Abstract

This study explored the association between exposure to acetaminophen during pregnancy and pubertal development using data from 15,822 boys and girls in the longitudinal Puberty Cohort, nested within the Danish National Birth Cohort. Use of acetaminophen was reported 3 times during pregnancy and 6 months postpartum. In total, 54% of mothers indicated use at least once during pregnancy. Between 2012 and 2017, sons and daughters provided information on a wide range of pubertal milestones—including Tanner stages, axillary hair growth, and age at menarche or voice break and first ejaculation—every 6 months from 11 years of age until full sexual maturation. Data were analyzed using a regression model for interval-censored data, providing adjusted mean monthly differences in age at attaining the pubertal milestones according to intrauterine cumulative (weeks) and trimester-specific acetaminophen exposure. Our results suggested a tendency towards slightly earlier attainment of almost all studied markers of female pubertal development with increasing number of weeks of exposure (i.e., about 1.5–3 months earlier age at pubic hair, axillary hair, and acne development comparing unexposed with those prenatally exposed for more than 12 weeks). Male pubertal development had no strong association with acetaminophen exposure.

Keywords: endocrine disrupters, prenatal exposure delayed effects, puberty, sex characteristics, Tanner stages

Use of over-the-counter analgesics, especially acetaminophen, has been steadily increasing in Western countries (1). Acetaminophen, also known as paracetamol, is now being used at least once by more than 50% of pregnant women in some countries (2–4). It is considered safe by the general public and remains a first choice for treatment for fever and pain during pregnancy (5).

Acetaminophen is, however, capable of crossing the placental barrier (6, 7) and might therefore interfere with organ development affecting health in the offspring, including reproductive health (8). Studies in rodents suggest that administration of acetaminophen equivalent to human therapeutic doses exerts antiandrogenic disruption, inhibiting early masculinization of male rats (9–12). On the other hand, an in vitro study of human fetal testicular tissue found no association between short-term exposure to acetaminophen and testosterone production (13). A recent study in rodents linked intrauterine exposure to acetaminophen with alterations in fetal germ cell development and differentiation, reducing later reproductive capacity in female—but not in male—offspring (14). Cohort studies on the associations between prenatal exposure to acetaminophen and anogenital distance support evidence from animal studies of antiandrogenic disruption in males but do not demonstrate a similar association in females (15, 16). In parallel, studies on male genital malformations show no associations with hypospadias and inconclusive results concerning cryptorchidism (9, 17–22). It remains largely unknown to what extent a potential endocrine programming disruption of intrauterine exposure to acetaminophen might affect long-term reproductive health, such as age at puberty timing. To our knowledge, this is the first study on puberty timing, and we hypothesize that intrauterine exposure to acetaminophen alters the timing of markers of male and female pubertal development.

METHODS

Study population

Our study used data from the large nationwide Puberty Cohort that is nested within the Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC) (23). The pregnant women in DNBC were recruited from 1996 to 2002. Half of all general practitioners in Denmark participated in the recruitment process, and about 60% of the pregnant women accepted the invitation handed out at their first antenatal visit. A self-administrated enrollment form and 4 computer-assisted telephone interviews on lifestyle during pregnancy and health of their children were carried out at approximately gestational weeks 17 and 32 as well as 6 and 18 months after birth.

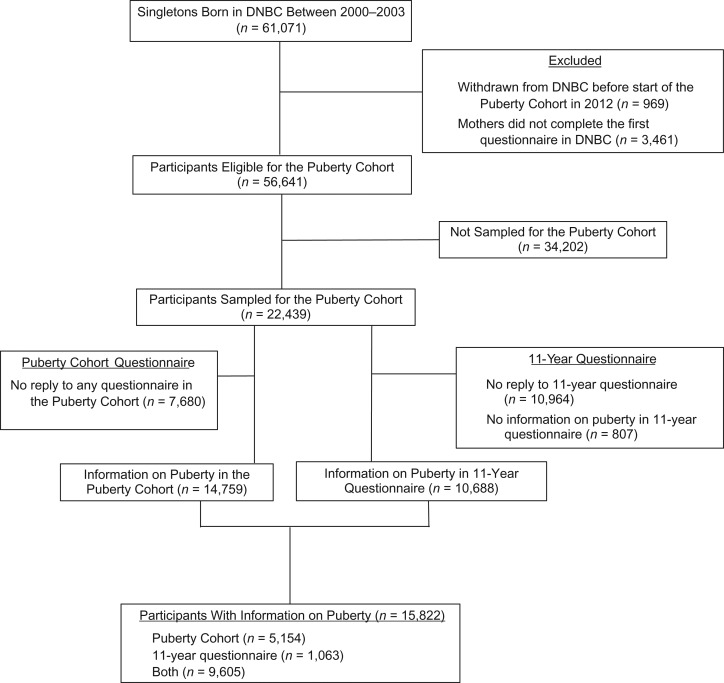

A total of 56,641 live-born singletons born to mothers in DNBC from 2000 to 2003 were eligible for participation in the Puberty Cohort. The mothers had responded to the first questionnaire in DNBC and not withdrawn their consent before 2012 (Figure 1). An oversampling strategy was used to create the Puberty Cohort, aiming to increase statistical efficiency by ensuring adequate samples sizes. We oversampled participants from subgroups of 12 pre- and perinatal exposures (27 sampling frames) considered to be of relevance for timing of puberty and paired these with a randomly selected reference group of 8,000 children (1 sampling frame), making up the Puberty Cohort of 22,439 children. The relevant pre- and perinatal exposures included maternal gestational use of acetaminophen.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of participants in the Puberty Cohort nested within the Danish National Birth Cohort (DNBC) (n = 15,822), Denmark, 2000–2017.

At 11.5 years of age, participating children were invited to provide information on their current stage of puberty every 6 months until they reached full sexual maturation or turned 18 years of age, whichever came first. Full sexual maturation was defined as self-reported Tanner stage 5 for both pubic hair growth and breast or genital development (24, 25).

To complement the information on puberty timing in the Puberty Cohort, we added data from an 11-year follow-up of all children in the DNBC. Altogether 10,668 children, subsequently sampled for the Puberty Cohort, responded to a comprehensive questionnaire that also included similar questions on pubertal development. In total, when data from the 11-year questionnaire was added, information on pubertal development of 15,822 children from the Puberty Cohort was available.

Exposure assessment

Information on use of acetaminophen was retrieved through the maternal enrollment form and 3 of the computer-assisted telephone interviews, covering use from 4 weeks before pregnancy until delivery. The enrollment form included questions on use of painkillers and specifications on timing of use until the 14th week of pregnancy. In the 3 telephone interviews, women were asked whether any kind of painkillers, available over-the-counter or via prescription, had been taken. If women answered “yes,” they were asked to identify the type of drug(s) from a list of the 44 most common types, including acetaminophen as a mono or combination drug. Further questions gave respondents the option to report use of painkillers or drugs not specified in the list, as well as to record intake or drugs used to treat rheumatic diseases, infections, fever, or inflammation. Further, the women were asked to specify in which gestational weeks they used each of the listed drugs. Because the women did not indicate the dose of the painkillers used, cumulative weeks of use indicated exposure level in this study.

