The mitochondrial genome, which consists of 16,569 bp of DNA with a cytosine-rich light (L) strand and a heavy (H) strand, exists as a multicopy closed circular genome within the mitochondrial matrix. The machinery for replication of the mammalian mitochondrial genome is distinct from that for replication of the nuclear genome.

KEYWORDS: mtDNA, replication

ABSTRACT

The mitochondrial genome, which consists of 16,569 bp of DNA with a cytosine-rich light (L) strand and a heavy (H) strand, exists as a multicopy closed circular genome within the mitochondrial matrix. The machinery for replication of the mammalian mitochondrial genome is distinct from that for replication of the nuclear genome. Three models have been proposed for mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) replication, and one of the key differences among them is whether extensive single-stranded regions exist on the H strand. Here, three different methods that can detect single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) are utilized to identify the presence, location, and abundance of ssDNA on mtDNA. Importantly, none of these newly described methods involve the complication of prior mtDNA fractionation. The H strand was found to have extensive single-stranded regions with a profile consistent with the strand displacement model of mtDNA replication, whereas single strandedness was predominantly absent on the L strand. These findings are consistent with the in vivo occupancy of mitochondrial single-stranded DNA binding protein reported previously and provide strong new qualitative and quantitative evidence for the asymmetric strand displacement model of mtDNA replication.

INTRODUCTION

The mitochondrial genome consists of 16,569 bp of DNA with a cytosine-rich light (L) strand and a heavy (H) strand as a closed circle. The replication of the mammalian mitochondrial genome has been an area of extensive study, but with somewhat discordant results for competing models. There are three models, (i) asymmetric strand displacement, (ii) strand-coupled bidirectional replication, and (iii) alternative strand-coupled bidirectional replication, that have been described for mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) replication (reviewed in references 1, to ,7). The asymmetric strand displacement model proposes that L-strand synthesis does not initiate until the newly synthesized H strand is nearly 70% complete and passes the L-strand replication origin (OriL) between nucleotides (nt) 5721 and 5798. The strand-coupled bidirectional replication model suggests that bidirectional replication initiates around the H-strand replication origin (OriH) and the two forks progress around the mtDNA circle simultaneously. The alternative strand-coupled model (RITOLS) proposes that RNA is incorporated throughout the lagging strand at the same time that the H-strand synthesis is in progress, and the RNA is converted later to DNA. While the three models agree on the leading-strand (newly synthesized H strand templated from the L strand) replication, they differ greatly on how and when the new L strand is replicated. Although some features of each model of mtDNA replication are supported by various experiments, it remains controversial whether experimental artifacts may lead to confusion and disagreement.

One of the key differences between the two strand-coupled models and the asymmetric strand displacement model is that the asymmetric replication of mtDNA would result in extensive single-stranded regions on the H strand. There should not be much, if any, single strandedness on the H strand if mtDNA replicates in accord with the other two models. RNase H, which attacks RNA when it is paired with DNA, can expose single strandedness of the H strand if RITOLS plays a role in mtDNA replication. Methods that can detect single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) can be utilized to identify whether and where ssDNA is present on mtDNA and whether long RNA is involved in mtDNA replication when combined with RNase H treatment. Sodium bisulfite treatment of DNA followed by alkali can convert cytosine (C) to thymine (T) in the sequencing reads when the DNA is single stranded but not when the DNA is double stranded (for a review, see reference 8). Thus, subjecting DNA to sodium bisulfite treatment under native conditions allows the identification of single-stranded regions on each strand of the DNA of interest by sequencing after the treatment (9–11). Probing a slot blot of mtDNA in the native or denatured state using strand-specific probes can also detect the locations and quantitate the fraction of the DNA molecules with single-stranded regions.

In this study, in addition to using the two established methods mentioned above to detect single-stranded mtDNA, I developed a novel and sensitive oligonucleotide ligation assay to quantitate the fraction of molecules that harbor the single-stranded DNA in multiple regions on each strand of the mtDNA. Using this assay, I was able to compare replicating versus nonreplicating mitochondrial DNA and provide strong and clear evidence for the asymmetric strand displacement model of mtDNA replication.

RESULTS

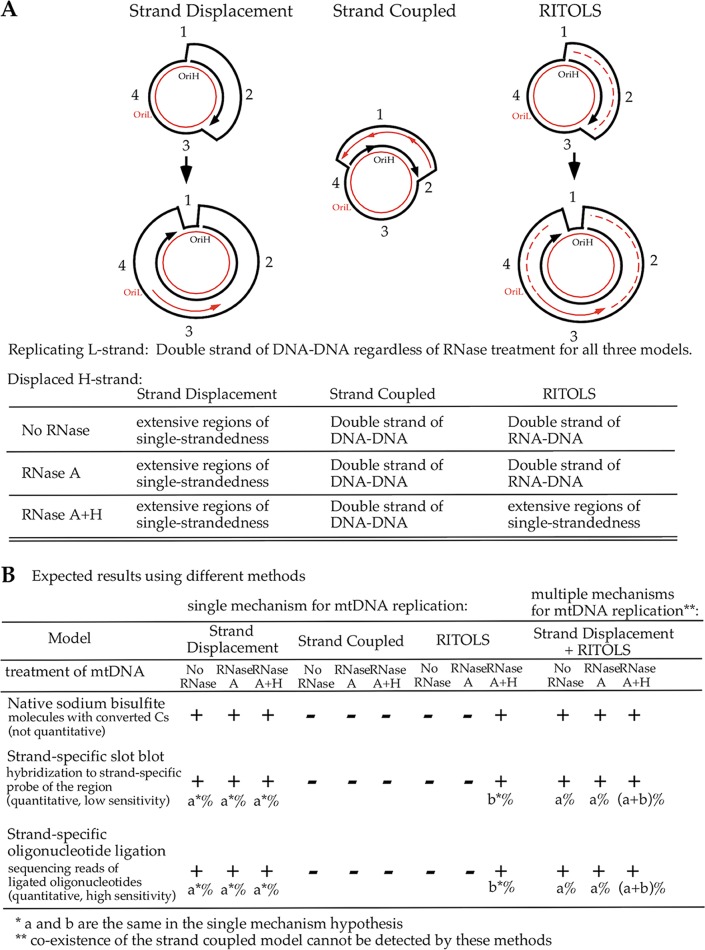

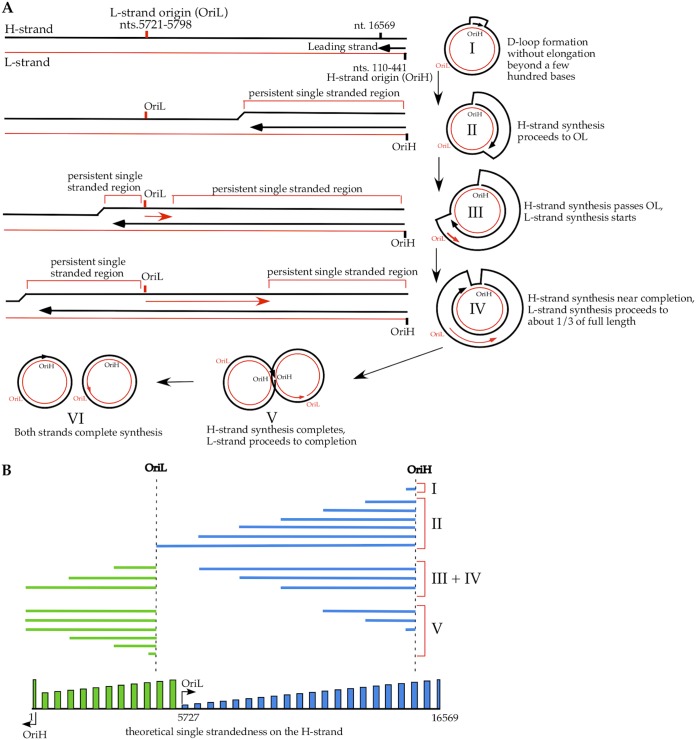

Theoretical replication intermediates based on the three mtDNA replication models.

The three models of mtDNA replication proposed previously predict different replication intermediates, as illustrated and summarized in Fig. 1A. All three models agree that the L strand is mostly, if not entirely, double stranded by pairing with the nascent H strand during mtDNA replication. The H strand would be single stranded in extensive regions in the strand displacement model, and the model predicts that as the H strand is being displaced by the leading strand (nascent H strand), single strandedness of the H strand progresses in the same direction as the leading-strand synthesis. This single strandedness would not be affected by any RNase treatment. However, the H strand would be mostly double stranded by pairing with RNA in the RITOLS model and by pairing with the nascent L strand of DNA in the strand-coupled model. No single-stranded region should exist based on the strand-coupled model, and RNase H, which removes RNA that pairs with DNA, would expose only very short regions of the DNA when the RNA primers that initiate DNA replication were removed. The RITOLS model proposed that the displaced H strand is paired with RNA that is 200 to 600 bases long either from newly synthesized long RNA primers or from preformed transcripts (for reviews, see references 4 and 5). The RITOLS model would suggest that single strandedness of the H strand can be detected only with RNase H treatment that digests the ribonucleotide-rich lagging strand (nascent L strand). Methods used in this study that detect single-stranded DNA in a strand-specific manner could potentially distinguish these three models for mtDNA replication (Fig. 1B). If no single-stranded region could be detected on the H strand regardless of RNase treatment, it would rule out the strand displacement model. If a single-stranded H strand could be detected only after RNase H treatment of mtDNA, it would suggest that RITOLS is one of the mechanisms for mtDNA replication. However, if extensive replication-dependent single strandedness could be detected on the H strand without any RNase treatment of mtDNA, it would support the strand displacement model. If there was increased single strandedness on the H strand after RNase H treatment of mtDNA, it would suggest that RITOLS is an additional mechanism of mtDNA replication. While the strand-coupled model cannot be entirely ruled out, a lack of single strandedness on the H strand regardless of RNase treatment would support a conclusion that the strand-coupled model is the only mechanism for mtDNA replication.

