Abstract

The plant-specific WRKY transcriptional regulatory factors have been proven to play vital roles in plant growth, development, and responses to biotic and abiotic stresses. However, there are few studies on the WRKY gene family in sugarcane (Saccharum spp.). In the present study, the characterization of a new subgroup, IIc WRKY protein ScWRKY3, from a Saccharum hybrid cultivar is reported. The ScWRKY3 protein was localized in the nucleus of Nicotiana benthamiana leaves and showed no transcriptional activation activity and no toxic effects on the yeast strain Y2HGold. An interaction between ScWRKY3 and a reported sugarcane protein ScWRKY4, was confirmed in the nucleus. The ScWRKY3 gene had the highest expression level in sugarcane stem pith. The transcript of ScWRKY3 was stable in the smut-resistant Saccharum hybrid cultivar Yacheng05-179, while it was down-regulated in the smut-susceptible Saccharum hybrid cultivar ROC22 during inoculation with the smut pathogen (Sporisorium scitamineum) at 0–72 h. ScWRKY3 was remarkably up-regulated by sodium chloride (NaCl), polyethylene glycol (PEG), and plant hormone abscisic acid (ABA), but it was down-regulated by salicylic acid (SA) and methyl jasmonate (MeJA). Moreover, transient overexpression of the ScWRKY3 gene in N. benthamiana indicated a negative regulation during challenges with the fungal pathogen Fusarium solani var. coeruleum or the bacterial pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum in N. benthamiana. The findings of the present study should accelerate future research on the identification and functional characterization of the WRKY family in sugarcane.

Keywords: sugarcane, WRKY, subcellular localization, gene expression pattern, protein-protein interaction, transient overexpression

1. Introduction

Plant growth and development are vulnerable to several external environmental challenges, such as drought, high salinity, cold, and pathogens. There are complex metabolic regulation mechanisms in plants which enhance their resistance to a wide range of stresses through physiological changes largely controlled at the molecular level [1]. The transcription factors (TFs) in plant cells interact with specific DNA sequences in target gene promoters to activate or inhibit transcription and expression of target genes, thereby regulating the expression of these genes. This modulation causes adaptation to the effects and damage from various stresses [2].

As one of the largest plant-specific families of TFs, WRKY has been proven to be widely implicated in responses to biotic and abiotic stresses [3,4]. WRKY TFs are also a vital part of the signaling pathway network of plants, regulating physiological and biochemical processes [5]. The WRKY proteins were named based on a DNA-binding WRKY domain, which contains approximately 60 amino acid residues. This domain features a WRKYGQK sequence at its N-terminal end together with a CX45CX22-23HXH (C2H2-type) or CX7CX23HXC (C2HC-type) zinc finger-like motif at the C-terminal [1,5,6]. Although the DNA-binding domain is highly conserved, the overall structure of the WRKY proteins is highly diverse and can be divided into three groups (I, II, and III) including five subgroups (IIa-IIe) in group II. These groupings are categorized according to the number of WRKY domains and are also based on features of the zinc finger-like motif [6,7]. Previous studies have indicated that WRKYs with similar roles usually have related functions. For example, WRKYs in groups I and III are involved in epidermal development, senescence, and abiotic stress, while WRKYs in group II are related to low phosphorus stress, disease resistance, secondary root formation, and abiotic stress, with a few exceptions observed [8].

Currently, WRKY genes have been identified in various plant species. There is a total of 72 WRKYs in the model dicot Arabidopsis thaliana [5]. In monocots, there are 103 WRKYs in Oryza sativa [9], 116 WRKYs in Zea mays [10], 105 WRKYs in Setaria italica [11], 68 WRKYs in Sorghum bicolor [12], and 45 WRKYs in Hordeum vulgare [13]. It has been reported that 30 WRKY genes in A. thaliana were responsive to salt stress [14]. Also, 58 WRKY genes in Z. mays and 19 WRKY genes in Phaseolus vulgaris were related to drought stress [15,16]. Qiu et al. [17] indicated that ten of 13 candidate WRKY genes in rice can respond to sodium chloride (NaCl), polyethylene glycol (PEG), low temperature, or high temperature stress. Wu et al. [18] showed that eight of the 15 candidate WRKY genes in wheat responded to low temperature, NaCl, or PEG stress. Previous studies showed that 49 A. thaliana WRKY genes were induced by Pseudomonas syringae or salicylic acid (SA) [19]. Fifteen WRKYs were induced by Magnaporthe grisea, and 12 of them were simultaneously induced by Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae [9]. Several other reports also demonstrated that WRKYs can positively or negatively regulate the responses of plants to external biotic or abiotic stresses [20,21,22]. Moreover, numerous studies have reported that WRKYs are widely involved in a complicated signal transduction network, which may work together with upstream or downstream components, or may interact with other WRKY proteins during physiological processes or in response to various biotic and abiotic stimuli [1,23,24]. These reports provide the foundation for studying the tolerance mechanism of plant WRKY genes to environmental stress.

Sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) is not only the foremost sugar-producing crop, but also the one that has potential as a bioenergy resource [25]. The study on signal transduction in sugarcane growth, development, and its responses to the external environment, especially the functional analysis of TFs, is of great significance for sugarcane molecular breeding. As reported, there were 26 WRKY-like proteins discovered in a publicly available sugarcane expressed sequence tag (EST) database via an in silico study, and their phylogenetic relationships were determined [26]. Beyond that, only two other sugarcane group IIc WRKY proteins, Sc-WRKY (GenBank Accession No. GQ246458.1) [27] and ScWRKY4 (GenBank Accession No. MG852087.1) [28], have been isolated from Saccharum hybrid cultivar FN22 and Saccharum hybrid cultivar ROC22 respectively and characterized by molecular techniques. Sc-WRKY and ScWRKY4 were both shown to be related to tolerance enhancement to PEG and NaCl stresses [27,28]. Under biotic treatment, Sc-WRKY may play a positive role in response to smut pathogen [27], while ScWRKY4 may be negatively or probably not involved in this regulation [28], suggesting the functional differentiation of group IIc ScWRKYs in smut pathogen resistance. In this study, a new group IIc WRKY gene family member, ScWRKY3 (GenBank Accession No. MK034706), was screened from our previous sugarcane transcriptome data [29]. The sequence characteristics of ScWRKY3 and its subcellular localization, transcriptional activation activity, and its protein-protein interaction with ScWRKY4 were analyzed. The expression profiles of ScWRKY3 in sugarcane tissues in response to various stresses were assessed, as well as the effects that occurred in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves after challenging with the bacterial pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum and the fungal pathogen Fusarium solani var. coeruleum.

2. Results

2.1. Bioinformatics Analysis of ScWRKY3 Gene

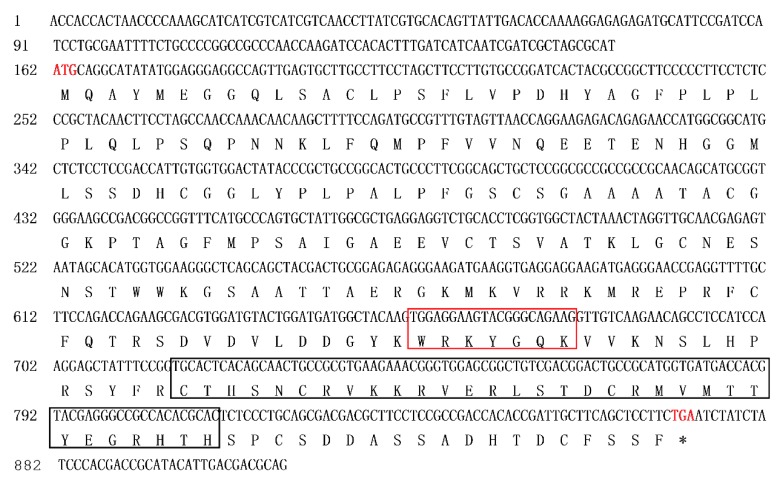

There was no nucleic acid sequence difference or amino acid sequence difference in ScWRKY3 between smut-susceptible Saccharum hybrid cultivar ROC22 and smut-resistant Saccharum hybrid cultivar Yacheng05-179 (Figure S1). As shown in Figure 1, the ScWRKY3 gene has a cDNA length of 910 bp containing an open reading frame (ORF) from position 162 to 872, and its encoded amino acid residues contain a conserved WRKY domain from position 166 to 223. Bioinformatics analysis revealed that the ScWRKY3 protein has a molecular weight of 25.98 kDa (Table S1). The theoretical isoelectric point (pI), grand average of hydrophobicity (GRAVY), and instability index (II) of ScWRKY3 were 8.58, -0.49, and 56.08 (Table S1), respectively, suggesting that ScWRKY3 might be an unstable basic hydrophilic protein. Secondary structure prediction showed that ScWRKY3 is mainly composed of random coil (69.07%), alpha-helix (18.22%), and extended strand (12.70%) portions (Figure S2). In addition, the ScWRKY3 protein was predicted to have no signal peptide or transmembrane domain (Figure S3). Euk-mPLoc 2.0 software [30] showed that ScWRKY3 has the highest probability of localization in the nucleus (Figure S4).

Figure 1.

Nucleotide acid sequences and deduced amino acid sequences of the sugarcane ScWRKY3 gene obtained by PCR amplification. The sequence of the WRKY motif (WRKYGQK) is highlighted in the red box, and that of the C2H2 domain (CX4CX23HXH) in the black box. The upstream sequences to start codon ATG (marked in red font) is 5′ untranslated region (UTR) and the downstream sequences to stop codon TGA (marked in red font) is 3′UTR of ScWRKY3. *: stop codon.

