Abstract

Background

Standardization of the intravenous glucose tolerance test (ivGTT) in cattle has received little attention despite its widespread use to monitor glucose metabolism. The impact of management practices including several sensorial stimuli on test responses has not yet been described in young cattle. The objective of this study was to analyze the effects of noise exposure, and visual food stimuli in combination with physical restraint on ivGTT and insulin traits in Holstein cattle. A total of 108 ivGTT (6 tests per animal) were performed in bulls (n = 6), steers (n = 6), and heifers (n = 6) aged 312 to 344 days. The main parameters analyzed for glucose and insulin included: basal concentration (G0, Ins0), maximum concentration (GMAX, InsMAX), and final concentration at 63 min (G63, Ins63), glucose and insulin area under the curve (GAUC, InsAUC), and glucose half-life time (GHLT). Noise stimuli were induced by playing rock music at approximately 90 dB either before (NI) or immediately after glucose injection (NII). Visual food stimuli were induced by feeding the neighboring animals while the tested animal was restrained in a headlock.

Results

Almost all glucose and insulin traits were affected by gender (P< 0.05) whereas the factor with least impact on ivGTT was NI. InsMAX and InsAUC were affected (P < 0.002) by all factors analyzed. GHLT and G63 were affected by gender and noise with higher values in bulls when compared to steers and heifers. Furthermore, InsAUC and InsMAX values derived from NII significantly differed in bulls when compared to steers and heifers. Significantly higher values for G0 (P < 0.001), InsMAX (P < 0.001) and InsAUC (P = 0.001) were observed when exposed to the visual food stimulus whereas GMAX (P = 0.02) and GAUC (P = 0.04) decreased. Higher Ins63 values were observed in bulls exposed to the visual food stimulus when compared to heifers.

Conclusions

Short-term exposure to noise and visual food stimuli might lead to variations in glucose metabolism and insulin secretion which emphasizes the necessity to avoid practices involving auditory or visual stimuli prior to or during the conduction of an ivGTT.

Keywords: Cattle, Glucose tolerance test, Insulin, Noise

Background

Frequent monitoring of management practices is essential to identify factors generating stress in dairy and beef cattle farms [1]. Sounds, commonly defined as noise, might trigger stress responses attributed to painful stimuli or altered behavior affecting several organs [2]. For instance, the level of noise in livestock production, measured in the frequencies from 25 to 35 kHz (i.e. audible range for cattle [3]) has been associated not only with increased respiratory and heart rate [4] but also with altered production traits [5]. Therefore, avoiding noise-derived stressful situations seem to lead to better welfare [6]. Nevertheless, there is little evidence about the reference values of unwanted sounds for most management systems although it is known that cattle are able to respond with changes in the neuroendocrine system when stressors are intermittent [7]. Additionally, evidence suggests that carbohydrate metabolism is affected in ruminants exposed to a range of noises produced by an industrial engine or human vocalizations [2]. However, alterations in glucose tolerance and insulin concentrations as a result of noise exposure in dairy or beef cattle have not yet been reported.

One of the most common methods to study glucose metabolism in cattle includes the calculation of glucose removal rates from the blood stream under the influence of insulin commonly performed using an intravenous glucose tolerance test (ivGTT) [8, 9]. Changes on glucose concentration at specific time points post glucose infusion reflect the ability of an organism to rapidly utilize the metabolite which comprises the individual glucose and insulin reaction [10]. The information obtained from these responses is routinely used to assess conditions such as insulin resistance [11], diagnose diabetes, although its incidence in cattle is very low [12], determine the impact of certain compounds on insulin sensitivity [13] among other applications. Despite the wide implementation of ivGTT in cattle, careful data interpretation is always recommended because test standardization is lacking [14]. Recently, the effects of food deprivation times [14] and glucose dose [15] on ivGTT and insulin traits have been demonstrated. Similarly, the consequences of some management practices involving auditory and visual stimuli taking place during conduction of ivGTT might alter the ability of the different organs to use and dispose glucose and insulin; however, reports on this field are unavailable in cattle. Current animal housing facilities are surrounded by a wide range of auditory stimuli derived mostly from human activities which represent not only a potential source of animal discomfort but also a confounding factor when assessing glucose and insulin concentrations [16]. Thus, we aimed to determine the influence of short-term auditory and visual food stimuli on glucose metabolism and insulin concentration in young Holstein cattle.

Methods

Animals

Eighteen animals were purchased from a commercial dairy farm located in Brandenburg, Germany. Holstein bulls (n = 6), steers (n = 6), and heifers (n = 6) were included in the study. Castration was performed 10 wk prior to study conduction. Experiments took place after a period of 8 wk used for acclimation to the new diet, housing, and personnel. At the beginning of the study, bulls, steers, and heifers were 318 (SD = 16.3), 312 (SD = 46.3), and 344 days (SD = 16.2) old, respectively. Body weights (BW) were different among groups: bulls, steers, and heifers had BW of 364 (SD = 21.8), 335 (SD = 22.1), and 347 kg (SD = 32.2), respectively. Animals were housed in individual stalls with headlocks on straw bedding in experimental facilities at the Ruminant and Swine Clinic, Free University of Berlin, Germany.

