Abstract

Rationale: Nontuberculous mycobacterial (NTM) pulmonary disease prevalence is increasing.

Objectives: To determine the association between the use of inhaled corticosteroids and the likelihood of NTM pulmonary infection among individuals with treated airway disease.

Methods: We conducted a case–control study of subjects with airway disease with and without NTM pulmonary infection (based on mycobacterial respiratory cultures) between 2000 and 2010 in northern California. We quantified the use of inhaled corticosteroids, other airway disease medications, and healthcare use within 6 months of NTM pulmonary infection identification. We used 1:10 case–control matching and conditional logistic regression to evaluate the association between the duration and cumulative dosage of inhaled corticosteroid use and NTM pulmonary infection.

Results: We identified 248 cases with NTM pulmonary infection with an estimated rate of 16.4 cases per 10,000 subjects treated for airway disease. The median interval between treated airway disease cohort entry (defined as date of patient filling the third airway disease treatment prescription) and NTM case identification was 1,217 days. Compared with control subjects, subjects with NTM pulmonary infection were more likely to use airway disease medications including systemic steroids; they were also more likely to use health care. Any inhaled corticosteroids use between 120 days and 2 years before cohort entry was associated with substantially increased odds of NTM infection. For example, the adjusted odds ratio for NTM infection among inhaled corticosteroid users in a 2-year interval was 2.51 (95% confidence interval, 1.40–4.49; P < 0.01). Increasing cumulative inhaled corticosteroid dose was also associated with greater odds of NTM infection.

Conclusions: Inhaled corticosteroid use, and particularly high-dose inhaled corticosteroid use, was associated with an increased risk of NTM pulmonary infection.

Keywords: nontuberculous mycobacteria, bronchiectasis, inhaled corticosteroid, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, infection

Nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) are environmental organisms that can cause progressive lung disease associated with high morbidity and mortality (1). Recent epidemiologic studies have reported that the incidence of NTM pulmonary disease is rising globally (2–5). Although precise estimates have been limited by heterogeneity in case definitions and variability in diagnostic reporting, population-based assessments estimate the annual prevalence of NTM pulmonary disease to be as high as 47 cases per 100,000 patients in selected North American surveys (6, 7), with the highest prevalence rates observed in older patients (2, 8).

The clinical impact of NTM pulmonary infection can be substantial owing to relatively poor response rates to current multidrug therapy (1) and the almost universal airway injury and resulting bronchiectasis that accompany NTM pulmonary disease. The resulting chronic and progressive disease can cause significant morbidity and mortality (4, 9, 10) and can impair quality of life (11). The impact of NTM infections on healthcare systems is also substantial, with disproportionate costs resulting from the need for chronic and complex treatment regimens (12–14).

The factors predisposing patients to the acquisition of NTM pulmonary disease, or the rising prevalence of the disease, remain poorly understood (8, 14). Aspects of exposure environment, intrinsic host response and infection susceptibility, and acquired susceptibility modifiers have been considered as potentially important factors in the increased prevalence. In addition, recent studies suggest that the use of inhaled corticosteroids (ICS)—an increasingly common therapy for patients with common airway diseases, including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), and bronchiectasis—is associated with an increased risk of NTM pulmonary disease (5, 9, 15, 16). Corticosteroids can attenuate cellular immunity against intracellular pathogens, including mycobacteria, raising the potential that ICS could alter airway immune responses and predispose patients to NTM infection and disease persistence (17). This potential effect would most likely manifest itself in individuals with chronic airway disease including bronchiectasis, in part owing to the increasing use of chronic ICS therapy in this clinical population, even in the absence of data supporting any benefit of this drug class in bronchiectasis (18–20).

The potential adverse effect of ICS to increase the risk of NTM disease in patients with COPD has been explored in two recent studies in different populations. Andréjak and colleagues found in a nationwide Danish registry that ICS use was associated with increased odds of NTM disease in patients with chronic respiratory disease (20). In a case–control study in Ontario, Canada, examining individuals older than 65 years of age with chronic airway disease, Brode and colleagues found that ICS use was associated with an increased risk of NTM pulmonary disease (5).

With emerging support for the hypothesis that ICS use can increase the risk of NTM disease in patients with chronic airway disease, we sought to determine whether this potential causative association could be confirmed in a separate and large patient population. Accordingly, in a large and diverse patient population, we investigated the hypothesis that ICS use increases the risk for pulmonary NTM infection in patients with treated chronic airway disease.

Methods

The population for this case–control study was identified from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California integrated healthcare delivery system, which includes 4.1 million persons representing the diverse demographics of a broad geographical region (21 hospitals, 242 medical offices). The Kaiser Permanente system uses a single electronic medical record system for clinical and laboratory data for its entire healthcare system, thus providing access to a robust database for clinical investigation. This study was approved by the Kaiser Permanente Northern California Institutional Review Board.