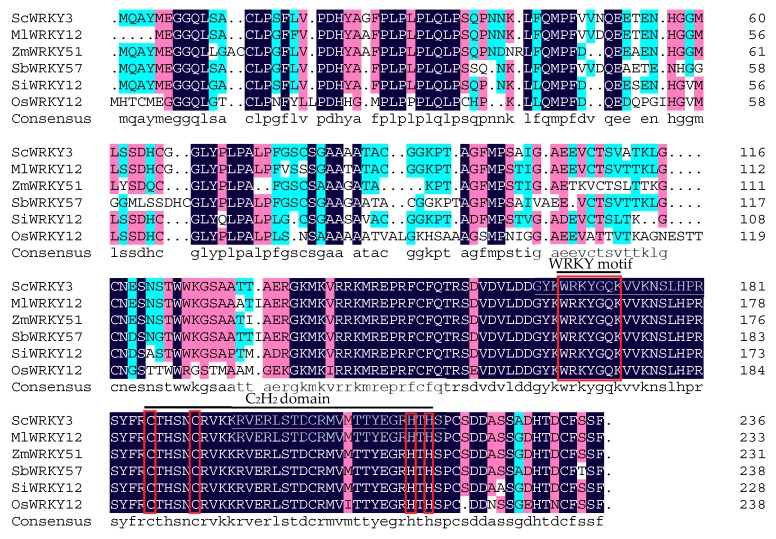

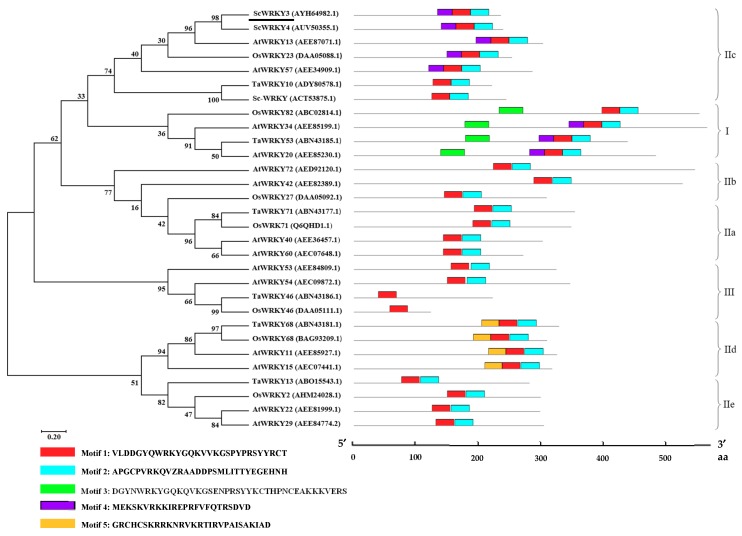

Amino acid sequence alignment (Figure S5) indicated that the similarity of ScWRKY3 to S. bicolor SbWRKY57 (XP_002452824.2), Miscanthus lutarioriparius MlWRKY12 (AGQ46321.1), Z. mays ZmWRKY51 (XP_020393361.1), S. italica SiWRKY12 (XP_004953301.1), O. sativa OsWRKY12 (XP_015624962.1) (all these accession numbers in brackets are from GenBank), sugarcane ScWRKY4 and Sc-WRKY were 93%, 93%, 87%, 87%, 66%, 53% and 24%, respectively. A conserved WRKY domain (WRKYGQK) and a conserved zinc-finger motif (CX4CX23HXH) at the C-terminus were found (Figure 2). The phylogenetic tree of sugarcane ScWRKY3, ScWRKY4, Sc-WRKY and WRKYs from other plant species demonstrated that WRKY proteins could be divided into three groups with no obvious distinction between monocots and dicots. ScWRKY3 was classified into group IIc, along with AtWRKY13, OsWRKY22, AtWRKY57, TaWRKY10, Sc-WRKY, and ScWRKY4 (Figure 3). MEME software prediction showed that all WRKYs except TaWRKY46 and OsWRKY46 contained motif 1 (WRKY domain) and motif 2 (zinc-finger domain). In addition, motif 3 (WRKY domain) and motif 4 (unknown domain) were detected in group I WRKYs. Some group IIc WRKYs, for example ScWRKY3, ScWRKY4, AtWRKY13, OsWRKY23 and AtWRKY57, contained motif 4. The WRKYs in group IId had their unique motif 5 (unknown domain) (Figure 3). On the whole, the phylogenetic analysis showed that most WRKYs within the same group generally had a similar structure.

Figure 2.

Amino acid sequence alignment of ScWRKY3 and WRKYs from other plant species by DNAMAN (version 6.0.3.99, Lynnon Biosoft) software. The amino acid sequences of Miscanthus lutarioriparius MlWRKY12 (AGQ46321.1), Zea mays ZmWRKY51 (XP_020393361.1), Sorghum bicolor SbWRKY57 (XP_002452824.2), Setaria italica SiWRKY12 (XP_004953301.1), and Oryza sativa OsWRKY12 (XP_015624962.1) are from GenBank. The black, pink, blue, and white colors indicate the homology level of conservation of the amino acid residues in the alignment at 100, ≥75, ≥50, and <50%, respectively. The sequences of the WRKY motif (WRKYGQK) and the C2H2 domain (CX4CX23HXH) are highlighted by the red rectangle.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree (left) and predicted conserved motifs (right) of ScWRKY3 protein and WRKYs from various plant species. The GenBank accession number of WRKY proteins follows the protein name. Ml, Miscanthus lutarioriparius; Sb, Sorghum bicolor; Zm, Zea mays; Si, Setaria italic; Os, Oryza sativa; and At, Arabidopsis thaliana. The unrooted tree is constructed by the Maximum Likelihood with bootstrapping (1000 iterations) using MEGA7.0 software. ScWRKY3 is underlined. The conserved domains were predicted by MEME Suite 5.0.2 software. The different-colored boxes named at the bottom represent conserved motifs. Gray lines represent the nonconserved sequences, and the position of each WRKY sequence is exhibited proportionally. The motif logo is shown in Figure S6.

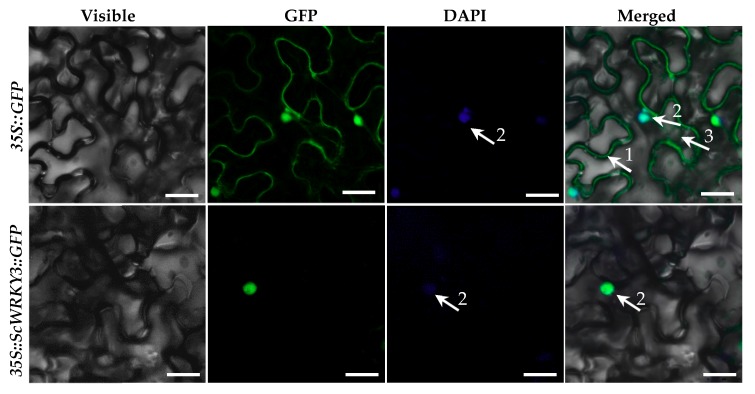

2.2. Subcellular Localization

The recombinant vector pMDC83-ScWRKY3-GFP was generated to investigate the subcellular distribution of ScWRKY3. We used 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI) staining as a nuclear marker. As shown in Figure 4, the green fluorescence of the control (35S::GFP) in N. benthamiana was distributed through the whole cell, including the plasma membrane, nucleus, and cytoplasm, while the fusion protein of ScWRKY3::GFP was only found in the nucleus, which was consistent with the software prediction.

Figure 4.

Subcellular localizations of 35S::GFP and 35S::ScWRKY3::GFP in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. The epidermal cells of N. benthamiana are used for capturing images of visible light, green fluorescence, blue fluorescence, and visible light merged with green and blue fluorescence. White arrows 1, 2, and 3 indicate plasma membrane, nucleus, and cytoplasm, respectively. Scale bar = 50 μm. 35S::GFP, the Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain carrying the empty vector pMDC83-GFP. 35S::ScWRKY3::GFP, the A. tumefaciens strain carrying the recombinant vector pMDC83-ScWRKY3-GFP. DAPI, 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole.

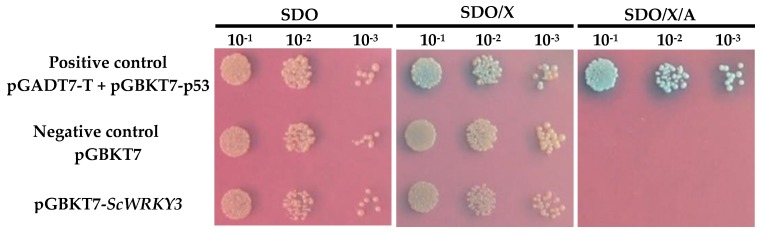

2.3. Transcription Activation Activity of ScWRKY3

The Y2H Gold-GAL4 yeast two-hybrid system was used to detect the transcriptional activation activity of ScWRKY3. As shown in Figure 5, yeast cells transformed with either the positive control pGADT7+pGBKT7-p53, the negative control pGBKT7-p53, or the recombinant plasmid pGBKT7-ScWRKY3 all grew well in SDO (SD/-Trp, SD minimal medium without tryptophan) medium plates, while only the positive control turned blue in SDO/X (SD/-Trp/X-α-Gal, SDO plates with X-α-D-galactosidase) medium plates. These results indicated that all the plasmids were successfully transfected into yeast strain Y2HGold. The GAL4-BD combined with ScWRKY3 protein can successfully express tryptophan but cannot activate the MEL1 gene in the presence of X-α-gal. After aureobasidin A (AbA) resistance screening, the yeast cells transformed with pGBKT7-ScWRKY3 and with the negative control did not activate the two reporter genes, AUR1-C and MEL1. However, the positive control did survive, and its X-α-gal detection system showed a blue color, indicating that the ScWRKY3 protein does not possess transcriptional activation activity. This protein showed no toxicity to the yeast strain Y2HGold. This result implies that the bait protein of ScWRKY3 can be used for yeast two-hybrid screening.

Figure 5.

Testing of the ScWRKY3 transactivation activity assay. SDO (SD/-Trp), synthetic dropout medium without tryptophan; SDO/X (SD/-Trp/X-α-Gal), synthetic dropout medium without tryptophan, but plus 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoxyl-α-D-galactopyranoside; SDO/X/A (SD/-Trp/X-α-Gal/AbA), synthetic dropout medium without tryptophan, but plus 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indoxyl-α-d-galactopyranoside and aureobasidin A.

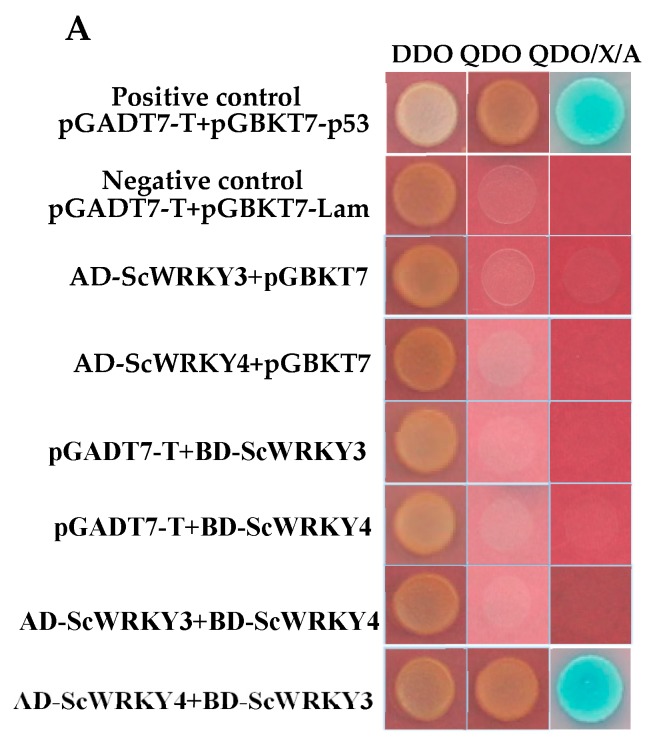

2.4. Interaction Between ScWRKY3 and ScWRKY4

As shown in Figure 6, all plasmid combinations grew normally on DDO (SD/-Leu/-Trp) plates. However, when transferred to QDO (SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp) and QDO/X/A (SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp/X-α-Gal/AbA) plates, only the AD-ScWRKY4+BD-ScWRKY3 combination and the positive control pGADT7-T+pGBKT7-p53 continued to grow and turned blue with X-α-gal detection. This indicates that ScWRKY4 may function downstream of ScWRKY3. Additionally, we have further proved the above results by bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC). When ScWRKY3 was fused to pUC-SPYNE (this fusion was named ScWRKY3-YFPN), and ScWRKY4 was fused to pUC-SPYCE (this fusion was named ScWRKY4-YFPC), a fluorescent complex was formed and was visualized in the nucleus of N. benthamiana leaf cells. While, when ScWRKY3 was fused to pUC-SPYCE (this fusion was named ScWRKY3-YFPC), and ScWRKY4 was fused to pUC-SPYNE (this fusion was named ScWRKY4-YFPN), no fluorescent complex was formed in N. benthamiana leaf cells. The results were consistent with those of yeast two-hybrid system and showed that there was an interaction between ScWRKY3 and ScWRKY4, and the specific protein complex was located in the nucleus.