Study design

Animals were enrolled during two seasons: (1) May to November and (2) December to May of the following year. Different individuals were used during the two periods. Each individual was tested 6 times namely on day 1, 8, 10, 15, 22, and 36. A total of 108 ivGTT were carried out. Tests 1, 4 and 6 served as controls. Results from these tests derived from undisturbed animals (no auditory or visual stimuli were implemented). During tests 2 and 3, noises were induced and for test 5 a visual food stimulus was applied.

Diet

Animals were fed a diet containing 1 kg hay and 1.5 kg concentrate offered four times a day, and straw ad libitum. Feed analysis and ration composition are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Feed analyses and ration composition of experimental diet

| Hay | Pellet concentrate | Wheat straw | Calculated ration composition | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DM in OM (%) | 86 | 89 | 87 | 88 |

| Ash (g/kg) in DM | 109 | 61 | 81 | 80 |

| Metabolizable energy (MJ/kg) in DM | 9.4 | 12.1 | 6.2 | 10.9 |

| Crude protein (g/kg) in DM | 138 | 140 | 32 | 135 |

| Crude fiber (g/kg) in DM | 293 | 80 | 489 | 176 |

| Crude fat (g/kg) in DM | 32 | 36 | 12 | 34 |

| Starch (g/kg) in DM | 0 | 260 | 11 | 152 |

| Sugar (g/kg) in DM | ND | 82 | ND | 48 |

| Calcium (g/kg) in DM | 9.4 | 6.1 | 3.1 | 8.3 |

| Phosphorus (g/kg) in DM | 3.1 | 2.9 | 0.8 | 3.3 |

| Sodium (g/kg) in DM | 0.8 | 2.4 | 1.3 | 1.7 |

| Magnesium (g/kg) in DM | 1.9 | 2.3 | 1.0 | 2.1 |

| kg OM a | 1a | 1.5a | 0.1a | – |

DM dry matter, OM organic matter, ND not determined

aRation given 4 times/day

Acoustic exposure

To determine the influence of noise on glucose tolerance, animals were exposed to loud rock music, noises provoked by beating a metal bar against a metal shovel combined by human vocalizations close to the animal’s head at approximately 90 dB. At test number 2, the noise was induced immediately prior to conduction of ivGTT (glucose injection) and was defined as noise I (NI). The same noise exposure was repeated at the following examination (test number 3) but it was initiated once glucose injection was completed and ended before the second blood collection at min 7. This experiment was defined as noise II (NII). Both noise exposures lasted for 5 min.

Visual food stimuli

At test number 5, animals were subjected to visual food stimuli under physical restraint by fixing the head in the headlock and feeding behavior from neighboring animals prior to the test. Glucose infusion started immediately after visual stimuli. For that, fed animals were located directly next to the food-restricted group on both sides of the stall. Grain (1.5 kg) was offered to fed animals and ivGTT was conducted only on food-restricted animals. This experiment examined the influence of short-term food restriction and visual food stimulus on glucose tolerance test traits. Each visual exposure stimulus lasted until the non-deprived animals finished their ration (~ 5–10 min). Animal test allocation was reversed on the following day. Animals fed on the previous day were now food-restricted and subjected to ivGTT.

Glucose tolerance test

Animals were fasted for 12 h prior to ivGTT with water available at all the times. On testing days, they were only loosely fixed on the neck using a head halter attached to headlocks. Subsequently, an indwelling 14 G × 8 cc cannula (Melsungen AG, Melsungen, Germany) was inserted in the jugular vein and fixed to the skin to minimize the effects of handling on glucose metabolism. Animals were accustomed to the personal and very often lying behavior during blood collection was observed. The ivGTT was conducted as described previously [17]. Briefly, the first blood sample was obtained immediately prior to glucose i.v. administration using a 40% solution (B Braun Vet Care, Melsungen AG, Melsungen, Germany) at 1 g/kg BW0.75. Glucose administration lasted for 0.5 to 1 min followed by catheter flushing with 0.9% NaCl solution (Isotone Kochsalz-Lösung, B Braun Melsungen AG, Melsungen, Germany). The blood samples were drawn every 7 min until min 63 for a total of 10 individual samples. Serum was recovered and stored at − 18 °C until analyzed.

Serum glucose concentration was estimated by the hexokinase method using the Gluco-quant Glucose/HK Cobas® test (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions using an automatic spectrophotometer analyzer (Cobas Mira Plus CC®, Roche Diagnostic GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). Minimal detectable concentration for this method was 0.11 mmol/L and intra-and inter-assay coefficient of variation were 1.8 and 4.4%, respectively. Insulin concentration was assessed by solid phase radioimmunoassay using a commercial kit (Radioimmuno-coat-A-count insulin®, DPC Bierman GmbH, Germany) as described by Kremer [18]. Analytical sensitivity was 1.2 µIU/mL and intra-and inter-assay coefficient of variation were 5.0 to 6.3% and 5.6 to 12.4%, respectively.

Parameters analyzed for ivGTT included: basal glucose (G0) and insulin concentration (Ins0), maximum glucose (GMAX) and insulin concentration (InsMAX), glucose (G63) and insulin (Ins63) concentration at the end of the test, glucose half-life time (GHLT), and area under the curve for glucose (GAUC) and insulin (InsAUC). GHLT was calculated as described by Kaneko et al. [8] using linear regression analysis of the natural logarithm of the glucose concentrations as follows:

The letter (k) represents a coefficient determined by the following formula:

From the previous formula, letters G and T represent glucose concentrations and time points in minutes post glucose infusion, respectively. Numbers 14 and 42 denote min post glucose injection. Area under the curve was estimated using the trapezoidal rule.