Outcome measures

Information on pubertal development was collected by a translated version of a questionnaire developed by the British Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC) (26). The questionnaire is available at http://www.bsig.dk. The participants were asked every sixth month to report whether they had experienced the following pubertal milestones: axillary hair growth (yes/no), acne (yes/no), pubic hair growth and breast or genital development according to Tanner staging (1–5), first ejaculation (yes/no), first menstrual bleeding (yes/no), voice break (yes (sometimes), yes (definitive change), no, don’t know). If they answered “yes” to first ejaculation (boys) or first menstrual bleeding (girls), they were asked to provide age by year and months. Questions on pubic hair growth and breast or genital growth were guided by illustrations and explanatory texts for each of the Tanner stages (24, 25).

Covariates

Directed acyclic graphs were used to identify potential confounding factors a priori (27). The following potential confounders were prepregnancy body mass index, alcohol consumption in the first trimester, smoking in the first trimester, time to pregnancy, highest social class of parents, maternal age at menarche, maternal age at delivery, and parity. In order to partly control for confounding by indication, 3 variables describing conditions that might induce use of acetaminophen during pregnancy were further included in our models. These were fever during pregnancy, muscle or joint disease during pregnancy, and inflammation or infection during pregnancy. The categorization of the included potential confounders can be found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Maternal Characteristics According to Sons’ and Daughters’ Exposure to Acetaminophen at Least Once During Gestation, the Puberty Cohort (n = 15,822), Denmark, 2012–2017

| Covariatesa | Exposure to Acetaminophen | Total No. | Missing | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | Yes | ||||||

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| Total | 7,216 | 45.6 | 8,606 | 54.4 | 15,822 | ||

| Prepregnancy BMIb,c | 23.4 (4.4) | 24.2 (4.7) | 23.8 (4.6) | 217 | 1.4 | ||

| Alcohol consumption per week in first trimester, units | 22 | 0.1 | |||||

| 0 | 3,853 | 53.3 | 4,310 | 50.1 | 8,163 | ||

| >0–1 | 2,179 | 30.3 | 2,751 | 32.0 | 4,930 | ||

| >1–3 | 818 | 11.4 | 1,084 | 12.6 | 1,902 | ||

| >3 | 352 | 4.9 | 453 | 5.3 | 805 | ||

| No. of cigarettes daily in first trimesterc | 1.8 (4.2) | 2.2 (4.5) | 2.0 (4.3) | 53 | 0.3 | ||

| Time to pregnancy, including ART, months | 44 | 0.3 | |||||

| 0 | 1,380 | 19.2 | 1,656 | 19.3 | 3,036 | ||

| 1–2 | 1,331 | 18.5 | 1,621 | 18.9 | 2,952 | ||

| 3–5 | 1,158 | 16.1 | 1,398 | 16.3 | 2,556 | ||

| 6–12 | 97 | 13.5 | 1,067 | 12.4 | 2,038 | ||

| >12 | 539 | 7.5 | 703 | 8.2 | 1,242 | ||

| Use of ART | 702 | 9.8 | 762 | 8.9 | 1,464 | ||

| Not planned | 1,113 | 15.5 | 1,377 | 16.0 | 2,490 | ||

| Highest social class of parents | 31 | 0.2 | |||||

| High-grade professional | 1,706 | 23.7 | 1,984 | 23.1 | 3,690 | ||

| Low-grade professional | 2,375 | 33.0 | 2,821 | 32.8 | 5,196 | ||

| Skilled worker | 2,011 | 27.9 | 2,342 | 27.3 | 4,353 | ||

| Unskilled worker | 924 | 12.8 | 1,225 | 14.3 | 2,149 | ||

| Student | 145 | 2.0 | 167 | 1.9 | 312 | ||

| Economically inactive | 42 | 0.6 | 49 | 0.6 | 91 | ||

| Maternal age at menarche | 123 | 0.8 | |||||

| Earlier than peers | 1,724 | 24.1 | 2,288 | 26.7 | 4,012 | ||

| Same time as peers | 4,099 | 57.4 | 4,891 | 57.2 | 8,990 | ||

| Later than peers | 1,322 | 18.5 | 1,375 | 16.1 | 2,697 | ||

| Maternal age at delivery, yearsc | 30.7 (4.4) | 30.6 (4.4) | 30.6 (4.4) | 6 | 0.1 | ||

| Parity | 0 | 0.0 | |||||

| First child | 3,829 | 53.1 | 4,138 | 48.1 | 7,967 | ||

| Second or later child | 3,387 | 46.9 | 4,468 | 51.9 | 7,855 | ||

| Fever during pregnancy | 23 | 0.1 | |||||

| No | 5,657 | 78.5 | 5,758 | 67.0 | 11,415 | ||

| Yes | 1,551 | 21.5 | 2,833 | 33.0 | 4,384 | ||

| Muscle or joint disease during pregnancy | 7 | 0.1 | |||||

| No | 6,247 | 86.6 | 7,038 | 81.8 | 13,285 | ||

| Yes | 965 | 13.4 | 1,565 | 18.2 | 2,530 | ||

| Inflammation or infection during pregnancy | 261 | 1.6 | |||||

| No | 6,205 | 88.3 | 7,048 | 82.6 | 13,253 | ||

| Yes | 825 | 11.7 | 1,483 | 17.4 | 2,308 | ||

Abbreviations: ART, assisted reproductive techniques; BMI, body mass index.

a Numbers within each categorized covariate might not necessarily add up to the total number of participants due to missing data.

b Weight (kg)/height (m)2.

c Values are expressed as mean (standard deviation).

Information on parity and maternal age was retrieved from the Danish Medical Birth Register, and socioeconomic status, classified based on the International Standard Class of Occupation and Education codes (ISCO-88 and ISCED), was retrieved from Statistics Denmark. Information on the remaining confounders was available through the telephone interviews in DNBC.

Statistical analysis

The participants in the Puberty Cohort received the questionnaires half-yearly, which makes data on pubertal milestones censored. The statistical analyses were therefore carried out using a regression model for censored and normally distributed time-to-event data (intreg in Stata (StataCorp LLC, College Station, Texas)) to estimate mean monthly differences between exposure groups in age at attaining the pubertal milestones. The regression model is able to account for the left, right, or interval censoring of data assuming that the underlying distribution of the timing of a pubertal milestone is normal.