FIG 1.

Models of mtDNA replication and predicted experimental results. (A) Replication intermediates proposed by the three models and expected DNA conformations with different treatments of mtDNA. The red lines represent the L strand, and the black lines represent the H strand. The direction of the new DNA synthesis is indicated by an arrow. The solid lines represent DNA, and the dashed lines represent RNA. The “1” outside the circles indicates the beginning of new H-strand replication, and the increasing numbers indicate the direction of progression of the nascent H strand. (B) Expected observations in the three different assays used, with different treatments of mtDNA, if a single mechanism of replication is operating and if multiple mechanisms coexist, based on the three models. The readout of the assay is indicated under the name of each assay in the left column. “+” indicates a positive finding and “−” indicates a negative finding expected in the assay listed in the left column when mtDNA is treated in the manner indicated and the specific mtDNA replication mechanism listed at the top is operating.

Native sodium bisulfite sequencing assay detects single strandedness in limited regions of the mtDNA L strand.

Sodium bisulfite converts unpaired cytosine to uracil and can be used to determine whether unpaired DNA is present in otherwise double-stranded DNA molecules. The C’s in the duplex nucleic acid configuration are resistant to sodium bisulfite conversion from C to U; therefore, they remain as C in the subsequent sequence analysis. C’s in regions of single-stranded nucleic acid are subject to C conversion to U, and they are read as T in the subsequent sequencing analysis (9–11). When duplex DNA is treated with sodium bisulfite under native conditions, the single-stranded regions of the DNA can be distinguished from the duplex regions. There is a very low level of random and isolated conversion of C’s, likely due to random transient breathing of the two strands, and this establishes a low background level of C-to-T conversion. Single strandedness is indicated when extensive conversion of nearly all the C’s in a contiguous region is found in the molecule sequenced. A double-stranded state is indicated when no or only background sporadic conversion of the C’s is found in the molecule sequenced. Commonly, PCR primers without any converted bases are used to amplify DNA regions of interest after native sodium bisulfite treatment. Using this approach, the low background sporadic conversion permits one to determine from which strand the sequenced molecule is derived. It is worth noting that converted and unconverted molecules may not be amplified equally if there are any C’s in the primer priming region.

To eliminate potential bias against molecules with C conversions from amplification, I designed PCR primers with no C’s in their sequences in each strand, and they amplify molecules with and without C conversions from one strand, as well as molecules with no conversion in the priming region from the other strand. The L strand of mtDNA is very C rich (5,181 C’s in 16,569 nucleotides); therefore, only two limited regions (nt 1788 to 1987 and nt 2138 to 2473) can possibly have primers without C’s. With the sporadic conversion of C’s and the sporadically methylated cytosine at Alu restriction sites in mtDNA from 293/EBNA1+AluIMG cells, molecules that are PCR duplicates and the strand origin of the molecules can be discerned in most of the molecules sequenced. PCR product molecules with identical sequences were considered PCR duplicates and were counted as only one in the description below, Fig. 2, and corresponding tables in supplemental material. All molecules with no converted C’s (and therefore not distinguishable as to which DNA strand the molecule originated from) were counted, even though they were identical in sequence.

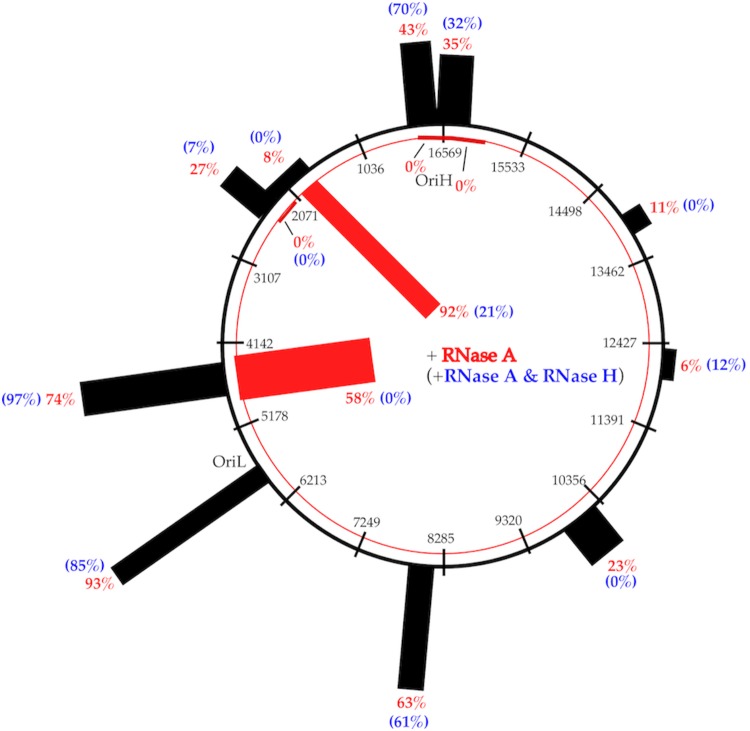

FIG 2.

Summary of native sodium bisulfite sequencing assay. The red circle represents the L strand, and the black circle represents the H strand, with the nucleotide numbering indicated at each line across both circles. The approximate locations of OriH and OriL are indicated. The fraction of molecules with extensive C conversion with RNase A treatment (red number) at each location examined is represented by the histogram in red on the inside of the circle for the L strand and by the histogram in black on the outside of the circle for the H strand. The blue number in parentheses indicates the fraction of molecules with extensive C conversions at each location when mtDNA was treated with RNase A and RNase H. The width of the histogram corresponds to the size of the PCR amplicon at each location.

Detection of molecules with extensive C conversions is summarized in Fig. 2, and the details are provided in the supplemental material, as indicated below. A large fraction (92%) of molecules sequenced from the nt 1788-to-1987 region of the L strand have extensive conversion of the C’s, indicating single-stranded features (see Table S5 in the supplemental material). In contrast, among 46 molecules examined from the nt 2138-to-2473 region, regardless of the strand of origin, none has extensive conversion of the C’s (see Table S5). While this assay is not considered quantitative, the proportion of molecules with substantial single-stranded zones suggests that the L strand is single stranded in the nt 1788-to-1988 region, at least on some mtDNA molecules, and that the L strand is likely to be double stranded on all or most of the molecules in the nt 2138-to-2473 region.

To further explore other regions of the L strand that might have single strandedness, primers with a minimal number of C’s on the L strand were designed for three other regions, specifically, nt 4285 to 4789, nt 16017 to 16490, and nt 16468 to 222 (through nt 1, as mtDNA is a circle) of mtDNA. Sodium bisulfite-treated DNA under native conditions from these three regions was amplified using primers of original mtDNA sequences (unmodified primers) with up to 3 C’s in the L strand. These primers amplify both strands if C’s in the priming regions remain unconverted, regardless of whether the internal C’s are converted. None of the molecules sequenced from the nt 4285-to-4789 and nt 16017-to-16490 regions showed any extensive conversion of C’s, regardless of the strand origin of the molecules (see Table S6 in the supplemental material). Of 57 molecules analyzed from the nt 16468-to-222 region, in a part of the D-loop, a single molecule among the 14 molecules from the H strand sequenced showed extensive conversion of C’s, while none of the 16 molecules from the L strand had extensive conversion of C’s (see Table S6). This indicates that some single strandedness exists in this region on the H strand, while no single strandedness was detected on the L strand. These findings are not entirely surprising, because the presence of C’s in the primers can bias against molecules with converted C’s in the priming regions, even though the reannealing temperature in the PCR was lowered to allow potential mismatches.

To include molecules with C conversions in the priming regions of the L strand that may be biased against using unmodified primers in the nt 4285-to-4789 and nt 16017-to-16490 regions, modified primers were used for amplification to enrich those molecules. All except one C in the forward primer for the nt 4285-to-4789 region of the L strand were changed to T’s for PCR amplification. These modified primers preferentially amplify molecules with C conversions in priming regions of the L strand and enrich molecules with C conversions at the priming sites. More than half of the 19 molecules from the L strand sequenced showed extensive conversion of C’s in the nt 4285-to-4789 region (see Table S7 in the supplemental material). None of the 32 molecules examined from nt 16017 to 16490 had any extensive conversion of C’s (see Table S7). These findings suggest that the single-stranded region is likely to include the priming regions in nt 4285 to 4789.

These findings, taken together with the results using unmodified primers described above, suggest that the nt 16017-to-16490 and nt 16468-to-222 regions of the L strand are most likely in the duplex DNA state. Some mtDNA molecules may have single strandedness in the H strand in the nt 16468-to-222 region, since a single H strand molecule with extensive C conversions was detected. With the enrichment of molecules with C conversions in the priming regions, it is quite clear that the L strand is single stranded on a subset of molecules in the nt 4285-to-4789 region.

