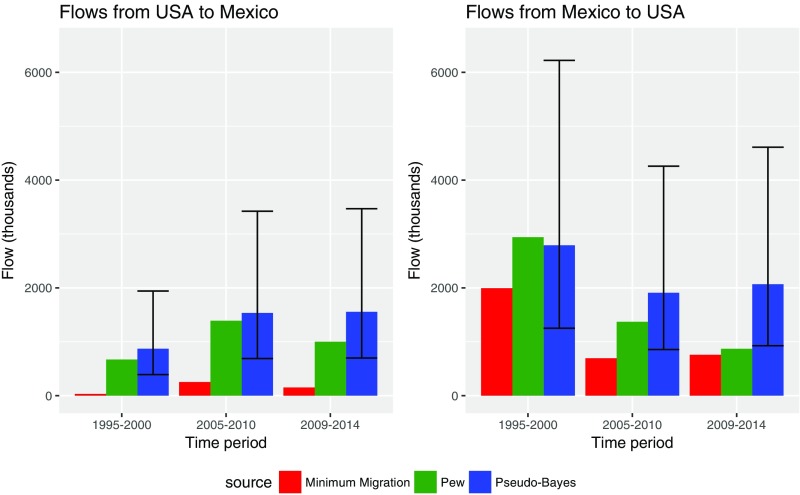

The two flows for which our estimates differ the most from the MM estimates in 2010–2015 are the two directions of flows between Mexico and the United States. Migration between the United States and Mexico is well studied, although difficult to estimate (18–20). In this section, we compare the PB and MM estimates, which are based only on stock data, with estimates from the Pew Research Center that incorporate information from demographic surveys in both the United States and Mexico (21, 22). Fig. 4, Left compares our estimates of the flows from the United States to Mexico (blue) with MM estimates (red) and the Pew estimates (green). The three sets of estimates do not quite cover identical time periods; we compare the Pew estimate for 2009–2014 with PB and MM estimates for 2010–2015. Our estimates agree approximately with the Pew estimates, while the MM estimates are lower by a factor of somewhere between 5.5 and 22.

Fig. 4.

Estimates of flows from the United States to Mexico aggregated across all places of birth (Left). Estimates of flows from Mexico to the United States for Mexican-born individuals only (Right). Estimates from Pew for 2009–2014 are genuinely for 2009–2014. PB and Abel’s (17) MM estimates for that time period use 2010–2015 instead. Confidence intervals for PB estimates are 80% confidence intervals.

Fig. 4, Right compares the Pew estimates with the PB and MM estimates of flows from Mexico to the United States. (In the Mexico to the United States direction, Pew provides estimates of flows of only Mexican-born individuals, and the corresponding PB and MM estimates are also given for Mexican-born individuals only.) In this direction, the MM estimates are consistently lower than the Pew estimates, while ours are 95–238% of the Pew estimates, and the Pew estimate is covered by our 80% confidence interval in two of three periods.

Note that flow estimates are constrained to match observed changes in stocks. In the MM estimates of the United States/Mexico flows, a large flow from Mexico to the United States is offset by a very small flow in the opposite direction, resulting in a large increase in the stock of Mexican-born individuals in the United States. Our estimates produce the same large change in stocks but do so by offsetting a very large Mexico to the United States flow with a moderate flow in the opposite direction.

Estimation of very low or zero return migration along common bilateral migration corridors is a feature of the MM estimates present along all global migration corridors and is a result of the MM assumption. In the case of the United States and Mexico, external validation data indicate that the MM estimates of low return migration represent a substantial underestimate of the true flow, and we expect that to be the case elsewhere as well. This is a systematic weakness inherent in the MM assumption—minimizing total flows does not uniformly scale down flow estimates relative to the truth but causes disproportionate underestimation in return migration flows. This systematic underestimation is not present in our estimates.

This analysis is not meant to suggest that our estimates of flows between Mexico and the United States should be trusted over those of Pew. On the contrary, since their estimates are based on demographic survey data that directly ask about migration, the Pew estimates contain detailed information not available to our method. Overall, a comparison with external estimates provides evidence that the MM estimates for the United States to Mexico flows are probably too low. Our PB estimates of the flows in both directions, although they do not entirely agree with the Pew estimates, are more in line with the magnitudes given by compiling demographic survey data.