Identifying Patients with Airway Disease

Figure 1 displays our treated airway disease cohort identification and case–control matching approach. To identify subjects with airway disease, we screened for provider-reported International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM), diagnosis codes among adults (aged ≥18 yr) enrolled in the Kaiser Permanente Northern California integrated healthcare delivery system between January 1, 2000, and December 31, 2010. The use of this database provided access to a large and very broad community-based subject cohort to avoid biases potentially inherent in smaller or preselected subject cohorts. We identified subjects (n = 636,327) with at least one healthcare provider–reported inpatient or outpatient ICD-9 code for asthma (493), COPD (491 or 492), and bronchiectasis (494). Given the substantial variability in accuracy of diagnosis of these chronic respiratory diseases, as well as the significant variability in the assignment of ICD disease codes in bronchiectasis populations (21), we included all these ICD diagnosis codes in our search. From the total identified study population, we specifically excluded subjects (n = 8,427) with any ICD-9 diagnosis code of tuberculosis (010–018) or cystic fibrosis (277).

Figure 1.

Cohort identification and case–control matching for primary analysis. AFB = acid-fast bacilli; COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; NTM = nontuberculous mycobacterial.

Treated Cohort of Patients with Airway Disease

To further identify a treated cohort of patients with airway disease, we evaluated outpatient pharmacy records to select subjects (n = 279,333) who filled at least three prescriptions for airway disease medications within a 1-year period surrounding their first assignment of an ICD-9 airway disease diagnosis code. Airway disease medications were broadly categorized as follows: isolated ICS (beclomethasone, budesonide, flunisolide, fluticasone, mometasone, or triamcinolone); mixed ICS, also termed ICS with long-acting β-agonist (ICS/LABA); and non-ICS medications, consisting of short-acting β-agonists (albuterol or levalbuterol), LABAs (salmeterol or formoterol), anticholinergics (ipratropium or tiotropium), antileukotriene medications (montelukast, zafirlukast, or zileuton), or others (cromolyn or theophylline). In the cohort treated for airway disease, we defined the “cohort entry” date for determination of treatment duration as the date on which the third prescription was filled. This cohort was then used to identify NTM infection cases and control subjects.

Identifying NTM Infection Cases

From among the treated airway disease cohort, we identified subjects with NTM pulmonary infection (n = 549) based on respiratory acid-fast bacilli (AFB) cultures to maximize specificity. We defined confirmed NTM infection cases as either 1) subjects with any single AFB culture positive for NTM species from a bronchoscopic specimen or 2) subjects with at least two positive AFB cultures for NTM from a sputum source within a 1-year period. For subjects identified by two positive sputum cultures, the NTM “case index” date was set to the date at which the first positive result was reported, and the NTM species was based on the first positive result. We then defined the NTM case duration interval as the number of days between a subject’s NTM case index date and their treated airway disease cohort entry date, including subjects only when their NTM case identification date occurred after their airway disease cohort entry date (n = 310). We excluded subjects with an NTM diagnosis code preceding their case identification index date (n = 6).

Case–Control Matching

For each of the confirmed NTM cases in our primary analysis, we randomly selected 10 control subjects from the treated airway disease cohort; we excluded individuals with NTM cultures positive only for Mycobacterium gordonae because of the very low likelihood of pathogenicity of this organism. Control subjects were matched by age (in 5-yr increments), sex, and airway disease at the cohort entry date (hierarchically categorized as bronchiectasis, COPD, and asthma). For each control subject, we censored their clinical data by the number of days from airway disease cohort entry to replicate their matched case’s NTM case duration interval; no matched control subjects had diagnosis codes for NTM pulmonary disease after the censoring date. We determined the presence of subject comorbidities on the basis of ICD-9 codes before cohort entry dates (i.e., diabetes, gastroesophageal reflux disease, interstitial lung disease, rheumatoid arthritis) as well as the use of other medication based on pharmacy records (i.e., anti–tumor necrosis factor-α antagonists, oral corticosteroids, other immunosuppressants, and proton pump inhibitors).

Quantifying ICS Use

For cases and matched control subjects, we calculated the daily dose of ICS medication over a 1-year look-back period from the case index date. We used a standardized ICS beclomethasone equivalency chart to characterize the dosage of each prescription as high, medium, or low (22). For prescription periods that overlapped, we counted only a single medication dose, preferentially taking the most recent prescription. We then quantified the number of days in the look-back period during which an ICS was prescribed, as well as the cumulative dosage of high-, medium-, and low-dose ICS use. We used the same procedure to capture the percentage of days using other airway medications as well as systemic corticosteroids (prednisone, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, and dexamethasone). We considered ICS/LABA medications as contributing to the ICS category. Over the same look-back period, we determined the percentage of days patients spent in outpatient visits, emergency department visits, and hospitalizations.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics are displayed using mean ± standard deviation or median (interquartile range). Comparisons between groups are based on t tests, Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, or chi-square tests. We used conditional logistic regression to evaluate the association between the duration of ICS use and NTM pulmonary infection in unadjusted and adjusted analyses. We adjusted for concomitant use of non-ICS medications in the medication-adjusted model and added demographic, comorbidity, and use variables in the fully adjusted model. To evaluate a potential dose–response relationship between ICS use and NTM pulmonary infection, we categorized 1-year ICS use in low–, medium–, and high–cumulative dose categories. In sensitivity analyses, we also evaluated look-back periods of 120 days and 2 years before cohort entry. We used Stata/SE 13.1 software (StataCorp) to conduct statistical analyses.