Some replication-independent single strandedness of the L strand may be due to local RNA-DNA hybrids on the H strand.

It is curious that the nt 1788-to-1987 region showed single strandedness while the nt 2138-to-2473 region, which is less than 200 nucleotides from the nt 1788-to-1987 region, had no indication of this feature. This finding suggests that the single strandedness on the L strand is not continuous through these two regions and is not replication dependent. It has been accepted that the leading strand templated from the L strand is synthesized continuously if it is extended from the 7S DNA. Thus, the L strand should not be predominantly single stranded. However, it is possible that some local RNA-DNA hybrid formation on the H strand causes the L strand to be single stranded in some regions and not in others, independent of DNA replication (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). The other possibility is that the H strand acquires a local secondary structure (e.g., G quadruplex) and leaves the L strand unpaired, also independent of DNA replication (see Fig. S2).

Elimination of the RNA in the RNA-DNA hybrid should restore the double-stranded pairing of these regions, if mtDNA is treated with both RNase A and RNase H (see Fig. S2). To examine this possibility, mtDNA was amplified and sequenced as described above, with RNase H treatment, in addition to RNase A, before the native sodium bisulfite treatment (Fig. 2; see Table S8 in the supplemental material). After RNase H treatment, the fraction of molecules with extensive C conversions decreased from 92% (22 of 24 molecules sequenced) to 21% (3 of 14 molecules sequenced) in the nt 1787-to-1988 region. Similarly, molecules with extensive conversion of C’s decreased from 58% (11 of 19 molecules sequenced) to 0% (0 of 15 molecules sequenced) in the nt 4285-to-4789 region (PCR with modified primers) with RNase H treatment. No molecule with extensive C conversions was detected in the nt 2138-to-2473 region with RNase H treatment. Despite being a nonquantitative assay, the dramatic change in the number of molecules with single strandedness detected suggests the possibility that RNA-DNA hybrid formation on the H strand leaves the L strand unpaired in the nt 1787-to-1988 and nt 4285-to-4789 regions, at least on some of the molecules, independent of mtDNA replication. RNase H treatment allows the two DNA strands to pair and restore the DNA duplex state; therefore, the detection of single strandedness decreases dramatically. The detection of a relatively large fraction (21%) of molecules with extensive C conversions in the nt 1787-to-1988 region of the L strand despite RNase H treatment suggests that RNA-DNA hybrid formation is not the only basis for single strandedness in this region (secondary structure on the H strand may explain the remaining ones).

Single strandedness is detected in many regions of the H strand independent of RNase H treatment.

The H strand of mtDNA is the cytosine-poor strand, with only 2,169 C’s among the 16,569 nucleotides; therefore, it is relatively easy to find regions completely devoid of C’s to use as unbiased PCR primer regions for the strand. Ten different regions of mtDNA were sequenced using unmodified primers (with no C’s in the H strand) for PCR amplification after native sodium bisulfite treatment of DNA (Fig. 2; see Table S9 in the supplemental material). Molecules with extensive conversion of C’s on the H strand were detected in all 10 regions examined. The fraction of molecules showed that single strandedness ranged from 6% in the nt 12040-to-12360 region to 93% in the nt 5670-to-5903 region. While the assay is not quantitative, these findings clearly suggest that the H strand of mtDNA is likely to be single stranded in many regions.

To investigate whether the extensive single strandedness in the H strand is the consequence of replication-independent RNA-DNA hybrid formation in the L strand, DNA was treated with RNase A and RNase H before native sodium bisulfite sequencing (Fig. 2; see Table S10 in the supplemental material). With RNase H treatment, the single strandedness of the H strand should decrease if the H strand is displaced by replication-independent RNA-DNA hybrid formation on the L strand. However, the single strandedness of the H strand should increase globally with RNase H treatment if there is an appreciable fraction of the mtDNA molecules harboring replication-dependent RNA-DNA hybrids, which are continuous in long stretches, on the H strand. Three of the 10 regions examined, nt 10 to 303, nt 4379 to 4743, and nt 12030 to 12368, showed increases in single strandedness, while the other 7 showed decreases or no change in single strandedness. The limited regions showing a decrease in the number of molecules with single strandedness on the H strand with RNase H treatment indicate that single strandedness detected on the H strand is most likely due to the displacement of the strand during replication, with the L strand being paired with DNA, and not a replication-independent phenomenon.

Strand-specific slot blot hybridization assay detects single strandedness on mtDNA.

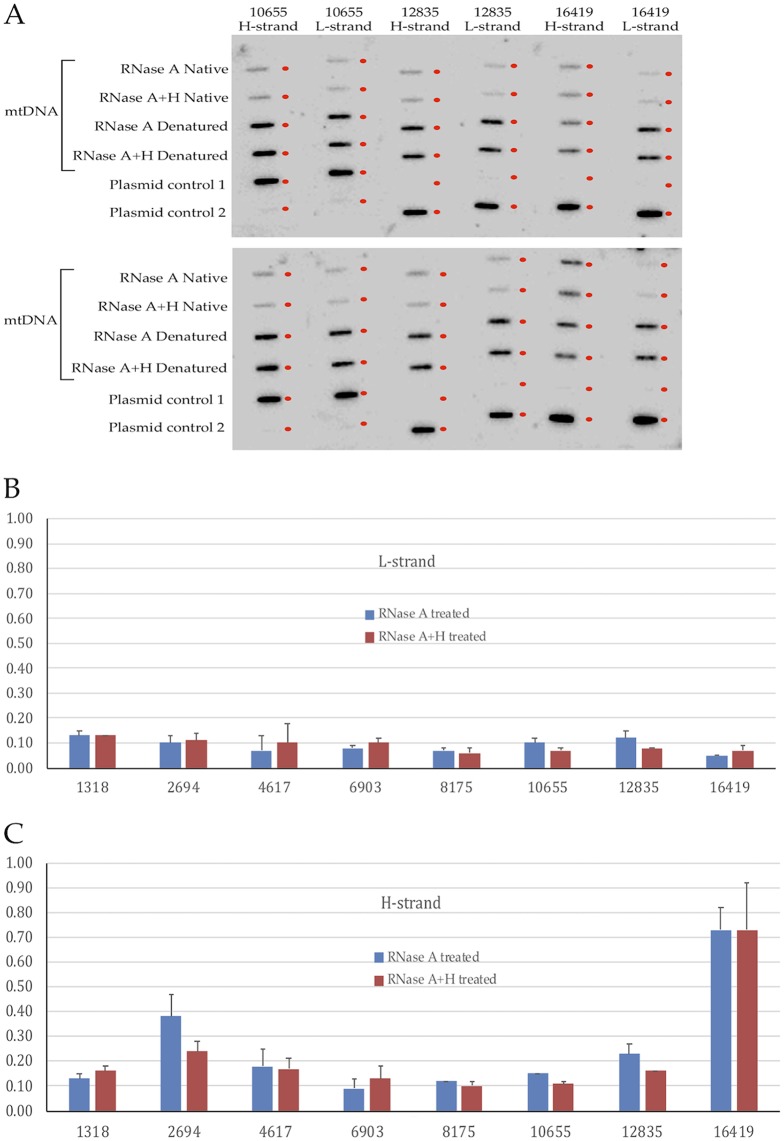

Native sodium bisulfite sequencing does not provide quantitative analysis of the fraction of mtDNA molecules having single strandedness at each specific location. I reasoned that hybridizing radiolabeled strand-specific oligonucleotides to immobilized denatured and undenatured (native) mtDNA on a slot blot might allow the quantitative analysis of molecules with single strandedness in zones where the oligonucleotide is complementary to the sequence. Denatured mtDNA should hybridize to the labeled oligonucleotide that represents an estimate of the total mtDNA in the slot. Undenatured mtDNA in its native state hybridizes to the labeled oligonucleotide only when the strand with complementary sequence is single stranded. By dividing the radioactivity detected in the slot with undenatured (native) mtDNA by the radioactivity detected in the slot with denatured mtDNA after background subtraction using a strand-specific oligonucleotide, the fraction of the particular strand with single strandedness at the specific location can be determined. In several pilot experiments, BamHI-digested and RNase A-treated mtDNA showed results of single strandedness similar to those for mtDNA without any restriction enzyme digestion and RNase treatment (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material), as well as BamHI-digested mtDNA without RNase treatment (data not shown). In those experiments, the DNA without RNase treatment consistently showed lower hybridization in both native and denatured configurations, even though the ratio of the two gave rise to the same conclusion for single strandedness. Therefore, mtDNA without RNase A treatment was not included in any further experiments. An image of 12 slot blots (duplicate experiments) hybridized to six different oligonucleotides at three locations is shown in Fig. 3A.

FIG 3.

Strand-specific slot blot hybridization assay. (A) Slot blot images of three probes hybridizing to the H strand and three probes hybridizing to the L strand, with the nucleotide numbers of mtDNA matching the first base of the probe sequence indicated. The DNA sample in each slot is indicated on the left of the blots. The position of each slot on the blot is marked by the small dot to the right of the slot. Two independent preparations of slot blots and probe hybridizations are shown. (B) Quantitation of radioactivity in the L strand of native mtDNA compared with that of denatured mtDNA or corresponding treatment as percentages on the y axis. Treatment with RNase A or both RNase A and RNase H (RNase A+H) is indicated. (C) Quantitation of radioactivity in the H strand of native mtDNA compared with that of denatured mtDNA or corresponding treatment as percentages on the y axis. Treatment with RNase A or both RNase A and RNase H is indicated. The error bars represent standard deviations.