Figure 6.

Interaction between ScWRKY3 and ScWRKY4 in yeast and in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. (A) The interaction between ScWRKY3 and ScWRKY4 was verified using a yeast two-hybrid system. A variety of BD and AD vectors were combined and transformed into GoldY2H yeast. Left to Right: Transformations were grown and screened on DDO (SD/-Leu/-Trp, SD medium without leucine and tryptophan), QDO (SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp, SD medium without adenine, histidine, leucine, or tryptophan), and QDO/X/A (SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp/X-α-Gal/AbA, QDO medium with X-α-D-Galactosidase and aureobasidin medium. (B) The bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) assay for the location determination of the interaction between ScWRKY3 and ScWRKY4. Scale bar = 50 μm. YFPC, YFPN, ScWRKY4-YFPC, ScWRKY4-YFPN, ScWRKY3-YFPC, and ScWRKY3-YFPN represent the plasmids pUC-SPYCE and pUC-SPYNE and the recombinant plasmids ScWRKY4-pUC-SPYCE, ScWRKY4-pUC-SPYNE, ScWRKY3-pUC-SPYCE and ScWRKY3-pUC-SPYNE, respectively.

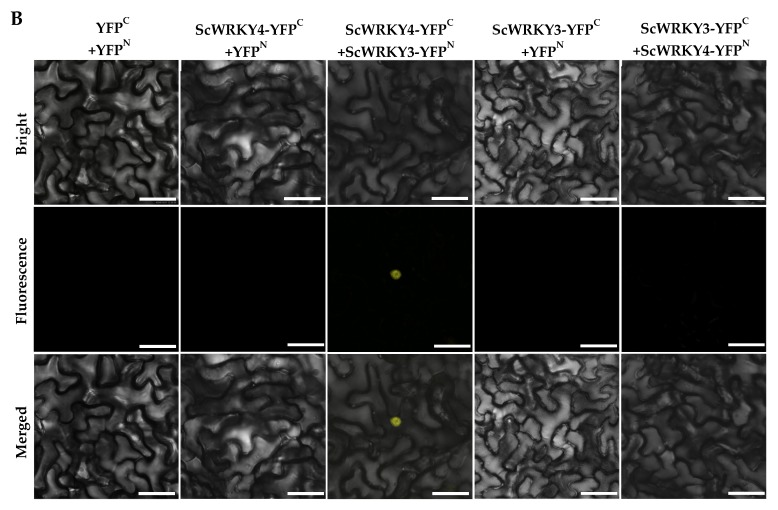

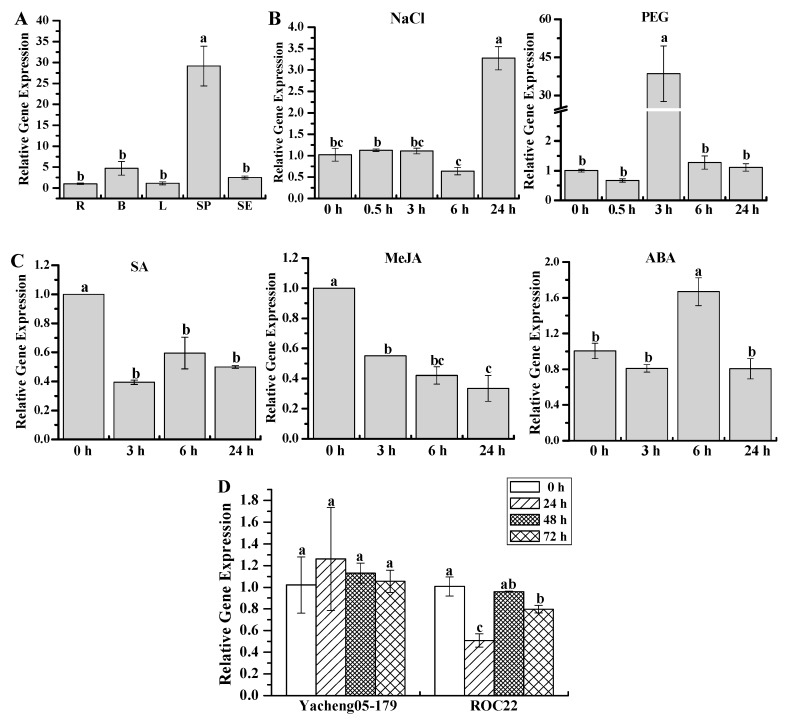

2.5. Gene Expression Patterns of ScWRKY3 in Response to Various Stress Conditions

The expression patterns of the ScWRKY3 gene in sugarcane tissues and under various stresses were investigated using real-time fluorescent quantitative PCR (qRT-PCR). The results indicated that ScWRKY3 was constitutively expressed in different sugarcane tissues, with the highest expression level in stem epidermis. It remained at lower expression levels in other tissues (root, bud, leaf, and stem pith) (Figure 7A). During the treatments with NaCl and PEG, the transcript of ScWRKY3 in ROC22 was remarkably up-regulated by 3.28-fold at 24 h and 38.57-fold at 3 h, respectively, and remained unchanged at other time points (Figure 7B). Moreover, the expression of ScWRKY3 in ROC22 was markedly down-regulated under both SA and methyl jasmonate (MeJA) treatments, but it was up-regulated under ABA stress with a 1.73-fold higher level than in the control (Figure 7C). These results indicated that the ScWRKY3 gene might have positive responses to ABA, PEG, and NaCl stimuli but a negative response to SA and MeJA. After infection by the smut pathogen, the expression level of ScWRKY3 was almost unchanged after 72 h in the smut-resistant cultivar Yacheng05-179 and during the period of 48–72 h in the smut-susceptible cultivar ROC22, while it was significantly down-regulated (0.76-fold) at 24 h in ROC22 (Figure 7D). This suggested that ScWRKY3 may play a role in the smut pathogen response.

Figure 7.

Gene expression assay of ScWRKY3. (A) Tissue-specific expression analysis of ScWRKY3 in different 10-month-old ROC22 tissues by qRT-PCR. The tissues (root, bud, leaf, stem pith, and stem epidermis) are represented by R, B, L, SP, and SE, respectively; (B) Gene expression patterns of ScWRKY3 in 4-month-old ROC22 plantlets under abiotic stress. NaCl, sodium chloride (simulating salt stress) (250 mM); PEG, polyethylene glycol (simulating drought treatment) (25.0%); (C) Gene expression patterns of ScWRKY3 in 4-month-old ROC22 plantlets under plant hormone stress. SA, salicylic acid (5 mM); MeJA, methyl jasmonate (25 μM); ABA, abscisic acid (100 μM); (D) Gene expression patterns of the ScWRKY3 gene after infection with smut pathogen. Yacheng05-179 is a smut-resistant Saccharum hybrid cultivar, and ROC22 is a smut-susceptible Saccharum hybrid cultivar. Data are normalized to the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) expression level. All data points are means ± standard error (n = 3). Bars superscripted by different lowercase letters indicate significant differences, as determined by Duncan’s new multiple range test (p-value < 0.05).

2.6. Transient Overexpression of ScWRKY3 in N. benthamiana Leaves

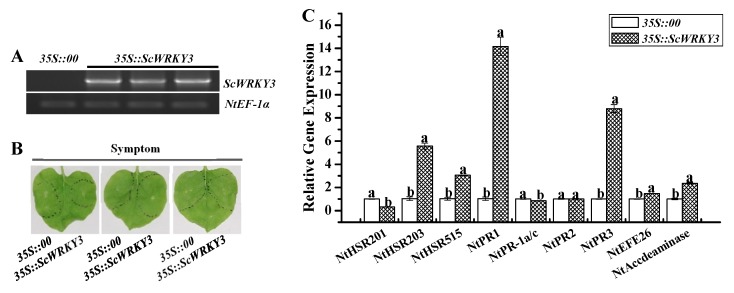

The ScWRKY3 gene was inserted into the plant overexpression vector, and was transformed into N. benthamiana leaves by the Agrobacterium tumefaciens-mediated method to analyze whether the target gene could induce a plant immune response. The transcripts of ScWRKY3 in N. benthamiana leaves were detected using a semi-quantitative PCR technique (Figure 8A). The phenotypic observation after injection for one day was shown in Figure 8B, and no significant difference in superficial characteristics was demonstrated between the experimental group and the control group. However, qRT-PCR results demonstrated that six immunity-associated marker genes, including the hypersensitive response (HR) marker genes, NtHSR203 and NtHSR515, the SA pathway related gene NtPR1, the JA pathway associated gene NtPR3, and two ethylene synthesis-dependent genes, NtEFE26 and NtAccdeaminase, were all up-regulated with a higher fold change range from 1.47 to 14.16 than the control (Figure 8C). These results suggest that transiently overexpressed ScWRKY3 may take part in the immune response in N. benthamiana leaves.

Figure 8.