Results

Between 2000 and 2010, we identified a total of 549 subjects with NTM infection on the basis of two or more positive AFB sputum sample cultures and/or one positive AFB bronchoscopic sample culture. Mycobacterium avium-intracellulare was the NTM pathogen identified in 368 (67.0%) (Table 1) of positive samples, followed by M. gordonae (n = 91 [16.6%]), M. abscessus (n = 29 [5.3%]), and M. fortuitum (n = 25 [4.6%]). Excluding M. gordonae occurrences, this represented 16.4 NTM infection cases per 10,000 subjects treated for airway disease.

Table 1.

Nontuberculous mycobacteria identified in respiratory sample mycobacterial cultures from all treated patients with airway disease

| Mycobacterial Species | n (% of Total) |

|---|---|

| M. avium-intracellulare | 368 (67.0) |

| M. gordonae | 91 (16.6) |

| M. abscessus | 29 (5.3) |

| M. fortuitum | 25 (4.6) |

| M. chelonae | 19 (3.5) |

| M. kansasii | 19 (3.5) |

| M. szulgai | 6 (1.1) |

| M. xenopi | 4 (0.7) |

| M. simiae-avium | 4 (0.7) |

| M. terrae | 3 (0.6) |

| M. lentiflavum | 2 (0.4) |

| M. scrofulaceum | 2 (0.4) |

| M. aurum | 1 (0.2) |

| M. mucogenicum | 1 (0.2) |

| M. flavescens | 1 (0.2) |

| M. asiaticum | 1 (0.2) |

| M. interjectum | 1 (0.2) |

| M. gastri | 1 (0.2) |

Definition of abbreviation: M. = Mycobacterium.

Note: M. gordonae isolates were excluded as a possible cause of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infection.

NTM Case–Control Matching

After restricting the cohort sample to individuals who were treated for airway disease before their AFB case positivity, our analytic cohort included 248 non–M. gordonae NTM infection cases with a cohort duration of at least 6 months. Median duration of follow-up between treated airway disease cohort entry and AFB case identification was 1,217 days (interquartile range, 525–2,139 d). The mean age of the sample was 64.2 ± 13.0 years, and 63.3% of cases were female (Table 2). The greatest number of subjects had a clinical provider–assigned diagnosis of asthma (by ICD code) at cohort entry (n = 148 [59.7%]), whereas 73 (29.4%) had a provider-assigned ICD diagnosis of COPD. In addition, 30.6% (n = 76) of cases had multiple diagnoses, in particular patients with concomitant diagnoses of asthma and COPD.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infection cases and matched control subjects

| NTM Cases | Control Subjects | |

|---|---|---|

| No. | 248 | 2,480 |

| Age, yr | 64.1 ± 13.1 | 64.2 ± 13.1 |

| Female sex | 157 (63.3%) | 1,570 (63.3) |

| Entry diagnosis | ||

| Asthma | 148 (59.7) | 1,480 (59.7) |

| Bronchiectasis | 27 (10.9) | 270 (10.9) |

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 73 (29.4) | 730 (29.4) |

| Race | ||

| White | 180 (72.9) | 1,727 (70.1) |

| Comorbid diagnoses | ||

| Diabetes mellitus | 26 (10.5) | 359 (14.5) |

| Gastroesophageal disease | 32 (12.9) | 350 (14.1) |

| Interstitial lung disease | 14 (5.7) | 86 (3.5) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 10 (4.0) | 31 (1.3) |

| Healthcare use in past year | ||

| Ambulatory visit | 246 (99.2) | 2,320 (93.6) |

| Emergency department | 95 (38.3) | 616 (24.8) |

| Hospitalization | 113 (45.6) | 661 (26.7) |

| Airway disease medication use in past 120 d | ||

| ICS | 187 (75.4) | 1,111 (44.8) |

| Mixed ICS + LABA | 42 (16.9) | 161 (6.5) |

| SABA | 108 (43.6) | 725 (29.2) |

| LABA | 39 (15.7) | 201 (8.1) |

| Anticholinergic | 104 (41.9) | 437 (17.6) |

| Leukotriene antagonist | 29 (11.3) | 96 (3.9) |

| Oral corticosteroid | 90 (36.3) | 353 (14.2) |

| Other drug exposure in past year | ||

| TNF-α antagonist | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.1) |

| Other immunosuppressant | 11 (4.4) | 54 (2.2) |

| Proton pump inhibitor | 48 (19.4) | 414 (16.7) |

Definition of abbreviations: ICS = inhaled corticosteroid; LABA = long-acting β-agonist; NTM = nontuberculous mycobacteria; SABA = short-acting β-agonist; TNF-α = tumor necrosis factor-α.