Statistical analyses

Glucose and insulin traits derived from each examination were analyzed for normal distribution using graphical methods and Shapiro–Wilk test. All glucose and two insulin traits (InsMAX, InsAUC) were normally distributed, whereas base-10 logarithmic transformation was applied to Ins0 and Ins63. Results were back-transformed for graphical representation. Descriptive statistics included median, percentiles 25 and 75, maximum and minimum values (Table 2). Total number of observations was 108 for three glucose and two insulin traits, whereas 1–3 observations were removed from the calculations for each of the remaining glucose and insulin variables due to extreme deviations (more than 2.5 ± SD compared to the group mean). Sample size is shown in Tables 3 and 4. Generalized linear mixed models were implemented to determine the influence of gender, noise, and visual food stimulus on glucose and insulin. Interactions between food stimulus and noise with gender were tested in the model and significant interactions were presented (Figs. 1, 2, 3). Animal was included as a random effect in all models to account for repeated measurements in the same tested animals. Residuals were analyzed for outliers, homoscedasticity, and normal distribution. Statistical analyses were carried out with SPSS® version 22 (IBM Deutschland GmbH, Ehningen). Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for intravenous glucose tolerance test and insulin traits

| Variable | n | Median | Percentile 25 | Percentile 75 | Minimum | Maximum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G0 (mmol/L) | 108 | 4.99 | 4.76 | 5.37 | 3.90 | 5.84 |

| GMAX (mmol/L) | 108 | 13.8 | 13.3 | 14.4 | 12.1 | 16.1 |

| G63 (mmol/L) | 108 | 6.26 | 5.56 | 6.99 | 3.52 | 8.06 |

| GHLT (min) | 108 | 46.7 | 40.4 | 54.4 | 26.6 | 67.3 |

| GAUC (mmol/L/63 min) | 108 | 204.6 | 178.9 | 226.5 | 129.7 | 269.7 |

| Ins0 (μIU/mL) | 108 | 8.82 | 6.79 | 11.5 | 4.39 | 28.9 |

| InsMAX (μIU/mL) | 108 | 128.4 | 93.0 | 176.4 | 51.7 | 326.2 |

| Ins63 (μIU/mL) | 108 | 22.5 | 15.1 | 33.5 | 6.5 | 102.1 |

| InsAUC (μIU/mL/63 min) | 108 | 3977.0 | 2983.7 | 5213.4 | 1741.2 | 9968.1 |

G0 basal glucose concentration, GMAX maximum increase in glucose concentration, G63 glucose concentration at min 63, GHLT glucose half-life time, GAUC glucose area under the curve, Ins0 basal insulin concentration prior to glucose injection, InsMax maximum increase in blood insulin concentration, Ins63 insulin concentration at min 63, InsAUC insulin area under the curve

Table 3.

Generalized linear mixed-models for gender, and management factors on i.v. glucose tolerance test traits

| Fixed effects | G0a mmol/L | GMAX mmol/L | G63 mmol/L | GHLTb min | GAUC mmol/L/63 min | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ß | SE | P | ß | SE | P | ß | SE | P | ß | SE | P | ß | SE | P | |

| Intercept | 4.70 | 0.08 | < 0.001 | 14.2 | 0.15 | < 0.001 | 5.97 | 0.22 | < 0.001 | 44.02 | 1.56 | < 0.001 | 204.27 | 4.09 | < 0.001 |

| Gender | < 0.001 | 0.03 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ns | ||||||||||

| Bull | 0.57 | 0.11 | < 0.001 | − 0.52 | 0.21 | 0.01 | 0.64 | 0.31 | 0.04 | 10.17 | 2.23 | < 0.001 | – | – | – |

| Steer | 0.21 | 0.11 | 0.05 | − 0.40 | 0.21 | 0.05 | 0.30 | 0.31 | 0.34 | 3.30 | 2.21 | 0.13 | – | – | – |

| Heifer | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Noise (N) | ns | ns | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | ns | ||||||||||

| I | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.12 | 0.28 | 0.66 | − 3.51 | 2.50 | 0.16 | – | – | – |

| II | – | – | – | – | – | – | − 0.89 | 0.26 | 0.001 | − 7.49 | 2.23 | 0.001 | – | – | – |

| Undisturbed | – | – | – | – | – | – | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | – | – | – |

| Food stimuli (FS) | < 0.001 | 0.02 | ns | ns | 0.04 | ||||||||||

| Food-stimulated | 0.19 | 0.05 | < 0.001 | − 0.36 | 0.16 | 0.02 | – | – | – | – | – | – | − 14.12 | 7.09 | 0.04 |

| Undisturbed | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | – | – | – | – | – | – | ref | ref | ref |

| Gender*N | ns | ns | 0.001 | < 0.001 | ns | ||||||||||

| [Bull]*[N I] | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.40 | 0.40 | 0.31 | 5.87 | 3.55 | 0.10 | – | – | – |

| [Bull]*[N II] | – | – | – | – | – | – | 1.31 | 0.37 | 0.001 | 10.79 | 3.18 | 0.001 | – | – | – |

| [Bull]*[undisturbed] | – | – | – | – | – | – | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | – | – | – |

| [Steer]*[N I] | – | – | – | – | – | – | − 0.07 | 0.40 | 0.86 | − 0.09 | 3.54 | 0.98 | – | – | – |

| [Steer]*[N II] | – | – | – | – | – | – | − 0.29 | 0.37 | 0.43 | − 4.15 | 3.16 | 0.19 | – | – | – |

| [Steer]*[undisturbed] | – | – | – | – | – | – | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | |||