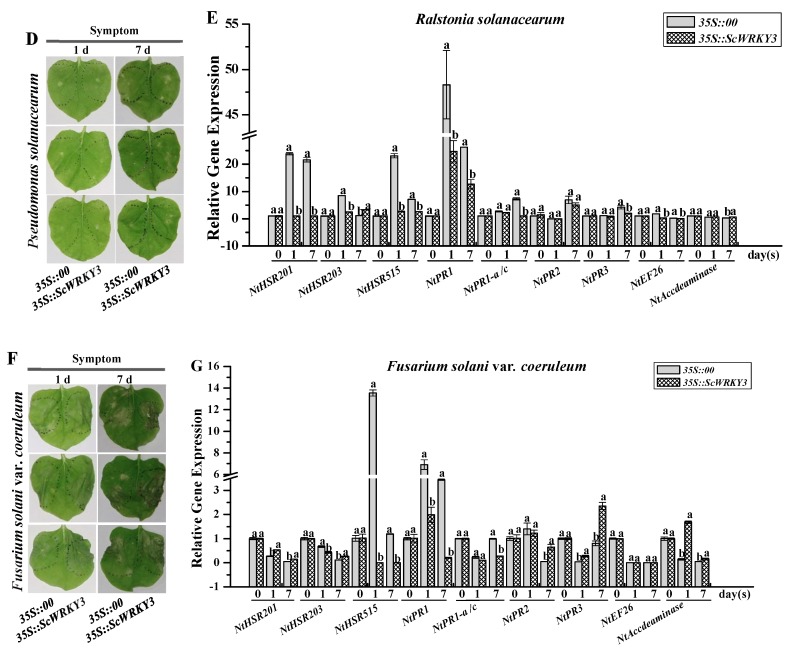

Effects of transient overexpression of ScWRKY3 in Nicotiana benthamiana leaves. (A) Semi-quantitative PCR analysis of ScWRKY3 in N. benthamiana leaves after one day of infiltration by Agrobacterium strain GV3101 carrying pEarleyGate 203-ScWRKY3 (35S::ScWRKY3) and the empty vector pEarleyGate 203 (35S::00). (B) Phenotype of N. benthamiana leaves after one day of agroinfiltration. (C) The transcript level of nine immunity-associated marker genes in the N. benthamiana leaves after one day of agroinfiltration. (D,F) Disease symptoms of N. benthamiana post-inoculation with Ralstonia solanacearum and Fusarium solani var. coeruleum are observed after one day and seven days of agroinfiltration. (E,G) The transcripts of nine immunity-associated marker genes in the N. benthamiana leaves after inoculation with R. solanacearum or F. solani var. coeruleum for one day and seven days. Data are normalized to the NtEF-1α expression level. All data points are means ± standard error (n = 3). Bars superscripted by different lowercase letters indicate significant differences, as determined by Duncan’s new multiple range test (p value < 0.05).

To detect the effect of ScWRKY3 in response to pathogen, the N. benthamiana leaves, were transformed with the control in the left half blade and with 35S::ScWRKY3 in the right half blade for one day. Then they were inoculated by the bacterial pathogen R. solanacearum. As shown in Figure 8D, there was a slight symptomatic difference between the control half-leaves and the 35S::ScWRKY3 half-leaves when injected with R. solanacearum for one day and seven days. Moreover, qRT-PCR results revealed that the HR marker genes NtHSR201 and NtHSR515 and the SA-related gene NtNPR1 all showed significantly lower expression in 35S::ScWRKY3-overexpressing N. benthamiana leaves after one day and seven days of R. solanacearum inoculation when compared to the control. No remarkable transcript difference or down-regulation of the SA-related gene NtPR-1a/c or the JA-associated genes NtPR2 and NtPR3 was observed in 35S::ScWRKY3 leaves when compared with controls. Compared to the control, the transcript abundance of NtHSR203 in 35S::ScWRKY3-overexpressing leaves was decreased at one day but increased at seven days post-agroinfiltration.

When the leaves of ScWRKY3-transiently-overexpressing N. benthamiana were inoculated by the fungal pathogen F. solani var. coeruleum for one day and seven days, a heavier wilting disease symptom was observed in the N. benthamiana leaves containing 35S::ScWRKY3 than in the control (Figure 8F). Additionally, in comparison with the control, NtHSR201, NtPR3, and NtAccdeaminase showed significantly higher expression, while NtHSR515 and NtNPR1 presented obviously lower expression in 35S::ScWRKY3-overexpressing leaves at one day or seven days after F. solani var. coeruleum infection. No statistically significant expression difference in NtPR-1a/c, NtPR2, or NtEFE26 was found at one day, while NtPR-1a/c was down-regulated, NtPR2 was up-regulated, and NtEFE26 was unchanged in 35S::ScWRKY3 leaves after seven days with F. solani var. coeruleum inoculation. The expression level of NtHSR203 in 35S::ScWRKY3 was lower at one day but higher at seven days after inoculation than in the control (Figure 8G).

These results demonstrated that in comparison with the transiently overexpressing pEarleyGate 203 vector, ScWRKY3 transient overexpression in N. benthamiana leaves significantly decreased the transcript abundance of NtHSR515, NtPR1, and NtPR-1a/c after R. solanacearum or F. solani var. coeruleum infection. It was anticipated that ScWRKY3 can negatively regulate the HR marker genes or SA signaling pathway-mediated genes to reduce the tolerance of N. benthamiana to pathogens.

3. Discussion

As one of the largest groups of TFs, the WRKY proteins have been found in a wide range of plant species since the initial WRKY cDNA was isolated from sweet potato [31]. Although sugarcane is an important bioenergy and cash crop [25], there are only three reports about WRKYs in sugarcane [26,27,28]. In this study, a novel sugarcane ScWRKY3 gene was isolated and identified. As reported, there is a functional similarity of WRKYs in the same or phylogenetically closely related group [2,3]. Phylogenetic tree analysis indicated that ScWRKY3 is a member of the group IIc WRKY proteins, along with Sc-WRKY [27] and ScWRKY4 [28] (Figure 3). This is helpful for further functional comparative studies on the same WRKY family members in sugarcane. The structure of TFs is usually composed of four functional domains, namely, the DNA binding domain, the transcriptional activation or repression domain, the oligomerization sites, and the nuclear localization signals [32]. These four components are the core regions that perform the functions of TFs or interact with the cis-acting elements in the promoter regions of various stress related genes [33]. In our study, ScWRKY3 protein had one WRKY domain, which is a DNA binding domain containing 60 amino acids. WRKY domain was mainly composed of motif 1 and motif 2 (Figure 3) and can bind specifically to the DNA sequence motif (T)(T)TGAC(C/T) which is known as the W-box and existed in many promoters of plant defense-related genes [6]. As showed by Wei et al. [10], subgroup IId WRKYs possess two basic amino acid sequences, including a RCHCSK[RK][RK]K[LN]R motif, which may function as a nuclear localization signal, and a KRxIxVPAISxKxAD motif. Similarly, the motif 5 (Figure 3) also contains these amino acid sequences. While further work is required to clarify the function of the other unknown motifs, such as the predicted motif 4 in Figure 3. Previous studies showed that the functions of the two WRKY domains in the group I WRKYs are different. The WRKY domain at the C-terminal can bind to their target DNA, while another WRKY domain at the N-terminal may be as the site where proteins interact with each other [8,12,15].

Subcellular localization analysis is valuable for determining the functions of proteins. The present study showed that the fusion protein of ScWRKY3::GFP was detected in the nucleus of N. benthamiana leaf cells (Figure 4), which was consistent with the software prediction results and previous studies on other plant WRKYs [28,34,35,36]. This indicated that ScWRKY3 may play a role as a nuclear-localized protein to regulate cellular processes.

Transcriptional activity analysis is important for the functional analysis of TFs [37]. Since the GAL4 yeast two-hybrid system was first discovered [38], this method has been increasingly used to study the interactions between WRKY proteins [39]. In this study, the full-length ScWRKY3 cDNA showed no auto-activation (Figure 5), so it could be used as the bait to screen interacting proteins in a yeast two-hybrid system. Post-translational modifications or interactions with cofactors are needed for ScWRKY3 protein to fulfill its function. Screening and identifying WRKY interacting proteins is important to reveal the role of WRKY in plant signal transduction [40,41]. It has been reported that WRKYs have the activities of self-regulation and mutual regulation, and they can form functional homo- or heterodimers among some WRKY proteins or interact with other functional proteins to play roles [4,5]. WRKY6 and WRKY22, which both belong to group II WRKYs in A. thaliana, interact with MPKl0 and MPK3/MPK6, respectively [42,43]. Previous studies also proved that AtWRKY30, AtWRKY53, AtWRKY54, and AtWRKY70, which all belong to group III of the WRKY proteins, have interactive effects in yeast [39]. Similarly, yeast two-hybrid and BiFC results showed that a fluorescent complex from ScWRKY3 and ScWRKY4 was formed (Figure 6B). This was visualized in the nucleus in N. benthamiana leaf cells, which indicated that there may be an interacting relationship between ScWRKY3 and ScWRKY4. In Arabidopsis, previous study indicated that WRKYs in the group IIb or group III could interact with themselves and with group IIa WRKYs, while group IId WRKYs could only interact with group IIa WRKY members [41]. Groups IIc ZmWRKY25 and ZmWRKY47 had interactions and may be involved in the response to drought stress by interacting with other WRKYs [15]. Besides, ZmWRKY39 was down-regulated under light drought stress and its phylogenetically closely related protein ZmWRKY106 showed a positive response to this stress, while they had up-regulated co-expression interaction under drought stress [15]. However, the nature of the interaction as well as the biological implications of this process between ScWRKY3 and ScWRKY4 requires further study.

WRKY genes are expressed differentially in different tissues of plants, which demonstrates that WRKY genes can be expressed in different physiological conditions and in different types of cells, and may regulate a series of life activities including growth, development, and morphological composition [35,40,44]. Twenty-eight CiWRKYs were detected in the roots, stems, and leaves of wild Caragana intermedia, and different CiWRKYs showed differential expression in various tissues. For example, CiWRKY69–1 had the highest expression level in roots, while CiWRKY40–1 and CiWRKY30 were mainly expressed in leaves [35]. Among the 37 A. thaliana WRKY genes reported by Bakshi et al. [45], 12 were specifically expressed in the mature zone of root cells, suggesting that these WRKY genes may be involved in the regulation of root cell maturation in A. thaliana. TaWRKY44, a WRKY gene of Triticum aestivum, was differentially expressed in all organs examined, including root, stem, leaf, pistil, and stamen, with the highest expression level in the leaves and the lowest expression level in the pistils [40]. It is known that ScWRKY4 is constitutively expressed in the root, bud, leaf, stem pith, and stem epidermis of sugarcane, with the highest expression level in the stem epidermis [28]. This was similar to the findings on tissue-specific expression of ScWRKY3 in the present study. Can the coexpression of ScWRKY3 and ScWRKY4 in the same tissue be tied together with their BiFC interaction results (Figure 6B)? Can they co-localize in the same organelle in the same tissue? These remain to be validated by future research, for example, only if we obtain the promoters specific to ScWRKY3 and ScWRKY4 respectively, can we check that if they co-localize in the same organelle in the same tissue. WRKY TFs are critical for signal transduction, plant growth and stress responses [44]. Salt and drought, the two representative abiotic stresses, adversely affect the growth and development of plants, but the response can be resisted by activating the ABA signal transduction pathway to induce the expression of a series of stress-responsive genes [46]. AtWRKY1 played a negative role in ABA-mediated drought resistance, and the AtWRKY1 knockout mutant could enhance the drought tolerance of A. thaliana [47]. In the OsWRKY11 knockout mutant, drought responsive genes were induced to enhance the drought tolerance of rice [36]. The present study showed that the expression of ScWRKY3 was increased by PEG, NaCl, and exogenous ABA. Previous studies also determined that Sc-WRKY and ScWRKY4 showed up-regulated expression levels under PEG and NaCl treatments [27,28]. Furthermore, under ABA stress, the transcript of ScWRKY4 was remarkably up-regulated by 1.59-, 2.87-, and 1.26-fold at 0.5 h, 6 h, and 24 h higher than the control, respectively [28]. These results suggest that ScWRKY3 and ScWRKY4 may participate in sugarcane resistance to drought and salt stresses which may be mediated through ABA signaling. Similar to the expression characteristics seen in group II WRKYs of other plants, the expression level of AtWRKY57 was remarkably up-regulated in drought conditions. This occurred through the direct activation of the expression of an important functional gene (AtNCED3) in the ABA synthesis pathway, which enhanced the tolerance of A. thaliana to drought stress [48].