Averaging from multiple replicates of the slot blot assay, 5% to 13% of the radioactivity was detected on the L strand in the undenatured mtDNA molecules compared with the total mtDNA molecules when the linearized mtDNA was treated with RNase A only (Fig. 3B). The fraction of molecules in single-stranded form was larger for the H strand, ranging from 9% to 73%, with the largest fraction in the nt 16401 region (Fig. 3C). Similar results were found in experiments of linearized mtDNA with RNase A and RNase H treatment (Fig. 3B and C). These findings suggest that the H strand is more often in single-stranded configuration than the L strand, especially in the nt 16401 region within the D-loop. Furthermore, RNA-DNA hybrid formation does not appear to cause single strandedness of either strand, since RNase H treatment led to very little or no change in the fraction of molecules with single strandedness in any of the eight regions examined.

Strand-specific oligonucleotide ligation assay detects single strandedness in the D-loop region on the H strand of the mtDNA from human platelets.

Strand-specific slot blot hybridization is very labor-intensive for examination of many regions, and the sensitivity is somewhat limited. An oligonucleotide ligation assay was developed, as described in Materials and Methods and illustrated in Fig. S1 in the supplemental material. This assay quantitates the fractions of mtDNA molecules that are single stranded at a large number of specific locations in a strand-specific manner with high sensitivity. The experiments are designed to detect single-stranded mtDNA at 24 locations 44 nucleotides in length on each strand, as described above (see Materials and Methods; see Table S3 in the supplemental material). All of the mtDNA samples were studied with three different treatments: (i) linearization by BamHI restriction enzyme, (ii) linearization by BamHI with RNase A present in the reaction, and (iii) further RNase H treatment after BamHI digestion and RNase A treatment. A total of 32 oligonucleotide ligation experiments were carried out for each mtDNA sample, with three different treatments (32 experiments for linearized DNA, 32 experiments for linearized and RNase A-treated DNA, and 32 experiments for linearized RNase A- and RNase H-treated DNA). The ligated oligonucleotides were PCR amplified with unique index combinations for each experiment and then deep sequenced. The sequencing read counts at each of the 24 locations in each of the 32 experiments (more than 400,000 reads per experiment and more than 16 million total reads per sample treatment) were used to derive the hybridization efficiency and the fraction of molecules that were single stranded in each of these locations. The sequencing read counts from mtDNA with denaturation prior to the oligonucleotide hybridization step were used for the total molecule quantitation. The sequencing read counts from DNA without denaturation prior to the oligonucleotide hybridization step were compared with the total molecule quantitation to derive the fraction of molecules with single strandedness at each location (described in Materials and Methods).

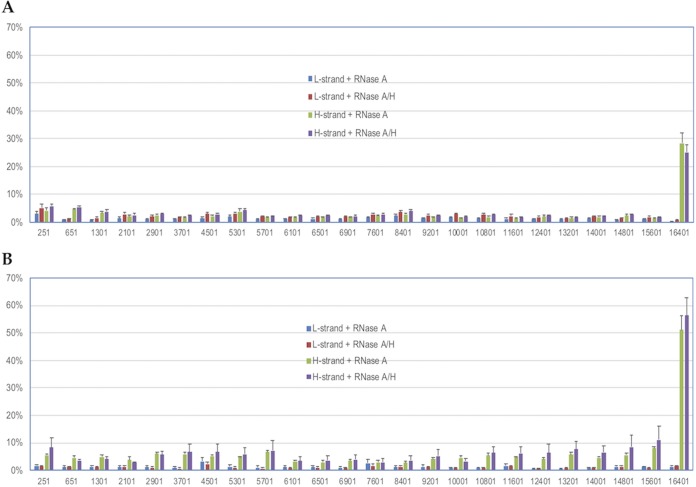

Platelets contain a small number of mitochondria that are fully functional for energy generation, redox signaling, and initiating apoptosis (12). It has been shown that there is no new mtDNA synthesis in human platelets (13–15). Therefore, mtDNA from human platelets was used to determine whether there are single-stranded regions at 24 different locations in mtDNA as a background control in the absence of mtDNA replication using the oligonucleotide ligation assay. Platelets from three unrelated individuals were used to ensure reproducibility and to identify any potential variations among different individuals. Low levels, 0.2% to 3.0%, of single-stranded molecules were detected in the 24 locations on the L strand of the mtDNA isolated from platelets from three different individuals treated with RNase A (Fig. 4A). Similarly small fractions of molecules with single strandedness were found on the L strand at all 24 locations when the mtDNA from platelets was treated with both RNase A and RNase H compared to mtDNA treated with only RNase A (Fig. 4A).

FIG 4.

Detection of single strandedness on mtDNA molecules using the strand-specific oligonucleotide ligation assay. (A) Single strandedness observed in the D-loop of the H strand from human platelets. (B) Single strandedness in many regions of the H strand detected from actively dividing human cells. The y axis shows the percentage of single strandedness in the total mtDNA detected at each location. The percentage of mtDNA molecules with single strandedness in the native state (y axis) detected from each region was calculated after normalization of the assay efficiency and then divided by the total number of molecules detected under denaturing conditions. The numbers on the x axis indicate the nucleotide positions of the first base of oligonucleotide 1 on the 5′ end for the 24 regions examined. The x axis is not labeled proportionally to the actual length of the mtDNA molecule. Each bar in the histogram is the average of three samples, with eight experiments for each sample (24 experiments in total), and the error bars indicate the standard deviations. The identities of the strands examined and the treatments are indicated.

Low levels, 0.9% to 4.6%, of single-stranded molecules were detected in 23 of the 24 locations on the H strand of the mtDNA isolated from platelets from three different individuals when it was treated with RNase A or treated with RNase A and RNase H. Nearly 30% of the mtDNA molecules showed single strandedness in the nt 16401 region of the H strand (Fig. 4A). Very little difference in the fraction of single-stranded molecules was detected in the H strand of the mtDNA treated with both RNase A and RNase H compared with mtDNA treated with RNase A alone (Fig. 4A). The mtDNA without any RNase treatment showed results similar to those of the experiments with RNase treatments; however, the single strandedness was approximately 5% higher without any RNase treatment in regions 251 and 16401 than in experiments with any RNase treatment (see Fig. S4 and the text in the supplemental material).

The observations here, based on more than 150 million reads from nine mtDNA samples (a total of 288 experiments; platelets from three individuals with three different treatments), were consistent and reproducible among multiple experiments, four for the L strand and four for the H strand, within the same individual and across three different individuals. These findings clearly indicate that the H strand of the mtDNA is single stranded in the nt 16401 region on a large fraction of the molecules and that very little variation of the single strandedness exists among different individuals in the absence of mtDNA replication. Also, an RNA-DNA hybrid is not likely to be present in the nt 16401 region on the H strand, because RNase H digestion did not lead to any increase in single strandedness.

Single strandedness is detected throughout the H strand of mtDNA harvested from actively dividing human cells.

Nucleotide 16401 in the D-loop region is the only region where single strandedness is detected on the H strand in a high proportion, nearly 30%, of the mtDNA from human platelets (which lack DNA replication). To examine whether mtDNA replication changes the location and level of the single strandedness on mtDNA, I carried out an oligonucleotide ligation assay using mtDNA extracted from actively dividing human cells. Each set of 32 experiments described in Table S4 in the supplemental material was carried out using three independent harvests of mtDNA from 293/EBNA1 cells. More than 150 million total reads from nine mtDNA samples (three mtDNA harvests and three different treatments) were analyzed.

Similar to what was found in platelets, low levels (0.2% to 5.2%) of the mtDNA molecules had single strandedness in all 24 locations on the L strand in all three treatments of mtDNA from 293/EBNA1 cells harvested at three different times (Fig. 4B; see Fig. S4). Larger fractions of single-stranded molecules were detected on the H strand (0.6% to 38% for BamHI digestion only; 2.8% to 51.1% for RNase A-treated DNA; 2.8% to 56.4% for RNase A- and RNase H-treated DNA) than on the L strand (Fig. 4B; see Fig. S4). These findings strongly suggest that a larger fraction, as well as a greater number of regions, of the mtDNA molecules have single strandedness on the H strand in 293/EBNA1 cells than in platelets, while the L strands are similar in the two sources. A few regions showed a higher level of single strandedness on the H strand in mtDNA without any RNase treatment, likely due to RNA interfering with oligonucleotide hybridization (see Fig. S4 and the text in the supplemental material). The fact that there was no increase in single strandedness with RNase H treatment indicates an absence of RNA pairing with the H strand during mtDNA replication.

Replication-dependent changes in single strandedness of the mtDNA are strand biased and nonuniform in actively dividing human cells.