Data are mean ± standard deviation and frequency (percent).

Medication and Healthcare Use Patterns

Compared with control subjects, patients with NTM infection were more likely to have used ICS before cohort entry (Table 2). NTM infection cases were also more likely than control subjects to have used most other medications, including systemic corticosteroids (36.3% vs. 14.2%). NTM cases also demonstrated more frequent healthcare use based on ambulatory, emergency department, and hospital visits.

Association between ICS Treatment and NTM Infection Cases

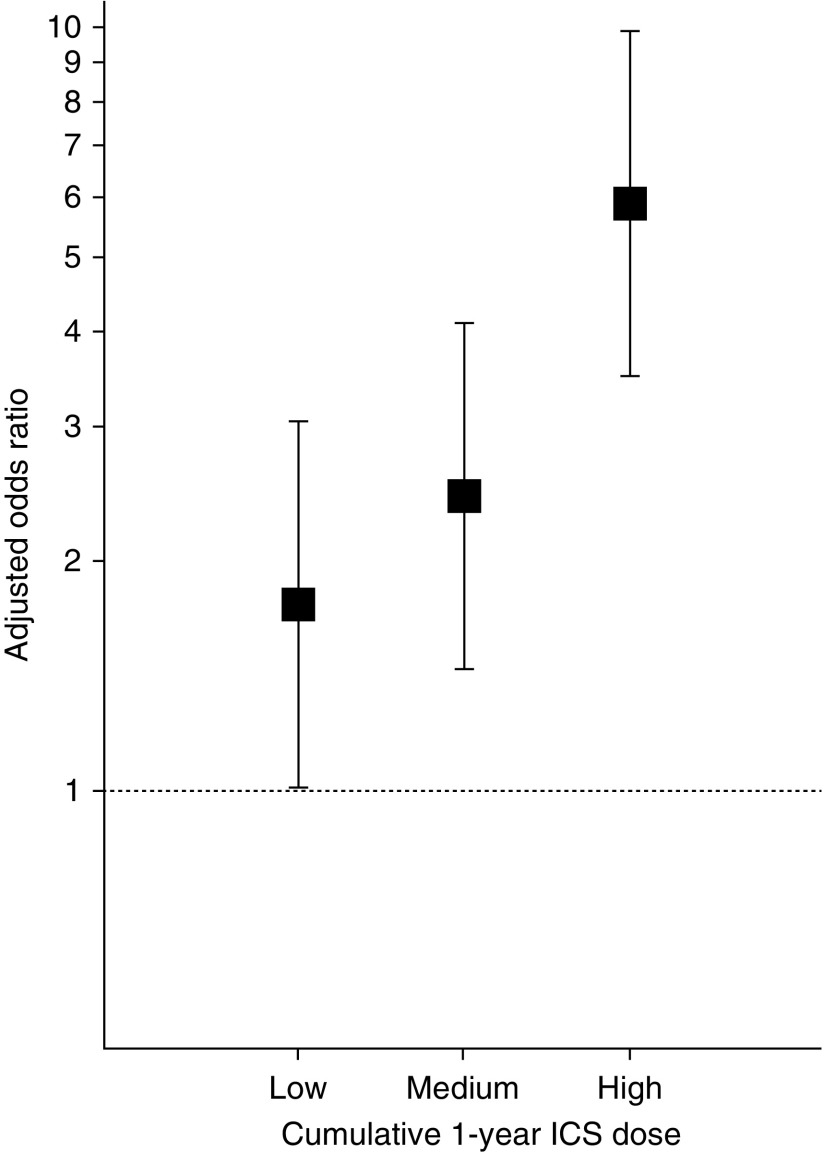

Any ICS use within the 1 year before cohort entry was associated with substantially increased odds of NTM infection (Table 3) (adjusted odds ratio, 2.80; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.79–4.37; P < 0.01). A similar association was present for any ICS use in the 120 days (odds ratio, 2.74; 95% CI, 1.83–4.09; P < 0.01) or 2 years (odds ratio, 2.51; 95% CI, 1.40–4.49; P < 0.01) before cohort entry. Increasing cumulative ICS dosage in the year before cohort entry (based on tertiles of beclomethasone-equivalent ICS dose) was associated with increasing odds of NTM infection (Figure 2).

Table 3.