Plants have evolved at least two sets of biochemical defenses to protect themselves against external challenges [49]. One defense response, caused by infection of pathogenic bacteria, initiates a localized hypersensitive reaction to confine the injured site and to prevent further infection of pathogens. This is known as systemic acquired resistance (SAR) [50]. The other response is mainly activating the expression of defense genes through various signal molecules to exhibit resistance in plants. The signal transduction pathways related to this defense response may be mediated by SA, JA, or ABA [51,52]. Previous studies indicated that the WRKY genes of group IIc are related to plant immunity. For instance, AtWRKY28 and AtWRKY75 can be induced by infection with Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in connection with SA- and JA/ET-mediated defense signaling pathways [53]. Overexpression of rice WRKY89 increased the expression level of SA and enhanced the resistance to rice blast fungus [54]. AtWRKY57 is negatively associated with resistance to Botrytis cinerea in A. thaliana by regulating the expression of JA pathway-related genes [49]. OsWRKY13 enhances the resistance of rice to X. oryzae pv. oryzae and M. grisea [55,56]. In the present study, ScWRKY3 was down-regulated by smut pathogen in the smut-susceptible cultivar ROC22 at 24 h, while it was almost unchanged in the smut-resistant cultivar Yacheng05-179. Conversely, Wang et al. [28] showed that the expression of ScWRKY4 was quite stable in ROC22 but was down-regulated in Yacheng05-179 under the stress of smut pathogen. Liu et al. [27] found that the expression of Sc-WRKY was remarkably up-regulated at 24 and 60 h after infection by smut pathogen treatment in sugarcane FN22. Moreover, ScWRKY3 was down-regulated under SA and MeJA treatments, which was opposite to the expression patterns of ScWRKY4 and Sc-WRKY [27,28]. The results revealed that ScWRKY3 might be a negative regulatory gene in the sugarcane response to smut pathogen. This can be further proved by antimicrobial test in more stable overexpression and knockout plants. In Arabidopsis, AtWRKY25 gene was proved to play a negative regulatory role in the SA-mediated defense response to Pseudomonas syringae [57] but a positive regulatory role in response to NaCl stress [58]. Yokotani et al. [59] demonstrated that overexpression of OsWRKY76 in rice plants suppressed the induction of defense related genes after inoculation with blast fungus (Magnaporthe oryzae) but up-regulated the expressions of abiotic stress-associated genes using microarray analysis. It is therefore possible for WRKY genes to play opposite roles in biotic resistance and abiotic tolerance. In the future, genetic transformations can be done to further our understanding on the responses of ScWRKY genes to biotic and abiotic stresses. In addition, whether there are sequence differences in the promoter regions of the ScWRKY genes from different sugarcane cultivars which may cause differences in gene expression patterns for the biotic or abiotic stress need further investigation.

As Liu et al. [60] proved, overexpression of the Gossypium hirsutum GhWRKY25 in N. benthamiana is involved in the regulation of expression of multiple defense-associated marker genes, including the SA-, ET-, and JA-mediated genes, to decrease the resistance to the fungal pathogen B. cinerea. GhWRKY40 has been revealed to be inducible by stress from the bacterial pathogen R. solanacearum, and GhWRKY40 expression was up-regulated by SA, MeJA, and ET [61]. When GhWRKY40 was transiently overexpressed in N. benthamiana leaves, most of the resistance-associated genes, including the SA-, ET-, JA-, and HR-responsive genes, were down-regulated after infection with R. solanacearum, which indicated that overexpression of GhWRKY40 reduces the tolerance to R. solanacearum [61]. A. thaliana WRKY27 negatively regulated resistance genes during infection with the pathogen R. solanacearum, and the symptom development in R. solanacearum appeared earlier than in the mutant wrky27-1 plants, which lacks the function of WRKY27 [62]. In this study, most of the immunity-associated marker genes, including the HR-, SA-, JA-, and ET-related genes, were up-regulated when ScWRKY3 was transiently overexpressed in N. benthamiana, suggesting that ScWRKY3 may play a role in the plant immune response. After infection with the bacterial pathogen R. solanacearum, most of the detected immunity-associated marker genes, including the HR marker genes NtHSR201 and NtHSR515, the SA-related genes NtPR-1a/c and NtNPR1, and the JA-associated gene NtPR3, were lower in the 35S::ScWRKY3 overexpressing leaves than in the control, revealing that ScWRKY3 may play a negative role in the response to the bacterial pathogen R. solanacearum. After F. solani var. coeruleum infection, the wilting disease symptoms were greater in 35S::ScWRKY3 leaves than in the control. The qRT-PCR results showed that the transcript abundance of JA- and ET-related genes was remarkably higher, but the SA-related genes were evidently reduced in 35S::ScWRKY3 leaves compared to their levels in the control. These results indicated that there was a crosstalk between JA-/ET-related genes and SA-related genes in the response to the fungal pathogen F. solani var. coeruleum when ScWRKY3 was overexpressed in N. benthamiana.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

In China, ROC22 has been the main sugarcane cultivar grown for the past 20 years and encompasses approximately 60% of the total sugarcane cultivated area. ROC22 is a Saccharum hybrid cultivar which is susceptible to smut disease and results in a poor ratoon performance. Yacheng05-179, an intergeneric hybrid (BC2) with smut resistant properties, is generated from S. officinarum × S. arundinaceum. In this study, ROC22 and Yacheng05-179 were used as plant materials and collected from the Key Laboratory of Sugarcane Biology and Genetic Breeding, Ministry of Agriculture, Fuzhou, China.

To analyze the tissue-specific expression level of the target gene, nine healthy and uniform 10-month-old ROC22 plants were randomly selected from one field. The white root, bud, +1 leaf, stem pith, and stem epidermis were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at -80 °C until extraction of total RNA. Each sample contained three biological replicates.

For biotic treatment, the robust and healthy stems of 10-month-old ROC22 and Yacheng05-179 were harvested and soaked in water for germination at 32 °C. Then the two-bud setts of both sugarcane cultivars were inoculated with 0.5 µL suspensions of 5 × 106 smut spores/mL (plus 0.01% (v/v) Tween-20), while the control was inoculated with aseptic water in 0.01% (v/v) Tween-20 [63]. The treated samples were cultured at 28 ± 1 °C in a photoperiod of 16-h light and 8-h darkness. Three biological replicates were set, and five buds were randomly chosen at 0 h, 24 h, 48 h, and 72 h for each biological replicate, respectively.

For abiotic and hormone stimuli, healthy and uniform approximately 4-month-old ROC22 plantlets were transferred to water for one week and then treated with six different exogenous stresses. Two groups were separately cultured in aqueous solutions of 250 mM NaCl and 25% PEG 8000, and the leaves were sampled at 0, 0.5, 3, 6, and 24 h, respectively [63,64,65]. The other three groups were sprayed with 100 μM ABA, 5 mM SA in 0.01% (v/v) Tween-20 and 25 μM MeJA for 0, 3, 6, and 24 h, respectively [63,64,65]. Each treatment was prepared with three biological replicates that contained three plants. All collected samples were immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen and kept at −80 °C until use.

4.2. RNA Extraction and First-strand cDNA Synthesis

The total RNAs of all the samples were extracted with TRIzol® reagent (Invitrogen, Shanghai, China). The RNA quality was determined by 1.0% agarose gel electrophoresis and measured at wavelengths of 260 and 280 nm using a spectrophotometer (NanoVueplus, GE, USA). The residual DNA was removed by DNase I (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). The RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Fermentas, Shanghai, China) was used to synthesize the first-strand cDNA from ROC22 and Yacheng05-179 leaves which was treated as templates for cloning the target gene. Prime-Script™ RT Reagent Kit (Perfect Real Time) (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China) was used to synthesize the first-strand cDNA of the other samples for expression profile analysis.

4.3. Cloning, Sequencing, and Bioinformatic Analysis of the ScWRKY3 Gene

A gene which codes for a predicted WRKY transcriptional regulator named ScWRKY3 was screened from our previous transcriptome data of sugarcane infected by smut fungus [29]. The specific amplification primers (Table S2) were designed using National Center of Biotechnology Information (NCBI) online software (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/tools/primer-blast/). The reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) system contained 1.0 µL cDNA template, 1.0 μL each of the forward and reverse primers (10 μM), 2.5 μL 10× ExTaq buffer (Mg2+ plus), 2.0 μL dNTPs (2.5 mM), and 0.125 μL ExTaq enzyme (5.0 U/μL) (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China), and 17.375 μL ddH2O. The RT-PCR reaction conditions were as follows: 94 °C for 4 min; 35 cycles of 94 °C for 30 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 1 min 30 s; and 72 °C for 10 min. The amplified fragment, which had been gel-purifed using a Gel Extraction Kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China), was linked to the pMD19-T vector (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China) and transformed into Escherichia coli strain DH5α cells. The positive clones were selected for sequencing (Biosune, Fuzhou, China).

The sequence of the ScWRKY3 gene was analyzed using the ORF Finder (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/orffinder/) and a conserved domains program (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Structure/cdd/wrpsb.cgi) [66]. ProtParam (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/) [67] and NPS@ srever (https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=/NPSA/npsa_hnn.html) [68] were used for analyzing the primary structure and secondary structure of the ScWRKY3 protein, respectively. The online programs SignalP 4.1 Server (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/SignalP/) [69,70], TMHMM Server v. 2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/) [71], and Euk-mPLoc 2.0 Server (http://www.csbio.sjtu.edu.cn/bioinf/euk-multi-2/) [30] were used to predict the signal peptide, the transmembrane domain, and the subcellular localization of the target protein, respectively. The BLASTp program (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi?PROGRAM=blastp&PAGE_TYPE= BlastSearch&LINK_LOC=blasthome) in NCBI was used to find the homologous amino acid sequences from other plants. The multiple alignment was performed using DNAMAN 6.0.3.99 software. Then the MEGA 7.0 software [72] with the Maximum Likelihood (ML) (1000 BootStrap) method was used to construct the unrooted phylogenetic tree of ScWRKY3 with sugarcane Sc-WRKY, ScWRKY4, and WRKY proteins from Arabidopsis thaliana [14] and other plants [13,73]. The online software MEME Suite 5.0.2 (http://meme.sdsc.edu/meme/intro.html) [73] was used to build the logo representations of the conservative domain and the rest of the alignment.