The difference observed in single strandedness on mtDNA from platelets and from actively dividing cells was most likely caused by DNA replication, since RNase A and RNase H treatments would eliminate single strandedness attributable to RNA (little difference with RNase H treatment was observed). To determine the impact of DNA replication on single strandedness of mtDNA, the average fraction of mtDNA molecules with single strandedness detected in three platelet samples (without mtDNA replication) in each of the 24 regions studied can be used as the background level. The change in the fraction of single-stranded molecules for each region with mtDNA replication can be determined by subtracting this background level from the average fraction of mtDNA molecules with single strandedness in three independent harvests of 293/EBNA1 cells in each region of the mtDNA examined. These changes reflect the change in single strandedness on each strand of mtDNA associated with DNA replication, since the RNase A and RNase H treatments eliminate transcript-dependent changes. While the results from BamHI digestion without any RNase treatment were similar to the experiments with RNase treatments, the presence of RNA in the hybridization reaction mixture appeared to interfere with the reaction in a regionally specific manner (see Fig. S2 and the text in the supplemental material). Therefore, only samples treated with RNase A and treated with RNase A and RNase H were included in this analysis to avoid artifacts caused by the presence of free RNA.

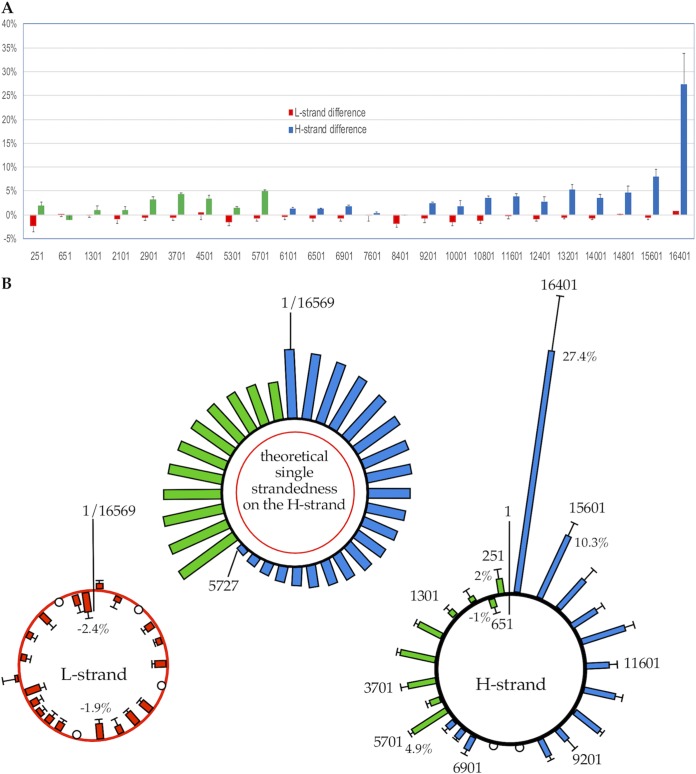

One of the major differences that distinguishes the three proposed models for mtDNA replication is that the H strand is single stranded for a substantial amount of time during replication (Fig. 1 and 5). The asymmetric strand displacement model proposed that replication begins with synthesis of the new H strand (leading strand) from OriH, while the parental H strand is displaced by the nascent H strand (Fig. 5A). The parental H strand becomes single stranded from OriH toward OriL in the same direction as the leading-strand synthesis due to this displacement. When OriL is exposed and new L strand (lagging-strand) synthesis in the opposite direction starts, the size of the single-stranded region on the parental H strand decreases in the same direction as the L strand synthesis. At the same time, the parental H strand upstream of the OriL become single stranded, as the leading-strand synthesis proceeds past the OriL. Assuming that the rates of DNA synthesis are the same for new H strand and L strand syntheses, the length of time that the H strand stays single stranded would have two peaks, one near OriH and one near OriL (see Fig. 5B for an illustration of the theoretical single strandedness on the H strand).

FIG 5.

Presence of single-stranded DNA on mtDNA during replication based on the asymmetric strand displacement model. (A) Illustration of different stages of mtDNA replication and regions of single strandedness based on the model in both circular and linear forms. (B) (Top) Illustration on a linear mtDNA molecule of the theoretical relative amount and length of single-stranded DNA that should be detected on the H strand, based on the model, assuming equal rates of DNA synthesis for the two strands. There is no single strandedness on the L strand based on this model. (Bottom) Illustration on a circular mtDNA molecule of the same theoretical data shown in the top illustration (with the nt 5727 region as 1). The two peaks of increased single strandedness are marked by different colors, blue and green, as in the top illustration.

The L strand shows five regions with absolute differences of >1.0% decrease in single strandedness in mtDNA from 293/EBNA1 cells compared with the background level from human platelets (Fig. 6A shows a linear display; Fig. 6B shows a circular display). These small changes may be the natural fluctuation of the assay. It is also likely that the background level of single strandedness detected in the platelets is due to mtDNA degradation that occurs more in the platelets with increased time since their origination in the bone marrow. Therefore, the level of single strandedness on the L strand detected in the actively dividing cells, which do not have increased DNA degradation, may be expected to be lower than the background detected in the platelets. In contrast, the H strand showed >1% absolute differences in 21 regions, with the largest increase of 27.4% in the nt 16401 region (Fig. 6). The decrease in single strandedness in actively dividing cells observed on the L strand may also exist for the H strand, and the increase in single strandedness estimated here may be an underestimate. These findings strongly suggest that mtDNA replication leads to single strandedness on the H strand and not on the L strand.

FIG 6.

Change in single strandedness detected by strand-specific oligonucleotide ligation assay in actively dividing cells. (A) Change in the absolute percentage of mtDNA molecules that are single stranded in each of the 24 regions (y axis) in actively dividing human 293/EBNA1 cells as calculated by subtracting background detected in mtDNA from human platelets. Each histogram is the average change of three samples with two different treatments (RNase A and RNase A+H), and the error bars represent standard deviations. The numbers on the x axis indicate the nucleotide position of the first base of oligonucleotide 1 on the 5′ end for the 24 regions examined. The x axis is not proportional to the actual length of the mtDNA molecule. The identities of the strands examined and the treatments are indicated. (B) (Left) Illustration of changes of single strandedness on the L strand in actively dividing cells in each of the 24 regions on a circular molecule (using the same data as for panel A, red bars). (Center) The theoretical single strandedness on the H strand illustrated on a circular molecule (same as Fig. 5B, bottom). (Right) Change of single strandedness on the H strand in actively dividing cells in each of the 24 regions illustrated on a circular molecule (same data and colors as for panel A), with colors matching regions in the theoretical plot in the center and in Fig. 5B. Bars representing decreases in the actively dividing cells are inside the circle, and those representing increases are outside the circle. The open circles indicate no change of single strandedness.

The increase in single strandedness on the H strand detected in the oligonucleotide ligation assay was not uniform throughout the molecule. The greatest increase was detected in the nt 16401 region, which is in the D-loop. The single strandedness progressively decreases from the nt 16401 region (around OriH) toward the OriL (nt 5721 to 5798) in the same direction as the leading-strand synthesis from the L-strand template (Fig. 6, blue bars). A smaller peak of single strandedness starts just downstream of OriL and decreases toward the D-loop, also in the same direction as the leading-strand synthesis (Fig. 6, green bars). These trends are consistent with the theoretical prediction of strand bias for single strandedness on the H strand based on the asymmetric strand displacement model.

DISCUSSION

This study provides both qualitative and quantitative evidence, using novel assays, that the H strand of mtDNA has extensive single strandedness during mtDNA replication, while the L strand is occupied by the leading DNA strand. The length of time that the H strand remains single stranded is highly proportional to the progression of the new DNA strand synthesis. A large fraction of the mtDNA molecules harbor a D-loop mediated by a DNA strand hybridizing to the L strand in the absence of mtDNA replication. My findings show that RNA-DNA hybrid formation is not likely involved in mtDNA replication. However, RNA-DNA hybrids may be present focally on one of the strands, independent of DNA replication, along with other conceivable mechanisms (such as G-quadruplex formation) that displace the other strand in some regions and lead to single strandedness in such regions. Taken together, the findings in this study strongly favor the asymmetric strand displacement model for mtDNA replication over the RITOLS model. However, the coexistence of strand-coupled replication cannot be ruled out.

Native sodium bisulfite sequencing and strand-specific slot blot hybridization were used to detect the extent of single strandedness on each strand of mtDNA in actively dividing cells (293/EBNA1+AluIMG and 293/EBNA1). Interestingly, I detected single strandedness on the L strand in two out of five regions studied by the native sodium bisulfite sequencing assay. The detection of many fewer molecules harboring single-stranded regions on the L strand after RNase H treatment suggests that RNA-DNA hybrid formation on the H strand may be a replication-independent cause for single strandedness detected locally on the L strand (RNase H treatment eliminates the RNA-DNA hybrid involving the H strand, allowing the two strands to reanneal, and thereby reduces the single strandedness detected). The remaining molecules with single strandedness detected in the nt 1788-to-1987 region suggest a potential DNA structure, such as a G quadruplex, on the H strand that renders the L strand unpaired in this region. The slot blot hybridization showed a low level of single strandedness at all eight locations of the L strand examined, regardless of RNase H treatment. In contrast, the native sodium bisulfite sequencing method identified single strandedness in all 10 regions examined on the H strand, and RNase H treatment did not change that observation in 7 of the 10 regions. While the native sodium bisulfite sequencing method is not quantitative, RNase H treatment leads to decreases in the detection of single strandedness in most of the regions. Consistent with these findings, the slot blot hybridization assay showed a larger fraction of single strandedness on the H strand than the L strand in general, with regions around nt 2700 and nt 16401 being the highest, regardless of RNase H treatment. Taken together, the findings from these two assays demonstrate that there is little single strandedness on the L strand and a much larger amount of single strandedness on the H strand. In addition, mtDNA without any RNase treatment showed results similar to those for the RNase-treated mtDNA, indicating that single strandedness exists on untreated mtDNA. It is noteworthy that RNase H treatment leads to a dramatic reduction in the detection of molecules with single strandedness on the L strand, and this demonstrates the absence of any RNase H-like activity in the RNase A-treated reactions. These findings suggest that RNA is not likely to hybridize to the H strand, since RNase H treatment does not affect the experimental outcomes. The slot blot hybridization assay is the more quantitative but less sensitive method of the two assays, and it showed that 70% of the H strand is single stranded in the nt 16401 region, indicating the D-loop is present on a large fraction of the mtDNA molecules. This is consistent with previous observations by others (10% to 90% in different species and cell types [for a review, see reference 16]). Both assays suggest that the single strandedness is strand biased, the level is not uniform for the H strand throughout the molecule, the single strandedness of the H strand is readily detectable on the molecules free of RNase treatment, and RNA is in general not present on the H strand.