ß coefficient, G0 basal glucose concentration prior to injection, GMAX maximum increase in blood glucose concentration, G63 glucose concentrations at min 63, GHLT glucose half-life time, GAUC glucose area under the curve, N noise, FS food stimuli, ns no statistically significant difference, – not shown because values were not statistical significant, ref referent category

aG0 was estimated based on n = 105

bGHLTwas estimated based on n = 107

Table 4.

Generalized linear mixed-model for gender, and management factors on insulin traits

| Fixed effects | Ins0 µIU/mL | InsMAXa µIU/mL | Ins63 µIU/mL | InsAUCb µIU/ml/63 min | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ß | SE | P | ß | SE | P | ß | SE | P | ß | SE | P | |

| Intercept | 0.34 | 0.03 | < 0.001 | 105.85 | 12.57 | < 0.001 | 1.31 | 0.07 | < 0.001 | 3313.4 | 353.6 | < 0.001 |

| Gender | ns | < 0.001 | 0.03 | 0.002 | ||||||||

| Bull | – | – | – | − 1.05 | 17.23 | 0.95 | 0.09 | 0.10 | 0.36 | 225.4 | 487.7 | 0.64 |

| Steer | – | – | – | 30.01 | 17.23 | 0.08 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.68 | 731.3 | 487.7 | 0.13 |

| Heifer | – | – | – | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Noise (N) | ns | < 0.001 | ns | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| I | – | – | – | 47.13 | 20.80 | 0.02 | – | – | – | 851.5 | 622.9 | 0.17 |

| II | – | – | – | 81.71 | 18.30 | < 0.001 | – | – | – | 2126.6 | 441.5 | < 0.001 |

| Undisturbed | – | – | – | ref | ref | ref | – | – | – | ref | ref | ref |

| Food stimuli (FS) | ns | < 0.001 | 0.02 | 0.001 | ||||||||

| Food-stimulated | – | – | – | 50.49 | 11.43 | < 0.001 | − 0.25 | 0.06 | < 0.001 | 993.9 | 281.1 | 0.001 |

| Undisturbed | – | – | – | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref | ref |

| Gender*N | ns | 0.001 | ns | < 0.001 | ||||||||

| [Bull]*[N I] | – | – | – | − 53.87 | 29.10 | 0.06 | – | – | – | − 1290.1 | 839.1 | 0.12 |

| [Bull]*[N II] | – | – | – | − 67.29 | 24.57 | 0.007 | – | – | – | − 2047.3 | 591.3 | 0.001 |

| [Bull]*[Undisturbed] | – | – | – | ref | ref | ref | – | – | – | ref | ref | ref |

| [Steer]*[N I] | – | – | – | − 9.63 | 29.10 | 0.74 | – | – | – | − 7.16 | 839,1 | 0.99 |

| [Steer]*[N II] | – | – | – | 34.36 | 24.57 | 0.16 | – | – | – | 594.4 | 591.3 | 0.31 |

| [Steer]*[Undisturbed] | – | – | – | ref | ref | ref | – | – | – | ref | ref | ref |

| Gender*FS | ns | ns | < 0.001 | ns | ||||||||

| [Bull]*[Food-restricted] | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.35 | 0.08 | < 0.001 | – | – | – |

| [Bull]*[Undisturbed] | – | – | – | – | – | – | ref | ref | ref | – | – | – |

| [Steer]*[Food-restricted] | – | – | – | – | – | – | 0.19 | 0.08 | 0.02 | – | – | – |

| [Steer]*[Undisturbed] | – | – | – | – | – | – | ref | ref | ref | – | – | – |

Values from Ins0 and Ins63 derived from base-10 logarithmic transformations

ref reference values, ß coefficient, Ins0 basal insulin concentration prior to glucose injection, InsMAX maximum increase in blood insulin concentration, Ins63 insulin concentrations at 63 min, InsAUC insulin area under the curve, N noise, FS food stimuli, ns no statistically significant difference, – not shown because values were not statistically significant, ref referent category

aInsMax was estimated based on n = 107

bInsAUC was estimated based on n = 106

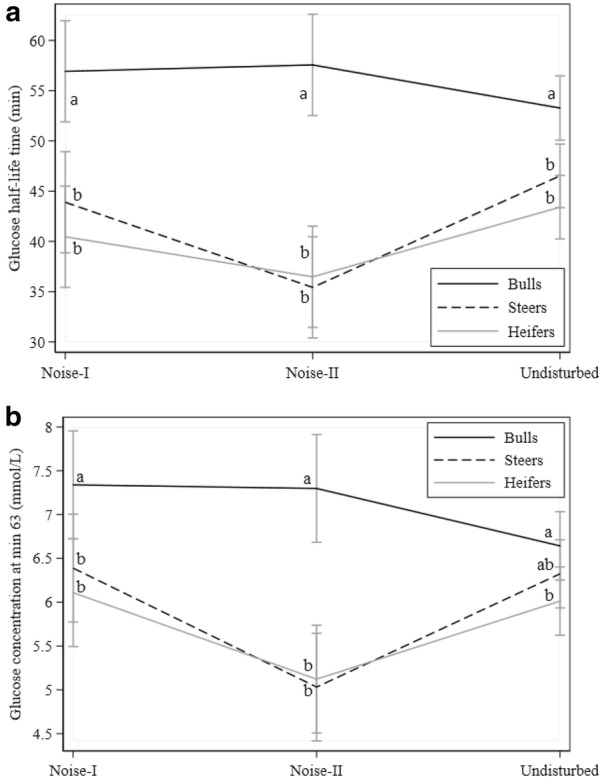

Fig. 1.