Discussion

The migration flows that our model outputs should be interpreted as being conditional on the correctness of the inputs to our model. In particular, our flow estimates are produced under the assumption that all migrant stocks are correctly estimated. The documentation accompanying the United Nations estimates of migrant stocks (11) indicates that, in reality, these stocks are not known precisely. As is also the case with the United Nations’ estimates of net migration, many stock estimates incorporate data on refugee flows, and some stocks are imputed rather than measured. This process can and does result in high uncertainty in some stock estimates, including in some high-profile cases. For example, reliable sources suggest a large flow of Syrians into Germany during the 2010–2015 time period; the German government estimates that 137,000 Syrians migrated to Germany between January 2011 and June 2015 (23). However, the United Nations stock estimates report the total stock of Syrian-born individuals in Germany to be 51,000 individuals in mid-2010 and 53,000 individuals in mid-2015. With these stock data as inputs, there is no suggestion of a large refugee flow from Syria to Germany. Indeed, on the basis of these inputs, the MM method estimates that only 5,000 Syrian-born individuals moved from Syria to Germany during this period, while our method puts that figure at 11,000, both an order of magnitude lower than the German government’s estimate. This severe underestimation is primarily a result of poor input data. Although neither the underlying stock data nor our table of flow estimates report any measure of uncertainty, we would caution users of both to remember that such uncertainty does exist.

While the MM estimates are best treated as a lower bound on migration flows, our estimates aspire to be an order of magnitude estimate for all bilateral migration flows. Our method is not intended to supplant estimates of migration flows that are available from targeted data sources (e.g., from administrative records of entries and exits or from asylum applications). The strength of our method is that it produces estimates of flows between all pairs of countries, including the many flows for which no primary data sources exist. In contrast to the lower bound-based MM estimates, which are often exactly zero for such flows, our estimates should all be of a plausible order of magnitude.

Although the PB estimator performs well as a point estimator for migration flows, it lacks quantified uncertainty in those estimates. A natural way to obtain confidence intervals for flows would be to take a fully Bayesian approach, estimating posterior distributions on the entries in flow tables conditional on the known table margins and a prior distribution on table entries. In principle, Bayesian analysis on contingency tables with known margins is possible (24, 25). This approach would entail sampling from the posterior distribution via Markov Chain Monte Carlo updating of table entries. However, in each time period, we are trying to estimate a total of 200 tables, each of dimension . Given the relatively high dimension of the problem, it is not clear whether the sampling procedure would be prohibitively costly in terms of computational power.

Methodologically, our approach shares some common traits with Bayes linear methods (26)—both are Bayesian approaches with a primary focus on expectations rather than full distributions, and both alleviate the issue of eliciting priors by imposing linear structure on prior means. It may be possible to further refine the uncertainty quantification in our estimates by explicitly formulating our estimates in the Bayes linear framework. Although we are able to provide an estimate of uncertainty for each individual flow marginally, estimating uncertainty in aggregated flows (e.g., the flows between regions pictured in Fig. 2) requires a better understanding of correlations between flows, which a Bayes linear approach could provide.

Recent work on migration flow estimation by Dennett (27) depends on the same observation that flows are closely associated with existing migrant stocks, which forms the basis of our method, and similarly uses the IMEM estimates as a best-available standard for comparison. However, Dennett (27) only applies his method to European flows, as it relies on a preexisting estimate of the total migrant flow within each time period, which is not available globally.

Our model incorporates a weighting factor, , which controls the balance between two extremal assumptions about migration flows. One limitation of our model is that this weight must be empirically determined based on existing flow estimates, and those flow estimates have limited coverage. In particular, high-quality estimates exist for flows to and from developed countries but not for so-called south–south flows between developing countries. While we did find that optimal values of differed very little between the flow types that we had available, south–south flows may be systematically different from flows to or from more developed countries. Unfortunately, it is not clear whether we should expect that the MM assumption will be more suitable or less suitable for south–south flows.