An oligonucleotide ligation method was developed as an independent and more sensitive quantitative assay for determining the frequency of single strandedness on each strand of mtDNA in cells. Using this assay, control experiments were first performed using mtDNA from platelets, which do not carry out mtDNA replication and thus should possess little single-stranded DNA. Consistent with this, only a low level of single strandedness was detected on both strands throughout the mtDNA molecule, with one exception. A large fraction, around 30%, of the H strand was single stranded in the nt 16401 region, which is in the D-loop. There was little difference detected with or without RNase H treatment. This finding is consistent with my findings using the native sodium bisulfite sequencing and slot blot hybridization assays and in agreement with previous reports that a DNA-mediated D-loop is commonly present in mtDNA (for a review, see reference 16). The presence of 7S DNA, about 650 bases from nt 191 (in OriH) to nt 16106 (in the termination-associated sequence [TAS]), leads to a three-stranded D-loop structure, leaving the H strand unpaired. It has been shown that the 7S DNA turns over very rapidly in rodent cells (17, 18), and nucleolytic activity is potentially responsible for its turnover. My finding suggests that the nucleolytic activity is likely lost in platelets, and 30% of the mtDNA molecules with single strandedness in the D-loop observed in this assay may reflect the fraction of mtDNA harboring 7S DNA at any given time without turnover or DNA replication.

There have been many studies on the replication of the mammalian mitochondrial genome, with somewhat discordant results that led to competing models and debates in the last few decades. A major difference between the asymmetric strand displacement model and the other two models (strand-coupled bidirectional replication and RITOLS) is that the H strand remained single stranded for a substantial amount of time during replication in the asymmetric strand displacement model and exhibited little or no extensive single strandedness in the other two models (Fig. 1). Using the quantitative strand-specific oligonucleotide ligation assay, the actively dividing human cells showed a strand-biased increase in single strandedness on the H strand that was not uniform throughout the molecule. In the D-loop region, about 56% of the mtDNA molecules were single stranded in actively dividing cells, in contrast to nearly 30% detected in platelets by the oligonucleotide ligation assay. It has been estimated that 25% of the 7S DNA serves as primers for continued replication in mouse cells (19). If this is also the case in human mtDNA, an estimated 14% (1/4 of 56%) of the mtDNA goes through full molecule replication in 293/EBNA1 cells. A level of single strandedness 8.3% higher than background (1.1%) detected in the nt 15601 region in actively dividing cells is consistent with this estimate, especially considering that the background level in platelets may be an overestimate. The results from the slot blot hybridization assay, which detected 73% single-stranded DNA in the nt 16401 region and approximately 20% single-stranded DNA in the nt 12800 region, are consistent with the findings from an oligonucleotide ligation assay. The two peaks of increased single strandedness around the nt 5701 and nt 15601 regions in the actively dividing cells and the trend of directionally progressive decrease in single strandedness are consistent with the theoretical prediction of strand bias for single strandedness on the H strand, based on the asymmetric strand displacement model (Fig. 5). Potentially, the synthesis of the L strand may be faster than that of the H strand because the parental H strand template is already single stranded and does not need to be unwound. If so, the percentage of single strandedness on the H strand would be lower in the regions away from OriL than the prediction, which is based on equal rates of synthesis of the two strands.

It has been shown that mitochondrial single-stranded DNA-binding protein (mtSSB) is recruited to Twinkle, the mtDNA helicase, and this occurs in a Twinkle-dependent manner during mtDNA replication (20). It has also been reported that mtSSB associates with the mtDNA H strand in a strand-biased manner with a major negative gradient from OriH to OriL in the same direction of leading-strand replication and a minor one from OriL toward OriH on the other side of the OriL (21). This strand-biased distribution of mtSSB may reflect a replication-dependent single-stranded feature, since mtSSB is actively recruited during mtDNA replication. My detection of two similar gradients of single strandedness on the H strand in actively dividing cells and not in platelets is consistent with the distribution of mtSSB on the H strand in strand-specific chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis (21). My study using an independent and quantitative method provides strong and consistent evidence supporting the asymmetric strand displacement model.

Since the first reports of replication intermediates and the proposed asymmetric strand displacement model of mtDNA (22, 23), various studies have demonstrated and characterized these intermediates (for reviews, see references 1 and 2). However, other studies suggest the involvement of RNA that occupies the H strand during mtDNA replication (24–27). If RNA-DNA hybrid formation throughout the H strand during replication, as proposed by the RITOLS model, is the sole mechanism for mtDNA replication, the H strand should be double stranded without RNase H treatment (no single strandedness on the H strand). If RITOLS and strand displacement are both occurring, an increase in single strandedness should be detected on the H strand when the DNA is treated with RNase H. The current study demonstrated that there is no detectable replication-dependent RNA-DNA hybrid formation on mtDNA, as reflected by the detection of single strandedness without any RNase treatment and the lack of change in single strandedness when DNA was treated with RNase H. It was previously suggested that RNase H as a cellular contaminant in mitochondrion harvest destroys the RNA-DNA hybrid on mtDNA molecules before DNA extraction is carried out, and it was suggested that this may be the cause of the failure to detect RNA-DNA hybrids in studies supporting the strand displacement model (26). No nuclease is known to survive the methods used for mtDNA extraction in the current study (1% SDS with high concentrations of proteinase K added immediately). Furthermore, the experiments without RNase treatment indicated that there was no RNase H-like activity present in the assays without added RNase H. Detection of RNA-DNA hybrids in the nuclear genome has been routinely done for more than a decade by myself and others (9–11), illustrating the lack of RNase H activity in the DNA harvests and the RNase A treatments of DNA. Otherwise, the RNA-DNA hybrids would not have been preserved in those experiments. The confidence level in concluding that single strandedness occurs in many regions of the H strand without any RNase H treatment is extremely high, based on my expertise in extracting and handling DNA without introducing RNase, the reproducibility of the assays, and the multiple methods used. It was also suggested that incubating purified mitochondrial RNA with crude rat liver mtDNA did not create RNA-DNA hybrids as an experimental artifact in 2-dimensional (2D) gel analysis, and this was interpreted as supporting the RITOLS model (26). The observation in the current study that RNA can interfere with oligonucleotide hybridization by annealing to denatured (single-stranded) mtDNA indicates that RNA-DNA hybrids may be created as artifacts under certain experimental conditions. The addition of mitochondrial RNA to mtDNA described by Yang et al. (26) should actually be done by adding the mitochondrial RNA to RNase A- and RNase H-treated mtDNA to eliminate any RNA-DNA hybrids that were present as a prior artifact. The mixing experiment described by Yang et al. (26) does not rule out the possibility that the RNA-DNA hybrids detected in that study and other similar studies are artifacts of free RNA reannealing to single-stranded regions of mtDNA.

Furthermore, similar to the study on mtSSB localization (21), the mtDNA extracted is likely to be total mtDNA in the source cell and not a particular form of mtDNA, which may have led to the controversial findings and different models for mtDNA replication in many previous studies. Global association of RNA with the H strand during DNA replication is highly unlikely, even though local association of RNA with DNA independent of mtDNA replication in some regions may lead to the detection of single strandedness in those regions (see Fig. S2). Although the experiments in the current study cannot rule out the strand-coupled model, it is clear that the strand-coupled model is not the sole mechanism for mtDNA replication if it exists. It is possible that RITOLS exists as an additional and minor mechanism of mtDNA replication under certain conditions in some cells, but much more evidence from rigorous experimentation would be required before potential artifacts could be definitively ruled out. In conclusion, this study rules out global RNA-DNA hybrid formation on the H strand during mtDNA replication, as proposed by the RITOLS model, and provides strong support and clear evidence for the asymmetric strand displacement model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell line and DNA extraction.