Effects of noise on glucose traits: a glucose half-life time, and b glucose concentration at min 63. Black, dotted, and gray lines denote bulls, steers, and heifers, respectively. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between groups

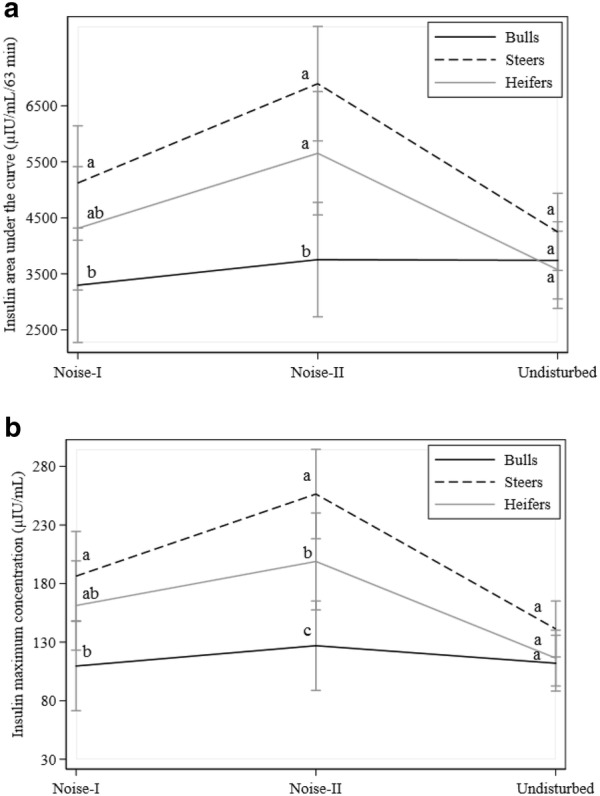

Fig. 2.

Effects of noise on insulin traits: a insulin area under the curve, and b insulin maximum concentration. Black, dotted, and gray lines denote bulls, steers, and heifers, respectively. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between groups

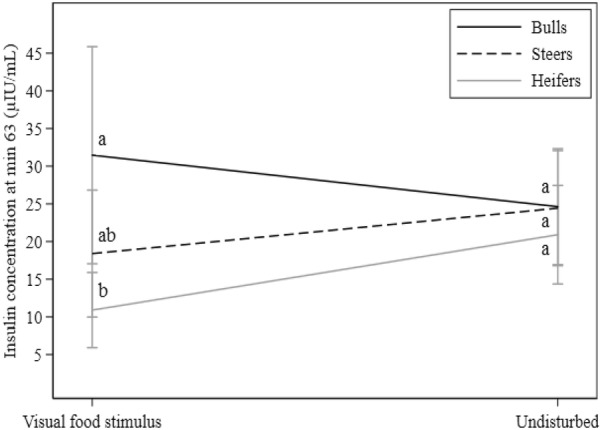

Fig. 3.

Effects of deprivation food on insulin concentration at min 63. Black, dotted, and gray lines denote bulls, steers, and heifers, respectively. Different letters indicate statistically significant differences between groups. Values were back-transformed from the log scale for representation

Results

Descriptive statistics

Descriptive statistics for glucose and insulin are displayed in Table 2. On average, G0 was 4.99 mmol/L [inter quartile range (ICR) 4.76–5.37] and increased 8.8 mmol/L to a GMAX of 13.8 mmol/L (ICR 13.3–14.4). At min 63, glucose concentration was 6.26 mmol/L (ICR 5.56–6.99) and GHLT 46.7 min (ICR 40.4–54.4). Variability in insulin values was much greater in all measurements. The median Ins0 was at 8.82 μIU/mL (ICR 6.79–11.5) and increased by 119.6 μIU/mL to an InsMax of 128.4 (ICR 93.0–176.4 μIU/mL). At the last measurement, Ins63 decreased to 22.5 μIU/mL (ICR 15.1–33.5).

Gender

Gender had an influence on most of the parameters assessed (except Ins0 and GAUC; Tables 3 and 4). Due to the interaction effects, coefficients for this independent variable cannot be interpreted without taking these interactions into account. Nevertheless, values for steers were often between those of heifers and bulls but not significantly different from heifers (Tables 3 and 4). On the other hand, bulls had significantly different values from those of heifers for most parameters.