Association of inhaled corticosteroid use with risk of nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infection, stratified by period of inhaled corticosteroid use before cohort entry and diagnosis at cohort entry

| Any ICS use | n | Odds Ratios (95% Confidence Interval) for NTM Infection with ICS Use |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted OR | Medication-adjusted OR* | Fully Adjusted OR† | ||

| Within prior 120 d | 2,728 | 3.88 (2.87–5.26) | 2.86 (2.02–4.05) | 2.74 (1.83–4.09) |

| Within past 1 yr | 2,321 | 4.14 (2.80–6.13) | 3.04 (1.97–4.68) | 2.80 (1.79–4.37) |

| Within past 2 yr | 1,829 | 4.49 (2.62–7.70) | 2.82 (1.59–5.00) | 2.51 (1.40–4.49) |

Definition of abbreviations: ICS = inhaled corticosteroid; NTM = nontuberculous mycobacteria; OR = odds ratio.

The medication-adjusted model adjusts for prior use of airway treatment medications, oral corticosteroids, immunosuppressant medications, and proton pump inhibitors over the same period.

The fully adjusted model includes medications as well as age, sex, entry diagnosis, comorbid conditions (diabetes, gastroesophageal reflux disease, interstitial lung disease, rheumatoid arthritis), and healthcare use over the same period.

Figure 2.

Adjusted odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for nontuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary infection based on tertiles of cumulative dosage of beclomethasone-equivalent inhaled corticosteroid (ICS) use in the 1 year before cohort entry. The reference group is patients without ICS use in the year before cohort entry.

Discussion

In this study, we drew from a large and diverse population-based sample of northern California subjects with treated chronic airway disease to evaluate the association between ICS use and NTM pulmonary infection. We found that NTM infection was associated with preceding ICS use and that there was evidence for a dose–response relationship. Each month of high-dose ICS use was independently associated with greatly increased odds of developing NTM pulmonary infection, even after adjusting for other airway disease treatments and healthcare use metrics. These data represent an important finding regarding potential factors contributing to the increasing prevalence of respiratory NTM infection and may link the use of ICS with the increasing prevalence.

Although the relative absence of standardized public reporting requirements for NTM infections may limit the overall applicability of some data, available infection surveillance data reveal a significant and continued increase in NTM infection prevalence over the last three decades. The prevalence of pulmonary NTM infections in the early 1980s was reported to be as high as 1.8 cases per 100,000 persons, further increasing to 3–4 cases per 100,000 persons in the 1990s (23). Prevalence has continued to increase, with recent studies revealing regional prevalence of over 40 per 100,000 (24). In our study, we noted a substantially higher incidence rate among patients with treated airway disease than in the general population.

The causes of increasing NTM disease prevalence are uncertain, but a potentially important factor is the contribution of corticosteroid therapy, and in particular ICS therapy, to NTM disease pathogenesis. Over the same period of an observed marked increase in NTM infection prevalence, the use of ICS has also increased dramatically. First introduced in Europe in the 1970s, and then in North America in the early 1980s, ICS use has continued to grow substantially, initially with greater penetrance of use in asthma populations but importantly now with broad use in patients with COPD (18, 19). Although it remains uncertain whether the current use of ICS in COPD populations is justified by available data (25, 26), ICS use in COPD is very common. Prescription data from North America and Europe reveal ICS use in 40–75% of patients with COPD (27, 28), and the penetrance of ICS use in COPD appears to be increasing (29–31). Also, importantly, although no data exist to support any benefit of ICS deriving to patients with bronchiectasis, the use of ICS in this population is substantial. The recent published data from a national registry study of patients with bronchiectasis revealed that over 50% of that bronchiectasis cohort were treated with ICS, even though only a small minority had either an asthma or COPD diagnosis to potentially support the use of ICS in a treatment regimen (21).

Corticosteroids can alter cellular immune function, critically important in host response and defense against pathogens, and this may contribute substantially to risk of pulmonary infections, including NTM infection. Human histopathological data in patients with COPD have demonstrated substantial increased adaptive immune responses in infected peripheral airways (32), and these airway immune responses appear to be significantly attenuated by ICS, even when airway remodeling and mucus impaction are not reduced by ICS (33). In addition, animal data reveal significant suppression by ICS of multiple cytokine mediators of host responses to intracellular pathogens (34). Thus, ICS may produce an airway environment that is permissive for infections. This indeed appears to be the case on the basis of available background clinical data derived from studying ICS use in COPD. In addition, and supporting the concerns for adverse effects of ICS on the risk for NTM disease, a recent study of the immune genetic phenotypic responses in patients with NTM disease provides direct study corroboration for the central involvement of adaptive cellular immune responses involving the interferon-γ–mediated pathway, an immune response component that is also substantially affected by exogenous corticosteroids (35).

Prior and substantial studies suggest that the use of ICS therapy in COPD populations is associated with an increased risk for pulmonary infections (36, 37). Similarly, ICS use has been associated with increased risks of tuberculosis infection (38, 39). Brassard and colleagues reported that in a large population-based sample of patients without oral steroid use, high-dose ICS use was associated with a roughly twofold increase in the risk of pulmonary tuberculosis infection.

