Abstract

Background

As the number of patients with hypertension who have obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) might be underestimated, this study aimed to explore the prevalence of OSA and develop a diagnostic algorithm for moderate or severe OSA among primary care (PC) patients with hypertension.

Methods

This multicenter cross‐sectional study enrolled patients diagnosed with hypertension aged 18 years or older in Japan from October 2012 to September 2014.

Results

Forty‐nine patients (64.5%) had 22 or more obstructive respiratory events during sleep.

Conclusions

The prevalence of OSA among PC patients with hypertension might be much higher than previously thought.

Keywords: classification and regression tree analysis, hypertension, obstructive sleep apnea

1. INTRODUCTION

Hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) are both common conditions in the general population. Recent studies have estimated 30%‐50% of patients with hypertension have OSA which might be underestimated, though the prevalence in the PC setting is unclear.1, 2, 3, 4

Understanding the prevalence and characteristics of OSA in PC patients with hypertension enables us to develop efficient diagnostic strategies. These strategies could improve the quality of hypertension and sleep disorder management in PC setting. Thus, our study aimed to explore the prevalence and characteristics of OSA in patients with hypertension and develop a diagnostic algorithm for unrecognized moderate or severe OSA in patients with hypertension in the PC setting.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

In this multicenter cross‐sectional study, a convenience sample of eligible patients (aged 18 years or older and diagnosed with hypertension) was enrolled during visits to one of five clinics in Japan from October 2012 to September 2014. We excluded patients who met any of the following criteria: already diagnosed with OSA, moderate or severe heart failure, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or dementia.

This study was approved by the ethics committee of Mito Kyodo General Hospital and was conducted according to the principles expressed in the Declaration of Helsinki. Study participants provided written informed consent.

2.1. Data collection

We used medical records to collect data on patients’ characteristics, which included age, gender, body mass index (BMI), office blood pressure, comorbidities (diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, ischemic heart disease, and cerebrovascular disease), number of antihypertensive drugs, current smoking status, regular alcohol use, and regular use of benzodiazepines. Physicians asked the patients who agreed to participate in the study if they have following six signs and symptoms: excessive daytime sleepiness; non‐restorative sleep; fatigue; insomnia; waking up with breath holding, gasping, or choking; and habitual snoring, breathing interruptions, or both noted by a bed partner or other observer. Subsequently, we assessed AHI and oxygen desaturation index (ODI) to obtain the frequency of respiratory events by using home sleep apnea testing (HSAT). We defined AHI as the average number of apneas and hypopneas per hour of sleep and ODI as the number of events per hour of recorded time in which blood oxygen saturation fell by ≥3%.

2.2. Statistical analysis

We diagnosed OSA according to ICSD‐2 criteria proposed by American Academy of Sleep Medicine.5 We classified AHI ≥ 22 on HSAT as moderate or severe OSA and 22 > AHI ≥ 5 as mild OSA based on a previous study.6 Differences in characteristics between patients who underwent home sleep apnea testing (HSAT) and those who did not were compared using Student's t test for continuous variables and Pearson's chi‐square test or Fisher's exact test for categorical variables. Subsequently, we developed a diagnostic algorithm using nine variables: age (≥50 years or <50 years), gender, BMI ≥ 27, office systolic blood pressure ≥140, office diastolic blood pressure ≥90, use of ≥3 antihypertensive drugs, current smoker, regular alcohol use, and regular use of benzodiazepines, for moderate or severe OSA using classification and regression tree analysis. P‐values were based on two‐sided tests and considered statistically significant at <0.05. General statistical analyses were performed with SPSS version 24.0‐J (SPSS‐Japan, Tokyo, Japan).

3. RESULTS

A total of 119 patients met the inclusion criteria, but 42 did not subsequently undergo HSAT and one had missing HSAT data. We developed the diagnostic algorithm based on data from 76 patients who underwent HSAT. Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. Forty‐nine patients (64.5%) had AHI ≥ 22, and 24 patients (31.6%) had 22 > AHI ≥ 5. Fifteen of 32 female patients (46.9%) and 13 of 28 postmenopausal female patients (46.4%) had AHI ≥ 22.