The assumption of normality was assessed by comparison of the stepwise cumulative incidence function and the cumulative incidence function based on the normal distribution using the R package icenReg (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The normal distribution fit the time of attained pubertal milestones very well. We also compared the nonparametric distribution to other waiting time distributions (Weibull, logistic, and log-normal), but the normal distribution gave the best fit. Residuals were calculated by subtracting the model mean to the left and right interval endpoints. The assumption of normality of these residuals was checked by a similar comparison further stratified by levels of included covariates.

We analyzed associations between intake of acetaminophen at least once during pregnancy and pubertal milestones using data from children with no recorded exposure during pregnancy as the unexposed referent. In the next analysis, age at attaining the pubertal milestones among children exposed in a cumulative number of weeks (1–2, 3–12, >12 weeks) was compared with age at attaining the milestones among the unexposed, and test for trend was conducted by fitting the number of weeks of exposure as a continuous variable. We further assessed timing of exposure comparing exposure only during the first (weeks 1–12 of gestation), second (weeks 13–24 of gestation), or third (week 25 of gestation until delivery) trimester and exposure in any 2 or all 3 trimesters with the unexposed.

The models were fitted with robust standard errors to account for clustering of siblings (n = 464 mothers) and sample as well as selection weights to address the sampling strategy and selective participation in the Puberty Cohort. The sampling weights estimate the inverse probability of being sampled for each individual in the Puberty Cohort according to the 28 different sampling frames. The selection weights estimate the inverse probability of participation according to a directed acyclic graph used to identify potential factors associated with participation in the Puberty Cohort a priori. Information on these factors, primarily related to socioeconomic conditions, were available as described above.

We conducted 2 subanalyses to further address confounding by indication. First, the analyses were restricted to mothers who did not report any of the 3 mentioned indications. Second, we performed analyses with the exclusion of mothers who took acetaminophen for more than 24 weeks of gestation (3%), because heavy use of acetaminophen during pregnancy might be more common in women suffering from chronic diseases causing pain. Because gestational weight gain might act as a potential confounder by altering infant size at birth (28), we repeated our analyses including gestational weight gain as an additional continuous covariate. To address the risk of type-1 errors due to multiple testing, we performed a test for the overall association with all puberty markers using the Huber-White robust variance estimation applied on the univariate marker models, which accounts for the correlations structure between the pubertal markers (29, 30). These subanalyses were performed for cumulative weeks of exposure.

Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata/MP, version 13.1 (StataCorp LLC), and R x64, version 3.3.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Ethical approval

The Committee for Biomedical Research Ethics in Denmark has approved data collection in DNBC ((KF) 01-471/94). A written informed consent was obtained from mothers upon recruitment covering both mother’s and offspring’s participation until the children turned 18 years of age. The present study was approved by the steering committee of DNBC (2012-04 and 2015-47) and the Danish Data Protection Agency (2012-41-0379 and 2015-57-0002).

RESULTS

Of the 22,439 children invited to participate in the Puberty cohort, 15,822 (approximately 71%), 7,697 boys and 8,125 girls, have returned at least 1 and up to 11 questionnaires each (Figure 1). Use of acetaminophen was not related to participation in the Puberty Cohort. The responders were, by March 2017, between 14 and 17 years of age, and 4,317 had reached full sexual maturity (27%). Among the 15,822 participants, 8,606 (54%) were exposed to acetaminophen at least once during gestation. Table 1 shows that prepregnancy body mass index, parity, and reports of the 3 potential indications were higher in mothers with any gestational intake of acetaminophen. In addition, maternal smoking and alcohol intake during the first trimester were more frequent in this group.

