Abstract

Although genomes are defined by their sequence, the linear arrangement of nucleotides is only their most basic feature. A fundamental property of genomes is their topological organization in three-dimensional space in the intact cell nucleus. The application of imaging methods and genome-wide biochemical approaches, combined with functional data, is revealing the precise nature of genome topology and its regulatory functions in gene expression and genome maintenance. The emerging picture is one of extensive self-enforcing feedback between activity and spatial organization of the genome, suggestive of a self-organizing and self-perpetuating system that uses epigenetic dynamics to regulate genome function in response to regulatory cues and to propagate cell-fate memory.

The genome is arguably one of the most critical cellular structures. Yet, the discovery of genome organization and function has taken a path opposite to that of many cellular structures. Most cellular organelles were first described morphologically using microscopy studies, and their functions were uncovered subsequently, often pains-takingly, using biochemical and molecular approaches. The study of the genome followed the reverse path, with its most prominent functions such as transcription, replication, DNA repair and mutagenesis being the subject of intense research efforts for decades, and its three-dimensional (3D) organization and the relevance of its spatial topology to nuclear processes just beginning to be unraveled.

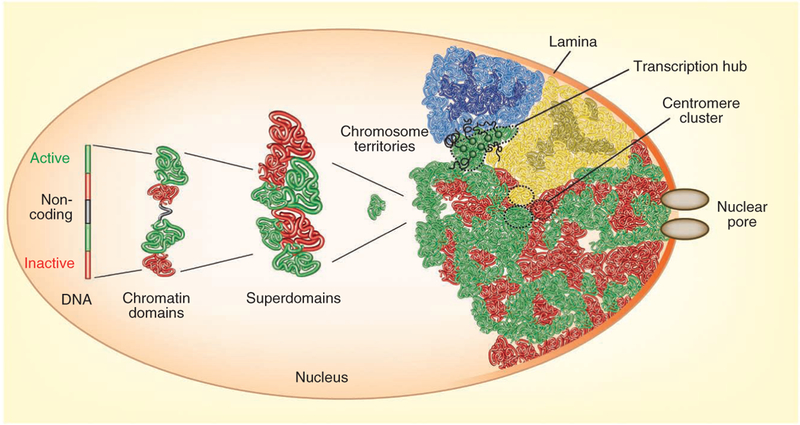

Traditional studies on genome organization were dominated by electron and light microscopy approaches to describe, at increasingly higher resolution, the arrangement of genes and chromosomes in the cell nucleus. These efforts led to the fundamental realization that genomes are spatially arranged at several, hierarchical levels in the 3D space of the cell nucleus, starting with the folding of the chromatin fiber into higher-order structures, the formation of loops over a wide range of genomic distances and the formation of chromosome domains, culminating in their aggregation to form chromosome territories (Fig. 1). Beyond that, it was recognized that chromosomes are nonrandomly arranged in the nuclear space, with many genes occupying preferred positions relative to other regions in the genome or to nuclear structures such as the nuclear envelope, domains of heterochromatin or nuclear bodies1–3 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1.

A global view of the cell nucleus. Chromatin domain folding is determined by transcriptional activity of genome regions. Boundaries form at the interface of active and inactive parts of the genome. Higher-order domains of similar activity status cluster to form chromatin domains, which assemble into chromosome territories. Repressive regions of chromosomes tend to contact other repressive regions on the same chromosome arm, whereas active domains are more exposed on the outside of chromosome territories and have a higher chance of contacting active domains on the other chromosome arm and on other chromosomes19,20, giving rise to topological ‘superdomains’ composed of multiple, functionally similar genome domains. The location of territories is constrained by their association with the nuclear periphery, transcription hubs, nuclear bodies and centromere clusters

These insights from imaging approaches have been confirmed by recently developed methods to biochemically probe chromatin interactions to generate genome-wide physical maps of the genome’s landscape4,5. The importance of these so-called chromosome conformation capture (3C) technologies is twofold. They provide quantitative, high-resolution maps of the contacts established in a chromatin region of interest, and they enable probing of genome interactions genome-wide rather than locus by locus, as is done using imaging approaches. The combination of these biochemical methods and microscopy promises to uncover how genome organization, at all levels, relates to function. We are at the very beginning of this new era of genome biology. In this Review we will discuss emerging themes of how genome organization influences gene function.

Principles of genome organization

The fundamental cell biological unit of genomes is the chromosome. Clever fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) experiments in the 1980s showed that in mammalian cells the genetic material of an individual chromosome occupies a spatially limited territory, typically roughly spherical in shape and 2–4 μm in diameter1. These chromosome territories are tightly packed in the nucleus, and they abut at their borders to create a continuous body of chromatin (Fig. 1). Whereas in higher eukaryotes chromosome territories intermingle only at their peripheries6, in the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae chromosome territories are spatially less well defined and intermix to a much greater extent, most probably reflecting the globally more decondensed nature of yeast chromatin, its lack of large heterochromatin domains, and possibly the smaller size of the genome, which might require less spatial organization to ensure functionality7.

The fact that each chromosome exists as a spatially confined territory raises the question of whether chromosome territories, and consequently the genes they carry, are arranged randomly in the 3D nucleus or occupy preferred positions2. FISH analysis of chromosomes and of many genes demonstrates that most genetic elements occupy preferred nonrandom positions. Positioning patterns of genes and chromosomes differ between cell types, and they undergo changes during physiological processes such as differentiation, development and aging (Boxes 1 and 2), and in pathological situations. Analyses using 3C technology have confirmed the nonrandomness of genome organization via genome-wide mapping of preferential interaction patterns between chromosomes and genes in many tissues8. In line with this view, live-cell imaging demonstrates that the extent of motion of genes and chromosomes during interphase is limited9, thus generating relatively stable, steady-state large-scale genome topology.

Box 1. Three-dimensional genome organization during differentiation and development.

Genome organization undergoes dramatic changes during differentiation and development. Effects of genome organization are particularly prominent In embryonic stem (ES) cells. The genome landscape of ES cells is unique in that it is characterized by an abundance of active chromatin marks and reduced levels of repressive ones117,118. ES cells have less compacted heterochromatin domains, and their centromeric regions are decondensed117,119,120. DNase hypersensitivity analysis suggests globally more accessible and open chromatin. The altered chromatin architecture is accompanied by a loss of binding of several architectural chromatin proteins, including heterochromatin protein HP1 and high-mobility group (HMG) proteins117, and increased amounts of chromatin remodelers and modifiers121,122. As ES cells differentiate, many of ES cell-specific chromatin hallmarks rapidly disappear. Roughly the reverse processes occur during reprogramming of differentiated cells into induced pluripotent stem cells123. These observations point to a model in which chromatin structure is essential in establishing pluripotency by maintaining the genome in an open, readily accessible state, allowing for maximum plasticity.

In mouse embryogenesis, the maternal and paternal pronuclei are not symmetric: the paternal pronucleus lacks typical heterochromatin marks but contains Polycomb proteins that are absent from the maternal heterochromatin124. In Drosophila melanogaster, the cell cycle slows down as differentiation processes unfold during developmental progression. This is accompanied by a general decrease in nuclear volume, a progressive condensation of chromatin and a decrease in chromatin motion33. A strong reduction of Polycomb-dependent chromatin motion, concomitant with an increase in the residence time of Polycomb proteins on their target chromatin, parallels developmental progression, suggesting that a decrease in chromatin dynamics is required to stabilize gene silencing33, a process reminiscent of what happens during ES cell differentiation. More direct evidence for a role of three-dimensional chromosome organization in the developmental regulation of gene expression comes from studies in Caenorhabditis elegans, where movement of tissue-specific genes in the nuclear interior that is developmentally programmed and is dependent on histone methyltransferases MET-2 and SET-35 has been described82,125.