Noise

Noise had an effect on GHLT, G63, InsAUC, and InsMAX (P < 0.05, Tables 3 and 4) and interaction of noise with gender was present for these traits (Figs. 1 and 2). Compared to undisturbed animals, GHLT values from heifers and steers decreased with NII exposure while values from bulls increased (Fig. 1a). Similarly, G63 values decreased in heifers and steers with NII and increased in bulls (Fig. 1b). However, highest values for G63 in bulls were observed when exposed to NI. For InsAUC and InsMAX (Fig. 2a, b), values for heifers and steers increased with NII and returned to close to undisturbed values for NI exposure. On the other hand, values in bulls almost remained unchanged for InsAUC and InsMAX.

Visual food stimulus

Visual food stimuli and feeding behavior from neighboring animals influenced most glucose and insulin traits in tested animals (Tables 3 and 4, Fig. 3). Food-stimulated animals showed increased values for G0 (0.19 mmol/L, P < 0.001), InsMAX (50.5 μIU/mL, P < 0.001), and InsAUC (993.9 μIU/mL/63 min, P = 0.001) when compared to control animals (undisturbed). Significant differences were also found between food-stimulated and control animals for GMAX (− 0.36 mmol/L, P = 0.02) and GAUC (− 14.12 mmol/L/63 min, P = 0.04) with decreasing values in the former group. Ins63 increased when exposed to the visual food stimulus in bulls but decreased in heifers (Table 4, Fig. 3) when compared to control animals; however, no effect was observed in steers. The food stimulus did not affect G63, GHLT, and Ins0.

Discussion

The impact of unwanted sounds commonly defined as “noises” on health has received considerable attention in animal and human studies [19, 20]. However, studies focusing on the effects of noise on glucose tolerance during short-time exposure in cattle are limited. Consequently, it is imperative to determine if noises derived from animal husbandries or humans could alter the responses obtained from an ivGTT. In humans, it has been shown that noise exposure (45 dB) during four consecutive nights altered glucose metabolism in healthy participants under controlled conditions [21]. This study reported significantly decreased basal glucose concentrations and elevated glucose and insulin area under the curve in the exposed group. Engine noises around 97 dB were associated with increased blood glucose concentrations and leucocyte counts in dairy cows [2]. However, neither glucose elimination nor insulin secretion rates were reported. Furthermore, rodents exposed to long-term noises developed insulin resistance and increased stress hormones concentrations [22]. The investigators introduced noises at 95 dB to male mice during 4 h for 1 day and reported decreased glucose tolerance characterized by significantly higher GMAX and GAUC when compared to the control group. Daily noise exposure for 10 or 20 days resulted in significantly higher insulin (InsMAX, InsAUC). Interestingly, these last traits were also affected in our experiments despite the animals were only exposed for 5 min prior to ivGTT (NI) or during the first 5 min after glucose injection (NII). ivGTT traits from animals exposed to NI showed no differences when compared to undisturbed animals but findings derived from NII evidenced significantly lower G63, GHLT, and higher insulin values (e.g. InsMAX, InsAUC) resulting in increased glucose tolerance. The differences in G63, GHLT were only observed in heifers and steers which might be explained by their increased sensitivity to sudden environmental stimuli (sound and motion) as reported by Lanier et al. [23]. Other experiments have found gender differences on behavior and cortisol levels in testosterone propionate-treated heifers exposed to fear [21]. For instance, an association between steroid administration and fearfulness reduction to novel objects or unfamiliar surroundings due to the inhibitory functions of testosterone on adrenal function has been documented [24]. Thus, differences in GHLT and G63 traits in animals exposed to noise might be attributed to steroid concentrations with statistically significant higher values in bulls when compared to steers and heifers. One limitation of the present study is that stress hormones during and after the ivGTT were not assessed. Consequently, underlying the mechanisms that could explain differences in glucose and insulin traits due to alterations on the hypothalamus–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPAA) remain elusive. However, evidence showed that steers at 15–16 months old had statistically significant elevated cortisol concentrations prior to truck loading when compared to bulls [25]. This difference might be attributed to impaired feedback at the HPAA in castrated animals [26, 27] affecting glucose tolerance and insulin concentration as observed in our study. Nevertheless, strong relationships between serum glucose and cortisol concentrations have been reported [28].

Cephalic phase insulin release (CPIR, i.e. the insulin secretion by the pancreas during the cephalic phase of digestion) occurs prior to or during food ingestion and it is caused by neuro-mediated sensory stimuli such as sight, smell or taste [29, 30]. Visual food stimuli experiments conducted in monogastric species reported rapid elevation in basal insulin concentration due to increased epinephrine release [31]. In lactating cows, food presentation for few min prior to its consumption resulted in significant increases in glucose and insulin concentrations [32] whereas other reports have only found similar responses within 2–10 min after feeding in cows [33] and steers [34]. Interestingly, ewes which underwent vagotomy showed a significant increase in plasma insulin concentrations 2 min after the presentation of food with elevated values for 6 min [35]. Similarly, in our study almost all ivGTT traits for glucose and insulin were affected by the visual food stimulus except for G63, GHLT, and Ins0. Therefore, CPIR might account for the elevated insulin concentrations in InsAUC and InsMAX found in this study. However, because assessments of insulin concentration during the first min after food exposure were not performed, we can only speculate a primary role of food-related sensory stimuli on rapid insulin release. On the other hand, one limitation of the current study is that the visual food stimulus was also accompanied by physical restraint which could cause anxiety in the experimental animals with subsequent activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis. This experiment was intended to combine both stimuli (physical restraint and visual food stimulus) because during the conduction of an ivGTT, animal fixation is commonly used to obtain periodic blood samples. Despite the CPIR has been reported in ruminants [35], physical restraint and individual frustration due to inability to access food might also explain our findings. A combination of factors including early insulin and stress-induced epinephrine secretion, and steroidal hormone concentration might clarify the responses observed in glucose tolerance. A study conducted by Lewis [36] found increased general activity, frustration behavior and significantly elevated cortisol concentrations in Cotswold pigs when they were unable to access food stored in lidded feeders. Thus, it is possible that food presentation stimulated neural control of insulin secretion as observed in other species [29]. Our results evidenced the importance of avoiding feeding practices and auditory stimuli around the time of ivGTT implementation to minimize confounding factors. Standardized test conditions and calm handling have to be ensured to obtain reliable data. Furthermore, there were significant gender differences regarding the reaction to the stimuli applied in this study. Steers were metabolically more similar to heifers than to bulls. This indicates that heifers and steers might be more prone to stressful disturbances involving noises whereas bulls might be more sensitive to frustrating situations, such as observing fed stall mates.