Table 1.

Characteristics of study patients

| All patients (n = 119) | % | Patients who underwent home sleep apnea testing (n = 77) | % | Patients who did not undergo home sleep apnea testing (n = 42) | % | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | |||||||

| Male | 73 | 61.3 | 45 | 58.4 | 28 | 66.7 | 0.434 |

| Female | 46 | 38.7 | 32 | 41.6 | 14 | 33.3 | |

| Mean age ± standard deviation (years) | 65.1 ± 11.7 | 63.6 ± 11.7 | 68.0 ± 11.1 | 0.045 | |||

| Age <50 years | 17 | 14.3 | 13 | 16.9 | 4 | 9.5 | 0.412 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | |||||||

| Mean ± standard deviation | 25.4 ± 3.5 | 25.3 ± 3.7 | 25.4 ± 3.1 | 0.868 | |||

| Range | 19.1‐38.8 | 19.8‐38.8 | 19.1‐33.7 | ||||

| ≥27 kg/m2 | 37 | 31.1 | 25 | 32.5 | 12 | 28.6 | 0.685 |

| Office systolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||||||

| Mean ± standard deviation | 140.7 ± 14.3 | 141.7 ± 13.3 | 138.8 ± 15.9 | 0.302 | |||

| ≥140 mm Hg | 67 | 56.3 | 47 | 61.0 | 20 | 47.6 | 0.179 |

| Office diastolic blood pressure (mm Hg) | |||||||

| Mean ± standard deviation | 82.9 ± 11.4 | 83.3 ± 10.7 | 82.0 ± 12.8 | 0.559 | |||

| ≥90 mm Hg | 34 | 28.6 | 20 | 26.0 | 14 | 33.3 | 0.525 |

| Antihypertensive drug | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.8 | 2.0 ± 0.9 | 0.557 | |||

| ≥3 antihypertensive drugs | 24 | 20.2 | 15 | 19.5 | 9 | 21.4 | 0.814 |

| Current smoker | 17 | 14.3 | 12 | 15.6 | 5 | 11.9 | 0.785 |

| Regular alcohol use | 62 | 52.1 | 44 | 57.1 | 18 | 42.9 | 0.128 |

| Comorbidities | |||||||

| Ischemic heart disease | 4 | 3.4 | 3 | 3.9 | 1 | 2.4 | 1.00 |

| Cerebrovascular disease | 8 | 6.7 | 7 | 9.1 | 1 | 2.4 | 0.257 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 4 | 3.4 | 3 | 3.9 | 1 | 2.4 | 1.00 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 31 | 26.1 | 16 | 20.8 | 15 | 35.7 | 0.085 |

| Regular use of benzodiazepines | 22 | 18.5 | 12 | 15.6 | 10 | 23.8 | 0.325 |

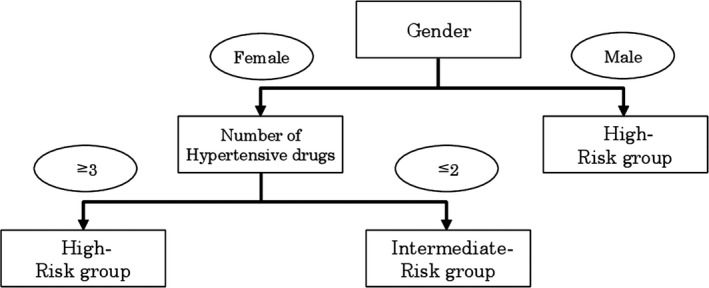

The classification and regression tree analysis generated two classification splits for the high‐risk groups (75% to <90% prevalence) and intermediate‐risk groups (<75% prevalence) for moderate or severe OSA (Figure 1). The high‐risk group included male patients, and female patients taking ≥3 antihypertensive drugs. Female patients not taking ≥3 antihypertensive drugs were placed in the intermediate‐risk group.