BOX 2. The aging three-dimensional genome.

Various features of chromatin and chromosomes change during aging. Cells from aged Individuals often exhibit reduced areas of heterochromatin, loss of repressive histone marks, altered composition of core histones and histone variants, and appearance of nucleosome-free regions126–129. It remains unclear how these changes are brought about. Analysis of the corresponding changes in the premature aging disorder Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome has pointed to a role of the NURD chromatin remodeling complex in these aging-related chromatin changes130,131. In addition, aged yeast and human cells exhibit a considerable decline in the amount of core histones H3 and H2A and a concordant decrease in histone H3 occupancy131. The reduced occupancy may be brought about by age-associated decline in the activity of some of the histone chaperones that are required to deposit nucleosomes after replication132,133. The altered nucleosome occupancy may have multiple detrimental consequences. One possibility is suggested by the fact that telomeres are particularly sensitive to nucleosome assembly defects133. Another possibility is that the altered chromatin structure makes chromatin globally more prone to DNA damage134, another hallmark of aged cells. Activation of DNA damage responses in aged cells may promote global chromatin changes, as DNA damage triggers redistribution of chromatin proteins such as the histone deacetylase SIRT1, leading to aberrant histone modification patterns, misregulation of aging-related genes and changes in higher-order chromatin structure135, establishing a self-enforcing feedback loop between chromatin structure and its function.

From chromatin to chromatin domains.

The high degree of structural and functional organization of genomic chromatin extends to the subchromosomal level. Recent years have seen the generation of detailed maps of the distribution of various chromatin-binding proteins, histone marks and DNA methylation in different species and cell types. Perhaps one of the most interesting observations from these efforts is that chromosome territories are not generated by homogeneous folding of the underlying chromatin but instead comprise discrete chromatin domains (Fig. 1). The domain size depends on the chromosomal region, the cell type and the species, spanning few tens of kilobases to several megabases (averaging ~100 kb in flies and ~1 Mb in humans)10–16.

Various studies report somewhat different classifications of chromatin types, mostly depending on the parameters used in the computational analysis, but the general consensus is that there are only a few types of repressive chromatin. The repressive domains are Polycomb- bound euchromatin, heterochromatin and a chromatin state that has no strong enrichment for any of the specific factors or marks used for mapping11,12,14. In contrast, there are various types of active or open chromatin, and it has proven more difficult to rigorously classify them, probably because the classification depends on the number of factors that are used for mapping. However, at least four types of open chromatin can be distinguished with some certainty, encompassing ‘enhancers’, ‘promoters’, ‘transcribed regions’ and ‘regions bound by chromatin insulator proteins’15.

An important feature of chromatin domains is that not all genes within the domain have the same transcriptional response. Some open chromatin domains may contain nontranscribed genes and some repressive domains may encompass transcribed regions, suggesting that chromatin domains can accommodate a certain degree of individual gene regulatory freedom16,17. Nevertheless, the overall gestalt of a given chromatin domain exerts its influence, as demonstrated by the fact that insertion of transgenes in different chromatin domains affects expression of a reporter gene. Therefore, domains build more or less favorable chromatin environments for gene expression but do not fully determine gene activity17.

Topologically associated domains.

Recent investigations of the 3D folding of the fly, mouse and human genomes generalized the concept of chromatin domains and revealed that domains, as mapped by epigenome profiling, correspond to physical genome domains18–21. These topologically associated domains are characterized by sharp boundaries that correspond to binding sites for CTCF and other chromatin insulator-binding proteins as well as to active transcriptional start sites18–20. The partitioning of the genome into domains raises the question of whether long-distance interactions between them can occur and, more importantly, whether such interactions contribute to the folding of a chromosome territory (Fig. 1). Systematic analysis of Drosophila melanogaster genome maps generated using the genome conformation capture-related Hi-C technique revealed that both active and inactive domains undergo long-range interactions, with repressed domains predominantly interacting with other inactive domains on the same chromosome arm, but active domains interacting with active domains on the same chromosome arm, on different chromosome arms or on other chromosomes20. Morphological analysis supports this notion22,23. These observations suggest that repressed domains may form the core, or the skeleton, of the chromosome territory, whereas active domains may extend out from the territory to contact other active regions on the same or on different chromosomes (Fig. 1).

Mechanisms of chromatin domain formation.

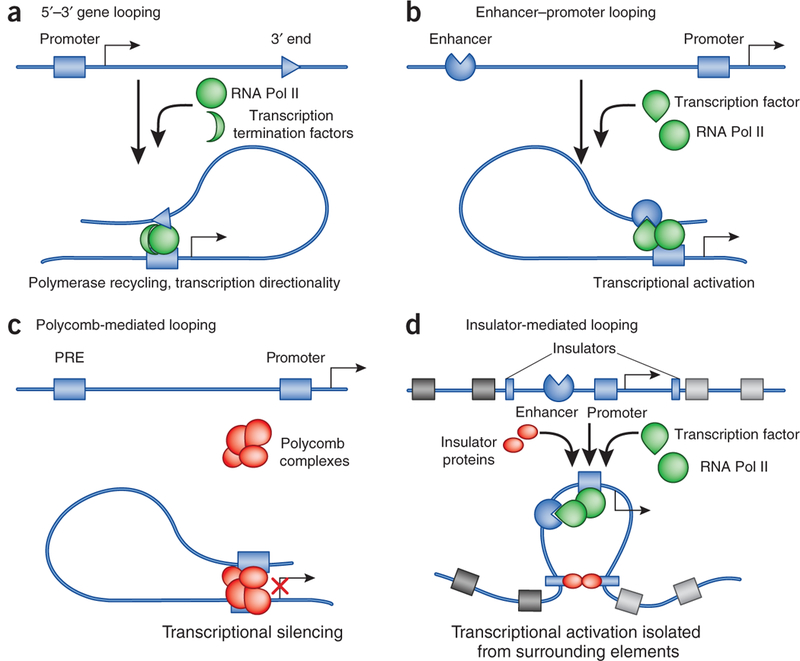

The pervasive tendency of chromatin to engage in contacts with surrounding chromatin fibers may be the basis of higher-order chromosome organization. Genome-wide 3C technologies have shown that the existence of physical chromosomal domains reflecting defined epigenome compositions is a universal principle in higher eukaryotic cells, hinting at a common molecular mechanism for their formation. This mechanism may be represented by the propensity of chromatin to establish contacts in the form of loops (Fig. 2). Looping extends well beyond specific elements, as shown by 3C experiments where the quantitatively dominant component in chromatin contacts is represented by loops formed among surrounding chromatin24. Notably, looping is not promiscuous. High-resolution circular chromosome conformation capture (4C) analysis of Hox clusters in embryonic mouse tissues where different genes are active shows that active and repressive chromatin contacts are spatially segregated in the developing mouse embryo25. The separation between active chromatin, defined by the presence of the ‘active’ H3K4me3 histone mark, and repressed chromatin, containing H3K27me3, in this case is unlikely to involve insulator binding factors as the two chromatin compartments evolve progressively in space and time in the mouse embryo25. In other instances, CTCF, cohesin and other insulator factors may be involved in domain separation18,20. Therefore, the general ability of chromatin to form transient contacts that are increasingly likely for smaller distances along the same chromosome, the added specificity by specific chromatin factors, and the separation between types of loops, such as those involving active and repressive chromatin, may be general principles that serve to organize the chromosome into topologically associated domains and ultimately into chromosome territories.

Figure 2.