4.4. Subcellular Localization

The complete coding region of ScWRKY3 without a stop codon was amplified using the primers ScWRKY3-Gate-F and ScWRKY3-Gate-R (Table S2), which were designed based on the sequences of ScWRKY3 and the Gateway® donor vector of pDONR221. The gel-purified product was linked into pDONR221 using the Gateway BP ClonaseTM II enzyme mix (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and transformed into DH5α cells and sequenced (Biosune, Fuzhou, China). The Gateway LR ClonaseTM II enzyme mix (Invitrogen) was used to ligate pDONR221-ScWRKY3 into the subcellular localization vector pMDC83-GFP [74]. GV3101 cells, carrying the recombinant vector pMDC83-ScWRKY3-GFP or the pMDC83-GFP vector were inoculated into LB liquid medium supplemented with 35 μg/mL rifampicin and 50 μg/mL kanamycin, and shaken overnight in an incubator at 200 rpm and 28 °C. Subsequently, Murashige and Skoog (MS) liquid medium was used to dilute the cell density of the Agrobacterium solutions to an OD600 of 0.8. This was supplemented with 200 μM acetosyringone and cultured in the dark for 30 minutes. Then the Agrobacterium solutions were injected into the leaves of eight-leaf stage N. benthamiana using a 1.0 mL sterilized syringe [75,76]. After two days of infiltration, the treated leaves were collected and stained with 1.0 µg/mL DAPI solution in dark conditions for one h. The subcellular localization result was observed using a Leica Microsystems microscope (model Leica TCS SP8, Mannheim, Germany) with a 10 × lens, a chroma GFP filter set for EGFP (excitation at 488 nm), and a DAPI filter set for chromatin (excitation at 458 nm) [60].

4.5. Analysis of Transcriptional Activation of ScWRKY3 in Yeast Cells

To analyze the transcriptional activation of ScWRKY3, the Y2HGold-GAL4 yeast two hybrid system (containing four reporter genes, including AUR1-C, HIS3, ADE2, and MEL1) was used following the manufacturer’s instructions for the Matchmaker Gold yeast two-hybrid system [49]. The ScWRKY3 gene was PCR-amplified from pMD19-T-ScWRKY3 using primers ScWRKY3-BD-F and ScWRKY3-BD-R (Table S2). The gel-purified product was double-digested with Nde I and BamH I enzymes, as was the plasmid pGBKT7. Then the recombinant plasmid pGBKT7-ScWRKY3 was constructed using T4 DNA ligase (5 U/µL) (Thermo Fisher, Shanghai, China). The pGBKT7 vector, containing the nutritional screening marker gene TRP1, was used as a negative control. Plasmids of pGBKT7-53+pGADT7-T have been proven to bind the 53 protein and the T protein in yeast cells. The hybrid vector can activate the reporter gene AUR1-C on a plate that contains the AbA antibiotics, so it was used as the positive control. The empty vector plasmid pGBKT7 and plasmids pGBKT7-53+pGADT7-T and pGBKT7-ScWRKY3 were transformed into yeast strain Y2HGold following the manufacturer’s protocol for Y2HGold Chemically Competent Cells (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China). The positive colonies were screened from selective medium plates for transferring onto the SDO (SD/-Trp, SD minimal medium without tryptophan), the SDO/X (SD/-Trp/X-α-Gal, SDO plates with X-α-D-Galactosidase), and the SDO/X/A (SD/-Trp/X-α-Gal/AbA, SDO/X plates with aureobasidin A) plates, respectively. Then the transcriptional activation activities were calculated by observing and imaging the growth conditions of the yeast cells after incubating for 2–3 days in a 29 °C incubator.

4.6. Analysis of Interaction Between ScWRKY3 and ScWRKY4

Transcriptional activation analysis in this study and a previous study [28] showed that ScWRKY3 and ScWRKY4 (GenBank Accession No. AUV50355.1) did not possess transcriptional activation activity, and the bait protein has no toxic effect on the yeast strain Y2HGold. Hence, the interacting relationship between ScWRKY3 and ScWRKY4 was identified by a yeast two-hybrid system and BiFC analysis. In the yeast two-hybrid system, AD-ScWRKY3 or AD-ScWRKY4 was used as a prey vector, and BD-ScWRKY4 or BD-ScWRKY3 was used as a bait vector, respectively. A double-enzyme digestion method was used for bait vector and prey vector construction. The specific primers with corresponding restriction enzyme sites are shown in Table S2. pGADT7-T was used as prey control, and pGBKT7-p53 or pGBKT7-Lam was used as the positive or negative bait control, respectively. These combination constructs, including the positive control pGADT7-T + pGBKT7-p53, the negative control pGADT7-T + pGBKT7-Lam, AD-ScWRKY4 + pGBKT7, AD-ScWRKY3 + pGBKT7, pGADT7-T + BD-ScWRKY3, pGADT7-T + BD-ScWRKY4, AD-ScWRKY3 + BD-ScWRKY4, or AD-ScWRKY4 + BD-ScWRKY3, were co-transformed into yeast strain Y2HGold following the manufacturer’s protocol for Y2HGold Chemically Competent Cells (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China). Subsequently, the transformed yeast cells were selected using yeast selective medium DDO (SD/-Leu/-Trp) to detect whether all the plasmids were successfully transfected into the yeast strain Y2HGold. Then the interaction between ScWRKY3 and ScWRKY4 was detected using QDO (SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp) and QDO/X/A (SD/-Ade/-His/-Leu/-Trp/X-α-Gal/AbA) medium [64]. For BiFC vector construction, we used the Gateway method [77]. The coding sequences of ScWRKY3 and ScWRKY4 were amplified and linked into the non-fluorescent fragment in the pUC-SPYNE or pUC-SPYCE vector through LR-recombination using Gateway primers (Table S2). The two cooperating plasmids were transformed into the N. benthamiana leaves using the Agrobacterium-mediated method [78,79]. After five days of infiltration, the presence of fluorescence from yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) was observed using Leica Microsystems (model Leica TCS SP8, Mannheim, Germany) with a 10 × lens and a YFP filter (excitation at 561 nm).

4.7. Expression Patterns of ScWRKY3 in Sugarcane Tissues under Various Stresses

For the expression pattern analysis of ScWRKY3 in sugarcane tissues (root, bud, leaf, stem pith, and stem epidermis) and in response to various stresses (NaCl, PEG, SA, MeJA, and ABA), the qRT-PCR primers ScWRKY3-QF/R (Table S2) were designed using the Beacon Designer V8.14 software. Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (GenBank Accession Number: CA254672) was used as the reference gene (Table S2). An ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) and a SYBR Green PCR Master Mix Kit (Roche, Shanghai, China) were used for qRT-PCR analysis. The qRT-PCR reaction system was subjected to 50 °C for 2 min, 95 °C for 10 min, 95 °C for 15 s, and 59 °C for 1 min, for 40 cycles. A melting curve analysis was performed at 95 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 1 min, 95 °C for 15 s, and 60 °C for 30 s. Each sample was set up for triplicate technical replicates, and sterile water was used as the negative control template. The 2−∆∆CT method [80], DPS 9.50 software, and Origin 8 software were adopted to calculate the relative expression of the target gene (Tables S3–S6), to analyze the significance level of the experimental data, and to structure the histogram, respectively. To reduce the effects of mechanical injury on the expression of the target gene in the inoculation test with the smut pathogen, the relative expression level of the ScWRKY3 gene was determined by subtracting the expression of the sterile water at the corresponding time according to Su et al. [81].

4.8. Transient Expression of ScWRKY3 in N. benthamiana

The Gateway LR ClonaseTM II enzyme mix (Invitrogen) was used to ligate pDONR221-ScWRKY3, as mentioned above, into the overexpression vector of pEarleyGate 203 [82]. The plasmid of pEarleyGate 203-ScWRKY3 was transformed from the Gateway LR reaction into A. tumefaciens strain GV3101, while the pEarleyGate 203 vector which was transformed into GV3101 alone was used as a control. GV3101 cells were shaken overnight in LB liquid medium supplemented with 35 μg/mL rifampicin and 50 μg/mL kanamycin at 200 rpm and 28 °C. The Agrobacterium solutions were collected and resuspended to OD600 = 0.8 using the MS liquid medium and supplemented with 200 μM acetosyringone. Then the Agrobacterium suspensions were injected into the lower epidermis of the eight-leaf stage of N. benthamiana leaves using a 1.0 mL sterilized syringe and cultured at 28 °C with a photoperiod of 16-h light and 8-h darkness [76]. Each group of the injected leaves was collected for RNA extraction to analyze the expression level of ScWRKY3 in N. benthamiana by semi-quantitative PCR with the specific primer ScWRKY3-Gate-F/R (Table S2). The NtEF-1α (GenBank Accession No. D63396) gene was used as the reference gene. The semi-quantitative PCR program was set as: 94 °C, 4 min; 94 °C, 30 s; 65 °C, 30 s; 72 °C, 1 min plus 30 s; 35 cycles; and 72 °C, 10 min. Two important tobacco pathogens, including the bacterial pathogen of R. solanacearum and the fungal pathogen of F. solani var. coeruleum, were cultured overnight in potato dextrose water (PDW) liquid medium at 200 rpm and 28 °C. Then the two cultured pathogen cells were separately injected into the 1-day overexpressing N. benthamiana leaves after being diluted to OD600 = 0.6 using 10 mM magnesium chloride (MgCl2) solution. All treated plants were maintained for one week at 28 °C with a photoperiod of 16-h light/8-h darkness to track the changes in leaf symptoms and to analyze the relative transcript level of nine tobacco immunity-associated marker genes, including the HR marker genes NtHSR201, NtHSR203, and NtHSR515; the SA-related genes NtPR-1a/c and NtNPR1; the JA-associated genes NtPR2 and NtPR3; and the ET synthesis-dependent genes NtEFE26 and NtAccdeaminase (Tables S2 and S7–S9) [83,84]. All the treatments were carried out in three replicates. For representational observation, Agrobacterium suspensions carrying the vector pEarleyGate 203 and the recombinant vector pEarleyGate 203-ScWRKY3 were injected into the left and right side of each selected N. benthamiana leaf, respectively.