Conclusions

Glucose tolerance test and insulin traits were highly affected by noises and visual food stimuli. These effects have to be considered and avoided when conducting the test for research or diagnostic purposes.

Authors’ contributions

LAGG analyzed and interpreted the data and wrote the manuscript. LP contributed substantially to finalize the manuscript and to the statistical analysis. PG and SG aided in designing the study and obtaining and processing the data. RS conceived and planned the study and collaborated in the interpretation of the results. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Ms. Michaela Waberowski for assisting hormone assays analyses.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Experimental procedures used in this study were approved and supervised by the Landesamt für Arbeitsschutz, Gesundheitsschutz und technische Sicherheit in Berlin, Germany (Protocol Number G 0023/04).

Funding

This study was partially funded by Technologie und Produktentwicklung Dr. Pieper GmbH (Wuthenow, Germany).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- G0

basal glucose concentration

- Ins0

basal insulin concentration

- BW

body weight

- CPIR

cephalic phase insulin release

- FS

food stimuli

- GAUC

glucose area under the curve

- G63

glucose concentration at min 63

- GHLT

glucose half-life time

- HPAA

hypothalamus pituitary adrenal axis

- InsAUC

insulin area under the curve

- Ins63

insulin concentration at min 63

- ICR

inter quartile range

- ivGTT

intravenous glucose tolerance test

- GMAX

maximum glucose concentration

- InsMAX

maximum insulin concentration

- NII

noise stimulus after glucose infusion

- NI

noise stimulus prior to glucose infusion

Contributor Information

Leslie Antonio González-Grajales, Email: leslieantonio.gonzalezgrajales@fu-berlin.de.

Laura Pieper, Email: laura.pieper@fu-berlin.de.

Philipp Görner, Email: philippgoerner@web.de.

Stefan Görner, Email: stefangoerner@gmx.de.

Rudolf Staufenbiel, Email: rudolf.staufenbiel@fu-berlin.de.

References

- 1.Lyles JL, Calvo-Lorenzo MS, Bill E. Kunkle Interdisciplinary Beef Symposium practical developments in managing animal welfare in beef cattle what does the future hold? J Anim Sci. 2014;92:5334–5344. doi: 10.2527/jas.2014-8149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brouček J. Effect of noise on performance, stress and behaviour of animals. Slovak J Anim Sci. 2014;47:111–123. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Heffner HE, Heffner RS. Auditory perception. In: Phillips CJC, Piggins D, editors. Farm animals and the environment. Wallingford: CAB International; 1993. pp. 159–184. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waynert DF, Stookey JM, Schwartzkopf-Genswein KS, Watts JM, Waltz CS. The response of beef cattle to noise during handling. App Anim Behav Sci. 1999;62:27–42. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(98)00211-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Algers B, Jensen P. Teat stimulation and milk production during early lactation in sows: effects of continuous noise. Can J Anim Sci. 1991;71:51–60. doi: 10.4141/cjas91-006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grandin T. Assessment os stress during handling and transport. J Anim Sci. 1997;75:249–257. doi: 10.2527/1997.751249x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Albright JL, Arave CW. The behavior of cattle. New York: CAB International; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaneko JJ. Carbohydrate metabolism and its diseases. In: Kaneko JJ, Harvey WJ, Bruss LM, editors. Clinical biochemistry of domestic animals. 6. San Diego: Academic; 1997. pp. 45–81. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliveira LH, Nascimento AB, Monteiro PLJ, Guardieiro MM, Wiltbank MC, Sartori R. Development of insulin resistance in dairy cows by 150 days of lactation does not alter oocyte quality in smaller follicles. J Dairy Sci. 2016;99:9174–9183. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-10547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Staufenbiel R, Reinicke U, Panicke L. Investigations into glucose tolerance test in cattle. 1. Relations to stage of lactation and milk yield. Arch Tierz. 1999;42:45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 11.De Koster JD, Opsomer G. Insulin resistance in dairy cows. Vet Clin North Am Food Anim Pract. 2013;29:299–322. doi: 10.1016/j.cvfa.2013.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deepa PM, Dimri U, Jhambh R, Yatoo MI, Sharma B. Alteration in clinico-biochemical profile and oxidative stress indices associated with hyperglycaemia with special reference to diabetes in cattle—a pilot study. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2015;47:103–109. doi: 10.1007/s11250-014-0691-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abuelo A, Alves-Nores V, Hernandez J, Muiño R, Benedito JL, Castillo C. Effect of parenteral antioxidant supplementation during the dry period on postpartum glucose tolerance in dairy cows. J Vet Intern Med. 2016;30:892–898. doi: 10.1111/jvim.13922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.González-Grajales LA, Pieper L, Kremer J, Staufenbiel R. Influence of food deprivation on intravenous glucose tolerance test traits in Holstein Friesian heifers. J Dairy Sci. 2017;100:7710–7719. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-12133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.González-Grajales LA, Pieper L, Mengel S, Staufenbiel R. Evaluation of glucose dose on intravenous glucose tolerance test traits in Holstein-Friesian heifers. J Dairy Sci. 2018;101:774–782. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-13215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brouček J, Kovalcikova M, Kovalcik K. Effect of noise load on changes of biochemical indicators in differentently relative first-calf cows. Polnohospodarstvo. 1988;34:647–654. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pieper L, Staufenbiel R, Christ J, Panicke L, Müller U, Brockmann GA. Heritability of metabolic response to the intravenous glucose tolerance test in German Holstein Friesian bulls. J Dairy Sci. 2016;99:7240–7246. doi: 10.3168/jds.2015-10672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kremer J. Einfluss der Dauer der Nüchternzeit auf das Ergebnis im intravenösen Glukosetoleranztest beim weiblichen Jungrind [Doctoral dissertation] Berlin: Free University of Berlin; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Verga M, Luzi F, Carenzi C. Effects of husbandry and management systems on physiology and behaviour of farmed and laboratory rabbits. Horm Behav. 2007;52:122–129. doi: 10.1016/j.yhbeh.2007.03.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Basner M, Babisch W, Davis A, Brink M, Clark C, Janssen S, et al. Auditory and non-auditory effects of noise on health. Lancet. 2014;383:1325–1332. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61613-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thiesse L, Rudzik F, Pieren R, Wunderli JM, Spiegel K, Brink M, et al. eds. Short-term effects of nocturnal transportation noise on glucose metabolism. In: INTER-NOISE 45th international congress and exposition on noise control engineering; 2016; Hamburg, Germany.