Four types of transcription regulatory chromatin loops. (a) Intragenic loops joining the 5’ and 3’ end of genes may allow recycling of RNA Pol II and facilitate maintenance of transcriptional directionality. (b) Enhancer- promoter loops—mediated by sequence-specific transcription factors, and possibly assisted by noncoding RNAs or by general DNA binding factors such as CTCF and cohesin—lead to transcriptional activation. (c) Loops between Polycomb-bound regions (PREs) and promoters prevent RNA Pol II recruitment and/or impair transcriptional elongation of promoter-bound RNA polymerases. (d) Insulator-mediated loops may segregate individual loci containing the coding part of the gene and its regulatory regions from the surrounding genome landscape with other regulatory elements.

Three-dimensional genomic location.

At an even higher level, chromosomes do not occupy random positions in the nuclear space. For instance, gene-rich and transcriptionally more active chromosomes tend to be located in the nuclear interior, whereas gene-poor and less active chromosomes are closer to the nuclear periphery1. The mechanisms that determine the arrangement of chromosomes and the position of genes in the nucleus are poorly characterized. In S. cerevisiae, the nonrandom organization of chromosomes and gene loci can be reproduced accurately in silico in a simple model in which chromatin fibers can move freely as polymer chains and are merely constrained by their tethering to the nuclear periphery via telomeres, the association of centromeres with each other and the clustering of ribosomal genes in the nucleolus26. The fact that no additional constraints, such as specific DNA-recognition factors, are required to reproduce the spatial arrangement of genomes suggests that the spatial organization of chromosomes and DNA contacts in yeast is dictated mainly by genomic location, chromosome lengths and genome-wide transcriptional activity26,27.

There is reason to believe that similar principles of constraining the 3D location of a genomic site apply to higher eukaryotes. Centromeres from multiple chromosomes often congregate in the nuclear space to form large heterochromatin domains, and ribosomal genes aggregate in the nucleolus, thus constraining the location of a given chromosome2 (Fig. 1). But additional mechanisms of constraint appear to apply in higher eukaryotes. Mammalian and fly genomes contain extensive genome regions that physically associate with the nuclear periphery, where these regions interact with the nuclear lamina, a proteinaceous network that underlies the nuclear membrane28,29 (Fig. 1). In mammalian cells, these lamina-associated domains are 0.1–10 Mb in size and are present in multiple copies on every chromosome, allowing for their tethering to the nuclear periphery. In higher organisms, the location of chromosomes and genes is constrained by their physical association with many nuclear bodies. For example, a limited set of genome sites interacts with the promyelocytic leukemia body or with Cajal bodies30,31. In D. melanogaster, genome regions containing Polycomb response elements cluster in Polycomb bodies, where they are repressed32,33. In addition, the arrangement of genome regions may also be constrained by clustering of active regions, such as the association of co-regulated genes in transcription factories34 (Fig. 1).

Stochastic, yet conserved, genome topology.

A critically important feature of all aspects of higher-order spatial genome organization is its probabilistic nature. Single-cell FISH analysis of sets of genes and entire chromosomes shows that no two cells exhibit exactly the same genome organization35. Computational analysis of genome-wide interaction data indicates the existence of multiple subpopulations of cells, demonstrating that the average interaction maps generated using population-based methods are an ensemble of many different genome landscapes36. In line with that interpretation, photobleaching experiments have demonstrated that gene and chromosome positions are semiconserved through mitosis such that, although the position of a given gene or chromosome may change in an indi-vidual cell, the overall distribution pattern in the population remains the same37. Single-cell 3C methodology will provide a more complete view of the stochastic nature of genome organization.

Transcription and gene regulation

Genome topology has emerged as a key player in all genome functions. Although a contribution of local genome looping in transcription has long been appreciated, recent observations have revealed the importance of long-range interactions, and genome-wide studies have uncovered the universal nature of such regulatory genome topology interactions in gene regulation. Several types of chromosomal interactions, either in the form of loops between sequences on the same chromosomes or interchromosomal interactions, have emerged as key mechanisms in gene regulation.

Intrachromosomal looping.

There are four types of loops that have direct functional consequences for transcription (reviewed in ref. 38). The first type joins the 5’ end of transcribed genes with the transcription termination site (Fig. 2a). Such loops, first observed in yeast39, are also observed at certain mammalian promoters40. This class of loops may allow efficient recycling of the RNA polymerase II (Pol II) from its termination site back onto the promoter. The presence of such 5’-end loops correlates with the ability to rapidly reactivate gene transcription after a transient period of repression, suggesting that a looped structure establishes a short-term memory of the previous transcriptionally active state for these genes41. Another function of these loops is to enhance transcription directionality of protein- coding genes42.

The second type of regulatory loop brings distant enhancers in contact with promoters (Fig. 2b). The β-globin locus control region (LCR) was the first of many examples of this type of loop43. Since the characterization of interactions between the LCR and promoters in the β-globin locus, many other cases of enhancer-promoter interaction have been documented, and in several cases gene regulatory switches involve changes in loop architecture, bringing different enhancers in contact with a target promoter38. In addition to proteins, noncoding RNAs may participate in the formation of loops, in some cases by yet unknown mechanisms44,45. Loop formation is mechanistically critical in the induction of transcription, as demonstrated by targeting of the transcription cofactor Ldbl to the β-globin LCR by fusing it to an artificial zinc finger, in a GATA1 null proerythroblast cell line, which is normally incapable of inducing looping between the β-globin LCR and promoter46. Under these circumstances, Ldbl tethering restores looping, Pol II phosphorylation and transcriptional activation46. Enhancer-promoter chromatin loops are also responsible for removing repressive chromatin marks for transcriptional activation. In a ‘humanized’ mouse model in which the human α-globin locus was inserted either in its wild-type form or containing a deletion in an enhancer located 60 kb away from the promoter, the enhancer can clear Polycomb proteins from the CpG island located in the α-globin promoter region47. As of today, it is not known how many of the chromatin contacts are used for enhancer-mediated gene activation. However, a recent study has expanded this field, showing that not only enhancers but also promoters can engage in mutual interactions48. These interactions are likely to have functional roles because they frequently occur in co-regulated genes and, in transgenic settings, distally located promoters can potentiate the transcriptional output of proximal promoters48.

A third type of looped transcriptional regulation is Polycomb- dependent repression via looping of regions containing Polycomb response elements to reach distal gene promoters (Fig. 2c). This type of looping interactions has been described in mammalian cells49,50 as well as in D. melanogaster51. Although the net result of Polycomb- dependent looping interactions is gene silencing instead of activation, the molecular principles guiding looping interactions might not be fundamentally different and may involve protein-protein interactions among Polycomb proteins and promoter-associated factors52–54 as well as among proteins that bind chromatin insulators juxtaposed to Polycomb response elements55,56. Other repressive looped interactions have been characterized that involve other transcriptional regulators57–59. Whether or not Polycomb components are linked to these phenomena remains to be investigated, but the available evidence suggests that repressive looping interactions may follow similar mechanisms as their activating counterparts, the main difference being the function of the molecules brought in contact by the loop.

A fourth type of looping interactions involves insulator-binding proteins (Fig. 2d), such as CTCF, cohesin and insulator-binding proteins that are present in insects but not in mammals60. Insulators have been suggested to be critical elements that can prevent enhancers from activating promoters when located between them. As such, they may isolate gene domains from surrounding genomic regions that may illegitimately activate or repress their transcription. Indeed, topological chro - matin domains have been shown to have borders at insulator-protein binding sites in D. melanogaster and in mammals19,20. However, recent chromosome conformation capture carbon copy (5C) analysis of chromatin contacts made by promoters showed that in human cells many sites bound by CTCF are skipped by enhancers, making contacts with distal promoters61. Moreover, knockdown of insulator-binding proteins did not induce dramatic chromatin changes or perturbations of gene expression, suggesting that if insulator-binding proteins are involved in genome partitioning, they do so together with other, yet-unknown factors62,63. Alternatively, not all insulator-protein binding sites are used to set chromatin boundaries: some may be nonfunctional, others may be involved in gene activation or silencing and only a subset might be actually used for genome partitioning. Future molecular genetic and genomics studies will be needed to resolve this point.