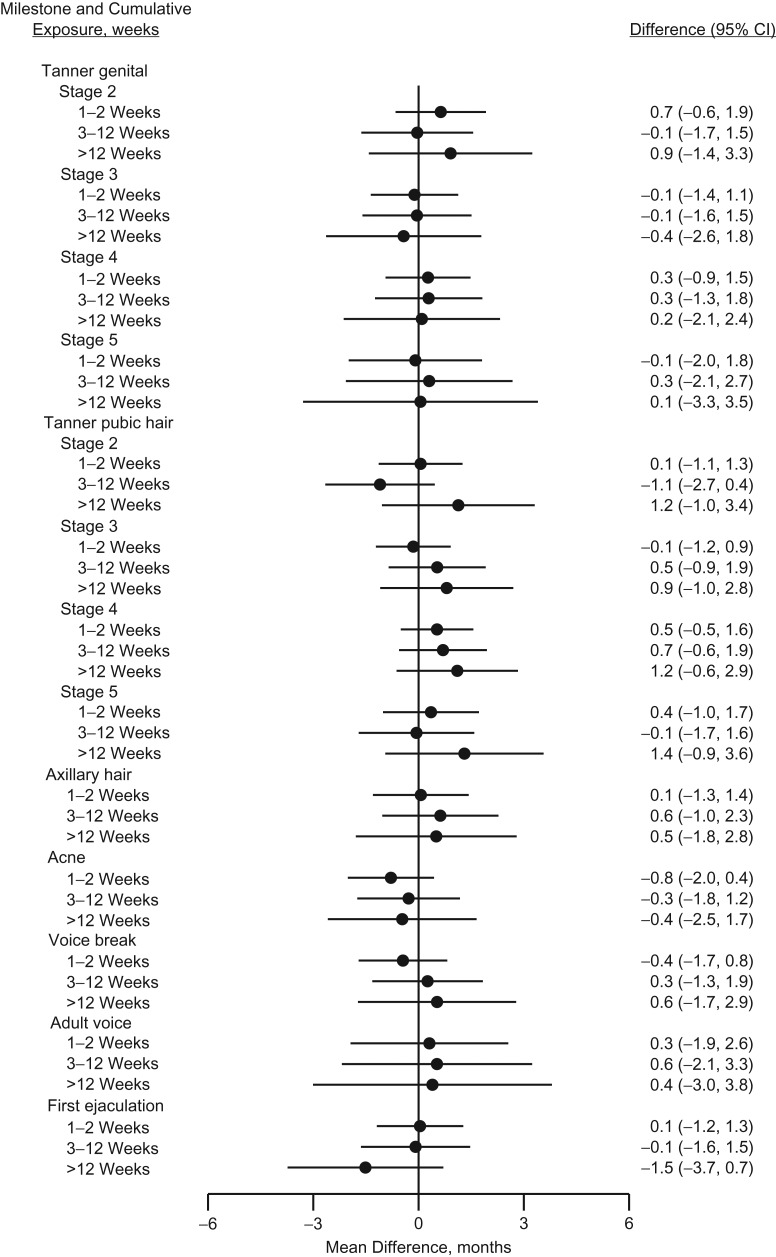

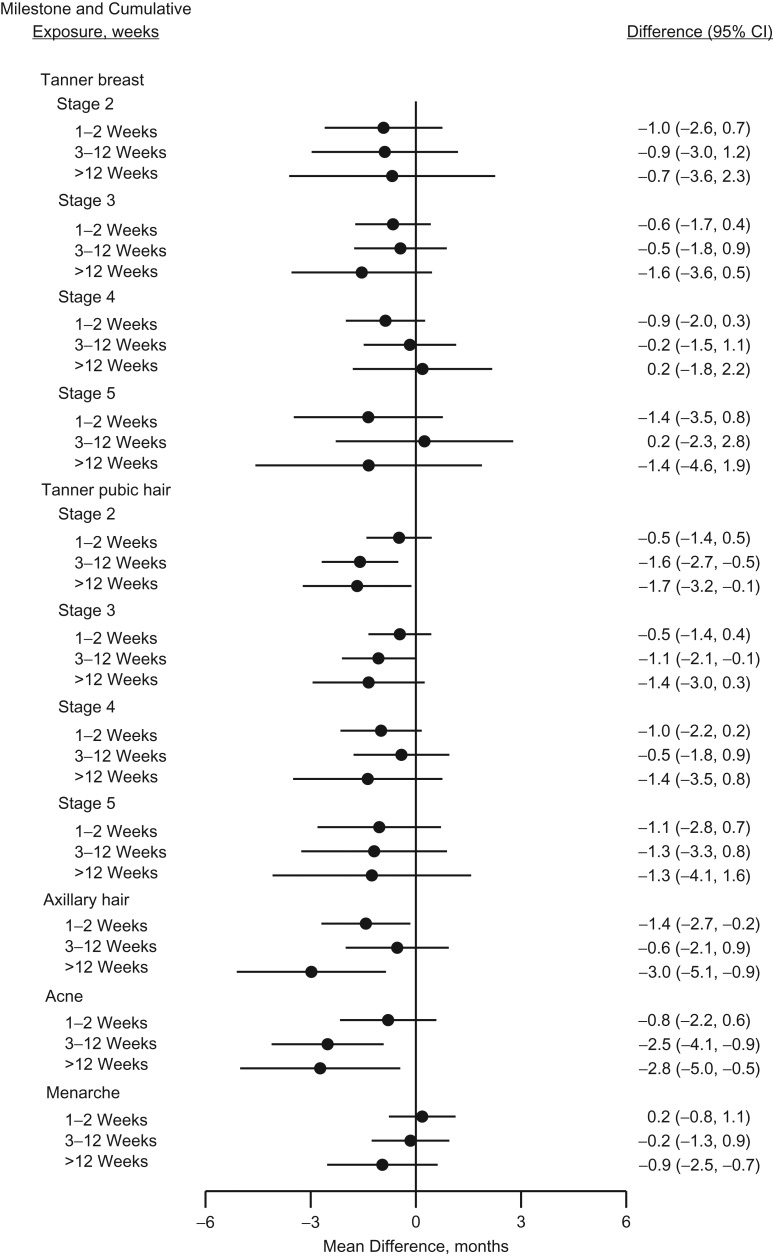

Table 2 presents the mean ages in years at attaining various male and female pubertal milestones for an unexposed reference person as well as the mean monthly differences between those who were and who were not exposed to acetaminophen at least once during fetal life. The crude estimates suggested a tendency towards earlier age at pubertal timing in exposed boys, which was attenuated in the adjusted analyses. In exposed girls, a more consistent tendency towards slightly earlier age at pubertal timing was observed. The tendency was, however, most pronounced for axillary hair growth, with −1.2 (95% confidence interval (CI): −2.2, −0.2), and occurrence of acne, with −1.7 (95% CI: −2.7, −0.6) months earlier age at attainment. Analyses of cumulative number of weeks with exposure to acetaminophen during pregnancy are presented in Figures 2 and 3 (and Web Table 1, available at https://academic.oup.com/aje) as adjusted monthly differences between exposure groups. We observed no strong indication of a pattern with increasing number of weeks of exposure in boys, although all of the Tanner pubic hair stages were to some extent shifted towards later age at attainment in boys exposed for more than 12 weeks. A somewhat consistent pattern was observed among girls, associating longer duration of intrauterine acetaminophen exposure with earlier age at attaining almost all studied markers of pubertal development, but with wide confidence intervals. The magnitudes of the observed associations were largest for stage 2 of Tanner pubic hair (difference, months = −1.7, 95% CI: −3.2, −0.1), axillary hair growth (difference, months = −3.0, 95% CI: −5.1, −0.9), and occurrence of acne (difference, months = −2.8, 95% CI: −5.0, −0.5) in the group of girls exposed to acetaminophen for more than 12 weeks.

Table 2.

Mean Differences in Age at Attaining Various Pubertal Milestones According to Exposure to Acetaminophen at Least Once During Gestation, the Puberty Cohort, Denmark, 2012–2017

| Pubertal Milestone | No. of Personsa | Exposure to Acetaminophen | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nob | Yesc | |||||

| Mean Age, years | 95% CI | Crude | Adjustedd | |||

| Mean Difference | Mean Difference | 95% CI | ||||

| Boys | ||||||

| Tanner stage, genitals | ||||||

| Stage 2 | 7,469 | 11.2 | 10.5, 11.9 | −0.3 | 0.0 | −1.0, 1.0 |

| Stage 3 | 7,469 | 12.7 | 11.9, 13.5 | −0.7 | −0.2 | −1.2, 0.8 |

| Stage 4 | 7,469 | 13.7 | 12.0, 14.4 | −0.4 | 0.1 | −0.9, 1.0 |

| Stage 5 | 7,469 | 15.2 | 14.3, 16.0 | −0.4 | 0.3 | −1.2, 1.8 |

| Tanner stage, pubic hair | ||||||

| Stage 2 | 7,473 | 11.7 | 11.0, 12.4 | −0.7 | −0.3 | −1.2, 0.7 |

| Stage 3 | 7,473 | 12.7 | 12.0, 13.4 | −0.5 | 0.1 | −0.7, 1.0 |

| Stage 4 | 7,473 | 13.7 | 13.2, 14.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 | −0.2, 1.4 |