Prior studies have also suggested that ICS use is associated with increases in NTM pulmonary infection (4, 5, 9, 15, 20). Hojo and colleagues evaluated a cohort of 464 patients with asthma in Japan, 14 of whom were found to have NTM infections, and they found that patients with NTM infections were more likely to have used fluticasone at higher doses than those used in patients with asthma who did not have NTM disease (15). In a larger study examining 332 patients with pulmonary NTM disease and 3,320 general population matched control subjects in Denmark, Andréjak and colleagues found that the presence of chronic respiratory disease was associated with an increased likelihood of NTM disease, but they also discovered that there was a significantly increased odds of NTM disease among patients with respiratory disease who also were exposed to ICS (9). In addition, in a recent large, population-based, nested case–control study in Ontario, Canada, researchers reported an increased risk of NTM pulmonary disease in an older cohort (age >65 yr), offering added support to the hypothesis that chronic treatment with ICS is associated with a dose-dependent increased risk of NTM disease (5).

Our analysis of a large patient population reveals a significant association between ICS use in patients with chronic airway diseases and an increased risk of NTM infection, and it complements and extends the findings of these previously report studies. Indeed, a comparative analysis of our study and the recent report by Brode and colleagues (5) reveals substantial concordance of the central data of our study and their report. In their similarly structured, population-based, nested case–control study (although restricted to only subjects over age 65 yr), Brode and colleagues found an adjusted odds ratio of 1.86 for NTM disease in ICS users compared with nonusers (95% CI, 1.60–2.15). The adjusted odds ratio in our study was 2.74 (95% CI, 1.83–4.09; P < 0.01), and in the report by Andréjak and colleagues (20), a similar positive association was noted for ICS and risk of NTM disease. In addition, Andréjak and colleagues (20) and Brode and colleagues (5) also found, as we did in our present study, a significant dose–response association between increasing cumulative ICS dosage and increasing odds of NTM infection (Figure 2). Importantly, our study extends the observations and conclusions of Brode and colleagues to include subjects under as well as over age 65, thus avoiding that limitation in their study, while fully supporting the conclusions regarding infection risk from their study as well as that of Andréjak and colleagues.

The known cellular immune-modulatory effects of ICS support a possible causal link between ICS and NTM infection risk, and our data are concordant with other reports of ICS association with infection risk in COPD. The magnitude of the effect revealed in this analysis and the very substantial clinical consequences of NTM pulmonary infection raise the important question whether the broad and increasing use of ICS for COPD needs to be reconsidered.

There are important limitations of our study. First, although we used the American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America consensus microbiological criteria to identify patients with NTM infection, we have not ascertained whether these subjects also met the consensus definition of NTM pulmonary disease. Our case ascertainment method is comparable to that used by Brode and colleagues (5). Although we have not investigated the relationship between these microbiologically defined cases and consensus definition of NTM pulmonary disease in this population, prior published work has established that 1) the use of American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America consensus microbiological disease criteria are valid as a surveillance tool for identifying pulmonary NTM disease, with a roughly 85% concordance of microbiological disease definition with clinical disease definition (38); and 2) the prognosis of individuals meeting consensus microbiological NTM infection criteria is highly concordant with the prognosis of individuals meeting consensus NTM clinical disease definition (4).

Second, although we followed a rigorous matching protocol, we found notable baseline differences between our cases and control subjects in medication and healthcare use; these differences were also present when we matched by medication and systemic steroid use at cohort entry. Although we adjusted for these use differences in our regression model, we cannot eliminate the potential contribution of residual confounding. This includes the possibility of protopathic bias (i.e., symptom-based treatment in the absence of clear clinical knowledge of the underlying disease[s]), and this potential for protopathic bias could extend to include ICS exposure. Third, although there may be differences in immune system modulation by various ICS, and thus drug-related differences in NTM infection risk dependent on specific ICS used, we have not analyzed these data to answer that question. We have, however, made dose equivalence adjustments using broadly accepted standard ICS equivalence adjustments, and thus we doubt that differences in specific ICS used by patients included in this study account for the results we report. Fourth, we chose the case–control study design because of the relatively rare occurrence of NTM pulmonary infection even in our large starting population. However, the case–control approach did not allow us to establish a causal link between ICS use and NTM pulmonary infection. Additional studies, using more robust study designs, are needed to clarify this link. Finally, our inclusion of a broad range of clinical diagnoses of chronic obstructive diseases as designated by ICD-9 codes should be noted. Given the increasingly broad use of ICS in patients with chronic airway diseases, and given the variability in assignment of disease diagnosis (and thus ICD code) by clinicians, plus the intrinsic biological and pathological overlaps that exist between specific chronic airway diseases, we chose to more broadly include chronic airway disease diagnoses, including COPD and asthma, in addition to bronchiectasis (21, 40–44).