Our estimates of migration flows are broken down by place of birth only. In principle, the same procedure could be applied to flows that are broken down by other characteristics in addition to or instead of birthplace. At a global level, more detailed breakdowns of migrant stocks by other characteristics are not generally available for all countries. One exception is breakdowns by sex, which have been combined with the MM method to produce migration estimates that retain the structural zeroes inherent to the method (28). However, the same technique developed here may be useful in producing estimates of either international migration flows broken down by other characteristics for a subset of the world’s countries or disaggregated subnational migration flows.

Materials and Methods

Data.

To produce estimates of migrant flows between all pairs of countries, our method requires estimates of migrant stocks by place of birth as well as total births, deaths, and net migration within each time period of interest. We source all of these estimates from the United Nations. The United Nation estimates of migrant stocks are compiled from various national sources for all countries at 5-y intervals from 1990 to 2015 (11). [A second set of migrant stock estimates is available from the World Bank at 10-y intervals from 1960 to 2000 (29), but we use the United Nations data for our analysis, because they are more recent and fine grained in time.] The United Nations estimates of births, deaths, and population for all countries are given in the World Population Prospects (12).

Our method is tuned to minimize error against flow estimates for a subset of countries in which reasonable quality estimates of migration flows exist. These external data serve as a “bronze standard” (somewhat inferior to “gold standard” data but still of sufficient quality for validation.) These we draw from two sources. The first source is the flow estimates produced by the IMEM project (7). These consist of estimated total flows between 31 pairs of European countries and cover the years from 2002 to 2008 on an annual basis. The second source is the OECD, which compiles estimates of annual migration flows to and from 34 of the current 35 OECD member states. Although these are subject to the undercounting issues, which the IMEM flows adjust for, they are nonetheless valuable in that they provide a more detailed picture of flows to and from the developed world and have fairly low levels of data missingness. At least two other fairly extensive sets of migration flow estimates are available. The United Nations publishes annual migration flow estimates covering several decades (30) as does the Determinants of International Migration project (31). In both cases, we have chosen not to use these data, because the level of completeness varies greatly between counties as well as over time, and this data missingness is a potential source of bias.

Our choice of datasets was motivated by selecting only data for which missingness could plausibly be treated as completely random. In practice, this may be exchanging one kind of bias for another, as we have no way of determining whether the bias introduced by nonrandom missingness would be outweighed by other systematic errors in the estimates that we selected. With better integration and harmonization of the multiple data sources, there may be room to improve our estimates.

Producing PB Estimates.

At the finest level of granularity, the quantities of interest are the unknown flow tables defined by

| [1] |

where the entry is a flow from country to country of individuals with place of birth during time period . Note that only the off-diagonal elements of represent genuine migration flows. The diagonal elements represent individuals who resided in country both at the beginning and at the end of the time period—that is, stayers rather than movers.

A key observation is that, in the absence of births and deaths, the row and column sums of are known. Each row sum, , gives the total population of individuals with place of birth residing in country at time . That is, the row sums are migrant stocks at time , which we will denote by . Likewise, the column sums, , give the population of individuals with place of birth residing in country at time —that is, the stocks .

In our results, we adopt the treatment of births and deaths introduced in ref. 17 without modification. Under this method, births in country are assumed to increase the value of —that is, the stock of individuals born in country and residing in country at the end of the time period of interest. Deaths in country are assumed to occur proportionally to the place of birth composition in country and decrease the relevant stocks. A more refined apportionment of deaths by place of birth might also take into account the age structure and/or age-specific mortality rates of migrant populations, but this additional information is only rarely available. Additional adjustments to the stocks are made to ensure that the changes in stocks agree with the known net migration counts while maintaining approximate agreement with the assumed births and deaths.

The MM method amounts to fitting a separate Poisson log-linear model to each table, . The model assumes that table elements are independently drawn from Poisson distributions so that

| [2] |

Furthermore, the Poisson means are assumed to follow a quasiindependence structure:

| [3] |

where is a prespecified offset term and the terms are constrained so that unless . This condition on the terms says that the Poisson means for the diagonal elements of each table are unconstrained, while the off-diagonal elements follow an independence structure. Conceptually, this constraint can be viewed as a statement that moving is different from staying.