| Stage 5 | 7,473 | 14.9 | 14.4, 15.4 | −0.3 | 0.2 | −0.8, 1.3 |

| Axillary hair | 7,478 | 13.5 | 12.7, 14.3 | −0.2 | 0.4 | −0.7, 1.4 |

| Acne | 7,478 | 11.5 | 10.9, 12.2 | −0.8 | −0.3 | −1.3, 0.6 |

| Voice break | 7,274 | 13.1 | 12.4, 13.8 | −0.5 | 0.1 | −0.9, 1.1 |

| Adult voice | 7,274 | 14.4 | 13.1, 15.6 | −0.4 | 0.5 | −1.2, 2.2 |

| First ejaculation | 7,465 | 13.5 | 12.9, 14.2 | −0.7 | −0.3 | −1.2, 0.7 |

| Girls | ||||||

| Tanner stage, breast | ||||||

| Stage 2 | 7,888 | 10.7 | 9.9, 11.5 | −1.3 | −0.7 | −2.0, 0.7 |

| Stage 3 | 7,888 | 12.1 | 11.5, 12.7 | −1.2 | −0.6 | −1.4, 0.3 |

| Stage 4 | 7,888 | 13.4 | 12.7, 14.1 | −1.0 | −0.3 | −1.3, 0.6 |

| Stage 5 | 7,888 | 16.0 | 15.1, 17.0 | −1.5 | −0.4 | −2.1, 1.2 |

| Tanner stage, pubic hair | ||||||

| Stage 2 | 7,889 | 11.4 | 10.9, 11.9 | −1.0 | −0.7 | −1.5, 1.2 |

| Stage 3 | 7,889 | 12.9 | 12.5, 13.3 | −0.9 | −0.6 | −1.3, 0.1 |

| Stage 4 | 7,889 | 13.8 | 13.4, 14.3 | −1.0 | −0.7 | −1.6, 0.2 |

| Stage 5 | 7,889 | 15.7 | 14.9, 16.5 | −1.3 | −0.8 | −2.1, 0.6 |

| Axillary hair | 7,894 | 12.2 | 11.6, 12.9 | −1.7 | −1.2 | −2.2, −0.2 |

| Acne | 7,894 | 11.9 | 11.4, 12.5 | −2.1 | −1.7 | −2.7, −0.6 |

| Menarche | 7,886 | 13.4 | 12.9, 13.8 | −0.7 | −0.1 | −0.8, 0.7 |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval.

a Number of persons included in analysis for each milestone.

b Mean age in years at attaining pubertal milestones for a given reference person with no exposure to acetaminophen: prepregnancy BMI of 18.5 (calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2), 0 alcohol units per week in first trimester, 0 cigarettes daily in first trimester, 0 months time to pregnancy, highest social class of parents was high-grade professional, maternal age of menarche same as peers, maternal age at delivery of 30.7 years, parity: first child, no fever during pregnancy, no muscle or joint disease during pregnancy, and no inflammation or infection during pregnancy.

c Mean difference (months) at attaining milestone between unexposed and exposed.

d Adjusted for prepregnancy BMI, alcohol units per week in first trimester, daily number of cigarettes in first trimester, time to pregnancy, highest social class of parents, maternal age of menarche, maternal age at delivery, parity, fever during pregnancy, muscle or joint disease during pregnancy, and inflammation or infection during pregnancy.

Figure 2.

Adjusted mean differences (months, 95% confidence intervals (CIs)) in age at attaining various pubertal milestones in boys according to number of weeks with exposure to acetaminophen during gestation, the Puberty Cohort, Denmark, 2012–2017.

Figure 3.

Adjusted mean differences (months, 95% confidence intervals (CIs)) in age at attaining various pubertal milestones in girls according to number of weeks with exposure to acetaminophen during gestation, the Puberty Cohort, Denmark, 2012–2017.