The 293/EBNA1 cell line, a derivative of the 293 human embryonic kidney carcinoma cell line (293HEK) described previously (28), was used for the slot blot hybridization assay and the oligonucleotide ligation assay. 293/EBNA1+AluIMG is a cell line derived from 293/EBNA1 cells by integrating a humanized Alu methylase expression vector in the cells. Cytosine at the Alu restriction sites on mtDNA was sporadically methylated in the 293/EBNA1+AluIMG cells. DNA from this cell line was used for the native sodium bisulfite sequencing to increase the capability to identify the DNA strand of origin. The cells were grown in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) with 10% fetal calf serum and penicillin-streptomycin. Genomic DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform after proteinase K treatment of the cells lysed in 1% SDS. The Hirt method (29), which also uses SDS lysis, proteinase K treatment, and phenol-chloroform extraction, was used to harvest mtDNA from 293/EBNA1 cells for slot blot assays and oligonucleotide ligation assays. Human platelets from apheresis (Memorial Blood Centers, St. Paul, MN) were used for mtDNA extraction by the same method as for genomic-DNA extraction described above after pelleting the platelets at 5,800 × g for 30 min. The extracted mtDNA from cultured cells and human platelets was analyzed on agarose gels both with and without restriction enzyme digestion to authenticate the mtDNA and assess its purity. RNase, DNase, and other enzymes are not known to survive DNA extraction methods using high-SDS lysis and proteinase K treatment, followed by phenol-chloroform extraction.

RNase A and RNase H treatments.

RNase A treatment of DNA was carried out in the indicated experiments to remove free RNA in 10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, 10 mM MgCl2, and 50 mM NaCl at a final concentration of 0.1 μl/μg RNase A at 37°C overnight, unless otherwise indicated, with or without a restriction enzyme. RNA-DNA hybrids generated from in vitro transcription have been tested and shown to withstand treatment with up to 1 μl/μg RNase A. In addition, detection of RNA-DNA hybrids in the nuclear genome was not affected after treatment with 0.4 μl/μg RNase A overnight (9–11). A final concentration of 1.5 ng/μg RNase H was added to remove the RNA in the RNA-DNA hybrids and incubated at 37°C overnight for the indicated experiments. The treated DNA was phenol-chloroform extracted and ethanol precipitated before being resuspended in TE (10 mM Tris, pH 8.0, and 1 mM EDTA).

Native sodium bisulfite sequencing.

Sodium bisulfite treatment of DNA was carried out without denaturing the DNA. Three micrograms of total genomic DNA or approximately 60 ng of mtDNA from Hirt harvest embedded in 28 μl of 1% agarose (agarose plug) was treated with 450 μg 5 M sodium bisulfite without heat denaturation for 5 h at 37°C. After the sodium bisulfite treatment, the DNA embedded in agarose was washed with water (4 times), alkaline treated (0.3 M NaOH; 4 times with 10-minute incubation the last time), washed with water (3 times), and equilibrated with TE. The agarose was melted at 70°C after the washing steps with an equal volume of TE added. PCR was carried out using 1 μl of the treated DNA and appropriate primers (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). The primers designated “top” targeted L strand amplification regardless of C conversions. Likewise, primers designated “bot” targeted H strand amplification regardless of C conversions. When the C’s in the priming regions of the other strand are not converted, the sequence of the other strand can also be amplified, in addition to the targeted strand. The PCR products were ligated into the TOPO TA cloning vector (Invitrogen), and multiple clones from each ligation were sequenced. Clones from at least two independent PCRs were sequenced to rule out any potential jackpot effect. Both strands of each clone were sequenced using an Excel II sequencing kit (Epicentre, Madison, WI) and analyzed on a model 4200 sequencer (Li-Cor, Lincoln, NE). Importantly, all the amplicons had multiple (2 to 72) mismatches with sequences in the nuclear genome that were evolutionarily reinserted from mtDNA (NUMT) or had no matching sequence in the nuclear genome. Therefore, sequences from the nuclear genome could be clearly identified, and all of the molecules sequenced were of mitochondrial origin.

Strand-specific slot blot assay.

Slot blots of mtDNA samples from 293/EBNA1 cells and plasmid DNA controls were made using a slot blot apparatus (Hoefer Scientific Instrument, Holliston, MA). All of the mtDNA from 293/EBNA1 cells was harvested by the Hirt method and linearized with BamHI restriction enzyme (unless otherwise indicated) and a final concentration of 0.1 μl/μg RNase A present (unless otherwise indicated) for 3 hours. Although BamHI may not digest some of the replication intermediates if the cut site is either a single-stranded or a double-stranded RNA-DNA duplex, it will digest all the molecules at least once to release any potential torsional stress on the molecules. A portion of the digested and RNase A-treated DNA was further treated with 1.5 ng/μg RNase H for 5 h or longer. mtDNA was phenol-chloroform extracted and ethanol precipitated after enzyme treatment, after which half of the DNA was further denatured and the other half was kept in its native state. Denaturation of mtDNA was done by boiling for 10 min in 20 mM Tris and 1 mM EDTA, followed by treatment with a final concentration of 0.5 mM NaOH for 10 min at room temperature, and then neutralized with an equal volume of neutralization solution (1.5 M NaCl, 1 M Tris, pH 7.5). The native mtDNA received no further treatment other than the neutralization solution that was added. The first four of the six slots of each blot contained the following: (i) mtDNA with RNase A treatment without denaturation, (ii) mtDNA with RNase A and RNase H treatment without denaturation, (iii) mtDNA with RNase A treatment with denaturation, and (iv) mtDNA with RNase A and RNase H treatment with denaturation. The remaining two slots on each blot contained plasmid DNA with different regions of mtDNA as positive and negative controls, corresponding to the oligonucleotide probes used for the specific slot blot. Strand-specific oligonucleotide probes for eight different locations of the mtDNA used for the slot blot hybridization are listed in Table S2 in the supplemental material. The probes were end labeled using T4 polynucleotide kinase and radioactive ATP. After overnight hybridization, the blots were washed and exposed to a phosphorimaging screen. The amount of radioactivity in each slot on the slot blots was quantitated using a Bio-Rad FX phosphorimager (Bio-Rad Laboratory, Hercules, CA). The fraction of the molecules with single-stranded features in the region of the probe was determined by dividing the radioactivity in the native mtDNA slot by the radioactivity in the corresponding denatured mtDNA slot after background subtraction.

Strand-specific oligonucleotide ligation assay.

The strand-specific oligonucleotide ligation assay is illustrated in Fig. S1. The strategy of this assay is to ligate two adaptor-tailed oligonucleotides, each of which has 22 nucleotides that match one half of a 44-base mtDNA sequence (Fig. 1A; see Table S3). When these two oligonucleotides hybridize to single-stranded mtDNA adjacent to each other, they can be ligated to become a molecule with 44 bases of mtDNA sequence flanked by a different adaptor on each end (see Fig. S1B). Twenty-four pairs of oligonucleotides were designed to hybridize to the L strand at 24 locations approximately 400 bases to 800 bases apart, and 24 pairs of oligonucleotides were designed to hybridize to the H strand at the corresponding locations of the mtDNA (see Table S3). The ligated oligonucleotides could be PCR amplified with index primers, one with i5 index and the other with i7 index (dual-indexed sequencing for Illumina sequencing system), which partially match the adaptor sequences on the 3′ portion (see Fig. S1A). Unless both oligonucleotides of the pair hybridize to a single-stranded template adjacent to each other, ligation will not take place, and they cannot be amplified in the PCR. After PCR amplification, the amplified products from all the experiments were combined for sequencing using the Illumina Nextseq500 platform for a single read of 75 cycles (see Fig. S1C). The sequencing reads were sorted, aligned, and counted at each location for further analysis (see Fig. S1C).

Different combinations of the oligonucleotides and experimental conditions were used in a set of 32 experiments for each mtDNA sample (see Table S4). Six pairs of oligonucleotides in equal molar amounts were pooled to generate eight oligonucleotide pools: four pools were complementary to the L strand (“T”) and four pools were complementary to the H strand (“B”), as listed in Table S4A. Various oligonucleotide pools were included in different experimental tubes at 10-fold excess (for each oligonucleotide) of the mtDNA for the hybridization step of the experiment, with or without denaturation (95°C for 5 min) prior to the hybridization (see Table S4B). After overnight hybridization at 37°C in 10 mM Tris (pH 8) and 50 mM NaCl, ligation was carried out by adding 4 volumes of a ligation mixture to each tube and incubation at room temperature for 30 min (final concentration, 66 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 1.4 mM ATP, and 0.08 units of T4 DNA ligase [Roche]). After ligation, 32 PCR experiments were set up using templates from different combinations of ligated product for each mtDNA sample (see Table S4C). Each PCR experiment was indexed with a unique i7 index primer and each set of 32 experiments from the same mtDNA sample was indexed with a common i5 index primer in the amplification. Each set of 32 experiments for an mtDNA sample with specified treatment was indexed with a unique i5 index primer. Ten denaturing experiments (experiments 17 through 24, 31, and 32) were controls for oligonucleotide hybridization efficiency. Eight experiments (experiments 1 through 8) consisted of one oligonucleotide pool hybridizing to one of the DNA strands with denaturation and three oligonucleotide pools hybridizing to the other DNA strand without denaturation prior to the hybridization step. Eight other experiments (experiments 9 through 16) consisted of all four oligonucleotide pools for the same DNA strand with a single oligonucleotide pool with denaturation and three other oligonucleotide pools without denaturation prior to the hybridization step. The denatured oligonucleotide pool within each of the 16 experiments served as an internal standard (for example, T6-1D for experiment 1, T6-2D for experiment 2, and T6-3D for experiment 3) to calculate the fraction of mtDNA molecules that had single strandedness at each of the 16 oligonucleotide hybridization sites without denaturation. Two experiments (experiments 29 and 30) included four oligonucleotide pools complementary to the same mtDNA strand, and four other experiments (experiments 25 through 28) included two oligonucleotide pools complementary to the L strand and two oligonucleotide pools complementary to the H strand of the mtDNA. These six experiments were done without denaturation prior to the hybridization step, and this allowed the assessment of the relative ratios of single strandedness at the oligonucleotide hybridization sites within each experiment.