Interchromosomal contacts.

Whereas loops lead to juxtaposition of genome regions on the same chromosome, functional interactions between distinct chromosomes are also emerging as prominent functional regulators. These interactions may involve whole chromosomes, such as in the case of X-chromosome inactivation64–66, where X chromosomes pair during a transient period during embryonic stem (ES) cell differentiation. In this case, a critical regulatory noncoding RNA, called Tsix, is biallelically expressed before pairing but becomes monoallelic shortly thereafter, suggesting that pairing events break the symmetry between the two X chromosomes and may thus participate in the initial stages of random inactivation of one of the two copies64. Interchromosomal contacts are also widespread among individual monoallelically expressed genes such as at imprinted loci, although the precise molecular role of pairing is not known67–69. Many long-distance contacts among active genes on the same or different chromosomes have also been detected in mouse erythroid cells, some of which might be mediated by the same transcription factors70. Along the same lines, arrays of ribosomal RNA genes are clustered in transcription factories in the nucleolus71. In some cases, long-range interactions in trans may favor coactivation of the contacting genes72. Other examples of interchromosomal interactions with apparent regulatory potential are the association of the T helper cell 2 LCR on chromosome 11 with interferon- Y regulatory regions on chromosome 10 (ref. 73), interaction of the regulatory H element with active olfactory receptor genes on distinct chromosomes74, silent olfactory receptor gene clustering at heterochromatic regions75, and the association of NF-кB-responsive interferon-β enhancer in trans to the interferon-β gene76.

Spatial positioning of genes.

Beyond contacts among genes, their position in the 3D nuclear space may also have a role in their regulation. The extent of this effect, however, remains somewhat unclear. On the one hand, although the distribution of most genes is nonrandom when a population of cells is considered, single-cell analysis reveals that an individual allele may occupy any position in a given nucleus, without an apparent effect on the gene’s activity35. This observation quite clearly demonstrates that the spatial position of an individual locus is not an essential determinant of its activity. On the other hand, the observation that genes of different functional status appear to associate with distinct nuclear features (for example, lamina, heterochromatin domains) argues for a role of position in gene activity. It remains to be seen whether these positioning patterns are a cause or a consequence of gene activity. Identification of the molecular machinery that mediates positioning should provide answers to this important question.

A special case of a spatial positioning effect is the nuclear periphery. In most cell types, the nuclear envelope is lined with heterochromatic chromatin, which contains gene-poor regions or transcriptionally silenced genome regions. Transposition of a gene into the nuclear periphery generally results in repression or reduced activity77–79. And lamina-associated sequences present near the Igh and Cyp3a11 genes have been identified, which are sufficient to mediate gene localization to the periphery and silencing80. Nevertheless, it remains to be seen whether lamina-associated sequences are a general feature of lamina- associated domains. Particularly in yeast, the association of genes with nuclear pores appears to carry regulatory information. Several classes of inducible genes translocate, via a DNA-encoded targeting sequence in their 5’ end, from the nuclear interior to the nuclear pore, and their association with pores primes them for rapid induction at a later time point, likely via epigenetic markings81. This observation is in line with the notion that mechanisms of peripheral positioning involve histone modifications. Lamina-associated domains are enriched in H3K9me2 and H3K27me3, and lamina-associated sequences are bound by the transcriptional repressor cKrox in a complex with HDAC3, with loss of HDAC3 resulting in dissociation from the periphery80. Similarly, in Caenorhabditis elegans, peripheral localization and heterochromatin formation is mediated by H3K9 methylation82.

An important observation in these studies is that dissociation of a gene locus from the periphery does not necessarily lead to activation of that locus. Genome-wide analysis of association of genes with lamina in ES cells identified genes that ‘lose’ the interaction with nuclear lamina during the transition from ES cells to neuronal precursors yet are not turned on83. Similarly, many genes that lose their association with the nuclear lamina in the premature-aging disorder Hutchinson-Gilford progeria syndrome, caused by a dominant gain- of-function mutation in lamin A, do not change their activity level84. It appears that although dissociation from the nuclear lamina is not sufficient for activation, loss of interaction with the nuclear periphery may prime these genes for transcriptional upregulation because many of the dissociated yet inactive genes in neuronal precursors were readily upregulated as cells progressed along the lineage pathway into astrocytes83. On the flipside, loss of the H3K9 histone methyltrans- ferase G9a, which has been implicated in gene repression, leads to strong upregulation of some peripheral genes but is not sufficient to displace them from the periphery, suggesting that localization alone is not enough to silence genes85. It will be important to uncover the mechanisms involved in maintaining and relieving the repressed state of this class of lamin-regulated genes.

DNA replication

Eukaryotic DNA is replicated in a highly regulated manner. Replication initiates at specific regions of the genome, called origins of replication. At each S phase, 30,000–50,000 origins of DNA replication are used to duplicate the mammalian genome, and specific regulatory processesensure that origins are selected and used once and only once per cell cycle and at a specific time during S phase86. Although no specific sequences are necessary and sufficient to define animal origins of DNA replication, distinctive chromatin features have been identified that correlate with the specification of replication origins87. Replication origins occur preferentially at CpG islands86,88,89, and there is a clear link between transcription and the timing of replication during S phase, with active genes and gene-rich chromosome regions replicated earlier than inactive and gene-poor regions90–93. The genome was shown to be organized in broad domains, each defined by the timing of replication of the DNA it contains94.

A comparison of replication domains and chromosome contact maps reveals a notable correlation between replication timing and chromosome contacts, suggesting that replication domains correspond to units of chromosome folding in the nucleus95. Moreover, strong conservation was observed between mouse and human, revealing a similar conservation in topologically associated domains18. As replication timing is determined during the G1 phase of the cell cycle92, these data suggest that chromosome folding and duplication are co-regulated during cell proliferation. However, chromosome folding features are robustly maintained even in noncycling cells, indicating that, once determined, the blueprint of chromosome folding is epigenetically stable96. Specific developmental changes of both replication timing and chromosome contacts have been reported18,94,97. These changes correlate with, but do not fully account for, changes in transcription. In particular, in mouse ES cells triggered to differentiate, individual neighboring replication domains can consolidate into larger domains. These replication-timing switches correlate with expression changes of some but not all genes, with weaker promoters more correlated than strong ones. These results suggest that cells maintain the memory of global chromosome architecture while they can reprogram selected genome domains in response to regulatory cues94. As DNA replication timing is one of the genome features that correlates best with chromatin contact maps, a crucial issue will be to address whether replication domains arise as a consequence of spatial chromosome reorganization or whether changes in replication timing drive changes in chromatin architecture98.