Although the approach taken in our analysis might have included some patients in the exposure group who may have no underlying bronchiectasis, if this were the case, it would have the effect of biasing our analysis to the null hypothesis. Thus, our analytical approach allows for a more robust conclusion in consideration of our underlying hypothesis. In addition, past studies of NTM infection risk have clearly identified and included in their analyses subjects without a bronchiectasis diagnosis. In the reports by both Brode and colleagues and Cowman and colleagues, only a minority of identified NTM disease cases had an established concurrent diagnosis of bronchiectasis (5, 35). Published data do not support an argument that NTM infections occur only in patients with previously identified bronchiectasis, so an a priori restriction of our analysis only to patients with a diagnosis of bronchiectasis would have been clinically unwise and not defensible for a robust investigation of the question.

In summary, in our present study, we found that ICS use was associated with a substantial increased risk of NTM pulmonary infection. In the face of uncertainty regarding possible benefits of ICS in COPD, these data argue for a reanalysis of the broad use of ICS in chronic airway diseases.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by the Bill and Jean Lane Center for Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Disease; by the Department of Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine; and by National Institute of General Medical Science grant K23GM112018 (V.X.L.).

Author Contributions: Study conception and design: V.X.L., K.L.W., and S.J.R.; analysis and interpretation: V.X.L., K.L.W., Y.L., H.S., H.U.N., and S.J.R.; drafting the manuscript for important intellectual content: V.X.L., K.L.W., H.S., and S.J.R.; and guarantor of the manuscript, accepting responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole: S.J.R.