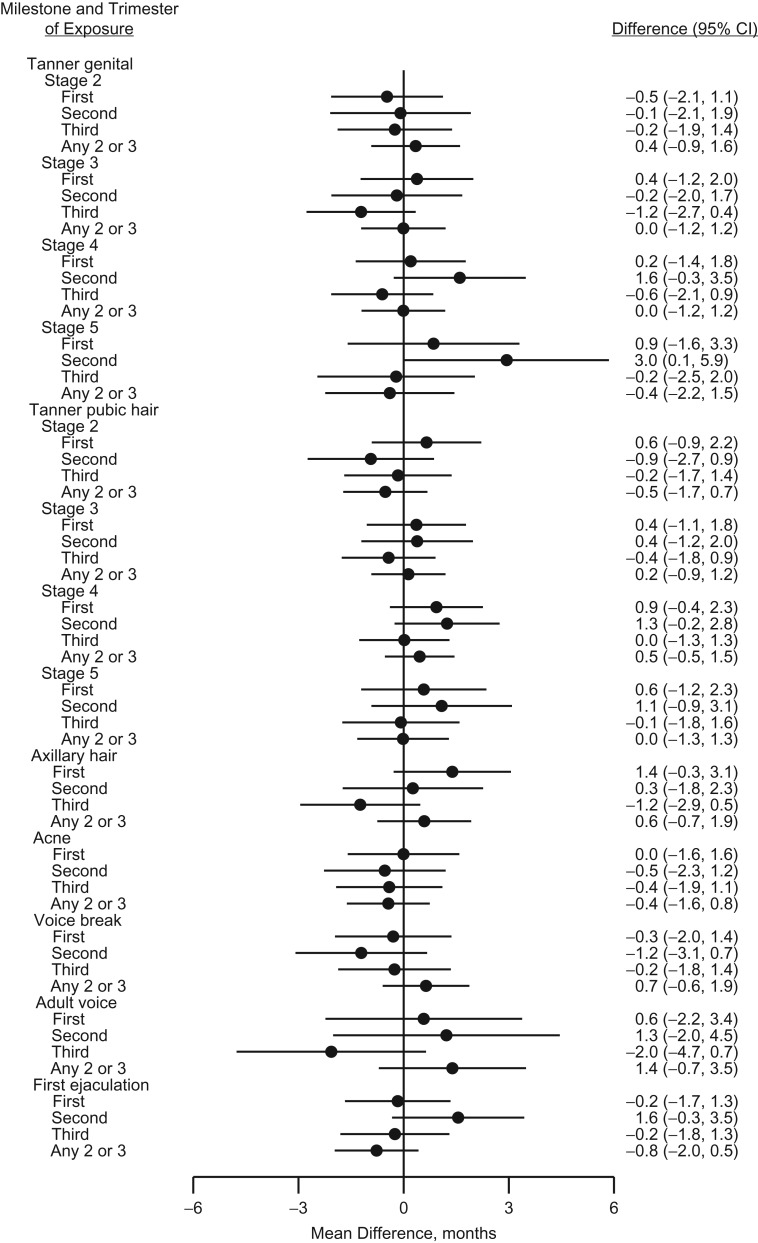

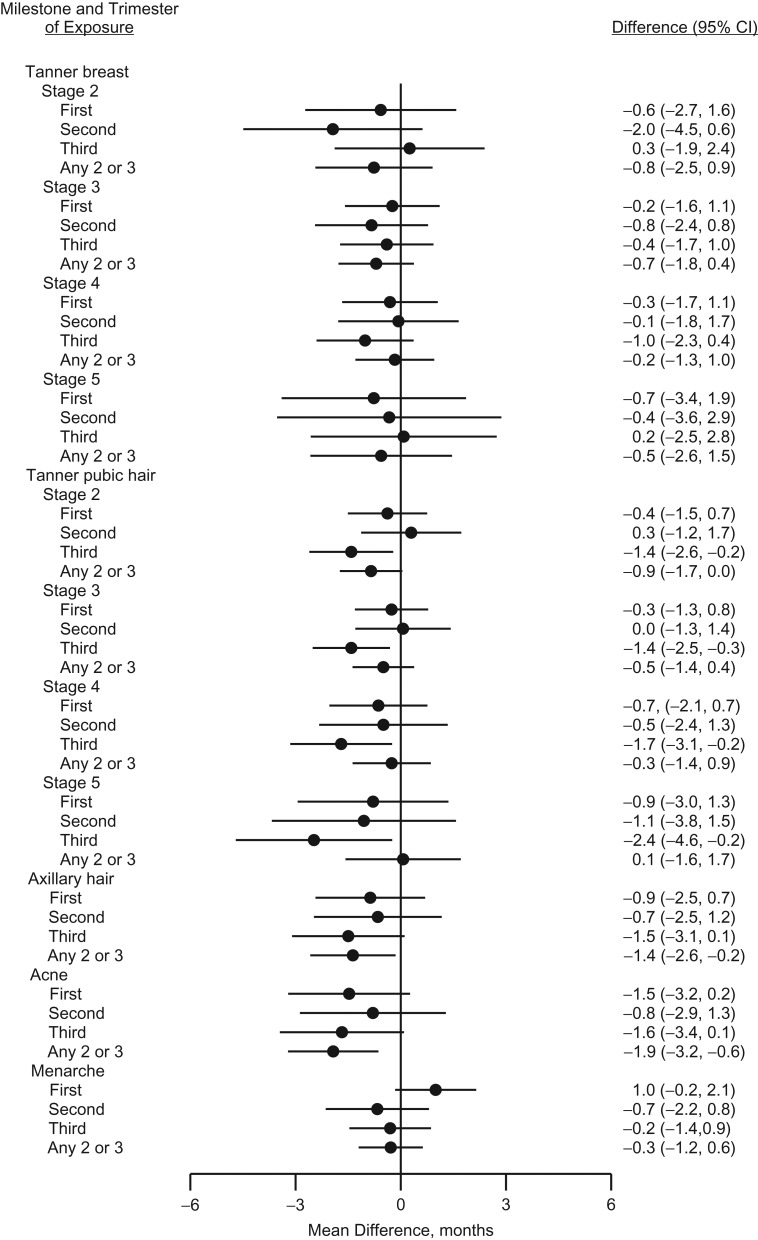

The analyses on timing of exposure by trimester showed no specific pattern in boys (Figure 4 and Web Table 2). In girls, breast development was independent of the specific timing of exposure, whereas pubic hair development and to a lesser degree axillary hair growth and occurrence of acne were skewed towards earlier age at attainment in girls with exposure in one of the trimesters. These tendencies were most pronounced in girls exposed only in the third trimester (Figure 5 and Web Table 2).

Figure 4.

Adjusted mean differences (months, 95% confidence intervals (CIs)) in age at attaining various pubertal milestones in boys according to trimester of exposure to acetaminophen during gestation, the Puberty Cohort, Denmark, 2012–2017.

Figure 5.

Adjusted mean differences (months, 95% confidence intervals (CIs)) in age at attaining various pubertal milestones in girls according to trimester of exposure to acetaminophen during gestation, the Puberty Cohort, Denmark, 2012–2017.

In the analyses restricted to mothers who did not report any of the 3 conditions associated with acetaminophen intake, results were similar to those presented for the binary and trimester-specific exposure to acetaminophen. The tendency towards earlier age at female pubic hair development, however, strengthened in the analyses with cumulative weeks of exposure (data not shown). Analyses with exclusion of heavy acetaminophen users did not change our results substantially. In the analyses with cumulative weeks of exposure, however, female axillary hair growth and occurrence of acne were further shifted towards earlier age at attainment among those who were highly exposed (more than 12 weeks of gestation) (data not shown). Our subanalyses with additional adjustment for gestational weight gain did not change the results (data not shown). Using robust variance estimation to perform a single test, cumulative number of weeks with exposure was associated with earlier female puberty timing (P = 0.04).

DISCUSSION

Results from our population-based cohort study suggest that intrauterine exposure to acetaminophen might be associated with slightly earlier attainment of almost all studied female markers of pubertal development, although most pronounced for pubic hair growth, axillary hair growth, and occurrence of acne, but with wide confidence intervals. On the other hand, estimates for boys were randomly scattered around the null hypothesis, indicating limited if any evidence for an association between intrauterine exposure to acetaminophen and male pubertal development. These findings were supported by a test of the overall association between exposure and all puberty markers. We were not able to identify specific vulnerable exposure windows. Our results suggest that those exposed to acetaminophen during fetal life might exhibit sex-specific endocrine disruptive effects in relation to pubertal development.

Prior studies have mainly addressed whether in utero exposure to acetaminophen interferes with neurodevelopment and cognition (2, 4, 31–37), asthma (38), markers of short-term reproductive health, such as risk of some congenital anomalies (9, 17–22), and differences in anogenital distance (15, 16). Intrauterine exposure to acetaminophen might interfere with important fetal developmental processes regulated by prostaglandins (12, 14, 39) and/or exert direct inhibitory effects on fetal testosterone production (9, 10). However, it remains unknown to what extent such potential effects are translatable to humans and might induce long-lasting effects on the complex neuroendocrine system that regulates pubertal development and which parts of the regulatory system might be susceptible to acetaminophen exposure.

Puberty is initiated by a reactivation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis that stimulates androgen production, causing testicular and pubic hair growth in boys, and stimulates ovarian estrogen production, causing breast enlargement and menarche in girls. Girls’ pubic and axillary hair growth are initially regulated by androgens from the adrenal glands, and at later stages of puberty, hair growth becomes hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal-dependent (40, 41). Earlier age at onset of pubic and axillary hair growth in girls, as seen in our study, might suggest that acetaminophen interferes with peripheral androgen production rather than inducing hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis dysfunction. However, if acetaminophen also exerts peripheral antiandrogenic effects, lack of androgen would be expected to delay rather than accelerate puberty in girls.

Major strengths of the study are the high participation rate and the use of a variety of different markers of pubertal development. Further, information on exposure and pubertal development was collected close to the time of the event (23, 42). The participants ranked their current pubertal stage by a wide range of markers every 6 months beginning at age 11 years. A large proportion of the boys and girls had already experienced some of the early puberty stages at inclusion. Our regression model was, however, able to account for the censoring of data assuming that the underlying distribution of the timing of pubertal milestones is normal. A recent consensus paper strongly recommended the use of these types of regression models in longitudinal studies with repeated measures of pubertal development (43).

We used self-administrated questionnaires, including Tanner rating scales, to assess pubertal development. Although studies on the reliability of self-assessment of pubertal development using Tanner staging have been conflicting (44–47), any potential misclassification would most likely be nondifferential in this study. Further, self-reporting of pubertal development serves as a cost- and timing-savings tool in large longitudinal cohorts such as the Puberty Cohort that do not pose the same strong risk of selection bias compared with clinical examinations.