5. Conclusions

In this study, a novel ScWRKY3 gene was isolated from sugarcane and functionally characterized. ScWRKY3 belongs to group IIc of the WRKY family as a nucleoprotein, with no auto-activation. It has an interaction with another group IIc sugarcane WRKY protein, ScWRKY4, however the interaction mechanism and its corresponding function need further investigation. ScWRKY3 may participate in sugarcane resistance to drought and salt stimuli, and this resistance may be mediated by ABA signaling pathways. The transcript abundance of ScWRKY3 was stable in the smut-resistant cultivar Yacheng05-179, while it was down-regulated in the smut-susceptible cultivar ROC22 at 24 h, during inoculation with S. scitamineum. In addition, ScWRKY3 showed a negative regulatory effect on the bacterial pathogen R. solanacearum and the fungal disease F. solani var. coeruleum in 35S::ScWRKY3-overexpressing N. benthamiana. These results may be useful for the functional identification of the WRKY family in sugarcane and good for the interaction analysis of ScWRKY3 with other WRKY proteins or other functional proteins.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials can be found at http://www.mdpi.com/1422-0067/19/12/4059/s1, Figure S1: Nucleic acid sequences alignment of ScWRKY3 in ROC22 and Yacheng05-179; Figure S2. Secondary structure prediction of ScWRKY3; Figure S3. Signal peptide and transmembrane domain prediction of ScWRKY3; Figure S4. Subcellular localization prediction of ScWRKY3; Figure S5. Amino acid sequences alignment of ScWRKY3 and other WRKYs; Figure S6. The logo of predicted conserved motifs in the WRKYs; Table S1. Primary structure analysis of ScWRKY3; Table S2. Primers used in this study; Table S3. Raw calculations of tissue-specific expression of ScWRKY3 in different 10-month-old ROC22 tissues by qRT-PCR; Table S4. Raw calculations of gene expression patterns of ScWRKY3 in 4-month-old ROC22 plantlets under abiotic stress; Table S5. Raw calculations of gene expression of ScWRKY3 in 4-month-old ROC22 plantlets under plant hormone stress; Table S6. Raw calculations of expression of the ScWRKY3 gene after infection with smut pathogen; Table S7. Raw calculations of the transcript level of nine immunity-associated marker genes in the Nicotiana benthamiana leaves after one day of agroinfiltration; Table S8. Raw calculations of the transcripts of nine immunity-associated marker genes in the Nicotiana benthamiana leaves after inoculation with Ralstonia solanacearum for one day and seven days; Table S9. Raw calculations of the transcripts of nine immunity-associated marker genes in the Nicotiana benthamiana leaves after inoculation with Fusarium solani var. coeruleum for one day and seven days.