DNA repair and translocations

The various levels of genome topology affect DNA repair and genome maintenance in several ways. At the molecular level, local chromatin organization may influence the efficiency of DNA repair. It has been long documented that the rate of repair differs widely between individual double-strand breaks (DSBs)99,100. Slowly repaired lesions are frequently associated with heterochromatin regions, and phosphorylation of H2AX, a hallmark of DSBs, appears to occur more readily in euchromatin compared to heterochromatin100. Furthermore, heterochromatin in S. cerevisiae and in mammalian cells is more refractory to phosphorylation of H2AX, suggesting that higher-order chromatin structure may impede efficient access of the repair machinery to the DNA lesion. Mechanisms to counteract the inhibitory effect of condensed chromatin in repair have emerged. Chromatin appears to decondense on a large scale around the site of DNA damage101, and the structural heterochromatin protein HP1 as well as its interaction partner KAP1 are released from the site of damage102,103. Moreover, in flies, damaged regions of heterochromatin are rapidly expelled from the chromosome body for repair104. This may serve two important purposes: first, to ensure ready access of the repair machinery to the damage site; and second, to minimize the risk of illegitimate joining during homologous recombination repair among the abundant repeat sequences found in heterochromatin.

Spatial genome organization has an even more important role in the formation of cancer-associated gene translocations. One of the key steps in the formation of translocations is the pairing of persistently broken chromosomes to ultimately undergo illegitimate joining. Given that most mammalian DSBs only undergo constrained local motion within ~2 μm (ref. 105), the probability of two persistent DSBs to undergo a translocation is directly related to their position in the nuclear space. FISH analysis has demonstrated a strong correlation between translocation frequency of two loci and their physical separation in 3D space. For example, in Burkitt’s lymphoma, the frequently translocating MYC and IGH@ loci are on average in closer spatial proximity than the less frequently translocated MYC and IGK@ loci106. Similar correlations have been observed for many other translocation pairs and were more recently confirmed by 3C approaches66,107–109. These observations strongly suggest that the nonrandom arrangement of chromosomes and gene loci in 3D space substantially influences which genes translocate with each other.

The situation is somewhat different in yeast. DSBs in yeast migrate to the repair centers or to the nuclear pore complex where they undergo repair events110,111. In addition, a system of inner nuclear membrane proteins appears to stabilize and protect repetitive rRNA sequences, which are located at the nuclear periphery in yeast112, unlike in mammalian cells. But even in the much more dynamic environment of the yeast nucleus, recombination events occur more frequently between spatially proximal gene locations. An example is the mating switch gene MATAa (MATa), which preferentially recombines with the proximal HML locus rather than the more distal HMR locus113.

The effect of the spatial arrangement of the genome on translocation frequency has an important implication. Considering that the spatial arrangement of genomes differs between tissues and cell types, it seems likely that the well-documented tissue specificity of translocations is at least partially driven by the tissue-specific spatial arrangement of genomes2. Correlative data support this notion. For example, chromosomes 5 and 12 are frequently found in spatial proximity in liver cells and are frequently translocated in hepatomas, but they are spatially separated in other cell types such as lymphocytes and are only rarely found in lymphoma translocations114. Similar observations have been made for anaplastic large cell lymphoma and prostate tumors115,116, suggesting that spatial proximity is a major determinant of clinically relevant formation of translocations.

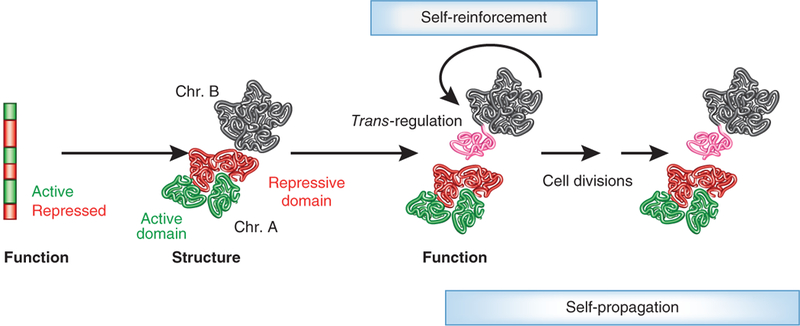

A function-structure-function model of the genome

It has been much debated whether genome organization determines function or whether genome topology is merely a reflection of function. Considering the available data, both sides of the argument appear to be valid. On the one hand, there is little doubt that the formation of local chromatin loops, say between an enhancer and a promoter, is a mandatory step in function, and gene localization close to nuclear landmarks such as the nuclear periphery undoubtedly affects their activity. On the other hand, such associations or precise position of a gene in 3D space is not an absolute requirement for proper function. The combined insight from single-cell imaging data and population- based, but genome-wide, analysis is beginning to resolve the argument by pointing to a self-enforcing, self-perpetuating function-structure- function model of genome organization2,3 (Fig. 3).

Figure 3.

A model depicting the interplay of genome structure and function. The transcriptional activity of genome regions determines the formation of chromatin domains (red and green). Domains are defined patterns of nucleosome positioning, histone modifications and differential higher-order folding. The activity state of a ‘neutral’ genome region (black) is determined by its physical association with either an active or repressive environment, and these long-range contacts may thus change functional states (indicated by transformation of the portion of the black chromosome closest to a repressive (red) domain of another chromosome to pink). The functional status of the chromatin domain feeds back and reinforces its structural features (self-enforcement). Chromatin structure-function relationships are heritable (self-propagation).However, given the inherent plasticity of the system, even in terminally differentiated states strong physiological or environmental stimuli may switch chromatin domains, allowing for the possibility of cell reprogramming.

This view is based on one of the key features of genome topology, which has informed, but also complicated, our thinking about genome function, and that is the fact that effects of genome topology modulate, but often do not determine, genome function. For example, at the level of the chromatin fiber, a consensus DNA motif for a given transcription factor is generally not sufficient for its activity.

However, when placed in the specific context defined by genome domains (that is, open chromatin, which allows access of regula-tory factors that cannot access the same binding site in condensed chromatin), the motif becomes functional. Similar principles apply at higher levels of organization. A gene poised for activity may be silent unless—either by yet unknown, dedicated mechanisms or by chance—it is placed near a nuclear region of active transcription (Fig. 3). Such a modulatory function of genome topology is consistent with the observed stochastic nature of gene expression.

Considering genome topology as a modulatory rather than a deterministic regulator of genome function leads to a self-organization model in which genome activity drives the formation of genome topology, and the resulting organization features, in turn, affect genome function (Fig. 3). At the level of the chromatin fiber, physical domains are formed by the boundaries that separate active from inactive regions; these domains fold into higher-order domains in chromosome territories and provide functionally distinct chromatin environments. At the next level of organization, multiple domains on separate chromosomes associate to form 3D spatial arrangements. Their assembly is driven by the macromolecular machines that regulate genome function, leading to the formation of nuclear structures such as nuclear bodies or chromatin domains and territories. In turn, these structures generate nuclear microenvironments, and the bioavailability of regulatory factors in these domains in turn affects the activity of the associated genome regions. The topological features of the genome are heritable and are passed on during the life of cells and to their progeny as long as the functional status of the cell does not change—for example, during differentiation, development or in disease. However, given the inherent plasticity of protein-DNA and DNA-DNA interactions, even in terminally differentiated states strong physiological or environmental stimuli may switch chromatin domains, allowing for the possibility of cell reprogramming. This model predicts that higher-order genome organization is primarily driven by genome activity.

A key feature of a function-structure-function model is its selfreinforcing and self-propagating nature. Gene expression programs are obviously to a large extent hard-wired in the primary DNA sequence, but additional mechanisms such as epigenetic regulation and genome topology superimpose additional layers of regulation. The function of these secondary mechanisms is twofold. On the one hand, they maintain and perpetuate the ground state generated by the genetic information by acting as a buffer to potentially detrimental environmental influences, such as cellular stress or aberrant signaling. This is achieved by generating structural genome features such as euchromatin or heterochromatin domains that protect the status quo by accumulating co--regulated genome regions in a com-- mon environment, such as chromatin domains. The structure rein-forces the activity status of the genes in the domain. On the other hand, epigenetic mechanisms may change the ground state of the system by placing genes in a new environment that alters their function, such as by placing an active gene into a heterochromatic, repressed region. In this case, the structural features of the chromatin domain impose their function on the genome region. The system becomes self--reinforcing in that the newly added genome region adds to, and strengthens, the features of the chromatin domain. If the chromatin state is heritable, for example, when specified by DNA or histone modifications, the system also becomes self--propagating over multiple generations (Fig. 3).