Analysis of strand-specific oligonucleotide ligation assay.

The sequencing reads from each sample (more than 16 million reads for each sample treatment) were sorted based on the i5 index, and the reads for each experiment of the same DNA sample were further sorted by the i7 indexes. The sorted reads in each experiment were aligned with the 44 bases of mtDNA sequence (contiguous sequence of each oligonucleotide pair) for each of the 24 locations. The read counts after alignment for each of the 24 locations in each experiment (more than 400,000 reads for each experiment) were compiled and analyzed. The relative hybridization efficiency of each oligonucleotide pair was obtained from each of the 10 denaturing experiments (experiments 17 through 24, 31, and 32). The relative hybridization efficiency for each oligonucleotide pair was derived by dividing the read count at each location by the lowest read count of the 24 locations in the experiment. The read count at each location in other experiments in the set was first normalized by the relative hybridization efficiency derived from the corresponding denaturing experiment that included the same oligonucleotide pools (for example, read counts in experiment 1 were normalized to the relative hybridization efficiency calculated for each site from experiment 17) before further calculation as described below. A relative ratio of hybridization, which reflected the ratio of mtDNA with single strandedness, at each of the 24 locations examined was then calculated. In experiments without a denaturing step, the relative ratio of hybridization was derived by dividing the read count at each location by the lowest read count of the 24 locations in the experiment. In experiments with a mixture of native and denaturing conditions, the relative ratio of hybridization was derived by dividing the read count at each location of the native condition by the average read counts of the six locations of the denaturing condition. The six relative ratios of hybridization for each location from eight experiments were averaged to derive the relative ratio of hybridization of the sample with specified treatment, and the standard deviation was calculated accordingly.

The hybridization efficiency calculated from each sample (experiments 31 and 32) was also used to validate the consistency across the samples. The relative ratios of hybridization calculated from the experiments without the denaturing step from each sample (experiments 25 through 30) were used as controls to compare both within the experiments on the same samples with mixing of denaturing and native conditions and across the samples to ensure that the mixing of different pools of oligonucleotides was within the normal pipetting variation. After extensive testing and many pilot experiments to validate the assay, a total of 576 experiments were carried out for this study.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I thank David VanDenBerg for advice on the oligonucleotide ligation assay, Cindy Okitsu for technical assistance in pilot experiments, and Shuangchao Ma for sorting the sequencing reads from the oligonucleotide ligation assays. I also thank Michael R. Lieber, Ray Mosteller, Nick R. Pannunzio, Di Lu, and Ebi Zandi for critical reading of the manuscript. Susan Groshen from the Biostatistics Core provided helpful discussion on data analysis, and the Molecular Genomics Core sequenced the PCR products from oligonucleotide ligation assays in the study.

The Biostatistics Core and the Molecular Genomics Core are shared resources supported by NCI, of Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center at USC. My greatest appreciation goes to J. Aresty and K. Aresty for funding this study.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at https://doi.org/10.1128/MCB.00406-18.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailey LJ, Doherty AJ. 2017. Mitochondrial DNA replication: a PrimPol perspective. Biochem Soc Trans 45:513–529. doi: 10.1042/BST20160162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ciesielski GL, Oliveira MT, Kaguni LS. 2016. Animal mitochondrial DNA replication. Enzymes 39:255–292. doi: 10.1016/bs.enz.2016.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernández-Silva P, Enriquez JA, Montoya J. 2003. Replication and transcription of mammalian mitochondrial DNA. Exp Physiol 88:41–56. doi: 10.1113/eph8802514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gustafsson CM, Falkenberg M, Larsson NG. 2016. Maintenance and expression of mammalian mitochondrial DNA. Annu Rev Biochem 85:133–160. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060815-014402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holt IJ, Reyes A. 2012. Human mitochondrial DNA replication. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 4:a012971. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a012971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasamatsu H, Vinograd J. 1974. Replication of circular DNA in eukaryotic cells. Annu Rev Biochem 43:695–719. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.43.070174.003403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kasiviswanathan R, Collins TT, Copeland WC. 2012. The interface of transcription and DNA replication in the mitochondria. Biochim Biophys Acta 1819:970–978. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2011.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hayatsu H. 2008. Discovery of bisulfite-mediated cytosine conversion to uracil, the key reaction for DNA methylation analysis—a personal account. Proc Jpn Acad Ser B 84:321–330. doi: 10.2183/pjab.84.321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang FT, Yu K, Balter BB, Selsing E, Oruc Z, Khamlichi AA, Hsieh CL, Lieber MR. 2007. Sequence dependence of chromosomal R-loops at the immunoglobulin heavy-chain Smu class switch region. Mol Cell Biol 27:5921–5932. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00702-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yu K, Chedin F, Hsieh C-L, Wilson TE, Lieber MR. 2003. R-loops at immunoglobulin class switch regions in the chromosomes of stimulated B cells. Nat Immunol 4:442–451. doi: 10.1038/ni919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yu K, Roy D, Huang FT, Lieber MR. 2006. Detection and structural analysis of R-loops. Methods Enzymol 409:316–329. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(05)09018-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zharikov S, Shiva S. 2013. Platelet mitochondrial function: from regulation of thrombosis to biomarker of disease. Biochem Soc Trans 41:118–123. doi: 10.1042/BST20120327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis AF, Clayton DA. 1996. In situ localization of mitochondrial DNA replication in intact mammalian cells. J Cell Physiol 135:883–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Magnusson J, Orth M, Lestienne P, Taanman JW. 2003. Replication of mitochondrial DNA occurs throughout the mitochondria of cultured human cells. Exp Cell Res 289:133–142. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4827(03)00249-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soslau G. 1983. De novo synthesis of DNA in human platelets. Arch Biochem Biophys 226:252–256. doi: 10.1016/0003-9861(83)90291-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nicholls TJ, Minczuk M. 2014. In D-loop: 40 years of mitochondrial 7S DNA. Exp Gerontol 56:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2014.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bogenhagen D, Clayton DA. 1978. Mechanism of mitochondrial DNA replication in mouse L-cells: kinetics of synthesis and turnover of the initiation sequence. J Mol Biol 119:49–68. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(78)90269-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gensler S, Weber K, Schmitt WE, Pérez-Martos A, Enriquez JA, Montoya J, Wiesner RJ. 2001. Mechanism of mammalian mitochondrial DNA replication: import of mitochondrial transcription factor A into isolated mitochondria stimulates 7S DNA synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res 29:3657–3663. doi: 10.1093/nar/29.17.3657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robberson DL, Clayton DA. 1973. Pulse-labeled components in the replication of mitochondrial deoxyribonucleic acid. J Biol Chem 248:4512–4514. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rajala N, Gerhold JM, Martinsson P, Klymov A, Spelbrink JN. 2014. Replication factors transiently associate with mtDNA at the mitochondrial inner membrane to facilitate replication. Nucleic Acids Res 42:952–967. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fusté JM, Shi Y, Wanrooij S, Zhu X, Jemt E, Persson Ö, Sabouri N, Gustafsson CM, Falkenberg M. 2014. In vivo occupancy of mitochondrial single-stranded DNA binding protein supports the strand displacement mode of DNA replication. PLoS Genet 10:e1004832. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kasamatsu H, Robberson DL, Vinograd J. 1971. A novel closed-circular mitochondrial DNA with properties of a replicating intermediate. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 68:2252–2257. doi: 10.1073/pnas.68.9.2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Robberson DL, Kasamatsu H, Vinograd J. 1972. Replication of mitochondrial DNA. Circular replicative intermediates in mouse L cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 69:737–741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.69.3.737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kolesar JE, Wang CY, Taguchi YV, Chou SH, Kaufman BA. 2013. Two-dimensional intact mitochondrial DNA agarose electrophoresis reveals the structural complexity of the mammalian mitochondrial genome. Nucleic Acids Res 41:e58. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks1324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pohjoismäki JL, Holmes JB, Wood SR, Yang MY, Yasukawa T, Reyes A, Bailey LJ, Cluett TJ, Goffart S, Willcox S, Rigby RE, Jackson AP, Spelbrink JN, Griffith JD, Crouch RJ, Jacobs HT, Holt IJ. 2010. Mammalian mitochondrial DNA replication intermediates are essentially duplex but contain extensive tracts of RNA/DNA hybrid. J Mol Biol 397:1144–1155. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2010.02.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yang MY, Bowmaker M, Reyes A, Vergani L, Angeli P, Gringeri E, Jacobs HT, Holt IJ. 2002. Biased incorporation of ribonucleotides on the mitochondrial L-strand accounts for apparent strand-asymmetric DNA replication. Cell 111:95–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yasukawa T, Reyes A, Cluett TJ, Yang MY, Bowmaker M, Jacobs HT, Holt IJ. 2006. Replication of vertebrate mitochondrial DNA entails transient ribonucleotide incorporation throughout the lagging strand. EMBO J 25:5358–5371. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsieh C-L. 1994. The dependence of transcriptional repression on CpG methylation density. Mol Cell Biol 14:5487–5494. doi: 10.1128/MCB.14.8.5487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hirt B. 1967. Selective extraction of polyoma DNA from infected mouse cultures. J Mol Biol 26:365–369. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(67)90307-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.