Information on use of acetaminophen was collected prior to outcome occurrence, including details on timing and duration of use. Lack of information and recall bias are therefore expected to be independent of later pubertal development. We used time of interview to assign trimester-specific exposure when mothers stated that they took acetaminophen but were unable to specify timing of use. In addition, 2,357 interviewees (15%) were unable to identify intake on a weekly basis, thereby introducing some uncertainty to the analyses on cumulative exposure. Moreover, the grouping of number of weeks of exposure was a crude indicator for cumulative duration of exposure, because it does not take into account the frequencies of use. This misclassification would often lead to an underestimation of the effect sizes.

Similarly, we were not able to account for the frequencies of use in the analyses with timing of exposure. Further, by combining intake of acetaminophen in any 2 or all 3 trimesters into one category, effects of cumulative and time-specific exposure to acetaminophen might be difficult to separate. We believe, however, that by comparing children with no exposure to children with exposure in one specific trimester, we provide some insight into potential vulnerable exposure windows.

We used inverse probability weighting to account for the sampling procedure and nonresponse and controlled for several potential confounders. Use of acetaminophen was, as expected, more common in pregnant women who reported episodes of inflammation or infection, fever, or musculoskeletal disorders. In subanalyses restricted to women with no reports of these indications, cumulative number of weeks with exposure was more strongly associated with earlier age at attaining pubic hair development, especially for children with more than 12 weeks of exposure. This finding could be partially explained by similar indications among this group of mothers, because these indications were slightly associated with earlier puberty timing in our data. A prolonged use of acetaminophen during pregnancy is more common in women suffering from chronic diseases such as rheumatic diseases, but we are not aware of studies that have investigated whether this chronic disease is associated with pubertal development. However, exclusion of heavy users of acetaminophen, defined as use for more than 24 weeks of gestation (3%), did not change our results substantially. Still, we cannot exclude the possibility that residual confounding by indication or unmeasured confounding factors might serve as alternative explanations, although that would require that these factors are also strong risk factors for earlier pubertal development in girls. A potential confounding factor could be unmeasured, poor, family-related lifestyle behavior that increased maternal intake of acetaminophen and accelerated pubertal timing by increasing the risk of high childhood body mass index. To examine the potential impact of residual confounding by indication from conditions for long-term use and unmeasured confounding from, for example, poor overall health, we conducted a multidimensional bias analysis using the approach suggested by VanderWeele and Arah (48). Even after applying realistic scenarios for female axillary hair growth, the impact of potential bias was minimal. Description and results of this analysis are found in the Web material (Web Appendix 1 and Web Table 3).

In conclusion, our study suggests a tendency towards earlier female pubertal development with increasing number of weeks of intrauterine exposure to acetaminophen but seems to show no strong associations, if any, with male pubertal development. The results suggest that acetaminophen might interfere with prenatal, sex-specific developmental processes that lead to long-term effects on pubertal development. Although the observed shifts in female puberty timing were minor, these findings could signal other endocrine-related changes that might have later reproductive and health disadvantages, as suggested by others (49–52).

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Author affiliations: Section for Epidemiology, Department of Public Health, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark (Andreas Ernst, Nis Brix, Lea L.B. Lauridsen, Cecilia H. Ramlau-Hansen); Department of Epidemiology, Fielding School of Public Health, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, California (Andreas Ernst, Nis Brix, Jørn Olsen, Zeyan Liew); Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark (Jørn Olsen); Section for Biostatistics, Department of Public Health, Aarhus University, Aarhus, Denmark (Erik T. Parner); and Section for Paediatric Urology, Department of Urology, Aarhus University Hospital, Aarhus, Denmark (Lars H. Olsen).

This work was supported by the Danish Council for Independent Research (DFF 4183-00152 to C.H.R-.H.) and the Faculty of Health at Aarhus University. The Danish National Birth Cohort was established with a significant grant from the Danish National Research Foundation. Additional support was obtained from the Danish Regional Committees, the Pharmacy Foundation, the Egmont Foundation, the March of Dimes Birth Defects Foundation, the Health Foundation, and other minor grants. The DNBC Biobank has been supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation and the Lundbeck Foundation. Follow-up of mothers and children has been supported by the Danish Medical Research Council (grants SSVF 0646, 271-08-0839/06-066023, O602-01042B, 0602-02738B), the Lundbeck Foundation (grants 195/04 and R100-A9193), the Innovation Fund Denmark (grant 0603-00294B (09-067124)), the Nordea Foundation (grant 02-2013-2014), Aarhus Ideas (grant AU R9-A959-13-S804). University of Copenhagen (Strategic Grant IFSV 2012), and the Danish Council for Independent Research (grants DFF–4183-00594 and DFF–4183-00152).

Conflict of interest: none declared.

Abbreviations

- CI

confidence interval

- DNBC

Danish National Birth Cohort.