Conclusions

Great strides have been made in the last decade in uncovering the principles by which genomes are organized in the cell. Our thinking about the functional role of genome topology has been greatly shaped by the concept of epigenetics, which has emerged in parallel and has popularized the notion that genomes and their sequence are not absolutely deterministic. We are at a point where we know enough about some of the key features of genome organization and we have the technology, particularly imaging and genome-wide mapping methods, to make the next step. The focus must now be on under-standing the physiological and pathological relevance of genome topology, and there are clear indications of its importance in disease. Many histone modifiers and chromatin remodelers that affect chro-matin fiber structure have been identified as disease agents, including in numerous cancers; global genome architecture is dramatically altered in many diseases; and one of the most intriguing families of human diseases are the laminopathies caused by mutations in lamin proteins. The path forward is two-pronged. On the one hand, genome-topology features at all levels must be comprehensively mapped in disease and physiologically relevant samples, and compared to gene expression and epigenetic profiles as well as morphological and cellular features, in an attempt to link genome topology to functional readouts. On the other hand, experiments to perform targeted manipulations of chromatin structure and genome topology are required to fully uncover the mechanistic basis for all levels of genome topology. Both approaches are now feasible and should lead to uncovering the functional implications of genome topology. Given the wealth of molecular information we have amassed on genome function, combined with the detailed cell biological characterization of genomes over the last 10 years, it is likely that after being neglected for decades, the genome will rapidly become one of the best understood cellular structures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

G.C. was supported by the European Research Council (ERC-2008-AdG No 232947), the Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, the European Network of Excellence EpiGeneSys and the Agence Nationale de la Recherche. T.M. was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the US National Institutes of Health, the National Cancer Institute, the Center for Cancer Research.

Footnotes

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Lanctot C, Cheutin T, Cremer M, Cavalli G & Cremer T Dynamic genome architecture in the nuclear space: regulation of gene expression in three dimensions. Nat. Rev. Genet. 8, 104–115 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Misteli T Beyond the sequence: Cellular organization of genome function. Cell 128, 787–800 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rajapakse I & Groudine M On emerging nuclear order. J. Cell Biol. 192, 711–721 (2011).This comprehensive overview of basic principles of genome organization includes a discussion of the concept of self-organized genome architecture.

- 4.Hakim O & Misteli T SnapShot: chromosome confirmation capture. Cell 148, 1068 e1–e2 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.van Steensel B & Dekker J Genomics tools for unraveling chromosome architecture. Nat. Biotechnol. 28, 1089–1095 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Branco MR & Pombo A Intermingling of chromosome territories in interphase suggests role in translocations and transcription-dependent associations. PLoS Biol. 4, e138 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zimmer C & Fabre E Principles of chromosomal organization: lessons from yeast. J. Cell Biol. 192, 723–733 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sanyal A, Lajoie BR, Jain G & Dekker J The long-range interaction landscape of gene promoters. Nature 489, 109–113 (2012).This work comprehensively maps interactions between transcription start sites and distal elements in 1% of the human genome to generate first insights into the spatial arrangements of genes and regulatory elements in their 3D context.

- 9.Chubb JR, Boyle S, Perry P & Bickmore WA Chromatin motion is constrained by association with nuclear compartments in human cells. Curr. Biol. 12, 439–445 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ernst J et al. Mapping and analysis of chromatin state dynamics in nine human cell types. Nature 473, 43–49 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Filion GJ et al. Systematic protein location mapping reveals five principal chromatin types in Drosophila cells. Cell 143, 212–224 (2010). This work characterizes five types of chromatin based on combinatorial enrichment of histone modifications and chromatin-binding proteins.