Author disclosures are available with the text of this article at www.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1.McShane PJ, Glassroth J. Pulmonary disease due to nontuberculous mycobacteria: current state and new insights. Chest. 2015;148:1517–1527. doi: 10.1378/chest.15-0458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prevots DR, Shaw PA, Strickland D, Jackson LA, Raebel MA, Blosky MA, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease prevalence at four integrated health care delivery systems. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:970–976. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201002-0310OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cassidy PM, Hedberg K, Saulson A, McNelly E, Winthrop KL. Nontuberculous mycobacterial disease prevalence and risk factors: a changing epidemiology. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;49:e124–e129. doi: 10.1086/648443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winthrop KL, McNelley E, Kendall B, Marshall-Olson A, Morris C, Cassidy M, et al. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease prevalence and clinical features: an emerging public health disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:977–982. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201003-0503OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brode SK, Campitelli MA, Kwong JC, Lu H, Marchand-Austin A, Gershon AS, et al. The risk of mycobacterial infections associated with inhaled corticosteroid use. Eur Respir J. 2017;50:1700037. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00037-2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al Houqani M, Jamieson F, Chedore P, Mehta M, May K, Marras TK. Isolation prevalence of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacteria in Ontario in 2007. Can Respir J. 2011;18:19–24. doi: 10.1155/2011/865831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adjemian J, Olivier KN, Seitz AE, Holland SM, Prevots DR. Prevalence of nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease in U.S. Medicare beneficiaries. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;185:881–886. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201111-2016OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Henkle E, Hedberg K, Schafer S, Novosad S, Winthrop KL. Population-based incidence of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in Oregon 2007 to 2012. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:642–647. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201412-559OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Andréjak C, Thomsen VO, Johansen IS, Riis A, Benfield TL, Duhaut P, et al. Nontuberculous pulmonary mycobacteriosis in Denmark: incidence and prognostic factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181:514–521. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200905-0778OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mirsaeidi M, Machado RF, Garcia JG, Schraufnagel DE. Nontuberculous mycobacterial disease mortality in the United States, 1999-2010: a population-based comparative study. PLoS One. 2014;9:e91879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta M, Marras TK. Impaired health-related quality of life in pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease. Respir Med. 2011;105:1718–1725. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Strollo SE, Adjemian J, Adjemian MK, Prevots DR. The burden of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in the United States. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:1458–1464. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201503-173OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leber A, Marras TK. The cost of medical management of pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease in Ontario, Canada. Eur Respir J. 2011;37:1158–1165. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00055010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomson R, Donnan E, Unwin S. Nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease: time to get a grip! Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12:1425–1427. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.201508-524ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hojo M, Iikura M, Hirano S, Sugiyama H, Kobayashi N, Kudo K. Increased risk of nontuberculous mycobacterial infection in asthmatic patients using long-term inhaled corticosteroid therapy. Respirology. 2012;17:185–190. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2011.02076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dirac MA, Horan KL, Doody DR, Meschke JS, Park DR, Jackson LA, et al. Environment or host? A case–control study of risk factors for Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:684–691. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201205-0825OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marras TK. Host susceptibility or environmental exposure in Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease: it takes two to tango. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2012;186:585–586. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201208-1432ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calverley PM, Anderson JA, Celli B, Ferguson GT, Jenkins C, Jones PW, et al. TORCH investigators. Salmeterol and fluticasone propionate and survival in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:775–789. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wedzicha JA, Calverley PM, Seemungal TA, Hagan G, Ansari Z, Stockley RA INSPIRE Investigators. The prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease exacerbations by salmeterol/fluticasone propionate or tiotropium bromide. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:19–26. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200707-973OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andréjak C, Nielsen R, Thomsen VO, Duhaut P, Sørensen HT, Thomsen RW. Chronic respiratory disease, inhaled corticosteroids and risk of non-tuberculous mycobacteriosis. Thorax. 2013;68:256–262. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-201772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henkle E, Aksamit TR, Barker AF, Curtis JR, Daley CL, Anne Daniels ML, et al. Pharmacotherapy for non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: results from an NTM Info & Research patient survey and the Bronchiectasis and NTM Research Registry. Chest. 2017;152:1120–1127. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.04.167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly HW. Comparison of inhaled corticosteroids: an update. Ann Pharmacother. 2009;43:519–527. doi: 10.1345/aph.1L546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, Gordin F, et al. ATS Mycobacterial Diseases Subcommittee; American Thoracic Society; Infectious Diseases Society of America An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007175367–416.[Published erratum appears in Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:744–745.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marras TK, Mendelson D, Marchand-Austin A, May K, Jamieson FB. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease, Ontario, Canada, 1998-2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1889–1891. doi: 10.3201/eid1911.130737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nannini LJ, Lasserson TJ, Poole P. Combined corticosteroid and long-acting β2-agonist in one inhaler versus long-acting β2-agonists for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(9):CD006829. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006829.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ernst P, Saad N, Suissa S. Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD: the clinical evidence. Eur Respir J. 2015;45:525–537. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00128914. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Niewoehner DE, Erbland ML, Deupree RH, Collins D, Gross NJ, Light RW, et al. Department of Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group. Effect of systemic glucocorticoids on exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1941–1947. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199906243402502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Andel AE, Reisner C, Menjoge SS, Witek TJ. Analysis of inhaled corticosteroid and oral theophylline use among patients with stable COPD from 1987 to 1995. Chest. 1999;115:703–707. doi: 10.1378/chest.115.3.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bourbeau J, Sebaldt RJ, Day A, Bouchard J, Kaplan A, Hernandez P, et al. Practice patterns in the management of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in primary practice: the CAGE study. Can Respir J. 2008;15:13–19. doi: 10.1155/2008/173904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mehuys E, Boussery K, Adriaens E, Van Bortel L, De Bolle L, Van Tongelen I, et al. COPD management in primary care: an observational, community pharmacy-based study. Ann Pharmacother. 2010;44:257–266. doi: 10.1345/aph.1M481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith CJ, Gribbin J, Challen KB, Hubbard RB. The impact of the 2004 NICE guideline and 2003 General Medical Services contract on COPD in primary care in the UK. QJM. 2008;101:145–153. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hogg JC, Chu F, Utokaparch S, Woods R, Elliott WM, Buzatu L, et al. The nature of small-airway obstruction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:2645–2653. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hogg JC, Chu FS, Tan WC, Sin DD, Patel SA, Pare PD, et al. Survival after lung volume reduction in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: insights from small airway pathology. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;176:454–459. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200612-1772OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Patterson CM, Morrison RL, D’Souza A, Teng XS, Happel KI. Inhaled fluticasone propionate impairs pulmonary clearance of Klebsiella pneumoniae in mice. Respir Res. 2012;13:40. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-13-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cowman SA, Jacob J, Hansell DM, Kelleher P, Wilson R, Cookson WOC, et al. Whole-blood gene expression in pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial infection. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2018;58:510–518. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2017-0230OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yawn BP, Li Y, Tian H, Zhang J, Arcona S, Kahler KH. Inhaled corticosteroid use in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and the risk of pneumonia: a retrospective claims data analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2013;8:295–304. doi: 10.2147/COPD.S42366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suissa S, Patenaude V, Lapi F, Ernst P. Inhaled corticosteroids in COPD and the risk of serious pneumonia. Thorax. 2013;68:1029–1036. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-202872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Brassard P, Suissa S, Kezouh A, Ernst P. Inhaled corticosteroids and risk of tuberculosis in patients with respiratory diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:675–678. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201007-1099OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lee CH, Kim K, Hyun MK, Jang EJ, Lee NR, Yim JJ. Use of inhaled corticosteroids and the risk of tuberculosis. Thorax. 2013;68:1105–1113. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2012-203175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gibson PG, Simpson JL. The overlap syndrome of asthma and COPD: what are its features and how important is it? Thorax. 2009;64:728–735. doi: 10.1136/thx.2008.108027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Du Q, Jin J, Liu X, Sun Y. Bronchiectasis as a comorbidity of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0150532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.De la Rosa D, Martínez-Garcia MA, Giron RM, Vendrell M, Olveira C, Borderias L, et al. Clinical impact of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on non-cystic fibrosis bronchiectasis: a study on 1,790 patients from the Spanish Bronchiectasis Historical Registry. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0177931. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0177931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Mao B, Lu HW, Li MH, Fan LC, Yang JW, Miao XY, et al. The existence of bronchiectasis predicts worse prognosis in patients with COPD. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10961. doi: 10.1038/srep10961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Novosad SA, Barker AF. Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and bronchiectasis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2013;19:133–139. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e32835d8312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.