Author Contributions

L.W., Y.S., and Y.Q. conceived and designed the research. L.W. and X.Z. prepared the materials. L.W., F.L., X.Z., W.W., T.S., Y.C., M.D., and S.Y. conducted the experiments. L.W., F.L., and X.Z. analyzed the data. L.W. wrote the manuscript. Y.S., Y.Q., and L.P. helped to revise the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31101196, 31671752, and 31501363), the Research Funds for Distinguished Young Scientists in Fujian Provincial Department of Education (SYC-2017), the Special Fund for Science and Technology Innovation of Fujian Agriculture and Forestry University (KFA17267A), and the China Agriculture Research System (CARS-17).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ulker B., Somssich I.E. WRKY transcription factors: From DNA binding towards biological function. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2004;7:491–498. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jiang J.J., Ma S.H., Ye N.H., Jiang M., Cao J.S., Zhang J.H. WRKY transcription factors in plant responses to stresses. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2017;59:86–101. doi: 10.1111/jipb.12513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singh K.B., Foley R.C., Oñatesánchez L. Transcription factors in plant defense and stress responses. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002;5:430–436. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00289-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chen L.G., Song Y., Li S.J., Li S.J., Zhang L.P., Zou C.S., Yu D.Q. The role of WRKY transcription factors in plant abiotic stresses. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1819:120–128. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rushton P.J., Somssich I.E., Ringler P., Shen Q.J. WRKY transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2010;15:247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eulgem T., Rushton P.J., Robatzek S., Somssich I.E. The WRKY superfamily of plant transcription factors. Trends Plant Sci. 2000;5:199–206. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(00)01600-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mohanta T.K., Park Y.H., Bae H. Novel genomic and evolutionary insight of WRKY transcription factors in plant lineage. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:37309. doi: 10.1038/srep37309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen F., Hu Y., Vannozzi A., Wu K.C., Cai H.Y., Qin Y., Mullis A., Lin Z.G., Zhang L.S. The WRKY transcription factor family in model plants and crops. Plant Sci. 2018;36:1–25. doi: 10.1080/07352689.2018.1441103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramamoorthy R., Jiang S.Y., Kumar N., Venkatesh P.N., Ramachandran S. A comprehensive transcriptional profiling of the WRKY gene family in rice under various abiotic and phytohormone treatments. Plant. Cell Physiol. 2008;49:865–879. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei K., Chen J., Chen Y.F., Wu L.J., Xie D.X. Multiple-strategy analyses of ZmWRKY subgroups and functional exploration of ZmWRKY genes in pathogen responses. Mol. Biosyst. 2012;8:1940–1949. doi: 10.1039/c2mb05483c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Muthamilarasan M., Bonthala V.S., Khandelwal R., Jaishankar J., Shweta S., Nawaz K., Prasad M. Global analysis of WRKY transcription factor superfamily in Setaria identifies potential candidates involved in abiotic stress signaling. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:910. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pandey S.P., Somssich I.E. The role of WRKY transcription factors in plant immunity. Plant Physiol. 2009;150:1648–1655. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.138990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mangelsen E., Kilian J., Berendzen K.W., Kolukisaoglu U.H., Harter K., Jansson C., Wanke D. Phylogenetic and comparative gene expression analysis of barley (Hordeum vulgare) WRKY transcription factor family reveals putatively retained functions between monocots and dicots. BMC Genomics. 2008;9:194. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wei X.A., Yao W.J., Jiang T.B., Zhou B.R. Identification of WRKY gene in response to abiotic stress from WRKY transcirption factor gene family of Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Northeast. For. Univ. 2016;44:45–48. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang T., Tan D., Zhang L., Zhang X., Han Z. Phylogenetic analysis and drought-responsive expression profiles of the WRKY transcription factor family in maize. Agric. Gene. 2017;3:99–108. doi: 10.1016/j.aggene.2017.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu J., Chen J.B., Wang L.F., Wang S.M. Genome-wide investigation of WRKY transcription factors involved in terminal drought stress response in common bean. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:380. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.00380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qiu Y.Q., Jing S.J., Fu J., Li L., Yu D.Q. Cloning and analysis of expression profile of 13 WRKY genes in rice. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2004;49:2159–2168. doi: 10.1360/982004-183. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu H.L., Ni Z.F., Yao Y.Y., Guo G.G., Sun Q.X. Cloning and expression profiles of 15 genes encoding WRKY transcription factor in wheat (Triticum aestivem L.) Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 2008;18:697–705. doi: 10.1016/j.pnsc.2007.12.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dong J., Chen C.H., Chen Z.X. Expression profiles of the Arabidopsis WRKY gene superfamily during plant defense response. Plant Mol. Biol. 2003;51:21–37. doi: 10.1023/A:1020780022549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim K.C., Lai Z., Fan B., Chen Z. Arabidopsis WRKY38 and WRKY62 transcription factors interact with histone deacetylase 19 in basal defense. Plant Cell. 2008;20:2357–2371. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.055566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu D.L., Leib K., Zhao P.Y., Kogel K.H., Langen G. Phylogenetic analysis of barley WRKY proteins and characterization of HvWRKY1 and repressors of the pathogen-inducible gene HvGER4c. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 2014;289:1331–1345. doi: 10.1007/s00438-014-0893-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Peng Y., Bartley L.E., Chen X.W., Dardick C., Chern M., Ruan R., Canlas P.E., Ronald P.C. OsWRKY62 is a negative regulator of basal and Xa21-mediated defense against Xanthomonas orvzae pv. orvzae in rice. Mol. Plant. 2008;1:446–458. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssn024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Berri S., Abbruscato P., Faivre-Rampant O., Brasileiro A.C., Fumasoni I., Satoh K., Kikuchi S., Mizzi L., Morandini P., Pè M.E., et al. Characterization of WRKY co-regulatory networks in rice and Arabidopsis. BMC Plant Biol. 2009;9:120. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-9-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Banerjee A., Roychoudhury A. WRKY proteins: Signaling and regulation of expression during abiotic stress responses. Sci. World J. 2015:807560. doi: 10.1155/2015/807560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen R.K., Xu L.P., Lin Y.Q. Modern Sugarcane Genetic Breeding. China Agriculture Press; Beijing, China: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lambais M.R. In silico differential display of defense-related expressed sequence tags from sugarcane tissues infected with Diazotrophic endophytes. Genet. Mol. Biol. 2001;24:103–111. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572001000100015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu J.X., Que Y.X., Guo J.L., Xu L.P., Wu J.Y., Chen R.K. Molecular cloning and expression analysis of a WRKY transcription factor in sugarcane. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2012;11:6434–6444. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang L., Liu F., Dai M.J., Sun T.T., Su W.H., Wang C.F., Zhang X., Mao H.Y., Su Y.C., Que Y.X. Cloning and expression characteristic analysis of ScWRKY4 gene in sugarcane. Acta Agron. Sin. 2018;44:1367–1379. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Que Y.X., Su Y.C., Guo J.L., Wu Q.B., Xu L.P. A global view of transcriptome dynamics during Sporisorium scitamineum challenge in sugarcane by RNAseq. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e106476. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chou K.C., Shen H.B. A new method for predicting the subcellular localization of eukaryotic proteins with both single and multiple sites: Euk-mPLoc 2.0. PLoS ONE. 2010;5:e9931. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0009931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishiguro S., Nakamura K. Characterization of a cDNA encoding a novel DNA-binding protein, SPF1, that recognizes SP8 sequences in the 5′ upstream regions of genes coding for sporamin and beta-amylase from sweet potato. Mol. Gen. Genet. 1994;244:563–571. doi: 10.1007/BF00282746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Eulgem T., Rushton P.J., Schmelzer E., Hahlbrock K., Somssich I.E. Early nuclear events in plant defence signalling: Rapid gene activation by WRKY transcription factors. Embo J. 1999;18:4689–4699. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.17.4689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu L.S., White M.J., Macrae T. Transcription factors and their genes in higher plants. FEBS J. 2010;262:247–257. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1999.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fan Z.Q., Tan X.L., Shan W., Kuang J.F., Lu W.J., Chen J.Y. BrWRKY65, a WRKY transcription factor, is involved in regulating three leaf senescence-associated genes in Chinese flowering cabbage. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2017;18:1228. doi: 10.3390/ijms18061228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wan Y.Q., Mao M.Z., Wan D.L., Yang Q., Yang F.Y., Mandlaa, Li G.J., Wang R.G. Identification of the WRKY gene family and functional analysis of two genes in Caragana intermedia. BMC Plant Biol. 2018;18:31. doi: 10.1186/s12870-018-1235-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lee H., Cha J., Choi C., Choi N., Ji H.S., Park S.R., Lee S., Hwang D.J. Rice WRKY11 plays a role in pathogen defense and drought tolerance. Rice. 2018;11:5. doi: 10.1186/s12284-018-0199-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang H.H., Meng J., Peng X.X., Tang X.K., Zhou P.L., Xiang J.H., Deng X.B. Rice WRKY4 acts as a transcriptional activator mediating defense responses toward Rhizoctonia solani, the causing agent of rice sheath blight. Plant Mol. Biol. 2015;89:157–171. doi: 10.1007/s11103-015-0360-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fields S., Song O. A novel genetic system to detect protein-protein interactions. Nature. 1989;340:245. doi: 10.1038/340245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sébastien B., Li J., Palva E.T. WRKY54 and WRKY70 co-operate as negative regulators of leaf senescence in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:2667–2679. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang X.T., Zeng J., Li Y., Rong X.L., Sun J.T., Sun T., Li M., Wang L.Z., Feng Y., Chai R.H., et al. Expression of TaWRKY44, a wheat WRKY gene, in transgenic tobacco confers multiple abiotic stress tolerances. Front. Plant Sci. 2015;6:615. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chi Y.C., Yang Y., Zhou Y., Zhou J., Fan B.F., Yu J.Q., Chen Z.X. Protein-protein interactions in the regulation of WRKY transcription factors. Mol. Plant. 2013;6:287–300. doi: 10.1093/mp/sst026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robatzek S., Somssich I.E. Targets of AtWRKY6 regulation during plant senescence and pathogen defense. Genes Dev. 2002;16:1139–1149. doi: 10.1101/gad.222702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Popescu S.C., Popeseu G.V., Bachan S., Zhang Z., Gerstein M., Snyder M., Dinesh-Kumar S.E. MAPK target networks in Arabidopsis thaliana revealed using functional protein microarrays. Genes Dev. 2009;23:80–92. doi: 10.1101/gad.1740009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhou L., Wang N.N., Kong L., Gong S.Y., Li Y., Li X.B. Molecular characterization of 26 cotton WRKY genes that are expressed differentially in tissues and are induced in seedlings under high salinity and osmotic stress. Plant Cell Tissue Org. Cult. 2014;119:141–156. doi: 10.1007/s11240-014-0520-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bakshi M., Oelmüller R. WRKY transcription factors: Jack of many trades in plants. Plant Signal. Behav. 2014;9:e27700. doi: 10.4161/psb.27700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bartels D., Sunkar R. Drought and salt tolerance in plants. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2005;24:23–58. doi: 10.1080/07352680590910410. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qiao Z., Li C.L., Zhang W. WRKY1 regulates stomatal movement in drought-stressed Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 2016;91:53–65. doi: 10.1007/s11103-016-0441-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Jiang Y.J., Yu D.Q. WRKY57 regulates JAZ genes transcriptionally to compromise Botrytis cinerea resistance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Physiol. 2016;171:2771–2782. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.00747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jones J.D., Dang J.L. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444:323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Métraux J.P., Nawrath C., Genoud T. Systemic acquired resistance. Euphytica. 2002;124:23–243. doi: 10.1023/A:1015690702313. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Katagiri F. A global view of defense gene expression regulation—A highly interconnected signaling network. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2004;7:506–511. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2004.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kunkel B.N., Brooks D.M. Cross talk between signaling pathways in pathogen defense. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2002;5:325–331. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chen X.T., Liu J., Lin G.F., Wang A., Wang Z.G., Lu G.D. Overexpression of AtWRKY28 and AtWRKY75 in Arabidopsis enhances resistance to oxalic acid and Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Plant Cell Rep. 2013;32:1589–1599. doi: 10.1007/s00299-013-1469-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wang H.H., Hao J.J., Chen X.J., Hao Z.N., Wang X., Lou Y.G., Peng Y.L., Guo Z.J. Overexpression of rice WRKY89 enhances ultraviolet B tolerance and disease resistance in rice plants. Plant Mol. Biol. 2007;65:799–815. doi: 10.1007/s11103-007-9244-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qiu D.Y., Xiao J., Ding X.H., Xiong M., Cai M., Cao Y.L., Li X.H., Xu C.G., Wang S.P. OsWRKY13 mediates rice disease resistance by regulating defense-related genes in salicylate- and jasmonate-dependent signaling. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2007;20:492–499. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-5-0492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Qiu D.Y., Xiao J., Xie W.B., Liu H.B., Li X.H., Xiong L.Z., Wang S.P. Rice gene network inferred from expression profiling of plants overexpressing OsWRKY13, a positive regulator of disease resistance. Mol. Plant. 2008;1:538–551. doi: 10.1093/mp/ssn012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zheng Z.Y., Mosher S.L., Fan B.F., Klessig D.F., Chen Z.X. Functional analysis of Arabidopsis WRKY25 transcription factor in plant defense against Pseudomonas syringae. BMC Plant Biol. 2007;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jiang Y., Deyholos M.K. Functional characterization of Arabidopsis NaCl-inducible WRKY25 and WRKY33 transcription factors in abiotic stresses. Plant Mol. Biol. 2009;69:91–105. doi: 10.1007/s11103-008-9408-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yokotani N., Sato Y., Tanabe S., Chujo T., Shimizu T., Okada K., Yamane K., Shimono M., Sugano S., Takatsuji H., et al. WRKY76 is a rice transcriptional repressor playing opposite roles in blast disease resistance and cold stress tolerance. J. Exp. Bot. 2013;64:5085–5097. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ert298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Liu X.F., Song Y.Z., Xing F.Y., Wang N., Wen F.J. GhWRKY25, a group I WRKY gene from cotton, confers differential tolerance to abiotic and biotic stresses in transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana. Protoplasma. 2015;253:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s00709-015-0885-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang X., Yan Y., Li Y.Z., Chu X.Q., Wu C.G., Guo X.Q. GhWRKY40, a multiple stress-responsive cotton WRKY gene, plays an important role in the wounding response and enhances susceptibility to Ralstonia solanacearum infection in transgenic Nicotiana benthamiana. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e93577. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Mukhtar M.S., Deslandes L., Auriac M., Marco Y., Somssich I.E. The Arabidopsis transcription factor WRKY27 influences wilt disease symptom development caused by Ralstonia solanacearum. Plant J. 2008;56:935. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03651.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Su Y.C., Guo J.L., Ling H., Chen S.S., Wang S.S., Xu L.P., Allan A.C., Que Y.X. Isolation of a novel peroxisomal catalase gene from sugarcane, which is responsive to biotic and abiotic stresses. PLoS ONE. 2014;9:e84426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0084426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li H., Gao Y., Xu H., Dai Y., Deng D.Q., Chen J.M. ZmWRKY33, a WRKY maize transcription factor conferring enhanced salt stress tolerances in Arabidopsis. Plant Growth Regul. 2013;70:207–216. doi: 10.1007/s10725-013-9792-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Scarpeci T.E., Zanor M.I., Zanor M.I., Mueller-Roeber B., Valle E.M. Overexpression of AtWRKY30 enhances abiotic stress tolerance during early growth stages in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Mol. Biol. 2013;83:265–277. doi: 10.1007/s11103-013-0090-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Marchlerbauer A., Bo Y., Han L.Y., He J., Lanczycki C.J., Lu S.N., Chitsaz F., Derbyshire M.K., Geer R.C., Gonzales N.R., et al. CDD/SPARCLE: Functional classification of proteins via subfamily domain architectures. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:200–203. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gasteiger E., Hoogland C., Gattiker A., Duvaud S., Wilkins M.R., Appel R.D., Bairoch A. The Proteomics Protocols Handbook. Humana Press; New York, NY, USA: 2005. Protein identification and analysis tools on the ExPASy server; pp. 571–607. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Combet C., Blanchet C., Geourjon C., Deléage G. NPS@: Network protein sequence analysis. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2000;25:147–150. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(99)01540-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Petersen T.N., Brunak S., Heijne G., Nielsen H. SignalP 4.0: Discriminating signal peptides from transmembrane regions. Nat. Methods. 2011;8:785–786. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Nielsen H. Predicting secretory proteins with SignalP. Methods Mol. Biol. 2017;1611:59–73. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-7015-5_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Krogh A., Larsson B., Heijne G.V., Sonnhammer E.L.L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden markov model: Application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001;305:567–580. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2000.4315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kumar S., Stecher G., Tamura K. MEGA7: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33:1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Wang C., Deng P., Chen L., Wang X., Ma H., Hu W., Yao N.C., Feng Y., Chai R.H., Yang G.X., et al. A wheat WRKY transcription factor TaWRKY10 confers tolerance to multiple abiotic stresses in transgenic tobacco. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e65120. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Curtis M.D., Grossniklaus U. A gateway cloning vector set for high-throughput functional analysis of genes in planta. Plant Phyosiol. 2003;133:462–469. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.027979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hwang I.S., Hwang B.K. Requirement of the cytosolic interaction between pathogenesis-related protein10 and leucine-rich repeat protein1 for cell death and defense signaling in pepper. Plant Cell. 2012;24:1675–1690. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.095869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Fan Z.Q., Kuang J.F., Fu C.C., Shan W., Han Y.C., Xiao Y.Y., Ye Y.J., Lu W.J., Lakshmanan P., Duan X.W., et al. The banana transcriptional repressor MaDEAR1 negatively regulates cell wall-modifying genes involved in fruit ripening. Front. Plant Sci. 2016;7:1021. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2016.01021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Shen C.J., Wang S.K., Bai Y.H., Wu Y.R., Zhang S.N., Chen M., Guilfoyle T.J., Wu P., Qi Y.H. Functional analysis of the structural domain of ARF proteins in rice (Oryza sativa L.) J. Exp. Bot. 2010;61:3971–3981. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Schütze K., Harter K., Chaban C. Bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC) to study protein-protein interactions in living plant cells. Methods Mol. Biol. 2009;479:189–202. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-289-2_12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mersereau M., Pazour G.J., Das A. Efficient transformation of Agrobacterium tumefaciens by electroporation. Gene. 1990;90:149–151. doi: 10.1016/0378-1119(90)90452-W. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Livak K.J., Schmittgen T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−∆∆CT method. Methods. 2001;25:402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Su Y.C., Wang Z.Q., Li Z., Xu L.P., Que Y.X., Dai M.J., Chen Y.H. Molecular cloning and functional identification of peroxidase gene ScPOD02 in sugarcane. Acta Agron. Sin. 2017;43:510–521. doi: 10.3724/SP.J.1006.2017.00510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Earley K.W., Haag J.R., Pontes O., Opper K., Juehne S., Song K., Pikaard C.S. Gateway-compatible vectors for plant functional genomics and proteomics. Plant J. 2006;45:616–629. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2005.02617.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Peng Q., Su Y.C., Ling H., Ahmad W., Gao S.W., Guo J.L., Que Y.X., Xu L.P. A sugarcane pathogenesis-related protein, ScPR10, plays a positive role in defense responses under Sporisorium scitamineum, SrMV, SA, and MeJA stresses. Plant Cell Rep. 2017;36:1427–1440. doi: 10.1007/s00299-017-2166-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Lai Y., Dang F.F., Lin J., Yu L., Shi Y.L., Xiao Y.H., Huang M.K., Lin J.H., Chen C.C., Qi A.H. Overexpression of a Chinese cabbage BrERF11, transcription factor enhances disease resistance to Ralstonia solanacearum, in tobacco. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2013;62:70–78. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2012.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data