- 22.Liu L, Wang F, Lu H, Cao S, Du Z, Wang Y, et al. Effects of noise exposure on systemic and tissue-level markers of glucose homeostasis and insulin resistance in male mice. Environ Health Perspect. 2016;124:1390–1398. doi: 10.1289/EHP162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lanier JL, Grandin T, Green RD, Avery D, McGee K. The relationship between reaction to sudden, intermittent movements and sounds and temperament. J Anim Sci. 2000;78:1467–1474. doi: 10.2527/2000.7861467x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boissy A, Bouissou M. Effects of androgen treatment on behavioral and physiological responses of heifers to fear-eliciting situations. Horm Behav. 1994;28:66–83. doi: 10.1006/hbeh.1994.1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tennessen T, Price MA, Berg RT. Comparative responses of bulls and steers to transportation. Can J Anim Sci. 1984;64:333–338. doi: 10.4141/cjas84-039. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schanbacher B, D’Occhio M. Hypothalamic control of the post-castration rise in serum LH concentrations in rams. J Reprod Fert. 1984;72:537–542. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0720537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wise ME, Rodriguez RE, Kelly CM. Gonadal regulation of LH secretion in prepubertal bull calves. Domest Anim Endocrinol. 1987;4:175–181. doi: 10.1016/0739-7240(87)90013-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen Y, Stookey J, Arsenault R, Scruten E, Griebel P, Napper S. Investigation of the physiological, behavioral, and biochemical responses of cattle to restraint stress. J Anim Sci. 2016;94:3240–3254. doi: 10.2527/jas.2016-0549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sjöström L, Garellick G, Krotkiewski M, Luyckx A. Peripheral insulin in response to the sight and smell of food. Metabolism. 1980;29:901–909. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(80)90031-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Simon C, Schlienger JL, Sapin R, Imler M. Cephalic phase insulin secretion in relation to food presentation in normal and overweight subjects. Physiol Behav. 1986;36:465–469. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(86)90316-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benthem L, Mundinger TO, Taborsky GJ. Meal-induced insulin secretion in dogs is mediated by both branches of the autonomic nervous system. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2000;278:E603–E610. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.2000.278.4.E603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Faverdin P. Variations de l`insulinémie en début de repas chez la vache en lactation. Reprod Nutr Dévelop. 1986;26:381–382. doi: 10.1051/rnd:19860267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Vasilatos R, Wangsness PJ. Changes in concentrations of insulin, growth hormone and metabolites in plasma with spontaneous feeding in lactating dairy cows. J Nutr. 1980;110:1479–1487. doi: 10.1093/jn/110.7.1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chase LE, Wangsness PJ, Martin RJ. Portal blood insulin and metabolite changes with spontaneous feeding in steers. J Dairy Sci. 1977;60:410–415. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(77)83880-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Herath CB, Reynolds GW, Mackenzie DDS, Davis SR, Harris PM. Vagotomy suppresses cephalic phase insulin release in sheep. Exp Physiol. 1999;84:559–569. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-445X.1999.01872.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lewis NJ. Frustation of goal-directed behaviour in swine. Appl Anim Behav Sci. 1999;64:19–29. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1591(99)00025-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.