REFERENCES

- 1. Hudec R, Božeková L, Tisoňová J. Consumption of three most widely used analgesics in six European countries. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2012;37(1):78–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brandlistuen RE, Ystrom E, Nulman I, et al. Prenatal paracetamol exposure and child neurodevelopment: a sibling-controlled cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2013;42(6):1702–1713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Werler MM, Mitchell AA, Hernandez-Diaz S, et al. Use of over-the-counter medications during pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193(3 pt 1):771–777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Liew Z, Ritz B, Rebordosa C, et al. Acetaminophen use during pregnancy, behavioral problems, and hyperkinetic disorders. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(4):313–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Black RA, Hill DA. Over-the-counter medications in pregnancy. Am Fam Physician. 2003;67(12):2517–2524. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Syme MR, Paxton JW, Keelan JA. Drug transfer and metabolism by the human placenta. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2004;43(8):487–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rayburn W, Shukla U, Stetson P, et al. Acetaminophen pharmacokinetics: comparison between pregnant and nonpregnant women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1986;155(6):1353–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kristensen DM, Mazaud-Guittot S, Gaudriault P, et al. Analgesic use—prevalence, biomonitoring and endocrine and reproductive effects. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2016;12(7):381–393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kristensen DM, Hass U, Lesné L, et al. Intrauterine exposure to mild analgesics is a risk factor for development of male reproductive disorders in human and rat. Hum Reprod. 2011;26(1):235–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kristensen DM, Lesné L, Le Fol V, et al. Paracetamol (acetaminophen), aspirin (acetylsalicylic acid) and indomethacin are anti-androgenic in the rat foetal testis. Int J Androl. 2012;35(3):377–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gupta C. The role of prostaglandins in masculine differentiation: modulation of prostaglandin levels in the differentiating genital tract of the fetal mouse. Endocrinology. 1989;124(1):129–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. van den Driesche S, Macdonald J, Anderson RA, et al. Prolonged exposure to acetaminophen reduces testosterone production by the human fetal testis in a xenograft model. Sci Transl Med. 2015;7(288):288ra80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Mazaud-Guittot S, Nicolas Nicolaz C, Desdoits-Lethimonier C, et al. Paracetamol, aspirin, and indomethacin induce endocrine disturbances in the human fetal testis capable of interfering with testicular descent. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(11):E1757–E1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dean A, van den Driesche S, Wang Y, et al. Analgesic exposure in pregnant rats affects fetal germ cell development with inter-generational reproductive consequences. Sci Rep. 2016;6:19789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Fisher BG, Thankamony A, Hughes IA, et al. Prenatal paracetamol exposure is associated with shorter anogenital distance in male infants. Hum Reprod. 2016;31(11):2642–2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Lind DV, Main KM, Kyhl HB, et al. Maternal use of mild analgesics during pregnancy associated with reduced anogenital distance in sons: a cohort study of 1027 mother-child pairs. Hum Reprod. 2017;32(1):223–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Snijder CA, Kortenkamp A, Steegers EA, et al. Intrauterine exposure to mild analgesics during pregnancy and the occurrence of cryptorchidism and hypospadia in the offspring: the Generation R Study. Hum Reprod. 2012;27(4):1191–1201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Lind JN, Tinker SC, Broussard CS, et al. Maternal medication and herbal use and risk for hypospadias: data from the National Birth Defects Prevention Study, 1997–2007. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22(7):783–793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jensen MS, Henriksen TB, Rebordosa C, et al. Analgesics during pregnancy and cryptorchidism: additional analyses. Epidemiology. 2011;22(4):610–612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Jensen MS, Rebordosa C, Thulstrup AM, et al. Maternal use of acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and acetylsalicylic acid during pregnancy and risk of cryptorchidism. Epidemiology. 2010;21(6):779–785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Rebordosa C, Kogevinas M, Horváth-Puhó E, et al. Acetaminophen use during pregnancy: effects on risk for congenital abnormalities. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(2):178.e1–178.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wagner-Mahler K, Kurzenne JY, Delattre I, et al. Prospective study on the prevalence and associated risk factors of cryptorchidism in 6246 newborn boys from Nice area, France. Int J Androl. 2011;34(5 pt 2):e499–e510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Olsen J, Melbye M, Olsen SF, et al. The Danish National Birth Cohort—its background, structure and aim. Scand J Public Health. 2001;29(4):300–307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in pattern of pubertal changes in girls. Arch Dis Child. 1969;44(235):291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Variations in the pattern of pubertal changes in boys. Arch Dis Child. 1970;45(239):13–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Monteilh C, Kieszak S, Flanders WD, et al. Timing of maturation and predictors of Tanner stage transitions in boys enrolled in a contemporary British cohort. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2011;25(1):75–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pearl J. Causality: Models, Reasoning and Inference. 2nd ed Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nohr EA, Vaeth M, Baker JL, et al. Combined associations of prepregnancy body mass index and gestational weight gain with the outcome of pregnancy. Am J Clin Nutr. 2008;87(6):1750–1759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. White H. A heteroskedasticity-consistent covariance matrix estimator and a direct test for heteroskedasticity. Econometrica. 1980;48(4):817–838. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Huber PJ. The behavior of maximum likelihood estimates under nonstandard conditions. Presented at the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Berkeley, CA, June 21–July 18, 1965 and December 27, 1965–January 7, 1966.

- 31. Liew Z, Bach CC, Asarnow RF, et al. Paracetamol use during pregnancy and attention and executive function in offspring at age 5 years. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(6):2009–2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liew Z, Ritz B, Virk J, et al. Prenatal use of acetaminophen and child IQ: a Danish cohort study. Epidemiology. 2016;27(6):912–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bornehag CG, Reichenberg A, Hallerback MU, et al. Prenatal exposure to acetaminophen and children’s language development at 30 months. Eur Psychiatry. 2018;51:98–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Stergiakouli E, Thapar A, Davey Smith G. Association of acetaminophen use during pregnancy with behavioral problems in childhood: evidence against confounding. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(10):964–970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Thompson JM, Waldie KE, Wall CR, et al. Associations between acetaminophen use during pregnancy and ADHD symptoms measured at ages 7 and 11 years. PLoS One. 2014;9(9):e108210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Vlenterie R, Wood ME, Brandlistuen RE, et al. Neurodevelopmental problems at 18 months among children exposed to paracetamol in utero: a propensity score matched cohort study. Int J Epidemiol. 2016;45(6):1998–2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ystrom E, Gustavson K, Brandlistuen RE, et al. Prenatal exposure to acetaminophen and risk of ADHD. Pediatrics. 2017;140(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Cheelo M, Lodge CJ, Dharmage SC, et al. Paracetamol exposure in pregnancy and early childhood and development of childhood asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Dis Child. 2015;100(1):81–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Bayne RA, Eddie SL, Collins CS, et al. Prostaglandin E2 as a regulator of germ cells during ovarian development. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(10):4053–4060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ebling FJ. The neuroendocrine timing of puberty. Reproduction. 2005;129(6):675–683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Grumbach MM. The neuroendocrinology of human puberty revisited. Horm Res. 2002;57(suppl 2):2–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Rockett JC, Lynch CD, Buck GM. Biomarkers for assessing reproductive development and health: part 1–pubertal development. Environ Health Perspect. 2004;112(1):105–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Euling SY, Herman-Giddens ME, Lee PA. Examination of US puberty-timing data from 1940 to 1994 for secular trends: panel findings. Pediatrics. 2008;121(suppl 3):S172–S191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Duke PM, Litt IF, Gross RT. Adolescents’ self-assessment of sexual maturation. Pediatrics. 1980;66(6):918–920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Chan NP, Sung RY, Kong AP, et al. Reliability of pubertal self-assessment in Hong Kong Chinese children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2008;44(6):353–358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Desmangles JC, Lappe JM, Lipaczewski G, et al. Accuracy of pubertal Tanner staging self-reporting. J Pediatr Endocrinol Metab. 2006;19(3):213–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Hergenroeder AC, Hill RB, Wong WW, et al. Validity of self-assessment of pubertal maturation in African American and European American adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 1999;24(3):201–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. VanderWeele TJ, Arah OA. Bias formulas for sensitivity analysis of unmeasured confounding for general outcomes, treatments, and confounders. Epidemiology. 2011;22(1):42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Berkey CS, Frazier AL, Gardner JD, et al. Adolescence and breast carcinoma risk. Cancer. 1999;85(11):2400–2409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Moss AR, Osmond D, Bacchetti P, et al. Hormonal risk factors in testicular cancer. A case-control study. Am J Epidemiol. 1986;124(1):39–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Frontini MG, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Longitudinal changes in risk variables underlying metabolic Syndrome X from childhood to young adulthood in female subjects with a history of early menarche: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003;27(11):1398–1404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK, et al. The relation of menarcheal age to obesity in childhood and adulthood: the Bogalusa Heart Study. BMC Pediatr. 2003;3:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.