Sufficient statistics for inference on the Poisson model parameters are given by the known row margins (i.e., stocks at time ), the known column margins (i.e., stocks at time ), and the unknown diagonal entries . After the diagonal values are fixed, the maximum likelihood estimates for the parameter vectors and can be found via iterated proportional fitting (32, 33). One implementation of the iterated proportional fitting procedure can be found in the migest R package (34).

Our migration flow estimates are a PB estimator for , which has the same row and column totals as the MM estimator but lacks the problematic structural zeroes. The PB estimator is produced using the following procedure.

-

i)

Using data on stocks, births, and deaths, find the MM estimate for each flow matrix . These estimates should include adjustments of stocks for births, deaths, and agreement with country-specific net migration totals.

-

ii)

Compute the row and column totals of to extract adjusted stock estimates and .

-

iii)Construct a second set of estimates with independence structure. Elements of are given by

Note that this is the matrix of maximum likelihood estimates from a Poisson model on migration flows, where is conditional on the given row and column totals with no additional assumptions made about the diagonal.[4] -

iv)Construct the PB estimator as a convex combination of and :

for some value .[5]

For any choice of , the estimator is a valid PB estimator of the unknown table entries. (SI Appendix has mathematical details.) One way to think of the PB estimator is as smoothing toward a matrix with smaller diagonal and fewer zero entries. This form of smoothing is a common approach to estimation of cell probabilities in contingency tables with many observed zeroes (35). By construction, the PB estimates of migration flows maintain consistency with the observed changes in stocks while also allowing for large cross-flows concentrated in locations with large existing migrant populations. We find that the optimal smoothing parameter retains the property that the number of nonmovers is large, reflecting the generally low propensity for and high barriers to international migration.

We note several advantageous properties of this estimator. First, row and column sums of each table will be identical to those of the MM estimator, , by construction. Second, this estimator lacks the structural zeroes of . Before rounding to integer values, estimated flows will be nonzero whenever countries and both have nonzero populations of individuals with place of birth . The final estimate may round down to zero but only when those populations are small, in which case migration flows are indeed likely to be small. Third, for values of close to one, the diagonal entries of will be nearly maximized but not exactly maximized. This allows us to retain the property that the number of nonmovers is large. (All results presented here are based on a fitted value of .) Finally, after is computed, finding the PB estimator requires very little additional computation.

Additional details about offset terms, selection of an optimal value of , and derivation of confidence intervals are provided in SI Appendix.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Charles Hirschman for discussions. This work was supported by NIH Grants R01 HD54511 and R01 HD70936 and the Center for Advanced Study in the Behavioral Sciences at Stanford University.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*Net migration into a country in a given period is the number of in-migrants from all origin locations minus the number of out-migrants to all destinations in the period. Migration flows refer to the number of people who reside in country at the start of a time period and country at the end of a time period. (Our analysis uses 5-y time periods unless otherwise noted.) Migrant stocks here refer to the number of people living in one country at a given time who were born in another specified country.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1722334116/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Azose JJ, Ševčíková H, Raftery AE. Probabilistic population projections with migration uncertainty. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:6460–6465. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1606119113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bilsborrow RE. International Migration Statistics: Guidelines for Improving Data Collection Systems. International Labour Organization; Geneva: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ratha D, Shaw W. South-South Migration and Remittances. World Bank Publications; Washington, DC: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Massey DS, Capoferro C. Measuring undocumented migration. Int Migr Rev. 2006;38:1075–1102. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zlotnik H. Measuring international migration: Theory and practice. Int Migr Rev. 1987;21:v–xii. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development . OECD International Migration Database. Organization for Economic Co-Operation and Development; Paris: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Raymer J, Wiśniowski A, Forster JJ, Smith PW, Bijak J. Integrated modeling of European migration. J Am Stat Assoc. 2013;108:801–819. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Abel GJ. Estimating global migration flow tables using place of birth data. Demographic Res. 2013;28:505–546. [Google Scholar]

- 9.De Beer J, Raymer J, Van der Erf R, Van Wissen L. Overcoming the problems of inconsistent international migration data: A new method applied to flows in Europe. Eur J Popul. 2010;26:459–481. doi: 10.1007/s10680-010-9220-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Raymer J, de Beer J, van der Erf R. Putting the pieces of the puzzle together: Age and sex-specific estimates of migration amongst countries in the EU/EFTA, 2002–2007. Eur J Popul. 2011;27:185–215. [Google Scholar]