Figure 1.

The high‐risk group had a 75% to <90% prevalence of moderate or severe OSA, and the intermediate‐risk group had a < 75% prevalence of moderate or severe OSA

4. DISCUSSION

This is the first multicenter cross‐sectional study to explore the prevalence and characteristics of OSA and develop a diagnostic algorithm for unrecognized moderate or severe OSA among PC patients with hypertension.

The most important finding of this study was that 64.5% of patients had AHI ≥ 22, which fulfills the diagnostic criteria for moderate or severe OSA in patients with hypertension.7 This prevalence is much higher than in a recent study that estimated the prevalence of with hypertension to be 30%‐50%1, 4. One possible reason for the high prevalence of OSA in PC patients with hypertension is that we might have missed patients with hypertension who do not have obvious signs and symptoms of OSA in the PC setting until now. Thus, our results imply that many patients with hypertension in the PC setting need to be assessed for obstructive respiratory events during sleep.

The second important finding of this study was that we developed a diagnostic algorithm for unrecognized moderate or severe OSA. The diagnostic algorithm indicates that we should pay attention to detecting moderate or severe OSA in specific patients: male patients with hypertension, or female patients taking ≥3 antihypertensive drugs. This algorithm enables us to easily recognize the patients with hypertension who have a high risk of moderate or severe OSA, and accurately recommend HSAT for patients with hypertension in the PC setting.

Of note that our study revealed that female hypertension patients have high pretest possibility of moderate or severe OSA. This result implies that we should assess the obstructive respiratory events for female patients with hypertension as well as male patients.

The major limitations of this study were that we enrolled patients using convenience sampling, and the number of patients who did not undergo HSAT is large in comparison with those eligible in this study, though there was no significant difference except for mean age. And that this study had a small sample size despite being a multicenter study. Therefore, the validation is needed for clinical applications and caution is needed when interpreting the results.

5. CONCLUSION

The prevalence of OSA among PC patients with hypertension might be much higher than previously thought. In the PC setting, patients with hypertension who have specific risk factors for OSA should undergo assessment for obstructive respiratory events during sleep.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no relevant affiliations or financial involvement with any organization or entity with a financial interest in or financial conflict with the subject matter or materials discussed in the manuscript. This includes employment, consultancies, honoraria, stock ownership or options, expert testimony, grants or patents received or pending, or royalties.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The investigators and their participating institutions were Dr. Maki Nishimura, Dr. Miho Kiyota, Dr. Hiroki Ohashi, Dr. Morito Kise, and Dr. Nagaharu Kushige.

Hamano J, Tokuda Y. Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea in primary care patients with hypertension. J Gen Fam Med. 2019;20:39–42. 10.1002/jgf2.214

Funding information

This work was supported by the Japan Primary Care Association Research Fund (2012‐2013). All researchers were independent of the funder.

REFERENCES

- 1. Williams AJ, Houston D, Finberg S, Lam C, Kinney JL, Santiago S. Sleep apnea syndrome and essential hypertension. Am J Cardiol. 1985;55(8):1019–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Silverberg DS, Oksenberg A. Are sleep‐related breathing disorders important contributing factors to the production of essential hypertension? Curr Hypertens Rep. 2001;3(3):209–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, Abraham WT, Costa F, Culebras A, et al. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52(8):686–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Ahmad M, Makati D, Akbar S. Review of and updates on hypertension in obstructive sleep apnea. Int J Hypertens. 2017;2017:1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. American Academy of Sleep Medicine . International Classification of Sleep Disorders. Diagnostic and Coding Manual (ICSD‐2). 2nd ed. Westchester, IL, American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guerrero A, Embid C, Isetta V, Farre R, Duran‐Cantolla J, Parra O, et al. Management of sleep apnea without high pretest probability or with comorbidities by three nights of portable sleep monitoring. Sleep. 2014;37(8):1363–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. American Academy of Sleep Medicine . American Academy of Sleep Medicine. International Classification of Sleep Disorders. 3rd ed. Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2014. [Google Scholar]