- 12.Kharchenko PV et al. Comprehensive analysis of the chromatin landscape in Drosophila melanogaster. Nature 471, 480–485 (2011). Refs. 12 and 15 are two of several reports published from the ModENCODE and the ENCODE projects, respectively. Similar to ref. 11, they highlight the existence of chromosomal domains characterized by distinct epigenomic landscapes in D. melanogaster and humans. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu I et al. Broad chromosomal domains of histone modification patterns in C. elegans. Genome Res. 21, 227–236 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwartz YB et al. Alternative epigenetic chromatin states of polycomb target genes. PLoS Genet. 6, e1000805 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dunham I et al. An integrated encyclopedia of DNA elements in the human genome. Nature 489, 57–74 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Caron H et al. The human transcriptome map: clustering of highly expressed genes in chromosomal domains. Science 291, 1289–1292 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gierman HJ et al. Domain-wide regulation of gene expression in the human genome. Genome Res. 17, 1286–1295 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dixon JR et al. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature 485, 376–380 (2012). Results reported in references 18–21 demonstrate the existence of topological domains in the D. melanogaster, mouse and human genomes. This work characterized the chromatin features at boundaries subdividing these domains as well as the nature of the long-distance contacts between different domains. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hou C, Li L, Qin ZS & Corces VG Gene density, transcription, and insulators contribute to the partition of the Drosophila genome into physical domains. Mol. Cell 48, 471–484 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sexton T et al. Three-dimensional folding and functional organization principles of the Drosophila genome. Cell 148, 458–472 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nora EP et al. Spatial partitioning of the regulatory landscape of the X-inactivation centre. Nature 485, 381–385 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shopland LS et al. Folding and organization of a contiguous chromosome region according to the gene distribution pattern in primary genomic sequence. J. Cell Biol. 174, 27–38 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boutanaev AM, Mikhaylova LM & Nurminsky DI The pattern of chromosome folding in interphase is outlined by the linear gene density profile. Mol. Cell. Biol. 25, 8379–8386 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simonis M et al. High-resolution identification of balanced and complex chromosomal rearrangements by 4C technology. Nat. Methods 6, 837–842 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Noordermeer D et al. The dynamic architecture of Hox gene clusters. Science 334, 222–225 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wong H et al. A predictive computational model of the dynamic 3D interphase yeast nucleus. Curr. Biol. 22, 1881–1890 (2012). Work reported in refs. 26 and 27 suggests that yeast higher-order nuclear architecture is largely driven by chromosome polymer structure. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tjong H, Gong K, Chen L & Alber F Physical tethering and volume exclusion determine higher-order genome organization in budding yeast. Genome Res. 22, 1295–1305 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guelen L et al. Domain organization of human chromosomes revealed by mapping of nuclear lamina interactions. Nature 453, 948–951 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kind J & van Steensel B Genome-nuclear lamina interactions and gene regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 320–325 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wang J et al. Promyelocytic leukemia nuclear bodies associate with transcriptionally active genomic regions. J. Cell Biol. 164, 515–526 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shopland LS et al. Replication-dependent histone gene expression is related to Cajal body (CB) association but does not require sustained CB contact. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 565–576 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bantignies F et al. Polycomb-dependent regulatory contacts between distant Hox loci in Drosophila. Cell 144, 214–226 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheutin T & Cavalli G Progressive polycomb assembly on H3K27me3 compartments generates polycomb bodies with developmentally regulated motion. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002465 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eskiw CH et al. Transcription factories and nuclear organization of the genome. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 75, 501–506 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Meaburn KJ, Gudla PR, Khan S, Lockett SJ & Misteli T Disease-specific gene repositioning in breast cancer. J. Cell Biol. 187, 801–812 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kalhor R, Tjong H, Jayahilaka N, Alber F & Chen L Solid-phase chromosome conformation capture for structural characterization of genome architectures. Nat. Biotechnol. 30, 90–98 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cvackova Z, Masata M, Stanek D, Fidlerova H & Raska I Chromatin position in human HepG2 cells: although being non-random, significantly changed in daughter cells. J. Struct. Biol. 165, 107–117 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hou C & Corces VG Throwing transcription for a loop: expression of the genome in the 3D nucleus. Chromosoma 121, 107–116 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.O’Sullivan JM et al. Gene loops juxtapose promoters and terminators in yeast. Nat. Genet. 36, 1014–1018 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tan-Wong SM, French JD, Proudfoot NJ & Brown MA Dynamic interactions between the promoter and terminator regions of the mammalian BRCA1 gene. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 5160–5165 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tan-Wong SM, Wijayatilake HD & Proudfoot NJ Gene loops function to maintain transcriptional memory through interaction with the nuclear pore complex. Genes Dev. 23, 2610–2624 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tan-Wong SM et al. Gene loops enhance transcriptional directionality. Science 338, 671–675 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tolhuis B, Palstra RJ, Splinter I., Grosveld F & de Laat W Looping and interaction between hypersensitive sites in the active beta-globin locus. Mol. Cell 10, 1453–1465 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Orom UA & Shiekhattar R Noncoding RNAs and enhancers: complications of a long-distance relationship. Trends Genet. 27, 433–439 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang KC et al. A long noncoding RNA maintains active chromatin to coordinate homeotic gene expression. Nature 472, 120–124 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Deng W et al. Controlling long-range genomic interactions at a native locus by targeted tethering of a looping factor. Cell 149, 1233–1244 (2012). This work demonstrates that chromatin looping causally underlies gene regulation, as determined by experimentally manipulating the formation of chromatin loops. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vernimmen D et al. Polycomb eviction as a new distant enhancer function. Genes Dev. 25, 1583–1588 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li G et al. Extensive promoter-centered chromatin interactions provide a topological basis for transcription regulation. Cell 148, 84–98 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tiwari VK, Cope L, McGarvey KM, Ohm JE & Baylin SB A novel 6C assay uncovers Polycomb-mediated higher order chromatin conformations. Genome Res. 18, 1171–1179 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tiwari VK et al. PcG proteins, DNA methylation, and gene repression by chromatin looping. PLoS Biol. 6, 2911–2927 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lanzuolo C, Roure V, Dekker J, Bantignies F & Orlando V Polycomb response elements mediate the formation of chromosome higher-order structures in the bithorax complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 1167–1174 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Breiling A, Turner BM, Bianchi ME & Orlando V General transcription factors bind promoters repressed by Polycomb group proteins. Nature 412, 651–655 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lanzuolo C & Orlando V The function of the epigenome in cell reprogramming. Ceil. Moi. Life Sci. 64, 1043–1062 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Saurin AJ, Shao Z, i rdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P & Kingston RE A Drosophila Polycomb group complex includes Zeste and dTAFII proteins. Nature 412, 655–660 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cleard F, Moshkin Y, Karch F & Maeda RK Probing long-distance regulatory interactions in the Drosophila meianogaster bithorax complex using Dam identification. Nat. Genet. 38, 931–935 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Li B, Carey M & Workman JL The role of chromatin during transcription. Cell 128, 707–719 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wicks K & Knight JC Transcriptional repression and DNA looping associated with a novel regulatory element in the final exon of the lymphotoxin-beta gene. Genes Immun. 12, 126–135 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hsu PY et al. Estrogen-mediated epigenetic repression of large chromosomal regions through DNA looping. Genome Res. 20, 733–744 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hewetson A & Chilton BS Progesterone-dependent deoxyribonucleic acid looping between RUSH/SMARCA3 and Egr-1 mediates repression by c-Rel. Moi. Endocrinoi. 22, 813–822 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yang J & Corces VG Insulators, long-range interactions, and genome function. Cur. Opin. Genet. Dev. 22, 86–92 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Thurman RE et al. The accessible chromatin landscape of the human genome. Nature 489, 75–82 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Van Bortle K et al. Drosophiia CTCF tandemly aligns with other insulator proteins at the borders of H3K27me3 domains. Genome Res. 22, 2176–2187 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Schwartz YB et al. Nature and function of insulator protein binding sites in the Drosophiia genome. Genome Res. 22, 2188–2198 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Masui O et al. Live-cell chromosome dynamics and outcome of X chromosome pairing events during ES cell differentiation. Cell 145, 447–458 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Augui S et al. Sensing X chromosome pairs before X inactivation via a novel X-pairing region of the Xic. Science 318, 1632–1636 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zhang Y et al. Spatial organization of the mouse genome and its role in recurrent chromosomal translocations. Cell 148, 908–921 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zhao Z et al. Circular chromosome conformation capture (4C) uncovers extensive networks of epigenetically regulated intra- and interchromosomal interactions. Nat. Genet. 38, 1341–1347 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sandhu KS et al. Nonallelic transvection of multiple imprinted loci is organized by the H19 imprinting control region during germline development. Genes Dev. 23, 2598–2603 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Ling JQ et al. CTCF mediates interchromosomal colocalization between Igf2/H19 and Wsb1/Nf1. Science 312, 269–272 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Schoenfelder S et ai. Preferential associations between co-regulated genes reveal a transcriptional interactome in erythroid cells. Nat. Genet. 42, 53–61 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Dundr M & Misteli T Biogenesis of nuclear bodies. Coid Spring Harb. Perspect. Bioi. 2, a000711 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Noordermeer D et al. Variegated gene expression caused by cell-specific long- range DNA interactions. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 944–951 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Spilianakis CG, Lalioti MD, Town T, Lee GR & Flavell RA Interchromosomal associations between alternatively expressed loci. Nature 435, 637–645 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Lomvardas S et ai. Interchromosomal interactions and olfactory receptor choice. Cell 126, 403–413 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Clowney EJ et ai. Nuclear aggregation of olfactory receptor genes governs their monogenic expression. Cell 151, 724–737 (2012). This work reveals that, in mouse olfactory neurons, silent olfactory receptor genes from different chromosomes converge in a small number of heterochromatic foci, suggesting that monogenic and monoallelic expression of olfactory receptors may be dependent on nuclear organization. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Apostolou E & Thanos D Virus infection induces NF-KB-dependent interchromosomal associations mediating monoallelic IFN-p gene expression. Cell 134, 85–96 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Kumaran RI & Spector DL A genetic locus targeted to the nuclear periphery in living cells maintains its transcriptional competence. J. Cell Biol. 180, 51–65 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Finlan LE et al. Recruitment to the nuclear periphery can alter expression of genes in human cells. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000039 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Reddy KL, Zullo JM, Bertolino E & Singh H Transcriptional repression mediated by repositioning of genes to the nuclear lamina. Nature 452, 243–247 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Zullo JM et al. DNA sequence-dependent compartmentalization and silencing of chromatin at the nuclear lamina. Cell 149, 1474–1487 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Egecioglu D & Brickner JH Gene positioning and expression. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 23, 338–345 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Towbin BD et al. Step-wise methylation of Histone H3K9 positions heterochromatin at the nuclear periphery. Cell 150, 934–947 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Peric-Hupkes D et al. Molecular maps of the reorganization of genome-nuclear lamina interactions during differentiation. Moi. Cell 38, 603–613 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Kubben N et al. Mapping of lamin A- and progerin-interacting genome regions. Chromosoma 121, 447–464 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Yokochi T et al. G9a selectively represses a class of late-replicating genes at the nuclear periphery. Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 19363–19368 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Mechali M Eukaryotic DNA replication origins: many choices for appropriate answers. Nat. Rev. Moi. Cell Biol. 11, 728–738 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schwaiger M et al. Chromatin state marks cell-type- and gender-specific replication of the Drosophiia genome. Genes Dev. 23, 589–601 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Cadoret JC et al. Genome-wide studies highlight indirect links between human replication origins and gene regulation. Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA 105, 15837–15842 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Cayrou C, Gregoire D, Coulombe P, Danis E & Mechali M Genome-scale identification of active DNA replication origins. Methods 57, 158–164 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Danis E et al. Specification of a DNA replication origin by a transcription complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 721–730 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Schubeler D et al. Genome-wide DNA replication profile for Drosophiia meianogaster: a link between transcription and replication timing. Nat. Genet. 32, 438–442 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Hiratani I, Takebayashi S, Lu J & Gilbert DM Replication timing and transcriptional control: beyond cause and effect-part II. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 19, 142–149 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gilbert DM Replication timing and transcriptional control: beyond cause and effect. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 14, 377–383 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hiratani I et al. Global reorganization of replication domains during embryonic stem cell differentiation. PLoS Bioi. 6, e245 (2008). Work described in refs. 94 and 95 reveals a tight correlation between the timing of replication in large chromosomal domains and their spatial organization as assessed by 3C technologies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Ryba T et al. Evolutionarily conserved replication timing profiles predict long- range chromatin interactions and distinguish closely related cell types. Genome Res. 20, 761–770 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Moindrot B et al. 3D chromatin conformation correlates with replication timing and is conserved in resting cells. Nucieic Acids Res. 40, 9470–9481 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Takebayashi S, Dileep V, Ryba T, Dennis JH & Gilbert DM Chromatin interaction compartment switch at developmentally regulated chromosomal domains reveals an unusual principle of chromatin folding. Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 12574–12579 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Gilbert DM Cell fate transitions and the replication timing decision point. J. Cell Biol. 191, 899–903 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Goodarzi AA et al. ATM signaling facilitates repair of DNA double-strand breaks associated with heterochromatin. Moi. Cell 31, 167–177 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Cowell IG et al. gammaH2AX foci form preferentially in euchromatin after ionising-radiation. PLoS ONE 2, e1057 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Kruhlak MJ et al. Changes in chromatin structure and mobility in living cells at sites of DNA double-strand breaks. J. Cell Biol. 172, 823–834 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Ayoub N, Jeyasekharan AD, Bernal JA & Venkitaraman AR HP1-beta mobilization promotes chromatin changes that initiate the DNA damage response. Nature 453, 682–686 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Ziv Y et al. Chromatin relaxation in response to DNA double-strand breaks is modulated by a novel ATM- and KAP-1 dependent pathway. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 870–876 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Chiolo I et al. Double-strand breaks in heterochromatin move outside of a dynamic HP1a domain to complete recombinational repair. Cell 144, 732–744 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Soutoglou E et al. Positional stability of single double-strand breaks in mammalian cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 9, 675–682 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Roix JJ, McQueen PG, Munson PJ., Parada LA & Misteli T Spatial proximity of translocation-prone gene loci in human lymphomas. Nat. Genet. 34, 287–291 (2003). This work provides extensive evidence for a key role of spatial genome organization in determining chromosome translocations. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Hakim O et al. DNA damage defines sites of recurrent chromosomal translocations in B lymphocytes. Nature 484, 69–74 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Klein IA et al. Translocation-capture sequencing reveals the extent and nature of chromosomal rearrangements in B lymphocytes. Cell 147, 95–106 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Chiarle R et al. Genome-wide translocation sequencing reveals mechanisms of chromosome breaks and rearrangements in B cells. Cell 147, 107–119 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Dion V, Kalck V, Horigome C, Towbin BD & Gasser SM Increased mobility of double-strand breaks requires Mec1, Rad9 and the homologous recombination machinery. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 502–509 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Mine-Hattab J & Rothstein R Increased chromosome mobility facilitates homology search during recombination. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 510–517 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Mekhail K, Seebacher J, Gygi SP & Moazed D Role for perinuclear chromosome tethering in maintenance of genome stability. Nature 456, 667–670 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Bressan DA, Vazquez J & Haber JE Mating type-dependent constraints on the mobility of the left arm of yeast chromosome III. J. Cell Biol. 164, 361–371 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Parada L, McQueen P & Misteli T Tissue-specific spatial organization of genomes. Genome Bioi. 5, R44 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Mathas S et al. Gene deregulation and spatial genome reorganization near breakpoints prior to formation of translocations in anaplastic large cell lymphoma. Proc. Nati. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 5831–5836 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lin C et al. Nuclear receptor-induced chromosomal proximity and DNA breaks underlie specific translocations in cancer. Cell 139, 1069–1083 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Meshorer E et al. Hyperdynamic plasticity of chromatin proteins in pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Dev. Cell 10, 105–116 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Mikkelsen TS et al. Genome-wide maps of chromatin state in pluripotent and lineage-committed cells. Nature 448, 553–560 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Efroni S et al. Global transcription in pluripotent embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell 2, 437–447 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Fussner E et al. Constitutive heterochromatin reorganization during somatic cell reprogramming. EMBO J. 30, 1778–1789 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Gaspar-Maia A et al. Chd1 regulates open chromatin and pluripotency of embryonic stem cells. Nature 460, 863–868 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Ho L et al. esBAF facilitates pluripotency by conditioning the genome for LIF/ STAT3 signalling and by regulating polycomb function. Nat. Cell Biol. 13, 903–913 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Biran A & Meshorer E Concise review: chromatin and genome organization in reprogramming. Stem Cells 30, 1793–1799 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Puschendorf M et al. PRC1 and Suv39h specify parental asymmetry at constitutive heterochromatin in early mouse embryos. Nat. Genet. 40, 411–420 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Meister P, Towbin BD, Pike BL, Ponti A & Gasser SM The spatial dynamics of tissue-specific promoters during C. elegans development. Genes Dev. 24, 766–782 (2010). This study reveals a developmental stage-specific and cell differentiation-specific regulation of gene positioning in the 3D space of the nucleus in C. elegans, opening the way to genetic dissection of developmental determinants of nuclear organization and function. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Ishimi Y et al. Changes in chromatin structure during aging of human skin fibroblasts. Exp. Cell Res. 169, 458–467 (1987). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.O’Sullivan RJ, Kubicek S, Schreiber SL & Karlseder J Reduced histone biosynthesis and chromatin changes arising from a damage signal at telomeres. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 1218–1225 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Scaffidi P & Misteli T Lamin A-dependent nuclear defects in human aging. Science 312, 1059–1063 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.O’Sullivan RJ & Karlseder J The great unravelling: chromatin as a modulator of the aging process. Trends Biochem. Sci. 37, 466–476 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Pegoraro G et al. Aging-related chromatin defects via loss of the NURD complex. Nat. Cell Biol. 11, 1261–1267 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Feser J et al. Elevated histone expression promotes life span extension. Mol. Cell 39, 724–735 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Sutton A, Bucaria J, Osley MA & Sternglanz R Yeast ASF1 protein is required for cell cycle regulation of histone gene transcription. Genetics 158, 587–596 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Lesur I & Campbell JL The transcriptome of prematurely aging yeast cells is similar to that of telomerase-deficient cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 1297–1312 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Burgess RC, Misteli T & Oberdoerffer P DNA damage, chromatin, and transcription: the trinity of aging. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 24, 724–730 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Oberdoerffer P et al. SIRT1 redistribution on chromatin promotes genomic stability but alters gene expression during aging. Cell 135, 907–918 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]