- 11.United Nations . International Migrant Stock: The 2015 Revision. United Nations; New York: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 12.United Nations . World Population Prospects: The 2015 Revision. United Nations; New York: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kitsul P, Philipov D. The one year/five year migration problem. In: Rogers A, editor. Advances in Multiregional Demography. International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis; Laxenburg, Austria: 1981. pp. 1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Newbold KB. Spatial scale, return and onward migration, and the Long-Boertlein index of repeat migration. Pap Reg Sci. 2005;84:281–290. doi: 10.1111/j.1435-5597.1997.tb00688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rees PH. The measurement of migration, from census data and other sources. Environ Plann A. 1977;9:247–272. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu Z, Gu L, Eils R, Schlesner M, Brors B. circlize implements and enhances circular visualization in R. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2811–2812. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abel GJ, Sander N. Quantifying global international migration flows. Science. 2014;343:1520–1522. doi: 10.1126/science.1248676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Durand J, Massey DS, Parrado EA. The new era of Mexican migration to the United States. J Am Hist. 1999;86:518–536. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hanson GH. Illegal migration from Mexico to the United States. J Econ Lit. 2006;44:869–924. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Massey DS, Espinosa KE. What’s driving Mexico-US migration? A theoretical, empirical, and policy analysis. Am J Sociol. 1997;102:939–999. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzalez-Barrera A. 2015. More Mexicans leaving than coming to the US (Pew Research Center, Washington, DC), Technical Report.

- 22.Passel J, Cohn D, Gonzalez-Barrera A. 2012. Net migration from Mexico falls to zero—and perhaps less (Pew Research Center, Washington, DC), Technical Report.

- 23.Deutscher Bundestag 2015 Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 18/5799 Aufnahme von syrischen Flüchtlingen zum Stand Mitte 2015. Available at dip21.bundestag.de/dip21/btd/18/057/1805799.pdf. Accessed December 9, 2018.

- 24.Dobra A, Tebaldi C, West M. Data augmentation in multi-way contingency tables with fixed marginal totals. J Stat Plan Inference. 2006;136:355–372. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Forster JJ. Bayesian inference for Poisson and multinomial log-linear models. Stat Methodol. 2010;7:210–224. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goldstein M, Wooff D. Bayes Linear Statistics: Theory and Methods. Vol 716 John Wiley & Sons; Chichester, UK: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dennett A. Estimating an annual time series of global migration flows—An alternative methodology for using migrant stock data. In: Wilson AG, editor. Global Dynamics: Approaches from Complexity Science. Wiley Online Library; Chichester, UK: 2016. pp. 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abel GJ. Estimates of global bilateral migration flows by gender between 1960 and 2015. Int Migr Rev. 2018;52:809–852. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Özden Ç, Parsons CR, Schiff M, Walmsley TL. Where on earth is everybody? The evolution of global bilateral migration 1960–2000. World Bank Econ Rev. 2011;25:12–56. [Google Scholar]

- 30.United Nations . International Migration Flows to and from Selected Countries: The 2015 Revision. United Nations; New York: 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vezzoli S, Villares-Varela M, De Haas H. 2014 Uncovering international migration flow data: Insights from the DEMIG databases (International Migration Institute, University of Oxford, Oxford). Available at https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/401081/. Accessed December 9, 2018.

- 32.Bishop YM, Fienberg SE, Holland PW. Discrete Multivariate Analysis: Theory and Practice. MIT Press; New York: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Willekens F. Modeling approaches to the indirect estimation of migration flows: From entropy to EM. Math Popul Stud. 1999;7:239–278. doi: 10.1080/08898489909525459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abel GJ. 2013 migest: Useful R Code for the Estimation of Migration. The CRAN Project. Available at https://cran.r-project.org/package=migest. Accessed December 12, 2014.

- 35.Fienberg SE, Holland PW. Simultaneous estimation of multinomial cell probabilities. J Am Stat Assoc. 1973;68:683–691. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.